The worst comedy I’ve seen in years.

Genre: Comedy

Premise: While bringing Alan to a treatment center, the Wolf Pack is bombarded by a Vegas heavyweight, who tells them that they must bring him their nemesis, Chow, or Doug will be killed.

About: Director Todd Phillips shared writing duties on this one with Hangover 2 scribe, Craig Mazin. Mazin was scraping the bottom of the comedy barrel for awhile, writing a couple of “Scary Movie” sequels, before getting a huge break to work on Hangover 2. He parlayed that into the hit film, “Identify Thief,” and now Hangover 3.

Writers: Todd Phillips and Craig Mazin (original characters by Jon Lucas and Scott Moore)

Details: 100 minutes

Oh my.

There’s this song by the Lumineers that’s out right now where the chorus goes: “Ho!… Hey!”

I would officially like to change those lyrics to: “No!… Way!” in response to this movie.

I don’t want to go overboard here but people need to be held responsible for this atrocity. I’m not going to ask for the equivalent of the Nuremberg Trials but I kind of want to ask for the equivalent to the Nuremberg trials. Craig Mazin was in full “Scary Movie” mode here. Todd Phillips decided to make a movie that didn’t have a single laugh in it.

This was bad, folks. Really really really really bad.

Like, those guys owe me my money back, bad. This wasn’t even a movie. I understand the concept behind cash grabs. But these humor rapists went a step further and laughed in our faces as they stole our money. So I take what I said earlier back. There was one joke that worked. The one that was on us.

The plot? Okay, um, sheesh. It went something like this. Alan (Zach G.) is acting weird so everyone stages an intervention so he’ll go get help at a treatment facility. Um – WHAT?? That’s not how interventions work. Interventions are for when you drink too much or do too many drugs. When you’re, like, addicted to something. So not five minutes in and already the plot doesn’t make sense.

So the “Wolf Pack” (Alan, Doug, Stew, and Phil) is on its way to this facility when John Goodman runs them off the road and tells them, inexplicably, that Chow stole money from him a long time ago and since they kind of know Chow, he’s taking Doug and giving them 72 hours (because “why not” 72 hours!) to find Chow and bring him to him.

They eventually meet up with Chow in Tijuana (because “why not” Tijuana!) who quickly figures out what they’re up to and decides to help them. So they go to Chow’s ex-house where he was storing the gold he stole from John Goodman, break in, and steal it. But just as they’re all about to leave, Chow locks them in and takes off with the gold! Oh no!

What’s worse, they’re snagged the very next day by John Goodman, again, who informs them that they just broke into HIS HOUSE and stole HIS GOLD. That wily Chow tricked them good! So now they have to get Chow again, who’s driven off to…. VEGAS. Oh rats! It’s going to end where it all began. Or something. Kill me now. It cannot get any worse than this. I’m done with this summary. It pains me too much to relive this atrocity.

Okay, probably the most bizarre thing about this script is that either Phillips or Maizen seems to hate animals. As you’ve probably seen in the commercials, Alan is driving a giraffe he just bought down the highway. This is the first scene of the movie. Well, what you don’t see is the giraffe’s head gets decapitated by the overpass – WHICH WE SEE – and it goes flying up and landing in the windshield of the car behind them.

What. The. Fuck.

You just gruesomely killed a giraffe – one of the most beloved animals on earth – in your very first freaking scene? Are you that stupid? No, seriously. Are you that stupid? One of the first things they teach you in screenwriting is not to kill animals onscreen. So Phillips and Mazin take a giraffe and decapitate it? And think it’s funny? Right at that moment, Miss Scriptshadow turned to me and said, “I want to leave.”

But that’s not it. After that wonderful scene to start the comedy, in the very next scene we watch as Alan’s dad has a heart attack and dies! So we just watched a giraffe get killed, which is then followed by a character dying of a heart attack. This is a comedy, right? No, seriously. This is a comedy, right? I’m just checking because I thought comedies were supposed to be funny. Not have a bunch of killing and dying.

Oh, but there’s more! Chow kills a chicken later, smothering it with a pillow until it stops moving. Then snaps a couple of dogs’ necks, which was thankfully off-screen, although I’m sure Mazin originally had it onscreen and someone with some sense finally came to these morons and said, “We can’t have this much animal-killing in a comedy.” Phillips and Mazin were likely pissed but allowed it in a compromise.

But that’s just the beginning of the problems here. The beauty about the original Hangover’s premise was that all the exposition was taken care of in 30 seconds. Doug’s missing. We need to find him to get him back to his wedding in time, but we were so wasted last night that we don’t remember anything. That was it! That’s all we needed to know, which allowed the writers to just have fun with the premise.

