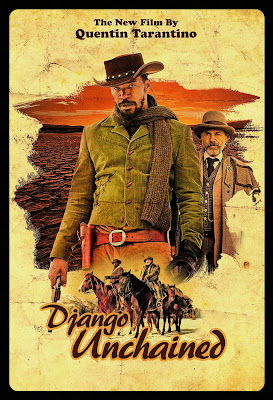

Genre: Tarantino

Premise: (from IMDB) With the help of his mentor, a slave-turned-bounty hunter sets out to rescue his wife from a brutal Mississippi plantation owner.

About: This is the next Quentin Tarantino film, coming out Dec. 25. Django Unchained stars Jaime Foxx as Django, Christoph Waltz as Dr. Schultz, Leonardo DiCaprio as Calvin Candie, and Samuel Jackson in the fearsome role of Candie’s 2nd hand man, Stephen. QT has wanted to do something with slavery for awhile, but not some big dramatic “issues” movie. He wanted to do more of a genre film. Hence, we got Django Unchained!

Writer: Quentin Tarantino

Details: 167 pages, April 26th, 2011 draft

These days, much of the time, I read scripts with a workman-like focus. That’s not to say I don’t enjoy reading. I love breaking down screenplays. But there’s always another script to read, another friend or consult or review to get to. Which means I have to stay focused, I have to get everything done.

Rarely do I read a script where I turn off the script analysis side of my brain and just enjoy the story. It happens two or three times a year. With Django, it actually went beyond that. Halfway through the script, I was so pulled in, I canceled everything and made a night of the second half of Django. I cooked dinner. I opened a nice bottle of wine. I pushed back deep into the crevice of my couch. I ate, drank and read.

Okay okay, so I didn’t actually cook anything. It was a lean cuisine meal. And I popped open a bottle of coke, not wine. I hate wine. But the point is, Django Unchained was that rare reading experience where the rest of the world disappeared and I just found myself transported into another universe.

And you know what? I’m not sure why the hell this thing worked so well. It was 168 pages. There was usually more description than was needed. Many scenes went on for ten pages or longer. BUT, Tarantino found a way to make it work. What that way is, I can only guess. Maybe it’s his voice? The way he tells stories makes all these no-nos become hell-yeahs. And that’s not to say he bucks all convention. There’s plenty of traditional storytelling going on here. It’s just presented in a way we’ve never quite seen before.

Django’s a slave who’s recently been purchased by a plantation owner. Part of a bigger group, the slaves are being transported to the new owner’s farm. There are a lot of nasty motherfuckers in this screenplay, guys way worse than the brothers pulling Django along this evening, but these men are still the kind that need a good bullet in the head to remind them of just how shitty they are.

Enter an upper-class German gentleman who appears out of the woods like a ghost. Dr. King Schultz is as smart as they come and as polite as you’ll ever see, and he’d like to ask these brothers which slave here goes by the name of “Django.” Predictably irritated, the brothers tell him to take a hike or take some lead. While respectful, Dr. Schultz doesn’t like to be told what he can and cannot do. So he smokes one of the brothers, disables the other, and makes Django a free man.

You see, Dr. Schultz is a bounty hunter. He gets paid lots of dough for the carcasses of wanted men. And it appears he’s looking for Django’s former owners, three rusty no-good brothers (there are lots of siblings in Django Unchained) who’ve changed their names and are hiding out on some plantation. Dr. Schultz will pay Django a nice sum if he can identify these men so he can kill them.

Now these men also happen to be the men who raped and branded his wife, Broomhilda. So yeah, Django knows who they are all right. He’ll help the strange German. Plus, with the money he earns, he can go off and search for his wife, who’s since been sold off to another owner. Django doesn’t know who or where, but Schultz tells him he’ll help him find her.

Away the two go, infiltrating the plantation where the brothers are hiding out, and Django gets some sweet revenge on his former slavers. The two are such a great team that Schultz recommends they extend their contract and start making some real money upgrading to the big names, the kind of names that need two people to take them down. Besides, he persuades Django, if they’re going to save Broomhilda, Django has to be in tip top shape.

