So I just read a cool story the other day (I believe on Slash-Film) about how George Lucas was stressing out over the release of Star Wars. He visited buddy Spielberg on the set of his current production, “Close Encounters” and was so impressed by the grandiosity of it all and was so convinced Close Encounters would do better than his film, that he begged Spielberg to trade profit points with him on the two films. Spielberg figured, “Why not?” and he’s reportedly been collecting ever since, to the tune of more than 200 million dollars. Nice little trade there (though I’m sure Lucas isn’t losing any sleep over it. According to “Celebrity Net Worth,” he’s worth 7 billion dollars – Spielberg is at a paltry 3 billion). Close Encounters went through a lot of different iterations before it got made. Spielberg was originally going to shoot it before Jaws with only a 2.5 million dollar budget. He had UFOs landing on Robertson Boulevard, which nobody seemed to like (ironic since that’s all they want nowadays). After Jaws’s success, every studio was willing to let Spielberg make any film he wanted, but the script for “Close Encounters” still wasn’t there. The main character was a Project Blue Book agent, and then a police officer, but Spielberg said he couldn’t identify with those people. Hence, he eventually settled on an everyday normal blue collar worker for the protag. This is what finally allowed him to see the movie clearly. Though a ton of people worked on the screenplay, Spielberg ended up with sole credit.

1) If possible, the audience should identify with the hero – One of the keys to Spielberg’s mega-success is his penchant for building a story around a character everybody can identify with. Here, we have the everyday working man. And typically Spielberg uses a boy as the main character, as it’s instantly identifiable to the core audience, boys and men. I mean, who doesn’t remember the innocence and wonder associated with being a young boy?

2) Know the everyday man’s limitations – To be honest, you don’t find many movies today focusing on the everyday man in the extraordinary situation. Instead we have police officers and secret agents and former agents and former Navy Seals being placed in extraordinary situations. The reason for this is that when the action heats up, producers want your main character to be able to keep up. We have to believe that our hero can take down a military trained baddie or escape a building surrounded by the FBI. It’s hard to buy that a “normal guy” would be able to pull that off. Thus, we get “exceptional guys.” So, if you are going to write an “everyday man in an extraordinary situation,” make sure all the extraordinary stuff he does is believable and logical, which “Close Encounters” does a good job of.

3) The Teaser – The “teaser” is something that’s typically used in a TV pilot. It’s that first scene that creates a sense of mystery or wonder or suspense or shock or all of the above. “Teasers” are also often used in big splashy blockbuster-y type movies, such as Close Encounters, where we start with air traffic controllers tracking a strange blip on the radar that eventually disappears into thin air. A teaser is a great way to grab the reader’s attention immediately so it’s highly advisable if it fits your story (but please, avoid the cliché, “Cut to X weeks ago” after the teaser. It’s so overdone and should only be used if it’s absolutely essential to the story).

4) When writing a big set-piece scene, pretend that the producer nixed it because of budget. What would your replacement scene be? – The opening of Close Encounters has several planes coming in contact with a UFO. We could’ve seen this play out up in the air, but instead we see the scene exclusively through the eyes of air traffic controllers. The scene is tense and exciting for the very fact that we DON’T see what’s going on. It’s the difference between a 2 million dollar scene and a 20,000 dollar scene. And I’d argue the 20,000 dollar scene is better. You see, most big set piece scenes tend to be obvious. Cars chasing after another. Explosions. Shootouts. Space battles. We’ve seen all that stuff before. When you ask yourself to come up with the “low budget version” of a scene, you often have to be more creative, and that creativity results in something way better.

5) The second act is all about STRUGGLE – Remember that the second act boils down to your hero struggling. He should be struggling inside, outside, with the world, with the people in his life. Struggle struggle struggle. Roy Neary (Richard Dreyfuss), our hero, is struggling with this thing that he saw. He’s struggling with his wife, his kids, with what he should do. Every step of his life becomes a struggle. Struggle results in drama, and when done properly, anything dramatic will keep an audience interested.

