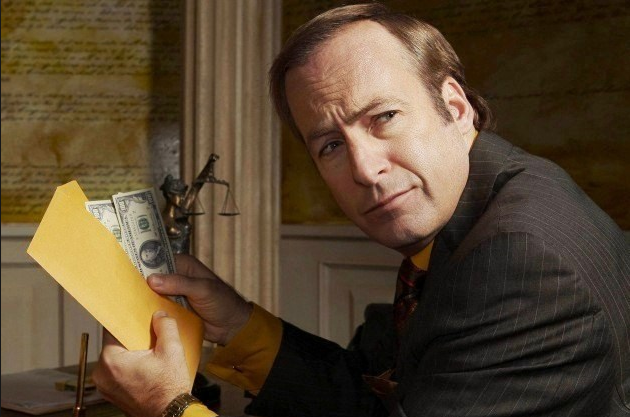

So I recently finished watching the fifth episode of Better Call Saul (this does not include last night’s episode), and I have to say, the Breaking Bad spin-off series has surprised me. Not just because it’s pulled me in, but because the big picture writing on the show is nowhere to be found. This is a show that’s hooked its viewers on an episode-by-episode basis, an unheard of strategy in a serialized TV program. And if I’m being honest, I have no idea how Gilligan plans to keep it up. I mean, Breaking Bad was masterful in its big picture writing. And that got me thinking about the differences between the shows. Why is it that Breaking Bad is so much better than Saul? I’m glad you asked. Because I’ve broken it down into six big reasons. Let’s take a look…

OVERALL STORYLINE

In order for any story to work, it must have an engine. The engine is the thing that pushes the story along underneath the hood. In a feature, that engine needs to rev high and fast (stop the alien invasion, execute the heist). In TV shows, since the story needs to last a lot longer, that engine will rev slower and longer (find a way off the island, find a surviving community in a zombie apocalypse). Breaking Bad had a great overall storyline. Walter White needed to make a ton of money before he died of cancer so that his family would be supported after he died. Every episode in that first season ran on that engine. What’s the overall story engine in Better Call Saul so far? There isn’t one. I guess it’s sort of “Let’s see if Saul can start a business” but that’s hardly in the same engine category as dying of cancer – save my family.

MAIN CHARACTERS

One of the keys to making a TV show work is creating a sympathetic lead. That’s no different from how they do it in the movies. Walt was one of the most sympathetic characters we’ve ever seen. The poor guy had terminal cancer, a son with special needs, a new baby on the way, was the best at what he did, and was an underdog in every sense of the word. He’s a brilliantly conceived character who’s impossible not to root for. Saul is sort of an annoying fast-talker. Vince tries to create sympathy by pushing Saul out of his big corporate law gig, creating another “underdog” scenario in a sense. But it just isn’t the same. We do root for the guy, but it’s more out of curiosity than need. We NEEDED Walt to figure out how to save his family. Also, doing something for one’s self is never going to be as sympathetic to an audience as doing something for others.

DRAMATIC IRONY

Breaking Bad’s single biggest trick was the dramatic irony that was woven into the core storyline. Walt has a secret. He’s a drug dealer. It’s a secret he’s keeping from his family, his work, his friends. And that alone implores us to keep checking in week after week. We want to know, “Is this the week someone’s going to catch on?” “Is this the week he finally gets caught?” Gilligan knows he doesn’t have that with Saul, so he uses other tricks to pique our curiosity, such as Saul’s weirdo brother who believes he’s allergic to electrical impulses and has to live in a house devoid of electricity. It definitely pulls us in at first, but it is, ultimately, a gimmick. And gimmicks can only last so long.

TICKING TIME BOMB

Another factor that worked well for Breaking Bad was that it had a ticking time bomb woven into the setup. Walt was dying. He didn’t have long to live (at least initially). So he had to move fast. There’s no big picture urgency at all in Better Call Saul. This is on full display when you notice there are a lot more “sitting down and talking” scenes. When there’s no urgency, there’s a natural tendency to write more talky scenes because what else are you going to do? Your characters clearly have the time. In an early episode of Saul, the one where the family stole the money, the urgency is there. But in some of these other episodes, it’s not. Incidentally, this is what’s killing The Walking Dead this season. Unlike past seasons (going after the Governor, trying to get to Terminus), there’s little-to-no engine driving the season, and because of that, no urgency. It isn’t a coincidence that all the characters are now sitting down and having long talks with each other that bore us to pieces.