So the two go off, hunting wanted men, and in their downtime, Schultz teaches Django how to read and shoot. Eventually, Django becomes the most educated badass cowboy around. And it’s a sight to see. And a sight people aren’t used to seeing. When townsfolk observe an educated free black man riding into their town on a horse, they think it must be some kind of joke. And at first, Django feels like a joke. But after awhile, he starts seeing himself the way Schultz does, as a man who deserves to be respected.

Once they’re ready, the two come up with a plan to save Broomhilda. Unfortunately, Broomhilda is being held by one of the nastiest plantation owners in all the state, a detestable villanous soul named Calvin Candie, and Calvin Candie won’t just see anybody. If you want his attention, you have to pony up. Which means Schultz and Django must pretend to be looking for a fighter in one of Calvin’s favorite hobbies – Mandingo fighting. Basically, these are slaves forced to fight other slaves for white men’s entertainment.

In their scam, Schultz will play the rich interested party, and Django will play the “Mandingo expert” he’s hired in order to find the best fighter. Calvin could give two shits about the two until Scultz says the magical words, “Twelve thousand dollars.” Now Calvin’s ready to talk, and he decides to take them back to his plantation where the talking acoustics are a little nicer, the amusement park-esque estate known as “Candyland.”

While at Candyland, the two covertly scope out Broomhilda’s whereabouts, except that Calvin’s number 2 guy, groundskeeper Stephen (who’s, surprisingly enough, Calvin’s slave), suspects something is amiss with these men, and starts to do some digging. It doesn’t take him long to figure out their intentions, intentions that have nothing to do with buying a Mandingo. He lets his boss know, and for the first time since we’ve met Django and Shultz, the tables have turned. They’re not in control of the situation anymore. Once that happens, our dynamic duo is in major trouble. And it’s looking unlikely that they’ll find a way out of it.

Let me begin by saying that a big reason this script is so awesome is because of the GOALS and the STAKES. There’s always a goal pushing the story forward, which is extremely important in any screenplay but especially a 168 page screenplay. If your characters don’t have something important they’re going after, a solid GOAL, then your story’s going to wander around aimlessly until it stumbles onto a highway and gets plastered by a semi. A gas tanker semi. A gas tanker semi that explodes and starts a forest fire.

The first goal is Schultz’s goal of needing to find these brothers. Once that goal’s taken care of, the true goal that’s driving the story takes center stage – Django needs to find and save his wife. But, you’ll notice that even when we’re not focused directly on that, we have little goals we’re focusing on. It may be to kill one of the many wanted men they’re hunting. It may be to learn to read or fight or handle a gun, so that Django can be equipped for his final showdown. QT makes sure that we’re always driving towards something here, and he does it with goals. Goals that have stakes attached to them. How can the stakes be any higher than your wife’s safety and freedom?

But that’s not the only reason. Outside of Mike Judge, I don’t know any writer who can make his characters come alive on the page better than Tarantino. He just has this knack for developing unique memorable people. I can go through 5-6 scripts in a row and not read one memorable character. This script has like two dozen of them. It’s amazing. Sometimes it’s because he subverts expectations – Dr. Schultz is a German in an unfamiliar land who’s as dangerous as fuck yet always the most polite man in the room. Sometimes it’s through irony – A slave bounty hunter hunting the very white people who enslaved him. And sometimes it’s just a name – Calvin Candie. I mean how perfect a name is that? How are you going to forget that character?

I tell writers NEVER to overpopulate their screenplays with large character counts because we’ll forget half the characters and never know what’s going on. But when you can make each character this memorable? This unique? You can write however many damn characters you please.

And the dialogue here. I can’t even tell you why it’s so awesome because I don’t know. There are certain elements of dialogue you can’t teach and QT is one of the lucky bastards who possesses that unteachable quality. But I will tell you this, and it’s something I’ve become more and more aware of in subsequent Tarantino movie viewings. He depends on a particular tool to make his scenes awesome, and it’s the main reason why he can write such long scenes and get away with it.

