Genre: Comedy

Premise: When a failing TV writer sees his friend, Charlie Kaufman, become a screenwriting mega-star after his indie hit, “Being John Malkovich,” he decides to kill him.

About: While there have been rumors that Charlie Kaufman wrote Killing Charlie Kaufman under the pseudonym “Wrick Cunningham,” those rumors have been confirmed to be false, as Charlie Kaufman’s people themselves wrote to tell me that that’s not the case. As for what that means on who did write “Killing,” who knows? It could be anyone who’s a Charlie Kaufman fan.

Writer: Wrick Cunningham

Details: 112 pages – March 5, 2002 draft (1st draft)

Rick Cunningham is on suicide patrol – for himself. He’s got a wife he doesn’t really like. Kids he can’t support. He’s a writer but his agent barely talks to him. Therefore he’s decided life isn’t worth living anymore. That is before he gets a surprise phone call that he’s been invited to work on the Donny Most show, a sitcom centered around a comedian named Donny Most.

The staff is a little surprised to find out Rick’s never actually worked on a TV show before. In fact, Rick doesn’t even WATCH TV. But gosh golly gee they sure do like making fun of his name (Richie Cunningham?). People like to ask him how the Fonz his doing. If he’s talked to Ralph Malph lately. It drives Rick nuts. But at least he’s getting paid to write.

That is until an unfortunate accident. While pulling out from a parking space after work, Rick accidentally RUNS OVER Donny Most, the star of the show! The injuries are enough to put Donny in the hospital for months, which means the show is cancelled! Which means all those writers are out of jobs. Which means they all HATE Rick.

Well, all except for one. Another writer on the show named Charlie Kaufman can’t thank Rick enough. He HATED working on Donny Most and the cancellation has given him new life. In fact, it means he can finish this passion project of his, a feature script called, “Being John Malkovich.” Rick thinks the idea is way too bizarre but encourages Charlie to stick with it. Who knows, it might make a great writing sample someday.

Meanwhile, Rick’s career starts tanking even more spectacularly than before. Everyone in town thinks that he killed Donny Most (even though he’s fine – just injured) and therefore won’t hire him for anything. On top of that, Rick gets word that his old friend Charlie sold that crazy John Malkovich script. And even more surprisingly, Malkovich, the actor, is doing it! Hmm, he figures, that’s nice. Too bad it will only make 10 bucks at the box office.

Malkovich ends up making more than 10 bucks at the box office. In fact, the success of the film launches Kaufman into the screenwriting stratosphere. Everyone wants to be in the Charlie Kaufman business. For some reason this devastates Rick, who ends up joining a “We Hate Charlie Kaufman” support group, made up of people who have known Kaufman at one point or another and now want to kill him. In fact, the focus of the group is offering up dream scenarios in which they kill Charlie is bizarre and violent ways.

Pretty soon, Rick wants to kill Charlie too. He’s convinced that Charlie’s responsible for his dying career. So he goes and buys a gun and starts prepping for the murder. In the meantime, a new pill comes out that allows you to feel exactly like a Charlie Kaufman movie – both happy but also a little bittersweet. People in the group start taking the pill and find happiness in being able to feel like Charlie.

Rick gets distracted when an updated “Happy Days” show gets ordered and they want him to work on it. They think it’s hilarious that a writer named Rick Cunningham would be on the writing team. Rick finds his way back to a good place and decides to re-distribute his anger into writing a script about how he wants to kill Charlie Kaufman. Once finished, he sends it to Charlie, who loves it! He wants to make it. Which would be great except Rick falls into a coma (after getting shot by Donny Most, who was pissed off that Rick ruined his career)!

Then (of course) after he awakes, he falls into ANOTHER coma! And when he awakes, he finds out he’s been taking the Charlie Kaufman pill, which has made him believe he’s Charlie Kaufman. Which means that it wasn’t Rick who wrote “Killing Charlie Kaufman.” It was Kaufman himself! Kaufman tries to explain all this to Rick (or is he explaining it to himself?) as Killing Charlie Kaufman becomes a giant hit starring Tom Cruise as Charlie Kaufman. Uhhh, confused yet? Yeah, me too. Then again, would it be a Charlie Kaufman script if you weren’t?