CONFLICT

Another genius move by Gilligan in Breaking Bad was creating this “buddy cop” scenario (with Jesse Pinkman). Two completely opposite personalities who are forced to work together to achieve the same goal. You know instant oatmeal? By creating a “partners who hate each other” scenario, you get instant conflict. You never have to come up with some artificially constructed scene to create contact. It’s built into the key character relationship so it’s always there for you. One of the reasons Better Call Saul feels slower and quieter than Breaking Bad is that it lacks this component. Saul’s only real buddy is Mike, and Mike isn’t exactly a talker.

PROGRESSION

One of our favorite reasons for tuning into Breaking Bad every week was the progression. We loved watching Walt and Jesse move up the ladder, particularly because it was a world they had no business succeeding in. There was something delightful about a chemistry teacher becoming the best drug dealer in the city. This is the one area that Gilligan is trying to match in Better Call Saul. He’s hoping we’ll get involved in Saul moving up the ladder and becoming a successful lawyer. The big difference here is that a) Walter’s rise was ironic – a nerdy chemistry teacher becoming a badass drug kingpin. Saul’s rise is pretty straightforward. A low-rent lawyer trying to make a name for himself. And b) We already know where Saul ends up – in some rinky-dink operation in a strip mall. Whereas with Walter, the possibilities for success were endless, we can never experience that with Saul (which is why I hate prequels – but that’s a story for another article). I suppose Saul could rise before he falls, but we still always know where he ends up.

Now I point all this out not because I want Saul to fail. I actually desperately want the show to succeed. There isn’t a lot of quality television out there and I like this universe Gilligan has created. Still, I’m fascinated, from a writing standpoint, with how Gilligan plans to make this work. The first series of episodes have been solid on an episode-by-episode basis. But like I said, to get an audience invested in the long term, you need to give them a peek under the hood. You need to show them the engine. And I don’t see that yet – or at least, I don’t see an engine strong enough to keep this car running all the way to the finish line. TV shows, way more than movies, need to be built atop solid foundations. If the plan for the show isn’t known, writers eventually must resort to tricks and gimmicks (big twists, main character hookups) to cover up the fact that they have no idea what to do next. This is why certain shows that were good at first (Prison Break, Heroes) went off the rails quickly.

For those who’ve seen the show, do you enjoy it? Why do you watch it? Do you agree that there seems to be a lack of a master plan? Does that bother you? Chime in below. I’m curious as hell to know what you think!

Genre: Sci-fi

Premise: In the near future, an engineer creates an artificially intelligent robot. But when a group of criminals kidnap the robot and use it for their own nefarious purposes, things go downhill.

About: Neill Blomkamp was plucked out of obscurity by the then biggest director in the world, Peter Jackson, to direct the Halo movie. While at first skeptical, audience reaction changed when Blomkamp’s test movies and short films leaked online. The young auteur had a knack for creating amazing special effects on tiny budgets. Halo didn’t happen but that turned out to be a blessing in disguise when Blomkamp switched gears and gave us an original film instead, District 9. With no stars and an unfamiliar setting (South Africa), box office trackers dismissed it. The film would open with a shocking 40 million dollars on its opening weekend, though, and a new Hollywood golden boy was born. Blomkamp immediately went to work on his next film, Elysium, this time with a budget 5 times as big as District 9 (I’m sure a lot of that went to Matt Damon). Blomkamp reportedly clashed with the Hollywood-style of filmmaking, voicing frustrations after the fact that there were some people out to get him. Whatever the case, the film did okay (around $100 million) but wasn’t loved by fans or critics nearly as much as District 9. Chappie seems to be Blomkamp going back to his roots, returning to South Africa and doing this one away from the system. Unfortunately, the film is not getting the kind of attention he hoped for. It’s currently at 30% on Rotten Tomatoes, and only made $13 million this weekend, its inaugural frame.

Writers: Neill Blomkamp and Terri Tatchell

Details: 120 minutes

I’m one of those people who thought District 9 was borderline genius. It not only took a dated idea and turned it on its head (instead of aliens coming to earth and attacking us, they came here and we enslaved them), but it took a huge risk in how it presented its story, doing so in a documentary format. To take an “artsy” approach on a summer blockbuster is unheard of. As if that wasn’t enough, D9 made its lead character extremely unlikable. I’ll never forget one of the earliest scenes in that film where Wikus delights in the sound of a bunch of alien baby eggs popping after the military sets them on fire.

