Genre: TV Pilot (Drama)

Premise: An “upstairs/downstairs” look at the daily activities that plague one of the most exclusive country clubs in the country.

About: This is a project David O Russell (American Hustle, Silver Linings Playbook) was spearheading with Susannah Grant (Erin Brokovich, Party of Five). Apparently the two went their separate ways over creative differences. But Grant is still pushing forward with it and the show will premier in 2015 on ABC. This is the last draft the two wrote together (for those looking around the net for this file, it goes by the name “ABC – Untitled David O Russell – Susannah Grant Proj”).

Writers: Story by Susannah Grant and David O. Russell – Teleplay by Susannah Grant

Details: January 13, 2014 draft (63 pages)

Maybe the British readers can help me out here. Why is it that this whole “upstairs/downstairs” thing, which is being explored most famously in the show “Downton Abbey, is such an obsession with you? Why do these rich/poor mingling-in-the-same-place explorations fascinate you so much?

I have a British actor friend who moved here and I asked him once why he decided to do so. He said that in the UK, it’s a lot harder to break out of your class. Whatever you’re born into, that’s who you’ll be the rest of your life. Whereas in America, nobody cares about that shit. So he’d much rather take his chances here.

I couldn’t believe what I was hearing. Could it be true? One of the most distinguished nations in the world is still running a class system?? What is this? 1709?

I suppose that this would explain the fascination with these types of stories. If there is a class system still in place, the conflict that arises between the “haves” and the “have nots” is interesting, since the characters are locked into those slots. The question is, does that setup intrigue an American audience who’s never had a class system before? Where it’s not as “risqué” for a staff member to cavort with a club member? Let us discover the answer together.

Members Only focuses on an upscale country club that caters to the “best of the best of the best.” The club was built by and is run by the Holbrooke family. The face of the club, and the de facto manager, is Mickey Holbrooke, a 40 year old beauty married to a hotshot Wall Street tycoon named Randy.

As you’d expect, the second Mickey walks into the club to begin our journey, there’s drama. The club is in huge debt, and it’s forcing the board to get creative. They want to hold a professional golf tournament here but they don’t think the tournament will agree because “we have no black people.” So the first order of business is to go out and find a black family to become members of the club.

Meanwhile, we meet Jesse, a kid from the projects who got this job by the skin of his teeth. He’s a new staffer and has been told that if he even looks at someone the wrong way, he can be fired. So you can imagine the torment he goes through when Mickey’s hot horny 17 year old triplets start a game of who can nail the Jesse first.

In the meantime, we meet TONS of other people. There’s Forty, a Holbrooke who just got out of jail for his 3rd DUI. There’s Ava, the cool as can be “I don’t give a fuck” staffer with a propensity for stealing. There’s Malcolm, the hot widowed husband who every housewife wants to bang. There’s Leslie Holbrooke, whose husband dumped her for, get this, her step-mother – a trophy wife to her alcoholic Senator father.

But the story doesn’t really get good until the midpoint. Two agents from the SEC corner Mickey and inform her that her husband is the biggest financial thief since Bernie Madoff. They’re going to take him down in two days. If Mickey helps them, they may be able to protect Mickey, her daughters, and the club. But if not, all bets are off. The duo kindly hand Mickey their card. If she doesn’t respond in 48 hours, they’re making their move. And just like that, Mickey’s life is turned upside-down.

Members Only may be the most jam-packed pilot I’ve ever read. There were 30 characters in this thing. That’s one character introduced every two pages. On top of that, a TON of shit happens. Thefts, cheating, ménage-et-trois’s, death, embezzlement, a golf tournament, a party, several courtings, racism, sexism. I mean, wow. Grant and Russell need an award just for fitting this much stuff into a script.

And actually, the more I thought about it, the more I realized this “jam it all in” approach would work as a screenwriting exercise. You’re always taught to get through your scenes as quickly as possible, but that’s easier said than done. Well, when you write a pilot (60 pages) with so many characters and so many plotlines, you have NO CHOICE but to write scenes quickly. The average scene here was a page and a half. Having to get in and out of a scene that quickly and still keep it compelling? That’s a skill every screenwriter should have.

For example, in a scene where Mickey must call and convince the tournament sponsor to consider their club for the professional tournament, the scene starts with Mickey already on the phone mid-conversation. That’s how we get through scenes quicker. If you start with all the “Hi, this is Mickey calling from blah blah blah,” and the forthcoming formalities, you’re taking a looooooot longer than you need to. Start us midway through the conversation to cut down time.

