Many people believe that the 70s was the second Golden Era of film, but whether the decade created amazing cinema or not, the reality is there are a lot more forms of entertainment these days, the movie-going demographic has changed, and we’ve been programmed to have shorter attention spans. So no matter how you look at it, the way we tell stories in the medium is different than it used to be. Which makes me nervous about propping up a 70s film to learn screenwriting. With that said, a good story is a good story, and I’m certain that this script would get made today (who would play McMurphy though??). It has that “No. 1 Black List Spot” feel to it. Its secret ingredient is its characters. The film has one of the best collections of characters in history. For those who haven’t seen it, “Nest” is about a convict, McMurphy (Jack Nicholson), who tries to play the system by pretending to be crazy, believing it’ll be a lot easier to do his time in a mental facility than in prison. Once there, he rouses the other patients into action, helping them realize that even if they’re crazy, they can still have fun. But when the floor manager, the deceptively evil Nurse Ratched (one of the best villains ever), sees that she’s losing a hold on the patients because of McMurphy, she finds a horrifying way to solve the problem. One Flew Over The Cuckoo’s Nest won an Oscar for Best Adapted Screenplay.

1) Starting as late into the story as possible – Yesterday we discussed how you want to start your script AS CLOSE TO the main action as possible. Here’s an example of that in action. In the script for “Cuckoo’s Nest,” we start off with McMurphy at prison, showing him causing trouble. Only then does he get sent off to the ward. In the movie, we don’t show that. We just show McMurphy showing up to the mental ward. It was a good decision. Why do you need to show McMurphy causing trouble at a prison when you can just show him causing trouble as soon as he gets to the mental ward? Additionally, we get to jump right into the story.

2) The “Institution Disruption” Flick – They used to do a lot more of these films (Cuckoo’s Nest, Cool Hand Luke, K-Pax, Shawshank) but you don’t see them as often these days. And I’m not sure why. They’re an excellent set-up for a story. You have an institution (prison, mental ward, school, army) that’s running smoothly, then you bring in a dangerous character who upsets the balance of the group. Conflict is built into the premise, since the establishment will want to regain control over the disrupting individual, which means that a lot of the scenes will write themselves (I’ve found that when you introduce natural conflict into a story, scenes write themselves).

3) How to name a villain – This is well-known device, but I’ll repeat it here anyway. To name your villain, find a negative and/or scary word, then move a few letters around until you get something that sounds similar. “Hatchet” is the operative word here, of course. The writers turned that into Nurse “Ratched.”

4) Ironic villains are typically the best villains – Nurse Ratched is one of the best villains in the history of cinema. But is it because she’s an outward bitch? Because she’s always mean? No. Nurse Ratched is actually quite logical. She’s also calm, and she genuinely wants to help everyone. Her motivation is noble. Had Nurse Ratched had a “Wicked Witch of the West” scowl the second we met her, the character would’ve been infinitely less interesting. This is yet another example of writing villains the OPPOSITE of what you’d expect a villain to be.

5) The dialogue before the storm – One of the things a lot of screenwriting books tell you to do (and I’ve said this too) is to start as late into a scene as possible. For example, if two partners are meeting to talk about their failing business, you’d cut to them in an office with the first line being, “How did we get here?” The thing is, you don’t always want to do that. If you do, your script will start to feel rigid and lifeless. Instead, write in some “dialogue before the storm” to give the illusion of “real” conversation. So when McMurphy is called in to the President’s office to discuss why he’s here at the ward, we don’t start with, “Why don’t you tell me why you’re here, Mr. McMurphy.” We start with McMurphy noticing a fishing photo on the president’s desk and asking him about it. It’s a slightly awkward conversation, since the president wasn’t prepared to talk about the photo, but more importantly, it felt natural. I wouldn’t use this approach in every scene. But you should do it every now and then to create the illusion of reality.

6) Give us one scene that encapsulates the world the protagonist is now in – In the “Institution Disruption” flick, it’s vital that you write a scene that shows the audience exactly what kind of world we’re in. One of the first scenes in “Cuckoo’s Nest” is McMurphy taking part in his first “Group Therapy” session. In it, one of the characters starts yelling at another. Another one quickly breaks down. Another one starts rocking back and forth. Everybody else takes sides, until everyone’s either screaming or yelling or arguing or rocking or making noises. McMurphy looks around at all this chaos. It’s at that moment that we know exactly what kind of world we’re in.

