Genre: Thriller

Premise: A psychiatrist tasked with determining if death row inmates are mentally fit for execution encounters a strange inmate who somehow knows everything about her.

About: This appears to be one of those scripts that slipped through the awareness cracks. It did finish on the Black List last year, but near the bottom. The script sold to Lionsgate in a bidding war, and ended up with a mid-six figures price tag. The writer, Hernany Perla, had been working at Lionsgate as an exec.

Writer: Hernany Perla

Details: 111 pages

Michael Fassbender for Samuel?

Michael Fassbender for Samuel?

Now I know what a lot of you who read the “About” section are thinking. “OF COURSE HE SOLD THE SCRIPT! HE WORKED AT THE PLACE THAT BOUGHT IT!” Oh, if it were only that easy. Because only EVERYBODY in Hollywood, whether they work at a production house, a studio, an agency, or a management company, has a script they’re hawking. And while the sell rate is definitely better if you’re inside the system, I’m betting the odds are still pretty low. I’m guessing less than 1% of those working at studios sell their scripts.

The way I see it, there are two types of writers, no matter where those writers reside. Casual ones and serious ones. The casual writers think if they write ANY-thing, success will come. The serious writers do the work. They read, they study, and they write their asses off. I don’t know Hernany Perla, but judging by the quality of this screenplay? I can make a strong argument that he’s one of the latter.

The REAL advantage of working as an executive, and why these guys have a leg up on the competition, is because they read a lot of scripts. That’s their job. But it’s not just that. They’re tasked with figuring out what’s not working, then coming up with solutions to improve the script. That trouble-shooting muscle comes in handy when one’s writing own scripts.

“Revelations” follows Dr. Kayla “Kay” Margolis, a successful psychiatrist who’s been assigned to Death Row to decide if the current crop of inmates are mentally fit for execution. Of course, when these guys are facing down death and they know their only out is to plead insanity, they all try and plead insanity. Kay’s job is to cut through the bullshit.

Then Kay meets Samuel Desmet. Shaved head, looks like one of those hare krishna guys. Which is apropos, since he once led his own cult. Samuel’s on Death Row because he blew up a group of people.

Kay’s a little thrown by Samuel’s Hannibal Lecter-like charm, but she seems to have the situation under control. That is until Samuel mentions Kay’s boyfriend, Troy. There is no possible way that Samuel could’ve known Troy, and it freaks Kay the fuck out.

But that’s just the beginning. According to Samuel, he (Samuel), is a God, being reincarnated over and over again. He’s had this conversation with Kay a countless number of times already. And he needs her on his side if they’re going to stop what’s coming. “What’s coming?” Kay wants to know. “Winter.” He says with a whisper. Just kidding. He says the current Governor, who’s also a reincarnated God, is going to set in motion a series of events that will result in nuclear war. And Samuel’s the only one who can stop him.

Kay knows this is bullshit, but over the course of the next few days, Samuel keeps telling her things that he can’t possibly know. He even sends her to a library to check out a book that was written 100 years ago. It was a book HE wrote in a previous life for this very moment, to prove to her he’s real. In it, there’s a direct message to Kay. That she can no longer trust her boyfriend Troy, who’s cheating on her.

You’d think that would be enough evidence, but there’s always one thing that puts every proclamation of Sameul’s in question. With a little digging, for example, Kay finds out this 100 year old book was placed in the library a day ago. When she questions Samuel about this, he swears it’s Governor Cayman, who’s making him look like a liar so she won’t help him.

Kay only has a few more days left to figure it out, because at the end of the week, he’ll be executed. If she saves him, is she just another victim of a persuasive cult leader? Or could it be that she truly is saving humanity?

Ever since I read that Lee Child article, I’ve been obsessed with suspense. How a story’s success boils down to setting up questions and then stringing the audience along until those questions are answered. That’s pretty much “Revelations” in a nutshell. And it’s very effective. Samuel makes a statement that something’s going to happen in a few days (i.e. a security breach at a nuclear facility) And we furiously read on to see if, indeed, the event happens.

Even better, Hernany LAYERS these suspense plotlines so we always have more than one thing to look forward to. For example, Samuel says that Kay’s boyfriend can’t be trusted. He says that there’s going to be a book he wrote 100 years ago in the library. And he says there’s going to be that security breach, all before any of these answers come yet. It’s kind of like story crack. One suspenseful storyline is good. Three is great!

Another thing I liked here was that Hernany didn’t JUST rely on plot. That can happen when you write thrillers, especially thrillers like this. Everything’s about the twists and the turns and the suspense, and you can get so wrapped up in that that you forget you’re dealing with actual people here. No matter how Hollywood you’re getting with your script, you can never totally ignore character.

That’s why one of my favorite threads in the script was the cheating stuff. Once Samuel tells Kay that Troy is cheating on her, everything about their relationship is uncertain. When she comes home, she’s watching Troy closer. When he’s on the phone, she’s asking who he’s talking to. When they go to work functions and he talks to a woman, she’s wondering, “Could that be the one?” It added another dynamic to the story besides the ‘end of the world’ plot.

There was only one thing wrong with the script. When you started to scrutinize it, I’m not sure it all made sense. At first, Samuel wants to die, because he’ll be reincarnated more quickly than if he lives out the rest of his years in an institution. And once he’s reincarnated, he can try to stop Governor Cayman (another “God” who’s lived hundreds of lives). But if that’s the case, why is he saying all this gobbledy gook to Kay, making her think he’s crazy, if that’ll prevent the state from executing him?

Then later in the script, when it’s looking like he’ll escape death due to insanity, he goes to Kay and says he’s been conning her. Nothing he’s said to her has been true. This, she presumes, is to ensure the state kills him. So he can be reincarnated. That left me wondering, “Why the big show? Why not claim you’re a fraud right from the start if you want to be executed?” It just didn’t add up.

Usually, faulty logic like that will kill a script for me, but I was so insanely caught up in whether Samuel was telling the truth or not that I didn’t care. The genius of this script is you’re unsure about Samuel right up until the end. And that mystery dug its claws into me and never let go.

