Mistake #15 – Too many characters!

Mistake #15 – Too many characters!

After consulting on a script last week, the writer asked me, “Is there anything in my script that screams amateur?” I found that to be an interesting question. As writers, avoiding that amateur status is a must. No one wants to cluelessly show up to their first hockey practice wearing a football helmet. Now the truth is, the best way to shake off all the amateur mistakes is through good old fashioned practice. But we at Scriptshadow are committed to speeding that process up.

So today, I’m going to list the top 21 amateur mistakes I encounter. If I see any of these in a script, I know I’m dealing with an amateur. But instead of listing them for you in order of frequency, I’m going to list them in order of importance. So the number 1 mistake is the absolute WORST amateur mistake you can make. The number 2 mistake, the second worst, etc., etc. Oh, and because I love you guys so much, I’m going to give you 21 little mini-solutions to these mistakes. Are we ready? Let’s do it.

1) Bad Concept – Boring, uninspired, and drama-less movie ideas are the most crippling mistake you can make as an amateur. Your script is dead before the reader has even made it to the first word of your screenplay.

Solution – Always field test your ideas. Go off the energy of the reaction rather than the words. If someone looks and sounds excited after you give them the logline, it’s a good idea. If someone acts reserved, confused or polite, it probably means they don’t like the idea, even if they say they do. Of course, get different opinions. No idea is universally loved.

2) Passive/Reactive Protagonist – If your hero is not actively pursuing something in your script, that means he’s sitting around waiting for things to happen, which means your story is probably waiting around too. There are some movies that don’t have big goals driving the story, but they’re often niche material and they’re often not very good.

Solution – Make sure your hero always has a goal at every point in the story. If they achieve one goal, give them another.

3) Cliché – Everything from the characters to the scenes to the plot points are stuff we’ve already seen in other movies.

Solution – Stop using choices you’ve seen from other movies. If you’ve seen one of your characters in another movie, change him. If you’ve seen a scene before in another movie, don’t use it. You won’t always succeed, but you should at least try to come up with a fresh take on every choice you make.

4) Lack of effort – Nothing seems very well thought through. Scenes feel empty and rushed. Even character names seem flat (Bob, Joe, Bill). You get the sense that the script was written in a week with the writer never once questioning any of his choices.

Solution – If you want to compete in the big-leagues, you have to bring your A-game. Think through as much of your story as possible before you write it. And always question your choices while you’re writing it. Ask yourself, “Can I write a better scene here?” If the answer is yes, re-write the scene.

5) Thin characters – None of your characters has any depth. They lack flaws, backstory, a compelling worldview, anything interesting to say, or any sense that they existed before they first appeared in your script.

Solution – They’re annoying as hell, but write a 3000-5000 word backstory for all your major characters detailing their life from birth until present day. The more you know about someone, the more real they’ll appear on the page. Also, every person on earth has one major flaw holding them back (even you!). Figure out that flaw in your characters, and make sure it keeps getting in their way throughout the story (if your hero is selfish, keep giving him opportunities to be selfless).

6) No drama – There’s very little conflict, obstacles, or choices that anyone in your story has to deal with. Things are handed to your hero without him having to work for it. Scenes often consist of agreeable characters talking agreeably.

Solution – Start every scene with an imbalance. Someone wants something and the other person doesn’t want to give it to them. That’s not the all-encompassing answer to creating drama, but it’s a start.

7) Unnecessary scenes – Amateurs love to include scenes that have nothing to do with the story. They figure as long as their characters are talking about something, it’ll be “entertaining.”

Solution – Figure out what your hero’s main goal is (defeat the terrorists). If you’re writing a scene that isn’t necessary to your hero achieving that goal, it’s probably not necessary.

8) Slow first act – A close cousin to the above, writers use two, three, even four times the amount of scenes they need to set everything up. They think they’re “adding depth” by building up their world, when in reality, they’re boring the reader, who’s getting impatient because nothing’s happening.

Solution: Things always need to happen faster in your story than you think they do. Move that exciting plot point from page 30 to page 15. Move your big midpoint twist from page 60 to page 45. Get to the good parts sooner, then create more good parts. You’ll thank me.

9) On-the-nose dialogue – Characters say exactly what they’re thinking all the time, leading to predictable and boring dialogue.

Solution: In general, people hide their true thoughts behind facades. The happiest person is sometimes the saddest on the inside. The person who’s the nicest to you may be the one always talking behind your back, or seeking something from you. Always remember that when you write dialogue. There’s usually a hidden agenda.

10) No stakes – Nothing really matters in your story. Your characters will end up in relatively the same position whether they succeed or fail.

Solution – Make sure there’s always something on the line for every character in the screenplay, not just in the overall story, but in each individual scene. The more that’s on the line, the more intense your story or your scene will be.

11) Telling instead of showing – Given the choice between telling the reader something, (“Hey Joe, I heard you’re the best realtor in the state,”) or showing them (a scene where Joe convinces a family hell-bent on not buying a house to buy it) the writer almost universally chooses to tell it. Hence, their script is full of talking heads instead of action.

Solution – This one’s easy. Every time you need to tell the audience something important about your plot or your characters, you’re not allowed to let your characters say it. You have to come up with a way to show it through action instead. Finding the right “show” scene is one of the most rewarding feelings in screenwriting.

12) Lack of clarity – This is one of the hardest ones for an amateur writer to catch because it’s completely beyond their realm of understanding. They don’t yet know how much information to give the reader, so usually border on too little. So the reader’s always confused about what’s going on. These scripts can be mind-numbing to read.

Solution – It’s a bitch finding someone who will do this, but the only way to really nip this in the bud is to have a “clarity” reader, someone who reads your script for clarity issues. After they’re finished, quiz them on all the major plot points and characters. See if they understood everything. If they didn’t, find out why.

