ATTENTION: THE SCRIPTSHADOW NEWSLETTER HAS BEEN SENT – Check your Spam and Promotions Folders if you did not receive. Hope you enjoy it!

Genre: Cray-Cray

Premise: When humanity discovers a human on Mars, they bring him home, where he learns all about the peculiarities of earth.

About: This adaptation of the classic sci-fi novel was written in 1995 specifically as a vehicle for Tom Hanks (this would’ve been right after Forrest Gump). The script was written by Dan Waters, who became a screenwriting sensation after the cult film everyone in Hollywood loved, Heathers. Waters wrote Batman Returns and Demolition Man in 1992, but has had trouble finding credits since (his most recent film is Vampire Academy). Paramount, who commandeered the project, seems set on bringing these old sci-fi novels to life, as they just bought the rights to The Stars My Destination last week (another Heinlein novel). Robert Heinlein is a legend in the sci-fi community, penning tons of books, including the sci-fi classic, Starship Troopers. Don’t tell Paul Verhoeven (who directed the film version of Troopers) that though. The director is said to have never read the book: “I stopped after two chapters because it was so boring,” he said. “It is really quite a bad book.” He later asked a friend to just explain it to him.

Writer: Dan Waters

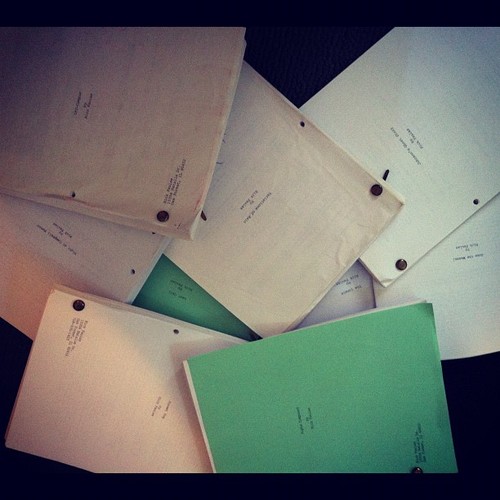

Details: 156 pages! – 5/22/95 draft

Before you read this review I need you to go to Amsterdam, locate the nearest Mushroom store, and buy as many mushrooms as you can afford. Eat them. Then, and only then, will you have a chance at understanding this screenplay and my review of it.

I’ve read some fucked up stuff in my day. But this is the kind of script that makes David Lynch look like John Lee Hancock. I’m pretty sure I know why Tom Hanks passed on this. Because he couldn’t find a translator to make sense of it.

This is Birdman meets sci-fi meets Forrest Gump. Which may sound delightful to some of you. But I’m warning you. After you read this, there’s a 14% chance you may no longer understand the English language.

Stranger in a Strange Land starts when our first expedition to Mars ends in us finding a naked man running around the red planet with a bunch of rock monsters.

Mmm-hmmmm.

Okay.

The Marstronauts grab the human Martian, named “Mike,” and bring him back to earth. This new earth is very different from the earth we know now. While we no longer have war, the government’s been globalized, and radical religious leaders have become the most important figureheads on the planet.

A female reporter, Gillian, sneaks in to the hospital to get a story on Mike, then ends up stealing him and the two go on an adventure together. Where? To Jubal Harshaw’s house of course. Who’s that, you may ask? An ex ghost writer. And physician. And lawyer. Who now owns a hippy compound.

Sure. Why not?

What happens next? Well, by all measurable accounts , absolutely nothing for the next 40 pages. We just hang out at Jubal’s house where Mike, who speaks some gibberish form of English (“You happy me very,”) reads books and learns about humanity!

Eventually, a “sort-of” plot emerges where we learn that Mike’s parents, who owned a billion dollar corporation, died in a mysterious plane crash and the World Organization took over their company. With Mike being the son, he’s technically the heir to that fortune, which means the WO may have reason to turn him into rock food.

What happens next may or may not have something to do with group sex. And death. And people eating the dead. And speaking to people from the afterlife. I can neither confirm nor deny that there are three scenes that actually make sense in this script. Or that an ending that actually wraps things up exists. You will have to read the script yourself to find out. Please report back to me once you do. Insanity hurts.