But the biggest reason I liked this script was that it was so damn FUN! It’s been awhile since I’ve had this much fun reading a script. There isn’t a slow page in the screenplay. Every single scene moves. It’s just good writing. This should’ve finished a lot higher on the Black List.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Never answer a question right away in a script. Every question is an opportunity to draw the answer out (for suspense). You can draw out the answer for 10 seconds. You can draw it out until the end of the script. It’s up to you. But you definitely want to draw it out.

What I learned 2: Layering suspense – Don’t just lay down one suspense thread. Layer them on top of each other so there’s always two or three unanswered questions going on at once.

Genre: Drama

Premise: A family who owns an upscale hotel in the Florida Keys sees their world turned upside-down with the re-emergence of their oldest son, the Black Sheep of the family.

About: We got another Netflix series here, this one from Damages creators Todd A. Kessler, Daniel Zelman, and Glenn Kessler. I never watched Damages cause it wasn’t my type of show. But I repeatedly heard about how well-written it was, which is why I decided to check this out. The show will star Friday Night Lights’ Kyle Chandler, as well as Chloe Sevigny and Steven Pasquale. The creators (Glenn and Todd are brothers) reportedly worked for an entire year on their pitch, which Netflix ate up. The Kessler brothers attended Harvard as well as went to film school at NYU. Not a bad pedigree.

Writers: Todd A. Kessler, Daniel Zelman, and Glenn Kessler

Details: 88 pages – First Writer’s Draft – 11/14/13

Kyle Chandler will star, presumably as Sheriff John Rayburn

Kyle Chandler will star, presumably as Sheriff John Rayburn

Here’s the problem when a business sector starts thriving. Everyone rushes into it. The excitement accompanied by this rush has the unintended effect of loosening quality control. Everyone figures there’s so much good going on, why stop it? Look no further than the boom of Reality TV. Do you remember when all you had to do to get a reality TV show was show up with a half-baked idea? Joe Millionaire! Who Wants to Marry a Millionaire? My Big Fat Obnoxious Fiance!

Okay, okay. So that’s not that far from where we are now. But you have to remember that back then there was one-tenth the number of outlets for those shows. Finally, someone realized, “Hey wait a minute. We need some quality control!”

I think there’s a little of that going on with the TV boom right now. People are so excited that TV is doing well that they’re getting kinda lazy. Take WGN’s Manhattan. What’s the point of this show??? We’re gonna diddle around with a bunch of science nerds until they blow up Japan? Do we really need 7 seasons of television to tell that story? I don’t think we do. But people are so eager to fill up these original TV slots that they say, hell, why not??

I bring this up because despite the glut of shows hitting the airwaves, we haven’t had a true breakout show in awhile. True Detective maybe? But that was more of a mini-series. The Blacklist? Ehhh… I feel like the only people who watch that are James Spader’s family. I’m wondering if that’s a result of this lack of quality control, or if we’ve just reached a point where there are more TV slots than there are good writers. Granted, I’ve read some good TV scripts this year. But writing a good TV script isn’t the same as making a good TV show. The only thing you have to go on is, have they done it before? And today’s writers have.

The Rayburn family pretty much owns one of the islands in the Florida Keys. They have a thriving upscale hotel business that has made them rich beyond their wildest dreams. Each member of the family has something good going for them. There’s John, who’s the town sheriff. There’s Kevin, who has a thriving business fixing boats. There’s Meg, who helps manage the hotel, and then there’s mom and dad, who own it. Each of them are beyond content with their lives.

And then there’s Danny. The black sheep. He’s the sibling who never follows through on his commitments. Who only shows up when he needs money. Who hangs out with the sketchy crew. And who always screws up even the most minor situations.

So when The Rayburn family has their annual Family/Hotel weekend-long party-thing, guess who’s the last one to show up (if you guess John you are a bad reader). Although I can’t say I blame Danny. The Rayburns idea of fun is holding family swimming contests and taking the canoe out for a morning paddle.

Things start to unravel at the ball-sized dinner when Danny purposefully shows up with a cheap townie in order to cause a scene. It’s revealed that Meg, meanwhile, is cheating on her boyfriend. And John is pulled away from the party where he learns that a second woman this month has been burned and drowned, this right before the big tourist season.

As is the case with all seemingly perfect families, we get the sense that this one isn’t as beautiful underneath as it is above. And this will play out in the worst way, when the family collectively makes the decision to do something unfathomable, something so terrible, that it will change their family…forever.

Chloe Sevigny will likely play sister, Meg.

Chloe Sevigny will likely play sister, Meg.

I’m going to be honest here. One of the reasons I never watched Damages was because it looked like it was written by… hmm, how do I say this? By entitled well-off, got-all-the-breaks in life Ivy League folk who write for like-minded people. It kind of had that “You’re not invited to the adult table” exclusivity feel to it. It just looked so serious and smart.

Now I admit I don’t know if it actually played that way, but the first half of KZK definitely backs this assumption up. You can feel the writers’ pedigree slithering up the page. I felt at times like I was Mark Zuckerberg in The Social Network, sneaking into a Final Club where I didn’t belong. I mean where in life do people really worry about things like what table they’re assigned to for dinner. It’s dinner. Bring out the food and let’s eat!

For that reason, I couldn’t relate to any of these characters, which made it hard to care about anyone. Ironically, the only character I related to on any level was Danny, because he looked down on this elaborate lifestyle. The problem was, Danny was such an asshole that I still couldn’t root for the guy.

Luckily, as the script went on, it started to feel more like a story, particularly when the dead burned woman showed up. But it was really Danny who kept this pilot afloat. He was our only source of conflict. It was like dropping a piranha into a pool of goldfish. Everywhere he goes, he makes people uncomfortable, he changes the direction of the moment. Which was exciting to read.

A perfect example is the big dinner. Danny shows up at the table with some half-wit waitress from town and just lets her drink as much as possible. The family, who’s supposed to appear perfect to the crowd, now has this townie-bomb slurping up every apple-tini in sight, preparing to do who knows what to embarrass the hell out of them. And that certainly kept me reading.

