So the other day I was reading this transcribed speech from Steven Soderbergh, which he recently gave at an event. The speech was significant because Soderbergh hinted that he would be dropping some bombs on Hollywood. Soderbergh has become an interesting topic of discussion over the last year or so because he’s a successful filmmaker who’s decided to retire at a relatively young age, which NEVER happens. Hollywood decides when to spit YOU out. Not the other way around. If someone’s still giving them money, most directors direct until they die.

However, strangely enough, Soderbergh’s career has picked up to an unfathomable pace, with him directing more movies than Woody Allen. It’s almost like everyone out there wants to get him before he’s gone. I’ve heard about this guy retiring 6000 times yet he’s STILL making movies. He’s even discussing Magic Mike 2. Which leads me to believe that he’s not going to retire at all. He’ll just keep this charade going because it keeps getting him work.

However this is a man who DID say to Matt Damon awhile back, “If I have to do one more over the shoulder shot, I’ll slit my wrists,” so let’s assume he IS going to retire. This means this was sort of his “going out” speech, the one where he says fuck you to everybody who was an asshole to him during his career. Well, it wasn’t exactly that, but he did take out his frustrations on the Hollywood machine, a machine he believes has lost touch with the very art it’s trying to produce.

It all started when he saw a random guy on a plane load up a video that was two hours of ONLY action scenes. This freaked him out because it convinced him he was completely out of touch with the movie-going public. If people aren’t watching full films anymore, but only the “good parts,” then where are we headed? To a place where only Michael Bay is allowed to make films?

Here’s the thing. I know people like that guy on the plane. I have a couple of friends who watch stuff like that. I make fun of them. But they make fun of me too, calling me a film snob who would rather watch an audio commentary track than the actual film (note: this is only occasionally true). The thing is, these people are just as rare as the people I see going to artsy foreign films. They’re the extreme, not the norm. You’re just as likely to see someone pop in a rare indie film on the plane as you are someone who only watches two hours of edited action scenes.

Soderbergh goes on to say that the meetings he’s been taking are getting stranger and stranger. He keeps running into executives who don’t know anything about movies. They’re way more concerned with the business side of things. Well yeah, that’s because since the beginning of cinema, movies have been a battle between art and business. People don’t just give money away (except for on Kickstarter of course). They want some kind of return on their investment. So if you tell them you want to make a movie about a sheepherder who lives a life of solitude called “Solo Sheepherder,” they’re going to ask you if you can include a girl, no matter how “stupid” that sounds since “solo” is in the title. It’s the nature of the business.

Soderbergh even went so far as to say if he were running a studio, he wouldn’t have all these restrictions on directors. He’d just find talented filmmakers and let them make whatever they wanted. He even used Shane Carruth as an example. I think this exemplifies how off the mark Soderbergh is in this speech. You’re going to give people who make movies about psychic pig people money to do whatever they want? You’ll be broke within six months.

As much as it sucks, movies are a collaborative effort. Too many people are required for them not to be. This means you’ll ALWAYS have to deal with other humans. True, sometimes you’re going to run into idiots. But is that any different than if you were working at Wal-Mart, Facebook, or Pink’s Hot Dogs? I’ve found that idiots are everywhere. So of course you’re going to get them in the movie business.

All you can do is try and understand their perspective and work through it. You might be upset that they only see two movies a year. But so does the average American. Which gives them a perspective you don’t have. They want that extra explosion scene because the person coming to that theater never sees explosions. They’re not like you or me, film nerds, who have seen every movie known to man and therefore see 20 explosions a week. Maybe giving them a little more of that could be a good thing. Your job, then, is to figure out how to make it work inside your specific story.

I mean yeah, it sucks that not everyone has free reign to do whatever they want. But that approach hasn’t exactly proven successful either. I mean take Soderbergh’s Bubble, where he had 100% creative freedom. I dare you to watch that movie without being bored out of your mind. Or Upstream Color, a nonsensical badly written film about psychic pig people. No, that’s not a good thing. Or look at the granddaddy of indie film, George Lucas, who had 100% creative freedom to do whatever he wanted with his Star Wars prequels. How did those stories turn out?