13) A wandering second act – Everything seems to be going well at first, but as soon as the writer hits the second act, the script falls off the rails and becomes an unfocused mess.

Solution – Remember, character goals are your friends. As long as your protagonist is going after something important, your script will have direction. The second he isn’t, your script is going to lose steam. Once again, if a goal is met, replace it with another one, preferably one bigger than the last.

14) No urgency – Nobody seems to be in a hurry to do anything. While not as crippling to a screenplay as no goal or no stakes, a script without urgency starts to feel slow and unimportant.

Solution – Even in an indie film, the idea is to always have something your characters are trying to do, and preferably something they need to do quickly. “Quickly” can be relative, but in general, it should feel like your characters are running out of time to do whatever it is they’re trying to do.

15) Over-description – The reason why you see a lot of over-description (“The cool grass nuzzles up against packed dirt as a hulking boot plunges down on the oxygen-dependent blades”) is a) because most new screenwriters write as novel-readers, since that’s the only kind of writing they’ve read up until this point and b) because they want to impress you with how many words they know. Neither is a good thing.

Solution – During important moments (an important character, an important location, an intense scene) that’s when your description should be a little more colorful. Otherwise, keep it simple and clear. It’s a screenplay and meant to be read fast.

16) Too many characters – The writer just keeps introducing them. Every new scene has another character or two. And they actually expect the reader to remember all of them!

Solution: Ultimately, your story will determine the number of characters you include. I read a script last week with 4 characters. I read a script yesterday with 15. Just remember that you usually don’t need as many characters as you think you do. Try to combine or cut characters if possible. Use the extra script time you gain to develop your main characters. If you have over 20 named characters, you probably have too many.

17) Plot is unnecessarily complicated – Amateurs love to make things way more complicated than they need to be. Lots of plot twists. Triple-agents. The guy who works for the secret guy who works for the secreter guy. Complex plots are actually great when done well, but the amateur doesn’t yet know how to navigate these tricky waters. They’re still learning. So it’s a little like watching a 4 year old try to skate an Olympic freestyle routine. Sure, you’re really rooting for them. But after they’ve fallen down five times in a minute, you don’t want to watch anymore.

Solution – Your plot will be determined by your story. Chinatown is going to have more plot than Paul Blart: Mall Cop. But in general, your plot should be simple. Any complexity should be saved for your characters.

18) Terrible use of exposition – Characters talk endlessly about the plot and each other’s backstory, and there’s no attempt to hide this exposition at all.

Solution – However much exposition you think the audience needs, divide that by four. That’s how much you’re allowed to give them. Therefore, find the 25% of your exposition you believe is the most important, and hide it throughout your script in parts.

19) On the nose characters – This usually goes hand-in-hand with on-the-nose dialogue. This includes characters who act and talk exactly how they look. A big muscly guy who has a big burly Brooklyn accent. A small nerdy guy who loves computers. The hot girl is, of course, a bitch. The old hag who lives next door is a giant meanie.

Solution – A form of on-the-nose characters can be okay (by “a form” I mean still adding a twist to them. A meathead can still talk like a meathead, but maybe has some unexpected trait, like he loves cats). But mix in these on-the-nose characters with off-the-nose ones as well. The nerd who’s a stud with the ladies. The basketball star who’s a quiet recluse. The company CEO who’s a jokester. This is one of the easiest ways for me to spot a writer who knows what they’re doing, the ones who create off-the-nose characters.

20) Way too much mindless action – Amateur writers often mistake “something happening” for “lots of action.” But if we don’t know why the action’s happening or know the characters who are in the action well, we won’t care. Check your favorite action movies. Write down the ratio of scenes with action to those without action. You might be surprised at how many non-action scenes there are.

Solution – Put more emphasis on character development instead (putting your hero in situations where his flaw is challenged. So if your character is anti-social, make it so he has to go to a party). That way, when we get to the action scenes, we’ll care more, since we’ll know your characters better and care whether they survive.

21) Spelling/grammar – You might be surprised that this one is so low on the list. But I’d rather have all the things above than good spelling. With that said, bad spelling and bad grammar usually go hand in hand with everything else here. Once people start taking all that other stuff seriously, they take more pride in their presentation.

Solution – Get a proofreader. Either here with us, with someone else, with your friends, family, whoever. But if you want to be taken seriously, your work has to look professional.

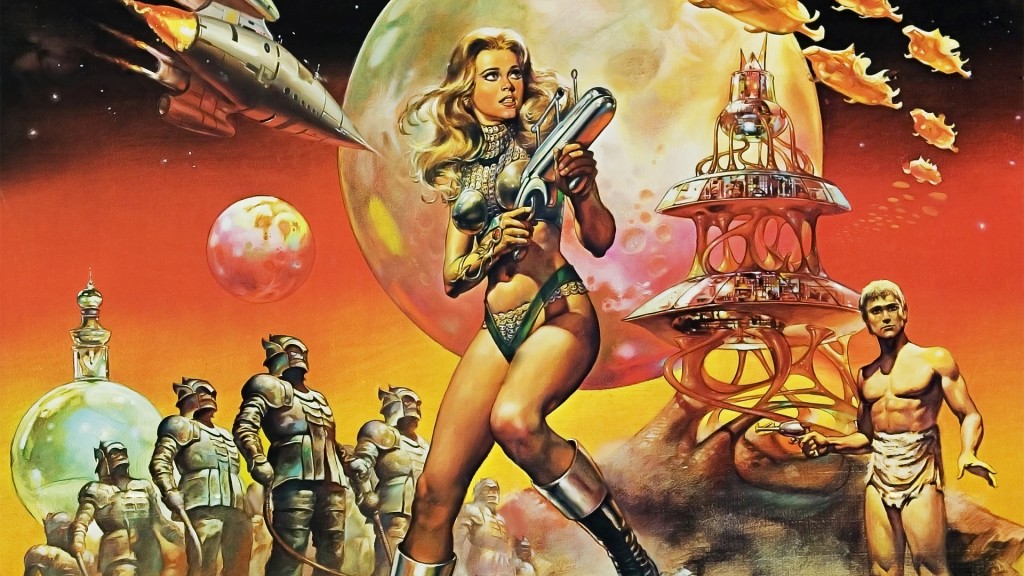

Genre: Sci-fi

Premise: In a universe where men are dying off, a sexy star-cruising bounty hunter named Barbarella finds herself caught up in a plan to save them.