Basically, Tarantino hints that something bad/crazy/unpredictable is going to happen at the end of the scene, and then he takes his time building up to that moment. Because we know that explosion is coming at the end, we’re willing to sit around for six, eight, ten pages until we get there. The anticipation eats at us, so we’re biting our nails, eager to see what’s going to happen. In these cases, the slowness of the scene actually works for the story because it deprives us of what we want most, that climax.

For example, there’s a scene in the second act where the young man who’s bought Broomhilda and since fallen in love with her, takes her out for a night on the town. He unfortunately walks into one of Calvin Candie’s establishments and before you know it, Candie himself has invited him over to his table to play poker with the big boys. Broomhilda knows something’s not right, but the poor soul is too flattered to listen to her. This scene goes on and on and we see that Candie is becoming more and more sinister, and we just know this isn’t going to end well. We know something terrible is going to happen. So of course, we’re on the edge of our seats dying to see in what terrible way it will end.

Tarantino also did this, most famously, in the opening “Milk Scene” of Inglorious Basterds. A German Commander shows up at a farm house looking for fugitive jews, and we just know this isn’t going to end well. That’s why the German commander can ask for something as unexciting as a glass of milk. That’s why he can talk about mundane things for minutes on end. Because we know this isn’t going to end well, yet we’re dying to see how it does end. Go through Django Unchained again and you’ll see that there are LOTS of these scenes, and one of the biggest tricks Tarantino has in his toolbox. He keeps going back to it, and it works every time.

But what I think really separates Tarantino from everyone else is that you never quite know where he’s going to go. You can predict most movies out there down to the minute. But with QT, you can’t. And it’s because he already knows where you think he’s going to go, so he purposely goes somewhere else. Take the opening scene, where we see a polite white man being kind and cordial to a slave. Not prepared for that. Or when we see that Calvin Candie takes his orders from a black man, his slave, Stephen. Or how when Broomhilda is first purchased, she’s actually purchased by a shy young white man who quickly falls in love with her and treats her kindly. I was always trying to predict where Tarantino would go next, and I was usually wrong. And even better, the choice he ended up going with always ended up in a better scene.

My complaints are minimal. There was only one area of the script that felt lazy. (spoiler) Late in the third act, Django’s life is spared because, apparently, he’ll experience a much worse death “in the mines.” This allows him to be transferred off the plantation, which of course allows him to trick his transporters and go back to save Broomhilda. Come on. No way the Candie family doesn’t torture and kill him right there. No way they let him go off to the mines. So I was disappointed by that because it felt like a cheap way to give Django his big climax. With that said, the big climax was phenomenal. Average Joe Writer would have had Django go in there Die Hard style. QT took a slower more practical approach, and created a much better finale because of it.

So you know what? I can’t believe I’m doing this since I haven’t done it in two years before a month ago, but I’m giving another GENIUS rating. This script is freaking amazing. It really is. I don’t know if the Academy knows what to do with a movie like this, but if we’re talking writing alone, this script should win the Oscar. And, heck, it should win for best film too.

What I learned: Always look for ironic moments in your screenplay. Audiences LOVE irony. Django, a slave, must play the role of a slave driver near the end of the film. He must treat other slaves like they’re dirt. He must talk to them like they’re dirt. It’s tough to watch but also fascinating, since he himself was, of course, a slave a short time ago.

Genre: Drama

Premise: When a large natural gas corporation comes into a small town to buy up its natural gas deposits, a few resistant residents make the reps pursuit a living hell.

About: This is the script that Matt Damon and longtime “The Office” co-star, John Krasinski, wrote together. This would be the first script of Damon’s since Good Will Hunting. The film has been shot and I believe is coming out later this year.

Writers: Matt Damon and John Krasinski

Details: 113 pages – undated

Ben.

And Matt.

And Matt. And Ben.

And John?

From The Office?

Wait a minute. What’s going on here? A love triangle?

Alas, it seems the most famous bromance of the last 15 years is officially kaput. Matt has moved on to someone younger and prettier. Not sure how Ben feels about this, but maybe making the dark and brooding Argo was his way of dealing with the pain.