Of the first 60 minutes of Hangover 3, I’d say about 30 minutes of it is dedicated to exposition. We have Alan needing an intervention, then finding a place for him to go to, then needing a reason for the Wolf Pack to have to take him, then Chow breaking out of jail, then John Goodman talking forever about how Chow stole money from him, then why we need to go down to Tijuana, then why we need to break into this house, then why we need to go back to Vegas. There was rarely a scene where exposition wasn’t needed. Which was why the movie was so incredibly effing boring. Exposition = boring.

And the thing about exposition is that you use it so the audience understands what’s going on. The irony here, then, is that the more they used it, the more confusing things got, because audiences hate exposition. They hate constant explaining. So they tune out if there’s too much of it, and you’re actually accomplishing the opposite of what you set out to do.

Then there was Alan and Chow. It’s important to understand how to use characters in screenwriting, something Mazin apparently forgot. There are certain characters who are good at certain things, and therefore should only be used for those certain things, and characters who are good in small doses, which is why they should only be used in small doses.

Alan is the kind of character who should never be driving a movie. He’s the kind of character who’s best when reacting to situations. He needs to be off to the side, saying funny things here and there. That’s when he’s at his best. The second you try to make him the main character, you’re done. Because he was never meant to be a main character. Quirky super-weird characters just don’t have the meat necessary to drive a story. And therefore, Mazin and Phillips take one of the funnier comedy characters of the last decade and make him annoying. Cause there’s so damn much of him.

Speaking of “so damn much,” the same can be said of Chow. Chow is a classic “small doses” character. He needs to be popping out of trunks naked, not sitting in apartments giving long monologues. Chow sounds weird when he talks a lot. His accent isn’t as funny. His dialogue feels forced. Because he was NEVER MEANT TO TALK THAT MUCH. This is the case of the writers misreading what made Hangover good. Yes, Chow and Alan were hilarious in the initial movie. But they were hilarious for the specific reason that they were fitting their roles. Take them out of those roles and they don’t work anymore.

Many people have said that the actors didn’t even look like they wanted to be in the movie – that they all knew this was a cash grab and therefore phoned it in. I agree that they look bored, but I don’t think it’s because it was a cash grab. I think it’s because the writing sucked. How do you get into your character when what your character is doing doesn’t even make sense? Or when you can’t justify the existence of your character in a scene? Or in the movie! You can’t make something out of nothing. You can’t make something feel real and honest when nothing about them is real or honest.

I suppose I could go on here, but what would be the point? This was a misfire on every level. I actually liked The Hangover 2. Sure, they ripped off the plot of the first film, but at least it was a plot that worked. This was a never-ending mess of bad plot points. So much so that I’m bringing back an old rating that’s been dead on this site for awhile. I’m sorry, this was that bad. Mazin and Phillips owe me and everyone else who saw this movie our money back.

[x] trash

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Beware of over-plotting, which you’ll know is happening if you’re constantly having to use exposition throughout your screenplay. Usually, the best comedy premises are set up quickly. If you’re still having to explain where your characters are going and why halfway into your story, you’re probably over-plotting your script.

This is your chance to discuss the week’s amateur scripts, offered originally in the Scriptshadow newsletter. The primary goal for this discussion is to find out which script(s) is the best candidate for a future Amateur Friday review. The secondary goal is to keep things positive in the comments with constructive criticism.

Below are the scripts up for review, along with the download links. Want to receive the scripts early? Head over to the Contact page, e-mail us, and “Opt In” to the newsletter.

TITLE: Fatty Falls Down, Again

GENRE: Dramedy

LOGLINE: A young man enrolls in film school and befriends a funny classmate who claims to be the reincarnation of Chris Farley. Still haunted by the suicide death of his best friend, the student vows to keep this self-destructive “Chris” from killing himself.

TITLE: KIng of Matrimony

GENRE: Drama/Comedy

LOGLINE: A loving husband and father must maintain a series of affairs in order to save his happy marriage.

TITLE: Rumspringa

GENRE: R-rated Comedy

LOGLINE: When a dimwitted Amish man-child gets a message from God that his long lost brother is living a life of sin in Miami, he solicits two Amish teens to help find his brother and save him from eternal damnation; upon arrival, the threesome unknowingly botch a drug deal and realize that if they don’t adapt to the outside world quickly, they’ll never get home alive!

