The article title may seem like an outrageous claim, but I’d bet my life on it. Read on to find out more!

I’m going to let you in on a little industry secret that will increase your chances of selling a script one hundred-fold. That is no exaggeration, my friend. Of course, a major concession will have to be made. You will need to write somebody else’s story. Or, at least, the core of the concept will not be yours. But this shouldn’t matter to you. Writing other peoples’ ideas is how the Hollywood screenwriting business operates.

So how does this magical pill work? Well, we all know that Hollywood is an IP-driven business. They want their Twilights, their Avengers, their Lara Crofts, because all of these properties already have a built-in audience. That’s what Hollywood is paying for when it buys a Harry Potter. An audience they know will spend money to watch their films.

But there’s a loophole to this strategy – a way to appeal to audiences just as big, but that will cost the studio nothing more than the price of your script (pennies compared to a deal for The Hunger Games). If you’re a studio head looking for any bargain you can find, that sounds like a deal too good to pass up. So what’s the loophole?

The public domain.

These are properties that have lapsed past the required 92 years in which a property can be owned, and are now available to anyone to write about. There are TONS of great (and popular!) stories that are available to you in the public domain.

And Hollywood loves these properties. Sure, they don’t have the “newness” factor of, say, a Katniss Everdeen. But in a way they have something better. LONGETIVITY. A proven track record that they’ve worked over and over again.

Now when I first started writing, I hated the idea of the public domain. Why would I write some bunk idea from a guy who died 200 years ago? Ahh, but here’s the thing. Nobody said you had to write the same story they did. And actually, you don’t want to write the same story. You want to put a NEW spin on the story. You want to make it yours. And the options to do this are as endless as your imagination.

You could write a version of Alice in Wonderland that takes place in the BDSM world. Or Romeo and Juliet set 3000 years in the future. You can also invigorate a property by changing up the genre, time, or origin of the character itself. Write a romantic comedy about Dracula. Write a Western about Frankenstein. Turn Cinderella into the bad guy. Or a man! I actually had that idea once, about an average-looking plumber named Syd E. Rella who finds himself at a large charity auction and strikes up a flirtationship with the beautiful CEO of the biggest company in the city.

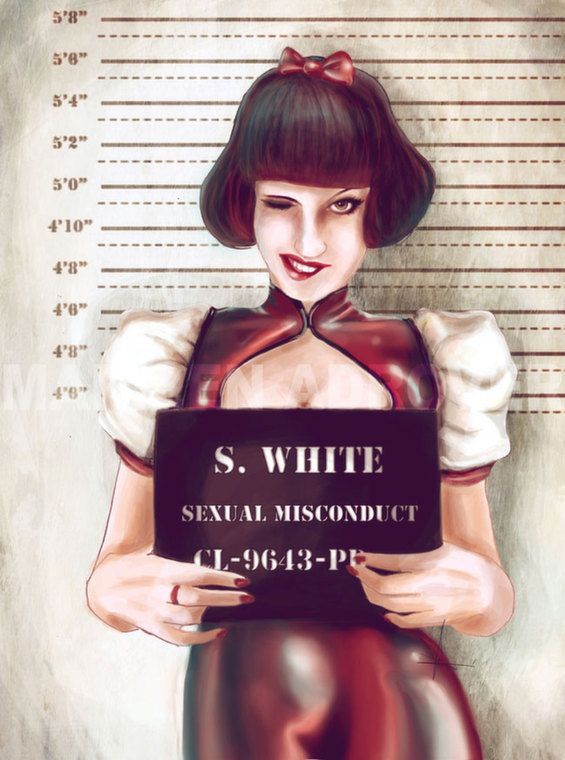

There are so many examples of these scripts selling. There was a dark serial killer script where Peter Pan was the killer and Hook was the detective that sold a few years ago. A script about The Count of Monte Cristo set 30 years in the future that sold two years ago. Snow White and the Huntsman sold for 1.5 million bucks and we all know how much money that movie went on to make. One writer even got creative and went past Pinocchio to focus on his father, Geppetto.

The point being: Let your mind roam free. Find a popular property in the public domain and put your spin on it. I PROMISE you that saying, “I have a script about a bored suburban man who builds a time machine in his basement that’s based on H.G. Wells, “The Time Machine,” is going to get a lot more attention from agents than, “I have a script about a bored suburban man who builds a time machine in his basement” by itself. Whether it’s fair or not, that’s how the business works.

So with that in mind, here are the top 25 works/authors in the public domain. Feel free to suggest any that I missed in the comments section. If they’re obvious ones, I’ll add them.

