Get Your Script Reviewed On Scriptshadow!: To submit your script for an Amateur Review, send in a PDF of your script, along with the title, genre, logline, and finally, something interesting about yourself and/or your script that you’d like us to post along with the script if reviewed. Use my submission address please: Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Remember that your script will be posted. If you’re nervous about the effects of a bad review, feel free to use an alias name and/or title. It’s a good idea to resubmit every couple of weeks so your submission stays near the top.

Newsletter Update: There will be no newsletter this week, just a quick Christmas Gift e-mail that you’re going to want to open IMMEDIATELY. This is a special kind of gift, the kind that if you open late, there may not be anything inside. So be on the lookout tomorrow. I’ll be doing posts on Monday and Tuesday, but no major posts for the rest of Christmas Week. However, as I am wont to do, I may throw something up on a whim. If you’re not on the Newsletter, GET ON IT NOW. Here’s last week’s newsletter to see what you’re missing.

Genre: Action/Adventure

Premise (from writer): When contact with an expedition on the trail of a mythical treasure is mysteriously lost, a paratrooper, a gentleman thief, and an archeologist must join forces, or risk losing them forever to sinister forces bent on the same prize.

About: Okay, a little background on this one. We didn’t have an Amateur Offerings two weeks ago, which left today’s slot open. Now it just so happened that Mikko, the writer of today’s script, e-mailed as I was trying to decide what to review, and reminded me of his screenplay, which had the unfortunate duty of going up against “Where Angels Die” in a previous Amateur Offerings post. I looked back at the post, saw that some folks liked it, and said, sure, let’s go with this one. And this is why it never hurts to politely remind folks about your script. You never know when someone’s going to have a free moment to pop your script open. But they won’t do it if they’ve forgotten about it. Of course, don’t go overboard. Just a polite nudge every once in awhile will do the trick. – Note: This is an updated draft from 6 months ago. Mikko took many of the notes he received from that original post and applied them.

Why You Should Read (from writer): It received a 8/10 paid review on the Black List, but more importantly it was your post promoting the Tracking Board Launch Pad screenwriting competition that got me to enter that competition. I ended up making the Top 25 semis, but I didn’t make the cut to the Top 10. I was hoping you might give my script a go and share some insight into how to make it into a script that would’ve cracked the Top 10.

Writer: Mikko Tormala

Details: 119 pages

The Jaguar’s Fang was pitched as an adventure movie in the vein of Raiders of the Lost Ark. Now on the one hand, that’s exciting. We’ve been looking for the next Indiana Jones for 30 years now. On the other, it’s a bit of a death trap. By saying your script is like Raiders, you’re asking the reader to compare it to Raiders. And that’s what happened here. I was constantly comparing the two scripts. And how do you think you’re going to fare against the best action adventure movie of all time?

Exactly!

But that’s not to say The Jaguar’s Fang is bad. I totally see why this finished Top 25 in The Tracking Board contest. It’s a solidly written adventure film with plenty of GSU and a professional polish to it. But there is something missing here. Something that’s keeping it from reaching the next level. I’m not sure I know what it is yet. But as I talk through the reading experience, I’m sure I’ll figure it out.

The Jaguar’s Fang is set in 1945, and focuses on a World War 2 paratrooper, Quentin Riley, who lost his best friend in battle while defending a bridge from the Germans. It’s been a year and Riley’s taken to the drink. When he learns his friend’s father has disappeared on an expedition to the Yucatan, he vows to find him and give him a letter his son wrote him before he died.

Joining Quentin is sword-fighting thief George McAllister, who gives everything he steals to the needy, and Mary Bronstall, a stowaway whose father was also on the missing expedition. Mary was supposed to stay away but the gal’s too darn feisty to obey orders.

The Expedition was looking for an ancient relic known as the Jaguar’s Fang, which is not only worth millions itself, but is supposed to contain some sort of map that will lead to endless treasures. Of course, it just happens to be located amidst the never-ending jungles of the Yucatan where many an explorer has gone to never see the light of day again.

But our crew gets lucky. They find a lost city where the expedition last camped and follow their trail (spoiler) to an underground Mayan society that is still in existence! Ruled by a barbaric king, they will need to snag the expedition members TONIGHT before they are sacrificed and get the hell out of there or have this underground city become their underground tomb.

Okay, so like I said, there was a lot of good here. We have the goal of finding this lost expedition. There’s a nice mystery. Where did they disappear to? The motivations are all there (Riley needs to get this letter to his dead friend’s father. Mary needs to save her father). And some urgency starts to kick in when another group chases them.

All of that seemed textbook to me.

So then what was missing?

For me, something was lacking on the character front. Riley felt a little bland. He was certainly active, which is good. That’s how you want your hero to be. He was selfless (doing this for his friend), so he was likable. But he lacked definition as a character. I couldn’t peg what kind of person he was (Luke Skywalker, for example, can easily be pegged as a kid with big dreams who wants to take down the Empire). And he didn’t have any personality. He wasn’t funny. He wasn’t sly. He wasn’t unique or unpredictable or roguish or selfish. He was a normal guy trying to get something done.

This is one of the scariest things about screenwriting. You can get a whole hell of a lot right. But if we’re not on board with your main character, it won’t matter.

Similarly, I didn’t know what was going on with George McAllister. At times, I wasn’t sure if this was a two-hander (two protagonists) or if he was just a sidekick. Regardless, he was too soft. He starts off as this sword-fighting thief, but then quickly fades into the background, offering occasional humorous quips. Again, we have another character who’s lacking in definition and personality. If you want to create a Jack Sparrow character, McAllister’s gotta be WAY bigger on the page. If not, I’m not sure you even need this character. I struggled to figure out what he was doing in the story.

In addition to these problems, there wasn’t anything in the script that felt new or fresh. In fact, for 75% of the story, we’re moving along a rather mundane repetitive path. We’re in the forest, we discover something minor, we hear the bad guys are getting closer, we keep moving. The underground Mayan city was the one big “Haven’t seen this before” moment, but it was too little too late. By that point, I hadn’t seen anything fresh enough to keep me invested.

And the set pieces. I mean, when you’re competing against Raiders, you’re competing against the king of set-pieces. And until the big finale, which was admittedly good, all the set pieces were tame. I’m not saying it’s easy to come up with stuff we’ve never seen before, but you have to try. You have to take chances because we readers read every day. We see the same imaginations come up with the same scenarios over and over again. You have to throw out and rewrite a lot of stuff to find those rare ORIGINAL moments. But it’ll be worth it, because your script WILL stand out when you do.

But it all comes back to the characters. If I were Mikko, I’d do a major character overhaul here. Ask yourself, if I didn’t have this wild adventure to put my characters in, would they still be interesting? Would they still say or do things that an audience would want to hear/see? Right now, the answer is no.

I was just reading the Marshal of Revelation (Wednesday’s review) and THAT script is character. Those are memorable people. I think part of the problem here is that everyone in this script is so squeaky clean. They’re so nice and cuddly. Even our thief doesn’t keep his money. He gives it to orphanages! Between Riley and McAllister, I would look to make one of these two a lot more edgy. By doing so, you’ll not only have a more interesting character, but you’ll have more conflict between your main characters (as they’ll want to solve problems in different ways), which should provide some more entertaining scenes.

Structurally, The Jaguar’s Fang is great. But until the character issues are solved, it’s going to be stuck just below “worth the read” level.

Script link: The Jaguar’s Fang

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: I think this genre of movie needs a protagonist with more edge. This isn’t It’s A Wonderful Life. It’s is a down-and-dirty adventure film. The hero needs a darkness to him, something that manifests itself negatively. Whether he’s self-destructive, manipulative, a womanizer. Something that gives his character SOME PERSONALITY. I think Mikko tried to do this with Riley’s drinking, but it became a non-factor as soon as they went on the journey, so it never felt like a true character vice.

Genre: Drama/Family/Fantasy

Premise: An ambitious man watches his life pass him by while sacrificing his dreams to help others. Feeling like a failure later in life, he tries to commit suicide, only to have an angel show him what the world would’ve been like had he never existed.