The problem with Members Only is that despite its best efforts, you can only maneuver through so much plot when you’re introducing 30 people, and for the first half of the screenplay, while I was admiring the work, I wasn’t fully engaged in the story. And I was wondering why. Then it hit me.

Suspense!

There wasn’t enough of it. Meeting people, meeting people, meeting people, is not suspense. It’s meeting people. I mean, there’s a little bit of suspense in whether they’re going to get the tournament to play at their club, but it’s not enough to hook us for 30 pages.

Suspense can’t be treated like a blanket tool. There are variations in its intensity, and if you’re not going to give us suspense with a high level of intensity, our focus is going to wander. In this case, the Defcon 5 suspense plot point didn’t hit until the midpoint – this is when Mickey’s told that her husband’s embezzled hundreds of millions of dollars.

From this point on, the suspense is VERY high because we’re DYING to see Mickey confront her husband. We have to know what she’s going to say and how he’s going to respond. So anything you write between the beginning of this suspense thread and the conclusion of it is golden. We’re zoned into your story until that line of suspense is over.

And that’s exactly what Grant and Russell did. They drew it all the way out, not even telling us at the end of the episode. Which means we’ll have to tune in next week to find out! Suspense is the cornerstone of any good piece of fiction, but it’s especially important in TV where you’re repeatedly asking your viewers to come back after commercials and come back week after week.

Still, the intensity in which I became attached to the story after that suspenseful plot point makes you wonder: why not start the script with a suspenseful plot point as well? Something big and flashy to keep us riveted through all the character introductions? The more I think about it, the more I believe that every stretch of your screenplay should have a suspense thread going on. At LEAST one.

Members Only is a good teleplay but its success is going to depend on how it’s shot. Will it be shot in that dark serious tone that Downton Abbey is shot in? Or will it be treated like the glossy vapid Revenge? Being that it’s an ABC show, it’ll probably be more like Revenge, which would suck. Now is the time for the networks to start challenging the cable channels with riskier fare. If this show has any shot at lasting, it needs to go darker. I just don’t know if ABC is capable of that.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: “And” is a great place to start in a scene. It means we’re coming in on a character in the middle of a conversation. Which means a shorter scene. Which means you’re only showing the good stuff. During the scene where Mickey is on the phone trying to convince the tournament to play at the club, we come in on this line: “And I’ve been a huge fan of your tournament for ages, so this could be a match made in heaven! Excellent! Yes! See you then.” – “And” is a great place to start. But really, the goal is to start anywhere mid-conversation.

Genre: Drama – Thriller

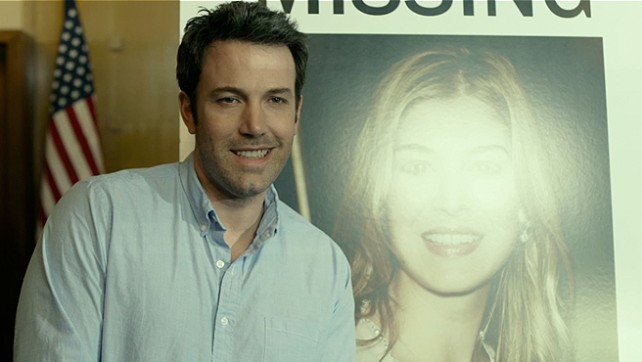

Premise: When a man’s wife goes missing, he finds himself quickly becoming the number 1 suspect.

About: Gone Girl was a hugely popular book that sold millions of copies. The author, Gillian Flynn, sold the rights to 20th Century Fox and, soon after, the great David Fincher came on to direct. It opened this weekend at number 1 (barely holding off horror flick “Annabelle”) with 38 million dollars. Flynn wrote 1000 word blurbs about movies for Entertainment Weekly for 10 years before she found literary success. After reading Gone Girl, which gets into the minutia of a woman wanting her husband to suffer for the rest of his life, Gillian’s husband asked her if they needed to have a talk. Gillian assured him that no, everything she wrote was fiction (yeah right). Believing she had to strip everything out of the book to keep the movie lean, she found that when she gave her first draft to Fincher, he actually wanted to put a bunch of stuff back in. So the script went from lean, to beefing back up again.