THE 25 MOST BANKABLE WORKS/AUTHORS IN THE PUBLIC DOMAIN

1) Alice in Wonderland

2) The Wizard of Oz

3) Cinderella

4) Frankenstein

5) Peter Pan (better lay off this one for awhile)

6) Robin Hood

7) Sleeping Beauty

8) Edgar Allan Poe’s work (The Raven, Tell-Tale Heart, etc.)

9) H.P. Lovecraft’s work (selected stuff – do your research)

10) H.G. Wells’ work (The Time Machine, War of the Worlds)

11) Pinocchio

12) Brothers Grimm (Hansel and Gretel, Little Red Riding Hood, Rapunzel)

13) Jules Verne’s work (Around the World in 80 Days, 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea)

14) Mark Twain’s work (Tom Sawyer, Huck Finn)

15) Robert Louis Stevenson’s work (Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, Treasure Island)

16) All the Greek myths (Zeus, Medusa, etc.)

17) Shakespeare’s work

18) The Count of Monte Cristo

19) Dracula

20) Robinson Crusoe

21) Sherlock Holmes (This is touchy one though. Do your homework)

22) Sleepy Hollow

23) The Great Gatsby (just entered the public domain)

24) Gulliver’s Travels

25) Charles Dickens’ work (Oliver Twist, A Christmas Carol, Great Expectations)

My suggestion would be to find one of these characters/stories that appeal to you and then find an angle that’s never been done before. That’s how your script is going to stand out. Feel free to test your public domain loglines in the comments below. Upvote the best ones and who knows, we may just find a few great scripts to write. For more works in the public domain, check out this link here, and this one here. Looking through each list, I’ve already found a handful of ideas I’d want to turn into movies. Richard Connell’s “The Most Dangerous Game?” Sign me up!

A big new juicy sci-fi spec about gravity-loss just sold a couple of weeks ago. I’ll try to keep my feet firmly on the ground as I review it.

Genre: Science-Fiction

Premise: A gravitational anomaly has sucked four-fifths of the world’s population into the atmosphere. A small team of scientists must travel across San Francisco during the phenomena to find the cure before it’s too late.

About: Visionary filmmaker, Matthew Vaughn (Kick-Ass, Kingsman), is taking a rare step into NON-IP fare. That’s right. A major Hollywood filmmaker is directing a SPEC SCREENPLAY. This should give your little screenplay typing fingers some goosebumps cause it means that the SPEC IS BACK, BABY! Okay, maybe I’m hyperbolizing. But it’s still pretty cool. Screenwriter Shannon Triplett sold the script to Fox for mid-six against seven figures. While he worked in some small assistant capacity on Gareth Edwards’ Godzilla, and has done some special effects for movies such as “Journey 2: The Mysterious Island,” this is his first breakthrough on the screenwriting front. Triplett looks to have used some of those effects skills to market his script, including some concept art, which you can find in the screenplay.

Writer: Shannon Triplett

Details: 115 pages

I know a lot of you screenwriting purists hate the idea of concept art in screenplays, but the way I look at it is that there are so many reasons to say no to a project – Like the fact that this movie will cost 120 million dollars and isn’t based on any IP – you need ways to turn the head-shake into the head-nod. One way is to actually show them imagery from your movie.

Now it’s gotta be professional. And I’m going to make a sweeping statement here that’ll be harsh but hopefully save you from embarrassment in the future. Unless you get paid as an artist, DO NOT try to create your imagery yourself. Even if it’s pretty decent, it will look 19 levels worse than the concept art the average studio exec is used to looking at. So it’s just not a good idea. Trust me. I know you’re talented. But you’re not as good as the guy who does it 9 hours a day 360 days a year.

If you’re going to include concept art, you’re going to have to pay some money to get professional work done. Paying money to write a script may sound counterintuitive. But what you have to remember is it’s an investment. You’re investing in something that IMPROVES your chances of selling your script.

It’s up to you whether you think the investment is worth the potential payoff, but if you’re writing some grand scale summer flick that’s never been done before, it might be helpful for the reader to see a visual example of what you’re going for. Who knows? The right image – something that perfectly encapsulates your movie – might be the thing that tips the script-sale-needle in your favor.

Liam West is a theoretical physicist. And no, I don’t know what that is either. But under these circumstances, that title is really important. You see, after two months of global gravity fluctuation, everything starts shooting up into the sky at once.

Liam is able to get to a military bunker with his wife and kids, but his wife isn’t able to make it inside, and is left out in the unpredictable elements of gravity-less San Francisco. Now that is not a San Francisco treat.

After a couple of months, Liam, a group of scientists, and a group of soldiers, decide to trek across San Francisco to Stanford, where an old colleague of Liam’s may be finishing up a cure for the gravity issue.

