So a few weeks back I was reading this amateur script and it came to my attention that I was bored. The source of my boredom was that pages upon pages were going by and not much was happening. This, I realized, could be construed as the definition of screen-reading boredom: NOTHING INTERESTING IS HAPPENING. If nothing interesting happens for too long, the reader either physically checks out (closes the script) or mentally checks out (starts skimming).

However, as I kept reading, it occurred to me that there WERE interesting moments in the script. They were just few and far between. It took forever to get to them. Hmmm, I thought. If only these moments could happen closer together, I wouldn’t be so bored. And that’s how I had my “Ah-ha” moment. These “interesting moments” were plot points. The reason I was bored, then, was that there weren’t enough of them.

Clearly, then, frequency of plot points has an effect on a story’s entertainment level. The more of them you have (within reason), the more likely your story is to remain entertaining. But how many plot points do you want in your script? And how many is too little? Well, before we get to that, we should come up with a definition for “plot point.” And in order to do that, we should probably look at some examples of plot points in movies. Here are a few prominent ones.

a) The emergence of a goal (Indiana must go find the Ark).

b) A shocking twist (Cole tells Malcom he can “see dead people”).

c) An upping of the stakes (they realize in Inception that if they die in the dream, they could be stuck in it forever).

d) A mystery is presented (Why is there a naked Chinese man in their trunk in The Hangover?)

e) A key character is introduced (Sgt Powell – the cop – shows up to help McClane in Die Hard).

f) A key character is killed (spoiler – Schultz is killed in Django Unchained).

g) An unplanned interruption of the hero’s life (Neo gets an urgent phone call from Morpheus at work).

h) The emergence of a threat (after the plane crash, the wolves start stalking our characters in The Grey).

Looking over these examples, I’d say that a plot point is any real significant CHANGE in the story from what’s currently going on. It could even be simplified down to one word: CHANGE. Whenever something happens that’s CHANGING the course of the narrative, you’re introducing a plot point.

Now, of course, plot points aren’t the only things that keep a story interesting. There’s character development, conflict, sharp dialogue, suspense. Still, a story’s success often comes down to how well it’s plotted, which brings us back to our earlier question: how many plot points should there be in a script?

That’s a good question. I don’t know the answer because I’ve never sat down and physically counted plot points during a movie (although since I’m writing an article about plot points, I probably should have at some point). But hey, that’s the fun part about running a blog. When you don’t know something, you write an article about it and figure it out. Let’s take a look at one of the best plotted movies of all time: Star Wars. There isn’t an ounce of fat in this plot, so let’s see if we can locate all the plot points, add them up, and give ourselves a plot point template for our own script.

1) The opening scene in Star Wars is technically a plot point because there’s an unplanned interruption. The rebels’ ship is captured by the Empire. Now as far as I’m concerned, every script should start with a plot point because you want to jump into your story right away. So the “opening plot point” should be a given. 2) R2-D2 and C3-PO escape the ship with the stolen Death Star plans. This is a HUGE plot point as it sets in motion the entire story, which is the Empire chasing Luke, the droids, Obi-Wan, and Han to get the plans back.

3) The introduction of Luke Skywalker. Now normally, you’d introduce your main character right away, so this is sort of an odd placement for this plot point. But it turns out to be another big one because…well because it’s our main character. Which keeps us engaged.

4) The droids are captured by the Jawas – This is a smaller but still important plot point as it changes the direction of the droids’ fortune.

5) Luke’s family buys the droids. This is sort of a unique plot point in that it merges two storylines, Luke’s and the droids. But it’s clearly a major one, since now the Empire isn’t just after the droids, they’re after Luke.

6) R2-D2 runs away. With R2 running away to find Obi-Wan, it forces Luke to act, changing the direction of the story.

7) The introduction of Obi-Wan. Introducing a character is always going to change the story in some way, but don’t just introduce someone to check a plot point off your list. Make sure they’re interesting and necessary to the story.

8) Luke’s aunt and Uncle are killed. This is another huge plot point as it motivates Luke to join Obi-Wan on his trip to Alderran.

9) The introduction of Han Solo.

10) The escape from Tantooine.

11) The Death Star blows up Princess Leah’s planet.

12) Han, Luke, the droids and Obi-Wan are captured by The Death Star.

13) Han, Luke, and Obi-Wan decide to go rescue the princess (who they find out is in the Death Star with them).

14) They successfully find the princess and get her out of her cell.

15) It’s debatable whether the trash compactor scene is a plot point but I’d argue it is, since it’s an unexpected set-back to their goal of escaping.

16) The group narrowly escapes the Death Star, and Obi-Wan is killed.

17) By dissecting the Death Star Plans, the Rebels find a way to attack and possibly destroy it.

Whoa! I did not expect there to be that many plot points. I thought there’d be about 8. Since there are roughly double that, in a 120 page screenplay, you’re instituting a plot point once every 7 and a half pages (and that ratio gets even tighter if you’re keeping your script close to that magical 110 page count). However, the more I think about it, the more it makes sense. 8 pages is 8 minutes of screen time and 8 minutes is forever in the movie theater. It’s about the amount of time an audience will put up with before they need another big “moment” that changes things. So in retrospect, that number feels just about right.

I also noticed a few other things here. First, there seems to be power in “doubling up” your plot points. Vader’s introduction would’ve been a plot point on its own. But since he’s introduced during another plot point (the Empire’s takeover of the Rebel ship), is has even more impact. We see the same thing when our heroes escape the Death Star, as Obi-Wan is killed in the process. An escape is exciting. But to add a death on top of that – it’s super impactful. So double up on those plot-points where you can boys and girls!

Another thing I noticed was how important it is to mix your plot points up. In Star Wars we have interruptions, surprises, mysteries, deaths, goals, unexpected character intros, raising the stakes. You need that variety to keep your story fresh. If you’re only introducing, say, mysteries for your plot points, your story’s going to start to feel repetitive and predictable. So mix it up!

