Genre: Family Film

Premise: A young man in the Lego universe learns that an evil villain plans to glue all of Legoland together, thus stripping future Lego generations of the ability to create stuff.

About: These writers worked in TV for a good 8 years before getting their first big feature break, which was Cloudy with a Chance of Meatballs. That TV work consisted of shows like How I Met Your Mother and Clone High. They also directed 21 and 22 Jump Street. And are directing this movie! Slash Film asked the Lego writers a good question. How much of this was you guys writing a story and how much was it Lego pushing a product and wanting to sell toys? Chris Miller gives a great answer: “Well, we were very clear up front that the only way this movie was gonna succeed was if it didn’t come from the top down. It didn’t feel like it was a corporate commercial. It didn’t feel like Lego was saying, “We wanna sell these toys, tell a story around them.” It had to feel like it was coming from outside the company. It was filmmaker and story driven and that it was using Lego as a medium. Now obviously, you know, they’re gonna wanna sell toys based on the movie. And we said, obviously if we’re making something that doesn’t have cool vehicles in it and interesting characters, then we’re not doing our job anyway. We’re not gonna make a Lego movie that isn’t about cool Lego stuff. And we went to Denmark to visit and see the type of things that they make there and it definitely inspired us from what Lego’s core values are about and the type of things. But we were thankfully not in a situation where they were dictating anything to us as far as what we were doing. And sort of reacted to the things we made and thought “Oh yeah, we can sell toys based on this, this and this.” You can read more of the interview over on Slash Film.

Writers: Chris Miller & Phil Lord

Details: 110 pages (2010 draft)

I feel left out of the joke. Everyone I run into is like, “Oh my God! Oh my God! Lego movie!” I see these reviews on Rotten Tomatoes, which are like, “Lego Movie makes Toy Story look like Movie 43!” By and large, everyone thinks this flick is going to be awesome. Don’t get me wrong. Legos are cool. But are people really THAT into this??

When I watch the trailer, it looks like one of those “everything and the kitchen sink” trailers. I guess that makes sense because it’s the Lego universe and the Lego universe encompasses… well, all of pop culture (I’m sure there’s a Kim Kardashian lego figure available somewhere – probably in Japan), but it looks like sensory overload to me.

Still, I got to thinking and realized we don’t cover the family film genre here on Scriptshadow much, and because it’s such a huge piece of the Hollywood meal plan (read – studios pay lots of money for people to write these things), it wouldn’t be a bad idea to dissect how they’re written. Not only that, but after reading the Lego script, I learned something HUGE about how to pitch assignments. So you’re definitely going to want to stick around for that!

Emmet lives in Legoland. This is a very structured city where everything is the same. People follow rules. They do things by the book. And most importantly, they’re NEVER CREATIVE!

Unfortunately, the 22 year-old Emmet (who lives with his mom), doesn’t operate that way. Emmet is different. He’s creative. He LIKES to step out of the norm and do silly things every once in awhile. At the same time, he’s ashamed of it. Emmet wishes he could live the easy life and be like everyone else. He wants to be your normal average predictable person.

As Emmet tries to come to terms with all this, his mother is kidnapped by the evil overseer of Legoland, Black Falcon! And his ex-girlfriend, Lucy, who now happens to be a superhero, drops in and tells him that they have to get her back. You see, Emmet’s mom is the chosen one, the one who’s going to save Legoland from becoming boring and stagnant forever!

This requires recruiting a bunch of the masterbuilders and taking Black Falcon down. So Emmet and Lucy get a pirate named Neckbeard (who’s just a lego head – and Lucy’s current boyfriend), Batman (of course), a space lego man named “Benny the Spaceman,” and a half-retarded lego-creature named Duplo.

What they find out is that Black Falcon is planning on using the “Kragle” (which turns out to be short for “Krazy Glue”) to permanently GLUE all of Legoland together forever! So that no one can ever take legos apart and put them back together creatively! Everything will always be boring and the same. Noooooo!!! Measly Emmet will have to find the strength within to defeat this mad Lego… creature. And save Lego-mania forever!

So, is it true? Do we have the next Toy Story on our hands? Well, granted this is not the final draft (I saw Wonder Woman in the trailer, and she isn’t in the script), but it’s safe to say, no it is not.

Whereas Toy Story is a meticulously crafted screenplay that marries character, story and theme seamlessly in every minute of its running time, The Lego Movie feels more like one giant ride of cute. Actually, it’s almost identical to Cloudy With A Chance Of Meatballs in that sense. It’s not amazing. But it’s just really really cute.