TITLE: Ship Of The Dead

GENRE: Vampire/Thriller

LOGLINE: After their medical rescue aircraft crash lands above the Arctic Circle, a terminally ill flight navigator must lead the crew to survival in the face of plunging temperatures, the impending arrival of 6 months of permanent darkness – and a horde of vampires taking refuge in a nearby shipwreck.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: Finalist in the Peachtree Village International Film Festival.

TITLE: BLACK WEDNESDAY

GENRE: Comedy/Coming of Age

LOGLINE: Three different graduating classes return to their small New Jersey town for a night of awkward reunions and drunken debauchery on the biggest bar night of the year – Thanksgiving Eve.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: Oh man, I wish I could give you this guy’s query letter. There’s a hilarious story about being an assistant to a producer and having to save his boss’s ass when a major director came in to get notes on a pilot the boss hadn’t read. I can’t give you that but here’s the beginning of his query: I know you asked for a paragraph, but let’s keep this shit sparse. Here are the bullet points. – Depending on what source you check, Thanksgiving Eve is either the single biggest (or second biggest) bar night of the year. Now think how many movies have ever been set on this night. Can you even think of any? HOW IS THAT POSSIBLE? – This year marks the 20th year since DAZED AND CONFUSED was released, the quintessential one night, ensemble, coming of age comedy. DAZED AND CONFUSED set on the biggest party night of the year. That’s my pitch..

Amateur Friday Submission Process: To submit your script for an Amateur Review, send in a PDF of your script, a PDF of the first ten pages of your script, your title, genre, logline, and finally, why I should read your script. Use my submission address please: Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Your script and “first ten” will be posted. If you’re nervous about the effects of a bad review, feel free to use an alias name and/or title. It’s a good idea to resubmit every couple of weeks so your submission stays near the top.

Genre: Psychological Thriller

Premise: (from writer) After a radical exorcism leaves a possessed teen in a coma, a psychologist reluctantly helps the clergymen, who performed the rite, wake the child, but soon suspects foul play and finds himself trapped in a secluded monastery with only one person to turn to for help: his newly awakened patient.

About: Inhuman won the Amateur Offerings Weekend two weeks ago. Submit your own script for Amateur Offerings via the instructions above.

Writer: Steffan Ralph DelPiano

Details: 96 pages – 4/21/2013 draft

Last year I met with this company that holds preview screenings for studio films to find out what’s wrong with them. They have ten years of data on hundreds of films, and they can basically tell you exactly what an audience will or won’t like at any particular moment in a film. For example, they explained to me something about how an audience has never liked when the best friend character turns on the hero (I’m not exactly sure that was the example – but it was something like that).

Their research is also so extensive that they can predict exactly how much money a movie is going to make. They know which genres do the best. They know which type of heroes garner the best response from an audience. You’ve probably heard of these people before. And I think there was even an article in the New York Times about them last week (I’m guessing it’s the same people I met with – but I still haven’t read the article – we met because they wanted to expand their business into screenplays).

Out of curiosity, I asked them which specific kind of movie, in their research, generated the best return on investment. The president thought about if for a moment, as he mentally cycled through their research, and I had to admit I was kind of surprised. If I were a studio head, this would be the first question I’d ask this company. Yet he appeared to have never been asked the question before. But the light finally came on, and he defiantly said, “Exorcism movies.”

I thought about that for a moment and it made complete sense. Exorcism movies are incredibly cheap to make, and also incredibly easy to market. People will always go see exorcism movies. Since that meeting, I’ve always kept my eyes open for a good exorcism script. One of these days, I’m going to produce a movie, and I’d prefer it be a movie that actually makes money. So when I started reading Inhuman and I realized I hadn’t checked the page number for 30 minutes (note: I usually check the page number within the first 10 pages), I knew I was onto something good.

Inhuman centers around 39 year-old Simon, a psychiatrist specializing in defense mechanisms. Simon is kind of arrogant, sort of into himself, and doesn’t have time for tomfoolery. Which is why he’s agitated when a priest comes along asking him to help him save a young man. A young man who happens to be possessed.

Naturally, Simon doesn’t believe in any of that nonsense, so he ignores him. But the Father and his Church Team are persistent, hounding him with letters and videos that show this young man, Peter, doing and saying terrible things that couldn’t possibly be from a human being. Simon continues to refuse, but after a surprise attack by one of his patients, he has a change of heart.