I’ll be honest, when I heard about Promised Land, I was worried for a couple of reasons. First off, two actors writing a script? I mean, I don’t want to stereotype or anything, but what do actors know about writing? Is that any different from Aaron Sorkin saying, “I’m going to go star in my own movie?” Even if Damon had written a script before, he certainly doesn’t have the time today that he did before Good Will Hunting. And who’s to say Krasinski can write? Why do all of these actors all of a sudden think they’re Ernest Hemingway?

And then there was the whole political thing. Damon’s not shy about voicing his political views, and I’d been told this script was a political statement about something called “Fracking.” Ugh, so now I was being preached to by an actor about his political stance on something that sounded like a bad debate topic? Kill me now.

And then I read Promised Land. And I really fracking liked it.

Closing in on 40, Steve Landsman is ready to take that big leap in his career – the one that comes with the free car, the top level medical benefits, and the bank-busting salary. He’s going to be a vice-president in one of the biggest natural gas companies in the world. All he’s gotta do is close this one last town, McKinley, NY, which should be as easy as the drive down from Manhattan.

For a little background, these natural gas companies are trying to pick up the ball that the oil companies dropped. We’re so dependent on oil-rich countries, many of which drive up the prices cause they hate us so much, and yet we have our own huge energy supply right here in our own back yard – natural gas!

This gas is buried deep in deposits all over North America, and all it takes to extract it are these big wells that the natural gas companies build. Problem is, most of the land where you find these deposits is privately owned, which means you have to pay the owners lots of money to allow you to drill on their land. Which usually isn’t a problem. Throw a million bucks at Honey Boo Boo and Co. and chances are they’re going to help you build the drill themselves. Assuming they don’t eat it first.

That is until McKinley, New York. You see, Steve and his partner, 55 year old Sue Thomason, are thrown a curve ball when one of the local science teachers, a man who used to teach at M.I.T., starts educating the townspeople on the dangers of “fracking.” It turns out that the side effects include gas-tainted drinking water, to the point where you can light an icy glass of H2O on fire! Escaped gas can also end up killing farmland and animals. You can say the word “natural,” all you want. But it’s still gas.

To make things worse, an environmentalist named Dustin moves into town representing a group called “Athena.” It turns out the science teacher spiel was only the tip of the iceberg. Dustin starts giving the town a full-on crash course in the harms of fracking. All of a sudden, money doesn’t seem so important to these folks anymore.

Back at headquarters, the company starts worrying that Steve isn’t up to the task, and considers sending in a clean-up team. Knowing that would be the end of any vice-presidential standing in the company, Steve refuses the help and ensures HQ that he can get this done. However, he has a big fight ahead of him, as it seems like with every passing hour, the town is less and less interested in buying what it is Steve’s selling.

Promised Land possesses some good old-fashioned storytelling in its bones. I loved that even though this was a “small” “independent” project, it still relied on tried and true storytelling tools, particularly GSU. The goal was to make the deal with the town’s residents. The stakes were Steve’s promotion (and potentially losing his job). The urgency was the town vote coming up. It just goes to show that simple storytelling techniques can work magic when integrated naturally.

I’ve also found that these “big city know-it-alls” vs. “small town hicks” storylines usually work. The conflict is already built into the situation. It’s a very familiar conflict at that, so it doesn’t take much for an audience to get invested. And what I liked about Promised Land was that it put you inside the shoes of the “bad guy” during that situation. That’s not easy to do because it’s hard to like the bad guy. What I think made it work though is that Steve believed he was doing good. He’s making these people rich. When he realizes maybe that’s not the best thing for them in the long run, that’s when he starts questioning himself, resulting in some inner conflict he must deal with. Any time your character has to battle with something inside himself, you’ve probably got yourself an interesting character. In all the bad scripts I read, the characters are usually too simple and have nothing going on inside. Not every hero will be struggling with something inside, but if it works for your story, I’d suggest doing it.

The script also introduced new plotlines right when it needed to. One of the common problems with amateur scripts is that they run out of story somewhere in the second act. Introducing new developments is a great way to keep the second act alive. So with Promised Land, the key development was the introduction of Dustin. Now, instead of just having to worry about the people of the town, Steve had to worry about this whole other organization, making his job even more difficult. And the way Dustin weaved his way into the very fabric of the town, even going so far as to steal Steve’s girl, made him a great bad guy.