It’s also important to note that not every movie is Star Wars. In other words, not every movie is a summer blockbuster where a lightning fast pace is required. Sometimes you’ll be writing a drama or a Western or a slow-burning horror flick. And these movies require a slower pace. If you’re going to dial back the flashy plot points, though, make sure you’re really good at those other things I mentioned (character development, suspense, dialogue, etc.) because you’re asking your reader to be more patient with you. And a reader only makes that deal if you give them something in return. Character development and strong dialogue are two of a number of variables that will be expected in that deal. Also keep in mind, even “slow” movies have more plot points than you think. You might not have all these whiz-bang “summer movie” plot points popping up every 8 pages. But you should still have SOMETHING happening. For example, instead of your hero’s father being massacred by the villain, you may offer a more cerebral plot point (a character realizes that someone he trusts has been lying to him their entire relationship). So SOMETHING should still be happening.

Also remember that your plot points are only as effective as a) how clever they are b) how original they are, and c) how clear they are. If you’re just throwing a bunch of plot points on the page for the sake of having plot points, we’re going to get bored. Or if you’re throwing in derivative boring cliché plot points, we’re going to get bored. You still have to come up with interesting plot points, just like you have to come up with interesting characters and scenes and dialogue. Also, your plot points need to be CLEAR. I occasionally read a script with a ton of plot points – tons happening – yet all the activity leaves me lost. Ultimately, I realize that it isn’t that there’s too much going on. It’s that the plot points themselves are confusing or vague. Plot points are pointless unless we understand their impact on the story.

Finally, I understand that plot points can be a little confusing. My definition of them is by no means perfect, and encompasses a lot of different scenarios. So if you’re confused by this article, I’ll give you the Redneck version of plot points: “Make interesting shit happen every 8 pages or so.” If you can do that, your story should be entertaining. Good luck!

Can Ronnie Rocket out-nonsense the king of nonsense, Upstream Color?? Side note: Both scripts contain pigs!

Genre: Surrealist

Premise: (described by Lynch himself) About a three foot tall man with physical problems and…60 cycle alternating current electricity.

About: Ronnie Rocket is a script that David Lynch has been trying to make forever. Typical of many Lynch projects, it’s always had a hard time getting funding. When one of the targeted studios asked what the script was about, Lynch replied, “electricity and a 3-foot guy with red hair.” The studio never got in touch again. Lynch himself is probably the most famous surrealist director in the world. Logic is not at the forefront of a lot of his stories, endearing him to some and confusing the hell out of others. Lynch broke through with his 1977 surrealist horror film, Eraserhead, then achieved more mainstream success with The Elephant Man. However, studios quickly realized they didn’t know what to do with him after he helmed the bizarre, “Dune,” which was a failure both commercially and critically. Lynch’s most famous work is the TV show “Twin Peaks,” which became an immediate sensation upon its airing, then completely fell apart, pissing off everyone.

Writer: David Lynch

Details: 156 pages scanned (however, when transcribed to a regular document, the script comes in closer to 130 pages).

David Lynch

Okay, I swear to you. I came into this with an open mind. You guys know that I like stories which, um, make sense. So a storytelling mechanism designed to not make sense will almost always put me in a bad mood. But there are different ways to tell stories. Not everything has to have that perfect beginning, middle, and end. So you gotta be open to that, especially if you want to learn and grow as a storyteller. However, I will say this: if you’re not going to follow the traditional way of telling a story, you better be a freaking genius, and the story you’re telling better be amazing. You better wow us in ways that we’ve never been wowed. Because if there’s no direction or payoff to your script, all that’s left are the strange trappings of your mind. And we don’t want to be trapped in there with you if it’s just a bunch of bullshit.

Now to give you some background, I’m about as ignorant as they come about David Lynch. I’m aware of his career, but as for his movies, I’ve only seen Mulholland Drive and Dune. And in both cases, I was wondering what the hell was going on. I don’t think I made it through either. And that’s not through lack of trying. I was just seriously bored beyond belief and fell asleep. However, I admit I’m fascinated by Lynch for one reason: Twin Peaks. I never saw the show, but I just remember people being obsessed with it. And then, inexplicably, everyone HATED it. I don’t know what happened (or if someone can tell me), but to go from universally loved to universally hated that fast is something they write books about.

I will say this – I wish I was a surrealist writer. It seems like a hell of lot easier way to write. You never have to worry about structure or character development or any of those things that take so much time to figure out and get right. You just write whatever comes to mind “in the moment” and people either like it or they don’t. I could probably bang out six scripts a month if I followed this model. But alas, I, like everyone else, am limited by this whole “logic” issue. Sigh. Well, let’s see how much or little logic Lynch applies to this passion project of his…. Ronnie Rocket.

“Rocket” contains two parallel storylines. The first one follows two bumbling surgeons who steal a small deformed man from a hospital named Ronnie. Ronnie’s in pretty bad shape, having a hole in his face for a nose and all. So they take him to their home where they have their hospital-basement (they also live with a woman, who they appear to both be in a relationship with) and start rebuilding his face. The thing is, they’re not nearly as good at their jobs as they think they are, and end up fixing certain parts of Ronnie’s face but essentially ruining other parts.

They’re also forced to make Ronnie electrical because….well, I’m not sure why. But lots of wires are inserted into his body, and in a situation Jason Statham would be familiar with, Ronnie needs to be “plugged in” every 15 minutes or he’ll die.

Meanwhile, across the city, is this guy named “Detective.” Actually, I don’t know what his name is, but that’s what he’s called. Detective. Detective is getting frustrated because this city they’re living in appears to be getting darker and darker every day. He wants to find out what that’s all about, so he starts heading for the center of the city. Unfortunately, it’s not easy to get to the center of the city. All the trains going there close down three or four stops beforehand. So Detective must enlist the help of a punchy old man, Terry, to navigate his way to the center.

Word on the street is there’s some guy who’s responsible for all this darkness. And if they can put a stop to him, they can get this city bright and happy again. But much like Oz, he’s heavily guarded and difficult to find. He often sends out bad guys (called “Donut Men”) in trucks, who wield electricity nightsticks to beat their victims into submission. These electricity masters have so much power that by just pulling up in front of a diner, they can incite multiple seizures from the patrons, which results in many of them dying.