I think part of the problem here is that Soderbergh has always been an insider/outsider. He’s an indie guy first who struggled mightily after his breakthrough film, Sex Lies and Videotape, making strange movies with no commercial appeal like the black and white “Kafka.” Because Hollywood rejected him after those films, he came back to it with only one foot in. And I think everyone who deals with him approaches him with that information. Executives are going to treat him differently than a guy like David Fincher because they know what kind of movie David Fincher is going to make. With Soderbergh, you don’t know if you’re going to get Ocean’s 11 or Bubble 2.

So I think Soderbergh is telling this side of the story from a very unique perspective, from a guy who’s in an industry he’s never completely been comfortable in or understood. For example, another part of his speech was how he couldn’t figure out why his most recent movie, Side Effects, didn’t do well. It was a thriller. It had two young stars. Why the heck didn’t it pull in better numbers? Well to me, the reason it didn’t do well was obvious. Every ad and trailer I saw showed a dark indie “smart” thriller.

Tell me the last time a dark indie smart thriller made a lot of money at the box office. They don’t. Contrast that to, say, Halle Berry’s latest movie, The Call, which did way better than expected at the box office. People went to that movie because it was a clear thriller. No pretense. No artsy undertones. It knew it was a thriller so people knew they’d get thrilled.

I’m not saying there’s any right or wrong here. I really liked Side Effects and although I haven’t seen The Call, I’m pretty sure I’d dislike it. But if I remove the screenplay enthusiast and cinema lover in me and place my producer hat on, which one of these films would I make? Probably The Call. That’s the one that keeps my production company open. That’s the one that allows me to make more movies.

Of course, I’d hope that it wouldn’t come down to just those two movies. My ambition in life is not to make movies like The Call. One of the points Soderbergh skips over, here, is the potential for a happy medium. Money guys never get exactly what they want. Filmmakers never get exactly what they want. But you work hard enough and learn enough about the craft so that, hopefully, you can make both sides relatively happy. If someone wants an action scene in your drama, sit down and see if you can use the note to your advantage. Sometimes the best ideas come from the most nonsensical suggestions. If there’s one thing I’ve learned about screenwriting, it’s that if you only do what you want to do, your scripts tend to be boring. Being pushed outside your comfort zone forces you to explore new areas, which leads to new ideas, which often leads to a more interesting screenplay.

I think what bothers me most about Soderbergh’s speech is that it spreads this message that Hollywood is this evil hopeless business where it’s impossible to do what you want to do, even if you’re one of the top directors in the world. But I’m a firm believer that life is what you make of it. If you tell yourself everyone’s a moron who doesn’t see how good your product is, you attract morons who don’t see how good your product is.

And I believe the same thing applies to screenwriting. If you think Hollywood is run by nepotism and it’s impossible to get your script read or sold, then you’re never going to get your script read or sold. Why? Because you’ve convinced yourself it’s impossible, and therefore stop trying. If you believe it IS possible, you’ll explore every single avenue until you find a way in because you KNOW it’s achievable and therefore won’t quit until it happens. With the rare exception, these are the people who I see breaking in the most. They work hard and never stop believing. Which is exactly what you guys should be doing. Hollywood is not an evil place. It’s what you make of it. Never forget that!

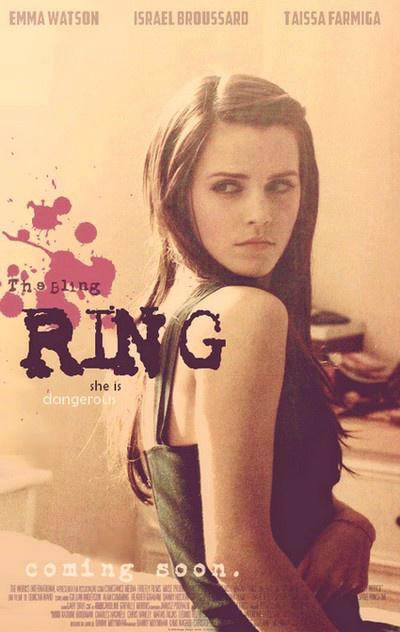

Sofia Coppola goes back to her roots with her latest film. Will it reignite her career?