Halfway through the read, Miss SS turned to me and said, “Isn’t… that movie supposed to be funny?” “Huh?” I asked. “Isn’t the Lego movie supposed to be funny? I haven’t seen you laugh.” And that made me laugh. And then I realized that the first time I had laughed since I started the screenplay was in reference to something outside the screenplay. And that wasn’t good.

I think with these really big family tentpole scripts, you’re basically trying to write the best Screenplay 101 script you can. It’s a family film, so it’s not about taking chances. The key demo isn’t going to be upset if your midpoint shift isn’t that original. The studios want Blake Snyder beat sheets for these films, and your job is to be as inventive as you can within that “beat sheet” framework.

And I think Chris and Phil do a good job. This is straight down the middle, 3-Act, unabashed Hero’s Journey stuff from start to finish. You have Emmet, who’s “different” because he likes to be creative. He doesn’t fit in (quick note: main characters who “don’t fit in” are used effectively in 7 out of 10 animated/family movies). His world is thrown into disarray when his mother is kidnapped. Emmet must join forces with an old girlfriend (unresolved relationship that leads to lots of conflict during journey!), face tons of obstacles, and, in the end, find the strength/belief within himself to defeat the evil villain.

We have clear goals/stakes/urgency (stop the villain/world will be super-glued together if you don’t/only hours left before the villain enacts his plan). It’s all laid out how you’d expect it to be. Which was why I was never all in. I think you guys believe that I’m about following rules all the time. Not true. You follow rules MOST of the time, then break them strategically in certain spots, in ways that will separate your script from everything else out there. If you follow EVERY rule, your script is going to be predictable and (probably) boring.

As far as how to write these specific TYPES of films, you’re always looking for your hook, then exploiting that hook as much as possible. Here, the hook is the legos, obviously. What makes legos different? Creativity, right? That you can turn them into anything your imagination can think up. So there are a lot of fun little moments where lego vehicles crash. All the legos get scattered, and the characters quickly rebuild the pieces into, say, a helicopter, then fly away. There was a lot of that.

But the creativity kind of stopped there. Seeing things leap in the air, then be turned into something else – that’s cool the first couple of times. Then it becomes “been there done that.” Then there was the story, which, while well-executed, never got past the amusing stage (at least for me). It was fun. But never rip-roaring funny. It was exciting, but never “Holy shit! I’ve never seen that before!” And I think if you have a lego movie, you should see some things you’ve never seen before. Who knows, maybe they’ll have added this in the final cut. It just wasn’t here in this draft.

Amusing. But could’ve been better!

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: I learned a big one today. Now I have no idea IF this is how the writers got the job, but remember, when you’re a writer, you’re basically rushing around town, trying to win the big assignments, the movies that are going to pay out 7 figures, movies like Legos. And I think I know how today’s writer-directors’ pitch won them the job. If you really want to impress producers, find out what their property is REALLY ABOUT, then pitch a STRONG THEME that explores that aspect. So think about it. What are legos really about? They’re about “creating,” right? They’re about building something completely crazy out of your own imagination. So our writers pitched a movie of a lego world that didn’t allow creativity, that didn’t allow the very thing that legos represent! Our main character, then, was secretly the only creative person in the city. He was an outcast. And he must go on a journey to free the people from this structured boring life. This pitch had a theme that explored the core of what legos represent! So the next time you get coveted to pitch one of the big assignments, find out what the property is about, and pitch a story with a strong theme that explores it!

Genre: Drama

Premise: A young drummer at a prestigious music school is challenged by the department’s ruthless headmaster to be the best he can possibly be, no matter what the consequences.

About: Writer-director Damien Chazelle is quickly making a name for himself as an up-and-coming talent in Hollywood. He recently wrote the Elijah Wood starrer, Grand Piano (whose script I reviewed here) and now he’s written AND directed his first “major” film, with Whiplash. Whiplash was the darling at the Sundance Film Festival, winning both the audience award and the dramatic award. It stars Miles Teller, an up-and-coming talent of his own, who just starred in this past weekend’s “That Awkward Moment” as well as last year’s The Spectacular Now. Chazelle graduated from Harvard and got his start by writing and directing a small musical called “Guy and Madeline on a Park Bench.” He also was hired to pen The Last Exorcism 2 (which is kind of an oxymoron, right?). Me guesses that put enough money in Chazelle’s pocket to write the films he wanted.

Writer: Damien Chazelle

Details: 111 pages (March 2012 draft)

I’ve been skeptical of this one from the beginning. A movie about… drumming? About drummers competing?? Okay okay, yeah I know. You can write a good script about anything. In the end it’s about the characters anyway, so what should the subject matter matter? But a movie about… drumming??