Although I’m not going to spoil it here, I also loved the twist ending, which I didn’t see coming at all. Twist endings in scripts that don’t usually have twist endings are often the best kind, because you’re so not expecting them at all. I mean we’re not talking a Sixth Sense twist level here. But it was still a nice surprise.

I don’t have many complaints about Promised Land. I thought the love story between Steve and Alice could’ve been better handled. It felt like the writers weren’t sure where to go with it. And I thought they could’ve done more with the science teacher, Yates. It’s such a great surprise when they find out he’s some legendary professor teaching high school science here for fun. But then he sort of fades into the background, allowing Dustin to take center stage. Yates never got his moment.

I admit, going into this I expected some pretentious self-important story about the dangers of fracking. Instead I got an accessible entertaining story that nailed exactly what it was trying to do.

What I learned: Remember, if you have a main character who’s tough to like, introduce an oppositional character who we hate even more. We’ll like our tough-to-like character if only to see him topple this annoying asshole. This was the role that Dustin played in the story.

Genre: Comedy/Horror

Premise: A college student home for the holidays discovers that an internet porn film turns its viewers into homicidal maniacs. As the epidemic spreads, he has to save his longtime crush while struggling to control his own urges.

About: Adam Penn worked as an editor on Nip Tuck and, more recently, American Horror Story. He is yet to claim a feature writing credit, but did write an episode of “Black Box TV.” This script landed on the 2008 Black List.

Writer: Adam Penn

Details: 111 pages – August 4. 2008

One of the things I like to do is pull old scripts out of the Hollywood’s junk bin and see if they’re still good – see if they’re worthy of getting another shot at the title. Everyone knows this town has the attention span of a squirrel. That means the occasional quality script can surface which either isn’t marketable enough or doesn’t reach enough desks at the time, and, as a result, fade into obscurity. Which is a shame. Because every once in awhile, one of those scripts is a A Desperate Hours, or a Dead of Winter. At one point even The Grey was forgotten. I mean come on Hollywood!

So when I saw this title and this premise, I thought, “You know, if done right, it’s one of those scripts that just might be wacky enough to work.” I mean sure – it’s also one of those scripts that could go off the rails faster than a train with a texting conductor. But I was feeling lucky. What about you? Do you feel lucky? Punk?

No? Okay, I wasn’t trying to put any pressure on you. Sorry. But right. “Peacoat Miller.” I’ve labeled screenplays like this, “The Crazy Screenplay.” That’s because they throw everything and the kitchen sink at you, thinking you’ll be so delighted with all the absurdity that you won’t be able to control your laughter. We’ve seen these screenplays before on Scriptshadow. Heck, we’ve even reviewed one that was literally called Kitchen Sink. And that script was pretty good. So why can’t this one be?

Penn plops us down in Rockville, Maryland circa 2008. No, this isn’t a flashback. This is when the script was written. 21 year old Peter “Peacoat” Miller wakes up one morning staring up at a decapitated cat clockwising around on the ceiling fan. On the plus side, don’t have to budget for Meow Mix anymore. On the minus side? How the hell did this happen???

He dials up his best friend, Egyptian mega-nerd Wesam Fahmy, and informs him about the murdered cat, to which Wesam doesn’t seem too concerned. But he helps Peacoat recall what he did the night before, which basically amounted to nothing except for watching a porno clip of an “average asian chick getting it from behind.”

Well, they go back to that clip and, low-and-behold, it turns out it puts you in some sort of serial killer trance that forces you to go out and kill people in really violent ways! Like by tearing their faces off! There is a LOT of face-tearing-off in “Peacoat Miller.” Which should give you an idea of what you’re in for.