About: The original Barbarella movie, made in 1968, was a critical failure. But a lot of good things came out of it. The costume design had an iconic look to it that would later inspire many artists (including Jean-Paul Gaulteir on The Fifth Element). It also had one of the best posters of all time. It even started Jane Fonda’s career! (okay, it’s debatable whether that was a good thing) They’ve been trying to remake this film FOR-EVER. It got close a few years ago when Robert Rodriguez was planning to direct it. But his insistence on using unproven actress Rose McGowan in the tittle role scared the studio and ultimately killed the project. This version of the script was written by long-time James Bond screenwriters Neal Purvis and Robert Wade (who are also writing Bond 24). Will we ever see a Barbarella remake? I don’t know. But for some reason, I feel like with Nicolas Winding Refn looking to move into bigger movies, this would be perfect for him. They’re both weird and offbeat. Seems like a match made in Refn. Nicolas? Are you out there?

Writers: Neal Purvis and Robert Wade (based on the French comics by Jean-Claude Forest and Claude Brule and the 1968 screenplay by Terry Southern and Roger Vadim).

Details: 89 pages – 2007 draft (alternate ending version)

Barbarella redefined movies.

Okay, even I couldn’t type that with a straight face.

Barbarella’s biggest achievement was that if you came across it on cable, you usually didn’t change the channel. That was for a number of reasons, mainly that Jane Fonda’s outfit allowed you to see her breasts, which was pretty stellar if you were a little boy.

But even without the world’s first deliberate wardrobe malfunction, the movie had a goofy charm to it. Something about it worked, even though the filmmakers themselves would be hard-pressed to point out what that was.

Naturally, with this being Hollywood, they’ve been busting their ass trying to get this back up in theaters. But the Movie Angels have not shined down on the producers, partly because it’s obscure and partly because it objectifies women, something you could get away with back in the 60s, but is a lot harder to do now.

But you can’t fault them for trying. They brought in some heavy hitters to write this draft (the Bond guys) which must have cost them a pretty penny. And I guess it makes sense. Bond uses his sex appeal to smooth-talk his way out of problems. Barbarella uses her sex-appeal to get out of tough spots. Maybe this will work?

Barbarella, our sexy bounty hunter, has just received some bad news. Her evil nemesis, the one-eyed Severin, has escaped from Planet Hulk prison with plans on killing the woman who put her there (that would be Barbarella).

That’s a hefty to-do list for even the strongest heroine, but Barbarella’s ALSO received word that she must travel to the Black Moon to save a king. These orders come from three motley dudes who call themselves The Watchers, who are the last of their kind in the galaxy.

The new boys in town are the “Baal,” an evil race of aliens who now number in the trillions. They’re also trying to find the elusive King, since if they kill him, they can increase their population by… I don’t know, I guess another trillion? (Thinking too deeply about logic in this script is highly discouraged).

Along the way, Barbarella meets a sexy alien named Rael, who only has a 12 year lifespan because someone thought that was a cool idea. But Rael joins her and the two jet off to the Dark Moon, where they find a bunch of men hiding underground, eager to repopulate the galaxy.

Oh yeah, I guess the galaxy is light on men or something? That’s sort of thrown in there towards the end. But yeah, Barbarella finds the king, shuttles him and all his buddies to a planet of Amazonian Jungle women, and the reboot of mankind begins. Yay.

Before we even get to the “story” here, I need to point out that this script used really tight margins and big letters. Which means it’s even shorter than its 90 pages suggests. I’d say its true length is 80 pages. Which means this read should’ve FLOWN by. Yet never has a script read so slow. I had been reading so long, I thought I was almost done with this monstrosity. I was POSITIVE I was at least on page 70. I checked the page number. 33!!! I wanted to kill life.

What was wrong with this script? What wasn’t?

Let’s start with the simple. If you’re going to write a comedy science fiction or comedy fantasy, keep the universe and the plot simple! We’re here to have a good time and laugh. Why would you impede that by building an overly complicated universe with 10 different planets and Watchers and Baals and aliens who only live to 12 for no story reason whatsoever??

I lost interest in this screenplay so quickly because all my energy was focused on figuring out what the hell was going on. Barbarella is secretly the daughter of the King of the Dark Moon, sent here by the Watchers who had actually been tricked by the Baal to lead Barbarella to the Dark Moon King so they could trap him and take over a universe they already own??? I DON’T CARE!

I mean, if you’re writing a Game of Thrones or Dune adaption, dramas where the intricate plots and relationships and backstory are essential to enjoying the story, then a more complicated storyline is understandable. But this is a movie where a woman has replaced one of her nipples with an eyeball!

Whenever you’re brought in to write a remake, one of the things you have to decide is how you’re going to update the material. Are you going to keep the tone the same, or are you going to change it? Make it more current? The further back the original material goes, the more likely it is that you’ll have to update it. I mean a lot has changed since 1968, hasn’t it?

For one, you can’t exploit women onscreen anymore. And whereas we used to forgive our mainstream films for looking cheap and silly (it was part of their charm), these days, the audience requires more of a grounded believable experience (relative to what the movie is). Even Transformers, for how gloriously bad it is, has a strong visual world.

Barbarella feels like it still wants to exist on cheap sets and use bad special effects, like that remake of Escape to New York. Remember how that worked out?