On top of that, it’s starring Miles Teller, Hollywood’s new can’t miss star. No, I don’t dislike Miles. I think he’s really talented. The Spectacular Now was in my Top 10 of last year, and a big part of that was because of him. But the thing is, once Hollywood picks someone to be their It Boy (or It Girl) the critic and independent community become a little blinded by that star’s shine. They start anointing every film he’s in as amazing because the shine has blinded them from seeing the film’s faults. I’ve seen it happen many a time before. Shia LaBeouf’s career comes to mind (Eagle Eye and Distubia? Come on, they were O-KAY. But I wouldn’t call them “good”).

With that said, it’s not easy to snag BOTH the dramatic and audience awards at Sundance. The dramatic award usually goes to some really artsy esoteric film about a Romanian man who makes candles. The audience award goes to the feel good movie of the festival. Well, this one apparently made everyone feel good, judges and audiences alike. Let’s see if the screenplay made me feel the same.

Whiplash’s plot is kinda simplistic. Actually that’s an understatement. Andrew Neyman, 19 years old, a sort-of outcast, goes to a special music school in New York. He plays the drums, and he’s good at them. Not great, but good.

So one day, while playing, this guy named Fletcher, who’s the Da Vinci of this school’s orchestra and one of the scariest men alive, comes in to a practice session to listen to Andrew play. He’s not overly impressed, but there’s something in Andrew’s eyes that tells Fletcher to give him a shot.

So Fletcher makes him an alternate on the school’s band, a band many consider to be the best in the country. After a screw-up by one of the other drum chairs, Andrew’s able to grab one of the main spots, and he does good enough to make him a full-time member.

Which seems like a good thing. The problem is, Fletcher is a fucking psychopath and obsessed with pushing his players beyond any and all reasonable thresholds. He curses at them, throws things at them, calls them derogatory names like “faggot” (GLAAD is going to have a field day with this one). He does it under the guise of pushing his students to be great, but the truth is, he’s just a deranged lunatic.

So he pushes Andrew and pushes Andrew and pushes Andrew until finally Andrew cracks and beats the shit out of him. This leads to him getting kicked out of school, and Andrew giving up on his dream of drumming. He’s eventually approached by a law firm who’s been trying to take down Fletcher for awhile (this is around page 80). They want him to anonymously testify against Fletcher to get him kicked out of the school.

Andrew does, then starts a new life as a paralegal. That is until he runs into the now-fired Fletcher, who wants Andrew to play in a new band of his. Andrew decides that he still loves drumming and so agrees, only to find out when he gets to the final big concert that he’s been set up to fail, to be humiliated by Fletcher.

I’ve never read anything like Whiplash. It’s a really strange script. Truthfully, it’s probably not meant to be enjoyed in screenplay form. This movie is all about the music, and music doesn’t translate well on the page. So you have to take that into consideration when judging it.

But it took me awhile (almost 80 pages) to figure out what this script was REALLY about. It wasn’t about a story (which is what I kept waiting for). It was about two characters battling. And when I say that, I MEAN it. There is virtually nothing else going on in this script. No love interest. No backstory. No character dimension. Just a battle.

And that’s the strange thing about Whiplash. The characters are drawn one-dimensionally almost as a way to accentuate that battle. Andrew is “I want be great drummer.” Fletcher is “I am evil teacher.” There is no other shade to them. What’s surprising is that even with these pancake-flat characters, Chazelle almost makes it work. Because the battle between them is SO. DAMN. INTENSE.

But man, I could only take 5 scenes of Andrew violently banging on the drums as Fletcher yelled at him before I was like, “Okay, I get it!”

There was something about it all that rubbed me the wrong way and I’m trying to figure out what that was. Part of it was that Fletcher was SOOOOOO over the top in his insanity (faggots and calling Andrew’s dad a failure and throwing things at Andrew) that I was always aware (during those times) that the character was being written.

And I didn’t like Andrew’s take on life either. His philosophy is basically “I don’t have friends and family and I don’t care. I just want to be great at drumming and have a bunch of people look up to me and then die.” Talk about a depressing way to live your life. And that’s our hero!

So there was a little bit of Real Housewives of Pick Your City going on here, where you don’t really like anyone you’re watching. But all the crazy conflict keeps you from turning the channel.

Are there some lessons to learn from the script? Well, Chazelle does well by bringing a time-tested always-works movie device into play: the unorthodox teacher. From Dead Poet’s Society to The Karate Kid to The King’s Speech, these types of characters typically delight readers and audiences. And he does do something different with the character by making him really really really mean.

And Chazelle mined a thoughtful theme here. Friends and Family vs. Greatness. One of the ways writers like to explore their themes is by posing it in a question, then using the script to debate that question. And I felt that here. The theme question was probably something like, “Is it better to be great at something and friendless or be average and surrounded by friends?”