Okay, lots to say about this one. Let’s start with the first act. Rick Cunningham starts off miserable. He’s already in a bad place. He already wants to kill himself. Therefore, when Charlie starts doing well and Rick becomes miserable, I had a hard time accepting that he’d pin all this on Charlie. He was no worse than he was a few months ago. I thought the script would’ve worked better if it had started out with Rick at the top of his career. He was kicking ass in the TV world. He was on his way to becoming one of the top writers in the business. Maybe the Donny Most Show was actually his first show-runner job. Things were looking up.

Then Charlie Kaufman ruined this somehow and went on to become famous. Actually, that was another beef I had. I couldn’t figure out why Rick was so upset with Charlie. The two were friends. Rick encouraged Charlie to pursue the Being John Malkovich script. Why would he want to kill him after he became successful with it? It wasn’t like Charlie screwed him over or was a dick to him. He simply became successful.

The script probably needed Charlie to be more of an asshole or screw Rick over in some way. There needed to be a moment where Rick could’ve submitted his weird quirky script to one of the producers of the show, but decided against it cause he felt it would go nowhere. Charlie then did instead, which led to his career skyrocketing. In other words, Rick could’ve had this life himself, and he feels Charlie stole it from him. Then it would sort of make sense why he’d become obsessed with killing him. As it stands, I didn’t understand the hate.

Then, when we get into the Charlie Kaufman drug and the producing of Killing Charlie Kaufman, things start to get weird. Like, really weird. It’s always tricky when you have a screenplay mostly grounded in reality then try to throw in a dose of fantasy – such as the Charlie Kaufman pill. If there’s anyone who can pull it off, it’s Kaufman, but I had trouble wrapping my brain around the pill and what was going on with it. It felt a bit too “out there.”

And of course I hate wrapping major plot points around murky story elements. At first the pill appears to be a joke, something to talk about during the group therapy sessions. But then it becomes an essential part of the story, with Rick starting to believe he’s Charlie (or something) and writing a script under Charlie’s name, which is actually under Rick’s name, which is actually a pseudonym for Charlie, which is actually written in real life by “Wrick Cunningham,” who is of course Charlie Kaufman.

When you’re trying to pull shit like that off, you have to make sure the edges are as sharp as can be. And they weren’t, often leaving me wondering what the heck was going on. You could read me the section where Kaufman explains to Rick how Rick thought he was Charlie when he wrote the script a million times over and I still wouldn’t get it.

You know, I originally wrote this review thinking it was written by Charlie Kaufman. I don’t know what to make of it now being written by some other completely random person. I mean, it would’ve been pretty cool if Kaufman orchestrated the whole facade and a totally Kaufman like thing to do. But I guess we’re just left with a really big fan of Kaufman who sorta kinda sounds like him and has too much time on his hands. Regardless of who wrote it, it didn’t really click. This one wasn’t for me.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Avoid wrapping major plot points around confusing or murky story elements. We’re not really sure what these “Charlie Kaufman pills” are or how they work. So when the final act consists of our protag “becoming” Charlie Kaufman and “sorta” writing this script as Kaufman since he was on the pills, we’re just confused.