7) Mid-point shift – Remember that the mid-point shift is the moment in your script (roughly the middle of the movie) where something happens that SHIFTS the story in a slightly different direction. Without it, your script will start to feel redundant. The mid-point shift in “Cuckoo’s Nest” happens subtly, when McMurhpy brags to one of the guards that he’s getting out in two months. The guard corrects him. His prison sentence may have had two months left on it. But here at the mental ward, they can keep you… forever. McMurphy’s world is rocked. He had no idea that was the case. Now his “goal” shifts from “act crazy” to “escape.”

8) How to build characters in an ensemble – When you have a bunch of characters in a group, you don’t have time to explore them all. But each of them must still be memorable. To achieve this, give each of them ONE DOMINANT MEMORABLE TRAIT and then keep hitting on that trait throughout the script. One of the patients believes he’s smarter than everyone and looks down on the other patients as a result. Another is the “village idiot” who just smiles all the time. Another just wants everybody to get along. Another has zero self-confidence and is afraid to speak up. When you don’t find that trait, the character will disappear. Christopher Lloyd is actually in “Cuckoo’s Nest,” but you don’t remember him because they didn’t give him a specific trait. You can find this approach in Cuckoo’s Nest, Toy Story, Cool Hand Luke, Shawshank and many other films.

9) The anti-hero method for saving the cat – Anti-heroes shouldn’t save the cat like traditional heroes. Their saving should be a little more complicated. In fact, they might even kick the cat a few times before saving it. If you write them doing something overly nice in a way that’s completely out of character, the story will ring false and the audience will turn on you. The “Save the Cat” moment in Cuckoo’s Nest is when McMurphy tries to befriend the deaf and dumb giant, “Chief.” It’s his support of the character when nobody else supports him, that earns him our sympathy. The amateur writer probably would’ve written this scene with somebody bullying Chief, and McMurphy stepping in to save him. FORCED! Instead, what does McMurphy do? He makes fun of Chief! He does an offensive “How” impression of an Indian. Then does an even more offensive Indian dance to get him to react. It isn’t until later, when he teaches Chief to play basketball, that he starts to help him.

10) Writing a friendship into a story – There’s something about writing a friendship into a story that is so powerful if done right. From McMurhpy and Chief here, to Ratso and Joe Buck in Midnight Cowboy, to Red and Andy in Shawshank, to Vasquez and Drake in Aliens. When you do this, for whatever reason, it makes us like the characters twice as much. You guys are welcome to hypothesize on why this is, but all I know is that watching Chief and McMurhpy become friends made me like each of them that much more.

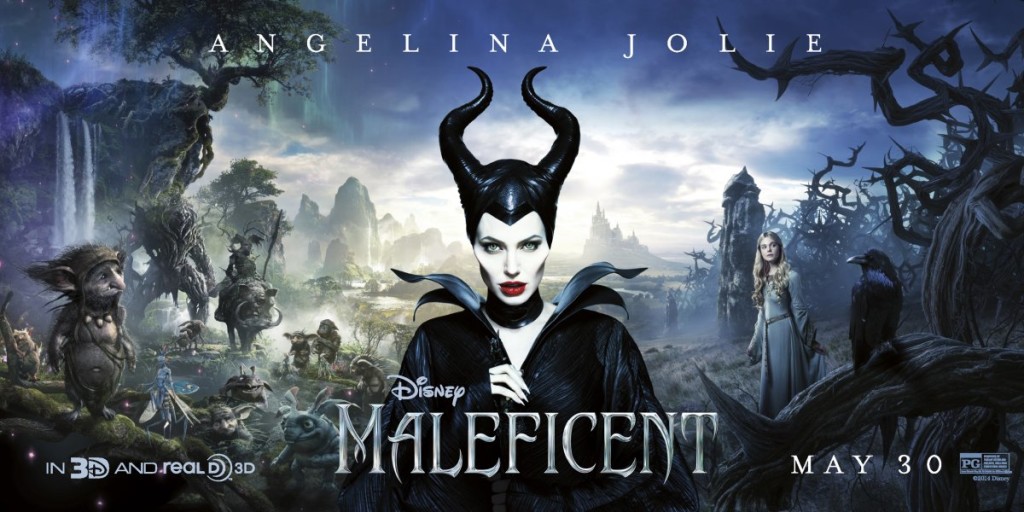

Genre: Fantasy/Family

Premise: (from IMDB) A vindictive fairy is driven to curse an infant princess only to realize the child may be the only one who can restore peace.