In order to make sure the creepiness-factor is raised to level 12, Peter is being held at an abandoned asylum with our priest, Father Bryant, and his right hand woman, Sister Collette. Simon’s immediately able to make a connection with Peter, whom he believes is a paranoid schizophrenic, but Peter keeps saying and doing things that just don’t make sense. He knows what Simon is thinking, what he’s feeling, what he’s doing when he’s not with Peter. Simon eventually starts to question his diagnosis.

(Spoiler) Eventually, Simon learns the truth. He IS Peter. Or, more specifically, Peter’s last level of defense that the possessing demon must defeat. Simon is essentially keeping the demon from fully possessing Peter’s soul. Obviously, this is a lot to take in. I’m sure it isn’t easy learning you’re not real. But Simon eventually jumps onboard with the plan and attempts to rid the demon from Peter’s body.

Yesterday I talked about breaking the rules. And I’m happy to report that Steffan does break the rules here. Or, if not break the rules, he takes one hell of a chance. This isn’t your traditional exorcism story. It becomes more of a psychological, and even METAPHYSICAL, story. And to that end, I give Steffan credit. He did not go down the obvious path, and for that reason he has quite the original screenplay.

Unfortunately, just because you do something different doesn’t mean it was the right thing to do. As I stated yesterday, the bigger the chance you take, the bigger the chance at failure. For 60 pages here, I was riveted. I was thinking, “Oh my God, I’m going to call Steffan after this, we’re going to raise money, and we’re going to make this movie!” I NEVER say that when reading a script. That’s how into it I was.

But as soon as Simon becomes Peter’s defense mechanism – as soon as he’s no longer real – the story starts to get murky. I wasn’t always sure what Simon was going after, and I began asking questions like, “Well then, where was Simon during the first half of the movie? His office? All those people he dealt with? None of them were real??” It didn’t make sense. And of course, “If you find out you’re not real, what’s the point?” I mean, why try to save anyone? If I found out I wasn’t real, I’d go sit on my couch and be super freaking bummed out. I don’t care if the person I’m inside of is possessed by either the devil, or an In and Out addiction.

It reminded me a lot of that movie, “Identity” with John Cusack that came out a decade ago. It started off with all these great questions, but the more we found out, the less interesting it became. At one point, Father Bryant kills Collette and I don’t know WHAT’S going on anymore. Why is this priest killing the one woman he knows and trusts the most?

If I were a producer giving notes on this script, I’d say to Steffan, sadly, that we’d need to get rid of the stuff that makes this unique. Drop the metaphysical third act and see if we can come up with something more “real,” more “solid.” If I’m not sure what the consequences are for anybody because certain people aren’t real, I’m not sure we care about what happens to them.

The stuff that resonated with me was this showdown between ultra-smart Simon and possessed Peter. It looked like we were going to watch a prolonged dragged-out war between these two. And that’s what I wanted to see. But we only get a couple of scenes with them duking it out before the world turns upside-down with the super twist of Simon not being real.

Sometimes we can get carried away with our twists. We want to go so big, so shocking, that we write a twist in that we can’t write ourselves out of. I think that may have been what happened here. Despite that, I think Steffan’s a really good writer and that this is the kind of script that could get him some meetings around town (if he hasn’t had those meetings already). It does lose itself in the third act, but those first two acts are damn good. And two-thirds of good has to equal a “worth the read” right?

Script link: Inhuman

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Have a third person come into a scene to be a ticking time bomb, pulling at our main character while he’s dealing with something/someone else. On page 8 here, there’s a scene where the Church Team is asking Simon to help them. At that moment, Alexis, Simon’s assistant, pops in to inform Simon that Group is starting. As the team tries to explain Peter’s possession to Simon, Alexis keeps saying, “So should I start without you or…?” It adds an element of immediacy and conflict to what would otherwise be a very straightforward scene: A group asking our main character to help them. So look for those opportunities to introduce a distracting element (or ticking time bomb) into a scene to spice that scene up.

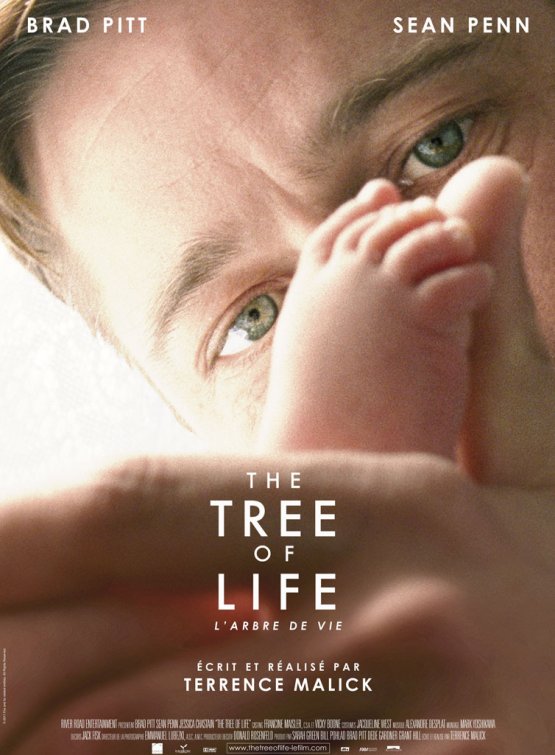

The current rule-bending king – Malick.