The thing is, it’s got some cool elements to work with. A sexy star-hopping bounty hunter heroine. A badass female nemesis. Why not ditch the midnight-movie angle and build something more grounded in reality? I mean even the affable Clark Kent doesn’t smile these days. It’s not like you’re going to piss off the 7 members of the Barbarella fan base.

And for the Jesus in all of us – people! Stop over-complicating your plots and your worlds when there’s no reason to. If you’re writing Chinatown, yeah, create 10,000 layers of deceit. But if you’re adapting Bob’s Burgers, we don’t need to find out that Bob’s great-grandfather was leader of the CIA and had a daughter who now works for the Russians who’s married to the sister of Fred’s Fries. Stop already!

[x] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: When writing sci-fi, use easy-to-remember names for things like planets, characters, cities, etc. The reader’s forced to remember so much in sci-fi/fantasy, that you have to lighten the memory load for them where you can. You do this by giving people/things names that sound similar to who/what they are. For example, if I named an alien “Occarius,” and didn’t mention him for ten pages, you may not remember him when I brought him back (“Wait, who is Occarius again? Is that Jozzabull’s brother?”). But if I named him “Darth Vader,” that’s a name that’s easy to remember (“Darth” sounds very much like “Dark,” which implies a “bad” person). Ditto the “Death Star.” You know what that is every time I bring it up. I’m not sure that would’ve been the case had I called it “Pomjaria.” Now these choices are always relative to the tone and the story you’re telling. If you’re writing really serious sci-fi, the “Death Star” may sound too much like a B-movie. But the spirit of this tip should remain the same. Any way you can you pick a name that helps the reader remember that thing, do it.

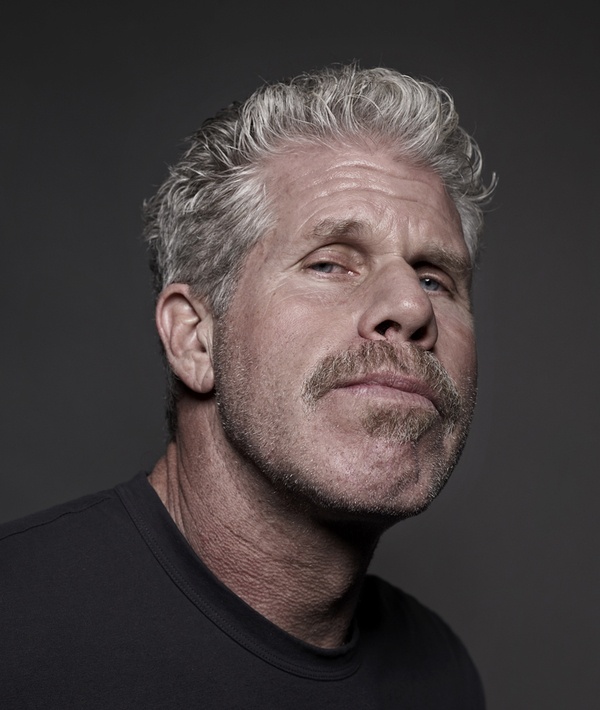

Genre: TV Pilot (Drama)

Premise: After tragedy sends a local judge into a spiritual awakening, he starts making judgements based on faith over fact.

About: Amazon is tired of being left out of the TV discussion so they’ve decided to come hard to the table. “Hand of God” will star everyone’s favorite character actor, Ron Perlman, and have super-helmer Mark Forster (World War Z, Quantum of Solace) directing the pilot. The cool thing about these big TV pilots is that they’re written by “nobodies,” so every time we read one, we get to experience a new voice. “Hand of God” was written by Ben Watkins, whose only work up to this point has been on the show, Burn Notice. Recently, Ben was asked what the most difficult challenge was about this business. He answered, “This business is built on one ridiculous challenge after another. In my opinion, there’s only one condition that is fatal – losing faith in yourself.”

Writer: Ben Watkins

Details: 68 pages

I’m not going to mince any words here. I’m pissed this is going to Amazon. Because if it’s on Amazon, no one’s going to see it. And this is too good of a show (or pilot) not to be seen. I mean honestly, how do you watch a show on Amazon? I go to Amazon and I see 10 billion different links. I’m lucky if I can find the electronics section.

I get that Amazon wants to rule the world but the reason Netflix is so dominant in this space is that you know what it is when you go to it. I want to watch something. Click. Netflix. With Amazon, you have to jump through 18 dozen hoops. Combined with the fact that most people don’t know that Amazon even offers TV shows, and I’m not sure how Hand of God is going to get any attention.

It won’t always be like this. I can see a future (maybe 10 years from now) where TV and cable are dead. Everything will be on demand and a la cart via services like Netflix and Amazon. But we’re not there yet. Which means Hand of God might go down as the best show nobody’s ever seen.

We find 50-something Judge, Pernell Nathaniel Harris, in a park, naked, speaking in tongues. Nobody’s seen him for days and this is how he decides to reintroduce himself. Pernell has a pretty good excuse, though. His son shot himself a few days ago and is brain dead on life support.

As the mayor, attorney general and police chief all try to delicately bring Pernell back to the land of the sane, they realize this religious awakening he’s had isn’t going away. Pernell has pledged his loyalty to a con-artist wacko priest who claims to have a direct line to God – to the tune of a 50 thousand dollar endorsement check.

In the meantime, we learn that the reason Pernell’s son tried to off himself is because seven months ago, he was forced to watch his wife get raped. Although he tried his hardest, he couldn’t live with the fact that he didn’t do more to try and stop it, so a bullet to the cranium seemed like a pleasant way out. Pernell is now on a mission to find the rapist and make him pay for what he did to his step-daughter and son.