Back in the other part of the city, Ronnie’s stumbled into music class where, while plugged in, he begins wheezing and screaming and chirping and buzzing… but in a melodically pleasant way! Somehow his beeps and chirps mesh seamlessly with the band’s music, and the teacher asks him to join the band. Ronnie doesn’t really answer “yes” or “no,” but a vague smile indicates he’s in. Somehow, maybe, possibly, but potentially not, Detective’s quest to find the Electricity Master and take him down, and Ronnie’s own special connection to electricity (and now music) will collide and they’ll end up saving the world…or something.

What to write about a movie that doesn’t make sense… Hmmmm… Ronnie Rocket wanders off aimlessly like a dog on a walk, sniffing anything and everything that looks even remotely interesting. The funny thing is, I was so prepared for this script to make zero sense, that I was actually shocked when the screenplay started off with a goal! Detective IS after something here – the City Runner. The problem is, I was never sure why. What’s the motivation? Was it to save the city? That’s what I wrote above but that’s just me trying to give the story a point. The story itself didn’t offer one to me.

Traditionally, characters have to have motivations for doing things. And those things must be clear to the audience. That’s one of the first rules of storytelling. You can, of course, HIDE the motivation in some cases, treating it as a mystery to be revealed to the audience later, but that’s one of the riskiest things to do in screenwriting (in my opinion). If a reader doesn’t know why his main character is doing all the things he’s doing, he’s eventually going to get frustrated with him. Then again, I’m sure this is the last thing Lynch cares about. I’m betting he never sits down and says, “Hmmm, why is my character doing this?” If it pops up in his head, that’s motivation enough.

The other key screenwriting device being utilized here is the parallel storyline technique. Surprisingly, Lynch incorporates this in a fairly straightforward manner. We stay with Detective for awhile. Then we stay with Ronnie for awhile. Back to Detective. Back to Ronnie. The big key when you’re writing parallel (or multiple) storylines is to treat each storyline like its own movie. Ask yourself, “Could this storyline carry its own movie?” Because what I often see happen, and it probably happens to screenwriters unconsciously, is that they begin to think that two okay parts will add up to one great whole. Sorry, but it doesn’t work like that. My philosophy is to make the individual stories work on their own (no matter how many there are), THEN work them into the tapestry of the entire film. That way, no matter where the reader is in the story, they’re always entertained.

I wish I had more to say about Ronnie Rocket but too much of it is over my head. I suppose it’s a difference in how we like to be entertained. I like to be entertained with a well-crafted story. But plenty of people watch movies to stimulate their minds, to be challenged, to see questions posed and never answered. They don’t want the answers themselves because that means there’s nothing to discuss afterwards. What’s frustrating about this is that there is absolutely zero form to this approach. There’s no craft to it. So the line between someone who’s good at it and someone who’s terrible at it is paper thin. I mean if I’m being honest, I thought this script was a mess. Why the hell are we following Ronnie Rocket becoming a musician for 60 pages when it doesn’t seem to have anything to do with anything? And since anything is the equivalent of nothing in this screenplay, then which way is up? I’m not sure anymore. All I know is that I can’t ever read a script like Ronnie Rocket again. I might die of frustration.

[x] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: When writing multiple storylines, like in Ronnie Rocket, play a game of “top yourself.” Whatever your weakest storyline is, rewrite it until it becomes the best. And whatever the next weakest storyline is, rewrite it until IT becomes the best. Keep doing this over and over again until there isn’t a single weak storyline link in your screenplay.

Hey, who says Hollywood’s wrong by not giving a shit about writing these days? Is it REALLY that bad to go into productions with unfinished scripts? They can all point to the fact that one of the greatest movies of all time, Casablanca, went into production only half-finished! You heard that right. Casablanca didn’t have a finished script when they started filming! But here’s what’s always bothered me about this often brought up piece of cinema history. There’s a difference between “writing the script during production” and “writing an already well thought-through tightly outlined script during production.” If all your scenes are in place. If you already know how your characters are going to evolve and change. If you already know where your story is going. And in some cases, you already have the scenes thought out. That kind of “writing during production” actually still has a chance of being good. But if you’re literally making up the entire plot as you go along, that’s a different kind of “writing during production.” As much as I love Gareth Edwards as a director (the guy is going to be a freaking All-Star), you can get a sense of what REALLY going into a production without a script results in by watching his first film, “Monsters.” You’ll spot a lot of repetition, a hazy through-line, and a lack of character development, all things that need to be ironed out ahead of time. My point being, don’t think that because Hollywood lore states that Casablanca’s script was unfinished when filming began, that the underpinnings weren’t in place. It was probably mostly there. There are lots of cool other things we could discuss about Casablanca if we had more time. There were four writers revolving in and out as the script was written. A few of them had different takes on the story, making it even more miraculous that the story came together. For example, there was a lot of internal discussion over whether they should ditch the flashbacks (I personally think they could’ve). To think that they were debating the flashback device all the way back in the 1940s! That argument will never go away! Anyway, since Casablanca is well known for its dialogue, I’ll try to focus a lot of today’s tips on dialogue. But there are some other lessons we can learn here as well. Let’s take a look.

1) Combine scenes whenever possible – This is an old tip, but a good tip. Our protagonist, Rick, digs some money out of his safe for Emil, his casino runner, WHILE discussing with Casablanca’s head policeman, Renault, his planned arrest of Victor Laszlo. An amateur writer would’ve addressed each of these situations separately, taking up valuable screenwriting real estate. Pro writers combine scenes so the story moves along faster!

2) Use a clever exchange/sparring to hide backstory and/or exposition – After Head Policeman Renault tells Rick that they’re going to arrest Victor Laszlo, the writer needs to get in some backstory that Laszlo escaped from a concentration camp, as his time at the camp is an integral plot point. Now a bad writer would’ve had Rick bring this up immediately in his response, resulting in an “obvious backstory” line like, “But he escaped from a concentration camp. He’ll probably escape you.” Instead, the writer diverts attention from the line by creating a playful sparring, allowing him to hide the backstory within the exchange organically: “It’ll be interesting to see how he manages,” Rick says. “Manages what?” Renault asks. “His escape.” “Oh, but I just told you.—“ “—Stop it.” Rick replies. “He escaped from a concentration camp and the Nazis have been chasing him all over Europe.” The sparring here makes the backstory line invisible.