The current rule-bending king – Malick.

Art.

The essence of purity. It should be intrinsic, effortless, natural. A poem. A painting. A short story. All of it should emerge from that illogical, dreamer part of the brain. Write down whatever exists within the deepest recesses of your mind and then (and only then) have you been true to your artistic self. Containing it, rearranging it– sticking with the common word, scenario, characters, etcetera, with which a viewer or reader is all the more familiar, and you are no longer an artist. You are a machine, bottling up art into a series of rules.

It’s a debate that’s been going on way before screenwriting. Should there be “rules” or “guidelines” to art? To me, the answer is obvious. It is a resounding “yes.” But to many, the belief is that you’re defeating the purpose of art if you’re trying to structure it. You’re restraining that part of yourself that expresses creativity. There should be no filter on our imagination. It should exist unimpeded.

Here’s the way I see it. Let’s say you have two writers. One of these writers has been told to keep his scenes under three pages and to focus mainly on pushing the story forward with each one. The other writer has been given no restrictions whatsoever. Have your scenes last as long as you want them to. Focus on whatever you think up at the time, regardless of the story. All else being equal, the focused writer is going to write a better script. It’s rules (or “guidelines”) like this that make us better writers, which results in better screenplays. Therefore, rules are an essential component to art.

Here’s the catch, though: I think every script should break the rules in some significant way. That’s what makes a script unique – its deviation from the norm. Look at Pulp Fiction. It’s a story told out of order and many of the scenes are ten minutes long. Those two “rule-breakers” are what made Pulp Fiction feel so unique. BUT it doesn’t mean Tarantino wasn’t following ANY rules. For example, he made sure each and every scene was packed with conflict so it could sustain a ten-minute running time. “Conflict” is one of the “rules” many consider essential to writing a good screenplay.

The idea here is that you want some semblance of structure to dictate your story, but you pick two or three areas where you go against the mold, where you do things you’re “not supposed to do.” This is what’ll set your script apart. And it’s essential. Because if you write a movie where you follow every single rule to the T, you get a safe “by-the-numbers,” generic screenplay.

It should also be noted that the places where you break the rules will likely be what either makes or breaks your screenplay. Whenever you break a rule, you swim off into unchartered waters. You’re doing something that isn’t usually done. And since there’s no blueprint for the less-traveled path, you’re usually on your own, figuring things out as you go along. Breaking these rules then becomes a huge gamble. And the more rules or the bigger the rule you break, the greater the gamble is. It’s the equivalent of putting all your money into that young up-and-coming company. It can either tank, resulting in you losing everything, or succeed, turning you into a millionaire. You just don’t know until you hand the script to someone else.

With that in mind, here’s what I hope will be a helpful guide to breaking the rules with your screenplay. These are seven of the more common rule-breaking approaches and how to make them work for you:

1) The No-Holds-Barred – This is probably the most dangerous path you can take as a screenwriter. You go into the writing with only the barest sense of what you’re going to write about. There is no plan, no outline. You just feel like writing about something and you let your imagination take you wherever it wants to go. It’s the “David Lynch” approach, if you will. Note that these are typically the worst scripts that I read (by far), and that the only real people who succeed at using this method are also directing the film (like Lynch). I’d strongly advise against this path. Then again, it usually results in the most original material.

2) Out of order – This is one of the more common forms of breaking the rules, and therefore there’s some precedent for how to make it work. You simply tell your story out of order. Movies like Pulp Fiction, 500 Days Of Summer and Eternal Sunshine Of The Spotless Mind succeeded quite well with this device. All I’ll say is if you tell your story out of order, make sure there’s a reason for it. If you do it just to be different, it will show. What was so genius about 500 Days of Summer was that it showed you the greatest and worst moments of a relationship crammed up against each other, something we never get to see in a romantic comedy or love story. So there was a purpose to the choice. I can tell pretty early when there’s no reason for a writer to be jumping around in time in his script. They’re just doing it to be edgy or, they hope, original. But it often ends up feeling so random that I check out before the script is over.