Genre: Drama (based on a true story)

Premise: A group of Los Angeles teenagers start robbing high profile celebrity homes, stealing thousands of dollars’ worth of merchandise.

About: This is the newest feature film from director Sofia Coppola. Coppola rose to fame with her 2003 film, “Lost In Translation,” but has since had trouble recapturing the indie audience (her last film, “Somewhere,” made $120,000 at the box office). This may have spurred her to do something more marketable, which a film about rebellious teens would definitely qualify as. It’s important to note that Coppola is a director first and a writer second, so some of the pieces here could end up feeling different once on screen. The film is currently playing the festival circuit and stars Emma Watson.

Writer: Sofia Coppola

Details: 82 pages (Oct. 6, 2011 draft)

The script for The Bling Ring starts out with a quote from Nicole Ritchie: “Life is crazy and unpredictable, my bangs are going to the left today.” This quote is meant to prepare us for the script, an ode to the absurdity that drives the average D-List celebrity’s life. But also to highlight our obsession with these faux celebrities, no matter how mundane or ridiculous their lives may be.

In a world where young women are now making sex tapes to pocket a small fortune and stay in the spotlight, I suppose there’s a statement to be made here. But that’s assuming the author can find an interesting angle into the story, an angle they can dramatize in order to keep people entertained for 90 minutes.

Sofia Coppola is not that author. She kind of cheats when she makes movies. She places the camera on a couple of (usually) blank characters, adds some great cinematography and a kick-ass soundtrack, then edits it together like one long music video. While some may argue that this is a legitimate way to make films, I think she uses it as a crutch. When you hide behind your music and your edits, you don’t have to face your story. And the story here is about as boring as they come. I mean, nothing happens except the same boring thing over and over again.

I liked Lost In Translation. I thought it was her most accomplished film. She took a relatable situation (fish out of water) and added two characters who we felt sympathy for. She’s never done anything like that before or since. There’s rarely anyone to root for in her movies, and I’m not sure if she does that on purpose or if she simply isn’t aware that by creating unsympathetic characters, she’s alienating her audience.

Anyway, The Bling Ring is a true story centering around a Korean-American teenager named Rebecca (who is clearly the Caucasian Emma Watson in the film) and her new, outcast gay friend, Marc. The two find themselves at some sort of Los Angeles “reject” school for being disobedient little brats at their previous “normal” schools. It’s hard to tell if these two are really well off, sort of well off, or just well off. But they seem to have some kind of money.

Which makes it strange when Rebecca becomes obsessed with breaking into Beverly Hills houses while the owners are gone. It starts with anyone she’s found out is out of town, but then moves to celebrity houses, like Paris Hilton, Audriana Partridge, and Lindsay Lohan. Her, Marc, and her other thuggish rich friends watch TV to see when these stars are out of town, then go to their houses and break in. And because the stars live in such nice areas, they never lock their doors.

But they don’t just go in the houses, they start stealing stuff like luggage and jewelry and cash. Rebecca’s the ring leader – cool, calm and collected all the time – and Marc’s the worrywart, always freaking out about getting caught.

Eventually, the burglaries are reported, and TMZ starts covering them. Instead of scaring these teenaged terrorists, it only helps grow their popularity. They become cool and hip among their friends, something that doesn’t seem like a big deal since their friends already thought they were cool and hip in the first place. So I guess they’re just slightly cooler and hipper.

Anyway, Marc ends up getting identified in one of the surveillance videos, then rats out all the other players to the police. All of this happens in the most undramatic way possible. We never see anyone confront anyone else after this ratting out. That would actually be interesting. Instead it all sorta happens casually. A court date is then set, and a few months later they find themselves all going to jail. The end.