I will put my foot down and say there’s a device I’m seeing a lot of in pilot writing that I don’t like. And I saw it here too. The writer writes a big flash-forward teaser, one that implies something bad will happen later, and then skates by the next 30 pages on the assumption that this has generated enough suspense that they can use those pages to set up characters in the most boring way possible.

The 30 pages after our teaser amount to people preparing for the party. The sequence was obviously inspired by 70s movies like The Godfather and The Deer Hunter, but (and I know this will drive Grendl crazy to hear) audiences don’t have the patience for that stuff anymore. Not unless you’re packing some plot into those pages, giving us other things to look forward to. If you go ten minutes without something happening, your viewer is checking their e-mail.

Now in an interview with the writers (something I went searching for when nothing happened for ten pages), they said this was going to be a show that no one had ever done before on TV. So I was looking for any elements to back this claim up. I could only find one. Danny keeps encountering some woman that he’s both terrified and intrigued by. She seems to show up and disappear at the oddest moments, and we begin to suspect (or at least I did) that she may have been someone Danny killed in the past. It was weird and definitely peaked my curiosity.

But then something beyond unexpected happened that made this development moot. And I’m going to get into major spoiler territory here so you might want to turn away. Here was this Danny guy – the only interesting thing about this pilot – some might say the key to this pilot working, and then at the end, the family fucking kills him! I read it three times to make sure I read it correctly. But yes, they actually kill off the best character in the script.

Now there are a couple of hints here that this could be one of those flashback-type shows. Where we’re jumping forward and backward in time a lot. Which means Danny may not be entirely gone. But I thought that was a pretty bold move from the writers, and it turned what was a slightly above average pilot into something ballsier. I like when shows show balls. In a world where so many writers stick on 17, it’s the guys that say “hit me” that win the big pot.

I remember the Game of Thrones pilot script doing something similar. After spending its first 60 pages doing nothing but setting up an endless list of characters, it wowed us with the incest/push the kid off the tower ending. So maybe this should be a new trend. The kill or maim a main character at the end of your pilot move?

I don’t know. But with the pedigree of these writers and the reports of how much Netflix loved this pitch, there should be a big push behind it. It’ll be interesting to see where it goes.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Drop a piranha into the pool. Instead of having to pull your pick axe out every time you want to dig for conflict, just create a “piranha” character, someone who IS conflict. Therefore, every scene you drop them into, the conflict writes itself. Danny was that character here.

Genre: Drama

Premise: When 30-something Milo tries to commit suicide, his estranged sister, Maggie, invites him into her home, where the two start the process of healing old wounds.

About: Writer/director Craig Johnson graduated from NYU film school a decade ago, where he originally conceived of this idea with fellow student Mark Heyman (who wrote Black Swan). The two eventually went their separate ways, coming back to the script only recently, where they re-focused it on its best asset, the brother-sister relationship. Johnson has one other movie under his belt, the little seen True Adolescents, which starred Mark Duplass. He’d been trying to get Skeleton Twins made for awhile with different packages, but it wasn’t until Kristin Wiig came on that he finally believed the movie would get made. And it did!

Writers: Mark Heyman and Craig Johnson

Details: 93 minute runtime

I actually saw two movies this weekend. The Skeleton Twins and The Maze Runner. For The Maze Runner, I tried to bring a little of that “opening day enthusiasm” typically reserved for movies like The Avengers and Star Wars. So I lugged in a big block of cheese. ‘Cause it was a maze? Like rats in a maze? The theater ushers didn’t understand the joke and told me I either needed to eat the cheese, throw it away, or not see the movie. I sighed and threw it away.

The cheese turned out to be relevant in a different way in that most of Maze Runner was cheesy as hell. Even worse, it employed the classic screenwriting mistake of making the main character ask 60 million questions: “What is this place?” “Where are those guys going?” “What happens in there?” “What’s a runner?” “What’s that noise?” “What happens if they don’t come back?” “What’s a Griever?” Word to the wise – if your main character is always asking questions, he doesn’t have any time to, actually, you know, do stuff.

The movie really wasn’t that bad. It was just generic. I hate giving that note to writers cause it sounds so vague but it’s so often the problem. Every choice feels like the first choice the writer came up with. A maze that changes. Seen it before. Spiders inside the maze? That must’ve taken a while to come up with. The lovable underdog fat kid. Oh, and let’s not forget the dialogue (Mopey character who thinks he’s going to die: “Take this [trinket] and give it to my parents when you get out of here.” Hero gives the trinket back to mopey character. “No. You’re going to give it to them yourself.”).

But the biggest faux pas is something you just can’t screw up as a screenwriter. You have to give them the promise of the premise. If you’re writing a script about a giant maze, that maze better be fucking a-maze-ing. And this one wasn’t. It basically amounted to tall ivy-covered walls with giant spiders running around in them. That’s it?? Your maze boils down to Wrigley Field meets Harry Potter?

Lucky for me, I also got my suicide on this weekend. But before I get to Skeleton Twins, I have to do some name-dropping. It was Friday night at the Arclight in Hollywood. As Miss Scriptshadow and I were heading to our theater we saw none other than KEVIN SMITH barge through the lobby (he was moving like a cannonball). I remembered that his movie Tusk was opening and figured he was going to watch his own movie. Which is kind of strange but also kind of cool at the same time.

The funniest part was as he walked through, every single person turned (around 100) and whispered, “That’s Kevin Smith. Hey, that’s Kevin Smith. That’s Kevin Smith.” I guess if there’s one place Kevin Smith is going to be a mega-celebrity, it would be at a cinema-loving theater like Arclight in Hollywood.

Anyway, we rode that excitement wave right into our suicide film, which I was only seeing because it got such a high score on Rotten Tomatoes (I’ll see anything above 90%). Usually I despise films like this. Depressed indie people being depressed, trying to commit suicide, then being more depressed. Count me out. But lo and behold, this ended up being one of my favorite films of the year!

30-something siblings Maggie and Milo haven’t seen each other for ten years. Coincidentally, on the exact same day, they both try to commit suicide. Maggie gets the call about Milo being at the hospital before she can off herself, so she goes there and asks Milo to come live with her and her husband, man-child but sincerely lovable Lance, until he feels better.