I’m not going to lie. After finishing this, I wasn’t sure the writer had ever written a screenplay before. Or anything for that matter. If this was a menu, it would’ve started with the instructions for building a treehouse. And it would’ve been in Chinese.

As an experiment, I read five pages of this script out of order and then five pages in order. The five pages out of order made slightly more sense than the consecutive ones. Which should tell you what you’re in for here. Since it’s hard to know who’s responsible for the incomprehensible nature of the story, because I’ve never read the novel, I’ll just assume that both of these guys are off their rockers. I mean, who the hell were the people celebrating this novel when it came out? CIA-obsessed transients who mumble the ingredients of ketchup to themselves at the Santa Monica McDonald’s?

While I could probably key in on 184 things that were wrong with this screenplay, I’ll start with an obvious one. If you’re going to center a story around a man who’s supposedly different from everybody else, you probably don’t want to make everybody around him just as crazy as he is. By doing so, the character doesn’t stick out at all.

Indeed, Mike is swallowed up by this screenplay. In the first 70 pages, he gets about 15% of the screen time. Instead, we focus on hippy-extraordinaire, Jubal Harshaw, a name that could only have been conceived with the influence of at least a dozen hallucinogens.

And then there’s the structure, or lack there of. Look, we all know that books go on for longer than screenplays. This is why they bring in screenwriters to adapt novels and not novelists. Because screenwriters specifically know how to cut stuff down and focus on the things that matter. They know how to EDIT.

Dan Waters never got that e-mail. This is 157 pages of Wanderosa, heavy on the random. Why in the world would you write a 40 page sequence at a man’s house without a single plot point pushing the story forward? I can find absolutely no excuse for this.

The core of every screenplay is the character goal. It’s giving your protagonist something they’re after and then pushing them towards that something. If you don’t do that, you’re going to end up with a screenplay that goes nowhere – that lasts 157 pages. Even in the most optimistic scenario, where this is an exploratory first draft, there was no attempt by the writer to rein in this story at all.

And it doomed them. If you’re Tom Hanks and you read this, you see your character featured 5 times in 70 pages and you don’t start putting together notes for the next draft. You say, “See ya later.” You have to at least put the illusion together that you tried. Any schmoe off the street can write a bunch of random thoughts for 157 pages. Skilled screenwriters are the ones who can find the core of a story and build a structure around it.

Or maybe… maybe Waters knew this was doomed from the get-go. There is something in production circles known as “suspension of disbelief.” If the audience can’t get past the artificial reality you’ve created, it doesn’t matter what you write. Is there any scenario under which a naked man running around on Mars with rock alien brothers is going to work? Probably not. So Waters just said, “Fuck it. If I’m going nuts, I’m going nuts all the way.”

It just goes to show that some properties aren’t meant to be turned into movies. Although maybe this is another opportunity to explore angles, like we did last Thursday. Might the Scriptshadow community have an angle for Stranger in a Strange Land that actually works? Share your thoughts in the comments section. In the meantime, I’m going to go research lobotomies.

Script link: Stranger in a Strange Land

[x] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: For you writers out there who don’t believe in outlining, READ THIS SCRIPT. This is what happens when you don’t outline.

Scriptshadow readers try to sharpen their scripts before the Scriptshadow 250 Contest. Let me know what you think!

TITLE: Quilted

GENRE: HORROR COMEDY

LOGLINE: A 16-year-old neighborhood outcast must save his only ally, an anxious 7-year-old girl, from the supernatural entity, Vitadenghis, whom she has unwittingly summoned with toilet paper.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: This script reflects my fears at the world of today. Come on, headlines are enough to make you shit in your pants. I wanted to take a few of those things, apply some good teenage angst and foible, lots of sexual innuendo, blood and fun and toilet paper. It has heart too, because I have a big heart too. I often receive the largest number of up votes on S.S with small vignettes I write about my life, but those vignettes are often morose, heart tugging things with little room for humor. I wanted to share something that might put a smile on someone’s face here. Let them save the lump in their throat for that special family’s member or their doctor. No lumps in this one, well, maybe at the end, or maybe I’ll be lumped into the scrap pile, but hopefully, someone will soften to it, give it a squeeze.