Oh man.

Please help me God with these indie writer-directors who don’t know how to write. I’m not going to say this is as bad it gets, but it’s close. I mean, first of all, why the heck did anyone think this would be a good movie? It’s about a bunch of sorta spoiled kids who rob a bunch of really spoiled celebrities.

NOBODY is likable here, with the exception of maybe Marc. But because he’s so bland, we don’t have an opinion on him either way. So we’re neutral on the “hero” and hate everyone else. That’s a recipe for script disaster.

The next problem – there’s no plot! None. I’m not going to pretend I’m surprised. Sofia Coppola isn’t exactly Miss Plot. But there’s a certain level of drama expected with every movie, twists and surprises that make you curious and keen to keep watching. There’s none of that here. Much like her previous two movies, The Bling Ring is obnoxiously repetitive.

Go break into a house. Marc freaks out, says they should leave. Rebecca says chill out and they stay longer. A few pages later, they go to the NEXT house. Marc freaks out, says they should leave. Rebecca says chill out and they stay longer. This exact same situation is repeated no less than seven times!!! There is nothing different about any of the break-ins!!!

Stack on to that boring characters and boring relationships, and you have one hell of a boring screenplay. I mean at least inject your main relationship with a little drama, a little conflict. Rebecca and Marc never share a harsh word with one another. Rebecca says let’s go do this. Marc says fine. Besides the occasional whining from Marc about wanting to leave, their relationship can be boiled down to the above paragraph. There is literally NO DRAMA and NO PLOT and NO CONFLICT in this movie.

The thing that bothers me about Coppola is that she wants to make these movies about life – shine a spotlight on the world’s problems. But her perspective is all warped. She sees the world through the eyes of a privileged woman who grew up in a Hollywood super-director’s home. Even if she rebels against that, it doesn’t change the fact that none of us can relate to what it’s like to be a teenage girl running around Hollywood doing blow at semi-famous people’s houses. That’s ALL she writes about, is famous or once famous people being miserable.

Her straying from that is why I liked Lost In Translation. We could relate to those characters. They both felt out of place and lost in life. Not to mention it was the only time Coppolla created characters we actually cared about. Having Scarlett Johansen’s character get screwed over by her asshole husband endeared us to her, made us root for her. I don’t see any of that here. We just don’t like or care about anyone. Characters we don’t like in a script with no story? I don’t care if you’re the best filmmaker in the world, if you add the greatest cinematography and the world’s best soundtrack – the movie’s screwed.

If there’s any chance of this working, it will hinge on the teenage girl crowd. There’s a theme of rebellion here that a younger crowd will gravitate towards. But I will stand behind my belief that a thematic connection is not enough to satisfy an audience. A story that pulls you in and makes you care about the people involved is required. And sadly, there’s none of that here.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me (by the skin of its teeth)

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: The Likability Leash – Look, no one says your hero(es) needs to be extremely likable. But each hero you write has a “likability leash.” And the further you extend that leash, the less likable your character becomes, and the more of a chance your audience turns on that character. Since it’s almost impossible to write a good movie where we aren’t rooting for the main character, you best keep that likability leash fairly close.

What I learned 2: If you don’t have conflict in your logline (and therefore your screenplay), you probably have a boring screenplay. Remember, movies are about conflict. You never write the logline, “Joe breaks up with his girlfriend and she’s cool with it.” You write, “Joe tries to break up with his girlfriend, who threatens to kill him if he does.” I mean read the logline (which I admittedly wrote) for The Bling Ring: “A group of Los Angeles teenagers start robbing high profile celebrity homes, stealing thousands of dollars worth of merchandise.” There’s no conflict! No “but”! That’s why this story is so boring. There’s no opposing force.

He can stop bullets. Just not bad writing.

He can stop bullets. Just not bad writing.