6) Get those “marketing scenes” in there – Spielberg is a master at thinking of the marketing while writing his script. He looks for those 4-5 scenes that are going to look great in a trailer, that are going to make people HAVE TO leave their homes to drive to the theater and see his film on opening night. You get it here with the little boy being summoned by the big giant lit-up UFO outside the house. You get it with the headlights behind Roy’s truck going UP ABOVE instead of AROUND him. You see it, obviously, in Raiders of the Lost Ark with Indy running from the boulder. As “sell-out’ish” as it sounds, you need to be thinking of the marketing of your film as you’re writing it. Never let it dictate the story. But be aware of how important it is.

7) Explore your second act in your first few drafts, then streamline it for the final draft – Close Encounters actually has a very slow and wandering second act. This makes sense, as they rebooted the story several times during development. Spielberg likely threw his shooting script together with time running out. Hence this draft has a second act with a first draft feel. Tons of scenes with Roy driving around for his job, at home talking to his family, all mixed in amongst an unending amount of UFO sightings all over the world. I encourage you to use a few drafts to explore your second act. This is where you find those unexpected storylines and snazzy subplots. But at a certain point, you have to streamline: That means cutting out all the stuff that doesn’t relate directly to the protagonist’s goal – and that goal here is Roy trying to find an answer to these UFOs. If that’s not the focus of a scene, it should probably be cut.

8) A passionate main character – I believe that we, as people, are drawn to passion. Whether it be the butcher down the street who loves chopping meat for you, the musician who couldn’t imagine himself doing anything else with his life, or the blogger who wakes up every day excited to write about screenwriting. Movie characters are no different. We love to follow and root for passionate people, people who are driven by their goals and dreams. Roy becomes so passionate in his pursuit of these UFOs (who can ever forget the model mountain he builds in his own living room?) that we can’t help but root him on and hope that he achieves his goal.

9) Once the aliens show up, so what? – Another genius thing about Spielberg’s movies is he understands that once the cat’s out of the bag, the cat’s no longer interesting. He famously held the cat back with Jaws (despite it being by necessity), but does it even more so here, waiting until the very last scene to reveal the aliens. He knows that if he reveals the aliens early, that sense of mystery and intrigue and suspense is gone. It’s getting harder and harder to do this in a day and age where audiences require eye candy as soon as their butts hit the seats, but executed well, it can still work.

10) Close Encounters is a great reminder that you have to continually take chances to succeed in this business. Sci-fi was NOT popular at the time this movie was made. Hollywood thought a movie about UFOs would be stupid. People who claimed they saw UFOs in the 70s were considered to be loonies. Spielberg could’ve made anything he wanted after Jaws, but he took a chance on something he was really passionate about. I’m a firm believer that you have to take a big chance with every screenplay you write if you want to succeed. If you’re just following the latest trends, you’re not going to stand out.

The new Star Trek film underperformed. But all we at Scriptshadow care about is, “How was the writing?”

Genre: Sci-Fi

Premise: Captain Kirk and crew go after a mysterious villain who performed a terrorist attack on the Federation. After chasing him down, they learn that it’s actually someone within their own ranks that they need to worry about.

About: This is likely JJ Abrams’s last foray into Star Trek, as he’s been asked to take over the most glorious awesomest greatest franchise ever (coincidentally both mine and JJ’s favorite franchise): Star Wars. One other thing of note here: Current screenwriting whipping boy Damon Lindelof contributed to “Star Trek: Into Darkness.” That makes TWO huge summer movies he’s written (with the other being the troubled zombie flick “World War Z.”). If you want to read a great article about Lindelof and his insecurities as a writer and how he was terrified to come in and save World War Z, check out the article here.

Writer: Roberto Orci & Alex Kurtzman & Damon Lindelof

Details: 132 minutes

Where are all the Star Trek fans? I heard the studio was hoping to make 100 million dollars this weekend and only made 70. Trekkies, wuddup?? We even got to see the Klingons in this episode. And the previously established greatest Trek villain ever!