Writer: Gillian Flynn

Details: Script (135 pages) Film (149 minutes!)

In a rare move, Gillian Flynn, author of the book, “Gone Girl,” was chosen by the studio to adapt her own work. Usually, this kind of thing doesn’t happen. Novelists are prone to writing from inside the character’s head, going on and on about details, details that work in the context of a novel, but that would cripple a typical screenplay.

For example, whereas a novelist might explain how a character is feeling before she approaches a man, a screenwriter must find a way to convey that feeling visually. So a two page inner monologue where a girl lays out her nerves in exquisite detail probably becomes a simple bobbling and dropping of her phone – a physical way to show nervousness. This is what screenwriters mean when they say, “Show, don’t tell.”

My biggest curiosity going into Gone Girl, however, was how Flynn would handle the ending. In my opinion, the ending of Gone Girl turned what should’ve been one of the best books of our generation into a great big missed opportunity. Would Fincher keep this ending or change it? He had as good of an excuse as any. Movies need to move. We don’t have time for long endings. And there were rumors that he was doing just that. So how would they change it? Would he turn a disaster climax into a classic?? I had to know!

For those who don’t know the plot to Gone Girl, it’s about Nick and Amy, a marriage that looks perfect from the outside, but on the inside is anything but. When Amy goes missing, and there are signs of struggle in Nick and Amy’s house, Nick does what any concerned husband would do. He calls the cops. But early on in the investigation, Nick realizes that he’s becoming the lead suspect. Soon the media catches on, implicating Nick as a classic sociopath killer, and Nick finds himself to be the most hated man in America. Even we start to wonder… did Nick do it?

To appreciate Gone Girl, one must first realize how it’s different. I mean we’ve seen plenty of movies with disappearing women. That’s been done before. So how do you find a new angle?

The primary difference with Gone Girl is that it shows BOTH SIDES of the story. We’re not just in Nick’s shoes. We slip inside the shoes of Amy also. Nick’s half deals with the present, and Amy explains the past. Eventually, Amy catches up to the present, and we keep the back and forth going.

This was brilliant because it upset the typical narrative everyone is used to – the one that’s easy to predict. When you walk out of movies and say, “Ehh, that was okay I guess,” it’s usually because the writer didn’t do anything fresh, give you anything different. This movie thrives off its unique structure, which keeps you guessing.

Flynn’s film is also an argument for the power of twists. There’s lots of little twists and turns here that keep you off balance. Nick secretly has a girlfriend. Amy buys a gun because she’s scared of Nick. And that famous twist at the midpoint where we find out that Amy’s been lying this whole time. Gone Girl really keeps you off guard, and so does a tremendous job of keeping you guessing.

Then there’s the scope of the movie. I’m always fascinated by the question, “What makes an idea a movie idea?” Cause you can’t throw any old idea on the page and call it a movie. It has to be a big enough idea to be “worthy” of spending millions of dollars. Especially these days, when more and more scaled-down films are going straight to Itunes.

So what Flynn did, whether she intended for this to one day be a movie or not, is she increased the scope of the missing woman narrative. Instead of keeping it local, it becomes national. It isn’t just the people in town who are suspicious of Nick. It’s the whole damn nation! That’s what made this big enough to be a movie. How important of a choice was that? David Fincher doesn’t make this movie if it’s contained to a single town.

Regardless of all these positives, everything comes back to that ending. While a lot of people loved the book, one only need go to Amazon and click on the “one star” reviews to see how pissed off people are about the ending.

So did they change it for the film?

Are you ready for the answer? Are you sitting down?

No, they did not. ☹

And it makes what could’ve been a classic film more of a brilliant curiosity.

So what’s the beef? What was so “wrong” about the ending? Well, in the film, the evidence piles up against Nick. Every 15 movie minutes, his situation is twice as worse as it was. It’s really looking bad for him. So we’re really eager to see how he’s going to get out of this, how he’s going to “beat” Amy. Then, just as the American public is about to lynch him…. Amy comes back! Claiming to have been held captive and abused by her crazy ex-boyfriend (which we know, from watching her, is only partly true). And just like that, Nick’s nightmare is over.

Okay, not the ending I was anticipating. But whatever. It is what it is. The End. Right?

Uhhhh, no.