A few screenplay teachers will say that you want at least one scene in your script that directly addresses that question, and we get that here. Andrew gets in a fight with his uncle at a family dinner, arguing just that: that he’d rather die friendless and be great at something than be like him (his uncle) who’s surrounded by love but is a nobody.

And actually, I think that’s why this script ultimately left a bad taste in my mouth. Not because it was badly written. Cause it wasn’t. (spoiler) But because in the end, Andrew chooses to be great, to live a friendless lonely existence at that expense. And that just made me really really sad. In a script that basically shuffled back and forth between lots of drumming to lots of practicing to lots of music terminology to lots of yelling, to go off on that note felt lonely and sad. And it’s hard for me to endorse something that makes me feel that way.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Love the subject matter you’re writing about. – This is Chezelle’s third music-inspired screenplay and you can tell he loves the subject matter. He knows EVERYTHING about it and he CARES about everything to do with it and that comes out on the page. Find a subject matter you’re an expert in and you love, then bleed it onto the page. I can’t guarantee your story will be great. But I CAN guarantee that your script will have passion. And your script NEEDS passion to be successful.

note: Whiplash review coming tomorrow.

Genre: Thriller

Premise: A Los Angeles drifter with big dreams finds himself drawn into the world of “nightcrawling,” a practice where independent videographers search out violent crimes and sell them to news shows.

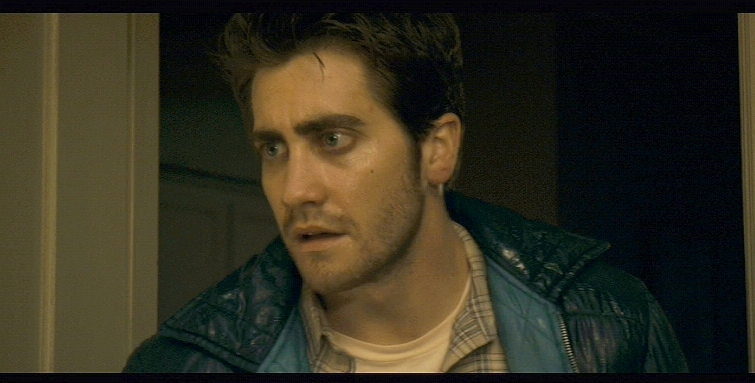

About: Recently Jake Gyllenhaal left the giant Disney musical, Into The Woods, because funding for this film finally became available and he loved the script so much, he didn’t want to pass it up. I figure if someone’s passing up big studio money to do a small indie film, the script must be pretty great. Dan Gilroy is best known for writing The Bourne Legacy, The Fall, and Two For The Money.

Writer: Dan Gilroy

Details: 108 pages – 11/27/12 draft

Jake Gyllenhaal has been trying to break through into that A-list category for awhile now. But no matter what he does, he’s still stuck in that B – B+ category. Actors who can bring you 10-15 million on opening weekend, but not much more unless they’re paired up with a big actor. So how do you get onto that A-list? It’s simple. Find a great character. If you can find a great character and you nail the performance, the film stays in the theater longer, which leads to more accolades, which leads to more publicity, which leads to possible Oscar nominations. And all of a sudden, when that big new production needs a star, the first name on producers’ lips is… Jake Gyllenhaal!

Which is exactly why you want to write interesting unique characters. Every actor out there is dying to find that character that’s going to light up their career. Today’s script is a perfect example. Gyllenhaal actually left a film where they drape you in money just because of the Nightcrawler lead. That’s how rare these opportunities are and why actors jump when they get their chance because writers just don’t write enough juicy characters. And make no mistake, the role in Nightcrawler is about as juicy as they get.

20-something Louis “Lou” Bloom is like a lot of people in Los Angeles. He’s trying to become relevant. He’s trying to get a job. He’s trying to make money. He’s trying to find a place that doesn’t look like a janitor’s closet. The man is desperate to find a life of importance.

Lou is also… strange. You aren’t going to find an easy way to describe him but if pressed I’d say he’s an ambitious sleazy sociopathic hustler with a tinge of autism. He will steal your bike the second you turn away, then sell it to the bike store on the next corner with a load of bullshit so tall it’d dwarf the tallest hill in Hollywood.

Here’s a little taste of that action, where he’s trying to run up the price on the bike store owner who sees right through him: “This is a custom racing bicycle, ma’am, designed for competitive road cycling. This bike has a lightweight, space-age carbon frame and handlebars positioned to put the rider in a more aerodynamic posture. It also has micro-shifters and 37 gears and weighs under six pounds. I won the Tour de Mexico on this bike.” Bike Store Owner: “No bike has 37 gears.”