About: Malificent is one of the more daring movies Disney has ever released. As the title implies, the film is centered around one of the most famous villains of all time, Sleeping Beauty’s “Malificent.” For Disney to center a film around a villain is one thing, but to center it around a character this evil is a surprising move. Releasing the film in the middle of the year’s biggest movie season is yet another gamble. You’re competing against X-Men, Spider men, and really muscular men, all with bigger fan bases. I have to admit I’m fascinated by this choice, and am eager to see if anyone shows up. Writer Linda Woolverton has been writing for Disney forever. She wrote 2010’s Alice in Wonderland as well as the classics, The Lion King and Beauty and the Beast. In other words, if you’re going to do something daring with a Disney property, this is the woman you want writing it.

Writer: There’s no title page here, but this draft looks to have been written by Linda Woolverton. Disney favorite John Lee Hancock helped with rewrites on later drafts.

Details: 110 pages (unknown draft)

One of the age-old questions in screenwriting has been, “How do you make an audience root for an unlikable hero?” It’s easy to make someone root for an underdog like Forrest Gump or Wall-E. It’s not as easy to make them root for Captain Jack Sparrow or Cool Hand Luke. This question resurfaced when I heard they were having a hard time coming up with a Boba Fett spin-off film for the Star Wars franchise. Boba Fett is a bad guy. How do you make him the hero?

This argument typically parlays itself into the emergence of an antihero. In those cases our protagonist is just as bad as he is good, which makes us a little more uncomfortable about rooting for him. If you do this right, you can create a classic character. Everyone loves themselves a Jack Sparrow. But the ingredients are trickier to mix with anti-heroes. An extra dash here or a tiny spill there can be the difference between a perfect protagonist and a despicable one. Let’s find out which side of the forest Maleficent ended up on.

Now, I haven’t seen Sleeping Beauty in maybe 20 years. So I had to do some Wikipedia searching to catch up. But I realized this is basically Maleficent’s side of the Sleeping Beauty story. Maleficent starts out as a young, winged fairy who’s bigger than all the other fairies for some reason. She’s infatuated with a boy named Stefan, and it looks like they’re going to fall in love and get married.

That’s until he betrays her and joins the Human Land. After becoming chummy with the humans, Stefan tries to go back and kill Maleficent (man, that romance ended quickly), but instead is only able to clip off her wings. My man, Stefan. That was a baaaaad move. A wingless Maleficent is an angry Maleficent.

Many years later, Stefan becomes king (after standing by while the real king chokes to death – classy move) and has a child. This child’s name is Aurora (Aurora is the name of Sleeping Beauty. Did you know that? I didn’t. I thought her actual name was “Sleeping Beauty”). After a confusing array of events, a fairy casts a spell on Aurora that says when she turns 16, she’ll fall into a deep sleep and won’t wake up until her true love kisses her.

Afraid of Maleficent, Stefan hides Aurora in the forest with the fairies until she’s 16. But that incredibly genius idea turns out to backfire, since Maleficent lives in a hut only a short walk away. The two eventually meet up (ON PAGE 75 – THREE-QUARTERS OF THE WAY INTO THE STORY), and Maleficent actually ends up liking Aurora.

The two become friends, however, when Aurora turns 16, she falls into that deep sleep. Maleficent realizes she’s screwed, since there’s no one in the land whose kiss can wake her up. Which means she’ll have to find another solution. Whatever will that solution be….?

Before we even get to the antihero stuff, I have to say how freaking messy the structure of this script was. It kept jumping forward in time over and over again. No story was able to start as just when we’d get close to something happening, we’d jump again. We jump from Maleficent’s teenage years, to her young adult years. And then Stefan has Aurora, and SHE has to grow up, so we have to bumble through another 16 years. Which is why it took until page 75(!) before our two key characters even met!

I think that’s insane. Whenever you write a script, one of the key decisions you have to make is where to start your story. The idea is to start as CLOSE TO THE ‘KEY STORY’ as possible. The further back you start from that moment, the more mud you have to drag the reader through to get to the good stuff.

Take Die Hard for example. We could’ve started that movie back in New York. We could’ve watched John and his wife get married, have kids, fight, her get the job in LA, leave, see him alone for awhile, AND THEN show him come to Los Angeles. But how boring would it have been to slog through all of that? Instead, we started with John showing up in LA so we could get to the good stuff as soon as possible.