Not even close to the end. We actually stay with Nick and Amy for another 20 minutes, as Amy kinda/sorta bullies Nick into staying with her. She even pretends to be pregnant (or maybe really is pregnant – we don’t know), in order to cajole Nick into sticking around forever.

This ending doesn’t work for two reasons.

The first one is that the film hung around long after the party was over. Since we’re on the topic of parties, I want you to imagine a balloon. Each time you up the ante for your character, you’re puffing up the balloon. Nick is caught cheating with a younger woman. That’s a puff. Nick is caught smiling next to his missing wife’s picture. Another puff. He’s caught taking a selfie with a “fan.” Another puff. He’s forced into hiring a lawyer, making everyone think he’s guilty. Another puff.

The great part about watching a film is watching that balloon get bigger and bigger until we can’t take it anymore! It’s too big! It has to pop! And when it does (i.e. the moment Luke destroys the Death Star), ALL THAT AIR is released. This is why, after the balloon pops, you usually get only one or two more scenes in the movie. There’s no more air left in the balloon, so the audience has no real reason to be there anymore.

The fault of Gone Girl is in popping its balloon (by Amy coming home), and then thinking we’ll want want to stick around for more. Not only are we exhausted from watching that balloon blow up for so long, but no amount of air you can blow into this new balloon is going to equal how big that other balloon got. In storytelling, you always want your story to get bigger (to BUILD). The second it goes backwards and gets smaller, you’ll find yourself an audience that’s losing interest.

On top of this, Amy showing up gets Nick out of trouble without him having to do anything. I HATE that. I think it’s the laziest kind of writing there is – handing your hero the solution. A hero should always have to EARN the solution. That’s why we watch movies, to see the hero solve the problem. I mean imagine if in Silence of the Lambs, Buffalo Bill showed up at Clarice’s desk and said, “I’m sorry for causing all this trouble. I turn myself in.” THAT’S THE EQUIVALENT OF WHAT HAPPENED IN GONE GIRL! Nick is dead in the water and…. HIS WIFE SHOWS UP AND SAVES HIM??? It’s just a really convenient choice and it shows the workings of a writer who gave up, who didn’t work hard enough to come up with something better.

Despite this, I thought Fincher did a great job with what he was given. Even with all that air leaking out of the balloon, he shot those last 20 minutes like a demented backwards fairy tale and made them so uneasy and weird that you kind of went with it. That’s why this guy is at the top of every studio’s directing list. He almost made a terrible story choice work.

And if you take away that ending, the rest of the movie was pretty awesome. Ben Affleck (despite being autistic) was well-suited for the role. Rosamund Pike was appropriately weird and scary. The female cop was good. The sister was good. Maybe the most shocking standout was Tyler Perry, who says that he’d never heard of David Fincher before this film (what???). He was so good as the all-star lawyer, I wish they would’ve found a way to give him more screen time.

So yeah, despite that ending, I still enjoyed Gone Girl. It’s a different take on a familiar subject matter, and it does most of it right. I’m curious though, for those who didn’t read the book, what did you think of the ending? Did you like it? If so, why? I knew it was coming so I was prepared for it but I want to know how it played just as a movie.

[ ] what the hell did I just watch?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the price of admission

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Everyone has their own writing routine. There is no “right” way so don’t feel bad if you’re not doing the same thing as Aaron Sorkin. For example, while a lot of writers will say that you need to be writing all the time, Flynn approaches it a little differently: “I’m a staunch believer in pottering about—I’ve had some of my best writing epiphanies when I’m doing things that have nothing to do with writing. So I may play a round of Ms. Pac-man or Galaga…” There’s nothing quite like sitting down and banging out pages, but for some writers, walking around, procrastinating, thinking of the script in an abstract sense, is the best way to go. As long as your script is in the back of your head, you never know when the next great idea for it will strike.

Read the latest amateur scripts below and vote for the best while offering constructive criticism! Want to receive the scripts in advance? Opt in to get the newsletter!

TITLE: Big Brother

GENRE: Drama

LOGLINE: When a busy executive travels to a small village to investigate his brother’s disappearance, the locals and the atmosphere have an unsettling and lasting effect on him.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: This script made the top 15% in the Nicholl and the second round in the Austin. It is largely free of spelling errors.