So one day, Lou happens upon a nasty car wreck where a young woman is stuck inside a burning vehicle. He notices a couple of independent videographers taping the ordeal. Armed with every cop radio frequency in town, it’s clear these guys race around to wherever bad shit is happening, tape it, then sell the footage to the news stations.

Fascinated, Lou buys himself his own video camera and starts doing the same. The big difference between Lou and his much more experienced competition is that Lou is, well, FUCKING CRAZY. He will drive 95 on side streets to make sure he gets to wherever the hell the action is first. This means he always gets the best footage, and he starts selling it to the news shows for big money, or one station in particular – K.S.M.L.

K.S.M.L. is in the gutter and therefore desperate. That means they’re willing to show crazier violence and pay more. Lou takes a particular interest in the director of K.S.M.L.’s news, Nina Romina. She’s twice his age but that’s just fine. Lou has a thing for older women. When she doesn’t show interest in him, Lou just uses his leverage: “You don’t want me [sexually], I don’t wanna give you the footage I found.” Nina knows Lou is her meal ticket and therefore, obliges Lou’s advances.

Eventually, however, the oven starts burning too hot. Sweeps is coming up and while Lou is still the best in the business, Romina needs something huge. It’s at this point that Lou realizes, if he’s going to find a story truly mind-blowing story, he can’t wait for the news to happen. He’s going to have to create it himself.

Man oh man oh man is Gilroy a good writer. This script just flew by. He’s one of the few writers who can be descriptive with barely any description at all.

LOS ANGELES

Shimmering in night heat… THRUM of civilization… a FREEWAY feeds into the city as a SEMI blasts by and CUT TO

A COYOTE

Loping across a RESIDENTIAL STREET in the hills… it stops under a street lamp… darting away and CUT TO

THE L.A. RIVER

For those of you who’ve read my book, you know one of the movies I broke down was Taxi Driver. But I almost didn’t include it. I thought to myself, people don’t write like this anymore. You can’t write Taxi Driver in this day and age, so what’s the point of using it as an example? I now realize I was wrong. You can write a movie like this. You just have to update it to a new time, to a new collective sensibility. You can still have a dark fucked up character running around a city doing dark questionable things, but it needs to be faster. It needs to have more pop. More energy! Enter “Nightcrawler.”

And, of course, if you’re going to write the next Taxi Driver, you gotta have your modern day Travis Bickle. Dan Gilroy found that character in Lou. This guy is just… I can’t even summarize him really. He’s that complex. There’s this moment that encapsulates him best where he basically blackmails Nina into giving him more of the action. However, there’s a detachedness to the way that he speaks, as if he both wants and doesn’t want what he’s asking for:

“Now I like you, Nina, I look forward to our time together, but you have to understand that 25,000 isn’t all that I want. From here on, starting now, I want my work to be credited by the anchors and on a burn. The name of my company is Video News Productions, a professional news gathering service. That’s how it should read and that’s how it should be said. I also want to go to the next rung and meet your team and the anchors and the director and the station manager, to begin developing my own personal relationships. I’d like to start meeting them this morning. You’ll take me around and you’ll introduce me as the owner and president of Video News and remind them of some of my many other stories. I’m not done. I also want to stop our discussions over prices. This will save time. So when I say a particular number is my lowest price, that is my lowest price and you can be sure I’ve arrived at whatever that number is very carefully. Now when I say I want these things I mean that I want them and I don’t want to have to ask again. And the last thing that I want, Nina, is for you to do the things I ask you to do when we’re alone together at your apartment, not like the last time.”

I mean, how are you NOT going to want to play that character if you’re an actor?

On top of the character stuff, this script is a great discussion companion for a previous article, The Six Types of Scripts Least Likely To Get You Noticed. One of those scripts I was trying to warn you away from was the coming-of-age story. However, I said if you refuse to listen and still want to write one, try to add a fresh angle to it. Don’t write the traditional coming-of-age story. Write something different.

Nightcrawler is exactly that. This is about a confused man who ends up finding his calling (coming-of-age). But he does it amongst a rocket-fast storyline and a unique subject matter we haven’t seen on screen before. Gilroy took a coming-of-age story and turned it into a thriller. If you are going to take chances and write stuff producers typically hate, the least you can do is that.

Gilroy did it and wrote a classic script in the process.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive (TOP 25!)