The group has to use spiked-shoes and mountain-climbing poles to stay attached to the earth, lest they float into the sky like a bundle of birthday balloons. As you might guess, this absurdly imperfect approach (I thought these guys were scientists!) results in a new phenomena known as “Scientists go bye-bye into sky-sky.”

Liam decides, mid-trek, that he wants to see if his wife is still earthbound. So the group detours, only to get attacked by a gravity surviving militia. They somehow escape these gravity bullies, and eventually make it to Stanford. But barely anything there still works, and Liam’s friend only has one risky experiment left to try. If that doesn’t pan out, everyone’s going to be spending their next vacation dodging 747s.

This is how you sell a script if you’re a beginner to intermediate screenwriter. You can tell Triplett is still learning the ropes here. Not enough big shit happens. There isn’t enough urgency. And while there are attempts to create character depth, those attempts are scattered and unfocused. I never had a sense of who Liam was or what his flaw was as a human being. This was even more evident with the supporting characters.

Okay, you say, Carson, so if I’m working my ass off for an entire year to give each of my characters emotionally captivating character arcs, why does his script sell and mine is sucking up viruses on my hard drive?

Quite simply, it’s the concept. This is a big idea concept that gives audiences something they’ve never seen before. And that’s a valuable commodity in the movie business because you just don’t see that kind of opportunity often when you’re buying screenplays.

A way to look at it is like this. Let’s say you’re a basketball GM. And you need to figure out who you’re drafting next. It’s come down to two guys. The first guy is 5’10”, scores 23 points a game, shoots 90% from the free-throw line, and is superb at dishing the ball. The second guy is 6’8”, scores 8 points a game, shoots 60% from the line, and is able to jump out of the gym when he dunks. Who do you choose?

It seems easy. The first guy is a much better all-around player, right? Okay, so what’s the hold-up? I’ll take the first guy. Ehhh, except there’s one problem. The other guy is 6’8”. And 90% of the time, the GM is going to pick the 6’8” guy because even though he’s not as good as 5’10” guy, he has a much higher ceiling. Hollywood sees screenplays the same way. Ascension is not as good as an amateur script I read just last week about a used-car salesman. But Ascension is 6’8”. It has way more upside.

And you have to remember: Hollywood can always hire somebody to beef up the character stuff. This is actually the number one reason you see a script sell for so much money and then a new writer gets hired. That always used to seem ridiculous to me (“You just paid all this money! Now you want to change it??”). But after reading all these script sales over the years, I’d think studios were crazy NOT to do this.

This is why guys like Scott Frank and Allan Loeb and Brian Helgeland make so much money. Because they’re the only ones who truly know how to go in there and add depth to the characters (which is why I told you last week that if you want to break into this business, learn character!).

Which brings us back to Ascension as a script. Was it any good? You know, it was all right. But it was also frustrating. I didn’t get the sense that Triplett really researched what this phenomena would be like. It seems like the planet had months to prepare before the actual gravity-strike hit. So why didn’t they fortify the underground city structures to house the general populace?

Why is it that the best travelling arrangement five of the smartest scientists in the world could come up with was wearing spiked boots? There was a lot of stuff that felt like it was thrown onto the page without much thought (another common thread with young screenwriters – they rarely challenge themselves to go deeper). After watching how far The Martian went to make sure all of its science was spot on, Ascension was stumbling around like it was wearing beer-goggles.

I also felt that not nearly enough obstacles were thrown at our characters. The worst they had to deal with was a steep cliff and a tiny local militia. We just talked about this the other day. If you want to get the most drama out of your idea, you need to hit your hero with “Holy shit how are they going to get out of this?” type obstacles. Not a few stray bullets from people who have never shot a gun before.

So yeah, I had some problems with the script. But I understand why it was purchased. Triplett made the wise decision to enter the draft with the 6’8” guy as opposed the 5’10” one. How tall is your concept?

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Become an internet troll to make your script better! Internet trolls care about one thing and one thing only: tearing things down. While that can suck on the internet, it can actually be helpful when you’re writing a screenplay. After you’ve finished your script, put your internet troll hat on, and go through your screenplay with a troll’s mentality. The idea here is tear your script apart. You do this because the screenwriter side of you is too afraid to face the script’s problems. He’d rather live in ignorant bliss. Internet troll you? He’s relentless! And we need relentless. After the troll’s done, you’ll be able to fix all those weak nonsensical things you were ignoring. Had Triplett used his inner troll, he would’ve spotted a few curious problemos with Ascension.

1) Why aren’t there a lot more people still alive? It seems like all you’d have to do is stay in your home. When you needed to go out, you just wear spike-shoes like the scientists did.

