Search Results for: girl on the train

Genre: Comedy

Premise: A womanizing man wakes up without his penis, only to learn that it’s taken human form and is determined to make his life miserable.

About: Deadline Hollywood’s already done the dirty work so I’ll let Miss Finke summarize it for you. “Morgan Creek bought Step Dawg, a comic script by Jeff Tetreault about a 30-ish man who returns home to discover that his single mom plans to marry his former high school stoner best friend. WME sold the script with Energy Entertainment. It’s the second script, but first sale for Tetreault. His first effort was widely admired, but didn’t sell because of obvious complications. Called Me and My Penis, the comedy focused on a womanizing man who awakens to discover his penis has gone AWOL and refuses to return until he reforms his callous ways. Tetreault found a more deal-friendly premise in Step Dawg.” An added bonus is that you can read Tetreault’s old blog before he hit it big.

Writer: Jeff Tetreault

Details: 108 pages (This is an early draft of the script. The situations, characters, and plot may change significantly by the time of the film’s release. This is not a definitive statement about the project, but rather an analysis of this unique draft as it pertains to the craft of screenwriting).

There are those of you who are likely staring at your computer right now saying, “Is this what it’s come to? A script about a man who loses his penis?” To those people I say “you bet your ass.” On the outside, this looks like a juvenile attempt at shoveling shit to the lowest common denominator. And that’s because it is! However, Me and My Penis shovels shit in a thought provoking way. As hard as it is to believe, this is a pretty good script.

The introduction of your hero is so important. You should use that first scene to tell us exactly who he (or she) is. If you put your protag in a boring talky scene or a general “set up the story” scene, we don’t get the information we need about them. This leaves us confused about their identity and the longer we’re confused about who your main character is, the less involving your story is going to be.

Out of all the genres out there, the easiest one to add this scene into is the comedy, so there’s really no excuse not to do it. Rich Johnson is a selfish asshole who fucks as many women as he can. So how do we meet him? We meet him having nasty sex with a woman when the door bursts open revealing his girlfriend and Joey Greco. Yes, Joey Greco from Cheaters. The scene is funny, it’s exciting, but most importantly, it tells us *through action* who our main character is.

Determined to learn from his mistakes, Rich hops into another relationship with Jamie Woo, an Asian hottie, vowing to change his ways and never cheat again. But when he accidentally crashes into a MILF (literally – his car crashes into hers) one thing leads to another and the express train to Blowjobville follows. Jamie, the first girl he’s ever connected with on a deeper level, is horrified and cuts the relationship cord.

In a moment of weakness, Rich laments that he wishes he never had a penis.

Bad. Move.

The next day Rich wakes up without his penis, which is followed by a phone call…FROM HIS PENIS. His penis is in a dark alley and is scared. So Rich heads into town to pick up his penis, only to find out that his penis has taken human form. What. The. Hell?? Not only that, but his penis is even more suave, even better looking, and even cooler than he is!

Forced to allow his penis to move in with him, Rich begins to see firsthand just how much trouble his penis is. His penis starts bringing hookers to the apartment, he starts fucking anything that walks, he’s rude, he’s disrespectful. He’s kinda like Rich times a thousand. I’m not going to tell you that this is deep meaningful multi-layered literature or anything crazy like that, but seeing the physical manifestation of just how much trouble your penis gets you into is nicely played.

Eventually Rich meets Lindsay, a sweet girl who he actually starts to like. Complications arise when intercourse approaches and, of course, Rich can’t do anything about it. In the meantime, for reasons that are a little unclear to me, Rich’s Penis gets really pissed off at Rich and actually wants to kill him. But when he finds out Rich likes Lindsay, he does the next best thing, which is to poach her away. His plan is to have the ultimate sex-a-thon smorgasborg with Lindsay, thereby destroying Rich’s world and, I don’t know, hope he commits suicide afterward or something.

Will Rich get his penis back? Does he want his penis back? Those are the big questions.

So look, here’s the thing. There’s nothing great about this script. I giggled here and there, had a few laughs, and thought the execution was adequate. However that’s not what made this script so memorable. What I noticed right away about Me and My Penis was that it took chances. And that alone puts it ahead of 90% of the comedies out there.

The screenplays that fall by the wayside – the ones that the readers forget as soon as they put them down – are the ones that make obvious choices. Obvious is boring. Now you may think a guy’s penis disappearing then coming back in the form of a human is stupid, but as a reader, I’ve never seen that before. I have no idea where that script is going. So I perk up and start paying attention (assuming it’s capably written of course). It’s like walking into a new city. It’s new, it’s different. You want to explore it.

But what it really tells me is that Tetreault is *trying*. He’s not taking the easy route. He’s challenging himself with an idea that is by no means easy to pull off (you’re basically building a 100 minute story around a 5 minute joke).

And I liked that Tetreault continued to try different things throughout the script. In the scene where he bumps into the MILF, for example, a superimposed flaccid penis appears at the bottom of the screen. As the MILF’s responses to Rich’s questions range from disgusting to hot, the penis erection goes either up or down. Sophomoric? Maybe. Different? Definitely.

One of the big mistakes the script makes though – and one I’m frankly tired of seeing in comedies – is just how little effort is put into the supporting characters. Rich has a friend, Josh, who could have easily been named “Default Best Friend Character,” he was so bland. And you could kind of tell Tetreault didn’t know what to do with him. He wasn’t even funny.