Over the next few weeks, Milo, who’s gay, reconnects with an older man whom we find out was his teacher in high school. In the meantime, we find out that Maggie, who’s trying to have a baby with Lance, is secretly taking birth control so she doesn’t have a child. She’s also banging her scuba instructor, which I guess makes the birth control a “kill two birds with one stone” type of deal.

We eventually learn that the siblings’ self-destructive ways stem from their own father jumping off a bridge when they were just kids. It seems, for all intents and purposes, that they’re just following the script, doing what daddy did. So the question becomes, can they put the past behind them and move forward? Or are they on a collision course with fate, one they have no control over?

First I lauded a script about two cancer-stricken teenagers earlier this year. Now I’m touting suicide entertainment. What’s wrong with me???

Not only was The Skeleton Twins good, but it succeeded where many other an indie film have failed. You see, when you don’t have a clear plot (like The Maze Runner – “Get out of the maze”), the story can easily get away from you. Without that big plot-centric protagonist goal, it’s not always clear where you’re supposed to take the story.

Well, in character-driven screenplays, like this one, the point shifts from achieving a goal to resolving relationships. That’s it. That is what’s going to drive the reader’s interest or not drive it. You create 3-5 unresolved relationships – characters with a big problem between them – and then you use your story to explore those problems. If the problems are interesting and you explore them in an interesting way, we’ll stick around to see what happens. Here are the four main relationships in The Skeleton Twins…

1) Maggie and Lance – she’s not sure if she wants to be with him.

2) Maggie and her scuba instructor – she’s trying to end the affair but can’t.

3) Milo and the old high school instructor – their relationship was cut off when they started it in high school. They have to figure out where it is now.

4) Milo and Maggie – they still have a few things from the past to resolve.

The other big thing you want to do with these non-plot-heavy indie movies is throw a lot of plot points at the story. Remember, we don’t have that big goal at the end to drive the film (Win the Hunger Games!), so you have to, sort of, distract us from that.

The Skeleton Twins does a great job of this. Maggie and Milo’s mom (whom they both hate) shows up unexpectedly. We find out Maggie’s hiding birth control. Maggie has an affair. We find out Milo had a relationship with his high school teacher. Lance finds out Maggie’s been on birth control this whole time they’ve been trying for a baby. Maggie ironically forgets to take the pill, discovers she’s late for that time of the month. I mean, for a tiny indie movie, there’s a lot of shit happening here. And that’s the way you have to do it with these indies.

I think lots of writers believe that because it’s an “indie” they need to show 20 minute shots of characters forlornly looking out at the sunrise set to an 8 minute Iron and Wine song set on repeat. There are a few of those shots in here, for sure. But the reason The Skeleton Twins succeeds where all these other indies fail is because it really packs a lot of plotting into its 90 page run time. There’s never something not happening.

On the non-screenwriting front, it was genius to cast comedians in these roles. This movie would’ve crumbled under the weight of two dramatic actors playing ultra-dramatic roles. The reason the film never falls too far into depression-ville is because of the dry offbeat humor Wiig and Hader keep slipping into their performances. Even Luke Wilson was great as the husband. Both funny and sympathetic.

This was a hell of good film. I should’ve saved my block of cheese for it.

THE MAZE RUNNER

[ ] what the hell did I just watch?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the price of admission

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

SKELETON TWINS

[ ] what the hell did I just watch?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the price of admission

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Small indie movies need a lot of PLOT POINTS. You need to keep throwing things at the characters or revealing secrets to keep the story moving and alive. Go too long without anything significant happening and your script gets pulled into that “indie boring void” that so often dooms an indie film. Don’t become another one of those indie films.

All this week, I’ve been putting one of YOUR dialogue scenes up against a pro’s. My job, and your job as readers of Scriptshadow, is to figure out why the dialogue in the pro scenes works better. The ultimate goal is to learn as much as we can about dialogue. It’s a tricky skill to master so hopefully these exercises can help demystify it. And now, for our last dialogue post of the week!

All I know about our first scene is that it’s an introduction to Charlie Lambda, who’s a major character, and Diane, who’s a minor character. It takes place in a bedroom after sex.

The room is cluttered with furniture and wrinkled clothing.

DIANE sprawls across the bed in her underwear, awake. Charlie LAMBDA stands at a dresser mirror, shirtless, buckling his jeans.

DIANE: Leaving so soon?

LAMBDA: Night waits for no one, my dear.

DIANE: Neither do I.

LAMBDA: You wanna leave? Suit yourself. I’ve got money to make.

DIANE: You got a night job?

LAMBDA: Best there is.

DIANE: You a pimp, Lambda?

LAMBDA: You know, most women try to figure people out before they sleep with them.

DIANE: I like mysteries. I like solving them, too.

Lambda grabs a shirt, buttons it up.

LAMBDA: You play cards, Diane?

DIANE: I play poker sometimes.

LAMBDA: You any good at it?

DIANE: I’ve got bad luck.

Lambda chuckles. From the dresser, he picks up a deck of cards. He shuffles them without looking, and they fly from hand to hand and around the deck like magic.

LAMBDA: Luck’s just a matter of stacking the odds in your favor.

DIANE: You still have to shuffle the deck. That’s luck.

LAMBDA: That’s what you think.

He brings the deck over to the bed and hands it to the woman, who sits up.

LAMBDA: Find the aces.

He walks back to the mirror, produces a comb, runs it through his hair. Diane sifts through the deck.

DIANE: So you’re a card shark.

LAMBDA: I’m a professional gambler.

DIANE: And you cheat.

LAMBDA: That’s what makes me a professional.

DIANE: I can’t find the aces.

Lambda goes to the bed, sits beside her, and pats her on the back.

DIANE: You’d take cards over an easy lay?

LAMBDA: It’s better than sex.

DIANE: Oh, really?

LAMBDA: You don’t understand. Playing cards ain’t a game. It’s a way of life. It’s zen. It’s jumping into a pool of sharks and seeing who’s got the coldest blood.