To me, the story here is Maleficent and Aurora. So why are we only getting to that on page 75? I understand that the movie is called “Maleficent” and they probably want to explore how she became this evil person, but to have to sit through 5 time bumps just to get to the good stuff? That feels sloppy to me. And the truth is, they didn’t even do a good job explaining how she became evil. Stefan betrayed her, but she was already a bitch before that.

Look at another fairy tale, Shrek. The timeline for that was three days! You can have time jumps in a script, of course, but you should try to contain them inside the first 15 pages if possible. Whether it be with Up or Frozen, we pass all the time we need to pass immediately, and then we can get to the story.

Now, on to the question of the day. How was Maleficent as an antihero? This is how I saw it: I never learned why Maleficent was a bitch. She hated humans from the beginning of the script, so I didn’t gain any understanding of why she was who she was. It’s not that I NEED to know that with every character. But this script is practically screaming the fact that it’s going to tell us this girl’s origins. So why aren’t we learning her origins?

Eventually Stefan steals her wings and becomes the king, setting him up as our “true” villain in the story. But I didn’t think he was any worse than Maleficent. A trick to making an audience like an antihero is to write a villain that’s way worse than him/her. We’ll want the villain to go down so much that we won’t mind rooting for a “bad” hero. But again, these two seemed about the same to me (with a VERY SLIGHT advantage going to Maleficent), so I didn’t have a rooting interest.

It seems to me that this story is banking on the fact that you know the Sleeping Beauty story like the back of your hand, and therefore will wait patiently until the Maleficent/Aurora storyline arrives. But since this will be for children, will these children have seen Sleeping Beauty? Likewise, will the parents remember it well enough (again, I forgot that Aurora was the name of Sleeping Beauty)? I don’t know. We’ll have to see.

One thing I’ll give credit to Disney for is taking a chance. This is unlike anything they’ve ever done before. And with all the money they’re making lately (no one’s making more bank than Disney these days), they should be taking chances. Unfortunately, I don’t think this chance paid off, UNLESS John Lee Hancock did an Almost Page 1 rewrite on it. We’ll have to see. But I’ll ask you guys in the meantime, especially parents with children. Are you interested in seeing this film?

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Dichotomy with anti-heroes – The trick with anti-heroes is to give them ONE GOOD THING they’ve got going for them (so there’s SOMETHING to root for), and then one element of darkness. That dichotomy of light and dark is what makes these characters so fascinating. A lot of the time, the “good trait” is humor (Jack Sparrow, Tony Stark, Cool Hand Luke, Randle McMurphy from Cuckoo’s Nest). And the “darkness” is self-destructive behavior (Henry Hill, Jordan Belforte). In extreme cases, the darkness is sociopathic or even psychotic behavior (Patrick Bateman from American Psycho). If you don’t have that perfect light/dark balance with your antihero, chances are, we’re not going to care about them. I’m not saying I didn’t care for Maleficent, but she definitely wasn’t interesting enough to keep me engaged the entire read.

This is your chance to discuss the week’s amateur scripts, offered originally in the Scriptshadow newsletter. The primary goal for this discussion is to find out which script(s) is the best candidate for a future Amateur Friday review. The secondary goal is to keep things positive in the comments with constructive criticism.

Below are the scripts up for review, along with the download links. Want to receive the scripts early? Head over to the Contact page, e-mail us, and “Opt In” to the newsletter.

Happy reading!

TITLE: LOWLIFE

GENRE: CRIME THRILLER

LOGLINE: With a newborn in a coma, a small-time enforcer is pushed deeper into a world of violence and deceit when he finds himself indebted to the dirtiest cop on the street.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: I have spent way too much time polishing this thing to just let it go. It placed in the quarter-finals of the Nicholl’s last year and the semi-finals of the Screencraft Fellowship earlier this year, but the real goal here is to have it posted on AOW. I have submitted it before with no results, but this draft is not only the latest, not only the greatest, but the last. I’m moving on to other projects and putting this in my arsenal for now, but not without trying to get it out to my fellow SS commentators one more time.