This reminded me, you can’t make someone funny until you understand who they are. If they’re just some cardboard cut-out with no background that you try to force jokes out of, the reader senses that. But if he has some kind of identity, (i.e. “In a Controlling Relationship Guy,” where his girlfriend always tells him what to do) now you have somewhere to go with the character and now the jokes have a base to emerge from. I had no sense of who Josh was, and therefore a lot of the scenes between him and Rich fell flat. So give your secondary characters goals, give them flaws, give them backstory, give them an *identity*. That’s how you build a character up and make them come alive.

Me and My Penis was risky and different and a script that isn’t easy to forget. The execution could use some work and the plot could use some meat but overall, I definitely see why this got so much attention.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: The “superimposed” penis scene got me thinking. It would’ve been so easy to take the obvious route with that scene. The two get into a fender bender, they step out of their cars to deal with it, she seduces him, they go have sex. But the superimposed penis says that Tetreault asked himself, “How can I make this different?” And it’s a question you should be asking yourself whenever you’re writing. Go through all your scenes and ask yourself that question. “How can I make this different?” Not every scene is going to be unique. But if you can add something extra or fresh to a dozen scenes, your script will be way better for it. Never ever settle for obvious. It’s the death knell for screenplays.

It’s Unconventional Week here at Scriptshadow, and here’s a reminder of what that’s about.

Every script, like a figure skating routine, has a degree of difficulty to it. The closer you stay to basic dramatic structure, the lower the degree of difficulty is. So the most basic dramatic story, the easiest degree of difficulty, is the standard: Character wants something badly and he tries to get it. “Taken” is the ideal example. Liam Neeson wants to save his daughter. Or if you want to go classic, Indiana Jones wants to find the Ark of The Covenant. Rocky wants to fight Apollo Creed. Simple, but still powerful.

Each element you add or variable you change increases the degree of difficulty and requires the requisite amount of skill to pull off. If a character does not have a clear cut goal, such as Dustin Hoffman’s character in The Graduate, that increases the degree of difficulty. If there are three protagonists instead of one, such as in L.A. Confidential, that increases the degree of difficulty. If you’re telling a story in reverse such as Memento or jumping backwards and forwards in time such as in Slumdog Millionaire, these things increase the degree of difficulty.

The movies/scripts I’m reviewing this week all have high degrees of difficulty. I’m going to break down how these stories deviate from the basic formula yet still manage to work. Monday, Roger reviewed Kick-Ass. Tuesday, I reviewed Star Wars. Wednesday was The Shawshank Redemption. Yesterday was Forrest Gump. And today is American Beauty.

Genre: Drama – Coming-of-Age

Premise: Lester Burnham experiences a mid-life crisis after he’s fired from his job, which ends up triggering chaos in his suburban neighborhood.

About: Was widely considered one of the best spec screenplays of the last 20 years. But the movie was always going to be a hard sell due to its non-high concept nature. American Beauty went on to become a surprise hit, winning a Best Picture Oscar, as well as 4 other Oscars, including one for Kevin Spacey.

Writer: Alan Ball

Degree of difficulty – 4.5 out of 5

Some of you have suggested that I ditch this mainstream trash and take on movies that are REALLY unconventional. For example, explain why a film like Mulholland Drive works. Well, it’s pretty simple. I *don’t* think Mulholland Drive works. So I’d do a pretty lousy job convincing others of it. I’ve always struggled with Lynch’s appeal. The randomness of his stories always confuses me. So I ask you Lynch-ians, what is the appeal of Lynch’s films? I ask that in all sincerity. I want to know.

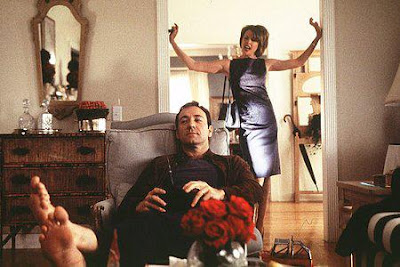

Today I’ll be hitching a ride on Kevin Spacey’s train – whatever that means – and reviewing one of the great movies of the last decade – American Beauty. Recently, I watched this movie with a friend who’d never seen it before. I was like, “How could you not have seen American Beauty? It’s awesome.” And she was like, “I don’t know. I just haven’t.” So I forced her to sit down and watch it, and halfway through she turned to me with this frustrated expression and said, “This is just like Desperate Housewives.”

At first I was angry that she wasn’t appreciating the genius of this movie. But I was also trying to figure out if she knew American Beauty came out a decade before Desperate Housewives, and how this would affect our friendship if she didn’t. But after stepping back and thinking about her comment, I realized just how much American Beauty influenced movies and television. It really inspired a lot of copycats, and for that reason, it can never play as original as it did back in 1999. But it’s still awesome, and it still had no business being as good as it was. You want to talk about degree of difficulty, let’s talk about American Beauty.

American Beauty does something I tell new writers never to do: Follow a bunch of characters instead of following just one. It’s okay to follow other characters when they’re around your character, but to jump back and forth between numerous characters and their individual storylines is basically the same as having multiple protagonists. So instead of having to create only one character compelling enough to carry a movie, you have to create six. In addition to that, multiple characters screw up your act breaks and overall structure. You’re essentially having to create multiple three-act stories within a three-act story, and I’m not even going to get in to how hard that is. So yeah, you’re kinda screwed right off the bat.