I don’t know why I’m getting all upset. I was never a Trek fan. I’m just a JJ fan, who was also not a Trek fan (I’m still confused why someone who hated a franchise would choose to direct a movie for that franchise). But I guess all I really care about is, “How was the writing?” and, “Is Trek 2 better than Trek 1?”

Unfortunately, those aren’t easy questions to answer. There was definitely something exciting about getting to see a re-imagined Star Trek the first time around. It was new. It was fresh! That freshness is gone. And some of that Star Trek luster is gone with it. On the flip side, you don’t have to spend half the screenplay setting up the world, like the first did. You can jump straight into the story. Which is what Into Darkness does. But was it successful??

Into Darkness has our Trek crew doing what it was created to do – explore new worlds. That’s THE PLAN anyway. But when Kirk finds a neophyte civilization about to be wiped out via an active volcano, he and Spock decide to save it. They barely do so, but in the process alert the civilization to their presence (a big no-no) AND almost die. This leads to Kirk being relieved of his command.

Meanwhile, a terrorist blows up a Trek archive building, (MAJOR SPOILER) who we later find out is the infamous Trek villain, Khan! Khan then jets out to the Klingon home planet, where he know he’ll be safe, since the humans and the Klingons are on the brink of war. But Kirk and crew go after him anyway, capture him, and find out the truth: that the President of Star Federation (played by the original Robocop!) is trying to kill this dude.

When Kirk won’t follow orders and kill him himself, then, Robocop comes after him, hellbent on destroying not just Khan, but everyone on Kirk’s ship as well. Kirk will have to decide who’s more dangerous here – Khan or Robocop – and stop them. All while trying to protect the thousands of crew on his ship.

99% of the time, I can get a sense whether a movie or a script is going to work within the first scene. How that scene is constructed tells me a ton. Is there drama involved? Intrigue? Suspense? Is it original? Is the scene meticulously plotted out? Or is it sloppy? If it’s sloppy, for example, that usually sets the tone for the rest of the movie. I mean, if you can’t make your very first scene clean, how can I expect you to make the following 59 scenes clean?

Into Darkness started out… wrong. It wasn’t entirely clear to me what was going on. You had Kirk running from these natives. Then we were cutting to Spock being lowered into some lava pit. For the first 60-90 seconds of the sequence, I thought Spock was on a completely different planet. I wasn’t linking him to the native stuff.

Eventually I figured it out, but if you look at a similar opening sequence, Indy going into the cave in Raiders of the Lost Ark (which clearly influenced JJ in this scene) – that’s a sequence you’re never confused by. I suppose JJ may have been doing this confusing cross-cutting on purpose? Maybe he wanted you to be be curious about how the two related to one another? But I think that’s the wrong move. Like I said – the opening scene sets the tone for the movie. It’s gotta be clear. There are instances where you want things to be confusing to establish intrigue (the layered dream sequence opening of Inception), but this wasn’t one of those times. And for this reason, I was really scared for Into Darkness.

But the script does rebound. The mystery terrorist put the story on a clear path: Find the terrorist, take him down. There were also quite a few of the mystery boxes JJ is known for. Like a) who is this terrorist? And b) what’s in these missiles that everyone seems so up-in-arms about? (Spoiler) – We eventually find out that the missiles are holding humans inside, which was a nice unexpected surprise. Although I thought for sure when the first one was revealed, as it appeared to be holding a bald guy, it was going to be Captain Jean-Luc Piccard (from the Next Generation). I had no idea how they were going to make that make sense, but it got me revved up (alas, it was not to be).

And I think that’s where JJ really excels. He keeps putting those mystery boxes out there so that you always have to find out what’s inside of them. Even when you’re not 100% into the movie, you still want to see what happens next. But I think the real feat here with the writing was how “follow-able” the writers were able to make the plot, despite how much it jumped around.