3) For good dialogue, make sure each character has a set of clearly defined opinions about the world/life – The more you know about your characters, the more likely they’ll deliver good lines of dialogue. Let me give you an example. Early in the script, Renault tells Rick’s head waiter, Carl, to give our villain, the Nazi Major Strasser, “a good table, one close to the ladies.” Now say the writer knows nothing about his waiter, Carl, here. Most bad writers wouldn’t. They’d say, ehh, he’s a minor character. I don’t need to know anything about him. In that case, you’re likely to get a weak generic line, something like, “You got it, boss.” But had you given some thought to Carl, you may have decided he harbors a deep resentment towards Nazis, and likes to get in subtle digs at them whenever possible. Now as you approach his response, you have a lot more to play with. It is for this reason that we get the line in the script, which is a thousand times better: “I have already given him the best, knowing he is German and would take it anyway.”

4) When placing a bunch of characters together, make sure that every single character has an angle – This is what’s so great about Casablanca. There isn’t one person in this bar who doesn’t have an angle, who isn’t looking to push their own agenda. Ugarte wants to sell those Visas. Renault wants to impress Strasser. Strasser wants to take down Laszlo. Laszlo wants to escape to America. Rick wants to avoid Ilsa. Ilsa wants to talk to Rick. And to take it one step further, make sure a lot of those angles clash. That’s where you get conflict, which is where you find drama, which is how you entertain audiences. That’s basically Casablanca in a nutshell.

5) Whatever your character’s flaw is, make sure you write a scene that shows that flaw as a choice – Here, Rick’s flaw is that he only cares about himself. He doesn’t stick his neck out for anybody. Therefore, a scene is written where he can either save Ugarte (the man who gave him the visas) or let him be arrested. Ugarte pleads for help from Rick, but Rick just stands by as he gets arrested. Through that choice, we learn his flaw.

6) Stating one’s flaw out loud is no longer in vogue – It’s one of the most famous lines in cinema: “I stick my neck out for nobody.” And yet if you used it today, it would feel way too on-the-nose. Go with an action, as explained in the previous tip, instead. Action (show, don’t tell) always has more of an impact than words.

7) Be “disagreeable” in your dialogue as much as you can – A cute and simple way to spice up dialogue is to never have characters agree with what is said. Have them add resistance or conflict or obstacles or opposing reactions. So when the German, Strasser, says to Rick, “Do you mind if I ask you a few questions? Unofficially, of course.” Rick doesn’t respond in the positive with, “Sure.” He turns it around and says, “Make it official, if you like.” If characters are just agreeing with each other all the time and having really easy conversations, there’s a 99% chance that those conversations are boring as hell.

8) Never underestimate the power of sarcasm during dialogue. It almost always makes the dialogue more fun – When Strasser asks Rick, “What is your nationality?” Rick doesn’t respond with the boring, “I’m a bar owner, in case you hadn’t noticed.” He replies. “I’m a drunkard.”

9) Add extra people to your dialogue scenes – There’s rarely a scene in Casablanca with just two people. I don’t think it’s any coincidence, then, that the movie is known for its great dialogue. Extra characters act as agitators and obstacles to dialogue, which forces characters to be more creative in the ways they talk with one another. Woody Allen, another great dialogue writer, uses this approach a lot as well.

10) Make the “other man” tough to leave, as opposed to easy – Remember that drama usually thrives on tough choices. If you make the choice for any character too easy, it’s obvious what will happen, which is boring. Make it difficult, and the audience will be hooked, as they’ll be unsure what choice the character will make. Here, the “other man” (Laszlo) is about as good a man as they come, so we really have no idea who Ilsa is going to choose, him or Rick.

11) Unless the boyfriend/husband is also the villain – There are certain situations/stories where the “other man” is also the villain. He’s beating our heroine or is the “wrong guy” for her. In those cases, it’s okay for him to be bad. But if the other man isn’t the villain in the story (here, the Nazi, Strasser, is our villain), consider making him a “good guy,” as that’ll make our heroine’s choice tougher, and therefore more dramatically compelling.

These are 11 tips from the movie “Casablanca.” To get 500 more tips from movies as varied as “Aliens,” “Pulp Fiction,” and “The Hangover,” check out my book, Scriptshadow Secrets, on Amazon!

These are 11 tips from the movie “Casablanca.” To get 500 more tips from movies as varied as “Aliens,” “Pulp Fiction,” and “The Hangover,” check out my book, Scriptshadow Secrets, on Amazon!

Can this writer pull off one of the more ambitious concepts I’ve seen all year?

Genre: Thriller

Premise: (from IMDB) If on one night every year, you could commit any crime without facing consequences, what would you do? Over the course of a single night, a family will be tested to see how far they will go to protect themselves when the vicious outside world breaks into their home.

About: Writer James DeMonaco got his career started by writing the 1996 Robin Williams vehicle, Jack, about a child who ages four times faster than other children. He went on to write The Negotiator and the remake of Assault on Precinct 13 and executive produce the TV version of “Crash.” He appears to have a good relationship with Ethan Hawke as they’ve been involved in several projects together (Assault, Little New York, and now The Purge). DeMonaco made his directing debut with Little New York, and appears to be going a lot darker with his sophomore effort. The Purge stars Ethan Hawke and comes out later this summer.

Writer: James DeMonaco

Details: 94 pages (July 6, 2011 draft)

I was very confused while reading this. The story was compelling, packed with conflict, explored its characters, moved along quickly, all things you’d expect to see from a professional screenwriter, yet it instituted the “WALL OF TEXT” method of writing, with endless paragraphs dominating every page. Okay, maybe not “endless.” They were 4-6 lines long. But if you pack enough 4-6 line paragraphs together, the task of reading becomes unbearable. It takes twice as long as it should to get through every page. So I was wondering why someone who so clearly understood drama and how to craft a story was making such a basic mistake.