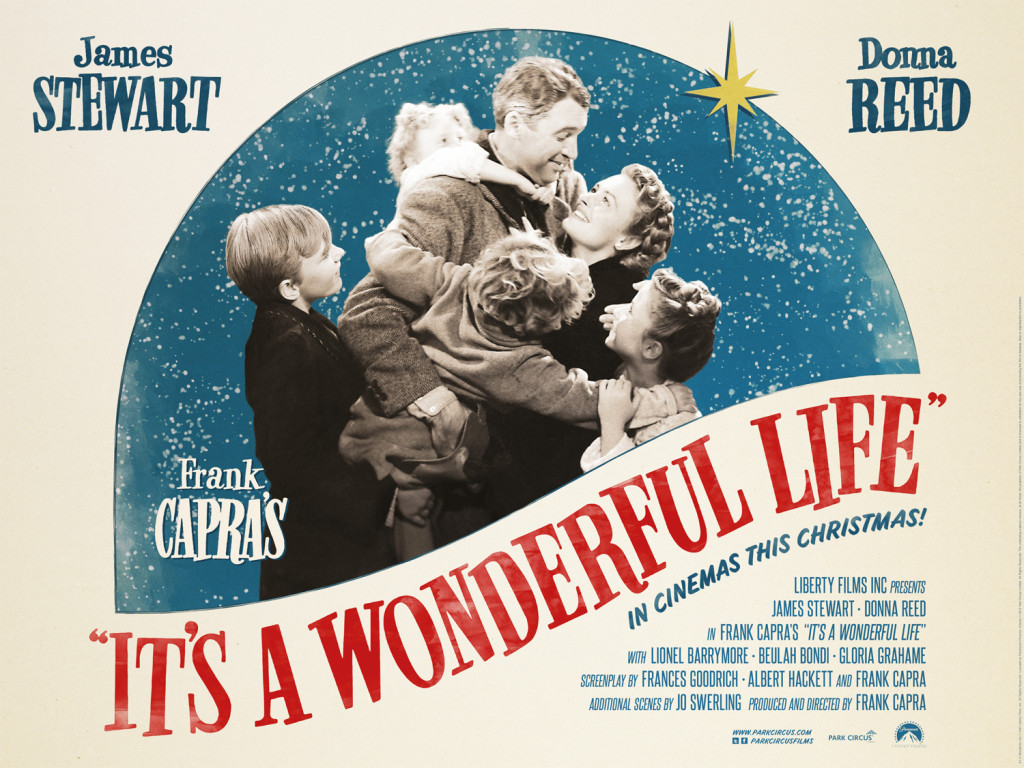

About: Directed by the great Frank Capra and starring the amazing James Stewart, It’s A Wonderful Life had quite the interesting life of its own. The film didn’t do well initially at the box office, but later became a staple on television networks leading up to Christmas, where audiences eventually fell in love with it. Director (and co-writer) Frank Capra had a fascinating career as a director. He won 3 (count’em THREE) Oscars as a director in the 30s. However, after World War 2, his optimistic endearing films didn’t play to a world whose mood had turned cynical. In fact, “It’s A Wonderful Life” was considered by many critics (at the time) to be the film that signified Capra was no longer in touch with the public. Amazingly, Capra made his last movie nearly 30 years before he died, a rarity for directors.

Writer: Frances Goodrich, Albert Hackett, Frank Capra, Jo Swerling, Philip Van Doren Stern and Michael Wilson

Details: 130 minutes

Gotta admit, this one always gets me. Things get a little emotional at the Scriptshadow compound when the end of It’s A Wonderful Life plays. I mean, I’m not confirming any tears here. The so-called “visual evidence” of drenched tissues reported on some websites is completely fabricated and/or tampered with. But as each year passes, and Christmas seems less like a magical experience and more like a government-driven holiday to make us open our wallets, Frank Capra and James Stewart remind me just how sweet and nice the holiday can be.

Yeah yeah, emotions and all that. This is still a screenwriting site, so when I popped “Life” in this year, I still needed an angle to explore the film from. It came to me rather quickly. I realized I wanted to know what made a story timeless. What makes something worthy of coming back to year after year? Because, as you know, the majority of movies we watch leave our brains by the time we’re back in the parking lot. If we could discover even a piece of what makes a screenplay timeless, we could all become better writers.

For those who haven’t seen It’s A Wonderful Life, it’s set during the 20s, 30s and 40s, and centers around an idealistic dreamer named George Bailey. George lives in a tiny town called Bedford Falls that he can’t wait to leave. If there’s a country George isn’t planning on travelling to, it isn’t on the map yet. And so when he hits his 20s, he readies himself for that life of adventure.

But then his father dies, who happened to be the president of the family business, an old Building and Loan that is the only respite the town has from the evil Mr. Potter, a dastardly old weasel who holds the town hostage with crippling loan terms that leave him rich and everyone else desperate. Since the Building and Loan is the only thing standing in the way of him controlling the town completely, Mr. Potter will stop at nothing to take it down.

In order to keep the town out of Potter’s hands, George is forced to take his dad’s place, and thus begins a series of events over the years where the timing is never right for George to get away. Soon he’s married with five children, barely getting by, wondering what his life would’ve been like had he followed his dreams instead of helping others. On the night he plans to commit suicide, an angel appears and gives him a spectacular gift: He shows him what the world would’ve been like if George Bailey had never lived.

Watching It’s A Wonderful Life this time around, it didn’t take long to realize why it’s the gift that keeps on giving. It’s all about universal timeless themes, things that man had to deal with a thousand years ago and things that man will still be dealing with a thousand years from now.

Helping others versus helping yourself is the main theme that plays throughout “Life.” There’s also the theme of sacrifice. There’s the theme of the underdog. There’s the theme of struggle – trying to make it through each day, despite the countless obstacles we face. We have a villain who stands for corruption and greed, something every town, city, and country experiences on some level. We have the power of love. We have the importance of family. These are things that every human being knows. Contrast that with, say, Green Lantern. What, if any, part of that movie connects with audiences on a deeper level? What timeless themes does it explore? Of course, just covering these bases isn’t enough. You still have to do it in an entertaining way. You still have to construct a story that’s dramatically compelling. And Capra and his 200 screenwriters achieve that in spades.

One of the biggest reasons It’s A Wonderful Life works is because you freaking LOVE the main character. I mean, could you design a persona more lovable than George Bailey? The man is the ultimate selfless human being. He sacrifices all his dreams to keep the Building and Loan from folding. He sacrifices them again so his brother can go to college. He gives his OWN money to people if the money from the bank isn’t enough. As a kid, he sticks up to the villain, Mr. Potter (heroes who aren’t afraid of villains are always likable)! Even in death, George Bailey is still giving. When he decides to commit suicide, it isn’t out of selfishness. It’s because he knows he’s worth more dead than alive, and that the money his family will get from his life insurance policy will allow them to survive.

It is through all this giving that I began to notice something. These days, screenwriters only make their characters “good” at the beginning of their script, in the form of a “save the cat” moment, designed to make you “like” them. The problem is, the audience has become keen to this device and aren’t as easily tricked. They know when you’re conning them, and therefore a save the cat moment can actually backfire. The reason George Bailey is so damn likable is because his acts of kindness never end! They happen again and again and again. That consistency makes us trust him, makes us believe he’s a good guy. And that’s why we like him so much.

Capra also understood that a great hero is nothing without a great villain. We need someone to root against just as much as we need someone to root for. Mr. Potter is almost as memorable as George Bailey, and I think it’s because of one clever choice. Putting Potter in a wheelchair. Making Potter a “cripple” distracted us from the fact that Potter is essentially a caricature. He is mean just to be mean. But dammit if that wheelchair doesn’t distract us from this truth. Villains aren’t supposed to be in wheelchairs, we say. And so, like a magician’s misdirect, it makes us think that Mr. Potter is indeed, a real person.

Capra is also wise enough to know that if a bad thing is going to happen to our hero, the villain must always be a part of it. What good is having a villain if they aren’t orchestrating your hero’s downfall! So there’s a key scene late where Uncle Billy, George’s bumbling second-in-command, misplaces 8000 dollars, which will ultimately lead George into the tailspin that results in his attempted suicide. I mean sure, you could’ve stopped there. That was enough to get the story where it needed to go. But Capra took that one extra step and made Potter realize Uncle Billy’s mistake, and snatch the erroneously placed money when he wasn’t looking.

Then of course, there’s the ending, where everyone comes to George’s house and gives him money to bail him out. You know this moment because you’ve seen it in dozens of movies. However, this is the ONLY FILM IN HISTORY where it’s actually worked. Why? Because, of course, it’s SET UP. Actually, it’s born out of a thousand set-ups. We’ve seen, over the past two hours, as George has personally helped all of these people. So the fact that they would help him back in his time of need goes unquestioned. Nobody who’s ever used this copycat ending seems to realize this, which is why every subsequent attempt has been a disaster.