I still remember going to see The Matrix Reloaded. My friends and I had bought tickets for a prime-time Friday showing, but Thursday night I couldn’t contain myself. I knew there were going to be midnight showings at the theater right down the street, so I went to see the movie BY MYSELF. I have never had a more pathetic and sad moviegoing experience in my life. Not only was I by myself in a theater packed with people, but I couldn’t figure out what the hell I was watching. What had happened to The Matrix!!?? Where was all the fun? Why were there endless passages of nothing happening? Why were Neo and Trinity the most annoying couple in the world? Why was there more dialogue than a Woody Allen film? What was the plot of the movie?? To be honest, this was the easiest movie yet to find ten “screenwriting mistakes to avoid” from. They melted off the screen like butter. But it’s still so sad. Matrix Reloaded was one of the most anticipated films in the history of Hollywood. And it failed on just about every level.

1) JESUS CHRIST! STOP USING SO MUCH DIALOGUE – The Matrix Reloaded sunk under all its dialogue. Certain dialogue scenes (with Agent Smith, with the Oracle, with the Merovingian, with the Governor of Zion, and let’s face it – with just about everyone) went on for 5-10 minutes! I don’t care HOW good your dialogue is. Unless it is ripe with conflict, unless there is some impending doom, unless it is thick with dramatic irony or shocking revelations, it will start to bore us to pieces after the first couple of minutes. The Matrix Reloaded made one of the most obvious mistakes in screenwriting – the writers wrote dialogue for dialogue’s sake. Always remember that the average scene is 2 minutes long (so 2 pages). If you’re going to go over that, make sure it is absolutely necessary.

2) Know what kind of movie you’re writing – Know what movie you’re writing, and make sure you’re giving your audience that kind of movie. So if you’re writing an action sci-fi script, don’t drown your script in dialogue. If you’re writing a comedy, don’t write a lot of dramatic scenes. If you’re writing a thriller, don’t have your characters sitting around a lot. Audiences have a certain expectation when they go to a movie. If you stray too far from that expectation, they will turn on you.

3) Make your fights matter – One of the reasons why the first Matrix was so good was that every fight mattered, every battle had stakes attached to it. We knew that if our characters lost, something terrible would happen to them (or worse – to the world). Here, we have fights just to have fights. Take the first fight in the movie, where the “new” agents crash the Morpheus’s meeting with all the other ship captains. Neo fights the three agents and we don’t get ANY sense that there’s any danger at all. Neo is going to win. And even if he doesn’t, there’s nothing these three agents could do to 40 highly trained “freed” humans. So it’s boring. Always make sure there are stakes attached to your battles!

4) Simplicity almost always trumps excess – We see it time and time again. A small first film, and after its success, a huge no-expenses-spared sequel. Yet even though the story is more grandiose, the effects are better, and the set pieces are bigger, the movie’s not nearly as good. This is because, usually, when you try to do too much – when you have no limitations – you get lost. Most of the best stories have simple through-lines that are easy to follow. So just beware of trying to make this big sprawling epic-like sci-fi film. You’re probably best going with something simpler and easier to follow.

5) Beware of “dilly-dally” scenes – As I’ve always told you, you want to jump into your story right away. And technically, Matrix Reloaded does just that. They establish within the first ten minutes that the “machines” are charging towards Zion and they need to act. However then we get a pointless fight scene with Neo and the new agents, Neo and Trinity talking about nothing, Morpheus and Dreadlocks Dude chatting about belief or something, an 8 freaking minute landing scene, our characters walking through Zion, numerous characters having pointless conversations in Zion, etc. These are all dilly-dally scenes. No story is really being advanced, so they kill the story’s momentum. Cut out the dilly-dallying and get to the scenes that actually move the story forward, dammit!

6) Comic-relief characters must be organic to the story – There’s nothing I hate more than a character who shows up telling the world, “I’M THE COMIC RELIEF CHARACTER IN THE MOVIE!” As was the case with “Kid,” the character who barrels up to Neo and Trinity when they arrive in Zion, begging Neo to let him take his bags in a comically eager manner. As with any character you write, they should emerge from the story organically, instead of being decided upon as “that kind of character,” then forced into the movie like a square peg in a round hole. This was one of the big reasons “Jar Jar Binks” was so disliked in the Star Wars prequels. He screamed “Here I am! The comic relief guy!” as opposed to coming upon the story in a natural way. Look at C3PO and R2-D2 from Star Wars. Their comic relief comes very specifically from the story, as R2 is determined to deliver his message, and C3PO is wary if all the fuss is worth it.