The problem is, Pernell’s kind of crazy now. And instead of listening to logic, he’s listening to “God.” Voices and signs have taken precedence over testimony and facts. So when a religious sign points to a random member of the police department as the rapist, the authorities have to stop Pernell from taking the man down. But it’s too late for that. If Pernell has his way, he’s going to make sure Officer Rapist meets his maker, whether he’s proven guilty or not.

Wow.

I think this is my favorite pilot I’ve ever read. Tyrant was good, but this is REALLY good. Speaking of Tyrant, I don’t know what happened to that show. They took a gritty show about 3rd World dictators and tried to turn it into an 8 o’clock NBC family drama. Parenthood 2. Ugh, I’m still smarting from that. But Hand of God is getting me back on track. For a lot of reasons.

First of all, Watkins got the NUMBER ONE thing right when writing a pilot. He wrote a great meaty main character! How ironic is it that a man whose job is based on listening to facts, is making his decisions based purely on faith? Add in a healthy dose of crazy, the fact that he’ll hire hit men to get the job done, and you’ve planted the seeds for one hell of a harvest.

But as we know, every harvest needs rain. And Hand of God’s got plenty of that too.

The opening 10 pages are crucial for ANY script, pilot or feature. And they usually fall into three categories.

1) Nothing interesting happens in the first ten pages at all; I’m miserable that I have to spend the next 2 hours with this thing.

2) One or two interesting things happen in the first 10 pages, enough to pique my interest. I read on with desperate hope.

3) Every single one of the first ten pages is good, in which case, I know the script’s going to be awesome.

Number 3 is a rarity but that’s where Hand of God falls. We start off with this bizarre mystery. A man is naked in a park speaking tongues to the sky. At the end of the scene, we find out he’s a judge. Hmm, how did he get here, we ask? We’re intrigued. We then move to a hospital where a devastated beautiful woman tries to keep him from seeing someone named “PJ?” Who’s PJ. Ahh! We learn he’s Pernell’s son. And he’s in a coma. Why is he in a coma?? What happened? I need to know more!

In other words, there’s a lot going on in the first 10! Usually, amateurs will bumble along in their first 10 pages setting up the characters well, but in boring ways. They don’t have their heroes in parks, naked, speaking in tongues.

I also thought the whole “botched sucide” storyline was a great choice, and I’ll tell you why. 99 out of 100 writers, in order to motivate our hero, would’ve given Pernell a daughter and killed her off. Someone raped and killed her, now he’s out for justice. It would’ve worked, but it WOULD’VE BEEN BORING. Because we’ve fucking seen it before! The quickest way to disappoint a reader is to open the gates to The Kingdom of Safe and Predictable Choices.

The “watched rape/botched suicide” setup poses a more interesting set of questions. There’s not only a rapist on the loose we need to find. But there’s also the question of whether PJ’s wife is going to pull the plug on Pernell’s son or not. A big deal because Pernell, who’s riding dirty on Miracle Lane, now believes PJ will live. But he doesn’t have a say in this decision. And since she doesn’t want to see her husband suffer anymore, she calls to pull the plug. Interesting choices always lead to more interesting choices. Boring choices lead to… well, you get what I’m saying.

Then there were little things that shined like characters playing against the obvious in a scene. When Pernell’s wife goes to threaten Reverend Paul to stay away from her husband, she plays the whole scene calmly and with a smile. Her threats were veiled and implied. A lesser writer would’ve written this more on-the-nose, with the wife coming in and angrily warning Paul to “stay away from my husband!”

We even get some classic urgency (ticking time bomb style) to the pilot, with Pernell’s daughter moving quickly to pull the plug on her husband (in two days!). Pernell’s got to figure out a way to keep him alive, as he believes God will perform that miracle. But he can’t perform a miracle once the plug is pulled.

But what tipped this into the impressive category was the ending. The ending is almost always responsible for whether a script makes the “impressive” list. You can kick ass for 60 pages, but if you suck for the last five, nobody cares. Hand of God gets really good when one of Pernell’s religious visions points the noose at a random man who couldn’t possibly have committed the crime.

Not only are we wondering if he’s going to kill this man, vigilante style, but we’re fascinated by the question of: What if he’s right? I mean what if this totally random man really did commit the crime? What does that mean moving forward? Could Pernell truly be channeling God?

This was a wonderful pilot. Now, if only Amazon can figure out how to show it to people. That would be great! Oh, and since Amazon Studios is all about posting and getting feedback of their projects, I’m including a link to the script. Enjoy!

Screenplay link: Hand of God

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Never set foot in The Kingdom of Safe and Predictable Choices. It’s a land littered with 7-11s, McDonald’s and Supercuts. It’s comfortable. But it’s never inspiring. Aim instead for Paris in spring time.

Genre: Crime/Comedy

Premise: When the female TV star for a popular children’s show commits suicide, two low-life investigators are hired to look into claims that a dead-ringer for the actress has been seen around town.

About: One of the biggest specs out there right now, “The Nice Guys” has actually been around for over a decade, originally written in 2003. But the project has been jolted back to life, with both Russell Crowe and Ryan Gosling preliminarily attached. Shane Black (Lethal Weapon, Iron Man 3) co-wrote the script with Anthony Bagarozzi, who, despite this script being a decade old, is just now seeing his career blow up. He has four projects in various stages of development as a writer or director, including Doc Savage. Important to note: the script I’m reviewing today is the original draft written back in 2003.

Writers: Anthony Bagarozzi & Shane Black

Details: 135 pages (April 14, 2003)

Isn’t Hollywood great? No matter how deep into obscurity you sink, the town will always give you another chance. Shane Black was on one of the biggest screenwriting streaks in history in the 90s, selling every spec that spat out of his printer for a minimum of 1.3 trillion dollars. But then the printer carton burst on stylistic over-the-top dialogue-heavy specs and, Black found himself no longer able to heat his apartment with a fire full of hundred dollar bills.

