Genre: Thriller

Premise: After nearly dying in a car accident, a mechanic is given an experimental drug while in a coma. When he awakes, his IQ begins to skyrocket.

About: This is not the first Eric Heisserer/Ted Chiang collaboration. For those of you who get the newsletter, you’ll remember when I reviewed their previous collaboration, Story of Your Life (about an alien visitation that requires a linguist to help communicate with the ETs). The project has since secured Amy Adams for the lead role (she’s perfect) and Denis Villeneuve to direct. You may know Villeneuve as the director of another big spec script, Prisoners. Heisserer previously wrote The Thing remake and Final Destination 5. He’s since moved into directing, last year helming the Hurricane Katrina thriller, Hours, which starred Paul Walker.

Writer: Eric Heisserer (based on the short story by Ted Chiang)

Details: 116 pages (undated)

One of my favorite scripts from the last couple of years is Story Of Your Life. It took a big idea and approached it from a very intimate place. Sort of like M. Night’s “Signs,” but way better (and more original). As a screenwriter, this strategy is one of the best ways to get noticed, as you’re giving producers two things they want – a big concept and a story that can be shot on a reasonable budget.

But they’re not easy to write. Because of the tiny scope, the writer often ends up running out of engaging material. Look no further than one of the WORST movies I’ve seen this year, 2008’s Pontypoole (caught it on Netflix). It’s about a zombie outbreak that takes place entirely inside a radio DJ booth. Somewhere around minute 30, they ran out of stuff to do, and the rest was just, well, awful (they eventually figure out that the zombie outbreak is spread though…VOICE! So just by talking, the DJ is spreading the zombie virus! I’m not kidding!).

If you can prove yourself in that realm (your movie actually gets made), that’s when the gatekeepers trust you with a bigger budget. Which leads us to today’s script, the oddly titled, “Understand.”

30-something David Miller is a lowly car mechanic who, you get the feeling, hasn’t ended up where he thought he would. The one thing he’s got going for him is his beautiful wife, Lauren. One day after work, he picks her up and the two drive home like they always do.

Except before they get there, they get rear-ended into an icy river, where poor David watches his wife drift away. Three months later, David wakes up in a hospital room from a coma. He’s been told by his doctor that in order to get him out of the coma, they had to use an experimental drug.

As the days pass, David starts to feel smarter and starts craving knowledge. But this newfound intelligence comes with a price. The doctors won’t let David leave. Whatever this drug they injected him with is, it’s less about helping him and more about making him their lab rat.

The great thing about being super-smart though, is that you can outsmart the dumbos. And David’s able to escape with minimal effort. Once out in the wild, his intelligence continues to grow, allowing him to do things like learn Taekwando in the time it takes to check your e-mail and fly a Cessna plane with a three-minute prep course.

David quickly realizes why the doctors wanted to watch him so closely. David isn’t just becoming smart. He’s becoming a weapon.

Soon, David learns of a previous recipient of the drug he was given, another escapee named Vincent, who is a month ahead of him in the trials. Being one month ahead means having 30 additional days of intelligence growth. David may be a genius. But Vincent is the equivalent of 20 geniuses. David’s purpose shifts from eluding his pursuers (which now include the FBI) to stopping Vincent, who appears to be prepping an attack that could be the precursor to the end of the world as we know it.

“Understand” is a unique and entertaining piece of material. It’s sort of like Limitless meets The Bourne Identity meets Transcendence meets The Matrix meets Highlander. If there’s a hiccup in the script, it’s just that – it may be trying to do too many things.

For me, the script seemed to set itself up as an intimate thriller, possibly something that took place entirely in the hospital. Then, seemingly out of nowhere, it becomes a traditional “man on the run” Liam Neeson vehicle. It was during this section that I began to lose interest, since we’ve seen a bajillion of these thrillers already. The fact that the rapid-intelligence thing had been done fairly recently in Limitless didn’t help either.

But then Chiang and Heisserer start to get trippy, with David’s intelligence becoming so advanced that he can actually calculate where bullets are going to go before they’re shot, allowing him to dodge them (or, in some instances, deflect them with a knife blade).

However, once Vincent (the other super-smart guy) becomes David’s nemesis, the script almost becomes a super-hero movie, with the two fighting on top of buildings with super-advanced sparring skills. Heck, they eventually get so smart that they can move things with their minds, throwing yet another influence, Star Wars, into the mix.

What’s happening here is not a unique problem. Sometimes, for a reader to buy into a world, it requires the writer to slowly take us through the steps. In other words, it would be stupid if David could use telekinesis right away. But after we’ve seen him “level up” several times, it makes sense.