3) Multiple protagonists – You’ve seen multiple protagonists in movies like Crash and Breakfast Club. The reason you should avoid multiple protagonists if possible is because audiences like to identify with and follow a single hero in a story. Once you have two people (or three, or four) to follow, you start losing that close connection that’s required to get sucked into a movie because your interest is being pulled in too many directions. The exception here, and the way to make this work, is to sculpt amazing characters. Each character should have their own goals, dreams, flaws, fears, compelling backstory, quirks, secrets, surprises. If you can make each one of these characters deep enough so that they could theoretically carry their own movie, you can get away with a multiple protagonist story.

4) No Goal – To me, one of the biggest rules you can break, and one that almost always spins the story out of control, is not having a goal for your main character. Without a goal, your main character won’t be going after anything, which means he won’t be active, which means the story will feel like it doesn’t have a purpose. One of the most famous movies to do this is The Shawshank Redemption. Our hero, Andy, is just existing. He’s just trying to make it through life in jail. I believe the key to making these movies work is conflict. You gotta have a lot of conflict. Andy is attacked repeatedly by the rapist, Boggs. He’s thrown in the hole for playing music. His one witness who can free him is murdered. And there is the constant fear that the dictatorish warden and his corrupt officers will take you down if you step out of line. You have to be tough on the protag, make him feel the pain of life, and we’ll watch to see how he deals with it.

5) The anti-hero – Most people will tell you your hero should be likable. And for the most part, I agree. If we’re rooting for your hero, we’ll be invested in whatever story you tell us, whether that story is big, small, slow or fast. But there are a few dozen movies out there with anti-heroes as the lead that have done really well. You have Travis Bickle from Taxi Driver, Lester Burnham from American Beauty, or Riddick from Pitch Black. In my opinion, the way to make these characters work is to a) make them dangerous and b) don’t hold back. You feel at any moment that Bickle might fucking go ballistic and rip your head off. Or with Riddick, the guy is a serial killer. If we’re a little bit scared of these people, we’ll be fascinated by them, and we’ll want to know what they’re going to do next, which is the key to getting a reader to turn the pages. Also, don’t hold back. You have to take some chances with these characters or else what’s the point of writing an anti-hero? Lester Burnham is trying to nail his 16 year old daughter’s best friend. That’s a HUGE chance, and it’s one of the reasons this movie remains so memorable – it didn’t hold back.

6) The long script – It’s one of the most “set-in-stone” rules there is in spec screenwriting: Don’t write more than 120 pages. Yet there are plenty of great, long movies out there. So, how does one get away with breaking this rule? I know this is going to sound like a cop-out but the truth is: great writing. The longer your screenplay is, the better the writer you have to be. Because remember, it’s hard enough to keep a reader’s interest for FIVE pages. Look back at Shorts Week if you don’t believe me. So each additional page you write, you’re increasing the chances that the reader is going to lose interest. In my experience, the long scripts that do well, such as Titanic or Braveheart, show skill in character development, dramatic irony, scene-writing, a keen sense of drama, knowing when to up the stakes or add a twist, theme, conflict, dialogue, you name it. They’re usually INCREDIBLY STRONG at 90% of these things, which is what allows the writers to write something both long and good. A lot of writers (especially beginner writers) BELIEVE they can make a 180 page script work, despite barely understanding any of these things. I (and fellow readers) are the unfortunate recipients of these delusions of grandeur. They are never ever good. So my advice to you would be: Don’t write a long script unless a) you’ve already written 10 full screenplays and b) you’ve found some level of success with your work (some sort of proof that you can tell a good story – a sale, an option from a major company, a win in one of the major contests, etc).

7) The Act-less script – A close cousin to the “No-Holds Barred” and the “No Goal,” the act-less script shuns traditional 3-Act structure in favor of letting the characters and one’s mind take the story wherever it will go. Terrance Malick movies are well known for this, and to a lesser degree, Sophia Coppola’s (watch “Somewhere” to see what a truly act-less script looks like). It should be noted that the 3-Act structure is built on the idea of a hero with a goal, as the first act establishes that goal, the second act is about him pursuing it, and the third act is either him succeeding or failing. So if you don’t have a character with a goal, you’re more likely to run into an act-less screenplay. If you’re going to shun traditional act-breaks, it’s important, in my opinion, that you ask a lot of dramatic questions and include your share of mysteries in the story. Since we’ll want these questions and mysteries answered, we won’t be as concerned with the lack of a traditional setup and strange story direction. 2001: A Space Odyssey shuns traditional structure, but it finds a substitute for that structure to keep our interest in the mystery of the monolith.