Ohhhhhh, I said when I did research on the writer – he was directing the script too. Now it made sense. The director wanted to be as specific as possible so he could remind himself what he was trying to do when filming began. Well, don’t let that fool the rest of you spec writers. If you’re not directing your own material, you want to keep it lean – way leaner than this.

Now heading into The Purge, I was dying to figure out one thing – how the hell they were going to pull off this premise. One of the things you’re taught when you first start writing is the idea of “suspension of disbelief.” You have to create a scenario that an audience will buy into, that they’ll “suspend their disbelief” for. If you make it too hard for people to believe in your story, nothing else matters. They check out before the story’s even begun.

And this idea had “disbelief” written all over it. Under what circumstances would a country willingly allow its people to rape, maim, torture and kill for 12 hours a year? Well, the script answers that question in a semi-satisfactory way in that it introduces a world pretty foreign to our own. We’ve gone through TWO more world wars (not just one), which has left the U.S. government money-strapped. They agree to be bought out by one of the largest corporations in the world, who then go to work on solving the biggest problem on the planet – crime.

They realize that we, as humans, commit crime, in part, due to our biological needs. We are a savage species, and therefore need that outlet. That’s how the company, Arcon, comes up with the idea to “purge” this need once a year, for 12 hours. It’s a bit of a stretch but DeMonaco is a good writer. His attention to detail and the extensive backstory behind the corporation and how it operates makes the situation fairly believable.

The story centers around James Sandin’s upper class family. James lives in a perfect suburban community with his wife, Mary, his 16 year old rebellious daughter, Zoe, and his bizarre 12 year old son, Charlie. James sells upscale home security systems, almost specifically for that one night a year of The Purge. His security system basically turns a house into a fortress, and it isn’t just others’ homes he does this for. He’s fortified his own house with the Purge Stopper as well.

And you know what? That fortress works. What James has to worry about, however, are the members of his OWN family. As The Purge begins, James quickly finds out that Zoe’s boyfriend, Henry, is hiding inside the house so he can kill him, his logic being that James is preventing Henry and Zoe from being together.

Then his semi-retarded son, Charlie, notices a bruised and bloodied man running from, what he assumes to be, hunters, and actually OPENS THE DOOR for him. So now we have crazy Henry the boyfriend inside AND this mysterious bloodied stranger. As James tries to get a handle on the situation, Henry tries to kill him. James survives, but this allows the stranger to disappear into the house.

Soon after, a band of 20-somethings dressed in some really spooky outfits surround the Sandin house and begin demanding the release of the victim (our mysterious stranger). If James doesn’t return him alive, they will infiltrate the house and kill everyone in it. This task is made harder when Charlie rebels against his father and helps the stranger hide. And then when a third faction of people move in to also have their way with the Sandins, we get a front row seat to just how crazy The Purge can get.

Okay, first thing’s first. When you have a really big concept, it’s my belief that your first scene must represent that concept! You have to show off why the concept is so awesome and therefore why we should keep reading. This is a movie about people being able to commit crimes unimpeded. So this movie should’ve started with someone performing some horrifying crime on the streets, doing something unimaginable to someone, and a police officer standing nearby just watching, not doing anything. Show off your darn premise in that opening scene!

On to the actual story. The Purge was pretty good. But here’s my issue with it. When you’re doing something dark, you gotta go dark. If you go that “safe dark,” it always feels a little cheap. What I mean is, James kills someone in the early part of the story, as he’s participating in the Purge. But it turns out the guy WANTS to be killed because he has cancer and wants the life insurance to go to his family. He’s willingly offered himself to be killed. I think it would’ve been more interesting if our main character took full advantage of this day and committed some horrifying crime himself. Now I know how difficult that would be. It makes our hero “unlikable,” but you have to figure out a way around that. This is such a nasty premise. If you’re tip-toeing around it, you’re not getting the most out of it.

But the reason it still works is because DeMonaco knows how to keep the story moving (despite the wall of text). He does a great job building the suspense. We know the Purge is coming and we know it’s going to be crazy. So that first act zips along. Then when the Purge arrives and we find out Zoe’s boyfriend is in the house to kill James, things pretty much motor along from there. There is literally never a dull moment. Something is ALWAYS happening. And that’s not easy to do when you contain your story to a single location the whole movie.

To be honest, where The Purge starts to stumble is that TOO MUCH starts to happen. I mean we end up having four different factions looking to Purge at one point, and instead of achieving the desired chaos the script is going for, it just begins to feel sloppy. I’m not saying it’s bad. I just noticed my attention starting to wander. And the third act is where the reader’s attention should be its most focused, not its least.

I also had a huge problem with Charlie, the 12 year old son. I love when writers add depth to their characters, give them quirks and characteristics that make them stand out, that make them unique. But if those characteristics are never explained, the character ends up feeling false, like they were added to check some screenwriting book boxes, not because they were required for the story. Charlie “layers” here. He wears like 4 or 5 shirts and underwear at a time. A big deal is made out of this early on, so you’re expecting to get an explanation at some point. But it never comes. I also didn’t understand why he was so adamant about letting this criminal into the house, then hiding him, even though he understood that doing so meant his entire family would be slaughtered. It’s not like we experience some early scene where we see how important life is to Charlie. We instead get him putting on 20 t-shirts…????? This character just needed some damn explanation. You can’t create a weird character for the sake of creating a weird character.

But in the end, this “Hunger Games” meets “Funny Games” concoction has just enough to keep us entertained. I just wish the story was a little cleaner in the final act.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: This is a GREAT reminder that a cheap-to-shoot high concept idea will always be the most likely spec to sell. This idea is huge, yet its contained to one house. Someone was guaranteed to buy and make this, even if the writer wasn’t the director.

note: Scroll down for the weekend’s Amateur Offerings post!