Also, like a lot of movies this week, American Beauty doesn’t have a very compelling story. In fact, if I described it to you beforehand, you’d probably get bored within 20 seconds. “Well see it’s about this guy. And he like, gets fired. And then he decides to live his life to the fullest. But see, we also watch his family too. And his daughter wants new breasts. And his wife totally hates him. Oh, and the next door neighbors are this military dad and his pot-smoking son…” It just sounds like a slightly exaggerated version of what goes on in everybody’s neighborhood. Why would anyone want to watch that for two hours?

Finally, Lester is an unsympathetic character. He basically says “fuck off” to anyone who doesn’t want to live by his new rules. On top of that, he tries to fuck his high school daughter’s best friend! Let me repeat that. Our 45 year old protagonist is trying to have sex with a 17 year old High School girl. Conrad Hall, the cinematographer on the film, was so concerned about this that he almost didn’t take the job.

Too many characters: check. Weak story: Check. Despicable protagonist: Check. Why the hell did this work?

Ball was smart. He knew that if he followed a bunch of different characters for an extended period of time without a point, we’d get bored. He needed a connective thread – something to bring all these storylines together. He created it in Lester’s death. Ball tells us in the beginning of the movie that in one year, Lester Burnham will be dead. You don’t think much of it at the time, but later you realize that that one sentence turns the movie into a Whodunnit. It’s by no means the dominant focus of the movie, but it gives the movie purpose. I read a lot of these screenplays where writers don’t use that device and they’re almost always bad. In fact, Mark Forster has one of these movies in development called “Disconnect,” (about how we’re all disconnected because of technology). He doesn’t use this device and as a result, the script wanders all over the place.

Next, Ball adds humor. American Beauty deals with some serious ass subject matter. Stalking, death, murder, physical abuse. But the movie is fucking FUNNY. And we’re only able to feel the pain because we’re allowed to laugh. The 7th line of the movie is “Look at me, jerking off in the shower.” Contrast this with another Mendes movie, Revolutionary Road, which had a lot of similarities to American Beauty, but didn’t have a single joke in it. Despite having two of the biggest stars in the world to sell the movie, it bombed. Coincidence? Not thinking so. American Beauty understands that if you ratchet up the melodrama 100% of the time, the audience will turn on you. Make’em laugh and they’ll go as deep as you dare to take them.

Scandalous. A little scandal goes a long way. Old guy with an underage girl? That’s controversial. Controversy intrigues people. It gets people talking. But what Ball managed to do with this storyline was make you understand why our hero did it. This wasn’t about nailing an underage girl. This was about Lester trying to reconnect with his youth. By getting the young girl, it was the physical manifestation of that goal. Also, Ball did a really smart thing by having Mena Suarvi engage in the pursuit. If she would have been some innocent doe-eyed teenager, Lester would’ve looked like a predator. Because she eggs him on, the relationship doesn’t seem nearly as dirty as it could’ve been.

Finally, what I loved most about American Beauty is that I never knew what was coming next. As a writer, it’s your job to surprise the unsurprisable. The audience has seen everything. The readers have read everything. So safe boring choices aren’t going to cut it. Yet, safe boring choices is what I see 99% of the time. American Beauty has its 40 year old protag befriending his 17 year old pot-selling neighbor who’s dating his daughter. It has his wife fucking her real estate rival. It has 5 minute scenes with bags blowing in the wind. It has military closet homosexuals who collect Nazi dinnerware. I can’t remember a movie that consistently surprised me as much as this one. I just never knew where it was going to go. It shows what can happen when you test yourself as a writer and never go with the obvious choice. That’s something we all need to do more of.

Let me finish with this. I’m of the belief that what you have in the script is what you get in the movie. I don’t believe you can do that much to make a script better than it is. Sure you can do a few flashy things here and there, but in the end, it’s about the emotion, and that comes way before a frame of film is ever shot . However, I will concede this belief in one area: the score. A great score can elevate a movie beyond the script. And American Beauty did that. I don’t think without that score that the movie is as good as it is.

Anyway, great movie. Why do you think it worked?

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[x] genius

What I learned: The power of a framing device. If your screenplay has little to no plot, look to build a framing device around it. For example, Cameron easily could’ve made Titanic about two people falling in love on a boat, but he knew there wasn’t enough story to that. So he framed that love story inside a present-day search for a jewel. Now the entire movie had purpose, as there was a point to telling this love story. The same thing happens here. We aren’t just jumping in and out of people’s lives randomly. We’re trying to figure out who’s going to kill Lester.

The movies/scripts I’m reviewing this week all have high degrees of difficulty. I’m going to break down how these stories deviate from the basic formula yet still manage to work. Monday, Roger reviewed Kick-Ass. Tuesday, I reviewed Star Wars. Wednesday, I reviewed The Shawshank Redemption.Today, like is like a box of chocolates.Genre: Comedy/Coming-of-Age?

Logline: A simple man looks back at his extraordinary life.

About: Forrest Gump is the 23rd most successful film in domestic box office history, grossing 624 million dollars if you adjust for inflation. It stole the Oscar for Best Picture away from The Shawshank Redemption and Pulp Fiction (for those keeping track, the other two movies in the race were Four Weddings and A Funeral and……….Quiz Show???). Gump also won Tom Hanks a best actor Oscar.