But if you take too long before introducing the REAL story (in this case, the emergence of Vincent and his diabolical plan), the reader can become confused. Oh, they say, I thought this was about a guy running away from the government. But it’s actually about a battle between two genius super-heroes.

The thing is, I mostly run into this problem with inexperienced writers who haven’t yet learned how to keep a consistent plot thread going for an entire script. They want to throw in new bells and whistles to keep your interest, not realizing that each one takes us further away from the original story we thought we were reading.

That’s not the problem with Eric’s script. He still knows what he’s doing so he makes it work. I just thought it felt a little unbalanced, with Vincent becoming this huge story agitator too late in the game.

The only other major observation I had was David’s job. David is a mechanic, which I thought was an odd choice since it had nothing to do with the story. There was ONE major payoff of him being a mechanic (he disabled the bad guy’s car), but if David is as smart as we’re led to believe, he should’ve been able to figure this out anyway.

We writers do this a lot. We absolutely LOVE a good payoff. But sometimes we love them so much that we’ll keep the setup to that payoff even if changing it would improve everything else in the screenplay BUT that payoff.

So say I was writing a comedy about an airplane pilot who can’t tell a lie for one day. The reason I made my main character a pilot? It’s a setup to an awesome payoff late in the script where my hero escapes the bad guys by hijacking a plane! Sure, that’s a nice payoff, but if I made my character, say, a lawyer instead, the setup would be a lot more ironic and lead to ton more funny scenes (Liar Liar). So you have to ask yourself, is keeping your main character a pilot so you can have that plane hijack scene really worth it?

I don’t think David being a mechanic is milking the irony of the situation enough. Flowers for Algernon (another “turn to genius” story) made its main character mentally retarded so that the irony level was high when he became smart. I don’t think that’s right for this particular script, but maybe they could do what Good Will Hunting did and make David a low level worker at a place known for the high intelligence level of its employees, like a giant bank or a huge trading firm.

By no means is going with a mechanic a bad choice. I just think if you can milk the irony of a concept, you do it. As a screenwriter, you don’t want to leave any stone unturned when you write a script. Always try to get the best out of every single element.

Anyway, “Understand” was a little schizophrenic but extremely well-written and moved at a speed-train like pace. The weird second half turn did throw me, but it also kept me off-balance, so I didn’t know what would happen next. I’d recommend this one if you can find it!

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

Number of times I checked the internet during read: 7

What I learned: Ahhh, I do not like numbered montages.

1) Frank works at his desk.

2) Frank and Sara sit at home, reading.

3) Frank goes fishing with his buddies.

4) Frank back at his desk, working.

I’m a big believer in keeping the writing as invisible as possible. The idea is to make someone forget they’re reading so they’re always immersed in your story. Anything you do to disrupt that reminds them it’s just a big fake made-up story. So seeing montages (long ones at that) that were numbered here, took me out of the screenplay. I was more focused on the “shot number” than the images themselves. With that said, Eric may be directing this or writing it for a director. In that case, maybe he wanted to know the specific shots he would have to get.

Genre: TV Pilot – Drama

Premise: The son of an Arab dictator, Barry has fled his past and built a life in the United States. But when his father calls him back for his nephew’s wedding, he will ask Barry to come back into the family.

About: This upcoming FX show has a complicated backstory. The Hollywood Reporter did a wonderful piece on it recently that gets into a lot of the details. Basically, the guys behind Showtime’s breakout show, Homeland, went to market with their next project, Tyrant, and started a bidding war with FX winning due to an on-air commitment. Since then, the writing team, Howard Gordon and Gideon Raff, have split up, due to disagreements over the show’s direction, that eventually led to Raff (the less experienced of the two) leaving. This seems to go back even further, as Raff is the one who came up with Homeland, but had zero day-to-day involvement with the show itself, which, it’s implied, Gordon resented.

Writer: Gideon Raff (executive produced by Howard Gordon, Craig Wright and Gideon Raff)

Details: 68 pages – November 27, 2012

After reading that Hollywood Reporter piece, I was wondering if I could read this pilot objectively. On the one hand, it sounds like they’d repurposed the show seven times before it finally hit the cameras, then added two more for good measure! So you’re thinking, there must have been a lot wrong with it.

On the other hand, you’re rooting for the underdog tale of the little show that could. Tyrant has so many things working against it – the biggest of which is, will an American audience care about a show centering around a Middle Eastern family? – that you can’t help but hope that it beats the odds and succeeds.