DIANE: And that’s you?

LAMBDA: Babe, Charlie Lambda’s the coolest guy around.

Diane tries to hand him the deck.

LAMBDA: Keep ’em. I’m going hunting.

He goes to the door and opens it.

LAMBDA: Go back to sleep, Diane.

DIANE: If you’re not here when I wake up, I’m gone.

LAMBDA: Wanna bet?

DIANE: Some odds you can’t sway.

Lambda smiles and closes the door behind him. Diane rolls over to go back to sleep– The four aces are stuck in her bra strap.

In this next scene from Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, Joel is coming home on a train. Clementine enters the car and tries to find a place to sit. She eventually sits across the car, facing Joel. After awhile…

CLEMENTINE (calling over the rumble): Hi!

Joel looks over.

JOEL: I’m sorry?

CLEMENTINE: Why?

JOEL: Why what?

CLEMENTINE: Why are you sorry? I just said hi.

JOEL: No, I didn’t know if you were talking to me, so…

She looks around the empty car.

CLEMENTINE: Really?

JOEL (embarrassed) Well, I didn’t want to assume.

CLEMENTINE: Aw, c’mon, live dangerously. Take the leap and assume someone is talking to you in an otherwise empty car.

JOEL: Anyway. Sorry. Hi.

Clementine makes her way down the aisle toward Joel.

CLENTINE: It’s okay if I sit closer? So I don’t have to scream. Not that I don’t need to scream sometimes, believe me. (pause) But I don’t want to bug you if you’re trying to write or something.

JOEL: No, I mean, I don’t know. I can’t really think of much to say probably.

CLEMENTINE: Oh. So…

She hesitates in the middle of the car, looks back where she came from.

JOEL: I mean, it’s okay if you want to sit down here. I didn’t mean to—

CLEMENTINE: No, I don’t want to bother you if you’re trying to—

JOEL: It’s okay, really.

CLEMENTINE: Just, you know, to chat a little, maybe. I have a long trip ahead of me. (sits across aisle from Joel) How far are you going? On the train, I mean, of course.

JOEL: Rockville Center.

CLEMENTINE: Get out! Me too! What are the odds?

JOEL: The weirder part is I think actually I recognize you. I thought that earlier in the diner. That’s why I was looking at you. You work at Borders, right?

CLEMENTINE: Ucch, really? You’re kidding. God. Bizarre small world, huh? Yeah, that’s me: books slave there for, like, five years now.

JOEL: Really? Because—

CLEMENTINE: Jesus, is it five years? I gotta quit right now.

JOEL: — because I go there all the time. I don’t think I ever saw you before.

CLEMENTINE: Well, I’m there. I hide in the back as much as is humanly possible. You have a cell phone? I need to quit right this minute. I’ll call in dead.

JOEL: I don’t have one.

CLEMENTINE: I’ll go on the dole. Like my daddy before me.

JOEL: I noticed your hair. I guess it made an impression on me, that’s why I was pretty sure I recognized you.

CLEMENTINE: Ah, the hair. (studies a strand of hair) Blue, right? It’s called Blue Ruin. The color. Snappy name, huh?

JOEL: I like it.

CLEMENTINE: Blue ruin is cheap gin in case you were wondering.

JOEL: Yeah. Tom Waits says it in—

CLEMENTINE: Exactly. Tom Waits. Which son?

JOEL: I can’t remember.

CLEMENTINE: Anyway, this company makes a whole lie of colors with equally snappy names. Red Menace, Yellow Fever, Green Revolution. That’d be a job, coming up with those names. How do you get a job like that? That’s what I’ll do. Fuck the dole.

JOEL: I don’t really know how—

CLEMENTINE: Purple Haze, Pink Eraser.

JOEL: You think that could possibly be a full-time job? How many hair colors could there be?

CLEMENTINE (pissy): Someone’s got that job. (excited) Agent Orange! I came up with that one. Anyway, there are endless color possibilities and I’d be great at it.

JOEL: I’m sure you would.

CLEMENTINE: My writing career! Your hair written by Clementine Kruczynski. (thought) The Tom Waits album is Rain Dogs.

JOEL: You sure? That doesn’t sound –

CLEMENTINE: I think. Anyway, I’ve tried all their colors. More than once. I’m getting too old for this. But it keeps me from having to develop an actual personality. I apply my personality in a paste. You?

JOEL: Oh, I don’t think that’s the case.

CLEMENTNE: Well, you don’t know me, so… you don’t know, do you?

JOEL: Sorry. I was just trying to be nice.

CLEMENTINE: Yeah, I got it.

I chose these two scenes for a reason. In the first one, we’re looking at two strangers talking AFTER they’ve had sex. In the second, we’re looking at two strangers who’ve just met (before they’ve had sex).

Take note of the energy in each scene. In the first scene, the energy is relaxed, subdued, almost lazy. Which makes sense. They just banged. They’ve already reached the pinnacle of their coupling. Generally speaking, scenes where people are relaxed and happy are bad scenes. You’d rather seek out scenes where there’s tension, where there are problems that need to be addressed.

But in Eternal Sunshine, there’s still an entire world of possibility with these two characters because they haven’t consummated their relationship yet. As a result, their scene’s bursting with nervous energy. There’s excitement in the uncertainty of the moment. We feel tension. We feel hope. We want this to go right.

This is why, generally speaking, you don’t want to consummate the relationship until as deep into the script as possible. Once you do that, the dialogue between the characters loses something. The air will have seeped out of their “relationship balloon” so to speak.

But even if you took all this “consummation” talk away (I was told Diane wasn’t a major character, so maybe we shouldn’t hold her to that status), something’s still missing in that first scene. Let’s take a look at the first exchange. “Leaving so soon?” Diane asks. “Night waits for no one, my dear,” Lambda replies. “Night waits for no one, my dear?” That doesn’t sound like something real people say, does it?