TITLE: Blood of the Butcher

GENRE: Crime Thriller

LOGLINE: Diagnosed with terminal leukemia, a corrupt desk-jockey FBI agent enlists the help of an aging hit-man to hunt down the savage serial killer that she let loose.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: After reviewing so many amateur scripts here on Scriptshadow I thought it was time the masses got their opportunity at payback. The script was written as part of the Industry Insider competition, so my only hope is that it upholds the high standard set by previous finalists who have had favourable reviews on SS. Thanks.

TITLE: The Shrike

GENRE: Horror

LOGLINE: A young girl struggles to understand her connection to an ancient monster that impales its victims in the trees.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: Because this is horror with heart. It is also the cleanest, tightest, and most original amateur script of the year. Enjoy.

TITLE: REBEL CITY

GENRE: Crime thriller

LOGLINE: Over the course of one night a reformed father must step back into his murky past to find his criminal brother who is the only suitable donor for his dying son…

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: I think it was Tarantino that said he’d been staring through the window at the industry for so long prior to Reservoir Dogs’ success that it felt normal for him to be on the outside now. At times I very much feel the same. I’ve had the agents, the managers, the lawyers and done the water bottle tour too. I’ve had scripts go out to all the major studios and prod cos and placed highly or won most of the major contests worth entering. I’ve written/directed my own award winning short films that allowed me to go around the world to various festivals and meet audiences first hand, and I’ve had pilots go into networks and yet I’m still here bashing away, whilst staring through that looking glass and working as a bartender. So, I decided to take stock, go away and write something that I’d want to see at the cinema. A movie me and my buddies would find cool. It’s taken me 13 feature scripts and 4 pilots to “find my voice” and I’m keen to show it to a script writing community that’s as passionate about writing great stories as I am. This is REBEL CITY – with echoes of Michael Mann’s Thief and The Friends of Eddie Doyle – it’s a neo noir crime flick… Hope you like it as much as I enjoyed writing it.

TITLE: The Greenhouse

GENRE: Psychological drama

LOGLINE: Seven-year-old Blaire knows nothing of life outside an environmentalist cult led by her mother — but will her grandparents’ fight for custody succeed in time for her to have a chance at a normal childhood?

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: I’m a 22-year-old, recent college graduate with approximately zero screenwriting experience and a devout love for the collaborative environment of this site. My first screenplay, The Greenhouse, was inspired by my relationship with my mother, Ingrid in White Oleander, and a curiosity of the ways subcultures evolve as mainstream culture does. A slightly-less-edited version of this screenplay placed in the top 10% of the Nicholl Fellowships competition, but it’s in need of additional eyes – and opinions on the controversial ending – to help me take it to the next level!

Get Your Script Reviewed On Scriptshadow!: To submit your script for an Amateur Review, send in a PDF of your script, along with the title, genre, logline, and finally, something interesting about yourself and/or your script that you’d like us to post along with the script if reviewed. Use my submission address please: Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Remember that your script will be posted. If you’re nervous about the effects of a bad review, feel free to use an alias name and/or title. It’s a good idea to resubmit every couple of weeks so your submission stays near the top.

Genre: Psychological Thriller

Premise (from writer): A woman who spent her childhood in a cage, is rehabilitated and given the chance to live a normal life when she moves out on her own, but she meets a mysterious man that threatens to undo her progress.

Why You Should Read (from writer): Okey dokey, gonna keep it simple here… I’m a long time reader of SS. I often lurk in the shadows and comment very rarely, but I absorb all the information like a sponge. I’m a HUGE horror fan and also a lover of character driven films. I wanted to do a new-ish spin on the genre, so I’ve come up with this psychological thriller that I think has a good hook and some complex characters. I’m hoping notes from Carson and the SS community will bring the script to the next level.

Writer: Brittany LaMoureux

Details: 93 pages

A month ago, I laid down the gauntlet. I said, readers of Scriptshadow! I implore you to find me a screenplay heretofore unseen by the Scriptshadow Community, yet still worthy of an Amateur Offerings slot! And so you pitched hundreds of scripts in an endless bid to sway my interest, but only one stood out. Everyone seemed to agree that “Pet” was the script to beat. And so review it I will.

Now yesterday we talked about the importance of challenging actors with complex roles so you can get financing-worthy attachments to your project. Pet excels in this area, creating two mentally troubled characters trying to carry on their first ever romantic relationship. So the script’s got the characters going for it. But what about everything else? Time to get your adoption papers in order. We’re not leaving here until we find ourselves a pet.