It’s A Wonderful Life is about characters. It’s about struggle. It’s about holding true to your values. And it’s about good versus evil. What’s more universal than that??

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[x] genius

What I learned: Have your hero KEEP being good instead of just giving him a contrived “save the cat” scene early on. This consistency will lead to an authenticity in your character, which will result in us trusting and rooting for him.

Genre: Western

Premise: The story of a slimy town marshal who saved the town of Revelation, Wyoming with the help of a mysterious Jewish gunman.

About: Jon Favreau (director of Iron Man) wrote this script while editing the film he’s still probably best known for, Swingers. He and Vince Vaughn really wanted to make it but could never find financing. It’s considered a relic of the past. But maybe Favreau wasn’t right to give up on it. Maybe, just maybe, this is his best script.

Writer: Jon Favreau

Details: 115 – pages (12/17/96) draft

I FINALLY understand why Favreau directed Cowboys & Aliens! I didn’t know why anybody would want to make that film. But it’s obvious now he regretted never being able to make “Marshal of Revelation,” and realized this would be his only shot to make a Western.

So what’s going on with this mysterious script you’ve probably never heard of? A script that had no business being good (I mean seriously, are there more boring words to open a screenplay to than “Wyoming, 1877?”). Well after those words disappear, we endure a horrifying scene where a gang of mixed nationalities swoop in on a family home, kill a father, brutally rape and murder the wife, and then wait hours for the hiding son so that when he emerges to run away, they can murder him too. Hmm, maybe Wyoming 1877 isn’t so boring after all.

Jump forward a couple of years and we meet Isaac Meek, the 1880 equivalent of a car salesman. He’s rough around the edges. But he’s handsome enough and he’s got the gift of gab, which allows him to bed many ladies and talk his way out of any situation. That is until he bangs a business associate’s wife. A Chicago bigwig. Isaac realizes that his life is now in danger so he does what he does best – runs.

He eventually bumps into a Jewish cowboy searching for a Russian man. The Russian man turns out to be the same leader of that gang who massacred the family in the first scene. Apparently, he’s been doing this to many families, and started with the Jew’s. So the Jew’s out for a little revenge. And much like Inigo Montoya, he’s been training his ENTIRE LIFE for this meet-up. As a result, he’s the BEST shot in the country (even better than Buffalo Bill – who makes an appearance later!).

Sensing he needs protection, Isaac promises to help the Jew find the Russian if he becomes Isaac’s bodyguard. The two soon find themselves strolling into the town of Revelation, a once thriving city that’s since been overrun by criminals. After a dazzling display of gunmanship and a few dead bad guys (all done by the Jew but orchestrated by Isaac), the town begins to rally around Isaac as a savior, and makes him the Marshal.

As they continue to clean up the town, Isaac’s legend grows, with no one realizing that it’s the Jew who’s doing all the killing here. However, when the Jew realizes Isaac’s been lying and hasn’t done a thing to find the Russian, he leaves. Finally, Isaac will have to prove his worth on his own, a challenging proposition since he’s grown so fond of his legend that he no longer knows what’s real and what’s fable.

Favreau wanted Vaughn to star. Would he have played Isaac?

Favreau wanted Vaughn to star. Would he have played Isaac?

Damn, this script was good! It feels Django-like, albeit reigned in. I wouldn’t even be surprised if Quentin read this back in the day and was inspired by it. The Jew very much feels like Django (discriminated against, stoic and quiet) while Isaac is the more flamboyant personality-infused of the two.

Speaking of personality, this script taught me a lot about it. I NEED personality in at least ONE of my major characters. I’ve brought this up quite a bit lately because I continue to read a ton of material with forgettable characters.

We focus so much on things like flaws and backstory and character actions, we forget those only do so much. If a person doesn’t talk in some sort of interesting way, they usually lack personality, which makes them boring. Han Solo, Hannibal Lecter, Lloyd Dobler, Juno, Jack Sparrow, Tony Stark. Give me someone who lights up the page!

Well, you can now add Isaac Meeks to that list. Isaac is a salesman. He’s a con man. He’s a selfish swindler. He can talk himself out of ANYTHING and while we may hate the guy, we sure enjoy watching him work. For example, early on in a whorehouse, Isaac’s confronted by two men. Rather than fight, he plots a more… “Isaac-like” solution:

ISAAC

I can see where this is headed. As you can see, not only is it two on one, but I am without my pistol. Now, if you don’t share General Lee’s yellow streak, you’ll wait for a moment while I go to my room and fetch my revolver.

SOME GUY

Here, Meek, use mine…

ISAAC

I’m afraid that won’t do. A gunfighter’s tools are as unique as his personality…

WHORE

I’ll fetch it…

ISAAC

I’m afraid that won’t do. A gunfighter organizes his belongings in a way as unique as…

SAM

(fed up with the stalling)

Fetch your iron!

Of course, Isaac pretends to do just that, but when the gunmen rush to his room, all they see is an open window and a pair of blowing curtains.

But here’s the reason I really liked “Marshall.” Favreau not only created a great character who oozes personality, he created a great character with zero personality – the Jew. The Jew was all about action. He was all about looks. Where as Isaac sought the spotlight, the Jew basked in the shadows.

Characters like these (quiet ones) are tough to write because the lack of dialogue dims their light on the page. They don’t pop as much. But because the Jew was SO DAMN GOOD at his job and so driven (he’d stop at nothing to kill the Russian), we enjoyed him just as much as we did Isaac.

This script used a lot of Scriptshadow principles as well. The character goals were clear and strong (clean up the town, kill the Russian). The motivation was high (the Russian killed The Jew’s family). We had two very interesting main characters that actors would want to play. And due to the stark contrast in personality of our leads, there was tons of conflict. One couldn’t shut up. The other never said a thing. One was a coward. The other was brave. One had principles. The other stood for nothing. When you have a two-hander like this, you’re really writing THREE characters. You’re writing Character A. You’re writing Character B. And then you’re writing THE DYNAMIC BETWEEN CHARACTER A AND CHARACTER B. If you haven’t given thought to that third character, your two-hander’s probably missing something.

The failure of this film to get made probably comes down to trying to find financing for one of the least bankable genres in Hollywood. You saw what happened with Cowboys & Aliens. You saw what happened with The Lone Ranger. To get these made, you probably need a top ten director on board, who will pull with him a couple of major stars. So it’s too bad that The Lone Ranger tanked. It means a resurgence for The Marshal of Revelation is unlikely. Still, this is a really good script. Nice job, Jon!

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: In my book, I talk about the advantage of using “scene agitators” in your scenes. This refers to a third element that occurs outside the primary action/dialogue that gives the scene a little more kick. You use them because oftentimes, having only two people interacting is boring. So in “Marshal,” there’s this great scene where Isaac is playing poker against some dangerous locals. The pot has gotten huge, and the leader believes Isaac is cheating them. As Isaac and the leader keep raising the pot, a man walks in the bar (who we’ll later find out is the Jew). The leader, who doesn’t like Jews, tells him to leave. The Jew ignores him, sits down, and orders a drink. The leader continues to raise the pot, but is agitated by the fact that the Jew is ignoring him. So between exchanges with Isaac, he keeps turning to the Jew and telling him to leave. The pot increases and the tension with the Jew increases until finally the leader storms over and confronts the Jew. This is exactly how you want to use a scene agitator. The poker scene by itself was good. But the agitation the Jew adds makes it great.

The Black List is here! I wish I could write some big fancy opening but I’m busy looking at multi-million dollar houses in the hills I’m going to buy once I win the California Mega-Lottery tonight. So here are the script loglines and my thoughts on each! What do you guys think? Too much cancer?

46

HOLLAND, MICHIGAN

by Andrew Sodroski

Logline: When a traditional Midwestern woman suspects her husband of infidelity, an amateur investigation unravels.

Thoughts: This script is being directed by Errol Morris. This is his first feature. He’s done a bunch of documentaries and is quite simply one of the best documentarians around. If you haven’t seen his old doc, The Thin Blue Line, go rent it. It’s an artistic approach to what’s traditionally a very nuts & bolts style of filmmaking. As for Andrew Sodroski, I can’t say I’ve ever heard of him before. I believe this is his breakthrough screenplay. Good job, Andrew!