Of course, the terrifying reality of the entertainment business is that the bored consumer who’s just jostled through a 14-hour work day and put the kids to bed, doesn’t give a shit about how your show (or movie) came to be. They could care less that you had Ang Lee and lost him, or that the show had to be moved to five different countries to shoot. All they care about is if it’s a good show or not. Well, if they stay close to the pilot draft I just read, Tyrant isn’t going to be good. It’s going to be great.

40 year-old Barry is a struggling optometrist who works out of a ratty mini-mall in Orlando. Barry has a secret though. His family runs the country of Asima (a fictional stand-in for a Middle Eastern country), and are some of the richest people in the world. You get the feeling that if Barry left that life for this one? There’s gotta be a damn good story there.

Barry’s married to an American woman, Molly, and has two teenagers, the artsy 17 year-old Emma and the excitable 15 year-old Sammy. Unfortunately for Barry, his brother’s son, who lives back in Asima, is getting married, and even Barry, with his myriad of excuses, can’t get out of this one.

So he and the family fly to Asima where they meet the family Barry grew up with. There’s the father and president/dictator of the country, Hassan. Then there’s Barry’s older evil brother, Jamal. The Ferrari-driving philandering Jamal is probably the most evil person you’ll ever see on TV – he rapes underage women with guards in the room to make sure he’s not attacked, he molests his son’s fiancée, and he orders death to anyone who opposes him.

It’s clear Jamal doesn’t want Barry here, which is fine by Barry, ’cause he wants to get out of Asima as soon as possible.

Barry’s son, Sammy, however, can’t get enough of Asima. Instead of living in the strip-mall dominated middle-class suburbs, he’s hanging out in a palace! Not only that, but the brash, confident Jamal is everything Sammy wished his own father could be, and he immediately sees him as a role model. Oh, but Sammy has a secret. He’s gay. And in a world where homosexuality is punishable by death, maybe staying in Asima isn’t the best idea.

I think we all see where this is going. Barry’s father unexpectedly falls ill, and the family has no choice but to discuss who gets the throne once he dies. Everyone assumes it’ll be Jamal, of course, but Hassan shocks everyone when he says he wants Barry to succeed him. Barry wants nothing to do with leading this corrupt country, though. He wanted to get out of here yesterday. The problem is, it may not be up to him anymore.

Okay, let’s just get something out of the way first. This IS The Godfather, the Arab version. We have a wedding, we have a dying leader. A reluctant heir is chosen. I mean, it’s not a beat for beat remake or anything. But it’s the same auditorium with the seats rearranged. The thing is, it didn’t matter. Because it was awesome.

When you’re talking about TV shows, you’re talking about interpersonal conflict – conflict between characters. Since you don’t have the advantage feature films have (huge exterior conflicts to drive the drama like reptilian giants, robots, Loki, Apes), the best way to keep the drama flowing is via conflict between characters.

For that reason, you want one main heavy conflict duo you can keep coming back to. In Breaking Bad, it’s Walter White and Jesse Pinkman. Here, it’s Barry and his brother, Jamal. Not only is Jamal the most evil person in existence, but he has a completely different idea of how to rule the country from Barry. Barry wants to rule through diplomacy. Jamal wants to rule through terror. On top of that, you have a deep history between the two and you have their basic sibling rivalry. As a result, every scene they’re in together is potent.

Speaking of Barry, I loved the complication behind his character. See, when you write a character, you don’t want to craft him too heavily in one direction. Well-constructed characters are complicated. They have other sides to them than the side they generally show the world.

(spoiler) In Tyrant, there’s a series of flashbacks of Barry and Jamal as children. Jamal is athletic and tough. Barry is nerdy and withdrawn. In the pilot’s final scene, their father wants a seemingly innocent man killed, and he asks Young Jamal to do it. Young Jamal points the gun, but he’s too scared to pull the trigger and runs away. As the father goes to deal with this, Young Barry picks up the gun and shoots the man five times. Barry may be against the way his father rules the country, but when he’s called upon to make complicated decisions, he delivers.

Now, since we know that Barry has the capacity to be bad, there’s an unpredictability to him that’s exciting. I think it’s always more interesting if we’re not sure what a character is going to do from situation to situation. Think about it. How boring is it if a character always does the right thing? Or always does the wrong thing? It’s when you’re unsure that the scene is truly charged. Pay attention to “The Governor” in Seasons 3 and 4 of The Walking Dead to see how effective this approach can be.

I’m not sure what this says about Jamal though. This guy is so over-the-top bad and if there’s one criticism I had with the screenplay, it’s that Jamal is so two-dimensional. I’m betting that this is one of the first things they addressed moving forward though.