[ ] genius

What I learned: Characters whose demeanor opposes their desire can be quite fascinating. Lou is desperate to move up, yet seems completely disinterested whenever discussing so. He’ll blackmail you, but do so without the slightest hint of emotion. In other words, if you have have a character ordering a hit, have him laughing while he does it. If you have a character who’s steaming mad, have him deliver his side of the argument with a smile. That contrast never quite fits when we’re watching it happen and is therefore always engaging to watch.

My new best friend Sean and I are hanging out later. So I just wanted to post a picture of him.

My new best friend Sean and I are hanging out later. So I just wanted to post a picture of him.

One of the most frustrating things about going through all these scenes was reading scenes that just didn’t go anywhere. Nothing was happening. And here’s where you see a major difference between experienced screenwriters and new screenwriters. It’s the difference in their interpretation of the phrase “something happens.” In a script, in every single scene, in order to keep a reader riveted, something NEEDS TO HAPPEN. Beginner writers say, “Hey, that conversation between me and my co-worker about our douchey boss was kind of funny. I’ll put that in a script.” And they do. And they don’t understand why no one responds to it. It was cute. There were a few funny lines. And it was life, man! Real-world shit! The reason nobody cared is because nothing happened.

Experienced writers know that “something happens” means ratcheting up the stakes and bringing something big to the table, a scene where what people say actually matters, where there are consequences to people’s actions! If they’re going to write a scene about two co-workers, one of them is going to have a gun hidden in her jacket. She and her co-worker had an affair. He’s broken it off. She’s been e-mailing and texting and calling him to no avail. He barely responds to her. Echoes of Fatal Attraction. She’s finally convinced him to have lunch with her. She’s brought a gun to their little chit-chat and is considering using it if the conversation doesn’t go well. Now, something is happening.

There’s an old saying with writing screenplays. It goes something like this: Your story should be about the most important thing that’s ever happened to your character in his life. In other words, if what you’re writing about isn’t even the biggest thing that’s happened to your hero, why do you think we would be entertained by it? I think you can apply this approach, at least partially, to scene-writing. The scenes you write should be the biggest 1, 2, or 3 things that happened to your character that day. There will be exceptions to this for sure. But if you’re picking your best scene in the whole script? One that really shows off your chops? And it doesn’t even seem (or barely seems) like it was the most important thing that happened to your character that day? How do you expect a reader to be impressed?

But here’s the real killer. The writers who WERE able to write a scene where something was “happening?” The ones who avoided that pothole? They often made the mistake of writing the scene in the most predictable way possible. Those are some of the hardest scenes to read. Because here we are. This huge scene is laid out before us (i.e. Hero finally confronts his mother who left him as a child), and it… goes… exactly… according… to plan. He asks mom why she did it. She takes a deep breath. Says she doesn’t know. She thinks about it. Talks about how it was all too much for her. I mean, WE’VE SEEN THAT SCENE BEFORE! We’ve seen it a billion times.

I just don’t understand why screenwriters don’t realize this. Why they don’t realize that we’ve been down that road before. As a writer, it’s your job to know the reader’s expectations, and then go in a different direction. That way you surprise them as opposed to bore them. This to me, is what all the best writers do. And it’s one of the easiest skills to learn. You don’t have to be a master storyteller to do it. All you have to do is recognize the way a scene typically plays out, and go another direction. Even if that direction turns out to be a bad choice, at least we’ll applaud you for not taking the obvious route.

Another thing that shocked me is I don’t think I read a single “Hitchcock bomb under the table” scene out of all the submissions. Someone can correct me if I’m wrong (Miss SS read a few submissions so maybe she did) but I didn’t see one. This is one of the EASIEST ways to write a good scene. You should have 2-3 versions of this scene in every script you write. Maybe more depending on the genre. Essentially the idea is, if you have two people talking at a table, it’s boring. But if you tell the audience there’s a bomb underneath the table, a ticking bomb, then all of a sudden the scene becomes interesting.

This is where Sean and I met. Memories.

This is where Sean and I met. Memories.

You can apply this to a scene in a million different ways. I just did above. The two co-workers talking, one of them secretly has a gun they’re planning on using. That’s a Hitchcock scenario. The scene with John McClane and Hans on the roof in Die Hard. We know he’s the bad guy. John doesn’t. That’s a Hitchcock scenario. A 17 year old girl is going out with a 35 year old biker that nobody in her family likes. There’s a big family dinner. The girl and the guy are planning on dropping the bomb that they’re getting married. That’s a Hitchcock scenario. If you want to win a scene contest, write a good “Hitchcock scenario” scene and, at the very least, you’ll be in the running.