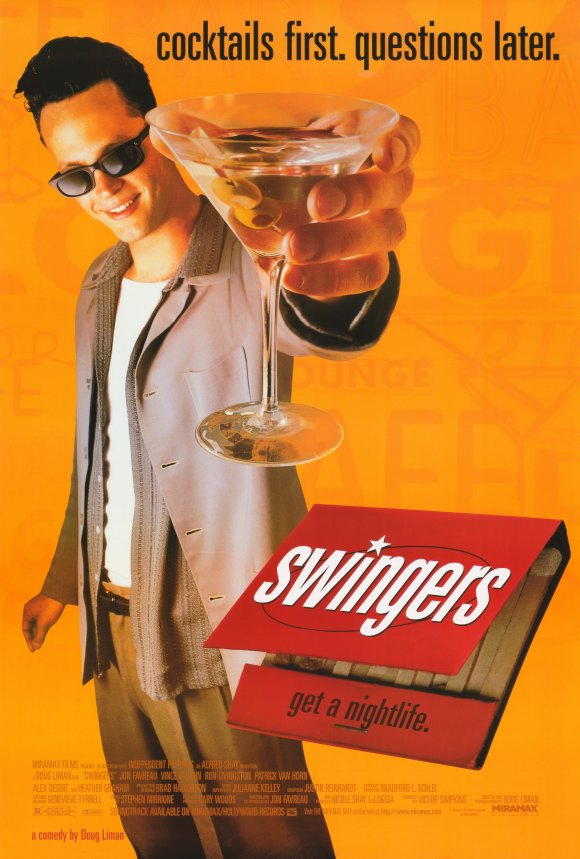

Swingers is a fascinating pastiche of a movie. Its well-chronicled history includes the actors doing years of table reads to drum up interest and funding for the movie. It was eventually shot on the tip of a shoestring with Doug Liman (The Bourne Identify) directing the film. It was a box-office dud, but word-of-mouth made it a DVD sensation. It started Vince Vaughn’s career and eventually led to John Favreau becoming one of the top directors in Hollywood. Script-wise, it’s basically a laundry list of things I tell you NOT to do. You know I hate scripts with “guys talking in rooms.” Well, this script is basically one revolving room with characters talking in it. Goal-wise, there isn’t much there. I guess you could say the goal is for Mike (Favreau) to get over his ex-girlfriend. The script sends its characters off to Vegas, where we assume the remainder of the story will take place, only to send them back to LA twenty minutes later – leaving us confused and disoriented. You know how I hate Woe-Is-Me characters? Well Mikey is the quintessential woe-is-me protag. On top of this, the script is one long string of dialogue. It’s a non-stop talkfest. So why does it all work? Well, that’s hard to say. I have a saying: “Funny trumps everything.” Even if you break every rule in the book, if the audience is laughing, they’ll stick with you. And the dialogue in Swingers is realllllyyyyy funny. Still, this is one of the trickiest scripts I’ve ever broken down. It shouldn’t work. It has no business working. And yet it does. Let’s see if we can’t find out why.

1) The Sympathy Card – One of the reasons we love Mike despite how pathetic and depressed he is (Woe-is-me!), is because he’s earned his “sympathy card.” Give your protag a sympathy card by having something bad happen to him. Two of the most popular ways to do this are through the death of a loved one or getting dumped by your significant other. If you show how devastated your protag is, we’ll have sympathy for him and follow him through anything. Mike’s obsessive yet honest depression resulting from his girlfriend leaving him ensures we’ll be Team Mikey all the way.

2) For good dialogue, give each character a directive in the scene – When bad writers try to ape a movie like Swingers, they focus their scenes on “humorous” observations about life with no real focus or structure (i.e. they’ll have their characters discuss for seven minutes why they believe Dr. Seuss was gay). For dialogue to work, the scene needs to have direction. You achieve this by giving each character a directive they’re trying to achieve. You then look for humor within the evolution of that discussion, as opposed to trying to find the comedy first and building a scene on top of that. Look no further than the very first scene in Swingers to see this in action. Mike is talking to his friend Rob. His directive is to figure out if it’s okay to call his ex. Rob’s directive is get Mike to stop thinking about his ex. It’s a simple and humorous discussion, anchored by both characters having clear directives in the conversation.

3) CONFLICT ALERT – Remember guys, movies rarely work unless there’s some element of conflict between the two leads. If the characters are always on the same page, we’re going to be bored! Mike is all about respecting girls and being honest. Trent is about telling girls whatever he needs to to get them in bed. He has no respect for them. This is the basis for 75% of their conversations. They always butt heads on this issue. That push and pull is what makes their dialogue so fun.