44

SECTION 6 by

Aaron Berg

Logline: An exploration of the formation of Great Britain’s secret intelligence agency, Military Intelligence, Section 6, known as MI6.

Thoughts: The big spec sale of the year. I’ve read the first 15 pages of this script and found it to be very thick and hard to get through. Admittedly, it’s not my type of material, so I decided not to read the rest. The producers went on a campaign to get this script out of the public by getting all script links erased across the web. Which I think backfired. The harder something is to find, the more people want it, so the more people were trading it. So it’s definitely out there. Personally, I think this is a concept sell. Someone really really wanted to make a movie about the formation of MI6. Not a bad idea. Spy scripts sell!

39

FRISCO

by Simon Stephenson

Logline: A forty-something pediatric allergist, who specializes in hazelnut and is facing a divorce, learns lessons in living from a wise-beyond-her-years terminally ill 15-year-old patient when she crashes his weekend trip to a conference in San Francisco.

Thoughts: I love the description of the main character (pediatric allergist). Never seen that character before in a script. But the “wise-beyond-her-years” terminally ill 15 year old?? Nooooooo. I see so many of these. That being said, these scripts are so execution-dependent that it could go either way.

27

A MONSTER CALLS

by Patrick Ness

Logline: An adolescent boy with a terminally ill single mother begins having visions of a tree monster, who tells him the truths about life in the form of three stories, helping him to eventually cope with his emotions over his dying mom.

Thoughts: Ahhh, another dying person. Gotta admit, I’m not a huge fan of “dying people” scripts. There’s this overarching tone of depression that makes the read a slog, even if it’s “good.” But this sounds inventive and a little different at least. Ness is a novelist whose book series “Chaos Walking,” is in development to become a film.

25

THE SPECIAL PROGRAM

by Debora Cahn

Logline:

The true story of Jack Goldsmith, a young attorney who took charge of the White House’s Office of Legal Counsel, then courageously took on Vice President Cheney and his powerful inner circle when he discovered they were running a number of illegal activities through their so-called “Special Program”.

Thoughts: I’m still convinced that the main execs The Black List sends its voting list to work at a production company that operates out of the White House because there’s always one or two of these political scripts in the top 5, then you never hear from them again (seriously, who goes to watch political movies?). Let’s hope Debora’s script breaks that yucky streak.

24

HOT SUMMER NIGHTS

by Elijah Bynum

Logline: A teenager’s life spirals out of control when he befriends the town’s rebel, falls in love, and gets entangled in selling drugs over one summer in Cape Cod.

Thoughts: These coming-of-age scripts all depend on voice. Because they’re so common, you have to differentiate yourself somehow. And when you think about it, this is the ideal genre to exhibit your voice, since coming-of-age movies are almost always autobiographical. Elijah looks like a first timer so he could very well be the new voice a script like this needs.

SOVEREIGN

by Geoff Tock and Greg Weidman

Logline: A man goes to space to destroy the ship that, upon going sentient, killed his wife.

Thoughts: Well it’s a highly ranked science fiction script on the Black List so, duh, I’m going to read it, but this logline doesn’t tell us much. I don’t know what a ship going sentient means. I think these two wrote an episode of NCIS: Los Angeles together, but it may have only been Weidman. Either way, another set of newcomers, which there seem to be a lot of on this list. Which is great!

22

SHOVEL BUDDIES

by Jason Mark Hellerman

Logline: Over 24 hours, four teenage friends try to complete the “Shovel List” (a will/bucket list) left for them by their best friend before he died of Leukemia.

Thoughts: More cancer! More dying! Actually, at least this cancer dude’s already dead. I like the idea of shifting the “Bucket List” idea to kids. And I like the tight time frame (implies the story’s going to move – very spec-friendly). But it’s hard to sell death to audiences. Nobody likes to be depressed!

20

POX AMERICANA

by Frank John Hughes

Logline: In the Old West, a group of soldiers go on a mission to slaughter a peaceful tribe in retaliation for another tribe’s attack on a white settlement, only to suffer at the hands of a devastating disease.

Thoughts: Mmmm, suffering at the hands of a disease. That sounds uplifting. Takes a good writer to keep that slow build of a Western interesting enough to keep the Twitter-raised reader of today interested. Frank John Hughes is actually an actor who’s been in a TON of stuff (including Catch Me If You Can and Bad Boys).

REMINISCENCE

by Lisa Joy Nolan

Logline: An “archeologist” whose technology allows you to relive your past finds himself abusing his own science to find the missing love of his life.

Thoughts: This was a huge sale that was read by everybody (which is probably why it made the list – pure numbers) but probably the more interesting story is that it was written by Jonathan Nolan’s wife, who will always be dogged by the assumption that it was sold due to nepotism. I haven’t read the script myself yet but the few people I’ve talked to who have didn’t have very nice things to say about it. With that said, kudos to her for sending it out without the “Nolan” name on it.

THE INDEPENDENT

by Evan Parter

Logline: With America’s first viable independent Presidential Candidate poised for victory, an idealistic young journalist uncovers a conspiracy, which places the fate of the election, and the country, in his hands.

Thoughts: Okay okay. This sounds a little different. I like the idea of an independent president winning the election (something we probably need). That’s all I ask. If you’re going to write about something we’ve seen before, find a new angle. That earlier political logline felt “been there done that.” This feels fresh and new.

19

BEAST

by Zach Dean

Logline: With the hope of starting over, a reformed criminal with an ultra-violent past returns home, but when he finds his own family leading his teenaged son down the same path of destruction, he will stop at nothing to save his child.

Thoughts: Don’t know much about Zach Dean but he seems to like these gritty crime pieces. His lone credit, Deadfall (starring Eric Bana and Olivia Wilde) is a gritty film about a casino heist. Again, the less high concept your idea is, the more execution-dependent it becomes. So we’ll only know if this thing’s any good when we read it.

THE GOLDEN RECORD

by Aaron and Jordan Kandell

Logline: The true story of how Carl Sagan fell in love while leading the wildest mission in NASA history: a golden record to encapsulate the experience of life on earth for advanced extraterrestrial life.

Thoughts: I am an unabashed fan of Contact, and I’ve always been intrigued by this idea of humanity creating a gold record to explain who we are to others. This could be schmaltzy and melodramatic if done wrong, but I’d be lying if I said I didn’t want to read it. Could be awesome if this sibling writing team pulls it off.

18

FAULTS

by Riley Stearns

Logline: An expert on cults is hired by a mother and father to kidnap and deprogram their brainwashed daughter. He soon begins to suspect the parents may be more destructive than the cult he’s been hired to save her from.

Thoughts: I love this idea! I love cults. They’re fucking freaky! And I always love when a script turns and doesn’t do the obvious thing (the parents being worse than the cult). Will be reading this one for sure!

SWEETHEART

by Jack Stanley

Logline: A young hitwoman tries to escape the business but finds herself in more danger after a high school reunion and a one-night stand.

Thoughts: It drives me nuts they don’t provide genres for these. I’m guessing this is a comedy, which would make it a re-imagining of Grosse Pointe Black, with a female lead? That is an easy way to get noticed. Take a movie that worked before and change the gender of the main character. Go ahead, try it!

17

SUPERBRAT by

Eric Slovin and Leo Allen

Logline: Temperamental tennis champion John McEnroe is sucked into a dangerous and ludicrous law enforcement sting during Wimbledon in 1980.

Thoughts: When I was a kid, tennis was my life. I’ve been dying for someone to write a good tennis script ever since I got to LA. That time may finally have come. And I love how it’s not an obvious premise. It sounds bizarre and very un-tennis-like, which is an advantage because I think tennis is boring to the lay-person. YOU CANNOT BE SERIOUS! I am all over this.

16

DOGFIGHT

by Nicole Riegel

Logline: A 15-year-old boy discovers that his kidnapped older brother has been living in a hidden, meth-producing compound, and infiltrates the camp in hopes of helping his brother escape.

Thoughts: Yeah baby. Breaking Bad meets high school! And yet another new voice! Haven’t heard of Nicole before.

THE CIVILIAN

by Rachel Long and Brian Pittman

Logline: After an American doctor has his identity stolen by a covert operative, he must assume the dangerous mission of the one who stole it in order to clear his name.

Thoughts: Gotta admit, this one sounds a little “been there done that.” Hope it’s got some juicy offbeat choices inside. Probably won’t seek this out unless someone I know tells me it’s good. These two wrote a movie for director Rob Cohen called 1950 about an American in Korea that was supposed to be the biggest movie ever shot in Korea. That was in 2011 though and I don’t know where the project stands.