TITLE: A Cinematic End

GENRE: Contained Thriller/ Dark Comedy

LOGLINE: A man retreats to his secluded cabin to commit suicide. His plans are delayed when movie characters start showing up.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: Because the logline grabbed your attention. I also whipped up this poster to get some additional interest going: http://imgur.com/LW8xcSq

TITLE: Knit Wits.pdf)

GENRE: Comedy

LOGLINE: After the passing of their mother, three estranged brothers must reunite and take over the family knitting business.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: “Knit Wits” is a cross between “Horrible Bosses” and “Silver Linings Playbook.” It’s an edgy comedy with a lot of heart that focuses on three men running a knitting business. Now, I tried to learn how to knit in order to do some research before writing the script, but it was a total nightmare. Much of that frustration is showcased in this spec. Knitting is not for me. However, writing about it in a comedic way is much more my style and a hell of a lot more fun!

TITLE: Simple Acts

GENRE: Dramedy

LOGLINE: A cynical self-destructive film critic finds a new perspective on life through a close-knit benevolent family.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: Having read hundreds of amateur screenplays on my job and only finding about 2% of them to be competent, I completely empathize with you when so many of the scripts you read get a ‘wasn’t for me’. I feel the pain dawg! I thought I should give you a script which charms and entertains you enough so that the time and efforts you spend on reading it is rewarded with at least a few chuckles and smiles.

TITLE: The Devil’s Hammer

GENRE: Horror

LOGLINE: When an outlaw biker, and soon to be father, attempts to leave the sins of his old life behind, he is pushed by a vengeful Sheriff into the arms of an ancient cult of disease worshiping sadists.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: I possess a Bachelor of Liberal Arts from Harvard University and have written published columns for multiple notable financial sites such as; Seeking Alpha, Morning Star and Yahoo Finance. On-top of all this, I am a kid from the streets, who grew up in squats, and gang life. This screenplay hits home for me.

Get Your Script Reviewed On Scriptshadow!: To submit your script for an Amateur Review, send in a PDF of your script, along with the title, genre, logline, and finally, something interesting about yourself and/or your script that you’d like us to post along with the script if reviewed. Use my submission address please: Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Remember that your script will be posted. If you’re nervous about the effects of a bad review, feel free to use an alias name and/or title. It’s a good idea to resubmit every couple of weeks so your submission stays near the top.

Genre: Sci-Fi Action Thriller

Premise (from writers): Set in a post-apocalyptic NYC ravaged by a rapid-aging virus, THE MAYFLY follows a soldier who lives his entire life in one day, as he goes against his training to transport an uninfected woman to safety.

Why You Should Read (from writer): We’ve been pitching THE MAYFLY as, “Children of Men meets Escape From New York,” but the premise is best explained by a single question: What if you lived your entire life, from infancy to old age, in 24 hours? There is a chapter in Alan Lightman’s “Einstein’s Dreams” that explores a similar concept, except his story doesn’t include a certified bad-ass who attempts to reverse the state of the world before his time is up. In other words, Alan shit the bed, so we changed the sheets. Every screenplay is hard work. Every screenplay is a labor of love. Not every screenplay is good. Although it took us a while to get here, we believe we’ve reached the point in our journey as screenwriters where we know the difference. We humbly submit our egos to the counsel and would love some help in continuing to develop this script.

Writers: Ryan Curtin & Todd Kirby

Details: 107 pages

The prototypical actor who can play young and old.

The prototypical actor who can play young and old.

So yesterday I got a little rant-y and overly negative. I actually don’t think screenwriting is dead or anything ridiculous like that. And while the spec system is rigged to resist more thoughtful work, that doesn’t mean you can’t trick it. It doesn’t mean you can’t slip a lobster inside the Big Mac you’re serving them. You just have to be sly about it.

One of the things I complained about yesterday was this notion of “effort.” Or “lack of it.” Because a good script is so hard to write, anything less than everything you’ve got isn’t going to be good enough. So when I see shoddy scripts with only the barest grasp of storytelling, I wilt like an aged dandelion. Whether your script is the best script in the world or the worst piece of shit in 9 counties, I want to be able to tell that you gave it your all.

I believe today’s writers gave it their all, or a pretty close approximation to it. The amount of world-building alone indicates they thought a lot about it. My question would be, did they put TOO MUCH into it? Let’s look at The Mayfly’s plot and then I’ll explain what I mean.

It’s the far-off future just outside Manhattan. To bring you up to speed, some war-hungry dimwit created a fast-aging virus that nearly wiped out all of mankind. Earth’s most recent generation still has to deal with this moron’s creation, as some people have the fast-aging virus and some don’t. Some people live till they’re 60. Some live till they’re 1 day old. It’s a crap shoot. Oh, and if you live for one day, you grow up and live your whole life in that day, baby to old man.