4) Disagreement Is A Comedy’s Best Friend – There isn’t a single scene in Swingers where characters agree. Every scene is two people disagreeing about something. It’s that simple. The intensity of these disagreements varies. But it’s always there. The first scene has Mike and Rob disagreeing about whether he should call his ex. The second scene has Trent and Mike disagreeing on whether to go to Vegas. The blackjack scene has Trent and Mike disagreeing on whether to double down. Then Mike and Trent disagree on how to treat a waitress. In the girls’ trailer, Trent wants to hook up with a girl while Mike wants to check his voicemail to see if his ex called. It’s one of the simplest ways to create comedy people. Just have people disagree.

5) If your plot is all over the place, make sure your protag’s throughline is strong – Like I mentioned in the setup, this plot (when there is one) is all over the place. We start in LA, then Trent convinces Mike to come to Vegas, then we come back to LA, then we start randomly going to clubs and parties, then there’s a weird showdown with a group of gangbangers, then we go back to the bar scene. There’s virtually no plot here! However, the reason the movie’s able to stay together is because Mikey’s throughline is so strong. He is OBSESSED with his ex. He’s obsessed with if she called. He’s obsessed with whether he should call her. The first two scenes (the first with Rob and the second checking his answering machine) barrel home the issue that Mike is not over his girlfriend. This issue is a part of every single scene, which saves this script from wandering aimlessly into the Nevada desert.

6) STAKES ALERT – Remember guys, heighten scenes by setting up the stakes AHEAD OF TIME. One of the reasons the classic blackjack scene works so well is because we establish beforehand (in the car ride) that Mike only has $300 bucks to his name. Therefore, when he accidentally gets stuck at the high roller table (100 dollar minimum), and has to double down (so the bet is $200), we know this is 2/3 of all the money he has. The stakes for winning this hand are now HUGE. Had we not established this beforehand, this scene wouldn’t have played nearly as well.

7) SMASH CUT TO – The “Smash Cut To” has sort of been forgotten but is still a viable alternative to “Cut To” that can be used for comedic effect. Use it any time you’re cutting to another scene that’s the payoff of a joke. For example, when Mike and Trent are arguing on the phone about going to Vegas and Mike keeps saying, “I’m not going to Vegas.” “We’re going to Vegas.” “I’m not going to Vegas.” “We’re going to Vegas.” “I’m not going to Vegas.” “SMASH CUT TO: Mike and Trent in car going to Vegas.” Or after Mike’s been wiped out at the high stakes blackjack table. “SMASH CUT TO: Mike and Trent are wedged between the BLUEHAIR and the BIKER at the FIVE DOLLAR TABLE.”

8) Use friendship to make an asshole character likable – Trent is a huge asshole. He’s selfish. He’s a dick. He has zero respect for women. He makes jokes at others’ expense. So why do we like him? Because Trent would take a bullet for Mike, our protag. You have no doubt, in any scene, how much Trent loves Mike. It’s that love, that friendship, that helps us overlook all those negative traits. If Trent was as much of a jerk to Mikey as he was to everyone else? We’d hate him.

9) Milk your characters’ dominant traits for better dialogue – Whoever your characters are, particularly in comedy, look for any way to milk their dominant traits within the dialogue. Mike’s dominant traits are his lack of confidence, his nervousness, his indecisiveness. So whenever Mike talks, he’s always stuttering, repeating things, overcompensating (He bumbles to the dealer at the high stakes table. He bumbles to the girls they meet at the Vegas bar). Trent, on the other hand, loves himself. So a lot of his dialogue is in the third person (“Daddy’s going to get the Rainman suite.” “Now listen to Tee. We’ll stop at a gas station right away.”). So many writers write friends who sound the same. This is one of the easiest ways to make them sound different.

10) The Choice – Remember, the most emotionally gripping scripts have “The Choice” at the end. That’s when your main character has a choice he must make near the end which is directly related to his flaw. Swingers does a great job of this. Mike’s flaw is that he can’t move on from his girlfriend. So in the end, his ex-girlfriend calls, and then on the other line, the girl he met the previous night calls. He literally has the choice of a) talking to the new girl (and therefore overcoming his flaw), or b) talking to his ex (failing to overcome his flaw). He of course chooses A and we’re happy because Mike has finally changed!