2) If the world knew this was going to happen months ahead of time, why wasn’t a better infrastructure put in place to keep society going?

3) Why is all communication down? Again, they knew this was coming.

4) Why can’t people just live underground? Especially in San Francisco, which has a huge underground metro system.

Can the latest James Bond script win over a skeptical reviewer? Or will it be a spectretacular disaster?

Genre: Action

Premise: Bond goes off on a personal mission to find an elusive character known as The Pale King, only to stumble upon a secret organization known as “Spectre.”

About: What a strange place the Bond franchise finds itself in. It is healthier than Uber’s stock price, making billions of dollars every time it hits the streets, yet the debate over whether its current star, Daniel Craig, is a worthy James Bond or not seems as heated as ever. And let’s not forget that Craig regularly takes pot-shots at the franchise, the only films, mind you, that anyone seems to care about him in. Despite this, less than a month ago, he stated he’d rather kill himself than do another Bond film (although some people have implied this is a negotiating tactic). Then there’s this strange underground movement to make the next James Bond black. If he’s black, great, if he’s not, great too. I don’t know why we HAVE to have a black James Bond though. Why can’t he be Native American? Point being, there’s always so much drama over this character. It’s bizarre. Spectre is written by John Logan, who burst onto the scene in 1999 with his spec script, Any Given Sunday. It’s been rewritten by longtime Bond collaborators Neal Purvis & Robert Wade. And when I say “longtime,” I mean “longtime.” These guys go all the way back to Tomorrow Never Dies, which I’m pretty sure starred Roger Moore. Spectre comes out in early Novemeber!

Writers: John Logan (revised by Neal Purvis & Robert Wade)

Details: October 17, 2014 – 129 pages – shooting script

I usually start a Bond review with my typical Bond spiel, about how I don’t quite get the franchise, about how I loved the opening sequences as a kid, about how I always got a kick out of the villains, but other than that, the movies always seemed like an excuse for set pieces, extravagant locations, and giant spectacle to me. And while I suppose you can make that argument for any Hollywood movie, the reason Bond bothers me so much is because it’s always had the potential to be so much more. And yet it seems content with being just enough.

It appears they’ve tried to repair this in the Daniel Craig years, yet I’m not sure they have. The character is more debonair. The mood is weightier. The cinematography is slicker. But the scripts still feel like a patchwork of transitions to get us from one extravagant locale to the next. I wish they would approach Bond from a “story-first” perspective so we could get something that we’d enjoy in multiple viewings, and not just on the buzz-heavy opening weekend. I’m not holding my breath, seeing as they’re going with the same old writers again. But a man can dream, can’t he?

Spectre starts out in Mexico during the “Day of the Dead,” which as you’ve likely seen in the promotional material is that thing where everybody dresses up like a spooky skeleton, including, in this case, James Bond himself.

Bond is going after some guy that “M” (killed in the last film) told Bond he must kill via a post-mortem video message. Even in death, M’s still giving orders. So after knocking down a few martinis, as well as a few buildings (no seriously, Bond knocks down a few buildings), Bond kills this guy, and subsequently learns about an elusive figure known as, “The Pale King.”

Back at home base, Bond’s agency, MI-6, is combining with agency, MI-5, and the new dual-agency director, “C,” wants to make MI-11 surveillance-postiive. He’s got cameras in every nook and cranny of the building. His mantra is, “What does anybody have to hide?” Uhh, it’s an agency of SPIES! So I’m thinking, a lot.

Bond doesn’t like C, C doesn’t like D, and EFGHILMNOP. Bond’s got his own alphabet to worry about anyway. He heads to Rome to find out more about this Pale King fellow, and runs into the Mexico Guy’s wife that he killed. He quickly beds her (no seriously, he uses the line, “I killed your husband,” and three minutes later they’re making out. I wish I was James Bond. Sigh.), and learns that the key to finding The Pale King is talking to Bond’s old nemesis, Mr. White. Mr. White. Pale King. No wonder they don’t want a black James Bond!

In classic Bond fashion, it starts to become unclear what’s going on after page 70. Bond, for whatever reason, ditches his pursuit of The Pale King and instead heads off to find Mr. White’s hot daughter, Madeline (hanging out in the beautiful snow-tipped alps of Austria, of course). Madeline, who has a really bad daddy complex, starts taking out (and making out) her frustrations on Bond.

The two go on a quest to find something Mr. White was hiding. I don’t know why everybody in this world feels the need to give Bond a mysterious adventure to go on instead of just, you know, TELLING HIM WHAT TO GET. So instead of saying, “Here’s what you need,” they say, “Locate L’American. It is there where you will find your answers.”