We talked about plot points a month ago, and how you want to keep changing up your story in order to keep it fresh. But (at least in my opinion) the plot point changes in Into Darkness were pretty severe, to the point where I wasn’t sure where the story was going. Or really what the main plot was. I mean first “Darkness” is about Kirk getting canned. Then he’s reinstated as a second-in-command on another ship. Then the terrorist attack happens. Then the terrorist runs away. They have to go chase the terrorist, with some foreshadowing of a potential Klingon war. But there is no Klingon war. Then the Federation President comes after them, as he’s revealed to be the bad guy. Then Khan kills the bad guy, and becomes the reinstated bad guy.

The writers do a good job keeping all of this clear, but it’s a huge gamble, as at a certain point, your reader/audience may throw up their arms and scream, “Dude! What the f*&k? is this movie about?!” When you write a script, you can write it two ways. You can establish the goal right away and spend the rest of the script showing your main character trying to obtain it. Or you can constantly keep changing the storyline and the goal, with new twists and turns dictating the narrative.

So with Raiders Of The Lost Ark, for example, we know the goal from the outset – find and bring back the Ark. Into Darkness, we’re not sure. We’re not really ever sure. And that’s what’s so dangerous about writing these types of scripts. They’re a bag of mysteries. And it takes a tremendous amount of skill to keep a story interesting that doesn’t have that constant. Whenever I see amateurs try to pull this off, it’s a guaranteed fail. They’ll keep throwing in new surprises and twists every ten pages or so, but it feels like it’s being made up as they go along. They only know how to change the variables. They don’t have an overall game plan.

I think that’s the difference when a professional takes on one of these scripts and when an amateur does. The professional outlines and makes sure it all makes sense, that there is something underneath that’ll support all these twists. Whereas the new writer will simply make up twists on the fly and believe that’s enough. At least, that’s what it feels like to me.

In the end, Into Darkness was sort of a strange, daring film, in that it did have a weird, constantly changing plot. But it found a way to make it work. The natural conflict between Kirk and Spock always kept things interesting. The “flying through debris” action sequence was really well executed. Khan was an interesting (if not exceptional) villain, who had a lot more meat to him than Eric Bana’s villain from the first film. And after a bit of a slow section following the opening scene, the script never lets up, pounding us with immediacy – an ingredient essential for any good summer popcorn film. I liked it. I mean, it wasn’t amazing, but it was solid.

Script rating:

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

Movie rating:

[ ] what the hell did I just watch?

[ ] not fit for a Klingon

[x] worth the price of admission for anywhere but the ridiculously expensive Arclight

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: If you’re a new writer, I’d suggest mastering the “Raiders Of The Lost Ark” model before you move on to the “Star Trek: Into Darkness” model. Establish a goal for your protagonist right away, then have them go after it, repeatedly running into obstacles during their pursuit. If you keep changing your character’s goal and keep rearranging the plot’s purpose the way “Into Darkness” does, you’re going to find your plot a lot harder to wrangle in. It can be done, but you need a lot of practice before you’re ready for it.

What I learned 2: I don’t know why this particular movie made me think of this, but I think IMDB should start including a section for “Contributing Writers” on each project. We know, of course, that they can’t get an official title card for the movie. But there should be a place where these writers are recognized so an internet search can bring their names up. IMDB seems like the perfect place to put this information. They’re not obligated to only include the “official” writers, and as long as it’s properly noted, I don’t see how this could do anything but help the non-top-tier writers in the business.