Oh sure, Black probably got plenty of money in those “lean years” doing rewrites. But once you’ve tasted the frosting at the top of Hollywood’s cake, you never want to go back to the frozen Sara Lee stuff again. So Black did something smart. Instead of waiting for Hollywood to re-recognize his genius again, he directed his own script, Kiss Kiss Bang Bang. And for a brief moment, Black was back.

The flick didn’t make enough money to catapult him back to the top but it just so happened to get him a strong relationship with Robert Downey Jr., who became a super star when he starred in the surprise hit, Iron Man, a few years later.

Fast forward another few years, and guess who was now calling to ask Shane to direct the newest entry in the franchise?

What’s funny about all this is that a script Black wrote all the way back in 2003, which he couldn’t get the local community theater director to read, was now the hottest script in town. Does Black’s return celebrity make this script better than it once was? Or was the script overlooked in the first place? Let’s find out.

Suzy Shoemaker is the adorable 20-something star of one of those kids shows that every 4 year old in the universe loves. She’s also dead. Or, she kills herself at the beginning of the movie after a private sex tape surfaces of her.

Cut to Jackson Healy, a “private enforcer” of sorts, the adult version of a bully-for-hire, who thin-timidates anybody who messes with you, for the right price of course.

If Healy’s low-rent, Holland March is a 20 dollar a month storage unit. The 40-something private investigator makes most of his money by taking advantage of the Alzheimer’s crowd. Say a mentally absent old woman needs to find her husband (who’s, of course, dead). Holland has no problem taking the dough and “looking for him.”

These two winners are forced to team up and find “Alice,” a mysterious lookalike for the dead Suzy Shoemaker, and a semi-professional porn actress. Is it a coincidence that Suzy killed herself over a porn tape when there’s someone who looks exactly like her that does porn? That’s what these two need to find out.

Oh, and Suzy Shoemaker also happens to be the daughter of presidential hopeful David Shoemaker. All of a sudden, these suspicion crumbs are starting to look like they may belong to a freshly baked conspiracy scone.

To throw just one more wrench into this equation, March’s 14 year old overly-inquisitive daughter, Holly, wants to help. March knows this is a bad idea, but there are so many hip young folks involved in this mystery, that having a teenager around to do some undercover snooping may end up paying off.

Of course, you know if a 14 year old girl is getting involved in a case with dead people, that at some point said 14 year old girl is going to be in danger. So March and Healy aren’t just going to have to solve this case. They’re going to have to keep Holly safe, something that becomes harder and harder to do the deeper this mystery gets. And in case you’re wondering, it gets real deep!

Black (along with co-writer Bagarozzi) does what he does best. He puts a couple of flawed ill-matched individuals on a case together and allows them to equal-parts succeed and stumble their way to success. It’s what made Black one of the most successful screenplay writers ever.

But as we all know, this is one well-worn genre. The audience has seen it all. Therefore, if you want to succeed, you have to do more than follow a formula. And The Nice Guys separates itself from its competition in a couple of ways.

First off, this is Shane Black. He’s so fucking good at writing this kind of movie, that he stands out from everyone else just by showing up. Everything from the action to the dialogue is a level above. It’s funnier. It’s smarter. It’s better. Every other page we get a line like, “Marriage is buying a house for someone you hate.” Or, “If you had me ‘figured,’ jagoff, you’d start running – and you wouldn’t stop ‘til all the signs were in Spanish.”

Then there were the descriptions: “The Counter Girl is a punkish looking freak with pierced everything.”

We even get fun little moments that your average writer never thinks of. For example, you ever wonder where those stray bullets go? In a scene where Healy’s struggling to get away from the bad guys, he barely avoids a shot to the head. Instead of that being the end of it, we watch the bullet go out the window, across the street, and strike an unsuspecting woman at her window in the shoulder. She yelps and falls down out of frame. It was hilarious.

But just being the best at a genre isn’t enough. You should always be pushing yourself, looking for little angles to make your story different from any other “buddy cop” flick out there. Here, Black and Bagarozzi do this with Holly, March’s 14 year old daughter. I mean how many buddy cop movies have you seen where the cops are forced to lug a 14 year old girl around? Not many.

And it’s not just for show. You see, when you add an unknown element to a known situation, you get a new dynamic. Your cop duo can’t just hurl predictable insults at each other for 90 minutes. Healy has to be careful with what he says, since Holly’s always around. March has to stop every once in awhile and figure out how to keep Holly out of harm’s way.

There are even situations where March needs his daughter to get the job done (fitting in with a younger crowd to infiltrate a party). So his daughter temporarily becomes the most valuable commodity of the three, giving her the power, and shifting the dynamic, once again, to something that feels unfamiliar. Which is good! The last thing you want in a buddy-cop movie is brain-numbing familiarity.

Here’s the thing with The Nice Guys, though. It has a lot of moving parts. It’s basically like “The Other Guys,” but with a brain. And while that’s certainly nice (yay for movies that don’t pander!), it feels like it needs a simplicity pass. I couldn’t figure out, for the life of me, why Suzy Shoemaker’s aunt hired March to find Alice (the Suzy lookalike) in the first place. Did she think Alice was her niece? Did she just want to see a woman who looked like her niece? I don’t know.

And I know that information is in the script somewhere. But I had to process so much information, it slipped by me. This happens a lot. I’ll confusedly ask a writer, “Why did Ace want to double-cross Mary if he was in love with her?” And the writer, huffing and puffing, will animatedly respond with, “Did you even read the script!? The answer is on page 55 line 12. She gives him the copy of The Grapes of Wrath, which, if you remember, he read to her on page 12 in their childhood flashback, and she said, if you ever see this book again, it means I can never be with you.” Um, right.

The point is, the more complicated a plot is, the more hand-holding the reader needs. ESPECIALLY in the early-going, since that’s when the most new information is being thrown at the reader. Later, when we have all the names and relationships down, we can handle those details. But early on, it can be tough. So we need your help.