So I was a little confused when Elysium came out. District 9 felt so deep and extensive. Elysium’s story was so half-baked, I’m surprised Ben and Jerry didn’t sponsor it. Surprisingly, Blomkamp admitted as much in a recent interview, where he copped to falling in love with the imagery of this space station above earth and not really thinking beyond that. The fallout from that decision inspired him to re-hire his co-writer from District 9, Teri Tatchell, for Chappie. This one was going to be different, Blomkamp demanded. And it was. But was it different good or different bad?

Gangsters Ninja and Yolandi need to come up with 20 million dollars in 7 days or a much bigger gangster will kill them. Their idea is to kidnap the lead engineer of the city’s robotic police program, Deon, then hold the city hostage with his power over the robots until they pay up.

It just so happens that when they kidnap Deon, he’s working on a new experiment – the first fully A.I. robot. Ninja and Yolandi change their plan, figuring they can teach this robot to become a gangster and help them pull off a mega-heist.

They quickly name the robot, “Chappie,” and start raising it like a child. Chappie is torn in multiple directions as Deon tries to teach it art, Yolandi tries to teach it compassion, and Ninja tries to teach it to kill. Ninja wins out, convincing Chappie to help him with the heist. But when Chappie learns that the battery inside of him will expire in five days and he’ll be gone forever, he must rethink his priorities, including what it means to be alive.

The first thing I’ll give Blomkamp credit for here is that he’s trying. This is a much more personal story for him than Elysium. And bringing on a real screenwriter has given the script a more polished feel than his last effort. We have clear goals here (pull off the heist), every character has a clear motivation, there are ticking time bombs (deadline to pay back the rival gangster).

Yet still, this feels a few drafts shy of what it’s trying to be. Let’s take a look at why.

NO MAIN CHARACTER

I was just talking about this on Friday. Who’s the main character in this screenplay? Is it Yolandi and Ninja? They’re treated more like plot points than people. Is it Deon? He’s definitely the most sympathetic, but he’s only occasionally around. Is it Chappie? Not really. We almost always see the scenes through the eyes of those around Chappie – not Chappie himself. So who’s the freaking protagonist here?

I’ll repeat this until the brads come home. AUDIENCES LIKE TO IDENTIFY WITH A SINGLE PERSON. They like to latch onto someone and see the story through their eyes. It gives them a sense of comfort. When you don’t give them that, it’s hard for them to connect with the story on an emotional level. It’s the difference between playing a video game and watching someone else play a video game. In one case, you are the character. In the other, you’re just watching a bunch of things happen. Go back and look at District 9. Is there any doubt who the main character was there?

STUCK IN ONE PLACE

Audiences don’t like being stuck in one place for too long UNLESS there’s an inherent desire to get out of that place or there’s sufficient enough conflict within that place to carry the story. Half this movie was four characters hanging around an old building talking. Chappie was learning. So, technically, we’re moving forward in that sense. But then we’d come back to the place and Chappie would learn again. Then we’d come back and Chappie would learn some more. We were never moving forward back at the building so it got boring fast. Look at E.T. E.T. wanted to go home. It was fun at Elliot’s house for awhile. But soon he realized he needed to get out of there – to go back to his ship and get home.

LAPSES OF LAZINESS

It’s never fun to weed out and solve those nagging smaller story problems. You’ve got the big ones taken care of, so the temptation is to call it a day. But if you really want your script to shine, you have to solve the small nagging issues.

Why, for example, is Deon allowed to LEAVE? This guy has access to every single cop in the entire city. Some might say he’s the most powerful man in the city. Yet Yolandi and Ninja are like, “Eh, leave us alone,” and kick him out!!?? That makes NO SENSE.

Then there’s this plot point where Chappie’s battery dies in five days. And this battery is “hard-wired” into him. So it’s not replaceable. Uhhhh… WHAT??? What about all the other robots walking around the city? How do they last for more than five days?

Guys, I know it’s less work to just ignore these things. And it’s true that one or two lazy lapses won’t get noticed by the average audience member. But three? Four? That’s when the audience starts picking up on the laziness. And once they sense that you’re not trying, they’ll never forgive you.