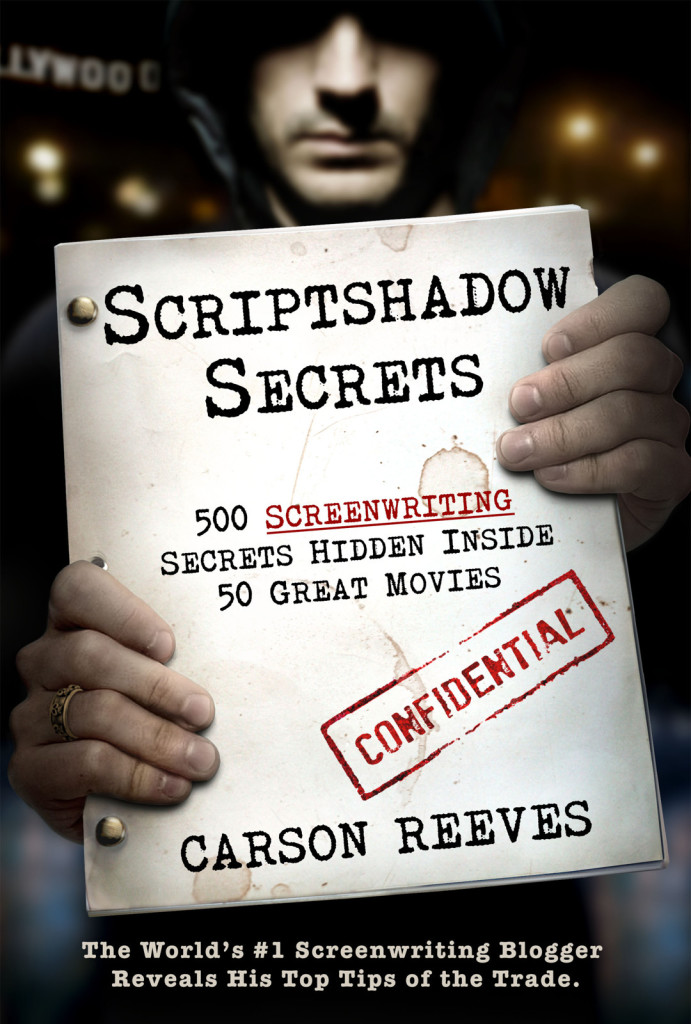

Hey guys. In celebration of, well, all of us being alive, I’m making Scriptshadow Secrets just $4.99 through the weekend! Many of you have asked when the book is coming out in hardcopy. It will, I promise. I just have to carve out some time and get it done. In the meantime, remember, you DO NOT have to have a Kindle device or an Ipad to read the book. You can download, for free, the Kindle for PC (or Mac) app, and use that to read the book right on your computer.

Get Scriptshadow Secrets for $4.99 NOW!!!

Note: Stores outside the U.S. may have a slight delay in the updated price. But it should show up soon.

This is your chance to discuss the week’s amateur scripts, offered originally in the Scriptshadow newsletter. The primary goal for this discussion is to find out which script(s) is the best candidate for a future Amateur Friday review. The secondary goal is to keep things positive in the comments with constructive criticism.

Below are the scripts up for review, along with the download links. Want to receive the scripts early? Head over to the Contact page, e-mail us, and “Opt In” to the newsletter.

Happy reading!

TITLE: Pâtisserie

GENRE: Drama

LOGLINE: A young Jewish woman in occupied France escapes the Nazis by changing places with a shop owner. But as her love grows for the other woman’s husband and child, so does her guilt.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ (from writer): My screenplay finished in the top 6% of last year’s Nicholls, perhaps you can tell me why it didn’t crack the top 5. It was also the Screenplay of the Month on both Zoetrope and TriggerStreet.

TITLE: A Call To Respond

GENRE: Action/Thriller

LOGLINE: A first responder is the target of a madman, but his greatest enemy may be the public he vows to protect.

TITLE: X-9

GENRE: Scifi/Action

LOGLINE: In a world overrun with monsters, a futuristic city thrives behind a massive wall. But when a conspiracy threatens to destroy it all, the city’s last hope rests on the shoulders of a criminal in a stolen combat suit.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ (from writer): You mean besides the guy in the armor punch fighting monsters? Well. There is some solid character work, themes dealing with duty and what makes a hero, and a few twists and turns. It’s something that Hollywood flips for: something that feels familiar but isn’t.