The only other issue I had is that it didn’t feel like there was enough conflict between Healy and March. This is always a sticky issue when you write a buddy-cop flick because, on the one hand, you don’t want to write another clichéd: two “cops” hate each other for no other reason than it leads to lots of conflict-fueled arguments!

But if you go away from this cliché, you run the risk of the relationship being bland. I mean sure, you can claim, “I didn’t do the cliché thing! Points for me!” But was it really worth it if we’re now bored by an uninspired relationship? I still haven’t figured out this balance. How does one write a genre where the very core rules of the genre are cliche, and then not make it cliche (I’d love to hear thoughts on this in the comments)?

Indeed, I felt like there was something left on the table between Healy and March. While they were definitely different characters, the longer the script went on, the more similar they felt. Maybe that’s because Black and Bagarozzi were looking to avoid the “clashing personalities” cliché. Maybe not. I don’t know. But I hope in subsequent drafts, they address it.

Anyway, regardless of its issues, The Nice Guys was a fun little script. Definitely worth reading. I mean, how can you say no to the newest/oldest Shane Black joint?

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Dialogue set ups and payoffs. Shane Black loves setups and payoffs. But he doesn’t only do it with his action. He’ll use the device in dialogue as well. This is a great way to get an easy laugh. For example, when March is forced to take Holly to a party to help them find Alice, they first walk in and see a bunch of sketchy characters. “Dad, there’s like, whores here and stuff.” March responds with, “Holly, how many times have I told you..? Don’t say, “and stuff.” Just say, “There are whores here.” Later on, Holly finds herself in a room watching porn with an overtly sexual redhead. Holly, working for her dad, casually asks the redhead if she’s seen Alice. “What’d she look like?” the redhead replies. “Well,” Holly says, “Sorta like that woman on TV, that kid’s show chick who died—“ “The one who just offed herself? That’s rad! She’s all, “remember kids, politeness counts,” meanwhile she’s like, doing anal and stuff.” Holly capitalizes on this: “Don’t say, “and stuff” – just say, “She’s doing anal.”

What I learned 2: What I’m about to tell you may be the most important advice you ever hear. Like, EVER, and stuff. I’m serious. Tape this to your wall. Tattoo it on your forehead. Ready? Never wait for this town (or for that matter, the world) to give you anything. If you want something, you will never have it unless you GO OUT AND GET IT. Black was in a downward slope in his career. If he would’ve kept writing scripts in his multi-million dollar basement, hoping for success again, I’m not sure we’d be hearing Black’s name today. Instead, he went out and MADE A MOVIE HIMSELF, which led to a relationship that would later turn him into one of the hottest directors in town. If I say it once, I’ll say it a thousand times: NEVER WAIT FOR ANYTHING. GO OUT AND GET IT.

Get Your Script Reviewed On Scriptshadow!: To submit your script for an Amateur Review, send in a PDF of your script, along with the title, genre, logline, and finally, something interesting about yourself and/or your script that you’d like us to post along with the script if reviewed. Use my submission address please: Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Remember that your script will be posted. If you’re nervous about the effects of a bad review, feel free to use an alias name and/or title. It’s a good idea to resubmit every couple of weeks so your submission stays near the top.

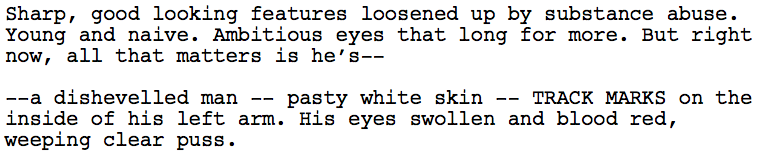

Genre: TV Pilot (Crime Drama)

Premise (from writer): An ambitious junkie and his severely traumatized war veteran sister, struggle with working for their manipulative crime boss father’s drug trafficking business.

Why You Should Read (from writer): The Sopranos meets Breaking Bad…. Could the bar be set any higher? Back in February when I uploaded Shrapnel to the Black List, it was ranked no. 2 overall on the monthly list. At its core, Shrapnel is about a brother and sister fighting their true identities trying to be people that they’re not in order to please those around them. Anyway, with the main goal of becoming a TV writer, the purpose of Shrapnel is to serve as a convincing staffing sample for similar genre/tone shows. It is not the most high concept of ideas and as a consequence I don’t expect to become the next Mickey Fisher with this project. I simply wrote the show that I want to watch. But concepts aside, the reason why we tune into our favourite shows each week is because of the characters, and hopefully the dried blood of my passion for the characters/story world is evident on the page.

Writer: Cameron Pattison

Details: 70 pages

Meth.

Need I say more?

It’s everywhere.

Who wouldn’t want to write about meth after watching one of the greatest shows in television history?

Bitch.

Not only that, but one of the best internet time wasters in the world is looking at those “Faces of Meth” sites. You see the user before meth and then after meth, and let me tell you. It’s the most entertainment you can have on your own outside of, well, doing meth!

But I got bad news for meth lovers. You don’t want to write about meth. Ever since Breaking Bad, half the pilots out there cover meth-dealing, heroin-dealing, or some other drug dealing. That’s the problem with chasing trends. You never know if you’re going to snatch onto the trend’s tail, or fall down on your face and watch it float away.

I’d go so far as to say Meth/Drug centered pilots are the pilot version of zombie specs. Everyone’s got one. And when everyone’s got one, there are only two ways to stand out. You have to find a unique angle that hasn’t been done before (meth addicted talking unicorns?) or you have to be an amazing writer who writes the shit out of your pilot. Let’s hope Cameron beats the odds and nails one of the two.

Shrapnel follows a rather informal narrative, jumping back and forth between different sets of characters in different situations. Our main character is Tommy Harris, a 20-something young man who lives in a small town where everyone’s struggling to pay the rent. The best way to keep a roof over your head in these parts is to… you got it… sell meth!