TITLE: Oakwood

GENRE: Western

LOGLINE: A grizzled alcoholic travels by hook or crook across the Old West to bury his brother but is hunted by those he’s wronged all the way.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: Last time I was here, I was dominated by the Benny Pickles script “Of Glass and Golden Clockwork” and deservedly so. Despite not winning the coveted Friday slot, I was still given a TON of awesome advice on how to better my script (Monty), and was subsequently a Top 10% in the Nicholl Fellowship. Not huge accolades, but for my first screenplay? It felt good! — This is now my third script and I feel like I’ve gotten better since I submitted last. But this is a Western, damn it, and nobody wants them anymore. It truly needs to be the absolute best it can be to get any sort of traction. I really hope that the ScriptShadow community can help me again whether I move beyond AOW or not.

TITLE: Midnight Leather

GENRE: Psychological Thriller / Horror

LOGLINE: After a scandal leaves her hounded by the paparazzi, a grief-stricken actress tries to rebuild her life within the privacy of an isolated mansion that has a secret, and horrifying, past.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: The Scriptshadow 250 Contest sounds AWESOME and I can’t wait to enter! But before I submit this script, I’d love to get it crowd-tested and work in a few more rewrites before the August 1 deadline. Midnight Leather is my sixth script, and it’s been described as psychologically dark, emotionally raw, and having a third act that will linger with you for the rest of the day. The female lead is actress bait for an A-lister looking for her BLACK SWAN, and overall, the script is in the same vein as SHUTTER ISLAND and THE OTHERS.

TITLE: Sugar Daddy

GENRE: Thriller/Drama

LOGLINE: An underachieving medical student gets embroiled in the dangerous world of organ trafficking when she accepts a scholarship sponsored by a conniving businessman.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: I’ve always been a big fan of the May-December romance trope. Whether it’s Jane Eyre, Beauty and the Beast, Last Tango in Paris or My Fair Lady, there’s something that always draws me to the relationship dynamic between an older man and a younger woman. This fascination may even be part of the reason why Fifty Shades of Grey is currently in first place at the box office this week. — So imagine if you could get your hands on a script that contains a lead pair with a similar relationship dynamic and a suspenseful plot set in a cut-throat (literally) and grizzly world where nobody has a moral compass. Imagine a script that’s as sexy as it is intelligent and thought provoking. That is ‘Sugar Daddy’ in a nutshell.

TITLE: INDIANA JONES AND THE STONE OF DESTINY

GENRE: ACTION ADVENTURE

LOGLINE: Memories of an artifact from Indy’s past begin to resurface as the famous archeologist searches for the greatest legend in history, the lost city of Atlantis.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: The Indiana Jones character is at a crossroads. While fans and professionals bicker back and forth on whether or not to reboot the franchise or let Harrison Ford have one more shot, time for one of those scenarios is quickly dwindling. I believe I have written a great script that has just the answer – why not do both? — I attended film school at Columbia College before transferring to USC. I never finished. Instead I started working in the restaurant business, and I now own a catering company for private jets. But I never stopped writing. See what you think.

Get Your Script Reviewed On Scriptshadow!: To submit your script for an Amateur Review, send in a PDF of your script, along with the title, genre, logline, and finally, something interesting about yourself and/or your script that you’d like us to post along with the script if reviewed. Use my submission address please: Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Remember that your script will be posted. If you’re nervous about the effects of a bad review, feel free to use an alias name and/or title. It’s a good idea to resubmit every couple of weeks so your submission stays near the top.

Genre (from writer): Supernatural Dramedy

Premise (from writer): When a delusional drunk retires to the Mexican Border to be left alone, dead desert barflies, a video-game gunslinger and the local drug lord just won’t leave him be.

Why You Should Read (from writer): Everything I’ve written to date has placed at either Nicholl or Austin. This latest effort, I believe, is my best so far, but I write full-time next to the Santa Susanna Nuke plant out in West Hills/Simi Valley. JOHNNY BOOGERS is pretty out there. The percolates, PCE contamination and plutonium migration might be clouding my judgment — I could use some honest opinions, and a new place to live. I would gladly settle for the former.