7) Use an intriguing mystery to get us through your setup – No matter which way you spin it, the first act requires you to set up characters and plot, which can be tough to keep entertaining. By providing the audience with an intriguing mystery, it makes this setup move along a lot faster, as we’re eager to find out the answer to this mystery. That’s why The Matrix was so awesome. We had to know, “What is the Matrix??” One of the reasons Matrix Reloaded is so boring is because there is no mystery in that first act. It’s pure setup (and poorly written setup at that). We get bored quickly. And if a reader is bored within the first act, you have little chance of getting them back.

8) Addition By Subtraction – Matrix Reloaded is a classic case of having way too many characters. When you have too many characters, the audience’s focus is spread too thin. They begin to have trouble remembering what each character is after, which can be a script killer if that happens with the main character. And guess what? That’s exactly what happens in Matrix Reloaded. Because we have to keep track of so many people, we forget what Neo’s doing, which makes most of Matrix Reloaded confusing.

9) Break into Act 2 should happen on page 25 – The moment where your hero officially sets off on his journey should happen on or very near page 25. I don’t usually use ultra-specific page references when breaking down structure, but I believe in this one because whenever I see it broken (as it is here – our characters don’t actually go out into the world and start doing things until page 40) I start to get antsy. We come into a story wanting to see a hero go after something. The longer that’s delayed, the more bored we get. Of course, this rule can be broken if there are lots of intriguing mysteries in that first act, lots of conflict, or lots of strong scenes. Unfortunately, The Matrix Reloaded has none of that.

10) Plot points over action scenes – When writers feel their script is slowing down, they often insert an action or set-piece scene to “pick things up.” The thing is, these scenes always feel empty, because you’re inserting them into the story for the wrong reason. That’s why the infamous “Burly Brawl” scene, where Neo fights 200 Agent Smiths is so boring, because we don’t know what the point of it is. It literally feels like someone said, “We need an action scene here.” Instead, if you feel like your script is slowing down, insert a plot point, something that changes the story and throws it in a slightly different direction. For example, in the original Matrix, Cipher (a member of the good guys) secretly teams up with the bad guys. This is often a more exciting way to engage the audience.

BONUS TIP – Combine a plot point WITH a set-piece – Who says you can’t do two in one? Since the studio folks love big set-piece scenes, you might feel the pressure of adding them inorganically, despite the advice I just gave. Well, why not combine your set-piece scene with a plot point? For example, in the original Matrix, a plot point that occurs when they go see the Oracle is that, surprise, the Agents are waiting for them. A battle/chase (set-piece) ensues. This way you end up killing two birds with one stone.

One of the best screenwriters ever tries to recapture the magic from one of his earlier children’s movies. Does he succeed?

Genre: Superhero/Children’s/Family

Premise: An 11 year old boy meets a man who gives him the power to turn into a superhero.

About: This was written by William Goldman, he who wrote “Butch Cassidy and The Sundance Kid,” “Misery,” “The Princess Bride,” “All The President’s Men,” and some would even say “Good Will Hunting.” For those who have just started in this career and find yourself struggling, it should be noted that Goldman received horrible grades in his first creative writing class in college. He was also an editor at the college newspaper, and used to anonymously submit his short stories in hopes of being published in the newspaper. He then had to stand by and listen to his co-workers talk about how shitty his stories were. That’s how you earn some thick skin! Later, he would research Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid for eight years before writing the script and earning a then record $400,000 paycheck for it. Break out the inflation calculator and you’ll see that translates to a 2.7 million dollar sale in today’s money.