This is where it gets a little confusing. The people of Alistair Kingdom have a King who’s looking for a “breeder” to help continue the Royal bloodline. Breeders don’t have “die early” blood. Breeders have a normal life expectancy. Which makes them rare. Problem is, this breeder chick they need is in Manhattan. How the King knows this, I’m not sure. But he does.

The king nominates half-day old soldier, Morrow, to retrieve the breeder. Yes, Morrow is half a day old. But he looks like he’s 30. And he somehow has the intelligence of a 30 year-old, which I didn’t quite understand. But Morrow, being so young and therefore easy to manipulate, believes everything the King tells him, and goes off to secure the Breeder.

Once he finds her (Margo) he pulls a “Midnight Run” and handcuffs her, then starts back home, Shrek-style. You gotta remember, this guy’s got to move. It’s not like he can head home tomorrow. He’ll be dead. On their way back, Margo tells Morrow that he’s been fed lies. That the King of Alistair is purposefully letting people die for his own gain. Instead of offering her up as a sex slave, he should take her to something called “The Program” – where scientists still try to save humanity.

Morrow is torn, but eventually decides against it. His allegiance is to the King. However, after he takes her home and sees how she’s treated, he realizes how wrong he was, and that he must save poor Margo, all before he dies at the end of the day.

So in last night’s newsletter, I brought up something called “The Burden of Investment.” And what it amounts to is, how much information is the writer forcing you to take in before you can enjoy their story? How many characters, worlds, rules – essentially, how much exposition do we have to sit through before we can be entertained?

The Mayfly had a very high burden of investment. There was a Kingdom. There was a past virus. This virus acts differently/randomly for each person. There are p-counts. There are breeders. There are uninfected breeders. There are “IDs.” There are CONS. There are CONS pretending to be IDs.

My brain was so fried after 20 pages, I was pointing right while saying left. The problem when you have such a high burden of investment, is you risk losing your reader. Because there’s so much coming at the reader, it’s hard for them to pick out the essential story beats that convey the central plot.

The story’s clear to the writer because he’s gone over it 300 times. We’ve gone over it one time. That’s what happened to me. I understood that Morrow was going after this girl in Manhattan, but I wasn’t exactly sure why (till later). That’s not to say the answer wasn’t there. It’s that it may have gotten lost inside all those other things the writer was trying to tell us.

I understand this is sci-fi and there’s going to be some world-building involved, but one of the first things I tell sci-fi writers is, “Don’t let things get too complicated. Don’t lose the reader by setting up and explaining ten thousand things right away.”

This may sound contradictory to what I wrote yesterday – when I said I wanted more depth in screenplays – but depth doesn’t mean over-complicating and over-populating and confusing your reader. That’s a different thing entirely, and the overwhelming amount of information being conveyed in the opening act of The Mayfly was too much for my little fried brain to handle.

It feels a little like Ryan and Todd came up with this idea and despite realizing it was always going to be a battle, they were going to do it anyway. Through hell or high water. And there’s a part of me that admires that stubbornness. I think it’s important to challenge yourselves as writers. But there’s another part of me that says, “Why torture yourself?”

I mean, there are still very basic things I’m miffed about that seem directly related to the concept. How do these people learn to be human in one day? How are they speaking fluent English by 9am? How do they learn how to fight or be a warrior? By noon, no less? Even in the most optimistic scenario, wouldn’t it take an adult a couple of days to learn how to walk? That was a huge problem for me, was that I never fully embraced the premise. That’s not to say it wasn’t interesting. It’s just one of those premises where you’re always aware of it, where you’re always wondering how they’re going to pull it off as opposed to just enjoying the story.

Did Ryan and Todd try to do too much? Did having a kingdom in the future along with all these complicated factions/rules take precedence over exploiting the theme at the very core of the concept – aging? That’s something I kept asking myself. This seemed to be more about continuing bloodlines than realizing how short life was. I mean aging’s brought up a few times (for example, Morrow’s never going to see a sunrise) but it’s through dialogue and it feels inconsequential. The theme of aging and time passing should have been explored a lot more thoroughly here.