Writer: Hank Dumont

Details: 103 pages (note: The draft of Johnny Boogers I posted on Amateur Offerings was nine months old. Hank has supplied me with a more current copy).

Wow, yesterday’s exercise was really fun. No doubt we’ll do it again a couple of times before The Scriptshadow 250 deadline. I noticed that some of you were concerned that people were voting for their favorite commenters as opposed to the best idea. But I can safely say that I read every entry and the top two vote-getters, Scott Strybos (reappearance of a dead daughter) and Somersby (Lord of the Flies meets Gilligans Island), had the best ideas.

My personal vote goes to Somersby’s “Jillian’s Island.” There was just something specific about Somersby’s take, whereas a lot of entries relied on generalities. I felt like I read one too many versions of, “A family is lost in a sea of uncertainty as a mysterious energy challenges their beliefs. When they realize the Gods of the Triangle are testing them, it is up to the father to overcome his past to keep his family alive.”

This is actually a good screenwriting lesson as I read lots of loglines with the same problem. They’re all so vague! Phrases like, “a mysterious secret” and “must battle his past,” rarely do anything for the reader. I know loglines are small and therefore must be general in some respects, but often what makes them stick out are the specifics – that’s how you differentiate yourself from the pack.

That’s the perfect segue into today’s AOW winner. I don’t think you can blame Johnny Boogers for being vague or general. The question is, is it too specific? Let’s find out.

“Johnny Boogers” follows Caleb Walcott, a 60 year old gentleman who’s just quit his call center life insurance job and bought a trailer out in the middle of nowhere in New Mexico. The only spot that contains fellow human beings in the area is a dive bar run by a man named Johnny Boogers.

Naturally, Caleb spends most of his time there, getting drunk on warm beer and hitting on the only two women, a couple of Native American lesbians. Retirement is going well except for a local trouble-maker named Cinnamon, who claims Caleb has some heroin of his.

As if that isn’t bad enough, Caleb’s grandson, a retarded kid whose mom was just slammed into by his special needs bus, shows up at his doorstep courtesy of the absentee father. It appears that they’re now going to share custody. Seeing as the child likes to go to the bathroom in his pants, this is seriously cramping Caleb’s retirement style.

When Cinnamon kidnaps his grandson, Caleb must finally make contact with the reclusive Johnny Boogers, who hasn’t made a public appearance in years. Shots are fired. People die. And Caleb will have to rely on the ghosts of the people in the bar, along with his favorite video game character come to life to survive the madness and secure the peaceful retirement he’s always dreamed of.

Well, let’s state the obvious here. You will not mistake Johnny Boogers for being unoriginal. This is a bizarre little screenplay that sometimes hits and sometimes misses. But in the end, like its title, it leaves you a little confused. What is it that I just read? I’m still trying to process that.

One of the more perplexing things about Johnny Boogers was the pace of the story. One of the notes I was going to give was that the story moved too slowly. “You don’t even get to his retirement town until page 30,” I was going to say. But when I went back to check the page number of where that happened, it turns out Caleb got to his new town on page 15!

While I was glad that Hank had moved his story along faster than I thought he did, this leads to a different problem. How come 15 pages felt like 30?

One potential issue was the writing. I found myself re-reading a lot of sentences. Obviously, if you’re reading everything twice, it’s going to take twice as long to get through the story. But I think there’s a good argument to be made that there’s some serious overwriting going on here.

Take a couple of sentences from the screenplay…

“Juvenile Javelina string squirts across the blacktop beneath a Luna County Hwy 9 sign. Insects make their presence known.”

And then…

“Quarter mile out, all four lock up again. Hard left, lights on, the truck crawls down through the ditch, seesaws north and farts tailpipe flames.”

I had to read the first sentence three times to have a semblance of what it meant. And I’m still not entirely sure. And while I understood everything about the second sentence, it seemed an out-of-the-way way to say that a car was going somewhere. Sometimes it’s okay to say: “The car plows through the desert.”