These are 10 tips from the movie “Swingers.” To get 500 more tips from movies as varied as “Aliens,” “When Harry Met Sally,” and “The Hangover,” check out my book, Scriptshadow Secrets, on Amazon!

This film starts off pretentious, covering bases already covered in tons of previous flicks, then takes a right turn and morphs into a nasty good thriller.

Genre: Thriller

Premise: After her husband is released from jail for insider trading, a young woman is prescribed a new medication to treat her anxiety. However, the pill ends up having some seriously dangerous side effects.

About: Back in 2011, Steven Soderbergh was putting together a movie with Warner Brothers called “Man from U.N.C.L.E.” When they wouldn’t get him the budget he wanted, though, he took his writer, Scott Burns, and came up with Side Effects, a script previously titled, “The Bitter Pill.” Burns scripted a couple of other Soderbergh films – “The Informant!” And “Contagion.” Side Effects came out this weekend and stars Jude Law, Channing Tatum, Rooney Mara, and Catherine Zeta-Jones.

Writer: Scott Z. Burns

Details: Movie was 106 minutes. November 22, 2011 draft was 123 pages.

I keep hearing that Steven Soderbergh is going to retire, yet I keep seeing Steven Soderbergh movies whenever I go to Fandango.com. Haywire. Magic Mike. Now Side Effects. Haven’t those all come out in the last year alone? If Soderbergh’s so sick of directing, why is he directing more movies than anyone in Hollywood?

Soderbergh’s kind of a bizarre director anyway. Here’s my main beef with him. He never stokes the fire in his movies. He always keeps a nice steady burn, enough for you to stay warm, but he never burns you. He never turns up the heat all the way. For that reason I always leave his films feeling unsatisfied. Bubble is the perfect example. Nothing that dramatic happens in the movie. It just kind of keeps your hands warm. I suppose some people like that but I’m not one of them. I need things to HAPPEN in my movies. I need plot points with some weight, twists with some edge, I need moments that burn you.

What irks me about Soderbergh is that he seems to think his unique approach to filmmaking makes up for this. He was one of the first guys to start using hand held all the time. He’ll shoot movies in black and white. He’ll cut scenes with dialogue that’s laid over from other scenes. To me, these are distractions. You can argue that they spice up the viewing experience, but in my opinion, if you tell a good story, you don’t need all these little tricks.

Emily Taylor’s had a tough few years. Her husband, who she’d been sharing the Manhattan high life with, was thrown into jail for insider trading. She stood by his side during his incarceration, but now that he’s out, she realizes that she’ll never have the same life again. They’re going to be living in a 1000 square foot apartment instead of the 10,000 square foot one. They’re going to be eating at home instead of at the Gramercy Tavern. True, it still ain’t that bad, but when you’ve been to the top, falling back to earth can be devastating, and that’s where Jonathan Banks (Jude Law) comes in.

Emily is referred to Jonathan for her anxiety and depression. He prescribes her a new medication called Ablixa. The pill does wonders, improving her sex life, improving her mood, improving her energy. It’s like a 180 degree turnaround. But it does have some side effects, the worst of which puts Emily in a zombified state. She’ll wake up at weird times during the night and make dinner. Or she’ll stare off into nowhere for extended periods of time.

The side effects are annoying but ultimately harmless, so when Emily begs to stay on the pill, Jonathan reluctantly allows it. That turns out to be a not-so-good call though because (major spoiler) a few nights later Emily stabs and kills her husband while sleepwalking. Uh-oh.

At first this appears to be an open-and-shut case, but as the lawyers and media swarm in, Emily begins to get painted as a victim of the U.S.’s over-dependence on prescription pills. It’s the medication that made her sleepwalk, that was responsible for her husband’s death, not her. And, of course, this puts Jonathan front and center in the media spotlight. Why did he prescribe her this pill for which so little was known? Why did he continue to allow her to use it despite the excessive sleepwalking side effects?