The above is a look at some of the bigger rules you can break, but they are by no means the only rules. There are lots of smaller rules to play with like stakes, urgency and conflict. I mean, we’re taught early on in this craft to never come into a scene too early. Well, you can obviously break that rule and come in a lot earlier if it fits what you’re trying to do with the scene. The message I want to get across is that you should break these rules from a place of knowledge and a place of purpose. Understand the rule you’re breaking and have a reason for wanting to break it (which means studying screenwriting as much as possible). Memento is a great example. It’s about a guy who keeps forgetting. Well, if we tell that story in order, then we know way more than our character knows. Tell it backwards (break the rule) and we know just as little as him, which is an approach that fits our main character way better.

Yes, you can go with your gut and make choices knowing nothing about how storytelling works and become that lucky 1 in a million shot that creates something genius. But it’s more likely that the opposite will happen. In my experience, the people who have written these amazing rule-bending screenplays have been in the business for a long time, guys like Alan Ball and Paul Haggis and Charlie Kaufman. Tarantino came out of nowhere, but he’s like the exception to the exception to the exception (and it should be noted he’d seen just about every movie ever made before writing Pulp). I think as long as you’re being true to your own unique voice, to the way you (and only you) see the world, you can still write a script that largely follows the rules and it’ll still come off as original. But you definitely want to break SOME rules along the way. How you do so will largely determine the way your script stands out from the rest.

Before Star Trek Into Darkness, before Lost, JJ Abrams wrote a draft of Superman. This is that draft.

Genre: Superhero

Premise: A slightly reimagined Superman origin story which includes an enemy from his home planet coming to earth to take him down.

About: This is JJ Abrams Superman entry, written in 2002, back when JJ was just your average TV show producer, finishing up work on Felicity and starting up work on Alias. The show that would make him a household name, Lost, was still just a twinkle in his eye.

Writer: JJ Abrams

Details: First draft (July 26, 2002) – 138 pages

Superman is still stinging from its horrible previous installment, which very well may have destroyed Bryan Singer’s reputation. The film was just so…forgettable. And badly written. Nothing made sense. Superman, who looked 25, had supposedly left earth for ten years? So he left when he was 15? Already I’m confused. Then nothing really happened. I couldn’t tell you what the story was about. There were no stand-out scenes. Superman was horribly miscast, as was Lois Lane.

I think the scene that epitomized the screw-up for me was the shuttle scene. It didn’t have anything to do with anything. What I mean by that is: it wasn’t woven into any sort of plot. It was just this standalone short movie of Superman saving a shuttle.

I said then that if they were ever going to reboot Superman and get today’s audiences interested, they were going to need to go darker like Batman. I know, I know. That’s “not Superman.” But it’s what audiences are digging, and Superman needed a makeover to appeal to today’s youth. I haven’t seen the movie, of course, but Zach Snyder’s version already looks a thousand times better than that previous abomination.

Which brings us to this draft, which I’ve heard at least partly inspired the most recent movie. But let’s face it. That’s not the reason I’m reviewing it. I’m reviewing it because it’s the JJ Abrams draft. I just had to know what he would’ve done with Superman. And the results are both encouraging and…not so encouraging with an ending so sacrilegious and “out-of-left-field” that I’m pretty sure it was born out of JJ’s first experience with peyote.

JJ’s Superman is basically an origin story with a few twists. It starts out with an awesome battle between Superman and an alien baddie named Ty-Zor from his home planet. They’re throwing each other through buildings, that sort of thing. And Superman is basically getting his ass handed to him.

Eventually we cut back to Krypton and get a detailed look at the civil war going on there, with 100 foot tall robot machines shredding up Kryptonians like a top chef. We get the familiar scene with Supes’s dad putting him in the spaceship, sending him to earth, where he lands at the Kents’ farm, where he grows up with them and yadda-yadda-yadda.

Where the script starts deviating from lore is that it makes Lex Luthor the head of the CIA. Lex is obsessed with UFO phenomena and is trying to convince his bureau to spend more time and resources on it, convinced that little green men are going to become a threat to earth at some point and they need to be ready for it. When a young new reporter, Lois Lane, writes an article about Luthor’s exploits, he has no choice but to tell the world that the U.S. has actually FOUND a UFO.