Look, I understand that you’re trying to convey a visual to the reader, and being specific helps that. But there’s a difference between specific and overwritten. And Johnny Boogers walks that line throughout, making for a harder-than-usual read.

For comparison’s sake, here’s an average line from Fargo, a film I would argue is in the same cinematic universe as Johnny Boogers…

“Jerry is sitting in his glassed-in salesman’s cubicle just off the showroom floor. On the other side of his desk sit an irate customer and his wife.”

Look at how simple that paragraph is. Nobody gets to the end of it and goes, “Huh?”

I also scrolled through the entirety of the Fargo script and noticed just how little description there was. When I went and did the same for Johnny Boogers, I saw an immense amount of description, and all of a sudden it became clear to me why it took so long to read. Was all that description really necessary?

Even the dialogue bore the marks of overwriting at times. Lines like, “If it sounds like a baby rattle, looks like an itty bitty lobster, or reminds you of Howdy Doody… it ain’t your friend,” look good on paper until you realize they make no sense.

I’m struggling here because I didn’t read the script under ideal circumstances (I was really tired). But rarely do readers read scripts under ideal circumstances. In fact, with amateur scripts (scripts that their company doesn’t already have an investment in), you’re usually catching readers at their worst time. So it’s your job to pull them OUT of that funk. Not send them deeper into it.

This was a tough review because Hank definitely has talent. But I think he’s trying too hard. Stop trying to write every sentence perfectly and just tell a fun story. Read all of the Coen Brothers’ scripts. They’re masters at creating unique worlds in very minimalistic ways. I wish Hank luck and hope his next one kicks ass. This wasn’t for me though.

Script link: Johnny Boogers

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Don’t let your writing get in the way of your story. The default approach for description should be minimalism. Sometimes an element will be so important that you have no choice but to describe it in intense detail. But when that’s not the case, try to describe the action in the simplest terms possible. There will be times, such as when you’re trying to create mood/tone, where you will take more liberties with your description (February). But I’ve found that only the best writers get away with this and that writing a script that’s description-heavy is almost always a losing endeavor.

Today I’d like to discuss an often overlooked aspect of screenwriting – the angle. The “angle” one tells his/her story from is often what separates the pros from the amateurs. You see, coming up with an idea is only half the battle. Once you’ve done that, you need to figure out the way you’re going to tell that idea. This is the “angle.” And it can turn a boring idea into something extraordinary.

This hit me like a bolt of lightning recently when I caught the new Showtime show, “The Affair.” Now let me ask you a question. Take a look at the poster above. Between that and the title, what are you imagining this show to be like? If you’re anything like me, you probably imagined a straight-forward soap-opera like story about a man who’s bored with marriage who engages in an affair.

And if you’re anything like me, you probably said, “That sounds boring as hell.” It’s not to say that it can’t be good. Maybe they execute the shit out of that idea and it turns out solid. But here’s how I see it. If the premise of your show/movie is something that is often the subplot of other shows/movies, it’s probably not a very strong idea.

And then I watched the show.

And I was blown away.

The genius of this show is the ANGLE. Here’s how it works. We meet a family man, Noah, with four kids and a wife he met in college. The family heads up to their beach summer home, and it’s there where Noah runs into local waitress, Alison. Alison is also married, but, as we’ll find out later, having problems in her marriage due to the loss of their child.

So far, so boring, right?

Except the first half of the show is from Noah’s point of view and the second half is from Alison’s point of view. The show had me hooked after a particular scene late in the pilot. We’d already seen this scene once from Noah’s point of view. In it, Noah comforts Alison after she’s shaken up from his daughter choking. In that scene, Noah is wearing slouchy shorts, a lazy wrinkled shirt, and he looks every bit the role of the overworked parent. In other words, his view of himself. He’s also very bumbling when he speaks to Alison, a woman he’s obviously a little attracted to. She looks sleek and perfectly put together in the scene, and she always seems to say the perfect thing.