That’s not necessarily a harbinger of doom, though. Some genres produce stylistic dialogue. Take the dialogue in “The Big Lebowski,” for example. Clearly, characters aren’t always talking the way real people talk in that film. The problem is, I’m not getting the sense that that’s what the writer intended here. I feel like this scene is supposed to be grounded. And in that case, lines like “Night waits for no one” come off as overly written, like the writer’s trying too hard.

This cuteness continues when the cards are introduced as a quasi-metaphor. Writing in metaphors (or analogies or clever explanations) is a very writerly thing to do. It gives the impression of depth and cleverness. And it allows you to talk about something by talking about something else. But if the only reason the analogy exists is to achieve this effect, it feels false. It reads as analogy for analogy’s sake.

Now I get the feeling that cards might play a larger role in this movie. If that’s the case, then the introduction of the cards isn’t as misguided. But I think the problem here is the same one we’ve encountered in most of the amateur entries this week. I don’t know what either of these characters wants in the scene! I don’t know if Lambda wants her out or if Diane wants to stay. There’s no clear objective, which means anything they say will appear as “babble” to the reader. It’s not that the dialogue is bad so much as we don’t know the point of it.

Looking at the Eternal Sunshine dialogue, there are two things that stick out. First, the dialogue is much more realistic. It’s short, it’s clipped, it ping-pongs back and forth uncertainly. But most importantly, it’s imperfect. It really feels like two people talking.

That’s a mistake we writers make often. We want our dialogue to be so beautiful, that we carve and mold each line into a perfect specimen of auditory delight. Put a bunch of these ultra-developed lines next to each other and the conversation starts feeling false. We don’t know why, but it does. It isn’t until we realize that no one would actually say any of these individual lines that we understand what’s wrong.

And we never see that problem in Eternal Sunshine. Words are flying by seemingly willy-nilly, with no rhyme or reason. It truly does feel like real life conversation.

Secondly, lots of writers get obsessed with balanced dialogue. Balanced dialogue is when there’s a perfect balance to the conversation. Each word, for the most part, is responded to with a word in kind. “Hey.” “Hiya.” “How’s it going?” “It’s going good. How bout you?” “Going good here.” And back and forth and back and forth in perfect balance.

Real dialogue is unbalanced. It’s often weighted to one side or the other, depending on the character or the situation. Read the bottom half of the Eternal Sunshine scene. Clementine is basically having a conversation with herself. Joel’s just there to hear it. That’s a big reason why this dialogue feels so authentic. Unbalanced dialogue is real life.

What about you? What stuck out to you about today’s scenes? The first one felt a little too “written” to me. But I can see some of you just as easily attacking the “rambling” quality of Eternal Sunshine. Share your thoughts!

What I learned: Balanced versus Unbalanced dialogue. There’s no such thing as perfectly balanced dialogue. Some characters are going to talk more than others. Some characters won’t always answer when asked something. No matter how many times you’ve rewritten your dialogue, it should always feel a little imperfect, a little unevenly weighted.

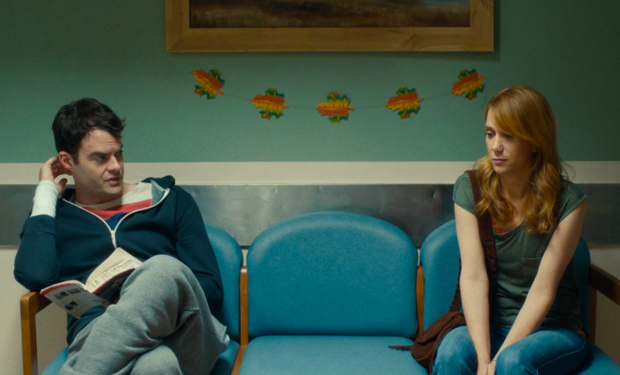

A picture that actually has to DO with today’s dialogue!

A picture that actually has to DO with today’s dialogue!

All this week, I’ll be putting one of YOUR dialogue scenes up against a pro’s. My job, and your job as readers of Scriptshadow, is to figure out why the dialogue in the pro scenes works better. The ultimate goal, this week, is to learn as much as we can about dialogue. It’s a tricky skill to master so hopefully these exercises can help demystify it.

Our first script is a black comedy. The scene takes place in a restaurant between 30-something Ellie and 40-something Patrick. To piss off her brother, Henry, Ellie is going on a date with Patrick. But Ellie doesn’t know a few things. She doesn’t know Henry owes Patrick a lot of money. And she doesn’t know that Patrick is a actually a psychopath. Patrick is also in the dark about the fact that Ellie is Henry’s sister.

Ellie sits with Patrick. They look at menus. Patrick’s phone rings. It’s Henry calling.

PATRICK (turning off phone): This fucking guy. Sorry. You ever just wanna beat someone to death for no good reason?

ELLIE: All the time.

Waitress comes to the table —

WAITRESS: Are you ready to order?

PATRICK (pointing to menus): Does it look like we’re ready to order? Cause our menu’s are open. Look, I’m even pointing to them being open right now.

Waitress blinks and walks away.

PATRICK (CONT’D): People are so rude, you know? They don’t even observe before they speak. Terrible.

ELLIE: It’s the body you gotta worry about… The dead body that would result from the random beating of someone for no good reason.

PATRICK: Oh yeah, but that’s an easy problem to fix and frankly its a very easy problem to fix.

ELLIE: Are you a dead body expert?

PATRICK: I am the dead body expert. Definitely.

ELLIE: “Definitely”, huh? So then, how do you bury a dead body?

PATRICK: Well, it’s not hard really. Shovel, dirt to shovel dirt, garbage bags. Location is more the problem. You gotta have a good locale. It’s like opening a hotel. Same rules, except it’s dead bodies.

ELLIE: So maybe a nice beach-front property? Palm trees.

PATRICK: Well that’s the opposite of what you gotta do. You gotta go for the shit parts. The shit parts of the shit parts. Upstate. Upstate’s really shitty. Just trees there… nobody likes trees.

ELLIE: I hate trees.

PATRICK: Too many leaves.

ELLIE: Yep. Exactly right.

PATRICK (looking at surroundings): Dead bodies, dead bodies, dead bodies…

ELLIE: So what do you really do?