Uhhh, okay. But wouldn’t it just be easier if you told me the answer in the first place?

Meanwhile, back at MI-11, C has used his new surveillance technology to snoop on Bond’s rogue mission. He wants to stop him, but instead gets distracted by his current obsession, a super-agency that links up the 9 biggest agencies in the world. If these then join MI-11, we’d have MI-20. And that’s an equation I don’t even think Will Hunting could solve. How do you like them apples? There’s something about using this new cross-agency-surveillance to defeat terrorism, but as you might guess, it’s the agency itself that becomes the terrorist. Or maybe not. Or maybe.

Okay so now that we’ve established how I think all James Bond movies are the same, let’s talk about the one thing that makes them different. Because the truth is, the makers of this franchise know they’re giving you the same meal over and over again. So they need one fresh ingredient, one unique attribute that allows them to say, “Something here is not like the others.”

Any ideas on what that might be?

It’s theme. Each James Bond film comes with a new theme to explore. And the trick they use to find their theme is simple. It’s one you can use yourself for your own screenplays. Identify a current issue in the world. That’s right. The Bond writers find the most pressing issue we’re dealing with every three years and build their movie around that.

So what’s this movie’s theme? It’s surveillance. We are all being watched. Everyone. And we know we’re being watched. James Bond is trying to appeal to as big of an audience as possible, so they choose as big and current of a theme as possible.

Now you may be saying, “Hey, that doesn’t sound so hard. I can do that.” But before you head over to Final Draft, I want to teach you a lesson about integrating theme, and it’s a lesson I’ve learned only recently. Ready? Grand generalizations about whatever theme you’re pushing are worthless. If James Bond drives past a random protest where people are saying, “We don’t like being watched!” it doesn’t push the theme of surveillance in a way that affects the audience.

The only way a theme resonates is if you incorporate it into the plot in a way that directly affects the main character. Then, and only then, do we feel your theme. Spectre does this numerous times but the most obvious example is that MI-6 (Bond’s agency) is combining with MI-5, and the new combined agency director, “C,” incorporates surveillance into the fabric of the agency. Bond can barely walk anywhere in the agency, do anything, talk to anyone, without a camera staring at him. So he is being DIRECTLY AFFECTED by the theme. That’s how you pull theme off, folks.

As for the rest of the script, I can’t say I loved it. The Bond scripts always seem to have this dry rhythm to them that follows the same pattern. Bond is told of a person or thing, so he must go to another country to find said person or thing. He goes there and finds the person or thing, only to be told that he actually needs to find something else in another country. So he goes to this other country where he finds his “something else” only to be told that there is someone who can answer his questions in another country. So he goes to this other country to find this person…etc…etc.

There isn’t a whole lot of skill in that other than coming up with cool-sounding names for what Bond must find (The Pale King, Mr. White, L’American, Spectre). You may as well call these things “A, B, C, and D” though. That’s how basic this practice is. It’s this very transparency that keeps me from warming up to these films.

I suppose it can be argued that the typical audience member is too caught up in the fun locations and set pieces to notice or care about this. Joe Moviegoer has a much higher tolerance for artificiality than Jack Hollywood. I get that. But after seeing the awesome “Martian,” and watching how they mixed that story up and kept you guessing, it reminded me of what’s possible. This mechanically written script reminded me of what happens when you follow the most basic boring plotting practice available to screenwriters:

Hero finds A, is told he must find B

Hero finds B, is told he must find C

Hero finds C, is told he must find D

Hero finds D, is told he must find E.

I really struggle with why people love these films so much. They seem so boring and obvious to me. Is it the wish-fulfillment factor? That Bond is like a God and we all want to be like him? I can’t even get on board with that, as I find him kind of cheesy. In an industry where we have multiple action-franchises doing the global fox-trot (Fast and Furious, Mission Impossible, Bourne), are even the locales that much of a drawing point anymore? What separates this franchise? What makes it unique anymore? Help me out here!

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: There are two ways to introduce theme into your story – direct and indirect. Indirect would be something that occurs in the background and doesn’t affect your hero. So if my theme was about how one-percenters ruled the world and the rest of the 99 percent were fucked, an indirect treatment of that theme may be to show a line of random poor people around the block at the local unemployment office. This conveys my theme, but it does so indirectly, as I the audience member don’t know any of these people. A direct treatment of that same theme would be to have my main character be one of the people in line. You are now expressing your theme DIRECTLY through your main character, who we can see is poor and needs assistance. Put a premium on direct theme. That’s where it will resonate the most.

I know you guys were just DYING for another molly mish-mash mix of masochistic screenplay mayo. Well let me spoon some out for’ya, Martha. Open wide!!!