Later, in Alison’s version of events, Noah is now wearing a buttoned up stylish shirt. He looks more tanned, more handsome. She, on the other hand, is the bumbling mess trying to get the right sentence out. Her look is pale, her teeth just a tinge less white, her hair a mess. In other words, how she sees herself. The show, then, is a brilliant study not just of two different points of view of the same events, but in how we see ourselves in this world compared to how others see us.

Yet a third element of the show is a running voice over from both characters recounting the affair to a detective. It appears that someone, at some point, was killed, and the police are looking into it. The details of this affair are helping them piece together what may have happened. This, of course, is why we’re getting both sides of the affair – because each person is telling their version.

This, my friends, is what you refer to as “angle.” An affair is boring. It has been done a billion times before. Sarah Treem found an angle, however, that made it fresh, that made it different.

The power of “angles” first struck me in my interview with Ben Ripley about his amazing screenplay, Source Code. Ben admitted to struggling with the idea, at first, of a train wreck involving time travel. He wrote a number of drafts that started after the train had crashed, with a mysterious government group coming in to use a new technology that allowed them to go back in time to figure out what happened. It was a very straight-forward version of the idea, he conceded.

It wasn’t until fooling around with the idea for awhile that he realized he needed to place the story inside the point of view of one of the passengers on the train. That was the “angle” that turned another boring sci-fi idea into one of the best screenplays of the decade.

What are some other examples of “angle” elevating a screenplay? Well, let’s say eight years ago I pitched you an idea about a group of guys who have a crazy bachelor party in Las Vegas. “It’s going to be awesome!” I claimed. “Think of all the zany wacky adventures that could happen to a group of guys partying in Vegas.” Yet the look on your face conveys one of confusion. “That sounds like the most boring straight-forward idea ever,” your eyes say.

What if I then said, “Well wait, let’s change the angle. What if instead of chronicling the night itself. What if they got so wasted they don’t remember anything from the night before. And in the process, they lost the groom! So the movie takes place the next day, as they try and piece together where they were so they can find the groom and make it back to the wedding in time.” Boom, your face lights up. “Now THAT’S a movie!” This is the same general concept, just told from a different angle.

There was no one more flummoxed by the overspending they were doing on this JJ Abrams pilot called, “Lost,” than Disney head Michael Eisner. “I don’t get it,” he would tell anyone who listened. “They crash on the island. Then what???” Eisner was quick to note that the pilot would be exciting. But wouldn’t the viewers get bored when, by episode 10, they were coming up with the 8th different way to try and find a way home?

Eisner clearly hadn’t read the series bible, which stated the unique angle the show would be explored by. Instead of some traditional, “Try to get off the island” show, each episode would be dedicated to going back in time to explore one of the passenger’s lives before the crash. These backstory reveals would then be woven into the present day island story in a way that brought the two worlds together. This was the “angle” by which Lost became one of the greatest television shows in history.

Now I don’t want to scare you. You shouldn’t try to find some amazing never-before-seen angle for your movie/show every time out. Some stories are best told in a simple straightforward manner. E.T. is a wonderful heartwarming movie. I’m not sure it would’ve benefitted by some wild angle like being told backwards or from the point of view of the alien.

Generally speaking, the more common the subject matter, the more the need for an angle. Without the jumping-around-in-the-relationship aspect of 500 Days of Summer, it’s just a straight-forward story about a couple who wasn’t right for each other.

Also keep in mind that you’re not always going to find the angle right off the bat. Sometimes you have to get into the story and write a few drafts before you realize the story could be better told another way. This is exactly what happened with Source Code. Sadly, a lot of writers will get a few drafts into a script and, even though they know it’s not working, say to themselves, “Well, I’ve already committed to this angle. I might as well play it out.” No. No no no no no no no. Why put more time into something that’s not working? Feel out the angles. Look for one that’s more exciting.

And now for some fun. Let’s see if you learned anything from today’s article. Below, I’m going to give you an idea. In the comments, I want you to pitch your ANGLE for that idea. Whoever comes up with the best angle (in my opinion), I’ll give them an AUTOMATIC BID into the SCRIPTSHADOW 250 CONTEST. Make sure to upvote the angles you like. I’m curious to see the popular consensus winner as well. Good luck!