The writers bring up comparisons to Children of Men, and one of the reasons that movie worked so well was that it was so simple. There wasn’t any complex mythology with Kings and Princes. That’s why I tell sci-fi writers that if they can keep their futuristic societies relatively close to current society, they should do it. Because then you don’t have to spend half your script explaining shit, like a whole new political system.

I’m really torn on this. Does The Mayfly really get better if you ditch all the Kingdom stuff? It seems like the story wouldn’t be burdened with so many limitations that way. Then again, some of the better character moments happen inside the Royal Family (I liked the complex family dynamics of creating an heir).

But yeah, the more I think about it, the more I believe there were too many ideas crammed into here. And it hurt the story. Morrow and Margo rarely got a chance to talk about anything real (life, love, happiness, loneliness, fear) because they were always focusing on p-counts and breeders and bloodlines and Cons. Once exposition takes precedence over character, you’re in trouble. But it’s often the price you pay when you try and over-mythologize a script.

Moving forward, I’d try to streamline the opening act. Strip out as much information as you can and make the world of Mayfly as easy to understand as possible. You do that – this script is going to be so much better.

Script link: The Mayfly

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Reader Reminders – When you’re writing one of these scripts with SO much information, you might want to repeat the protagonist goal for the audience a second time. I didn’t know why they were going after Margo here. The answer was in there somewhere, but it got lost inside all the information dumps. So it was nice when, later, Morrow reminds us that they’re getting Margo in order to continue the Royal bloodline. If your plot is simple, you won’t have to do this. It’s only required when your setup is packed with information and exposition.

The disappointing showing of Transcendence really bummed me out this weekend. Not because I had anything invested in the film. It was just one of the few non-IP properties that made it to the big screen. And for screenwriters who still believe in original ideas, it’s very important that these movies do well. Because if they don’t, we’re bound to turn into an all IP industry.

The thing is, right now, the studios would have a good case against the spec world for doing so. Nobody’s writing anything good, so why should they buy any specs or make any specs into movies?

I’ve thought about this a lot lately, and I’ve noticed some real problems in the system. One of the reasons I tell everyone to simplify their stories and make sure their GSU (goals, stakes, urgency) is strong, is because these are the only scripts that get past script readers. They’re the thrillers and the comedies that have clean easy-to-understand stories, and therefore they can pass up to their bosses without fearing the dreaded, “What the fuck is this?? Give me something I can sell!”

So what does that say to us? It says we can’t explore anything too complex. We have to stay in that little box. In many ways, specs are like the Big Mac trying to compete with the studios’ lobster. We’re not allowed to create something challenging or unique or with substance, so how the hell are we supposed to compete with projects like “The Wolf of Wall Street” or “Benjamin Button?” If neither of those projects were based on IP, they wouldn’t have sold. And that’s really hard to accept. That the playing field is so uneven.

Despite that, I don’t think writers are giving it their best. Even with that reasonable excuse, I’m not reading enough good material. And I’ve tried to figure out why. Part of me believes that screenwriting is SO much harder than everyone thinks it is. There’s so much you have to know how to do.

You have to create intriguing likable protagonists that don’t feel like every other intriguing likable protagonist we’ve seen. You have to know how to pace a script with act breaks and story beats. You have to know what conflict is so you can write entertaining scenes (I can’t tell you how often I see all 55 scenes in a script, and not a single one has conflict).

You have to know how to explore a character in a way that adds depth, and to create relationships with problems that need to be resolved. You need to know how to write dialogue that does more than simply allow two characters to speak. It must push them to speak in a way that ENTERTAINS US. You need to know how to apply suspense, obstacles, setups, payoffs, urgency, stakes. And after you figure all that stuff out, you actually have to apply it in a NATURAL way that doesn’t look like there’s any craft to it. You have to build a house that looks like it’s always been there.

And that’s hard to do.

Part of the problem is too many writers are trying for the quick fixes. They read a couple of things from this site, a couple of things from another site, and they think they’re ready to go. You can spot these scripts a mile away. There’s just no sense whatsoever that the writer’s put anything into the craft. A couple of months back I read an amateur writer’s script, and he wanted to know if his hero should secretly be the killer. I was like, “I’m not even clear what’s going on in YOUR FIRST SCENE.” Whether the killer is the bad guy or not is irrelevant. You need to figure out how to write a scene first (a scene is a story. Start with some problem your characters have to deal with, and you should come up with something reasonably good).