TITLE: The Golden House

GENRE: Period Drama

LOGLINE: A young Roman risks his life and his friendship with the emperor when he secretly pursues a woman who has sworn allegiance to the cross, a crime punishable by death.

TITLE: Drug War

GENRE: Action/Thriller

LOGLINE: A US Marine enlists the help of a Mexican journalist to rescue his father who is being held hostage by a powerful drug cartel.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ (from writer): I was a finalist in the Industry Insider Screenwriting Contest immediately following Tyler Marceca. I even had the same mentor. It wasn’t hard to accept that following Tyler’s path was a real long shot when hit by the reality of turning a solid 15 pages into my first full length script and juggling writing deadlines between the pull of work and family commitments. I learned a lot from the mentoring and script notes, but did not win. Based on the script I submitted, I knew the only way I would win is if the other scripts were not good. Seven months and several versions later, I believe it’s ready for an Amateur Friday review–comments and all.

So the other day I was sent a link to Melissa Joan Hart’s Kickstarter project page. Melissa was high on the recent successes of fellow Hollywood middle-folk Kristin Bell and Zach Braff after getting their movies funded on Kickstarter. And hey, so were the rest of us! Movie-making was finally being decided by the consumer and not some dopey producer who didn’t know the difference between Dog Day Afternoon and Beverly Hills Chihuahua. Yeah! Power to the people!

For those of you who think the internet is stupid and therefore haven’t used it this year, Kickstarter allows you to set up an online pitch, via text, video, pictures, valentine’s day cards, or whatever else you can think of, and then assign a target amount of money you’re trying to raise for your venture (in this case, a movie budget) and then let people send you money so you can try and reach that goal. Zach Braff, for example, who wrote and directed the indie mega-hit “Garden State,” has been frustratingly trying to raise the money for his new movie without giving creative freedom over to Generic Producer A-D, who would sell their left kidneys if it meant Zack casting actors like Miley Cyrus and Selena Gomez in key roles. In order to avoid those casting catastrophes, he decided to raise the money himself so he could have total creative emancipation. And he succeeded!

But here’s the thing. Zach Braff had all his cool funny friends appear on his video and for the most part, he was funny and cool, too. Melissa Joan Hart on the other hand…..? Not cool. Not funny. I mean she has her MOTHER in the pitch video with her. Rule number 1. When you’re doing a Kickstarter campaign, DO NOT INCLUDE YOUR MOTHER IN THE PITCH. You’d think that’d be obvious but I suppose the tool is new enough that people haven’t figured out all the nuances yet. For that reason, watching the Melissa video go down was sort of like watching a bad, slow-motion Gangnam Style impression. I mean here’s the logline she listed for the project, titled “Darci’s Walk Of Shame”: “An impulsive act has Darci face enormous hurdles to get back to her sister’s wedding & avoid her family witness her first walk of shame.” Umm, what does that even mean?

But it gets really bad in the “prizes” section, something Hart even promotes in her pitch video as being better than the wack prizes former successful campaigners Veronica Mars and Zach Braff promised. For $100, you get two of the cast members of Darci’s Walk Of Shame (people whose identities we don’t know yet) to follow you for ONE YEAR on Twitter. That’s right. You get two unknown struggling actors to follow you for one (AND ONLY ONE!) year on Twitter! The description of said prize makes it very clear, however, that one of those people will NOT be Melissa Joan Hart. Nope, she can’t be bothered to click a button on her Twitter feed that says “Follow.” Far too stressful. It’s no surprise that of the 2 million dollars Hart was trying to raise to make her movie, she only made 50,000.

Okay, you’re probably wondering why I’ve turned today into “Make Fun Of Melissa Joan Hart” day. Truth is, Melissa seems like a really nice girl who was a little misinformed about what kind of people and projects Kickstarter rewards, as well as how to put together a snazzy pitch. The reason I bring Melissa’s struggles up is because it got me thinking about screenwriting. Specifically how Kickstarter can help screenwriters. Now you’re probably thinking I’m going to go into this whole spiel about putting your script up on Kickstarter and trying to raise money for your movie yourself. No, I’m actually telling you to do the opposite.