PATRICK: … I work at a strip club.

ELLIE: You own the strip club?

PATRICK: No, I clean shit. I’m a janitor. If I owned it, I wouldn’t be working there. What do you do?

ELLIE: I’m a debt collector.

PATRICK: A debt collector? Why would you do that? You like making people hate you?

ELLIE: It’s a job.

PATRICK: It is a job. It is definitely a job. A terrible job, honestly, getting yourself yelled at all day for a good reason.

ELLIE: And what’s the good reason?

PATRICK: Well, you know, these people are in debt and they don’t need you telling them it.

ELLIE: It’s a job.

PATRICK I know it’s a job. I said it’s a job. I’m just saying it’s a really bad terrible one.

ELLIE: You clean shit for a living.

PATRICK: And puke and piss and I hate it. I got a terrible job.

ELLIE (about to get up, leave): So you have no right criticizing my shit job when you literally have a shit job.

PATRICK: Well then I’m sorry, I really am. But frankly, what I’m saying is I’m tired of a shit life. Literally. I got dreams. Exploration. Don’t you?

That last line resonates with Ellie. She closes her menu. Patrick snaps at the waitress, points to the closed menus, signaling that they’re ready to order.

The second scene is from Silver Linings Playbook. In it, Pat and Tiffany, both mentally troubled, have their first “date” together, although Pat sees Tiffany more as a potential friend. After getting out of the nuthouse, Pat’s sole objective has been to get back together with his wife, Nikki. The scene takes place in a diner where the waitress is pissed that Pat and Tiffany have only ordered a single bowl of cereal and tea.

THE RAISIN BRAN IS DELIVERED BY THE ANNOYED OLDER WAITRESS, who also puts tea in front of Tiffany. Pat opens the little box of cereal and pours it into the bowl.

PAT PEOPLES: Do you want to share this?

TIFFANY: Are you sure?

Pat pushes the bowl of raisin bran to the center of the table. They sit eating their raisin bran in silence.

PAT PEOPLES: How’s your thing going?

TIFFANY: What thing?

PAT PEOPLES: I don’t know, your dancing thing.

She looks at him blankly. Tiffany shrugs and nods.

TIFFANY: It’s fine. How’s your restraining order?

PAT PEOPLES: I’m not sure I’d call the restraining order ‘my thing’, but getting back with Nikki is, and I’ve been doing pretty well except for a minor incident at the doctor’s office–

TIFFANY: And the so-called accident with the weights.

PAT PEOPLES (a little bugged): Yeah. I wish I could explain it all in a letter because it was minor and I can explain it.

TIFFANY: I could get a letter to her, I see her sometimes with my sister.

PAT PEOPLES: Really? Would you do that? Where does she live now?

Tiffany opens her mouth to say, then stops.

TIFFANY: I’d be breaking the law.

PAT PEOPLES: I get it, it’s cool. Is it in this part of town?

TIFFANY: I have enough problems as it is.

PAT PEOPLES: No problem, I get it. So you go to her place?

TIFFANY: With my sister. She’s friends with Veronica.

PAT PEOPLES: Does Ronnie go?

TIFFANY: No, he feels weird about it and he’s super scared of anything to do with the law. Or you.

PAT PEOPLES: It would be so awesome if you could give her a letter from me.

TIFFANY: I’d have to hide it from my sister. She’s not into breaking the law, which the letter would definitely be doing.

PAT PEOPLES: But you’d do it?

TIFFANY: I have to be careful. I’m on thin ice with my family, you should hear how I lost my job.

PAT PEOPLES (CONT’D): How did you lose your job?

TIFFANY: By having sex with everybody at the office.

PAT PEOPLES: EVERYbody?

TIFFANY: I was very depressed after Tommy died. It was a lot of people.

She looks him in the eye, and then down, embarrassed.

PAT PEOPLES: We don’t have to talk about it.

TIFFANY (nods, looking down): Thanks.

PAT PEOPLES: How many people was it?

TIFFANY: 11.

PAT PEOPLES: Wow.

TIFFANY: I know.

PAT PEOPLES: Did you get any diseases?

TIFFANY: No, thank God. [She knocks on the table].

PAT PEOPLES (knocks wood also): What was it like?

TIFFANY: I thought we weren’t gonna talk about this.

PAT PEOPLES: We don’t have to.

TIFFANY: Do you really wanna know?

PAT PEOPLES: Absolutely.

TIFFANY: The good part felt very good, very free, very fun, very alive, and the bad part felt hot at first then lonely, then even more depressed, but I couldn’t stop and it turned into a pattern.

PAT PEOPLES: And you stopped.

TIFFANY: Yeah, I got fired, they put me on some meds, made me go to therapy. I moved home. Things are more steady now. But still lonely.

Pat nods sympathetic, doesn’t want to go there, looks away, changes gears.

PAT PEOPLES: Let’s go back to the letter. What if you secretly gave it to Nikki when your sister was in the bathroom?

TIFFANY: That works.

PAT STANDS ABRUPTLY.

PAT PEOPLES: This is great, I have to go home to write the letter.

TIFFANY: Can I at least finish my tea?

PAT PEOPLES: WAIT. Did Veronica tell Nikki about the dinner we had? Why did your sister invite me? Was it a test?

TIFFANY: I kinda got that feeling, yeah.

PAT PEOPLES: I did a great job. Didn’t I?

TIFFANY: She said you were cool, basically.

PAT PEOPLES: What does ‘basically’ mean, that I’m some percent not cool?

TIFFANY: She said you were, cool but also, you know —

PAT PEOPLES: No, I don’t know.

TIFFANY: How you are. Relax, it’s OK.

PAT PEOPLES: What does that mean, ‘how I am?’

TIFFANY Sort of like me.

PAT PEOPLES: SORT OF LIKE YOU?! I hope to God your sister didn’t say that!

TIFFANY (stung and hurt): Why?!

PAT PEOPLES: Because we’re different people, Tiffany. We can’t be lumped together, Nikki won’t like that.

She looks at him, STUNNED AND HURT.

TIFFANY: You think I’m crazier than you are?!