For those wondering about the short post today, it’s pretty simple. I’m tapped the F out. I’m a Rhonda Rousey opponent 12 seconds into the fight. I’ve got nothing left. My weekend became the classic, “Do all the work you didn’t get done during the week,” scenario. I had grand ambitions of reviewing the Spectre screenplay but instead double-o-sevened myself into a work coma (yeah, that’s a thing now).

I didn’t get a chance to see any movies over the weekend but I have watched a few digital flicks so maybe I’ll tell you about those. Let’s start with Knock-Knock. They should’ve KNOCKED this one to the 99 cent bin because that’s where it belongs.

Knock-Knock is about a married man home alone for the weekend who lets two lost young women in his house, and then shit gets crazy. As in, they fuck. And then he has to get rid of them before his wife and kids come back. The premise for this one is pretty good. You see the conflict right at the top of the logline.

But whereas I used to get excited about these movies, I’ve become hip to their achilles heel. You have three characters. You have one location. You have a conflict that occurs early. You still need to fill up 60 pages of script real estate. And nobody who writes these movies realizes that until they’ve already started. So they get to that page-30 “oh shit” point, realize they have nothing left to write, and then, basically, bullshit their way to the end, hoping nobody notices.

Oh, I notices!

You could see the writers scrambling for plot scenarios like rats scrambling for a fallen piece of New York pizza. The story doesn’t even take place in one continuous timeline. The girls actually leave the next day and then come back a day later. Is it Knock-Knock? Or is Knock-Knock-Knock-Knock? Make up your mind.

The lesson here is to make sure your idea has legs. If a premise only takes you to page 30 (or even 45) before you realize you don’t have anything left to say, you probably shouldn’t write that movie. And, oh yeah, this is another ringing endorsement for writing an outline. Had they written an outline here, they would’ve known they were fucked past page 45.

Next up we have Dope. And I’m sorry, but this movie sucked. I know it’s gotten good reviews but Dope is the epitome of the Sundance flick. It’s got some retro element that makes it “hip,” and the filmmaking is competent enough that it doesn’t embarrass itself. This, it appears, is all it takes to become a “breakout film” at Sundance.

I know there are a lot of first timers coming through Sundance, but I don’t know why we’re celebrating “just good enough to not be embarrassing” as the bar. Don’t even get me started on the lead actor. Had that guy ever acted before??

Let’s move to this week’s crop of box office films. Here’s the top 10:

1) Goosebumps – 23.5 mil (Jumanthura 3)

2) The Martian – 21.5 mil (I love potatoes)

3) Bridge of Spies – 15 mil (sad that Tom Hanks movies don’t open #1 anymore)

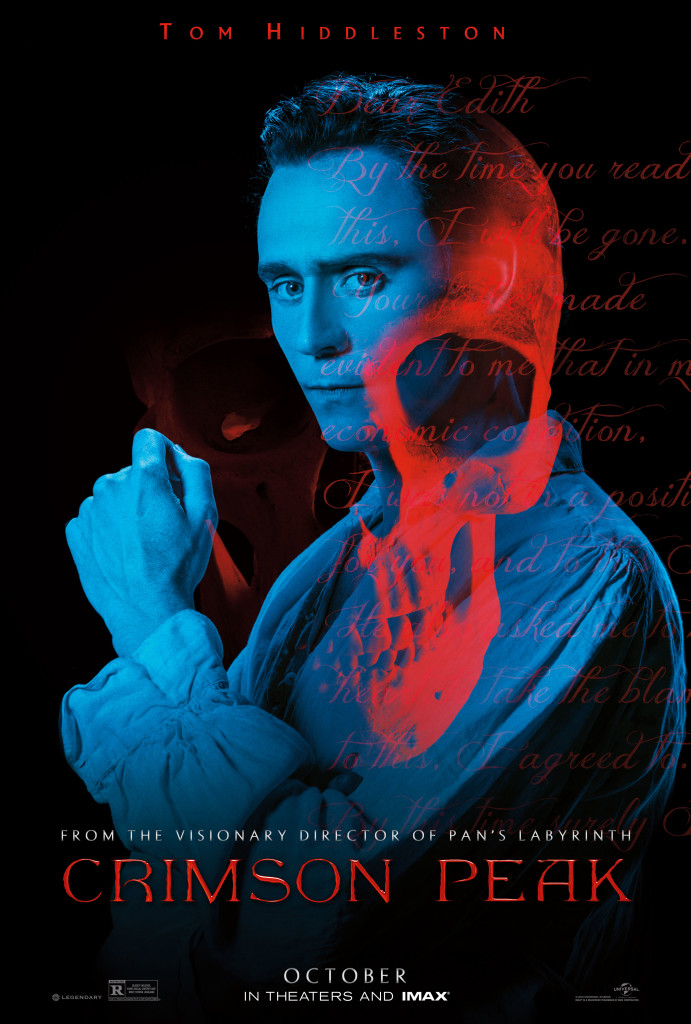

4) Crimson Peak – 12.8 mil (Del Torro overrated?)