15

BURN SITE

by Doug Simon

Logline:

After a young teenage girl is murdered, her stepfather falls back on his dark and violent past to find her killer.

Thoughts: Okay, a little revenge title here. Sounds a bit generic but maybe they’re holding back the details. Remember that it isn’t the writers writing these loglines for the Black List (how could they? They don’t even know they’re on the list until it comes out). The agents or managers are often asked for loglines ahead of time, and they might not be so great at writing them.

QUEEN OF HEARTS

by Stephanie Shannon

Logline: Inspired by true events, this is the story of “Alice in Wonderland” and “Through the Looking Glass” author Lewis Carroll (aka Charles L. Dodgson) and how his relationship with the real Alice Liddell and her family may have inspired one of the world’s most beloved pieces of children’s literature.

Thoughts: While typically not my thing, these scripts play like gangbusters on the Black List. Write about a famous author growing up and producers gravitate to your script like bees to honey. The Muppet Man, Seuss, A Boy And His Tiger (below). This may be the secret sauce that guarantees a Black List spot! Oh, Stephanie Shannon also won the Nicholl Fellowship with this script.

14

BROKEN COVE

by Declan O’Dwyer

Logline: After his brother is found brutally murdered, a man hellbent on revenge returns to his decrepit Irish fishing village home armed only with a mysterious list of names his brother left behind.

Thoughts: Another revenge movie! Although this one sounds a lot less generic. The setting feels different, and the “list of names” adds a mystery box element to the idea. Great news for those of you living outside the states. Declan doesn’t live in the U.S! (see, it can be done).

GAY KID AND FAT CHICK

by Bo Burnham

Logline: Two high school misfits become costumed vigilantes and take out their frustrations on the students who have bullied them throughout high school.

Thoughts: Uhhhh, this is easily the best title on the list (assuming you have a sense of humor). It’s a great reminder that you have to force someone to want to pick up your script amongst the others in the pile. Coming up with a clever or controversial title is an easy way to do that.

13

1969: A SPACE ODYSSEY OR HOW KUBRICK LEARNED TO STOP WORRYING AND LAND ON THE MOON

by Stephany Folsom

Logline: With NASA’s Apollo program in trouble and the Soviets threatening nuclear war, a female PR operative conspires with NASA’s Public Affairs Office to stage a fake moon landing in case Armstrong and Aldren fail, the goal being to generate public excitement that will aid the U.S. in winning the Cold War. But the op is faced with the biggest challenge of all: Filming the fake lunar landing with temperamental Stanley Kubrick.

Thoughts: This sounds like it could be awesome. At least for nerds. Imagine how much fun you could have with Stanley Kubrick as one of your characters. This is obviously playing off the surprise success of Argo. And this one sounds like it could be more fun. Folsom is another new writer on the scene. She’s got a tiny TV show to her name (Ds2dio 360) but that’s it.

AUTOPSY OF JANE DOE

by Richard Naing and Ian Goldberg

Logline: A father/son mortician team try to uncover the cause of death on a Jane Doe. The more they uncover, the more mysterious and terrifying their world becomes.

Thoughts: Okay, so obviously they don’t want to give too much away here. This could be a thriller or a straight-up horror. Hard to tell. But it sounds good. Making ends meet, co-writer Richard Naing produces the reality show “Behind The Mask” about the people behind sports mascots.

THE MAYOR OF SHARK CITY

by Nick Creature and Michael Sweeney

Logline: When a difficult film shoot spirals hopelessly out of control into a living nightmare, an ambitious young director must face his greatest fears to turn a troubled production into the biggest movie of all time. Set on Martha’s Vineyard during the summer of 1974, this is the untold story of the making of Jaws.

Thoughts: One of two scripts about the making of Jaws. I know Grendl is going to be all over this!

WHERE ANGELS DIE

by Alexander Felix

Logline: A street-tough, white social worker in the slums of Detroit acts on a dangerous and violent personal vendetta when he protects a young girl and her mother from her recently incarcerated, AIDS-infected boyfriend, after he abruptly massacres a seedy strip club in a rage.

Thoughts: For those unaware, we discovered Mr. Felix right here on Scriptshadow on an Amateur Friday review! I LOVED it and put it in my Top 10. Alex went on to be managed by Energy, got agents at CAA. He got over 60 general meetings from the script and is up for some big assignments around town. Alex and I have been meeting every week or so and he’s keeping me up to date on what he can. The script was primed to be made before, but now that it’s on the Black List, I’m predicting really good things. Congrats Alex Felix!

A BEAUTIFUL DAY IN THE NEIGHBORHOOD

by Alexis C. Jolly

Logline: Set in 1950s Manhattan, Fred Rogers journeys from a naive young man working for NBC to the host of the beloved children’s TV show, Mr Rogers’ Neighborhood.

Thoughts: Another biopic. Another no thank you. Another WAIT, I TAKE THAT BACK! Mr. Rogers’ Neighborhood?? I’m in! However, these scripts only tend to work if the real life persona is the exact opposite of the TV persona. I’m not getting that sense here so I guess it’ll come down to if Fred Rogers led an interesting life. And who better to write Mr. Rogers than someone named “Jolly!”

INK AND BONE

by Zak Olkewicz

Logline: When a female book editor visits the home of a horror writer so he can complete his novel, she finds that all of his creations are holding him hostage.

Thoughts: I reviewed this on my newsletter awhile back. I think it’s a strong marketable idea – very Stephen King’ish – but the execution needs some work. It was too muddied in the middle. But I’ll props to Zak, some of the creatures were terrifying.

11

THE BOY AND HIS TIGER

by Dan Dollar

Logline: The true story of Bill Watterson, the creator of Calvin & Hobbes.

Thoughts: “Dan Dollar?” you might be saying. “I recognize that name.” Yeah, Dan’s contributed plenty of times to the Comments Section of Scriptshadow. A big congratulations to him. Another reminder that with hard work and great writing, you can make it. Dan’s proof that it happens.

THE KILLING FLOOR

by Bac Delorme and Stephen Clarke

Logline: A war veteran slaughterhouse worker and his friend discover a small fortune in heroin hidden inside a processed cow and maneuver to hold onto their find and cash out to save his grandfather’s house as the bad guys come looking for their wayward stash.

Thoughts: Whoa! This logline’s a mouthful. Co-writer Bac Delorme is a longtime assistant director. You’re probably seen a ton of his movies. While the logline’s thrown me for a loop, I trust this one because it’s repped by David Karp at WME, who’s got some of the best taste in town.

10

I’M PROUD OF YOU

by Noah Harpster and Micah Fitzerman Blue

Logline:

Based on Tim Madigan’s autobiographical novel of the same name. A journalist looking for a story about television’s role in the Columbine tragedy interviews TV’s Mr Rogers and, as a friendship develops between the two, he finds himself confronting his own issues at home.

Thoughts: This is just too weird. Two Mr. Rogers scripts in the same Black List? This is why I’m never surprised when someone comes to me with the same obscure logline as someone else. There’s something in the air with people. We’re all feeding off the same media cycle. We’re programmed to think alike. Which explains how there’s never been a Mr. Rogers script in history and then this year there’s 2 big ones.

SEED

by Christina Hodson

Logline: After suffering a devastating miscarriage, a young woman and her fiance travel to Italy where she meets his family for the first time, but her grief turns to shock when the local doctor declares that she’s still pregnant. And while her fiance and his family seem delighted by the news, she begins to suspect their true motives are quiet sinister.

Thoughts: I really liked Hodson’s entry on last year’s Black List, Shut In, about A woman who takes care of her comatose teenaged son at home then starts getting visits from the ghost of a runaway boy. It totally kept you guessing. So I can only imagine this one’s going to be just as good.

THE COMPANY MAN

by Andrew Cypiot

Logline: Based on true events. CIA agent Edwin Wilson went behind enemy lines to secure weapons contracts and report information back to the CIA shortly after the Cold War. He had a meteoric rise until company policies changed and he was unceremoniously fired, but he continued to operate as a man without a country and became public enemy number one in the U.S. Attorney’s office.

Thoughts: Hmm, isn’t this the same thing as the NBC show “The Black List (ironically enough)?” I guess it’s based on a true story though. And people love spies! Why don’t I like spies? They’re inherently cool but I can’t seem to get into them. What’s crazy about this entry is that Cypiot only has one credit to his name, and it’s from 15 years ago on a TV movie! Way to stick with it, Andrew!