Another thing Tyrant did well was it made sure there were a lot of memorable moments in the pilot. It’s rare that I see one inventive or original scene in a pilot these days – something you truly haven’t seen before, but Tyrant had 5-6 of them. (spoilers) There was the bite-off-dick scene, the molestation of the daughter-in-law scene, the Young Barry shoots a man dead scene. Raff was not afraid to push the boundaries and write some pretty boundary-pushing stuff.

In another great scene, Barry’s family gets on the their plane to go to Asima, only to find out it’s completely deserted. Barry learns that his brother has bought up every seat on the plane for them. Sammy is thrilled. He flops down in first class, thinking this is the greatest thing ever. What does Barry do? He heads right back to seat 18c in Coach, the seat he was assigned to.

That’s what really sets Tyrant apart. Not only was this a memorable scene, but it used the scene to TELL YOU ABOUT THE CHARACTERS. By staying in his assigned Coach seat, Barry shows us how much disdain he has for his family and the way they go about things. Whereas by showing Sammy take a first class seat, we know he will be susceptible to the excesses of his grandfather’s family.

Will all this mean a big hit? I don’t know. I don’t know how much Gordon has changed the script. And we still don’t know if an American audience will care to watch a show about an Arab family. But I sure hope they do. This series has the potential to be a classic. Without a doubt, I’ll be checking it out when it airs. This is the most excited I’ve been for a TV series in forever.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: When you write a TV pilot, you’re trying to set up as many little threads of conflict as you possibly can, so that the people watching the show will want to tune in week after week to see how those conflicts play out. If you don’t set up any threads of conflict, nobody will care about your show. Nobody will want to see the next episode. I guarantee it. So here, we have the base conflict between Barry and Jamal. We have conflict between Barry and his son (who doesn’t like his father’s style of ruling). We have conflict between Barry and the country he’s ruling. We have conflict with Sammy being gay, and how dangerous being gay is in this country. Barry’s daughter hates the country and doesn’t want to be here. Barry has a former girlfriend he still holds a candle for who’s now married to Jamal. Barry’s wife finds out about this, setting up a conflict between these two women. Probably the biggest conflict of all will be between Barry and himself. Much like how Walter White struggled with his moral compass as a drug dealer/family man, Barry will struggle with all the morally questionable decisions he’ll have to make as a dictator. You look at the future of this show and it’s just drowning in unresolved conflict, which is exactly the way you want it to be.

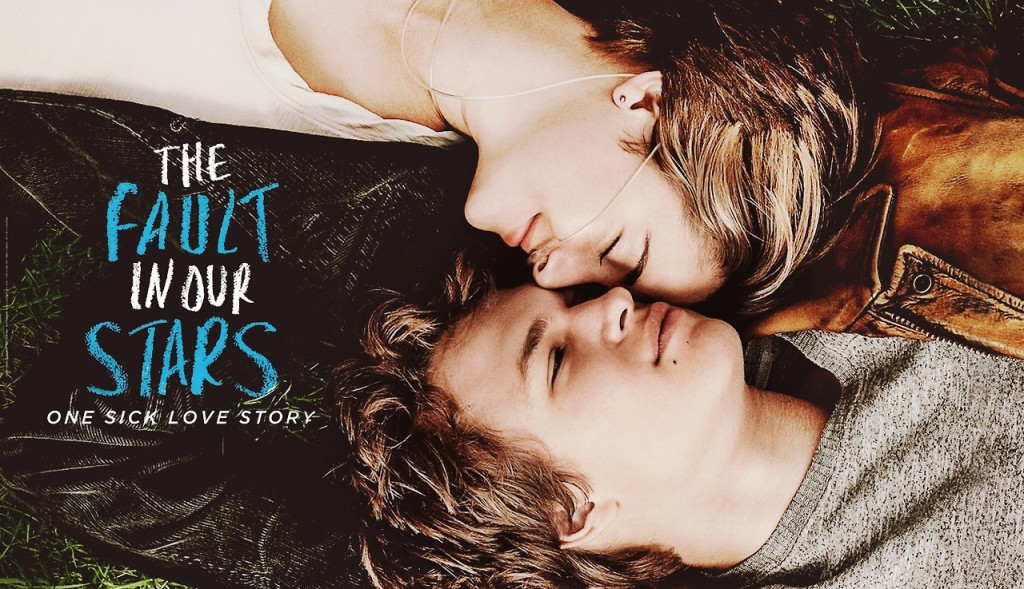

It’s Monday morning and the talk of the town is how a little movie about cancer kids beat Tom Cruise in the middle of Blockbuster Season. The little film that could (The Fault In Our Stars) grossed 48 million to Tommy Boy’s (Edge of Tomorrow) paltry 28 million. That’s not just a beating. That’s a slaughter. Twenty years ago – heck, even ten years ago – this never would’ve happened. So why is it happening now? Anybody who tells you they know for sure is a liar. And I don’t know either. But what’s so interesting about this particular battle is that there are a ton of factors involved. And they’re all so damn juicy that I can’t wait to get to them!