5) Hotel Transylvania 2 – 12.2 mil (Adam Sandler needs to stay in the animated space where we don’t have to see his face)

6) Pan – 5.9 mil (studio now optimistic the film will only lose 140 million instead of 150)

7) The Intern – 5.4 mil (anybody else think Robert DeNiro looked confused in this?)

8) Sicario – 4.5 mil (neck and neck with Martian for best script of the top 10)

9) Woodlawn – 4.1 mil (I have no idea what this movie even is, which usually means it’s a Christian movie)

10) Maze Runner: The Scorch Trials – 2.7 mil (but, there’s no maze)

Here’s my take on this weekend’s crop of films. Goosebumps was lucky a real movie wasn’t debuting this weekend. It’s fine for family fare but man did this look safe. I love Jack Black but these days, when a studio wants to play it safe, he’s the actor they hire.

I love that The Martian is still going strong. Such a great movie on every level, from script to direction to acting to effects. This one is going to get some Oscar nominations – no easy task when you’re a sci-fi flick.

I have a very strong opinion about this but movies that have to do directly with the Cold War never do well. And it’s pretty easy to figure out why. Uh, because it’s not a real war! It’s a “cold war.” Which is code for “nobody’s warring.” People nostalgic about the 80s continue to try and make this a thing though, typically with the spy genre, and yet there’s something inherently unexciting about it all, as if nothing anybody does really matters since all the Cold War was was a bunch of people who were too big of wussies to actually get in a real war. Yeah, I said it! I said it! What are you gonna do!!??

And that brings us to Crimson Peak. This failure was the most fascinating for me for a couple of reasons. First, the marketing for this movie was absolutely horrrrrrrrible. Whoever’s decision it was to make billboards that were basically black backgrounds with blue and orange rorschach tests on them easily lost the film 5 million bucks, at least. That was even worse than a Josh Trank tweet. Not good.

But actually, there’s a bigger lesson here, and one that, as screenwriters, we all must hold near and dear every time we come up with an idea. Whenever you write outside of a clear genre, you run the risk of people not “getting it.” When I watched the trailers for Crimson Peak, I wasn’t sure what it was about. If it was a horror film, there wasn’t enough horror! The second an audience isn’t clear on what kind of movie you’re selling them, you’re dead. They’re not showing up. And Crimson Peak showed us on a grand scale just how damning that mistake can be. Universal’s first major misfire of the year!

Okay, time to wait another 10 hours for the new Star Wars trailer. Which reminds me of a joke. What do you get when you cross peanut butter with a Gungan? A peanut butter jar-jar. Heh heh. I actually made that up myself. Like, you can check the internet if you don’t believe me.

p.s. Question for the Scriptshadow faithful. Why do you think Pan failed? There’s something about it that always looked “off” to me, but I’ve never been able to articulate what it was. This was a family film based on one of the most popular and beloved childrens’ characters in history. Why didn’t anyone show up?

Halloween is fast approaching which means this week’s batch includes some spooooooky horror scripts. Oh, who are we kidding. We get four zombie scripts a week. Speaking of horror, has anyone seen Crimson Peak? Any good? Should I review that, Goosebumps or Bridge of Lies for Monday? Okay, I have no idea if any of this weekend’s scripts will be good. But I liked a lot of the “Why You Should Reads.” Everyone here seems serious about the craft. Vote for your favorite script in the comments section!

Title: Made in China

Genre: Dramedy

Logline: Two estranged sisters from New York travel to rural China to receive an inheritance from the father they never knew. Once there, they find themselves on a wild journey of self discovery as they race the clock to pass physical and psychological tests set forth in their father’s will that will earn them his mysterious legacy.

Why You Should Read: I’ve been an avid reader of SS since its inception, and in fact had two of my first [very shitty] scripts privately reviewed by Carson around the same time he moved to LA. The good news is I managed to get both those scripts to a point where they received 7s on the Blacklist and made finalist in a handful of competitions, the bad news is that the concepts were inherently flawed and would never move beyond this, or get me any read requests. — 4 years and 6 scripts later, I finally feel like the new scripts I’m currently tackling could be ‘the ones’. — Made in China is not one of those scripts. ;) But it is the only script I’ve ever pitched to prodcos and actually got read requests from (no callbacks). So, as ready as I am to throw this script in a draw and move on, I feel like I owe it one last chance to find out why the logline appeals (over 2:1 pitch-/request ratio) and where I’m failing to deliver what I promise in the premise. I’m hoping the generous SS community could tear this apart. I like brutal honesty, it’s the only way to grow. :) Thanks!