Mya had the unfortunate distinction of growing up in a cage, courtesy of her psycho mother. When said mother commits suicide, leaving her daughter to rot, her uncle, Jake, comes to her rescue. Horrified by the chain of events, he agrees to raise Mya.

Cut to 12 years later and all that cage stuff is in the past. Mya’s a young woman and wants to get out on her own. Experience the beauties of life. Like standing in the middle of the cereal aisle at 2 in the morning trying to decide between Lucky Charms and Cocoa Krispies. Oh yeah, it’s great being an adult. Jake’s worried about Mya because, well, she’s been sheltered ever since he took her in. To unleash her out into the world now is kind of like dropping a kitten into the middle of New York City.

Mya seems to be doing well though, until she meets Early, a burly intense 30-something who’s a little slow. When Early’s dog gets hit by a car, Mya extends him an olive branch, and all of a sudden they start hanging out. That goes well at first, until Early starts telling Mya that she can’t go to work or contact her uncle. She has to stay here, with him, all the time.

It appears that our little cage-dweller is once-again, a pet. She’ll have to navigate Early’s increasing paranoia and homicidal tendencies if she stands any chance at getting out of this alive. I guess that means if she doesn’t hurry up, it’ll be too late. Heh heh. Get it?

Brittany is a good writer. Pet displays all the qualities of a professional script. The description paragraphs are tight (usually 2 lines or less). There’s a lot of showing instead of telling. The characters are all memorable, even the less important ones (I adored the quirky paint shop owner). The draft is very clean. I don’t think I saw a single spelling/grammar/punctuation error. Which is RARE.

Most tellingly, you see a plan of action here. A lot of times when I read an amateur script, I don’t get the sense that the writer knows where he’s going or what he plans to do. In stark contrast, there’s a deliberate building in Pet, about a girl who escapes from a cage being slowly manipulated into entering another one. We know that the writer knows where she wants to take this.

The sense of dread that permeates the story is reason enough to keep reading, as we know this is going to end badly and are worried for Mya. A good line of suspense can power the majority of a plot. But it can’t operate on its own.

At a certain point, I realized how little was going on in the story. The relationship was developing, and there’s a little side-story about Mya trying to be a better employee at her paint shop. But other than that, we’re just watching Mya and Early get to know each other. And since neither of them talk that much (which I’ll get to in a sec), it wasn’t that interesting.

To address this, I thought we needed a twist or two in that middle section – something that changed things around to freshen the story up. The way Hannibal Lecter is released from his cell in the middle of Silence of the Lambs. Something that stirred up the narrative. I actually thought that Brittany was going to trick us. She’d imply that Early was going to be the psycho one, but then pull the rug out from under us and have Mya be the one who cages Early.

The way it stands now, we have yet another creepy guy potentially killing a woman. Is that an original choice? Can we do better? Now that I think about it, I realize that my need for twists may imply a bigger problem. Maybe the second act is too slow because we’re not approaching it correctly. Maybe Mya needs more to do, more directions she’s being pulled in. More plot!

And about that dialogue. Typically in a script, you’ll have one character who’s the dominant talker, and a second character who’s the secondary talker. These two will take up 60% of the movie’s dialogue or more. In Pet, you have two “secondary” talkers, and that results in a lot of basic, restrained dialogue.

Whenever your main two characters – the people who talk more than anyone else in a script – have similar ways of talking, you get these huge chunks of dialogue with very little contrast. Dialogue where both characters sound the same can be brutal. But if both characters are also introverts and therefore don’t talk much? Now you’ve really handicapped yourself. I mean how are you going to make that kind of dialogue consistently entertaining?

Here’s an exchange from the middle of Pet. “Nobody aint gonna lock me up no more.” “It’s okay.” “You don’t get it.” “Yes. I do.” “I need to paint.” This is a small sample size but it’s reflective of how a LOT of the dialogue reads. And you can see how that might get frustrating after awhile. At least with me, I wanted to pick these two up, shake them, and say, “Say something!! Don’t just mumble four-word sentences. Say what’s on your mind, man!!” But that moment rarely came.

And to be honest, I don’t know the perfect solution to this. If you make Mya like Clementine from Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind (babbling all the time) it wouldn’t fit the mood or the tone of the story. If I’d spotted this in the outline stage, my solution would’ve been to avoid it altogether. Rebuild the story so you’re not stuck in this pothole in the first place. But that doesn’t really help us now, does it.