A family boat trip goes awry when they accidently drift into the Bermuda Triangle.

Feel free to pitch either a movie or a TV show. I’ll announce the winner tomorrow on Amateur Friday. Good luck!

Genre: Crime/Drama

Premise: A female FBI agent is dragged into an undercover operation to take down one of the biggest drug tunnels in Mexico.

About: Actor/writer Taylor Sheridan has just beefed up his resume. He first made waves with the well-received Black List script, “Comancheria,” but seems to have really come-of-age with “Sicario,” which has Prisoners director Denis Villeneuve attached and Emily Blunt in line to star.

Writer: Taylor Sheridan

Details: 105 pages (undated)

Alert alert! Do you have a memorable title for your screenplay?

One of the funny things that happens every once in awhile at Scriptshadow is I’ll be scrolling through my database of scripts to see what I want to review next. I see the title of a script along with the writers, then do a Google search of both to learn more about the project. Sometimes, the first result will be: “REVIEW FROM SCRIPTSHADOW.”

WHAT??? I already reviewed this? I’ll go to the review, read it, and, sure enough, find out I did read and review the script. This may sound like a humorous scenario, but it’s a terrible one if you’re the screenwriter. If someone can’t remember your script from the title, it probably means you have a forgettable title.

The script in question was one I actually reviewed quite recently, called “On Your Door Step.” It was a pretty good script. But obviously, that title doesn’t lend itself to being remembered past a few weeks. In order to be memorable, you should be more specific. Take the recent surprise hit, “John Wick.” That’s a memorable title mainly because it’s highlighting a specific name. Do you know what the original title for that script was? “Scorn.”

Scorn???

Talk about a boring forgettable title. We’ve been hardwired by the studios to give our scripts the most dumbed down titles possible, not realizing that the reason they’re doing this is that the more general the title is, the more demographics it can potentially appeal to. As a writer, you have a very different purpose with your title. You need to stand out. So try a few specific titles on for size with your latest screenplay and see how they fit. It may make a big difference when you enter your script into The Scriptshadow 250 Contest.

Today’s much more memorably titled screenplay, Sicario, focuses on FBI agent, Kate Macy. Kate’s been cleaning up the streets of Phoenix with her partner, Reggie, who’s been trying to get out of the friend zone with her for years. On this particular day, the two stumble into a house for a routine kidnapping only to find dozens of dead Mexican bodies hidden in the walls.

Soon after, Kate is recruited by the mysterious Matt Graves, a guy who looks more like the drunk divorced dad at the end of the Tiki Bar than the Department of Justice agent he is. Matt tells Kate he needs her for the big time, and flies her down to the Mexican border, where he shows her just how terrifying the war has gotten.

Every single Mexican cop is controlled by the cartels, so the days of waltzing into the country and throwing their American weight around are done. These days, they have to be smarter about how they attack. Immediately, Kate senses something is off. Why the hell would they want her for all of this? She specializes in kidnappings, not inter-border war games. But Matt remains tight-lipped.

Kate soon realizes how dangerous her new job is. When she meets a good-looking guy at a bar, it turns out he’s been hired by the cartel she’s watching to assassinate her. Kate’s new status has put her on some “list,” which means going back to her old job is no longer an option. She’s in it whether she wants to be or not.

Eventually, Kate learns that this entire operation is about locating and taking down the cartel’s biggest smuggling tunnel. They do that, Matt promises, and all the drugs back in Phoenix will disappear. For once, he assures her, she has an opportunity to really do something impactful. This would be all well and good if Matt was telling her the whole truth. But it turns out he’s using Kate. For what? You’ll have to read the script to find out.

The wide-release crime-drama has gone the way of the dodo bird. The older folks who used to go to the theater to watch these films would rather stay at home and see what’s on Netflix these days. So how is Sicario getting made? I’ll tell you how. Because this is a sweet-ass script – like a bowl of Captain Crunch doused in chocolate milk. And I wasn’t expecting that at all. Most of the crime-dramas I read are “already seen it all before” boring. I’ll tell you why this one wasn’t.