Writer: William Goldman

Details: 141 pages (September 15, 2003 draft)

When I think of superhero scripts I want to read, Shazam is not at the top of my list. I don’t even know what a Shazam is. All I know is that when compared to names like “Batman” and “Iron Man,” it sounds a little… antiquated. It’s kind of like naming your superhero “Wowzow” or “Bizzbop.” How do you compete in a superhero dominated marketplace with a name like that?

However, what I DO want to read is a William Goldman screenplay. The guy is one of the best of all time and understands screenwriting on a primal level. I mean, Misery and The Princess Bride are two of the best screenplays ever in my opinion. True, Shazam was just a job for him. It wasn’t a project he was passionate about, like Princess Bride. But it’s still a William Goldman script. And that alone is reason enough to take a look.

11 year-old Billy Batson is an orphan, an orphan who actually ENJOYS being an orphan. That’s because his uber-hot partner in crime, 15 year old Jenny Richee, is a fellow orphan. The two enjoy each other’s company so much that whenever they’re up for adoption, they do everything in their power to make their potential parents hate them (farting being a go-to tactic – yes, I’m afraid it’s that kind of movie).

So one day, Billy is hanging out in the yard when he’s approached by a strange man who tells him to come with him. Billy obliges for some reason, and the strange man brings him to an underground cave (oh boy, this isn’t sounding good) where an old fogey with a big white beard named “Shazam” tells him that he’s been chosen to become a superhero, a dude named “Captain Marvel.” From now on, whenever Billy’s in trouble, just yell out “Shazam” and he turns into, basically, Superman (I can only imagine how this message would go over with parents – “Follow a stranger: become a superhero!”).

The only catch is that Billy must learn how to fight evil, something he doesn’t know a whole lot about. So he enlists his buddy, Jenny, to help him out. In the meantime, across town, there’s this really scary dude named Sivana whose superpower, I believe, is that he can’t die. Anyway, while I never really saw him perform any magnificent powers himself, he’s supposedly a very feared man. He also has some history with Shazam, which makes him want to kill Billy!

Eventually, Sivana kidnaps Jenny, forcing Billy to become Captain Marvel and save her. I don’t think I’m spoiling anything here by saying he succeeds. The End.

Tone tone tone. Tone is so important. It’s important that your reader understand what kind of movie you’re writing. This script starts out pretty dark, with a prison warden trying to choke a prisoner who’s already dead. We then cut to little boy Billy, who’s farting and burping at his potential parents. I was a little confused for awhile by this sharp contrast, until I finally realized this was a straight kids movie. We’re talking Spy Kids level. Which is fine. But I was frustrated that it took me so long to figure this out, and I believe that’s the writer’s fault.

Now while I loved Goldman’s writing (the guy knows how to make a script move. Go find one of his scripts. Your eyes FLY down the page), this script was so boring! Like, unbelievably boring. Goldman, of all people, should know that the number one rule of screenwriting is: Make something happen. NOTHING freaking happens in this script. Billy is still testing out his powers and learning how to be super on – get this – PAGE 80-FREAKING-4!

Neither our hero or our villain have done anything of significance for over 80 pages. It’s crazy. Where’s the story here! I mean, this is the problem with origin stories in general. You gotta have to establish the hero in his everyday life, then have him get powers, then have him learn those powers. But if you think an audience is going to patiently wait 90 minutes to get through all this – YOU’RE CRAZY!

The problems in this script can be boiled down to that. Nothing interesting happens for forever. The other day we were talking about plot points and making sure something of significance happens every 8 pages or so. I think at one point 60 pages had gone by without a single significant plot point. I’m not so much upset as I am baffled. If you look at The Princess Bride (or even Misery), you see the plot constantly changing and evolving. It’s the very definition of “making things happen.” So you know Goldman knows how to do it. Why he chose not to here, and instead made this one drawn-out story of kids talking…I mean it’s beyond me.

Crippling the story even more is the fact that there’s nothing here we haven’t seen before. If you’re going to throw your hat into a genre, you want to make sure that you’re bringing something different to the table. We’ve seen this origin thing, this “learn your powers thing,” a billion times already. And there’s also nothing special about Captain Marvel himself. He flies. He’s strong. He’s basically Superman. But because he’s not really Superman, we see him as a second rate version of Superman.