Pretty soon Jonathan is losing his sponsors, losing his colleagues, losing his wife and in danger of losing his job. Desperate to get his reputation back, he contacts Emily’s old doctor, Victoria Siebert (Catherine Zeta-Jones) to get more info on Emily. (major spoilers) Victoria paints Emily as your average depressed young woman, but the talk inspires Jonathan to look deeper. And what he finds, surprisingly, are some inconsistencies in Emily’s story. One of her supposed best friends at work doesn’t seem to exist. And an earlier suicide attempt in her car was prefaced by her putting on her seatbelt.

Could it be – gasp – that Emily deliberately killed her husband? Could it be she planned all this from the beginning, the fake side effects, the fake sleepwalking, in order to get away with murder? And how come Victoria made a huge stock bet that Ablixa would tumble mere days before the murder, ensuring she’d get a ton of cash if the stock tanked? Jonathan’s asking all these questions, but not getting simple answers. Is he so desperate to get his life back that he’s no longer able to see reality? The answer to that question will determine the rest of his life.

There are a couple of ways you can take a story like this. You can go the debate route or the dramatic route. The debate route is where you tackle all sides of the debate – essentially whatever your theme is. So here the theme appears to be, “Who’s really responsible for a side-effect related drug accident?” Is it the person taking the drug? Is it their doctor? Is it the makers of the drug?

I HATE debate-oriented screenplays. Actually, let me take that back. I hate when the debate is the ONLY THING GOING ON IN THE STORY. Ignore drama. Ignore story. Just debate an issue that has no obvious answer. It’s been awhile since I saw it, but I remember Syriana to be like that. It was less about a story and more about debating who’s responsible for fighting oil-motivated wars. Screw that. I want a story. I want clear villains to emerge. I want the people responsible for bad shit happening to go down. I don’t wanna feel like we’re just here to talk about the issue. Cause I can do that with my friends. When I go to a movie, I want to be entertained.

(spoiler) Which is why I was sooooo happy when Jonathan started suspecting Emily was lying – when we found out she put her seatbelt on before trying to kill herself, when he started catching her in little lies – It’s then when I sat up and said, “Oh my God, she murdered her husband on purpose!” Gone were the debates, replaced by good old-fashioned DRAMA. A goal arises (Jonathan has to prove Emily killed her husband). Obstacles arise (he loses his family, his job, people try to stop him). Reversals occur (we thought Victoria was good. Turns out she’s in on it). I understand there’s a certain “adult-ness” and sophistication to watching a movie that simply debates an issue. But fuck that. If I’m paying 15 bucks, I want interesting shit to happen.

Something else that popped out at me was how each of the three major roles allowed the actors to play two completely different types. Jude Law starts off playing a normal helpful engaging psychiatrist. Then later, he’s a wild crazed desperate man. Rooney Mara starts off playing this dazed depressed victim sleepwalking through life. She then turns into an evil cunning man-eater. Catherine Zeta-Jones starts off as a straight-laced respected doctor, then turns into a backstabbing cold conspirator. You HAVE to think about this stuff when writing your script. It’s how you get good actors attached. Actors mean financing and financing means your movie gets made.

Another thing I noticed was that we switch protagonists midway through the story (talk about a midpoint shift!). Rooney Mara (Emily) is our main character when we begin. She’s the one dealing with her husband being released from jail. She’s the one seeking help. She’s the one we’re focusing on in relation to the medication. However, after the murder, the script moves over to focus on Jude Law’s character (Jonathan). It was done startlingly naturally, so much so that you barely noticed it. But don’t let that fool you into thinking it’s easy to pull off.

From a story perspective, it was necessary. That’s because once Emily goes to jail, there’s no need to stay with her anymore. Everything interesting about her character from this point on is a secret (that she’s faking this). It’s more dramatically compelling, then, to switch over to Jonathan, who’s experiencing a free-fall in his profession, something that’s way more interesting to watch than a girl sitting in a jail cell. So that was a clever little move by Burns, yet still something I would avoid unless you’ve written 20+ scripts. I’ve seen amateur writers try to do something similar and the result is random as hell. We’re sitting there going, “Why are we watching this other character now? I don’t understand.” Burns worked Jonathan into the story bit by bit, increasing his presence as we approached the midpoint, so that by the time Emily went to jail, we knew Jonathan well enough to let him take the reins.