THE SHARK IS NOT WORKING

by Richard Cordiner

Logline: When his big break finally arrives, an idealistic young movie director, Steven Spielberg, risks failing to complete the movie Jaws when his 25-foot mechanical shark stops working.

Thoughts: Richard is a very talented writer who I actually gave notes to on this script a year ago. He’s got another cool script as well that producers should ask him about (which I don’t think I’m allowed to mention). I remember when I read this, Richard told me “This is my passion project.” And you could tell. That passion was on the page. Congrats, Richard!

9

THE CROWN

by Max Hurwitz

Logline: In exchange for a lighter prison sentence, a young hacker goes undercover for the FBI in a sting operation to find and steal a super computer virus with the help of a team of unsuspecting hackers.

Thoughts: Max is another young writer/director who’s worked on some small TV shows. There isn’t too much to go on with this logline (it sounds a mite familiar) but I’ll be the first to congratulate him if it turns out great.

DIABLO RUN

by Shea and Evan Mirzai

Logline: While on a road trip to Mexico, two best friends are forced to enter a thousand-mile death race with no rules.

Thoughts: I love this concept! Death Race meets Cannonball Run. This could be awesome.

RANDLE IS BENIGN

by Damien Ober

Logline: Follows a woman in the ’80s who works at an IBM-like company and is at the forefront of national intelligence research. When her project (named RANDLE) hits a major milestone indicating that she may have actually achieved AI, it is unexpectedly hijacked by the agenda of the company’s mysterious CEO. As she dives deeper into the corporate agenda, she learns that there may be a connection between her project and the 1981 assassination attempt on Ronald Reagan.

Thoughts: I thought for a second I’d stumbled on to the script itself! Big logline! This is a tough one. I kind of like it but there’s something “light” about inspecting an almost-assassination. Unless we get the tragedy of the assassination itself (JFK), do we really care?

TCHAIKOVSKY’S REQUIEM

by Jonathan Stokes

Logline: A conductor investigates the great composer’s seemingly unnatural death and unlocks the mysteries of the man himself while preparing to debut Tchaikovsky’s final symphony.

Thoughts: Stokes has been working hard, writing small feature films here and there. But nothing had that break-out appeal. This is a strong concept though. It’s got weight.

8

LINE OF DUTY

by Cory Miller

Logline: Macbeth meets The Departed in the modern retelling of Shakespeare’s play, focusing on the tragic rise and fall of NYPD officer Sean Stewart, a heroic narcotics detective pushed to the dark side of police corruption by his scheming wife and a well-timed prophecy.

Thoughts: Cory Miller was a former investigator on the NYPD Internal Affairs unit, so you know he’s going to bring some authenticity to this. He graduated from UCLA with a degree in writing and directing.

INQUEST

by Josh Simon

Logline: After the death of Princess Diana, a reluctant investigator is hired to ascertain whether her death was premeditated. And in the process, he begins to uncover a conspiracy that compromises his own safely.

Thoughts: This was a really big sale earlier in the year. I read the script though and was kind of disappointed. It’s really sad. It’s basically about this father (of Princess Diana’s boyfriend, also killed in the crash) who can’t let go of the fact that his son died in an accident, so he has to create a conspiracy in order to cope. Not bad but it’s not what you expect.

CAPSULE

by Ian Shorr

Logline: A young man’s life is turned upside down when he mysteriously begins to receive metallic capsules containing messages from his future self.

Thoughts: A bit familiar but this idea can work when done well. Ian Shorr made the Black List last year too!

FULLY WRECKED

by Jake Morse and Scott Wolman

Logline: An R-rated talking car from the ’80s is brought back into service and teamed up with the son of his former partner, a befuddled cop looking to earn his stripes.

Management: Kaplan/Perrone

Manager: Josh Goldenberg

Producer: Hurwitz & Schlossberg Productions

Thoughts: This sounds really funny. Knight Rider meets Beverly Hills Cop?

SPOTLIGHT

by Josh Singer and Tom McCarthy

Logline: The true-life account of the Boston Globe’s breaking of the Catholic priest scandal in 2003.

Thoughts: Gotta say, this sounds a little bit snore-worthy. Isn’t the Catholic priest thing old news by now?

EXTINCTION

by Spenser Cohen

Logline: A man must do everything he can to save his family from an alien invasion.

Thoughts: This comes from the young writing-producing team of Spenser Cohen (who also directs) and Anna Halberg. These two are a couple of the smartest up-and-comers I’ve met in town. Mark my words. At some point they’ll have the next Bad Robot!

REVELATION

by Hernany Perla

Logline: A prison psychiatrist meets a death row inmate on the verge of his execution who claims to be the only thing stopping the end of the world. As she begins to investigate his predictions, she finds them to be eerily accurate, and that she may be a central figure in the events to come.

Thoughts: Okay, we’re getting into some high concept ideas finally. This sounds good. Love the conflict inherent in the logline (something needs to break). Hernany produced the fun horror comedy, “Ghost Team One,” and was a supervising producer on Ah-nold’s “The Last Stand.” He’s also been on a lot of sets as a crew member. So he’s had some Hollywood experience.

ELSEWHERE

by Mikki Daughtry and Tobias Iaconis

Logline: After his girlfriend dies in a car accident, a man finds his true soulmate, only to wake from a coma to learn his perfect life was just a dream — one he is determined to make real.

Thoughts: Yet ANOTHER high concept. Nice. We’re on a roll here. These are the kinds of scripts writers need to be writing to get noticed. It seems like these two made it to the second round of the Austin screenplay competition with another script, Between, but didn’t advance.

CLARITY

by Ryan Belenzon and Jeffrey Gelber

Logline: What if a world woke up tomorrow to scientific proof of the afterlife?

Thoughts: Okay readers, don’t get your panties in a bunch. Obviously, this isn’t a logline. It’s more of a “teaser,” and I’m guessing the writer didn’t write it. But either way, it’s another high concept idea that has a lot of potential. I’d give it ten pages!

THE POLITICIAN

by Matthew Bass and Theodore Bressman

Logline: A disgraced governor and his underachieving accomplice go on the run from the FBI, U.S. Marshals and a gang of hardened drug dealers.

Thoughts: This is that really big sale from Seth Rogen and Evan Goldberg’s assistants that made big waves a month ago. Another idea that sounds pretty bland on paper. But if the writers are funny, that may not matter. I’m curious if these guys have the goods or if they just got Seth Rogen really high and tricked him into writing a check.

AMERICAN SNIPER

by Jason Dean Hall

Logline: Based on Chris Kyle’s autobiography American Sniper: The Autobiography of the Most Lethal Sniper In U.S. Military History.

Thoughts: This is that big sale that had Steven Spielberg and Bradley Cooper attached for 10 seconds. I read the script and found it to be really really bland. A big problem here is that it’s hard to make a character who’s hiding from all the action interesting. No matter how I spin it in my head, I don’t know how you make sniping dramatically compelling. But people back in the Midwest say this guy is a bona fide hero and that the conservatives will come out in droves to see a movie about him. They just need to do something way more interesting with the story. It’s too bland and too straight-forward now.

THE LINE

by Sang Kyu Kim

Logline: A corrupt border crossing agent must decide what is more important — saving his soul or inflating his bank account — when he discovers a young illegal boy who escaped a cartel hit on the border between the U.S. and Mexico.

Thoughts: Kim is a TV writer who wrote an episode of The Walking Dead and a bunch of episodes of Crash (the TV show). Looks like he’s finally making the jump to features. This one sounds a bit garden variety on first glance.

HALF HEARD IN THE STILLNESS

by David Weil

Logline: A young man who is inadvertently rescued after living 10 years in the basement of the child predator who abducted him, struggles to reunite with his family, while the detective in charge of his case investigates the link between his discovery and the recent disappearance of another local boy.

Thoughts: Hmmmm, Prisoners 2???

TIME & TEMPERATURE

by Nick Santora

Logline: Based on a true story, Dale Julin (a low-level Fresno affiliate morning show host) stumbles upon the biggest story of his life — and though he has reached the midpoint of his career without ever being a “real journalist” — risks his safety and his marriage to uncover the truth that a small atomic bomb exploded in Central Valley, California, during the Korean War — a secret that has been hidden for decades.

Thoughts: Okay, this sounds pretty cool. But I’d ask, what are the stakes? Much like the Reagan assassination script earlier, who cares if he finds out a bomb was dropped 50 years ago? What changes? Santora is a HUGE TV writer and producer, producing such shows as Prison Break and Vegas.