Hey everyone. Carson here. Today we have a very familiar guest poster, professional screenwriter John Jarrell. You may remember John from his Hollywood Horror Stories post a few months back. John wanted to write another article for the site, but this time focus a little less on horror and a little more on hope. Hence, today, John will be discussing that moment every writer dreams of – his first screenplay sale. As you may remember from his last post, John runs an awesome screenwriting class here in LA, one of the few held by actual working screenwriters. This man not only tells how you how to write what Hollywood’s looking for, but explains how to navigate the elusive trenches that only those with experience in the industry know how to navigate. If you feel like your writing has stagnated, if you don’t know where to go next, or if you just want some really awesome instruction, check out John’s site to learn more about him, then sign up for his Tweak Class. You won’t regret it!

Trust me — nothing will ever quite match the crack-high of earning your first real money from screenwriting.

Experienced this yet? You and your bros crash some screening, party, mixer. People (even women!) ask what you do. You admit that you’re a (cough) screenwriter.

Great, they say, wow. Anything I’d be familiar with?

Not yet, you explain, you’re unproduced and haven’t sold anything… but Lionsgate is really, REALLY excited about a project of yours, and it could be any day now…

And that’s pretty much where the pussy hunt ends.

Because other than credits and/or money, there’s no standard by which civilians and Industry insiders can possibly differentiate between those working hard to become legit screenwriters and the army of ass-clowns out there just playing at it.

So… what’s an aspiring screenwriter to do? How can we rid ourselves of this dreaded Wannabe Syndrome, shake the metaphorical monkeys clawing at our backs? Parents, classmates, landlords, loan collectors, the faux-hipster who spotted you Twenty at The Farmacy, and, most importantly, our own stratospheric expectations?

The answer’s pretty straightforward.

Get paid for your screenwriting.

Bury a fifty-foot putt. Knock the guy through the ropes. Or as DMX so succinctly puts it, “Break ’em off somethin'”.

Because rightly or wrongly, the business of screenwriting ultimately comes down to convincing a complete stranger to give you real money for something you typed into Final Draft.

Actually, this is great news – that part about strangers paying money for scripts. Because they’re still doing it, making the blank page the great equalizer for us all, every screenwriter’s secret weapon.

Yeah, sure, no shit, John. Love the concept. But where the hell does one even START in this godforsaken town? By what means do you actually propose to get this done?

Bottom line? By any and all means necessary. Hard work. Blind luck. Freak breaks. Perfect timing. Brute Force.

At least that’s what worked for me.

*********

Before you can get paid, however, you need an agent or manager. Getting my first agent is one of those bizarre, by-the-seat-of-your-pants Hollywood stories.

Summer 1990, my actor buddy Mike was cast in perhaps the most nonsensical martial arts movie of all-time — Iron Heart starring Britton Lee. Britton was actually Korean, not Chinese, and shouldn’t be confused with Bruce Lee, Bruce Le, Bruce Li, Dragon Lee, Bruce Dragon Li, or any other Enter The Dragon copycats of that era.

Shooting was in Oregon, and late one night Mike went to a wedding party at the Portland Marriot. The bash got crazy loud, completely out of hand. Two women from an adjoining suite came over to complain, but rather than turn the racket down, the Groom convinced them to stay and party instead.

The blonde one was hot, and my bro took a liquored shine to her. Mike’s a pretty handsome guy (he became a Network soap star years later) and so he followed Young MC’s advice to the Pepsi Generation to just “bust a move”. (Under 30? Google it.)

Small talk kicked up. “Where are you from?”, “What do you do?”, etc.

So she tells Mike she’s a literary agent in Los Angeles.

And Mike, bless his heart, blurts out — “Wow. I know about the best script!”

Cue needle scratching LP surface. This chick’s looking at him like, I’m on vacation, in Portland Fuckin’ Oregon, and I’m still getting scripts thrown at me!”

But he kept her talking (like I said, Mike’s pretty hot himself) and put it out there that I’d gone to NYU and long story short, she told him this —

“If you’re serious, leave a copy at the front desk and I’ll have somebody in L.A. look at it. I fly out at 6 a.m. tomorrow.”

Want to know if your best buddy is the real deal? Here’s the gold standard.

Mike hauled ass back to his hotel, got the only copy of the script within 3000 miles, penned a quick note with my contact info, then drove all the way back to the Marriot again, at 3 a.m., and left my script for her.

Raises the bar pretty damned high, doesn’t it? Saying nothing of the fact he could’ve gotten laid if he hadn’t decided to hook me up instead.

Next morning, Mike hipped me to what happened, and I was like, great man, thanks, really appreciate it… and promptly forgot all about it. I’d already had my ass kicked so many times over that script I’d given up all hope. Shitty coverage, angry agency rejection letters, demoralizing notes from two junior, junior, baby execs, all that. A man can only eat so much shit in one sitting.

But one week later I found a message on my Panasonic answering machine.

“Hi, I’m Susanne Walker, from the New Talent Agency in Los Angeles. I’d like you to call me back. I read your script and I think it could be very, very big.”

Completely blissed out and brimming with newfound hope, I drove down to L.A. in my ’66 Bug, $200 to my name, ready to take my rightful place astride the Industry’s brightest and best paid.

Susanne got me meetings everywhere. Mace Neufeld, Scott Rudin, Paramount, Warners – all the Town’s heavy hitters. This was Ground Zero of the ’90’s Big Spec Era. It was ridiculous then, like a cartoon when compared to today’s Business. Writers were selling dirty cocktail napkins sketched with story ideas for a million cash. As the trades boldly confirmed each morning, with a decent script, anything and everything was possible.

There was only one little glitch.

Bad timing.

My script was essentially Taxi Driver meets Romeo And Juliet. Two tough Irish kids, living in the burned-out bowels of Jersey City get in trouble with black gangsters and the Mob, gunplay and tragedy quickly to ensue. People loved the gritty action and characters, and it was the type of genre film Studios were still interested in making back then.

But then State of Grace opened, just as I was taking all these meetings, I’m talking same exact week. Even though it boasted Sean Penn and Gary Oldman, it completely cratered at the box office, sinking its home studio, Orion.

Everybody agreed, our stories were COMPLETELY different. But they did share the same world, and quite literally overnight, all my hard work turned toxic, Fukushima’d by State of Grace’s blast radius.