Pat tilts his head and stares at her, like ‘Come on, it’s obvious.’ TIFFANY’S JAW DROPS, HER FACE TURNS RED, SHE IS FURIOUS. SHE THROWS HER NAPKIN DOWN.

TIFFANY (CONT’D): YOU COCKY, JUDGEMENTAL SON OF A BITCH! [Patrons look] Forget I offered to help, it must be a CRAZY idea because I’m SO MUCH CRAZIER THAN YOU ARE, HA, HAA, HA, HAAA, I’M A CRAZY SLUT WITH A DEAD HUSBAND!

People stare as Tiffany gets up, grabs her purse, and heads for the door as Pat SCRAMBLES to his feet in a panic.

PAT PEOPLES: WAIT! I’m sorry, Tiffany —

HE STARTS AFTER HER, BUT THE WAITRESS STEPS INTO HIS PATH.

OLDER WAITRESS: Slow down, Raisin Bran, we got the check. All $3.79 of it.

SHE TEARS THE CHECK FROM HER PAD AND HANDS IT TO HIM AS HE WATCHES TIFFANY WALK OUT THE DOOR.

PAT PEOPLES: (searches his pockets) Dammit, where is it? I have the money, I swear.

THE WAITRESS WATCHES, DOUBTING HIM. HE PULLS OUT THE TWO TWENTIES.

PAT PEOPLES (CONT’D): Ta-daa! Keep the change.

OLDER WAITRESS Really?! You’re the best tipper I ever met!

PAT PEOPLES (rushing out): Tell that to Nikki.

OLDER WAITRESS: Who the hell is Nikki?

If the posts this week were a competition, today’s entries would’ve finished the closest. Whenever you’re writing a “get to know you” scene, the trick is to do them a little differently. They’re SUCH common scenes that if you don’t find a fresh spin on them, they can die a long boring death on the page.

Which is no problem for these two scenes. Both give us an offbeat intro. Patrick yells at the waitress for asking them if they’re ready to order. And Pat makes the kooky choice of sharing his small bowl of raisin bran with Tiffany. Unexpected choices at the outset of scenes tell me we’re going to get unexpected choices throughout the scene. So in both cases, I was in.

But I think I liked Silver Linings’ a little better. It was easier to read, and a lot of that had to do with its crisp short dialogue lines. Crisp and short leads to a quick rhythm, and I noticed that the chunkier lines in the first scene gave the scene a herkier-jerkier feel.

Plus, I encountered a few of those dreaded “hiccups” in the first scene. Early on, Ellie says, “It’s the body you gotta worry about… The dead body that would result from the random beating of someone for no good reason.” This line had me rubbing my eyes. I’d forgotten we were talking about dead bodies. I don’t know why because when I looked up above, I saw that the first line indeed mentioned dead bodies, but for some reason it didn’t stick, leaving me confused about what Ellie was talking about.

The line itself is also a classic “trip-up” line. “The dead body that would result from the random beating of someone for no good reason.” It’s hard to tell where the word-groupings start and stop in this sentence, making it unclear what exactly’s being said until you sound it out. It’s the writer’s job to identify these hard to read lines and figure out a way to simplify them.

This is followed by “Oh yeah, but that’s an easy problem to fix and frankly it’s a very easy problem to fix.” This is another trip-up line. I think the writer’s trying to be funny here, having the character repeat himself. But I’m not positive. Part of me thinks it’s a mistake. So again, I’m getting “tripped up.” And that’s twice in two lines.

But from there, the dialogue improves. And I generally like how both characters speak, especially Patrick. He doesn’t talk like someone whose every line has been carefully primped and preened for its big moment in the sun. He kind of stumbles over his words, speaks in fragments. “Well that’s the opposite of what you gotta do. You gotta go for the shit parts. The shit parts of the shit parts. Upstate. Upstate’s really shitty. Just trees there… nobody likes trees.” That sounds imperfect and therefore real to me, which is one of the reasons the scene works.

As for as the Silver Linings scene, like all good dialogue, there’s something going on underneath the surface (Tiffany likes Pat and is trying to get him). There’s also conflict, but it’s not as obvious as what we’re used to. Tiffany wants Pat, but Pat isn’t interested in Tiffany. He still loves his ex-wife.

If you look closer, you realize that this conflict drives the scene. We like Tiffany. We want her to get what she wants (Pat). So we stick around to see if she succeeds. In many ways, this becomes a mini-script. Once we know Tiffany’s goal, we can add obstacles to that goal, and those obstacles become the drama that keeps the scene interesting.

For instance, everything’s going well for Tiffany at first. Pat shares a bowl of cereal with her. Score! But then he finds out she can get a note to his wife (obstacle!) and success is in doubt. But Tiffany wisely realizes she can use this this note to her advantage, as a way to spend more time with Pat. But then Pat calls her crazy and she goes ballistic.

I think that’s another reason this dialogue works so well. The scene isn’t a straight line. It has highs and it has lows. Drama IS highs and lows so chances are, if you have these extremes in your scene, we’re going to keep reading.

But the real reason this scene works has nothing to do with the scene itself. It has to do with a decision that was made long before the scene was ever written. The scene works because these two characters are wackadoodles. They’re both “dialogue-friendly” characters. And when you write dialogue-friendly characters into your script, you’re guaranteed to have more instances of good dialogue, especially if they’re the leads in your film. That was the genius of Silver Linings Playbook. It gave us two mentally offbeat characters who naturally say a lot of weird and entertaining shit.

I’m interested to see how you guys call this one. Silver Linings is good but the amateur entry isn’t chopped liver. Weigh in in the comments section!

What I learned: In a “get to know you” scene, one (or both) of your characters will inevitably talk about their past. These stories HAVE TO BE INTERESTING. If you give us some boring shit about how they used to be a first grade teacher but decided to quit and go back to school, you’re better off not mentioning their past at all. Give us something interesting or zip it. Tiffany’s backstory is that she banged 11 guys at work and got fired for it. That’s the kind of story that makes the reader sit up and go, “Whoa.” It’s the kind of backstory that’s WORTH bringing up.