1) Is Tom Cruise a movie star anymore?

If you’re going to put your money on one horse for Tomorrow’s lackluster showing, it’s probably that Cruise isn’t a movie star anymore. His last three films (Oblivion, Jack Reacher, Rock of Ages) failed to hit 100 million here in the States. Whether this has to do with Cruise getting older, Cruise going through his crazy streak, or people just losing interest in the actor isn’t clear. But it’s looking like his glory days are over. The question is, is this representative of a much larger trend?

2) Is the movie star dead?

As people stood on the hilltops and claimed the death of the movie star these last few years, I didn’t buy it. But a look at this year’s crop of summer films says otherwise. From X-Men to Godzilla to Spider-Man 2 to Rise of the Apes. The star in all these movies is the property. The owners of these properties then plug in the casting holes with whomever they deem worthy. You’re seeing less and less movies being made like Die Hard, where the star’s the star. With that being said, this is mostly (at least for now) a symptom of the summer season. As we get into the last quarter of the year and ACTING is actually required to make the movie good, movie stars are needed. How long that lasts, we will have to see.

3) Was the concept too weird?

Even though I loved the script for Tomorrow, the one thing I worried about was whether a mass audience would buy into the concept. I get nervous when you mash two big ideas into a single film, because, typically, audiences will only buy into one. They can accept aliens invading. They can accept time-travel. But can they accept an alien time-travel movie? I’m still not sure.

4) The title sucked.

I don’t talk about movie titles much because it’s one of the most objective parts of the business. But if Hollywood isn’t given a property that already has a name, they almost always fuck it up. “Edge of Tomorrow??” What the hell does that even mean?? It’s the most generic title ever and reeks of compromise. Edge of Tomorrow dudes, let me help you out here. When you have a property that nobody knows about and you’re trying to compete against properties (X-Men, Spider-Man) that have been around for decades?? You don’t want a title that’s going to make you MORE invisible. You have to take a chance and use something that stands out. The script’s original title, “All You Need Is Kill,” would’ve been so much better. It’s way edgier, and probably would’ve brought in more of the key demo you wanted – teenagers.

5) Does this fuck things up even further for spec writers?

While “All You Need is Kill” was based on a graphic novel, for the most part, it was a spec script. Nobody knew about the graphic novel. And it was written on spec (and sold for a million bucks). With the failures of high-profile specs this year like Transcendence, Draft Day and now, to a lesser extent, Edge of Tomorrow, is Hollywood going to be further terrified of betting on non-IP? Also, if the movie star system is dead, what are screenwriters supposed to write about now? It used to be, write a male lead inside a marketable genre. If that’s gone, and the studios are only dealing with high-profile IP anyway, then what’s the strategy of the average screenwriter? Should he even write original material anymore? Will it be like TV used to be, where you write a spec episode of your favorite show? So writers would write a feature in a long-standing franchise, like X-Men or Batman, in order to break in? Probably not, but it’s not clear where this is going yet. So we’ll need time to figure it out.

6) Did Fault really win the weekend?

Ah-ha, now we get to the part of the box office that the media still hasn’t figured out yet. Fault did beat Tomorrow at the domestic box office, but it’s not going to come anywhere NEAR Tomorrow internationally. Tomorrow has already racked up 80 million dollars internationally, putting it at 110 worldwide. When it’s all said and done, it should make close to 300 million. Fault will be lucky to make half that. The thing is, for the last 20 years, the media has put so much focus on domestic, they still think that’s the race to talk about. They understand that race. But movies make more overseas now than they do at home. Sometimes a hell of a lot more. But how do you write that definitive worldwide box office column when one of the key movies hasn’t even hit all of the available territories? It’s kind of a confusing byline (“Edge of Tomorrow maybe won the world box office this weekend…as it was in 65% of the territories but hasn’t hit the major European circuit yet and still hasn’t bowed in Peru, where Tom Cruise is enormous” doesn’t have the same ring to it as “Shailene takes down Tom!”). Since the domestic box office is definitive, I’m guessing they’ll continue to use it in stories. But at some point, this has to change.

7) People still read?