One veteran producer put it perfectly — “It’s a shame one big, dumb movie out there is going to kill your sale.”

And that’s exactly what happened.

My new agent had nothing for me after that. One unknown with one good unsold spec wasn’t any more likely to get an open writing assignment back then than they are today. All she could suggest was to write another spec — the last thing on Earth any aspiring screenwriter wants to hear.

I got pissed. Mega-testosterone, 24 year-old white-boy pissed. I cursed the Film Gods for crushing my quick sale and the lifetime of Hollywood leisure to follow. Bitterly, I resolved to knuckle down and write that second goddamn script, vowing it would be so good that some stranger would be forced to give me money for it — they simply wouldn’t be able to help themselves.

Mike moved down to L.A., and together we took shelter in an old beach studio. Venice in ’91 was a dicey shithole, not the Pinkberry/ iPad skinny jeans love-fest you know now. Borrowing a PC, desk and chair from our dope-harvesting landlord, I barricaded myself inside our place and went on a screenwriting killing spree.

Grinding day and night, punching out page after page, wearing nothing but a bottomless bowl of Cheerios on my lap, I summoned the gripping tale of a Brooklyn attorney who witnesses a murder committed by a Mafia client he himself got off in court. When the attorney threatens to testify, the Mob comes after him and his family, gunplay and tragedy quickly to ensue.

Twenty-four days later, I chicken-pecked “The End”. I entrusted my magnum opus to Mike, holding his Backstage hostage until he read it. He finished, grinned and said — “If someone doesn’t buy this, I don’t know what to say.”

Flushed with pride and riding the final, indignant fumes of my prior rejection, I pointed The Bug down to my agent’s place. I remember bulldozing into her office like I was storming the Bastille.

“Here it is, my new spec, exactly what you asked for,” I stammered, thrusting it towards her like a broadsword. “I believe this is The Big One.”

“Okay, swell, thanks for driving in,” she said, ward nurse handling potential mental patient. “I’ll call you the second I’ve read it.”

Standing next to her desk was a stack of client scripts maybe twenty, twenty-five specs tall; a Xeroxed, three-bradded Leaning Tower of Pisa. In harrowing slow-motion, she took my newborn masterpiece and discarded it atop of the pile. Number Twenty-Six.

Something about it just broke me.

In that dark instant I got my first, unfiltered snapshot of how infinitesimal my odds really were — and it ruined me. Like they say, when you’re walking a tightrope, never, ever look down…

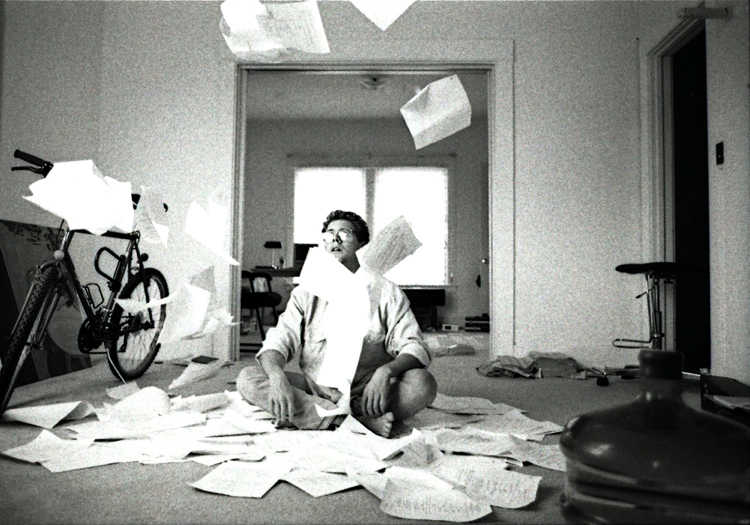

Returning to Venice, expecting the very worst, I marched into my half of the hovel and hand-shred all my notes; stepsheet, page revisions, all of it. Then I staggered, crushed, to the Boardwalk, bought a pair of 22 oz. Sapporo’s, found an empty bench and got ridiculously, pathetically, shithoused blind drunk.

Like a little baby, I cried out there, a six-foot, 190 lb. pity party. I bawled my fuckin’ eyes out among the hacky-sackers and forlorn homeless, casting my broken dreams atop the invisible, flaming bonfire of their own.

So this was the real Hollywood, I thought. The one every B-movie, t.v. show, and Danielle Steele beach-book warns you about. A financial and emotional Vietnam from which cherry young recruits like myself never returned.

Fuck me. How in the hell could I have thought selling a script would be that easy?

*********

Alas, Dear Reader, I’d overreacted. Turns out, I had not been irrevocably voted off Screenwriter Island.

Susanne called three weeks later. The ol’ good news/bad news.

Good News — She liked my script and thought it could sell. You heard me — sell. For money. Awesome, right?

Bad News — She felt it needed an entirely new Third Act. She wanted to throw out everything I had and rethink the whole thirty pages from square one.

Sooner or later every screenwriter’s life reaches a crossroads where the whole of their career — the full possibility of what they may or may not become — comes to rest in their own fragile hands. In that brief instant, there’s nobody and nothing to rely on save your own gut instincts – not unlike the process when any of us face the empty page. All the solemn risks and rewards rest squarely on your slumped shoulders alone.

My own crossroads came very quickly. On this very call, in fact.

Susanne insisted on a new Third Act before she’d go out with it. Not only didn’t I want to do extra work, I honestly wasn’t sure it was the right call creatively. I was exhausted, beaten down, my self-doubt was flaring up, and the Imposter Syndrome had me by the throat. The concept of more time in isolation, the unique self-loathing only a screenwriter knows, was simply too much to bear.

So, brain racing, I decided to sack up and posit this —

Why not cherry-pick one of the many esteemed producers we’d met when I first hit town, slip the draft to them and get their opinion?

It seemed the perfect solution. We could get an objective, world-class opinion without exposing the script and burning it around town. Further, the producer’s take would be our tie breaker. If he/she agreed with Susanne, then I’d get to work on the third act straight away, without another whimper. Conversely, if the producer agreed with me that it was ship-shape and good to go, we’d fire things up and paper the town with it.