This freaks Superman (now Clark Kent) out, since he figures Luthor may be referring to him. And he doesn’t want any part in being exposed. Eventually, Luthor’s obsession with UFOs starts to piss the bureau off, and they fire him. Well, you don’t fire Lex Luthor and not expect consequences. Luthor eventually finds and teams up with Ty-Zor, who’s come to earth specifically to kill Superman. Superman may be super and all but (spoiler) he’s apparently no match for these two and is KILLED. Yes, Superman dies.

Or does he?

Eventually we learn that Superman isn’t dead at all, and comes back to take down Luthor, who’s since been awarded the planet by Ty-Zor. Finally the truth is revealed about Lex Luthor and the reason he’s so obsessed with aliens. Turns out Lex Luthor IS AN ALIEN. He’s from Superman’s home planet and has been hiding here. Which results in a final flying city-wide battle between Superman and… Lex Luthor? Holy origin-destroyer Batman. What the hell just happened??

Oh sheesh. Where to begin…

First of all, I’m convinced my man-crush JJ Abrams had nothing to do with this bizarre choice to make Lex Luthor an alien. Some producer came up with that idea. I know it. One thing good writers know is when they’ve gone too far. Or when a choice is too ridiculous or not believable. They just have an intricate feel for what works and what doesn’t. JJ had been working as a screenwriter for a decade at this point. I just don’t think he would’ve personally incorporated this bizarre choice into the story. Maybe I’m in denial. But I can’t accept it. And whoever DID come up with that idea needs to be escorted out of Hollywood permanently.

As for the rest of Superman, I think the challenge for this franchise has most recently been about making it current. It was designed in a different time. We don’t have the “aww shucks” newspaper photographer anymore. Heck, we don’t even have newspapers anymore! Combined with this need for comic book nerds to keep Superman “pure,” it’s just really hard to update it. JJ does his best, but the story still seems stuck in the past.

In particular, the gears of the screenplay seemed more focused on getting in all the necessary “lore” as opposed to just telling a story. Gotta get in the introduction of the suit and cape! Gotta get in that Lois Lane-Superman interview for the paper! Gotta get in the kryptonite intro! Instead of just a naturally flowing story, the screenplay seems designed around artificially incorporating these elements.

The truth is, when you’re telling an origin story, you’re dedicating 40-70 pages of your script to setup alone. And no matter how interesting that setup is, it’s still setup. The audience wants to see the plot get going. Singer tried to do this in the last Superman, by nixing the whole origin story in favor of sending Superman home then bringing him back again, but it was the wrong story element to use, as it was simply too confusing and clunky.

When JJ’s plot gets going, it sort of loses its way as well. Part of the problem is we have two villains here. Now I’m all for double the villain-ry. It’s fun to see a superhero have to take down two assholes instead of one. The problem is these villains never quite gelled together. It felt more like JJ was trying to decide which villain he liked best as he went along. And that may have been the case. Remember, this was a first draft. But I didn’t know where to focus my attention. Was Luthor the more important guy to take down? Or was Ty-Zor?

I think what Nolan did with Batman Begins was kind of genius. He didn’t introduce the best villain of the franchise in the movie. He waited until the second movie to do that. While it’s hard to imagine a Superman movie without Lex Luthor, Ty-Zor was a pretty damned worthy adversary. I mean this guy is throwing Superman through buildings ‘n shit. We just should have built a story around him and brought in Lex for the sequel.

Despite the unending amount of setup here, JJ does manage to plug in a lot more action than Singer’s abysmal version. We have the Air Force One scene (which has since been ripped off numerous times), the Ty-Zor/Superman battle, the Superman mech-machine battle, and just some really imaginative cool scenes back on Superman’s home planet. Those things almost saved the script, but in the end, this messy first draft hadn’t figured itself out yet. Maybe JJ did it with the next one. But any script that has Lex Luthor with the same powers as Superman is going to be a fail in my book.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: I love reading scripts like this because they remind me of how influenced we are by the moment. Whenever we write a script, we write through the filter of “right now,” of what the world is talking about, of what movies everyone’s watching, of how the writers of these movies are approaching their stories. JJ’s Superman feels very much like someone writing a script in 2002. It’s an origin story (just like X-Men from 2000 and Spider-Man of 2002). Just like X-Men, Superman’s flaw is that he believes he’s a freak, which is the reason he doesn’t reveal himself. There’s not a lot of originality here. For this reason, I encourage you not to be too influenced by the moment. Don’t write what everyone else is writing, or be swayed by the current trends. Try to write something that’s wholly unique, that, if looked back at 10 years from now, would stick out as its own thing, as opposed to just another version of what everyone else was doing.