There’s one final problem with this script and it’s something we never talk about on the site because I rarely encounter it. This movie should not have been rated R. This is PG-13 subject matter all the way. It is about a ROBOT THAT LEARNS. There’s no way you can convince me that that storyline requires an R rating. Not only does it limit your box office, but it confuses your potential audience.

Case in point, I had a family sitting next to me with 2 young children (both around 6) who left midway through the film when a porno appeared on one of the character’s televisions. Obviously, that mom and dad saw a fun robot on a poster with the kid-friendly name, “Chappie,” and thought it’d be a perfect film for the family. Turning it into some hard-edged gang war confused everyone and, frankly, doesn’t make sense. So definitely know your subject matter and what kind of rating that’s going to inspire and write according to that rating.

[ ] what the hell did I just watch?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the price of admission

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: A ticking time bomb can’t just be stated, it must be utilized. Ninja and Yolandi have 7 days to find their money or they will be killed (ticking time bomb) by another gangster. However, the two spend the next 90 minutes of the movie sitting around talking. Just STATING that a bomb is looming does not give one license to do nothing until said bomb goes off. Your characters must act in accordance with the looming threat. We must see the fire under their ass pushing them to desperately solve the problem. If you inject a ticking time bomb yet your characters never act like there’s a ticking time bomb, then it’s the same thing as not adding one at all.

As the Scriptshadow 250 Contest looms, contenders wisely sharpen their screenplays with feedback from the community. Help them make their scripts as good as they can possibly be. And to those writing in solitude, best of luck. Can’t wait to see what you’re cooking up!

TITLE: Dating Jennifer

GENRE: Romantic Comedy

LOGLINE: Working as an elementary school teacher can be very hard for Greg, a single parent of one, but when his friends enter him into a contest to date Jennifer Aniston, he gets more than he bargained for.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: I am an aspiring writer, looking to make a splash. I have been teaching 3rd grade students Reading/Language Arts for 11 years, teaching the basics of story, plot, theme, etc. and that has always been a passion of mine. I started getting into writing screenplays in college, but never really got into it until four years ago, completing a script I started back in 1997. But in my case, my first is my worst – it has a good story, but the characters are weak. My second script, I continue to retool. My third script, “Dating Jennifer” is finished and was just named a semifinalist in the Nashville Film Festival (finalists chosen next Friday 3/13 – hope I’m not jinxing myself). Anyway, I’ve also entered it in the usual big competitions, Scriptapalooza, Page, Pipeline. However, I just read an article about your site and would love a review – kind of wish I found out about it before submitting it to some of those competitions. Going forward, I’d love to have some real criticism on it.

TITLE: Monsters Under the Bed

GENRE: Thriller/Drama

LOGLINE: A salt-of-the-earth father, trying to leave a checkered past behind him, is put through the ultimate test when his estranged son gets in deep with a human devil in the Appalachian woods.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: My 6th spec, feeling like it’s all coming together now. Taking an honest look at my writing prior, it would be easy to say I was trying to write “the next great American story” (large, sweeping political storylines, obtuse, lush descriptions, “profound” dialogue) and this time, I’m just trying to write a movie. I hit a lot of things this site discusses: race against the clock, continually mounting problems, clear stakes and goals, a memorable villain and short action descriptions which I think makes for a fun and quick read. Recent films like BLUE RUIN, THE ROVER, and A WALK AMONG THE TOMBSTONES have rejuvenated my passion for writing gritty thrillers.

TITLE: The Shittiest People In The World

GENRE: It’s a fucking comedy.

LOGLINE: An ex-con and his hipster nephew kidnap an obnoxious housewife on the orders of a crooked judge, but when her shady financier husband refuses to pay the ransom it sets a dirty cop and the worst hitman on the planet hot on their tails.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: I’m an asshole and so is my co-writer. They said “write what you know” so we wrote a script about a bunch of assholes. Why should you read my script? Because you’re probably an asshole, too, and would enjoy it.

TITLE: Scare Fair

GENRE: A Coming of Age Horror Romantic Comedy

LOGLINE: A high school senior tries to win the heart of the girl he loves while avoiding various killers at a local horror fair on Halloween Night.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: Sam and I are best friends. We have known each other since we have been kids and have always appreciated films of just about every genre and especially enjoy films which subvert expectations. We know this script will surprise you and impress you while you enjoy the twists and turns it provides. Scare Fair is fun and scary (with some depth)–the perfect components to a horror film.