Probably one of the most confusing things about the modern-day box office is this whole reading thing. Studio heads, executives and producers claim the sky is falling because young people don’t want to spend two hours to see movies anymore when they can play on the internet, watch all that awesome TV, and play video games. It sure sounds logical, except that one of Hollywood’s biggest sources of income over the last 15 years has been book series adaptations. Harry Potter, Twilight, Hunger Games, Divergent, now Fault in our Stars. Movies are becoming antiquated but people still have time to engross themselves in a 2000 year old medium for 10 hours a story? Clearly, if people are spending that much time reading to the tune of adding billions of dollars to the box office, producers can’t bitch that it’s getting too hard to compete for people’s time.

8) Cancer curse.

Hollywood is TERRIFIED of cancer. People don’t want to be reminded of death when they go to the movies. They generally want to be happy. They want to be reminded of why life’s awesome. So how did Fault in Our Stars overcome that prejudice? Well, partly because it IS a movie about life’s awesomeness. The characters here have a lot of fun together. It goes to some dark places, but for the most part, there’s lots of positive energy here. The reason it beat the curse though is because it’s a really well-told story. It’s got a nice narrative drive (with the Amsterdam goal) and the characters rarely do or say the obvious thing, which gave it a fresh feel. The thing is, it was able to prove this in book form first, so people already knew it was good. I’d go so far as to say this wouldn’t have made 10 million opening weekend if it wasn’t a book first. I’ll say this though. I’ve never seen a movie this aggressively market itself as a cancer flick and do so well.

9) Tomorrow is good!

The big tragedy here is that Edge of Tomorrow is a really good movie! Not that I can say that myself yet (I was home sick all weekend), but a dozen site readers e-mailed me to say it was awesome, some going so far as to say it was the best movie they’ve seen all year. Usually, when a movie’s good, even if it doesn’t open well, it’ll make up for it with a long healthy run. But Edge of Tomorrow is planted right smack dab in the middle of the Summer Season, where even monstrous movies can disappear on their second weekend. Then again, it’s only real demographic competition the next two weeks is 22 Jump Street and Jersey Boys, and neither of those films directly crosses over with Tomorrow. So let’s hope that word-of-mouth spreads and the movie rebounds. If not, it might be the fault in Tom Cruise’s star.

Get Your Script Reviewed On Scriptshadow!: To submit your script for an Amateur Review, send in a PDF of your script, along with the title, genre, logline, and finally, something interesting about yourself and/or your script that you’d like us to post along with the script if reviewed. Use my submission address please: Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Remember that your script will be posted. If you’re nervous about the effects of a bad review, feel free to use an alias name and/or title. It’s a good idea to resubmit every couple of weeks so your submission stays near the top.

Genre: Buddy cop/Action

Premise (from writer): A maimed EOD Technician turned L.A.P.D. detective must work with a troubled young cop in order to bring down a team of cyber terrorists masquerading as Pharmacy thieves.

Why You Should Read (from writers): Do you wish TRUE DETECTIVE was still airing on HBO? Do you fondly remember the end of the 80′s and the little gem that was Lethal Weapon? Do you crave the perfect blend of action, plot, characters, and jokes? Of course you do!

“Down to the Wire” is a 21st century take on the genre, set to revive your hopes and trigger your nostalgia. This script has been polished with a particular focus on lean, realistic dialogue. The pacing is brisk, the jokes land, and the characters are fleshed out. One of the authors recently placed in the top 15 of the Sheldon Turner Writers Store Contest. Thanks for your consideration!

Writers: Byron Burton & Chris Mulligan Murray

Details: 113 pages

I want to talk a little bit about loglines before we get started. Loglines are tricky. First of all, a logline’s quality is limited to the story it’s summarizing. If your concept isn’t compelling enough, nothing you do with the logline will work.

With that said, not every story is “logline friendly.” There are some concepts that are perfect for the logline universe, like Liar Liar. And there are others that aren’t, like Dallas Buyers Club. Sometimes, the concept is so un-logline-friendly that your only shot at creating an interesting logline is to highlight the most unique aspects of your story and slap a summary around them.

The thing is, you want to avoid that if at all possible. One of the biggest contributors to logline confusion is irrelevant details, which is kind of what I’m seeing here. A “maimed EOD Technician” for example. How does that connect to two cops “bringing down a team of cyber terrorists masquerading as pharmacy thieves?” Whether he’s a maimed bomb technician or not doesn’t seem to matter in this particular case.

Now if you said a “maimed EOD Technician turned cop” had to take down “a group of local terrorists using car bombs to wreak terror,” there’d be a connection. Or if you said an “old school cop who shuns technology” had to take down a group of “cyber terrorists,” there’d be a connection. Or if you said an “ex-junkie pharmaceutical rep turned cop” had to take down “a group of cyber-terrorists masquerading as pharmacy thieves,” there’d be a connection.