That just proved how skillfully Side Effects was written. I don’t know if anyone’s going to remember it later in the year, but it’s a strong film that’s worth seeing. The only real issue I had with it was that it oozed this depressing tone. You don’t feel good when you leave the theater afterwards. It takes something out of you. Either way, it’s the best script Soderbergh’s had to work with in awhile. That alone should be reason to check it out.

[ ] what the hell did I just see?

[ ] should’ve gone to In and Out instead

[xx] worth the price of admission

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: YOU NEED CHARACTERS THAT ALLOW ACTORS TO SHOW THEIR RANGE. Make sure they get to play at least two different types, like Side Effects does.

Do you feel overlooked? Do you have an amazing short you believe I didn’t see the brilliance of? Want to prove it? Well, here’s your shot. For anyone who submitted a short script that did not get reviewed, feel free to pitch it right here in the comments section and post a link to your short. Maybe I missed a few good ones. Or maybe someone here can tell you why your short wasn’t up to snuff. Excited to see how the discussion goes. Time to play!

Shorts Week: Welcome to the final day of Shorts Week, where I’m covering 5 short scripts from you guys, the readers. Shorts Week was a newsletter-only opportunity. To sign up and make sure you don’t miss out on future Scriptshadow opportunities, e-mail me at the contact page and opt in for the newsletter (if you’re not signed up already). This week’s newsletter went out WEDNESDAY NIGHT. Check your spam folder if you didn’t receive it. If nothing’s there, e-mail me with subject line “NO NEWSLETTER.” The next newsletter will go out this Saturday night.

Genre: Family/Fantasy

Premise: Set in the 1950s, a young boy builds a jerry-rigged spaceship to rescue the Sputnik dog he believes the girl of his dreams has lost.

About: We have an Aussie writer here. But don’t call him by his real name, Dean. He only answers to Mr. Spleen!

Writer: Mr. Spleen (Dean Friske)

Details: 25 pages

Okay, so Shorts Week is coming to a close. What have we learned from this week? Hmmm, shorts are good for showing and not telling. Don’t write a short dealing with mundane everyday activities or everyday conversations. Shorts need to stick out and get people’s attention and that means thinking big. There are two types of shorts. TRUE shorts (10 pages or under) and SHORTS PLUS (10-30 pages). I wish I could’ve made the distinction ahead of time. A nice twist or “button” at the end of a short is encouraged, as it leaves the script with a pop.

I would add not to let low/no budget issues deter you from writing an exciting short. There’s this belief that if you don’t have a lot of money, you can only shoot a quick dialogue scene between two actors. And that’s the problem. No matter how you spin it, now matter how many times you hand out your link with the warning, “Now remember, we didn’t have a lot of money,” your short will always be considered just another “couple guys in a room talking short” and those bore the shit out of their audiences. Use time travel (cheap to shoot – i.e. Primer), cloning (cheap to shoot), teleportation (cheap), zombies (inexpensive make-up), use amnesia or danger or intense situations – anything you can think of that carries with it a “must-see” quality that can still be shot on the cheap. Above all, try to be original. Just like a feature script, readers respond to material that beats uniquely, whether that uniqueness comes from the concept, the execution, the writer’s voice, or all of the above. If you achieve a combination of any of these things, your script is going to feel fresh. Which is the perfect segue to Lost Dog!

It’s 1950s suburban America. It’s a time of optimism, the Golden Age of the American dream. About the only thing America doesn’t have going for it are those pesky commies, who they’re going head to head with on all things technology, the most important battle of which is space travel. It seems the Russians have beaten the Americans into space, launching the world’s first orbiting satellite, Sputnik, “manned” by the planet’s first astronaut, a dog!

Back on earth, we meet Davis, 10 years old going on 40. Davis is an inventor-in-training, and just now getting the fever for the opposite sex. And there’s one particular object of his affection – Carol. She may be 10, but you can tell this girl is going to be breaking hearts well into the second half of the century. And she’s getting started today.

UNLESS!