Writer: Eric Roth (based on the novel by Winston Groom)

Degree of Difficulty – 5 (out of 5)

Yes! I love talking about Forrest Gump. It’s one of those divisive movies that always gets the opinions flowing. People either love it or hate it. I think it’s a great movie, but I understand where the non-likers are coming from. Let’s face it. It’s a smarmy feel good star vehicle that wants you to love it a little too much. But here’s the difference between Forrest Gump and all the other also-rans jockeying for that blatant heartstring tug-a-thon (like “The Blind Side” for instance). Forrest Gump is DIFFERENT. It’s unlike any movie you’ve ever seen and unlike any movie you’re ever going to see. This isn’t some by-the-numbers bullshit. It’s genuinely original. For that reason alone, it’s worthy of discussion.

Let’s start off with the span of time the movie takes place in. Movies are really good at dealing with contained time periods. Why? Because contained time periods provide immediacy to the story. Characters are forced to face their issues and achieve their goals right away and that makes the story move. This is why a lot of films take place within a few days or a few weeks. Once you start spanning months and years and decades, you lose that inherent momentum, and you’re forced to figure out ways to replace it (which isn’t easy!). Forrest Gump takes place over something like 40 years. Not looking good.

But that isn’t the biggest problem for Gump by a long shot. What truly makes the success of this movie baffling is that its main character is the single most passive mainstream protagonist in the history of film. Forrest Gump doesn’t initiate ANY-thing in this movie. He literally stumbles around from amazing situation to amazing situation like a member of the Jersey Shore cast. All of Forrest Gump’s decisions are orchestrated by someone else. People tell Forrest to jump and he says “how high?”. A main character who doesn’t drive the story? You’ve written yourself into Trouble Town. Next train leads to Screwedville in five minutes.

Another issue is, just like The Shawshank Redemption, Forrest Gump has as much plot as an episode of Dora The Explorer (note: I’ve never actually seen Dora The Explorer but I’m guessing there’s not a lot of plot in it). There’s no overarching goal for the protagonist. There’s no drive. No first act, second act, or third act (although I’ve seen people try to break this into acts – it’s never been convincing). Instead, the film plays out like a series of vignettes – or better yet, a sitcom episode. Tom Hanks is thrown into a crazy situation. Something funny happens. Repeat. It’s a very compartmentalized approach to the story. Why these disconnected misadventures worked was a mystery to me for a long time. But I think I finally figured it out.

Why it works:

It came to me like a flash of light. I hadn’t seen Forrest Gump in forever but there the answer to my question was. Forrest Gump wasn’t a movie. It was a documentary. Documentaries don’t have first act breaks and mid-points and character arcs. They simply follow a person’s life and whatever happens to that person happens. All the documentary has to do is capture it. Now as all documentarians know, documentaries are made or broken by their subject. Without a compelling subject, you don’t have a documentary. And that’s why this film worked. Forrest Gump is one of the most fascinating characters we’ve ever seen. He’s “retarded,” yet doesn’t wallow in it. He does extraordinary things, yet is humble about it. His childlike enthusiasm appeals to the kid in all of us. His situation is ironic (he’s extremely successful yet has the intelligence of a 6th grader). This man has a ton going on underneath the hood.

But the characteristic that most ensures the character’s success is that Forrest Gump is the ultimate UNDERDOG. I cannot make this clear enough. EVERYBODY LOVES AN UNDERDOG. When someone is picked on, looked down upon, is a longshot, we love to root for them. And Forrest Gump is the biggest underdog of them all. He’s physically handicapped (as a child). He’s mentally handicapped (as a child and an adult). Yet he achieves things the rest of us could only dream of. It’s entertaining as hell to watch, and it’s impossible not to feel good for the guy when it happens.

Another key component here is the detail given to the supporting characters, particularly Lieutenant Dan. Remember, some protagonists don’t arc. The story just isn’t conducive to them transforming. That happens here in Gump. But if that’s the case, you should probably have one of your supporting characters fill that role, because the audience wants to see somebody learn something by the end of the film (or become a better person in some capacity). Roth recognized that, which is why he has the eternally cynical character of Lieutenant Dan learn the gift of life over the course of the story.

Speaking of supporting characters, Roth also needed some kind of thread to hold the story together. The plot was so wacky, so disconnected, that had he not added a connective thread, it would’ve come off as a series of comedy skits. He needed a constant. And that’s where Jenny came in.

What’s so cool about the Jenny relationship is that everything goes so well for Forrest…except his relationship with her. I said up above that there’s no goal for Forrest and that’s technically correct (Forrest doesn’t actively pursue anything). But he does keep bumping into Jenny. And he does want her. So because there’s an element of pursuit going on, we become engaged. We want to know, will he get her or not?

Remember, movies are essentially characters trying to overcome obstacles. That’s it. And the greater the obstacle, the more involved we get, the more rewarding it is when our character overcomes said obstacle. What’s a greater obstacle than being in love with someone who will never love you back? It’s the ultimate underdog scenario. And our desire to see if he Forrest can pull off the impossible is what gives this movie purpose. Quite simply, we want to see if Forrest gets the girl. And that’s enough to keep us satisfied for 150 minutes.

I’d be interested to hear why you guys believed this movie worked (or didn’t). When I’m in a bad mood, I hate how cute it can be. But otherwise, I get a kick out of how weird and different it is. It fascinates me every time I watch it.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: If a character has a weakness, don’t allow him to wallow in it. Nobody likes the “woe is me” guy/girl in real life, so why the hell would we like them onscreen? Forrest has a serious disability but he doesn’t let it affect him. He pushes on with a positive attitude. It’s hard not to like someone like that.