CAKE

by Patrick Tobin

Logline: A woman who’s been suffering from chronic pain since the car accident that cost the life of her child finds the will to go on from the most unexpected places.

Thoughts: Whoa, not going to lie. This one sounded reaaaaalllly depressing and boring. So I went on a hunt for a better logline than the Black List presented. I found this, which sounds much better. This should be a lesson to everyone writing generic loglines! Be more specific! – A dark comedy about a self-destructive woman whose obsession with the suicide of someone in her chronic pain support group leads to an affair with the dead woman’s husband, a drug run to Mexico, and a stop at one of the last drive-in theaters in the country.

THE END OF THE TOUR

by Donald Margulies

Logline: Upon hearing of David Foster Wallace’s suicide, writer David Lipsky recalls his 1996 interview with him.

Thoughts: Wallace is a writer probably best known for his novel, Infinite Jest, which I keep seeing at bookstores and wanting to buy but it’s so damn big. Sadly, these scripts where it looks like depression on top of depression aren’t for me. I need some hope in my stories. Plus this doesn’t so dramatically compelling at all. Someone’s remember someone’s interview? Eek, how do you make that exciting?

NICHOLAS

by Leo Sardarian

Logline: With the Roman Empire on the brink of collapse, a fourth century bishop takes up arms to lead the armies of Constantine the Great into battle against the ruthless emperor, changing the face of Rome and begetting one of the greatest legends in history.

Thoughts: This sounds epic. It’ll all depend on what kind of filmmaker they get to film it. But I like this kind of period piece. If you’re going to do one, might as well make it big! — Sardarian is another writer who came to Hollywood and did a whole bunch of film jobs (casting, production, PR) to grow his network and establish himself in the industry. He then used those contacts when he wrote something great. That’s the way you do it, folks!

MAN OF SORROW

by Neville Kiser

Logline: Based on true events, the story centers on Oscar Wilde who goes from renowned playwright to losing everything personally and professionally.

Thoughts: Okay, I can dig a grandiose tragedy about a famous person. And I don’t know as much about Oscar Wilde as I probably should, so I’m in. Kiser has spent most of life battling whether to pursue film or become a man of the cloth. Right now, film is winning.

DIG

by Adam Barker

Logline: After his villainous father-in-law kidnaps his daughters, Sol, a tough-as-nails mountain man, travels across the frigid Appalachian mountains seeking vengeance.

Thoughts: Our THIRD revenge script. Hey, revenge provides a clear-cut story with a clean goal for the protagonist (kill the bad dude) so it usually works.

THE FIXER

by Bill Kennedy

Logline: A man who works in wealth management, and also has his hands in a number of less than ethical enterprises, begins collaborating with a Los Angeles-based drug dealer. The dealer just so happens to have the man’s son as one of his runners in the drug-fueled LA nightlife.

Thoughts: Honestly, I had to read through this logline 3 times to fully understand it, which is never good. Where are our Scriptshadow logline geniuses to fix this up???

SUGAR IN MY VEINS

by Barbara Stepansky

Logline: A 14-year-old female prodigy finds companionship for the first time when she befriends a handsome older man.

Thoughts: Always seems to be one of these “inappropriate relationship” scripts on the Black List every year. But the prodigy aspect adds just enough of a twist that I’m intrigued. Stepansky has written and directed a lot of shorts and small films, one of which was titled, “I Hate L.A.”

SEA OF TREES

by Chris Sparling

Logline: An American man takes a journey into the infamous “Suicide Forest” at the foothills of Mount Fuji with the intention of taking his own life. When he is interrupted by a Japanese man who has had second thoughts about his own suicide, and is trying to find his way out of the forest, the two begin a journey of reflection and survival.

Thoughts: Our favorite Buried screenwriter and the king of the contained thriller is back! But Chris seems to realize that it’s time to grow a little and this definitely sounds different. I don’t like depressing movies (if you couldn’t tell yet) and don’t like movies/scripts where characters are planning to kill themselves (unless it’s a comedy). But Chris has such a breezy easy way about his writing that I’d still read this.

MAKE A WISH

by Zach Frankel

Logline: A 14-year-old boy with terminal cancer has one last wish — to lose his virginity — and convinces his reluctant football star Make-A-Wish partner to help him score.

Thoughts: If an alien were to come down to earth and learn about the world only through the black list, he would think that every 15 year old boy and girl is dying of cancer. Enough with these ideas! Ahhhhh!!! Although I do like the comedy angle and the idea that he gets a football star to help him get laid. That gives me a sliver of hope. But still.

6

BURY THE LEAD

by Justin Kremer

Logline: A desperate, attention-hungry journalist concocts a story that ironically proves to be true and finds himself engulfed in a dangerous underworld of murder and mayhem.

Thoughts: This sounds good. Reminds me of that old Mel Gibson movie, Conspiracy Theory, a little bit. Kremer made last year’s Black List as well. Congrats, Justin, on two in a row. ☺

FROM HERE TO ALBION

by Rory Haines and Sohrab Noshirvani

Logline: A tragic accident in a coastal English town sets off a chain of violence when a malevolent assassin attempts to punish all involved, including a dirty cop who is intent on covering up the truth.

Thoughts: Some crucial piece of information is missing in this logline that’s making it sound generic. Co-writer Haines has reached the Nicholl Semi-finals a few times and has directed a couple of award-winning shorts. Take your career into your own hands people. Direct some shorts!

FREE BYRD

by Jon Boyer

Logline: After being diagnosed with dementia, a retired fifty-something stunt motorcyclist sets out to perform one last jump.

Thoughts: Hey, I know Jon! One of the nicest writers out there. Excited to see him make the list. And this idea sounds really original. Have never heard of anything like it before. I shall be checking it out! Congratulations, Jon!

BEAUTY QUEEN

by Annie Neal

Logline: An unhappily married woman and her best friend go on a road trip to Las Vegas to compete in the Miss Married America competition.

Thoughts: I don’t know what the Miss Married competition is, so I’m not sure I can comment on this. But it does sound like a script written by women for women, so I’m not going to put my judgment stamp on it!

THE REMAINS

by Meaghan Oppenheimer

Logline: Three former childhood friends with a complicated history get back together to spread the ashes of their friend who recently died.

Thoughts: Death. Spreading ashes. Noooooooooo. Oppenheimer also got on the Black List in 2010 with her script “Hot Mess.”

LAST MINUTE MAIDS

by Leo Nichols

Logline: Two lovable losers run into trouble after they start a service cleaning up the stuff you don’t want your loved ones to find once you die.

Thoughts: Oooh, very clever idea!

PAN

by Jason Fuchs

Logline: A prequel to JM Barrie’s Peter Pan. When an orphan is taken to the magical world of Neverland, he becomes a hero to the natives and leads a revolt against the evil pirates.

Thoughts: I’m going to tell you a secret right now. If you’re ever in a pinch for an idea – incorporate Peter Pan somehow. Hollywood LOVES Peter Pan. I see so many Peter Pan specs sell. You gotta find a unique angle. It can’t just be any old Pan script. But if you do, it will sell!

DUDE

by Olivia Milch

Logline: The story of four best girlfriends who must learn how to move forward without moving on, as they come down off their “high” of high school in this “Fast Times-esque” teenage comedy.

Thoughts: This is so general and so about teenage girls, that I don’t think there’s any chance I would be interested in it. That’s not to say others wouldn’t, but this ain’t my thing.

PATIENT Z

by Michael Le

Logline: In a post-apocalyptic world full of zombies, a man who speaks their language questions the undead in order to find a cure for his infected wife.

Thoughts: Zombies shalt never die! So stop trying to kill them!

MISSISSIPPI MUD

by Elijah Bynum

Logline: In the middle of major financial problems, a down on his luck Southerner’s life begins to unravel when he accidentally runs over and kills a runaway girl.

Thoughts: Well well well, we’ve got the rare DOUBLE OCCUPANT on the Black List. Bynum also wrote the script up above, Hot Summer Nights. Hey, as long as it’s better than Mud (the most overrated movie of the year), I’ll read it!