Unless Davis can somehow impress her. And what do you know, the perfect opportunity arises when Carol loses her dog. She’s got fliers up all over the neighborhood and when Davis sees one, he notices the dog bares a striking resemblance to the one they’ve shown on TV, the dog in Sputnik!

So Davis enlists the help of his neighbor and best friend, Emily, who he’s unaware is secretly in love with him, to help him get to Sputnik and rescue the dog. She’s reluctant at first, seeing as the whol point of this is to snag homewrecker Carol, but she likes Davis so darn much, she agrees.

The two – who are the most kick-ass team ever – create a shuttle via an elevator and a bunch of covertly rigged rubber-bands. They’re shot up into space without a hitch and once there, Davis has only a tiny window to space-walk over to the Sputnik satellite, grab “Carol’s Dog,” get back to their shuttle, and return to earth.

This process does not go smoothly, but Davis does get the dog and the two go shooting back down to earth, crash-landing in their town’s main park, the exact park where Carol happens to be playing.

With. Her DOG.

Yup, Carol’s found her dog. Which means that dog Davis spent so much time saving is, uh, not Carol’s dog. Devastated, Davis realizes he might not ever get the girl of his dreams. That is unless he sees that the girl of his dreams has been right under his nose this whole time.

Let me count the ways in which I love this script. I love how it’s set in the 1950s, giving it a classic vintage charm. I love how our two main characters are kids. I love how one of them is secretly in love with the other. Conflict. Dramatic irony! Dialogue that’s always charged. I love the whimsy of it all. I love how two kids develop a device to travel into space in a way that only kids can. I love the ingenuity and cleverness of all the details – using thousands of rubberbands to launch the elevator, using hair spray to steer in space. I love the immediacy behind everything (they only have 3 minutes once they’re up there to do the job). I love that it’s all built around a personal core (this is really about two friends). I love that you can’t help but wonder what Michael Gondry or Spike Jonez would do with this.

Having said that, there are parts of the script that were too loosey-goosey for me. And I’ve already spoken with Mr. Spleen about them. The set-up and payoff of the bullies is weak. Their storyline is too separate from the main plot (their big scene is attacking Davis in the school bathroom). With how irrelevant their actions are, you wonder if they should be in the script in the first place. That’s something you never want to forget. Only create subplots if they’re an intricate part of the main plot as well. For example, if these bullies found out about Davis and Emily’s plans and tried to sabotage them, now they’re an actual part of the story. Their actions have an effect on the plot. We’d also, then, want their storyline to be paid off. We’d want to see them go down. As it stands, with them bugging Davis in the bathroom for reasons that have nothing to do with anything else, we just don’t care.

Then there’s the guy they buy their parts from. There’s something not quite right about the sequence, although I’m not sure what it is. The character doesn’t feel fully formed or something.

On top of that, some of the dialogue could be worked on. At times it’s good but other times a little confusing. For example, early on Davis invites Emily to the park via his preferred communication method, a paper airplane note. When she gets there, he’s hiding out, staring at Carol from a distance. Emily’s first words are, “Carol?” Now after you’ve read the script, this line sort of makes sense. Emily’s saying, “You want to invite Carol to the dance?” But at this moment, we don’t even know there’s a dance yet. And we don’t know that Emily knows Davis is looking for someone to ask to the dance. So it’s odd for her to say something in relation to information she doesn’t have yet. Something like, “That’s why I’m here? You want to ask Carol to the dance??” would’ve been clearer.

Despite this, the combination of the idea, the cleverness, and the charm made Lost Dog a real treat to read. My favorite short of the week!

Script link: Lost Dog

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Show-Don’t-Tell Alert – Instead of Mr. Spleen using character dialogue to tell us Davis and Emily have been friends forever, he has Davis toss a paper-airplane message to Emily’s house, where, after she’s done reading it, she throws in a box filled with a bunch of other paper airplanes from Davis. That’s one of the things I really loved about this script. Mr. Spleen always tried to show rather than tell. And if that wasn’t good enough, the image ALSO told us that Emily had a crush on Davis. Killing two birds with one stone on a “show-don’t-tell.” That’s good writing!