And that’s something I just don’t think people do anymore. Actually WORK. I came across this short last week (The Long Game) which talks about all the geniuses throughout history. Da Vinci, John Coltrane, Stephen King, people of that stature. And what the director found was that there was this period in each of these artists’ lives that he called the “Difficult Years,” where they went through this self-appointed apprenticeship. This apprenticeship would last somewhere between 7-15 years, and would consist of them practicing and experimenting and writing and reading and playing and studying, and looking for any little thing that could make them better, that would give them an edge on, or help them catch up to, their competition.

Nobody talks about those years cause they’re not decorated with No. 1 hits or groundbreaking sculptures or Pulitzer prizes. But those are the MOST IMPORTANT YEARS of the artist’s life. Coltrane spent 15 years practicing relentlessly EVERY DAY on his saxophone until he got his first real gig. And this is the best saxophonist ever! It took him 15 years of practice!

In the documentary “Jiro Dreams of Sushi,” about the best sushi chef in the world, this guy spent something like 10 years studying RICE! What region the best rice came from, the textures that worked best, how to store it, how to cook it. We’re not even talking about the fish. We’re talking about the RICE. That’s why he’s the best in the world. Because he dedicated himself to finding the perfect EVERYTHING for his food. What are you doing as a screenwriter that’s setting you apart from everyone else?

I think I know why this is such a problem for our industry. It’s because screenwriting DOESN’T LOOK THAT HARD. Why would anyone work hard at something that seems so easy? Everybody thinks they can write a screenplay. They look at what’s out in the theaters and say, “I can do better than that guy.” No, you can’t. That’s exactly WHY screenwriting is so hard, is because even the best screenwriters can’t come up with something “better than that.”

As a writer, you should be obsessively doing three things. You should be writing, you should be reading (scripts/books), and you should be studying. If you really want to have a shot at this, you have to outwork everyone else. So I challenge you. All those things I noted above (obstacles, conflict, etc.), I want you to MASTER ALL OF THEM. Work on them until your fingers bleed. That’s the only chance you have of writing something great, is if you master all the aspects of storytelling.

Now I realize that’s a tall order, so maybe I can help you focus a little. If there’s one thing I see botched over and over again – the biggest problem I see in screenplays by far – it’s boring characters. And derivative characters. Or the worst – the combos: Derivabores. So start there. Learn how to write good characters. Look back through my archives. Google the word. Re-watch all your favorite characters and take notes about why you love them.

Because the more I read, the more I realize that it’s ALL ABOUT THE CHARACTERS. If you write a bad story, you can make up for it with good characters. A great place to start is by doing the PLOT STRIP TEST. Mentally strip your plot OUT of your script and just look at your characters all by their naked selves.

Now tell me, are these characters interesting without the plot behind them? Without the explosions or the twists or the killer concept? In a script I read awhile back, I did the PLOT STRIP TEST, and here’s all that was left: A hero that was afraid of heights and a love interest who was upset that her dad died. Do those sound like interesting people to you?

Where is the flaw (she’s unable to love), the vice (she’s a sex addict), the relationship problems (these two were together once until she made a mistake and cheated on him). What’s their personality like (wise-ass)? What do they fear (sleeping alone)? What do they keep from the world (they once watched a friend rape someone and didn’t do anything about it)? I don’t want to use the dirty words “soap opera,” but you almost have to think of it that way. Are my characters interesting on their own, without the story? Because if not, you need to build a lot more into them.

But characters are still just one piece of the puzzle. Sometimes I’ll pick up a script and I don’t know what’s wrong with it. I just know that it’s lifeless, that it’s missing something.

So maybe I’ll turn to you guys for help. What do you think’s missing from today’s scripts? A lot of you called Transcendence a “bad screenplay.” What’s missing from it and other scripts like it? What is that one thing that all these writers (amateur and professional) continue to ignore?

And hey, if you think you’ve done everything I’ve said above and that you’re ready, well dog gonnit, send your script in for Amateur Friday (details at top of page). Maybe you’ll get reviewed and blow us all away. I hope so. Because baby, I want to believe again.

Oh, and finally, I’m sending out a new newsletter late tonight, and it’s going to be a good one. I’ll be reviewing a script from one of my FAVORITE writers, as well as posting some short films for you to check out. Make sure to check your SPAM boxes if you don’t receive it, and add me as a contact so it doesn’t go to SPAM in the future. If you’re new to Scriptshadow and want to sign up, go here!