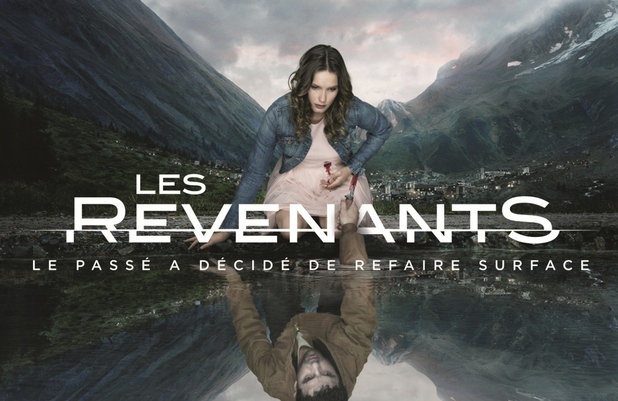

Genre: The Hobbit – Fantasy. The Returned – Supernatural (TV Pilot)

Premise: (The Hobbit: The Desolation of Smaug) The dwarves, along with Bilbo Baggins and Gandalf the Grey, continue their quest to reclaim Erebor, their homeland, from Smaug. (The Returned) A group of people who died in a horrific accident in a remote town, begin to reappear four years later.

About: Reviewing TWO things today. The Desolation of Smaug is part 2 in Peter Jackson’s never-ending Hobbit six-tology. The Returned is a French TV show that was brought over here to the states via The Sundance Channel. It’s being heralded as one of the best shows (some even say THE best) of the year. I’m talking some people believe it’s better than Breaking Bad, folks.

Writers: The Hobbit – Peter Jackson & Fran Walsh & Philippa Boyens and Guillermo del Toro (based on the book by J.R.R. Tolkien). The Returned – Fabien Adda

Details: The Hobbit (149 minutes) – The Returned – 52 minutes

Edit: I’ll put up a post about the Black List tomorrow – so save your thoughts until then. :)

There are very few people in this world who can pull off reviewing a giant fantasy blockbuster sequel AND an obscure French horror TV show, and tie it all together. I am not one of those people, unfortunately. So you’ll have to endure a very confusing Monday post.

You see, the plan was to review The Hobbit 2: Older Legolas’s Return. Problem is, the movie bored me so much that I didn’t know if I had anything constructive to say. So disinterested did I become with the film that I had to come up with things to occupy my brain in order to stay awake.

I noticed, for example, that Evangeline Lilly (Kate from Lost) was in the film. I then remembered that Lilly once dated Dominic Monaghan, another cast member on Lost, who also happened to be… you guessed it (or probably didn’t) a hobbit (in the form of Merry) from the Lord of the Rings trilogy! This odd connection swam through my head for a good ten minutes as I wondered if Peter Jackson auditioned her as just another actress, or if she was on set for the previous movies because of Dominic and THAT’S how she got the part.

But back to the story (I guess). My issue with this movie was two-fold: Too much talking and too much plot. Starting right out of the gate, we get a 7-8 minute scene (not positive on this but that’s how long it felt) of a hobbit sitting in a bar talking to Gandalf.

Now I understand WHY this scene was here. Jackson had to remind the audience (or explain to those who hadn’t seen the first film) what our main characters were going after. But see, this scene highlights one of Jackson’s key weaknesses as a writer. Straight up telling the audience, in a boring manner, what the characters are after is not the only way to do it. There are more entertaining ways to convey info.

Such as doing it on the move!

Start with our characters continuing forward from the last movie and figure out a clever way for them to remind the audience what’s going on. It could be as simple as a dangerous villain-like character stopping them and demanding to know where they’re going (which ends up happening later in the movie anyway). That way you don’t have to waste 7 minutes (7 OPENING minutes – some of the most precious minutes of a film) on something you can slip in in under 60 seconds while we’re hopping along.

And you want to know the funny thing? That opening scene didn’t even achieve what it set out to do! It was supposed to clear up what the goal was, but because there was SO MUCH TALKING, all the important stuff we were supposed to hear got lost in the noise. That’s actually a common beginner mistake – believing that lots and lots of explaining will lead to clarity. It’s always the opposite. The less you say, the more impact the words will have. It’s sort of like a beautifully written song whose lyrics are drowned out by 5 electric guitars, two sets of drums, a synthesizer, a trumpet, and a tambourine. How are we supposed to hear the lyrics with all those instruments hiding the voice?

This became a theme throughout the script. Talktalk talk talk talktalktalk talk talk talk talk. So much freaking TALKING. If that Elf King guy had one more endless conversation with one of the other elves, I was about to stab myself with Orlando Bloom’s chin. Whatever happened to DOING??? Whatever happened to SHOW DON’T TELL?? Isn’t that what makes cinema great? I mean, sure, if we’re watching a Woody Allen movie, talk all ya want. But this is a freaking blockbuster about elves, orcs, bear-men, and monsters! Leave the damn talking to the radio jockeys.

Think I’m being too harsh? Consider this. The Lord of the Rings trilogy is based on 3 books. The Hobbit trilogy is based on 1 book. Yet each Hobbit movie is just as long as its Rings counterpart! Why are we adding 40-some minutes to a typical run-time if the source material is 1/3 the size? It makes zero sense. Which brings us back to WHY it’s 40-some extra minutes. BECAUSE OF ALL THE DAMN TALKING! If the characters did more DOING and less TALKING, this film would actually play out at an acceptable 2 hours.

Anyway, once we got to this Venice-like fishing village, I mentally checked out. I was so bored. I had no idea what was going on anymore (too much talking – I lost track!). And it just verified what everybody said about these films when they were first announced – that they’re not needed. They’re superfluous in the worst way. They’re smaller versions of the original films. If you’re going to make a sequel trilogy, it needs to be bigger and badder than the first one! Or else what’s the point?

Which brings us to The Returned. My favorite new show! I feel really good about trumpeting this one because I was pretty nasty to the French during my “French Week.” Mon amis, all that has changed! Whereas everything about the Hobbit world was tired and familiar, everything about The Returned feels fresh and different.

The opening pilot takes place in a remote mountainous French town where (big spoiler) we see a school bus lose control and shoot over a cliff. Everyone on the bus is killed. However, four years later, a mother and father, still grieving the loss of their child, are shocked when their daughter walks in the house like nothing happened. Naturally, the parents are beyond freaked out, and are so scared that this hallucination is going to end, that they do everything in their power to pretend like nothing’s changed (not easy since the parents have since divorced).

Also returned are a young man looking for his girlfriend (who has since married someone else and had a child) and a young freaky-ass boy, who follows a lonely woman home and convinces her (without saying a word, mind you) to let him stay with her. To round matters out, a young woman with no connection to the bus is murdered inside an underground walkway.

While much of what carries The Returned is the creepy melancholy directing style, the writing is just as stellar. Just like any good television pilot, the show starts out with an amazing teaser (spoiler). You are not expecting that bus to go shooting off that cliff. The writer then knows how much power there’ll be behind each “returned” character, so they milk each one, allowing your anticipation to grow as each “dead” kid is reunited with their loved ones.

That’s a nice trick every screenwriter should know. The amount of time you can milk a scenario is directly proportional to how big that scenario is. The dead coming back to their non-expectant families after four years? – that’s big enough to milk the shit out of (the long walk home home, the approach to the house, hanging out in the kitchen and getting food – screenwriter Adda really takes his time reuniting the family members). We’re dying as we can’t wait to see how the parents will react to seeing their kid again.

The script is also a great reminder of how important the “remote” scenario is to a story. I mean, it’s not for every story, but putting your characters in the middle of nowhere increases that feeling of helplessness that can really unsettle an audience. It’s a big reason Lost worked so well, and why movies like The Shining, Let The Right One In, and The Thing were so good. Cut your characters off from the rest of the world, and you add a heightened sense of fear.

I also loved how interesting the choices were. Remember that tidbit in my “Voice” article from last week? How a big part of your voice is reflected in your choices? (Spoilers) Here, they could have done the obvious and had people from the bus crash start coming home left and right. But then we learn the weird kid WASN’T on the bus. He was standing in the road and made the bus crash. So then who is he? We also have a murder in the middle of the script from two characters who had nothing to do with the bus. That also throws us off guard. These are the unexpected things that keep audiences tuning in every week.

I could keep going but instead I encourage you to go watch this show right now. It’s the first truly exciting thing to hit TV in years.

Desolation of Smaug rating:

[ ] what the hell did I just watch?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the price of admission

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

The Returned

[ ] what the hell did I just watch?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth watching

[xx] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Too much dialogue can dilute your point. When having your characters convey key plot points, don’t over-state them. Keep them simple. Tell the audience the information they need to know, then move on.