Not every scene has to be a world-beater. Comedy is different. As long as you’re funny, you can get away with not much “happening.” But you have to be a freaking dialogue master to pull that off. You have to write dialogue that SINGS. When you give your script out to people, you better always be receiving the compliments “Your dialogue was great” and “I couldn’t stop laughing.” If not, do not try to rest on your dialogue alone. But to be honest? Why not do both? Why not create those intense pressure cooker situations that make scenes pop ALONG with the comedy? That’s why Meet The Parents was so good. They did such a great job setting up the stakes of that dinner scene. With how much Ben Stiller’s character wanted to impress Robert DeNiro’s character (his girlfriend’s father). They made it clear that everything was riding on his performance at that dinner table. So each word spoken was a potential death trap. Then, when they’re bantering back and forth about whether cats have nipples, it’s not just the writer trying to show you how funny he is. It’s Ben Stiller’s character digging a hole the size of the Grand Canyon trying to find a way out of his continued screw-ups. When we’re emotionally invested in a scenario, we’ll always laugh more.

Despite my passionate plea for better material, this week was really cool for me because I usually read everything within the context of the script. This placed my focus SOLELY on the scene. The scene had to live or die on its own. And it made me realize that each scene, in its own way, is like a script. It’s got its setup, its conflict, and its resolution. It needs goals, stakes, and urgency. It needs conflict. But most of all, it needs to matter. We need something important to be happening or else we’re going to tune out. And you guys need to treat it like that. Treat every scene with pride, like it’s its own story, and try to write the best story you possibly can. If you do that, the next time I hold one of these contests, you won’t have to choose a scene from your script. Because every one of them will be great.

Genre: Comedy

Premise: (from me – based on limited info) A frustrated middle-aged family man who hates dealing with all of life’s bullshit finds out about a man who solves people’s problems by jumping into their minds. He enlists this man to eliminate the problems in his life, with unexpected consequences.

The Setup: JIM (our schlub) hates his job, his marriage, his life – he’d rather just avoid everything. So when he meets a guy in a bar who gives him a number of another guy – BOB – who can help him do just that, Jim is intrigued. He calls the number, and this mysterious, intimidating Bob character tells him to be at his place in one hour. Here’s the scene that follows…

Writer: Ethan Furman

Details: 7 pages

I think people outside of Los Angeles believe that we Los Angelinos walk around bumping elbows with celebrities all day. You take your dog for a walk, there’s Tom Cruise grabbing a hot dog at Pink’s. You grab a bite at Chipotle, oh, there’s Angelina Jolie, complaining about the lack of guac on her burrito bowl. And when you get home, Ken Jeong is sitting on your steps practicing new characters via Skype with Bradley Cooper.

Sadly, celebrity sightings are few and far between unless you’re one of these obsessive stalker types who go to all the events and track their celebrity buddies’ whereabouts on Twitter. But if you’re just walking around randomly, you ain’t going to see many celebs. So when you DO see someone big, it’s kind of cool. And today, for the first time in a long time, I had a celebrity sighting, and it was awesome.

The setting? El Carmen. A pleasant Mexican dive bar/eatery. There were a total of 10 people in this bar. And then who walks by? Just marching forward like it’s nothing? Sean Penn! Sean fucking Penn. And let me tell you this: This guy looked like just as much of a badass as he does in the movies. He slid into a back booth with some ladies he was (I’m guessing – but who knows, since it’s Sean Penn) meeting there. I think the reason it hit me so hard was because it was such an empty place. And so it’s odd to spot a big celebrity around no other people. It just feels off. Like a crew of 50 people should be following him around or something. Anyway, it was rad.

What does this have to do with Scene Week or today’s scene? ABSOLUTELY NOTHING! I just wanted to tell you my cool Sean Penn story. And now that I think about it, it wasn’t that cool at all. I just saw a man walk by me. It would’ve been a lot cooler if I had tried to talk to him and got decked in the face. I’ll try that route next time.

So, what’s today’s scene about? Glad you asked. Our hero, Jim, comes to this guy Bob’s house. As he walks in, hookers stumble out. When he gets to the living room, Bob’s playing a grand piano in shorts, snorting coke. After Jim’s WTF reaction, Bob asks him why he came. Jim tells him he has to fire a guy at work that he likes and doesn’t want to do it. Bob responds by explaining to Jim his super-power. He can jump into people’s minds! That means Bob can jump into Jim’s mind, fire his friend at work, and an hour later, Jim won’t remember a thing. He can continue on with his life guilt-free. Hesitant at first, it’s clear that Jim is intrigued. Let the craziness begin!

Okay, so what’s so great about today’s scene? Well, here’s the thing. This kind of scene, in my opinion, is the easiest kind of scene to write. It’s the “Premise” scene. It’s when you essentially reveal the concept and hook of your story. And in that sense, it begins the story. Because once your hero is introduced to this moment, the train starts moving.