TITLE: Echoes

GENRE: Supernatural Thriller

LOGLINE: On the run from two ominous stalkers, a woman’s bizarre visions of a pair of 1930s murders lead her and her mysterious new friend to danger and answers in the Mississippi Delta.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: I’m a prolific writer (20 features) addicted to screenwriting and I placed in the 2014 Nicholl Semifinals with a different screenplay. I believe I have a problem in that I finish a first draft and then follow up with a minor rewrite or two before I move on to the next idea – leaving that newborn script unfed, crying, and wallowing in a shitty diaper. I’m looking for some feedback on this one – which is somewhat of a “structural experiment” for me as it’s told in two stories, with the first one playing forward and the second one playing backwards, meeting in the middle at the end. Help me change this script’s diaper and stick a wet nurse’s breast in its mouth.

Get Your Script Reviewed On Scriptshadow!: To submit your script for an Amateur Review, send in a PDF of your script, along with the title, genre, logline, and finally, something interesting about yourself and/or your script that you’d like us to post along with the script if reviewed. Use my submission address please: Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Remember that your script will be posted. If you’re nervous about the effects of a bad review, feel free to use an alias name and/or title. It’s a good idea to resubmit every couple of weeks so your submission stays near the top.

Genre: Western

Premise (from writer): A grizzled alcoholic travels by hook or crook across the Old West to bury his brother but is hunted by those he’s wronged all the way.

Why You Should Read (from writer): Last time I was here, I was dominated by the Benny Pickles script “Of Glass and Golden Clockwork” and deservedly so. Despite not winning the coveted Friday slot, I was still given a TON of awesome advice on how to better my script (Monty), and was subsequently a Top 10% in the Nicholl Fellowship. Not huge accolades, but for my first screenplay? It felt good! — This is now my third script and I feel like I’ve gotten better since I submitted last. But this is a Western, damn it, and nobody wants them anymore. It truly needs to be the absolute best it can be to get any sort of traction. I really hope that the ScriptShadow community can help me again whether I move beyond AOW or not.

Writer: Benjamin Hickey

Details: 97 pages

Can we bring Paul Newman back for this one?

Can we bring Paul Newman back for this one?

Are you a writer who loves Westerns?

Are you frustrated by Hollywood’s disdain for the genre?

I’m going to help you out. Find a fresh angle. Mix a Western up with another genre. Something it’s never been paired with. Take an idea that would normally have nothing to do with Westerns and infuse it into a Western. This is the only way you’re going to make a Western spec stand out.

That’s not to say you can’t write a Western the traditional way. True Grit did well a few years ago. Jane Got a Gun is coming out later this year. But the best way to get Hollywood’s attention is to explore a genre in a way that it hasn’t been explored before. Westworld is a perfect example. Once as a film and now as a show coming to HBO. Surprise us with your Western take.

Where does Oakwood fall on the Surprise Scale? Well, I’ll give the script this. It’s different. Not different in the way I was just explaining. More like different in the way going backwards on a roller coaster is different. Confused? I’ll do my best to clarify.

It’s the old West. An alcoholic drifter named Hearse, so named because he wheels a casket around wherever he goes, is in the market for a horse so he can travel to another town and bury whoever it is who’s in this coffin. But when a local rancher won’t give him a good deal on a horse, he shoots the rancher and takes the stallion.

What Hearse doesn’t know is that the rancher’s wife, Emma, who’s fucking the stable boy when all of this goes down, is one vengeful little lady. She grabs her stable boy, the slow-witted Wally, and tracks Hearse to the next town.

Now Emma never actually saw Hearse, so her plan is to wait by her horse, which has been parked outside the bar, and shoot whoever comes to claim it. Problem is, Hearse figures this out and sends the town drunk to the horse instead. Emma and Wally mistakenly shoot that man, think they’ve avenged her husband’s killer, and go home.

I hope you’re following so far cause this is where things get crazy. It turns out that the man Emma erroneously killed was a member of the notorious Winchester 7. This nasty gang is led by Jackson, a deputy who kills first and asks questions…well, never. And Jackson, like Emma, isn’t the kind of person who just lets murderers go. Hence, he and the gang go off to kill Emma.