Tommy doesn’t want to do that. He’s got a nice thing going with his fiancé, Sarah, and despite his Drug Kingpin father, Vincent, pushing him to commit to the family meth business, you get the sense that Tommy wants to live an honest life.

Meanwhile we meet Rene, a 30-something lesbian military vet who’s in an even tougher situation than Tommy. She’s got a wife, Dani, and the two are trying to raise their 4 year-old son, Luke, despite Dani’s overbearing mother trying to gain custody of the child.

The two storylines each have their own twists. In a flash-forward at the beginning of the pilot, we see that Tommy’s killed Sarah for “the family.” We then jump back to a week earlier to figure out what led to this.

Rene and Dani are so broke they’re forced to live in a cheap hotel. It gets so bad that Rene pawns their wedding ring to pay for their room. But when Dani spots her wife ringless, she gets upset, so Rene goes about trying to get the ring back, eventually connecting with an old war buddy to steal it. As you’d expect, that doesn’t go well. At all.

There are other players involved. A young naïve kid, Chris, is working for Vincent. When he does something wrong, Vincent has him make up for it in the worst of ways. Then there’s a highway massacre where another meth-connected family mows down a group of cops.

There’s also the degenerate Mickey, Vince’s right-hand man, a soul so devoid of a moral compass, he’d probably skin a man alive if Vincent told him to.

In the end, we learn whether Tommy did, indeed, kill Sarah. We also reveal that Rene is Tommy’s sister and Vincent’s daughter, and that the only way she’s going to be able to provide for her wife and son is if she gets back into the family business, a move she’s been avoiding her entire adult life. I guess it’s true what they say. The family that draws breath together sells meth together.

I don’t know if Shrapnel’s a show. But Cameron sure is a good writer. Read the first scene of Shrapnel and I dare you not to keep reading. There’s a heavy atmospheric intensity to the way this man sees the world that makes you an audience member when you read him, not a critic.

Well, that’s not entirely true. Cause this site is about learning, I have to be critical, and while Shrapnel is, by and far, a strong sample, there were some things that didn’t quite click. Or, to use meth-speak, Shrapnel was only 70% purity.

My biggest issue is that if you didn’t tell me what the pilot was about beforehand, I’d have a hard time figuring out what the story was. Don’t get me wrong. The writing is stone cold impressive:

But as we jumped back and forth between Tommy, Sarah, Rene, Dani, Vincent, Chris, and Lou, I had a hard time keeping up with how it all fit together. And I get that that was the idea – we needed to keep reading to figure it out. But because I didn’t know how, specifically, Rene and Dani were involved with Tommy and Vincent, their story felt a little out of tune for me.

With Tommy, we get that opening scene which adds purpose to his storyline. We see his fiance dead, cut to a week earlier, and we see him with her, alive. Happy. Therefore as that story progresses, we have a reference point for what to look for.

I didn’t have that reference point with Rene and Dani.

You can sometimes pull that off if the “out in left field” storyline is compelling on its own merit, but the struggle of trying to get a job and retrieve a wedding ring didn’t quite do it for me. Without understanding these characters’ importance, I didn’t care if they succeeded or not.

One of the problems with writing “Traffic” narratives (multiple story threads that are happening independent of each other), is it’s a lot easier for the reader to get lost. A writer must ALWAYS take this into consideration so that they throw in the occasional reminder of what’s going on. I call it “holding the reader’s hand.” The higher the difficulty level of your story, the more you need to hold the reader’s hand throughout it.

Cause I needed that. I got lost. In one scene, Chris ends up sleeping with Sarah (Tommy’s fiance) while Vince videotapes it, and I guess all three parties were in on it. I couldn’t for the life of me figure out why anyone would do this, but it definitely felt like one of those “throw real-world logic out the window” situations. The audience always smells it when characters aren’t acting honestly, so the scenes never work. And I didn’t believe Sarah would fuck Chris under any circumstances.

As for Sharpnel as a TV show, here’s how I see it. The script definitely achieves what it sets out to do. Sopranos meets Breaking Bad is EXACTLY how I’d pitch this. And while Cameron isn’t David Chase or Vince Gilligan, he’s pretty darn good. This guy can make dirt sound exciting.

I’m just worried about the lack of a hook here (which he admits is a problem). Breaking Bad had a chemistry teacher who was forced to cook meth to save his family. Sopranos had a mobster with a therapist. Shrapnel needed something to stand out. I so often hear writers say what Cameron said up above. “I knew there was no hook but I just wanted to write it anyway.” You can FIND a hook, people, and still write the show that you want. It takes a little longer to figure it out, but it’s worth it. A hook ALWAYS gets you a leg up on the competition. And this is a competitive fucking industry so you need every leg up you can get.

Still, if you’re a producer looking to develop dark gritty TV ideas and need a writer, you’ll definitely want to sample Shrapnel. It’s one of the better amateur TV pilots I’ve come across.

Script link: Shrapnel

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: An “out in left field” plotline is a sub-plot that operates independently from the main plot. There’s zero crossover into the main plot until some point later in the story, when the two plots finally intersect. Father Karras’ sub-plot in The Exorcist is an “out in left field” plotline. The idea behind this device is to create a dramatic curiosity in how this “isolated” storyline is going to connect to our “central” storyline. The problem with these, though, is that if they’re not great, audiences tire of them quickly. They become impatient with the fact that they don’t seem to have anything to do with our movie/show. I didn’t think Shrapnel’s “out in left field” Rene storyline was bad, as the characters involved were strong. But the storyline itself didn’t interest me, and I turned on it as a result. So my advice with these, is, if you’re going to write them, make sure they’re an excellent standalone story. They have to work on their own. That way, even if we can’t figure out how they connect with our main plot, we’re still enjoying ourselves.