But I don’t see how being in Afghanistan as an EOD tech has any connection to a case about pharmaceuticals. So something feels off about the setup. I’m not saying it can’t work. Maybe this just needs more room to explain. But it did make me worried. Let’s see if I’m getting all bent out of shape over nothing.

“Down to the Wire” follows Travis Boots, a former bomb tech in Afghanistan. Think Jeremy Renner in The Hurt Locker. After a bomb kills a local girl and six other soldiers, Boots is sent back home with a prosthetic foot and the knowledge that he has a brain aneurysm that could burst at any moment. I guess that makes Boots a walking time bomb.

Strangely enough, this gives Boots a carefree attitude that he takes all the way to the local police force. It’s there where he teams up with Joe Durmont, an alcoholic cop with very little initiative. Boots instills a brash unorthodox approach to their crime-fighting ways and pretty soon, they’re getting into all sorts of trouble.

Eventually, they make their way onto the hot case in the city. A team of thieves have been hitting pharmacies all over town, stealing thousands of dollars worth of pills. A charged up Boots believes that a recent overdose at the hospital is tied to the case and pursues the potential suspect.

But just when they have him in their grasp, he’s shot and killed by a sniper from afar, letting the two know that this case goes deeper than they suspected. They eventually catch up with the crew responsible and learn that the pills are a front – that the real crime is the customer database at all these pharmacies. But by that time, it’s too late. The baddies have caught Boots and Joe with plans of killing them. Will the duo make it out alive? Or will they be taking the world’s strongest sleeping pill?

I can see why “Wire” was picked. A lot of you read the first scene to see if the writer has chops and this has a very strong first scene. We’re in a war zone. There’s a bomb ticking away. There’s a little girl in the middle of it. A huge decision needs to be made: kill the girl or keep trying to defuse the bomb. It’s an intense harrowing opening. Kudos to Byron and Chris for writing it!

The thing is, after that scene, my fears were realized. I couldn’t figure out why it was so important for our main character to have previously been a bomb technician in Afghanistan. What did it have to do with any part of the story? He ended up with a prosthetic foot, but that didn’t come into play at all. He had a brain aneurysm, but that didn’t seem to come from the bomb incident. So why was he a bomb tech? Why was he a soldier at all?

If your main character has an extensive backstory, it has to play into the story somehow. For example, if I wrote Gravity, I wouldn’t give Sandra Bullock a long botany backstory. I suppose there’s some interesting juxtaposition between gardening and space shuttle repair, but because it doesn’t play into the story (in either a direct or ironic way), I wouldn’t use it. And that’s how I felt here.

I was also hoping for a lot more from the pharmaceutical storyline. My big worry going in was that stealing pills was going to be too small. There’s something almost impotent about it. I mean, when the bad guys rob a bank in a movie, they’re stealing everybody else’s hard-earned money. That’s why we get so mad. When these guys steal pills, all I thought was, “Well, they’ll just send more pills.” The pharmaceutical companies are billion dollar businesses. Who cares if they lose 10 grand worth of Adderall?

I wanted the pills to lead to something bigger early on, which would lead to something bigger, and eventually bigger. Instead, we find out at the end that the pills were a front for stealing personal information. Again, that’s a really tiny reveal. From my understanding, the thieves hit 6 pharmacies. Let’s say in each of those pharmacy computers there were 5000 names. So these people now have the personal information of 30,000 people. That doesn’t scare me at night. That sounds like the kind of thing that would be straightened out in a few days. Plus, I don’t know who these people are, so why should I care about them?

Basically, this comes down to a lack of stakes. They aren’t big enough. Not only did the pharmaceutical robberies feel low-priority for a typical Los Angeles police department, but I wasn’t sure what Boots and Joe got out of solving the case. Joe had just gotten a promotion. So it’s not like this was going to get him anything more. And Boots didn’t seem to have anything he wanted. He was just doing this because. I think in real life, that makes sense. You do something because it’s your job. But in the movie-world, audiences want to know why this case is so important to you because it’s the case they’re spending 2 hours of their life watching.

I like that Byron and Chris tried to do something with their characters. Boots could die at any moment, so he was a little unorthodox and crazy. And Joe was an alcoholic with a dementia-ridden mother (though I found it strange that his mom was 55 years older than him). The thing is, I felt like we could’ve done more. If Byron really could die at any second, then you have to go crazy with him. You have to have unbridled no-holds-barred fun with him. As of now, he’s operating at 70%. And we’ve seen the alcoholism and dementia-mother thing before. I read that stuff all the time in screenplays. You have to find something unique to each character. You can’t just copy and paste stuff from other characters you’ve seen and expect it to work.