I guess technically you need to bring a little more personality out of one of the characters. I always start with humor. Every character has their own sense of humor. It’s a little harder to find humor in really serious pieces, but it can be done. And when it’s done right, it can liven that dialogue right up. Look no further than The Skeleton Twins. That dialogue could’ve been really depressing. And it was in places. But they found ways to make it funny too. And I realize Pet isn’t that movie. It’s its own thing. But I really feel like one of these two needs more personality if we’re going to stick with them for 95 minutes.

All in all, Pet was a solid effort from a writer I’ll want to see more of in the future. If I hear a good logline from Brittany, I’ll definitely ask to read the script. But this one moved a little too slow and the characters were just a little too reserved for me.

Script link: Pet

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Early in the script, one of the characters in Pet mentions dating on Craigslist. I’ve been noticing a new trend in screenwriting where writers depend a little too heavily on internet-related activities for their characters. They go on Craigslist or watch porn or jump on Twitter or check videos on Youtube. The more it happens, the more it sounds LESS LIKE a real person’s life, and MORE LIKE the average day of a certain writer who never leaves his computer. Your writing is a reflection of your experiences. But your characters should have their own experiences. And a lot of those will be real-life stuff. Don’t fall back on the internet because it’s easy and what you know.

So today I read the news that Ben Affleck is thinking about making The Accountant his next project. “The Accountant”?? I wondered, my face pinching up, trying to remember why that sounded familiar. Off I went to my review archives and LO AND BEHOLD, I’d reviewed it! But that’s impossible, I thought. I would’ve remembered it, right? Yet I was drawing a size-10 blank.

But once I skimmed through the review, it all came back to me. The awfulness. The sloppiness. I remember actually thinking at one point that I’d been duped. That’s happened a few times, where I hear about a script, go looking for it, find it, it turns out to be unreadable, then I later learn I’ve read an amateur script with the same title.

So then why was Ben Affleck doing the movie??? Take whatever you think of Affleck as an actor out of the equation. The guy is the hottest thing since sliced bread at the moment. Which means he gets all the best scripts in town. He gets his pick of the litter. So for him to literally choose “litter” to star in was confounding.

Until you look deeper. You see, the main character in The Accountant is autistic. And this is the screenwriting secret that so many writers either ignore or are ignorant to. Outside of the summer tentpoles, actors make a movie go. They lead to financing which leads to a green light. Which logically means that to get a movie made, you have to write a great character that an actor will want to play.

In fact, for 90% of the actors out there, the role they play is more important to them than the script itself. They want to play a part that’s challenging, that’s interesting, that’s going to get them some acting credit. When you look at it that way, it’s not so ridiculous that Affleck would choose this script. He wants to play an autistic hitman. He’ll either fix the rest of the script himself or hire Chris Terrio to do it. But dammit if he’s not going to play that autistic hitman.

This brought me to a realization that I’ve already had several times before, but for whatever reason, didn’t become crystal clear until today’s events. Unless you’re writing a huge summer flick, you need to put more emphasis on the character at the center of your story than the story itself. Cause that’s what the actors are going to do.

Which leads us to today’s article. I’m listing the top 17 “challenging” character-types that actors want to play. If you can fit these into your story in a natural way, you’ll want to consider it. ‘Cause I guarantee you this: If your main character is bland, no A-list actor is going to make your movie.

Autism – Why not start with Affleck’s new love? The disorder did wonders for Dustin Hoffman with his role in Rain Man. Because acting is, in many ways, about emoting, there’s something appealing about a character who does the complete opposite.

Psychopathic – Being a psychopath isn’t just about murdering. It’s about playing anti-social and non-empathetic behavior. Its appeal is that it’s another condition that goes against how we normally act in life. Inevitably, these characters tend to become killers (American Psycho, Monster, Taxi Driver) but it’s all the other tics that get the actors excited.

Going Crazy – Aw man, talk about actor catnip. Write in a character who’s going nuts and watch the A-listers line up, as “going crazy” often leads to an Oscar nomination. A Beautiful Mind, The Aviator, The Shining. These characters are fun to write as well, so it’s an actor-writer match made in heaven.

Robots – Bringing sci-fi into a venue where we’re looking for meaty rolls seems counter-intuitive. But much like playing a psychopath or a sociopath (the psychopath’s little cousin), playing a robot forces you to strip away all your emotions, a challenging feat. We’ve seen great robot characters in the Alien movies, as well as 2001.