You see, one of the most common complaints I hear from screenwriters is how frustrating it is to be on the outside. How producers keep rewarding these crappy screenwriters with produced credits, buying up project after project of theirs, while they’re sitting here with a much better new spec that (in their opinion) is worth a six-figure sale. Why won’t more people give them a chance? Read their stuff? Give them that money!? Why does Hollywood only play ball with their own players?

Well, let me ask you a question. Why haven’t you gone over to Kickstarter, my dear screenwriting brethren, and invested in any of these upstart movies people are putting together? I’m not talking about giving them a thousand dollars. Or even a hundred dollars. Why haven’t you given them, say, 10 bucks? I don’t read minds but I’m pretty sure your answer is something like: “Because I don’t know those people.” And for that reason, you don’t care about them or what they’re doing. I mean, who knows if they even know what they’re doing? Why would you shell out ten bucks for something so uncertain?

Ah-ha! Let that obvious stance sink in for a moment.

Now ask yourself the same question about your script, but from a producer’s point of view. Why should they read or buy your screenplay? They don’t have any inkling of whether you know what you’re doing or not. Why would they give you 2 hours of their time or 300,000 dollars of their money? You may say, “Well 2 hours is not a lot of time!” It isn’t? How long does it take before you’ve ditched one of those Kickstarter pages? 30 seconds? 20? I bet you’re not meticulously reading every little detail, going through every single prize, watching the pitch video from start to finish. Heck, chances are you made a ten second glance and you were out.

You see, with Kickstarter, we the people visiting these pages are the (potential) producers. We decide if something is worthy or isn’t. When someone like Zach Braff comes along, someone who’s proven himself by making a good movie, we’re way more likely to give him money because he’s proven he can do it. But when somebody we’ve never heard of before pitches us something, there’s no way we’re giving away our hard-earned money. We simply don’t know if this guy can pull it off.

That, my friends, is how producers are looking at you. Each individual script you write and send out there is like its own little Kickstarter campaign. And just like the Kickstarter campaigns you don’t give a shit about because you don’t know those guys, they’re doing the same. You can’t blame them because all they’re doing is what all of us do every day. We filter out the junk. We choose movies based on our familiarity with the people involved. Even if you’re one of the lucky ones and you get a producer to actually read your script and actually LIKE it, you still have no established record. So instead of going with you, the random guy, they bet on the sure thing – the previously successful book or graphic novel or video game.

Now you may think I’m trying to depress the shit out of you. As I read back through this post, it certainly sounds that way. But the truth is, the Kickstarter approach can actually help you write and market your next script. Ask yourself, what kind of Kickstarter pages (that DON’T have proven people at the helm) might get you to invest money? Probably people with a really put-together professional Kickstarter page for one, right? A clean synopsis. A well stated business plan. Someone with a really great movie idea. Someone who probably posts one of their previous short movies and it looks amazing, or they post some pre-viz work for this project that looks stunning – stuff that gives you confidence these guys are capable of making something great, right?

Well, why not take that exact same approach and apply it to the writing and selling of your current screenplay? 1) Choose an original marketable concept 2) Execute that concept 3) Write a query letter that excitedly teases your script and demonstrates your professionalism. If you fail on any of these fronts, it’s very likely you won’t sell your screenplay. So the next time you complain that Hollywood doesn’t care, hop over to Kickstarter and ask, “Why don’t I care about them?” Put yourself in those producer shoes and ask why you’re not contributing your hard-earned money to these people (i.e. the idea’s stupid, they can’t spell, they look unprofessional) and make sure you’re not making the same mistakes when you’re writing your script, pitching your script, or sending out query letters. I can’t promise this approach will end up in a sale. But I CAN promise it will give you your best possible shot at one. Good luck!