In my eternal pursuit to keep you off-balance, I’m breaking out a Theme Week this week. The theme? Movies Roger and I love despite their nontraditional nature. The goal will be to figure out, to our best estimation, why these movies which strayed from conventional storytelling practices still worked. It’s also a very busy week, so expect updates at weird unpredictable times. I wouldn’t be surprised if all 4 of my reviews popped up at 3 a.m. Thursday morning. Roger starts us off with a movie he loved, “Kick-Ass.” Feel free to go back and enjoy my review of the script afterwards. :)

Genre: Action Comedy

Premise: Dave Lizewski is an unnoticed high school student and comic book fan who decides to become a vigilante.

About: Kick-Ass is Matthew Vaughn’s third directing effort (behind Layer Cake and Stardust). What some people don’t know about Vaughn is that before he became a director, he was Guy Ritchie’s producer, producing such films as Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels and Snatch. Kick-Ass stars Nicolas Cage and McLovin, as well as Chloe Moretz and Aaron Johnson.

Writers: Jane Goldman and Matthew Vaughn

Director: Matthew Vaughn

Art is partly to entertain, but partly also to upset. You need those two. That’s vital to keep our society alive. –Yann Martel

This movie so offended Professor Stark, that he leaned over to me at one point and gesticulated, “This is fucking depraved.” I would have laughed at him, but I was too dazed to reply.

Kick-Ass shocked you into Stendhal syndrome, Rog?

I remember the moment in the theater when I started to shake.

My hands were trembling, and if I wasn’t captivated by what was happening on the screen, I would know that my lungs had tightened and that my heart was beating faster. My nervous system was having a definite reaction to the images and noises my brain was trying to process.

Sure, I was on the edge of my seat when Kick Ass and Big Daddy were being tortured on live television by goons who were working for the villain, the local mob boss. As they were being dramatically bludgeoned with every type of weapon imaginable, I asked myself, “Is that the same backdrop they used in one of the torture scenes in Scarface?”

Our heroes were up shit creek, and the tension was milked for all it was worth. These guys were going to die on live television. But at every showing I was, all the audience members knew that Hit Girl was going to arrive anytime now. Sure, Red Mist shot her in the chest and the last time we saw her she had fallen into an alleyway, but we knew that she was trained by her father to take bullets in the chest. My friend leaned over to me and said, “Man, that girl is going to show up and rape all of these guys.”

The power cuts out, the characters watching the online feed can’t see anything. And suddenly night vision goggles flick on. The sound reminded me of that terrifying sequence in Silence of the Lambs when Buffalo Bill is stalking Clarice Starling through the pitch darkness of his house. But then I noticed a HUD.

It reminded me of several videogames, specifically first-person shooters. Doom to Quake to Counter Strike to the USP with tactical knife attachment in Modern Warfare 2.

Yep, Hit Girl was here to save the day, and we watch through the eyes of a child who has been honed into a brutal vigilante by her father as she starts killing everyone in the room.

But then, the goons set her father on fire and a familiar song starts to play. I’m thinking, is this from the Sunshine soundtrack? This sounds a lot like Kanada’s Death Part 2. Holy shit it, is! I’ve listened to this song tons of times while I wrote.

And that’s about the point my geek brain starts to melt and I haven’t seen a firefight so emotional since John Woo’s The Killer. This shit is epic on a Ripley fighting the Queen level.

Well, it didn’t read like that on the page, Rog…

Of course it didn’t.

Those were just blue prints for the sound and the fury as told by filmmakers who knew exactly what they were doing. We didn’t have the performances of the actors, the soundtrack that triggered references to other movies and struck chords in the heart and mind and we didn’t have all the millions of flourishes performed by camera operators and film editors and costume designers and art designers and every single person that added their sweat and blood to the movie.

Kick-Ass is a screenplay that every studio hated. I can only imagine their reactions when they read it. It was probably a litany of, “No no no no no!” “Why is there a twelve year-old girl massacring people in this? You can’t have that! You have to change it!” “This thing changes perspective two-thirds of the way through! You have to change it!” “You can’t have a twelve year old girl say the word CUNT!”

Carson even rated it a [x] Wasn’t For Me.

I was blown away by the movie the first time I saw it. In fact, I saw it two more times the same week. I treated several friends to it, paying for their tickets, because they didn’t think it was going to be a good movie.

It looks so strange. How can it possibly work?

Nicholas Cage gives such an oddball performance, like he became the host body for the ghost of Christopher Walken, who in turn invited along the iconic television spirits of Adam West and William Shatner. And what a bizarre ride it is, with his weird fucking mannerisms that elevate theatrical camp to inscrutable avant-garde. In probably any other movie fantasy circumstance, you would hate this character for what he subjects his daughter Mindy to, running her through a reverse-Clockwork Orange gauntlet, absolutely ruining her life by sharpening her into a tool of vengeance, brainwashed by comic books, videogames and John Woo movies. You would call the guy a douchebag and applaud loudly when he dies.

Except, the guy has a reason for doing it. He’s an honorable cop that was fucked over by Frank D’Amico. His backstory inseminates empathy into the heart of the audience. Prior to his backstory, Big Daddy feels like a mystery, a puzzle piece. But then, his origin story is appropriately told through the device he used to brainwash Mindy, a comic book. And his origin story breaks the sympathy hymen. We start to feel for Damon Macready when we see how D’Amico’s scheme sends him to prison with a disgraced reputation, we start to feel sorry and care for Macready when we see his wife commit suicide as an escape from her despair and loneliness.