Susanne liked the idea. Now all that remained was to choose the producer.

We picked Larry Turman, the wise man who produced The Graduate. Larry was a real straight-shooter with a ridiculous wealth of experience.

Susanne messengered my script (remember those days?) over to Larry’s office on the Warner Hollywood lot, and a few weeks later his assistant called saying Larry wanted me to drop by and talk about what I’d written.

Enduring the endless crawl up Fairfax that day was awful. That Third Street intersection has always been a clusterfuck, long before The Grove arrived. Legions of ornery blue-hairs shot-gunning in and out of the prehistoric Vons parking destroyed traffic with a sadistic regularity.

Running way late, tragedy struck. I stepped down on the clutch and SNAP! the clutch cable broke. I actually heard it shatter, like a little bone, and the pedal sank straight to the floor, useless as a severed limb.

No clutch, no drive car. Simple as that. If your clutch goes AWOL, it’s game over. You pull over, Siri Triple A and wait.

But I still had one blue-collar trick up my sleeve. True fact — you can drive an old VW without a clutch. Here’s how. Turn the engine off, cram the gearshift into first, then restart it. Your Bug will lurch and whiplash terribly, then start grinding forward. If you match the RPM’s just right, you shift back into second, too — top speed, 20 mph.

So that’s what I did, said “fuck it” and snailed onward, my Bug’s antiquity a sudden asset in my favor.

This went down at Third and Fairfax, Clusterfuck Central. Hazards on, I politely edged to the shoulder, but that did nothing to halt the on-coming bloodbath. Apoplectic motorists began HONKING AND CUSSING ME OUT as they passed. Every single motorist had their horn pinned down and/or were commanding me to forcibly insert my Bug into my own colon. Zero mercy. Welcome to L.A.

This road-rape only encouraged me. Smiling my best “fuck you, too”, I continued surfing the glacial grind towards Warner Hollywood.

I was shown into Larry’s office a humiliating forty minutes late. Here I was, this Dickensian scrub, some hat-in-hand wannabe, accidently insulting the only ray of hope I had in Hollywood.

Besides being mortified, I also looked like shit now. Oil-smudged hands, pit stains pock-marking my only clean shirt, hair matted flat to my humid skull.

“Larry, I’m really, REALLY sorry. My sincerest apologies.”

I’d blown it, and I totally accepted that. No doubt, it was a colossal bed-shitting, one I’d have to live with forever. But Larry was legitimately one of the nicest guys I’d met since crossing over the River Styx — hell, he’d actually taken time to read my script as a courtesy! — so I felt it important he know my fuck up was not intentional.

“Believe it or not, I drive an old Bug, ’66 actually, and the clutch broke. Those last two miles I had to baby her in, at, like, ten miles per hour.”

Larry peered back. What sense he might make of these ramblings, I had no clue.

“Well, your car may not be working too well, but I know something else that is.”

“Huh? What’s that?”

“Your brain,” Larry said. “You’ve written a really good script here…and I want to buy it.”

I am Jack’s completely blown mind.

“You’re fuckin’ with me, right?”

“Not at all, John. We’ve partnered with a venture capitalist, and I want to acquire your project with some of the development money we have.”

By naïve force of will, what Orson Welles once called, “The Confidence of Ignorance”, trusting my gut and a shit-ton of hard work, I’d fought my way onto the big board. I was now a paid writer.

*********

Money changed hands, and that changed my life, forever.

I was working a $125-per P.A. gig at Magic Mountain when I got The Call. Over the payphone, Susanne confirmed the deal had closed. Tomorrow, I’d have a check for $25K in my pocket, with the promise of THREE-HUNDRED THOUSAND MORE once we set it up.

Believe me, it felt EPIC. Something I pray every last one of you tastes someday. Think Tiger Woods, ’97 Masters, triumphant fist uppercutting Augusta sky, Barkley suplexing Shaq flat on his back, Hagler/Hearns with Marvelous alone still standing.

Oh, and by the way, Susanne was right — it did need a whole new third act. Five of them, in fact. And I started working up the first Day One/Page One with Larry.

Looking back, who knows? Maybe Susanne’s approach would’ve been best. Maybe if I had rewritten the Third Act in-house, we’d have sold it for even more money; started a bidding war, landed a massive, splashy spec sale putting me squarely on top.

But for me in ’91, there was no tomorrow. It was land this script, now, or beg my folks for airfare and crawl back to N.Y.C. busted apart. Many times, I’ve reflected about how not getting it done would’ve affected me, as both a writer and a man. Thank Baby Jesus, I never did find out.

Of course, here’s the punch line, the part I had no idea about —

This was just the first, brutal step of my climb up Screenwriter Mountain. Game One of a seven game series that would eat up a full decade, with a thousand times the agony of this little walk in the park.

Eventually, though, I’d pay off my student loans with a single check. Realize the Great American Dream and buy my parents a house, then grab a vintage Marshall and Gibson SG I’d always masturbated myself to. But meeting after meeting, script after script, I kept driving my trusty ’66 Bug as a reminder to keep my head on straight, come what may.

If you take nothing else away from my mangled musings, let it be this —

Screenwriters are special. Americans in general are taught never, ever to say that; never to imply any relative value between ourselves and our neighbors. But the fact remains — we writers have undertaken special challenges, endured special risks, absorbed a special amount of punishment and persevered with a special amount of grit, determination and (hopefully) integrity along the way. Screenwriters make a spectacular effort to scale our mountain of dreams while the majority of others huddle in the warmth and easy shelter of the base camps and ski lodges below.

So yeah, by any and all means necessary. Work hard. Trust your instincts. Fight like hell to spin every setback, every strand of Hollywood bullshit into gold.

And on that glorious day when you finally see an open kill shot, take it, my friend. Bury it right between the eyes.

Carson back again. I don’t know about you. But this sure makes me want to go write. Once again, John’s classes start THIS MAY in Los Angeles. So get over to his site now and SIGN UP! He only has a limited number of slots open!