So in that sense, Ethan kind of cheated. There is no subtext here. There are no twists. There’s no dramatic irony. There’s nothing in this scene that’s difficult to do and shows skill. But here’s the reason I included it. Out of all the scenes I read this week, it’s the only one that inspired me to want to read more. I thought this was a pretty nifty concept and one I hadn’t seen before. I wanted to know what would happen when this guy entered our hero’s head. I could see the story possibilities flow. One hour, your life is fine, then you wake up an hour later and everything in your life is backwards. Or Bob screws up the first time, has to mind-jump again to fix it, messes up even more, tries to fix it again, keeps making it worse. You could do a lot of stuff with this premise.

But let us get back to the actual scene. Just because Ethan picked the easiest kind of scene to write doesn’t mean it’s guaranteed to work. I’ve seen thousands of easy scenes get screwed up. In any scene, it comes down to one thing: Are you interested in the characters and what they’re dealing with? If you’re not, the scene isn’t going to work no matter how well it’s written.

I liked Jim. His situation is relatable. And I thought Bob was fun (as well as mysterious). I liked how he used to be an Olympic athlete. I liked how he was casually playing the piano when Jim walked in. I thought the hookers and the cocaine were a little cliché, but they were organic to the character so I went with it.

Assuming you’ve got the character issue taken care of, the next step with a scene like this is dialogue. While I’m not going to say this dialogue was amazing, the combination of it and the intriguing premise was enough to keep me entertained. I will say I like when characters are played against type – when their actions and disposition don’t match up with the way they speak. And we get that with Bob, who’s presented as kind of a wild guy, yet is really smart and on point when he speaks.

“Well, enough with the engaging small talk, Jim. You’re here because you have a problem.” “Um. Yes. I do.” “And what is the nature of this problem?” “Well, uh, specifically, my boss is making me fire my assistant.” “And why is that a problem?” “Well…I like him a lot. I feel sick about it.” “Ah. So you weren’t being specific.” “Excuse me?” “You said your problem was that your boss is making you fire your assistant. But in reality, the specific problem is that it makes you sick to do it. It’s something you don’t want to do.” “Yes. I guess that’s right.” “Yours is a problem of guilt. Guilt makes us feel bad. Hurting someone – firing your assistant, breaking up with your girlfriend – these things must be done sometimes. But the guilt is very unpleasant. Correct?”

That sort of unpredictability, of Bob seeming like a doofus then showing he’s quite intelligent, in combination with the suspense of finding out what it is Bob does… that kept me invested.

I also liked how Ethan anticipated expectations and flipped them on their head. Bob: “Here’s what’s going to happen, Jim. I’m going to explain what it is I do. You’re not going to believe me. Then there will be this little back and forth about whether I’m crazy, full of shit, et cetera. I like to skip over that part, because it bores me, so we can just get down to the business of solving your problem. You with me?” It was lines like this that, again, kept me intrigued.

I think my only suggestion for Ethan is to shorten up the scene. Whenever you’re dishing out exposition, even if it’s fun exposition (that’s what I call premise exposition, since it’s usually the fun part of the script, unveiling the premise on the audience), you MUST BE AS SUCCINCT AS POSSIBLE. Because no matter how interesting the exposition is, if the reader feels like they’re being talked to for too long, they start getting bored. And after the “climax” of this exposition, Bob revealing how this whole mind-jumping thing works, I didn’t have enough energy left to listen to Jim’s query (“If your mind is in my body, then where does my mind go?”). The answer with the “mind spa” stuff was cute, but again, you gotta know when you’ve hit your scene’s climax and then get out. It’s like the end of Rocky. The fight’s over. We don’t need to see Rocky shower.

As for what you do with that extra exposition, which might be necessary, is you just put it in a later scene. For example, right before they’re about to mind-jump, Jim can realize: “Wait a minute! What happens to my mind while you’re inside of me??” And Bob answers the question then.

So yeah, I liked this. Again, it had some cracks, like all the scenes this week. But it passed the biggest test of all. After I read it, I wanted to read more. What did you guys think?

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Avoid the cheap jokes. The gay jokes. The hookers. The coke. Those are cheap laughs. And what I mean by that is, you’re going to get a laugh from some readers, but it will be a hollow laugh. If you can find a new angle on one of these jokes though – a way to make it fresh, then by all means use it. For example, I read a script once where gays were discriminating against a guy for being heterosexual. It was a clever 180 on a tired joke so it worked. Just know that the cheapest jokes – they’re the ones readers see ALLLLL THE TIME. And if you’re a good writer, you don’t want to be like everyone else. Do you?