If I were Byron and Chris, I’d think BIGGER. BIGGER BIGGER BIGGER. This is the MOVIES! When you’re thinking about the problem that would challenge your protagonist cops, you want it to be the kind of problem that would be on the FRONT PAGE of the newspaper for a week straight. I see pharmacy robberies being buried somewhere on page 5 or 6. Now if the pharmacy robberies escalated quickly and the bad guys’ plan kept getting bigger and bigger every 20 pages, that’s a different story. I’d love to see that. But that didn’t happen here.

I know Byron is a hard working writer who’s really in to getting better. So help him out. Read “Wire,” and give him some constructive criticism. I’m sure you guys can think of some ways to beef up the story. Good luck to Byron and Chris and thanks for letting me read your script!

Screenplay link: Down To The Wire

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

Number of times I checked the internet: 14

What I learned: Plot ingenuity. When you’re talking about an age-old genre, plot ingenuity becomes key. You’re already dealing with a generic setup (two cops forced together on a case), so a generic execution is a death sentence for your screenplay. That was one of the problems here. The execution was by-the-numbers. There weren’t any surprises until the very end. You have to take some chances and play around with the plot in these scenarios or else your script is going to look like every other cookie-cutter buddy cop procedural (or whatever genre it is you’re writing). Twists, turns, escalations, reversals, surprises, unique scenarios, imagination. Do more with the plot!

Carson here. Been feeling lousy all week, therefore I am, sadly, going to take a sick day today. Luckily I still have something to post. The other day when I was talking about the age-old screenwriting question of which kind of script you should write (something personal or something commercial), commenter Tom gave the best answer to the question I think I’ve ever seen. So I’m re-publishing the comment below. — I like the idea of rewarding good comments so I’m thinking of making this a possible monthly thing. Publish the 3-5 best comments of the month. Thoughts?

From Commenter Tom:

The question of “commercial vs. personal” is not black and white. There’s a Goldilocks zone to it, and it’s one that some writers never reach. Ultimately, there’s an artistic side to your brain and a mathematical side to your brain, and unless you have unbridled raw talent, you have to find a way to get Pappa Bear and Mama Bear to play together.

I see a common progression in amateur writers.

1. The Sum Is GREATER than the Parts

Many writers start out with personal, artistic projects. Stories about their life experiences, or their high school friends, or some small article they read that sparked their imagination. And the scripts? Unreadable. The dialogue is stilted, the scenes are cliche, the conflict and pacing is scattershot. These scripts suck. But there’s an undeniable heart at the core of them. Although the individual components suck ass, there’s a purity to the overall story. But no one can bare to read more than 10 pages.

The writer then retreats. He/she reads other scripts, modeling the voices of those writers. They buy copies of Save The Cat and Story. They follow the industry and see what kind of scripts are selling, modeling their next effort on some of the trends. They log line, beat sheet, and outline. The result is:

2. The Sum Is LESS than the Parts.

Welcome to 95% of the Amateur Friday entries. Each individual scene is adequate, perhaps even exemplary. Dialogue is clean. Characters have flaws. Act I turning point hits exactly on page 25. The lead is a 35 year old male who has a mentor, a love interest, and a cat that he saves on page 4. The concept, while not “blow your mind” is solid. Yet, these scripts are… soulless. It’s all calculation. Commercial, yes. But forgettable.

A lot of writers never leave this stage. They marvel at how easily their early scripts flowed, and they can’t seem to replicate that old creative vision. Every time they start setting a script in an early period, or with a female lead they block themselves. These writers, while not hitting home runs, get a few singles or doubles. They get repped by baby managers who have them submit 10 log lines a week to determine their next project. They get stuck in this mathematical, calculating style of writing. Their projects never gain traction.

But after some time in this zone, a few finally say “Fuck it. I’m going to write what I want.”

3. The Goldilocks Zone

These are the writers who finally get noticed. The commercial side of their brain is no longer boxing out the creative side. The stories are personal, but with a larger, worldly-accessible twist. The story flows naturally, and yet subconsciously matches up with the 3-act structure.

The time spent in Zone 2 was invaluable because now they know and understand structure. They know how to bottle Blake Snyder and put him on a shelf, away from the process, but always ready to help. They can step back and see their story not as disassociated gears on a clock, but as a full living organism.

And the real key is they LIKE the stories they’re writing.

The Zone 1 scripts were hard to read. The Zone 2 scripts were hard to write. But these Goldilocks scripts are fun. And as a result, the writer’s voice begins to seep into the pages.

That’s the balance all writers have to find. You MUST know structure. You MUST know what’s commercial. You MUST be able to forget it all.