Writer: Billie Bates

Details: 95 pages

Title: Wet and Wild

Genre: Comedy

Logline: The lives of several young people intersect during the course of one blistering afternoon in July 1991 at a Wet ‘N Wild water park. (Stand by Me meets Dazed and Confused meets Hot Moves)

Why You Should Read: Hi. I’m Derek Williams. Amateur Friday alum. My script Goodbye Gene was reviewed a couple of years ago. Well…here I am again. — My goal with this script was to make an epic Summer movie. I love trashy teen sex comedies from the 80’s. USA UP All Night type of stuff. Yeah they’re bad films, but they have this undeniable spirit. 80’s filmmakers high on the cocaine making T&A flicks. Lol. I also love what Tarantino is doing lately. Playing with genre. — So I thought, “what the hell?” I’ll try and apply that 80’s teen sex genre feel to my next script. — I didn’t enter the Scriptshadow 250 because I was out of the country and off the grid all Summer. By the time I heard about it, the (extended) deadline was two days away. Nope. This script was only at 95% at that point. Had to miss it.

Title: Team Halloween

Genre: Adventure/Sci-Fi/Comedy

Logline: A group of Halloween-obsessed friends stumble across an otherworldly device and turn everyone in town into their Halloween costumes! They team up with a wacky scientist to fight through the chaos, get the device back, and make sure the world doesn’t turn into Halloween for real–forever!

Why You Should Read: Because it’s the perfect time of year for it! And because, in no uncertain terms, I wanted to create a go-to, all-ages Halloween ‘staple’ movie (the kind of movie that you have to watch whenever the season rolls around, like ‘It’s A Wonderful Life’ is for Christmas, ‘Jaws’ is for the Fourth of July and ‘Groundhog Day’ is for Arbor Day), and I wanted to see what the world’s biggest group of smart script-readers think about it! Hardly anyone agrees on what movie they HAVE to watch every Halloween, and almost none of them are appropriate for parents to watch with their kids. I genuinely want a movie that groups of people will get together to watch for decades to come. I want parties dedicated to it. I want the title to become a verb. I want a movie that kids, teenagers, adults–literally everyone–will want to see because it’s funny, smart, thrilling, and touching. It’s a heartfelt return to the glory days of blockbuster movies that know how to have fun. It’s Back To The Future meets The Monster Squad (which was, of course, The Goonies meets Halloween); it’s big, it’s exciting, it’s all-ages (read: FOUR QUADRANT, baby) and it doesn’t overstay its welcome. Plus the title is catchy as hell, isn’t it?

Title: Caina

Genre: Crime Drama (with a splash of comedy)

Logline: In order to escape a debt owed to Irish gangsters, a man disguises himself as his dead twin brother, only to suddenly find himself involved with the Italian mob and DEA.

Why You Should Read: Oh how I long to be a professional screenwriter. To be at a post-Oscars party with a martini in one hand and an actress in the other, slow dancing while the band plays “Midnight Serenade.” Yes, I’m delusional. Anyway, most people who have read this have told me they like it. It recently advanced to the 2nd round (15%) at Austin and I got very nice compliments on it from them. But I have exhausted all rewrites from my brain and compliments don’t help me any. So it’d be nice if you and the Scriptshadow community could tear me to shreds which will be more helpful. At worst, your readers will know what a 2nd round script looks like and compare theirs accordingly.

Title: LRKRZ

Genre: Horror/Slasher

Logline: Deep in the twisted and lawless labyrinth of San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park, a hip sociologist named Vega and her dirty gutterpunk friends are viciously hunted by the Lurkers, a pack of deranged, homicidal hobos — or maybe something even worse.

Why You Should Read: It’s always a lucky day when an idea picks you. Here, I had no desire to draft a horror screenplay, but frequent walks through San Francisco’s parks got me obsessed with what goes on there after dark. I mean, if the City streets are this sketchy during the day, then the nighttime park must be a fucking murder zone. And so the Lurkers were born, and now I’m half convinced they’re real. Definitely dirty business. — I’m more than a little over the current state of horror movies, so this is my effort to take it old school, with a focus on characters and a slow build. But for the shots of San Francisco it would cost little to make, so I hope I can convince an edgy director to take a chance. — Thanks again for all your hard work, Carson, it’s a real inspiration.