By association, we think of these tragic circumstances and Mindy’s birth, and although she’s already a loveable character, we want to see her take up the mantle and turn her family’s bad fortune around. When Big Daddy perishes, his mission not complete, he passes the baton to this little girl he poured all of his dreams into, including his vengeance. And isn’t that what parents are supposed to do? To dream a better life for their children, or to dream so big their goals can only be completed by a generational passing on of the flame?

By the time Mindy is knocking down the castle doors of D’Amico’s uptown stronghold set to the theme of A Few Dollars More, we have to stop and think what we’re really about to see. Are we really about to see a twelve-year old girl, armed to the teeth, walk solo into a secure condo full of mob enforcers? And we already know Mindy is like one of those spy-thriller assassins who has been wiped clean and programmed via secret government experiments, except she’s the freakish, geeky and bizarro Marvel Max Universe version of that. And we can’t forget, she’s a fucking twelve year old girl! Isn’t at least some part of your brain curious about what that sequence looks like? And if you’ve made it this far into the movie, isn’t your heart invested in the fact whether she’s going to be able to complete her father’s mission? I’m not even talking about the possibility of her dying. She’s willing to make that sacrifice. But is your heart involved in her journey of vengeance? If the answer is no, then maybe you don’t like revenge stories.

And what about Dave Lizewski?

Look, I have friends that are staunch superhero fans and refuse to see the movie. One has a compelling reason. She’s a huge Avengers fangirl. I remember talking to her and she said, “I just can’t do it. It’s not what I read superhero comics for.” And you know, I can understand that. Some people like their superhero stories and themes preserved in the purity that comes with the nostalgic and kid-friendly Marvel Universe.

They think Kick-Ass satirizes the world of superhero comics and its fans sans the courage, sans the heroics, sans the message that an ordinary person can rise up out of everyday circumstances and do something extraordinary. They think it’s just being ugly, potty-mouthed, catering to immature fanboys, and making fun. Well, if they sat down to watch it, they would see that the movie would not work if it didn’t have this courage, this heroism, this, “I’m an ordinary person but I am truly capable of super-heroic things.”

It’s a satirical, perhaps lunatic brew that possesses the same heart of the superhero tales that makes them mythic, iconic. The same blood pumps through Kick-Ass that makes our modern superhero mythology sacred.

Dave has a genuine sense of justice that seems hardwired into him, just like it may be hardwired into all of us. A moral, instinctual sense of right and wrong. How do we know? He doesn’t like being mugged. He doesn’t like seeing his friends being mugged. We see how upset he gets, that Travis Bickle inner-outrage bubbling underneath his skin when he witnesses lowlifes steal, cheat and murder.

It’s moving when he defends a man against a trio of thugs and says his name for the first time. Isn’t that weird? In any other circumstance, it would probably be cheesy. But here, it works. Out of breath, brutalized, but still fighting, he says with conviction through a bloody mouth, “I’m Kick-Ass.”

Why does it work?

Because it’s a nerdy kid with a sense of justice, who is tired of watching people be mistreated, who puts his life and the line and takes a stand for something he believes in. It’s an act of courage, of heroism, and that speaks to our hearts. And no matter how campy it can be, there’s something that still resonates with us.

The structure of the screenplay feels weird. It’s handicapped by the superhero origin structure, but the third act feels like it’s more about Hit Girl than Kick-Ass. If I wrote a spec that changed perspective and focus two-thirds of the way through, I’d be crucified on the spec market.

Maybe. But it doesn’t really matter. Vaughn and Goldman are making a movie, they’re not trying to sell a screenplay to a production company or studio.

And plus, it works.

The focus is flipping over to a character we haven’t quite seen before. Perhaps Hit Girl’s closest filmic prototype is Mathilda of Luc Besson’s Leon, but only after she’s been strained through a filter of Wuxia tales and first-person shooters. She has a strong heritage of badass female characters, everyone from Ripley of the Alien films to the femme fatales in Kill Bill, but the difference is we’ve never seen someone so young, someone that only a pedophile would view as an object of desire.

She’s unique.

As such, we are itching to watch this diminutive killer unleash hell on all of her enemies. Even if takes her half an hour of screen time, we are willing to watch her do this. If we were switching to a lesser character, this perspective and focus shift would be a miscalculation, indeed. The movie would collapse on itself and would become victim to our ever diminishing attention spans.

Carson writes about the difficulties in crafting an origin story in the traditional three act structure. He posits that in most screenplays, the first act is about setting up the main problem the protagonist has to contend with. But with the superhero origin story, this main problem gets postponed until later in the story because the first act is all about introducing the character and how he becomes a hero.

Well, what’s wrong with that?

Most of origin stories do both at the same time. While we’re introduced to Dave and his metamorphosis into Kick-Ass, we’re also introduced to Frank D’Amico, the mob boss, and the problem he’s having with some very good vigilantes. Isn’t that the introduction of the main problem? Everything is set up, and I can look at the structure of the movie and break down the three acts into three ideas: The first act shows us the dangers of being a vigilante in the real world; the second act is about smart, deadly vigilantes who are capable of heroics, and the third act becomes a paean to full-blown, mind-blowing superheroics we read about in comic books.

And although the third act focuses largely on Hit Girl, Dave must make a decision to accept responsibility and become a true hero. His actions have plowed through the city, exposing vigilantes who were effective in crippling a local mafia, and as a result his call-to-arms has gotten people killed, including Big Daddy. His courageous actions have tragic consequences, and instead of throwing in the cape, he chooses to accept these consequences by continuing to stand up for what he believes in, and in the process redeems himself by aiding Hit Girl in the completion of her mission (Dave is the audience’s avatar for this crazy world).