The Genius Paradox – Talk about the perfect part to play to actors’ egos! A genius character! We saw it recently with Lucy. Before that, Limitless. As we saw in my recent review, “Brilliance” will be coming to the big screen soon. Thrusting genius into your lead character is a surefire way to get some actor attention.

OCD – OCD got Jack Nicholson one of his Oscars (in As Good As It Gets). We just saw it to a lesser degree with Robert McCall in The Equalizer. They even based an entire show around OCD once (Monk).

Addicts – Many actors have demons. And playing addicted characters allows them to explore and battle those demons, if only for a few months. From Flight to Leaving Las Vegas to Half-Nelson, playing a convincing addict seems to be a badge of honor for actors.

Mentally Challenged – This has been made fun of plenty of times before, most notably in “Tropic Thunder,” but what can you say? Actors love the challenge of playing someone who’s mentally challenged. Forrest Gump. I Am Sam. I mean, if you can pull this off, you’re basically guaranteed an Oscar.

Twins – Imagine you’re an actor and you get the opportunity to play not just one role in a movie, but two? Two completely different characters. What actor isn’t going to take that into consideration? Check out The Prestige or The Social Network to see this in action.

Body-Swappers – Looked down upon by some for being gimmicky, a body swapping movie allows actors to play two roles which are usually polar opposites. We saw it with Face-Off. We saw it in The Change-Up. But don’t limit yourself. I think it’s only a matter of a time before someone comes up with a clever body-swapping drama idea.

Amnesia – Amnesia gets a bad rap for being cliché, but don’t tell actors that. They love playing people who can’t remember jack shit about who they are. That’s a hell of a challenge. Bourne built an entire franchise off this conceit.

Pathological Liars – A character whose every day survival depends on lying can be fascinating for an actor to play (and for an audience to watch!). We saw William Macy do it in Fargo, and Hayden Christensen nail it in Shattered Glass.

Self-destructive – This is usually tied in with addiction, but can exist on its own as well. Some of the most tragic characters in our history did themselves in due to being self-destructive. Most recently, we watched this play out in Wolf of Wall Street.

Depression – Depression is sad. But it sure makes actors happy. Punch Drunk Love, Revolutionary Road, Silver Linings Playbook, Little Miss Sunshine. It’s a clever way to lure in comedy actors hoping to play against type (Skeleton Twins).

Any extreme limitation (blindness, wheelchair-bound, deaf, cancer) – The Book of Eli. Sea of Love. Born on the Fourth of July. The Fault In Our Stars. Dallas Buyers Club. It goes without saying that actors love to play these roles where they’ve been handed an impossible limitation.

Discriminated Against – One of the greatest 1-2 punches for drama is to set a movie in a time where a subset of people are being heavily discriminated against, then make your main character one of those people. A black man in the 1960s. A gay man in the 1950s. A Jewish man in Germany in the 1940s. You’ll have to fight actors off from taking these roles.

Get creative – Look for any way to create a challenging lead role in your script. Benjamin Button got made because Brad Pitt got to play every age in life, from a newborn to an old man. In the Black List script, What Happened to Monday, an actor will get to play septuplets! I seem to remember a movie awhile back that centered around a Jewish Nazi. Create something that, at its core, is challenging. These are the roles actors are drawn to.

Now there are a couple of caveats to this business. The character you’re writing has to fit into the story you’re telling. A meth-addict protagonist may increase interest from actors, but it’s not going to work if you’re writing a romantic comedy produced by Mark Burnett. In other words, don’t slap a fancy character into any old idea and expect miracles. The two must co-exist organically.

Also, none of these suggestions will work unless you convey them in a truthful manner. In other words, research the shit out of them so that you know what you’re talking about. If you try to write an autistic lead and all you know about autism is what you’ve seen in movies, I guarantee you the character’s going to suck. Do tons of research and find out what everyday life is like for these people. The more you know, the more convincing they’ll be, the more likely an actor will be attracted to them.

And, as always, take these suggestions as a starting point. They won’t work on their own. They need your own personal spin to pop. A great way to do this is through irony. Make a sex addict the new church pastor. Make your protag, who suffers from depression, a Barney-like character on a new kid’s show. I hope that helps.

What do you guys think? Anything I should add to the list?