The thing is, Emma’s able to kill the first Winchester who gets to her. This helps her realize that she originally killed the wrong man. So she and Wally go BACK to the town AGAIN to kill Hearse, who she now knows to be the true murderer. In the meantime, Hearse kills a Winchester 7 as well (for a badass gang, their guys sure do die easy), meaning he’s now a target too.

This means that Emma and Hearse will have to team up to defeat the rest of the 7, with an agreement that once they’re all taken care of, it’s a showdown between the two of them, where only one will come out alive.

Phew!

You guys get all that?

Okay, a couple of initial thoughts here. I love that Oakwood is a lean 97 pages. I’m a big advocate of WASO (Writers Against Script Obesity) and I’ve noticed that a lot of Western writers over-share when it comes to words. Oakwood’s lean writing style helps move the story along quickly.

Hickey was also very aggressive with his plotting. It seemed like the script changed direction dozens of times, leading to an impossible-to-predict storyline. I have to give it to Hickey. I rarely knew what was going to happen next.

But this is also where I began to take exception to Oakwood. Something about its unpredictability made it hard to engage in.

Before we even get to that, though, I’d ask Hickey, who’s the hero here? Is it Hearse or is it Emma? Hearse is introduced first but he’s such an unlikable person (he gets shitfaced drunk all the time – steals a man’s horse then kills him) that you’re convinced the hero has to be someone else.

The thing is, Emma’s not that likable either. She’s introduced banging the stable boy while her husband is outside getting murdered. This leads to a baffling development where Emma recruits the man she just cheated on her murdered husband with to avenge her husband’s death.

How am I supposed to root for either of these people?

We spend the rest of the screenplay jumping back and forth between Hearse and Emma’s point of view, all the while trying to figure out whose story it is.

And look, I’m not saying you HAVE to have a single protagonist in every script. But if you do have two, your story will be twice as difficult to tell. And furthermore, if you make both of those protagonists unlikable, you’ve made your story four times as difficult to tell. This is the predicament Oakwood finds itself in.

What’s funny about this script, though, is that it never completely falls off the rails. Every time you’re ready to dismiss it, it reels you back in. It’s a little like Jason from Friday the 13th in that sense. You can’t kill him!

Take Jackson, for instance, – the most evil Deputy in Western history. He enters the script around the midpoint and he’s so nasty (he shoots his boss dead in cold blood) that we won’t be satisfied until we see him go down.

This rejuvenates our deadbeat protagonists, whose unlikableness we’re ready to forgive for as long as it takes to turn Jackson into tumbleweed stew.

And then there’s the dialogue, which is pretty darn good. Emma’s admission to Wally after realizing she shot the wrong man results in this great line: “I think we need to be a bit more careful who we put bullets in.” Or when a fellow Winchester 7 seems frustrated that Deputy Jackson would consider this “little girl” (Emma) dangerous, his response is perfect: “I know that little girl is a human being. What I know about human beings is you put them in certain situations and they’re all dangerous.”

There’s no question that there’s something here and that Hickey is an interesting writer. But three things are holding this script back.

1) It’s not clear who the protagonist is.

2) Neither of our dual protagonists is likable.

3) The plot jumps all over the place.

You can get away with one of these in a screenplay. If you’re a skilled writer, you may even be able to get away with two. But I don’t think you can get away with all three. And that’s where Oakwood’s problem lies.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Hickey makes an interesting choice here to reveal his protagonists’ sympathetic qualities late in the script. This is a risky move because readers tend to form definitive opinions on characters early. So if you introduce a character being an asshole, we’re going to dislike him. By the time you reveal that there are legitimate sympathetic reasons for him being an asshole on page 75, it may be too late to change our minds. To combat this, you have to give us at least SOME positive qualities in the meantime. Give us SOME reason to root for this person as the plot unfolds.

Hey guys. Today is going to be a short post as I’m super busy. But basically I wanted to talk about scenes. So much of what we discuss revolves around concept, structure, and character. But the reality is, we have to write 60 scenes in a screenplay. And if you don’t know what to do inside of a scene, it doesn’t matter how good your concept is, or your structure is, or how your characters are.

Now I will put a disclaimer on here that there’s no such thing as a rule that applies to everything. Obviously, there will be exceptions. But this rule should be utilized a ton. You see, as I’ve opened up a couple of early entries for the Scriptshadow 250, I’m seeing a scary trend. The scenes are boring. They sit there. There’s not a lot going on. It’s the dreaded case of “nothing happens.”