There’s a universal lesson there.

Sometimes, when we do the right thing, there’s collateral damage. When that happens, we can let fear take over, we can stop. We stop believing in ourselves. We begin to doubt. We let our dreams and goals die on the vine because we’re afraid of the consequences. The thing is, that’s usually the moment we have to keep pushing forward.

And that’s what Dave does.

Even in the face of doubting his own abilities, he continues to do the right thing.

The resolution is bloody, exciting, offensive, entertaining and satisfying. Hit Girl blazes and slices and dices her way through rooms and corridors full of bad guys. Dave gets to save her from a bazooka attack with jet-pack Gatling guns. Hit Girl goes head-to-head against the man who is responsible for the deaths of her mother and father, and Kick-Ass goes up against Red Mist. For a hymn to comic books, superheroes, John Woo movies, Sergio Leone and revenge sagas, the movie delivers on all fronts, emotionally and kinetically.

It’s a successful mash-up for fans of superhero origin comics and the cinema of violence.

[x] impressive

What I learned: When Carson told me we would be doing another Theme Week, he presented me with a list of movies he chose that tell their stories in a slightly untraditional manner. Part of me thought, well, what’s traditional? The other part of me knew what he meant. As a guy who studies modern spec screenplays, you could say I pay attention to mechanics, to formula, to pattern. If I read a screenplay and I feel that something isn’t working, I’ll dig in and try and find out why: nine times out of ten it’s because someone doesn’t have their storytelling basics down. Or they miscalculated and made a decision that hurts the story.

But it goes both ways.

In the screenplay world, there are oftentimes when the story isn’t allowed to just be the story. People will come in with different opinions, and they want to change it, make it adhere to Joseph Campbell or some narrative pattern that can feel by-the-numbers and cookie cutter.

And you know what?

You should listen to these people. Sometimes they’re right.

But sometimes, they’re wrong.

I wonder if a great screenplay guarantees a good movie. I remember reading Law Abiding Citizen and thinking, man, this is fucking awesome! Then I remember watching the movie and thinking, man, what happened!

I don’t think there’s a form of storytelling that is subject to more scrutiny than a screenplay. But it makes sense. They’re blueprints. You don’t drop millions of dollars into a building without studying the blueprints to make sure it’s sound and free of error.

But that’s something we ought to remember.

Screenplays are just blueprints for light and sound.

And sometimes, the sound and the fury jumps off the page like a miracle, defying people and narrative weaknesses they calculated as odds, and the celluloid burns like a star that induces Stendhal syndrome if you stare at it directly.

Genre: Drama/Supernatural

Premise: A young man with a promising future is responsible for the death of his brother. When he realizes he can still see and talk to his brother at the cemetery where he’s buried, he abandons his former life and becomes a manager at the cemetery.

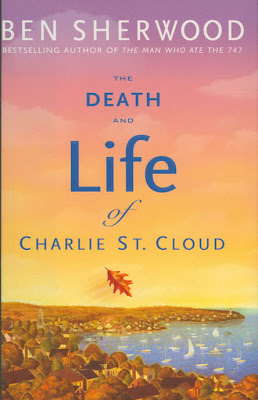

About: Starring Zac Efron, Ray Liotta and Kim Bassinger, this script was adapted from the Ben Sherwood novel. You may recognize Sherwood as the author of the book “The Man Who Ate The 747” which Stark reviewed just a few weeks ago. St. Cloud is the project Efron painstakingly chose over reinventing the Footloose brand. One of the writers, Craig Pearce, wrote both Romeo & Juliet (Baz Luhrmann) and Moulin Rouge. The other, Colick, wrote both Beyond The Sea and October Sky. Charlie St. Cloud hits theaters on July 20th.

Writers: Craig Pearce and Lewis Colick, based on the novel by Ben Sherwood

Details: 114 pages – Undated (This is an early draft of the script. The situations, characters, and plot may change significantly by the time of the film’s release. This is not a definitive statement about the project, but rather an analysis of this unique draft as it pertains to the craft of screenwriting).

So Zac Efron wants to be taken seriously. Gone are the dance moves and the high school cliques. Say hello to the new Efron. Period pieces like “Me and Orson Wells.” Thrillers where he plays a CIA spy. He’s even going to portray a coke runner in the drug-fueled Snabba Cash remake. I just feel sorry for those poor teeny boppers. Their pin-up has leapt off the wall. While 17 Again and Me and Orson Welles were appetizers, the first major entree in the “Take Zac Efron seriously” meal is “Charlie St. Cloud,” a drama where Efron actually gets to play a 30 year old (though I can’t imagine they haven’t made him younger since he signed on). It’s heavy on the drama and requires a wider range than anything Efron’s done before. So is the script he signed up for any good?

It’s 1995. Charlie (athletic, tall, good looking, senior class president, basketball star, sailing star) is one of those lucky bastards who won the genetic lottery. He’s got it all. And not only does he have it all, he lives in a town that beats it all – a small postcard of real estate right off the ocean. You know what people do here in their spare time? Sail. Talk about the life. Where I grew up you spent your spare time experimenting with heater forts in order to stay warm through the day.