I suppose you could make the argument that we haven’t seen a movie about a little boy who turns into a superhero. And I guess that’s true. But if that’s going to be your one trademark, do something with it. Don’t have your 11 year old hero hanging around shooting the shit for 90 minutes, talking about his powers and how he doesn’t know how to be a superhero yet.

On top of this, there are a lot of really cliché choices. For example, in order for Sivana to take down Captain Marvel, he kidnaps Jenny. (sigh) I mean, we’ve seen this choice soooo many times before. And I’m sure we’ll see it again, and it may even be enjoyable. But what bothered me about this version was that it wasn’t organic to the story at all. It was literally like, “I need Captain Marvel. I shall now kidnap his girlfriend!” Nobody’s even DOING anything. They’re all sitting around in rooms or lairs while they’re deciding this stuff. That’s what bothered me so much. NOTHING WAS FREAKING HAPPENING. There was no master plot for the bad guy. The good guy did a lot more talking than doing. People are literally sitting around for ¾ of this movie. It’s baffling to me that Goldman wrote this. Nothing happens!

Luckily, Goldman remains scarily readable during this bore-fest. It’s kind of fascinating to behold. I mean his prose is just so sparse and flows so smoothly, it made a bad reading experience almost enjoyable. But, yeah, if they’re ever going to make this movie, they need to rewrite this script so it moves a lot faster and a LOT more happens. Read my plot point article. That alone will improve the script by 50%. I guarantee it!

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: I recently watched this comedian do stand-up who wasn’t getting a lot of laughs. So he turned to the audience and said: “Laugh! This shit is funny!” Well, if you were funny, you wouldn’t need to tell people to laugh. The same approach should be applied to your writing. Don’t tell people how to feel. MAKE them feel. As awesome as Goldman’s writing is, there are a number of times in the script where he says something like, “We are about to see something so much worse we will never be able to forget it.” I don’t agree with this kind of writing. Just WRITE THE THING we’ll never be able to forget. We’ll decide if it’s unforgettable. Especially because, in this specific case, it was something I’d already seen before (a cockroach crawling out of a dead man’s mouth). Therefore, it wasn’t that unforgettable at all, which made me sort of mad at the author for telling me I was about to see something amazing, only for that not to be the case.

This is your chance to discuss the week’s amateur scripts, offered originally in the Scriptshadow newsletter. The primary goal for this discussion is to find out which script(s) is the best candidate for a future Amateur Friday review. The secondary goal is to keep things positive in the comments with constructive criticism.

Below are the scripts up for review, along with the download links. Want to receive the scripts early? Head over to the Contact page, e-mail us, and “Opt In” to the newsletter.

Happy reading!

TITLE: My Asian Buddy

GENRE: Comedy

LOGLINE: A middle management loser befriends the new guy at work and changes his image.

TITLE: Observation Car

GENRE: Sci-Fi / Suspense-Thriller

LOGLINE: After witnessing UFOs and other strange phenomena, an insomniac on a cross country train trip suspects an alien invasion is underway, beginning with his fellow passengers, but when no one believes him, he must team with a fugitive stowaway to unravel the sinister agenda.

TITLE: The Express

GENRE: Thriller

LOGLINE: On the eve of World War Two, a reporter traveling aboard the Orient Express must solve a seemingly impossible crime, the kidnapping of a diplomat who has has somehow been made to magically vanish from the speeding train.

TITLE: In the West

GENRE: Horror/ Action Horror/ Period

LOGLINE: In 1704 a squad of English Rangers is sent on a mission to assassinate a French Officer, only to discover something evil in the uncharted wilderness of the New World.

TITLE: B & E

GENRE: Dark Comedy

LOGLINE:Two brothers in need of quick cash to pay off their mothers house, decide to pull a classic B & E on their rich, but arrogant, piece of shit step dad.