Luckily, today, I’m going to teach you a trick where you can make sure this doesn’t happen to you. All it entails is that in each scene, you add a problem. That problem will lead to conflict, which will result in drama. And as you all know, drama is entertainment.

To see this in action, go back and study your favorite films. I guarantee you that in 95% of the scenes, there will be a problem.

The best script to see this in action with is the greatest spec ever written, American Beauty. Nearly every scene in that script introduces a problem. Lester is on a sales call at work but the person doesn’t want to buy anything. PROBLEM. Lester is called in to see his boss, who tells Lester that he’s firing him. PROBLEM. The family tries to have dinner together until the daughter complains about the music they have to listen to all the time, which leads to an argument. PROBLEM. Even tiny scenes, like Lester going to the car in the morning introduce a problem (Lester dropping his briefcase, spilling the contents everywhere, making everyone late).

In a more recent film, American Sniper, the opening scene has Chris Kyle trying to decide whether to shoot a child. PROBLEM. When he gets home, his wife is in bed with another man. PROBLEM.

If you go back further in film lore to Star Wars, the opening scene has the Empire capturing and boarding the Rebel ship. PROBLEM. When R2-D2 and C3PO land on Tantooine, they have no idea where to go. PROBLEM.

One thing to remember is that the problem doesn’t always have to happen to the hero. The problem can happen to anyone in the scene. So, again, in Star Wars, when we finally meet our hero, Luke, he’s buying droids from the Jawas. But the problem occurs from the side of C3PO. He’s been purchased but it looks like he’s going to be separated from his friend, R2-D2. PROBLEM.

Once a problem is introduced into a scene, so is uncertainty. And uncertainty creates curiosity in the reader/audience. People have a natural inclination to keep reading to see how the problem gets resolved.

Let’s say I have a scene between Joseph and Cara, who are on a first date. Let’s say it happens at a diner. In it, the two talk about their likes and dislikes – a typical “get to know each other” scene. There’s nothing particularly wrong with this scene, especially if there’s some interesting revelations about the characters’ pasts, or if the dialogue is witty and clever.

But you can do all of that AND engage the reader by adding a problem. Maybe, for example, Cara’s crazy ex-boyfriend shows up unexpectedly. He asks her where she’s been and why she hasn’t been answering his phone calls. He then turns to Joseph and demands to know who he is. PROBLEM.

Now there are situations where you want to hold back on the problems. For example, let’s say you’re going to kill a character off in scene 4 of your script. You might want to use the first three scenes to build up an idyllic life between that character and our hero. In this case, there’s a deliberate strategy to creating a problem-free sequence – so that the death impacts the audience that much more when it happens.

But I’d recommend adding problems into even those scenes. They won’t be as big as, say, the Empire boarding a Rebel ship. But even the smallest problem leads to conflict and conflict is always going to liven a scene up.

So the first thing I want you to do with your Scriptshadow 250 script is to go through each and every scene. Is there a problem in each of those scenes? I’ll repeat what I said before. There doesn’t HAVE to be a problem in every scene. But if a lot of your scenes are lacking a problem, I can almost guarantee that your script is boring.

Problem-free scenes tend to happen most when the writer is setting up his characters or writing a lot of exposition. They believe they have a right, since screenwriting is hard, to dribble out boring scenes during these moments. I’m here to tell you that that is a BAD IDEA. You don’t get to take scenes off, no matter how hard they are to write. Go into those character intro and exposition scenes and find a problem to add. I guarantee you the scenes will be better.

Also remember that each problem should vary in intensity. Don’t try to write some earth-shattering problem into each and every scene or you’ll exhaust the reader. A problem could be as simple as your character goes to get coffee and someone cuts in front of him. PROBLEM.

Or maybe the barista gives your character the wrong coffee and he has to go back in line. He, then, could be the person who has to cut others. But everyone tells him to get back in line. PROBLEM. Add a time constraint (he has to be in a big meeting in 5 minutes) and now you have yourself a scene. It really is that simple.

The reason this trick works is because characters become the most interesting when they’re forced to act. That’s when we learn the most about them. By introducing a problem, you force your character to act. And however they choose to react tells us loads about them, in addition to creating conflict in the scene, in addition to making the audience curious about what’s going to happen next . To that end, this might be considered a super-tool. Go ahead and use it in your scenes and report back in the comments on how it went. Good luck. And keep working on those Scriptshadow 250 scripts!