When I read a script – especially when I read the first ten pages – I have this subconscious filter going on, where I’m looking for anything that’s UNIQUE. It could be a line of dialogue. It could be a line of description. It could be a scene. It could be a character. Whatever. If I read 2 or 3 things that I haven’t seen before before the 10 page mark, that’s usually a good sign.

There were three such moments in the first 10 of Sicario. First, we get this line about a character’s eyes. Now I’ve read every eyes description you can possibly think of. And they’re all usually the same. This is how Sheridan describes one of his characters: “He looks young for 35, but his eyes – seems like they lived for decades before him.” I like that. I haven’t seen that before.

This is followed by the house bust scene where our agents quickly realize that over 3 dozen men have been buried in the house’s walls. I haven’t seen that in a crime-drama before. Later in that same scene, a door is rigged with explosives, killing two men in front of Kate. Afterwards, when she goes home, we get a scene of her showering, carefully pulling off the bits of flesh and bone stuck to her from the explosion. Again, have not seen a scene like that before.

So I was pretty much in immediately.

Sheridan does a number of other things well, too. First, Matt doesn’t tell Kate exactly why she’s been recruited for this mission. This leaves her, and us, in the dark, turning the pages in hopes of finding out the answer. Things would’ve probably been boring if Matt told us exactly what we needed to know right away. One of your jobs as a writer is to hold back information every once in awhile to keep things suspenseful. Never forget that.

Sheridan also does a nice job with Kate’s partner, Reggie. Matt doesn’t want Reggie here. He only comes along because Kate won’t cooperate without him. There’s then a ton of conflict whenever the three are around each other because Matt literally treats Reggie like a 3rd class citizen. He is an ant as far as Matt is concerned. This enrages Reggie, keeping lots of tension in the scenes whenever the three must interact.

Also, Sheridan doesn’t make Kate and Reggie a couple. Amateur Screenwriting Mistakes for $100, Alex? He makes them partners only, with Reggie secretly in love with Kate. Again, this creates more conflict, since we can feel Reggie’s love for Kate throughout the screenplay. As a screenwriter, one of your biggest goals is looking for areas to create conflict between your characters. Sheridan does this really well.

And he’s also a really great scene-writer. The best scenes usually come down to the writer’s use of suspense. Even if nothing I’ve mentioned so far has interested you, you need to read this script (I think it’s on scribd.com? – do a Google search) for the Border Shootout scene. This is a fucking awesome scene. In it, our team is trying to get back into the U.S. at the border, but they are 50 cars back in line. They start to realize that various cars in line are Cartel members who are about to turn them into swiss cheese. And they’re sitting ducks. What happens next is freaking awesome. That scene’s going to rock.

The only reason this script doesn’t get an “Impressive” is because Kate’s not a deep enough character. Everything happening around her is really awesome. But if you strip that away and just look at her, she’s kind of boring. This is a pitfall any writer can fall into with drama. Most of the heroes in these types of stories are reserved. The problem is, if you don’t write “reserved” just right, it can easily come across as boring. I think highlighting at least a character flaw can help this – that way you at least have the character fighting something internally. Unfortunately, I don’t think Kate had anything going on internally.

Still, this is really good writing and a worthy script to add to your reading list.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Awhile back we were talking about leading. By itself, leading helps keep the story moving. But there are ways you can turbocharge it to make it even more powerful. One of those ways is to lead towards something DANGEROUS. Let me explain. You can have a character say to Kate that tomorrow night is the going-away party for the Chief. That’s technically “leading,” because the reader now has another point in the script to get to. But it’s an almost empty lead. I mean, we know something’s coming, but it’s not that important. Check out how Sheridan uses leading. Kate goes into Mexico with the Homeland Security Team knowing that it’s going to be dangerous because the only way back is to go through border control on the highway. It’s mentioned several times that the Border Cops are going to leave a lane open for our team so they can get back into the U.S. quickly. But, of course, we know that that lane isn’t going to be open, and that something bad is going to happen to them while they wait in line. In other words, we’re being led to a dangerous situation instead of happy one. Once you make that promise to the reader that a dangerous situation is coming, I guarantee you they will stick around for it.