Charlie’s best friend is his 12 year old brother, Sam. You couldn’t split these two apart with the jaws of life. And that may have been my first problem with the screenplay. In what universe are brothers best of friends, much less brothers who are 18 and 12. Not that big of a deal but my “huh? meter” did start beeping. Anyway, these two like to go sailing together, play catch together, watch the Red Sox together. They’re the best of buds.

But one night while driving home, Charlie smashes his car into something not soft and Sam dies. Wow, that sucks. However, Charlie’s shocked to find out that he can actually SEE Sam at the funeral. He quickly realizes that he has some power to see dead people, and in order to be around his kid brother, Charlie ditches all his previous life plans and takes the managerial job at the cemetery. Twelve years go by before we catch up with Charlie again.

All grown up (and 30 years old), the highlight of Charlie’s day is still seeing his bro. Now there are some rules to seeing Sam. He can’t wave his magic wand a la Harry Potter and say “Samus Appearus!” He can only spend time with Sam at sunset. Before and after the sun sets, no Sammy. Don’t ask me what happens when it’s overcast.

Now as you can probably guess, people in town think Charlie’s a little…….weird. He doesn’t talk to anyone, he doesn’t do anything. It’s all cemetery all the time. And since he can’t tell anyone why, Charlie has to pretty much sacrifice real life for an imaginary one. (On a completely unrelated note I’ve always wanted to write a movie called “Cemescary.” I just haven’t come up with a story yet).

Into the mix pops Tess, a 24 year old beauty who, like that really bad 16 year old Swiss sailor chick who likes to use government money to save her ass whenever she inevitably screws up, Tess too wants to sail solo around the world. In fact, Tess is a little bit of a celebrity, and she happens to be using Charlie’s town as her launching point.

So one day Tess secretly heads off to practice before her big trip and gets stuck in a huge storm. The last thing we see is a huge wave and a cut to black. The next day, Charlie notices Tess at his cemetery. Hmm, I wonder where this is going. So Tess and Charlie start hanging out and falling in love and stuff. This of course starts to infringe upon brother time, and that’s a huge problem, because if Charlie ever misses a day with Sam, Sam will disappear forever.

(MAJOR SPOILERS BELOW)

Now this is based off a book, so I’m not really spoiling anything, but eventually Charlie and Tess realize that she’s dead, which puts a major crick into their relationship because you can’t marry a dead person. I think there’ a law against it somewhere. However, in a late double twist, Charlie realizes that Tess actually ISN’T dead. She’s barely alive somewhere out on her boat and she won’t live unless someone goes out and saves her. Charlie, with his added ESP powers, is the only person who can do this. Of course, if he goes after Tess, he’ll miss his daily meeting with Sam, and that means Sam will be gone forever. What ever will Charlie choose to do?

Man, I have some mixed feelings about this one. It starts off terrrrrible. I mean roll your eyes every 20 seconds cheese-factor times 8 billion terrible. For example, to show how close the two brothers are, they go to a Red Sox game, and the Red Sox hit a game winning home run, which is heading right towards Charlie and Sam. And Charlie holds Sam up to CATCH THE GAME WINNING HOME RUN. I’m not kidding. It doesn’t stop there though. Later, after Sam dies, we get Charlie falling to the ground accompanied by the ubiquitous anguished cry into the sky, “WHY DID YOU LEAVE ME!?” I’m hoping some smart editor burned that film. But yeah, there’s enough cheese here to feed half of Wisconsin.

The Charlie and Tess stuff is okay, I guess, but introducing a girl who wants to sail across the world felt like a completely different movie. I suppose inside a 400 page book where you have time to segue and explore different things, it may have flowed naturally. But in the tight constraints of a screenplay, it was like, ‘I thought we were telling a story about a guy who sees his dead brother. Now it’s about a girl who sails across the world?’ It felt clumsy.

But the biggest problem with the script was that outside of the Tess sailing thing, any seasoned moviegoer was 40 pages ahead of the story the whole time. We knew the brother was dying. We knew the girl was dead. We knew exactly how the relationship would unravel. It was hard to enjoy because there just weren’t any surprises.

However, I will admit, things did change in the final 40 pages. I thought for sure they were going to find out Tess was dead, which meant they wouldn’t be able to be together, but then, probably, in a final twist, Charlie would either kill himself or find out he was dead too. Instead, we find out Tess is still alive and from that moment on, you’re genuinely wondering what’s going to happen.

This was highlighted by incorporating “The Choice,” – the moment near the finale where your main character makes a choice between staying the same or changing. For Charlie, that means holding onto the past or moving into the future. If you do a good job setting this up, it can be the most emotionally satisfying moment in the script and the cornerstone of the climax. In a movie like “L.A. Confidential,” for example, Ed Exley (Guy Pearce’s character), has a choice at the end to either continue to “follow the rules” or become “dirty.” He chooses to be “dirty” and shoots the captain in the back. The choice cuts to the very core of what he’s been battling with the whole time, so it resonates. I’m not saying Charlie St. Cloud is on that same level, but I thought the choice itself was well-constructed.

Unfortunately, the first act was way too cheesy and melodramatic, and the love story was only so-so. This shouldn’t bother Zac Efron’s younger female audience base as much, but it did bother me.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: If you’re building up to a shocking tragedy in your first act, try not to overdo the “everything’s perfect” scenario that precedes it. I mean the love between the brothers here is so over the top that we knew without question Sam was a goner. Audiences are so savvy these days. They know something’s off when a character in a movie has it too good because movies aren’t about people who have it good. Movies are about people who run into problems. So if you want that tragedy to truly shock us, be a little more subtle with the character’s good fortune.