But before we get to that, Peacoat heads to his shrink, the oversexed Dr. Kaiser, to try and get some insight into why he woke up with a dead cat on his fan. It was at this point that I knew the script wasn’t going to be any good. Whenever characters go places for vague reasons, it’s a guarantee that the script is going to be sloppy. He wakes up with a dead cat on his fan so he goes to a shrink he hasn’t seen in two years?? I mean there’s sorrrrttttaaaa a kind of logical connection there but it just seems like something you’d do like 3 months down the line, not now. Clearly, Penn wanted to get the loopy sex-crazed Dr. Kaiser into the story somehow, so throwing Peacoat into a session with him, even though it didn’t make any sense, was the gameplan.

It’s at Kaiser’s offices where Peacoat runs into the sarcastic and dangerous Valentine, a girl who caught him masturbating to Jet magazine when he was a kid, and who he hasn’t spoken to since. The two engage in some flirty dialogue, and she mentions some end of the year party he should come to even though he wasn’t invited.

Peacoat’s thrilled that he and Valentine are finally talking, but has to find out about the cat murder stuff before he can book her on “Say Yes To The Dress.” He discovers that the naughty video turns you into a killer, and that he’s not the only one affected. News coverage shows people everywhere are randomly murdering neighbors…and ripping their faces off!

Which means he has to figure out a way to stop all this, especially because the love of his life, Valentine, is going to be at a party FEATURING the infamous video. EGADS!

Okay so look, I understand that when you don’t like the humor in a script, there’s no hope of you liking the script. The characters can be good. The plot can be interesting. But if you aren’t laughing at a single joke, the script is done in your mind. And to put it plainly, that’s how I felt.

But the truth is, I didn’t think there was any structure/story either. It didn’t seem like anyone was in a hurry to do anything until the very very end. So we’re going through an entire second act where characters talk about being concerned. But they don’t exhibit any traits that would make you think they were concerned.

You get some leniency in this department if you’re writing a comedy, sure, but the comedy didn’t even seem like comedy to me. It just felt like a bunch of really weird crazy shit happening. Even Dr. Kaiser, who was probably the best character, elicited only smiles. I wanted him to be funny. The idea of him was funny. But he wasn’t funny for some reason.

The dialogue also annoyed me. It felt like it was trying too hard to be clever. We get lines like, “We don’t know shit. Chick could’ve seen a mouse. I’m done playing John McClane. Sam needs to get his drink on, his smoke on. Go home with somethin’ to poke on.” I did a little research and checked out when Juno came out. Sure enough, it came out in 2007, the year before this was written, and I remember for awhile there, trying to write like Diablo Cody was all the rage. Many writers did it without even liking what they were doing. They just thought that’s what everyone wanted. It feels like Penn was one of these victims. I’m not even sure he’d be convinced that this is good dialogue.

If you want to go back to my article about storytelling, Penn is telling a story here. He starts out with a mystery. Why is Peacoat killing things? The problem is, the answer to that mystery pops up immediately. When that happens, you want to follow it with a goal. We know what’s causing this – so the GOAL should be to stop it. That should be the logical driving force for the rest of the script. And it sorta is. Except that it isn’t. Peacoat and Wesam stumble around for the rest of the script not doing much of anything. In a screenplay – especially a comedy – you want there to be a sense of urgency – a sense that things need to be taken care of now. And just saying “other people are dying” isn’t enough! We have to see your characters actively going out there and doing something about it, especially in the second act, where it’s so easy for your script to get slow. Check out tomorrow’s script review to see how to properly add urgency to your hero’s pursuit.

I wish I had some nice things to say here but this felt like one of those early attempts at a screenplay. You’re trying to write what you think Hollywood wants, instead of going with your own gut and your own voice. And because it appears Penn was still learning the craft when he wrote it, the structure was weak, making for a really uneventful second act. This one definitely wasn’t for me.

What I learned; Whenever you write a party scene (or gathering, or ball, or event) make sure to give your main character a clear objective for the party in order to keep things focused. With there being so much going on at a party, it’s easy to lose your way, or drift into tangents that the audience doesn’t care about. By giving your hero an objective, you give the part a clear focus, which should keep the sequence easy to follow. So in the case of “Peacoat Miller,” the objective was Peacoat’s pursuit of Valentine.

Genre: Contained Thriller

The Last of the DEFINITES. Sounds like a good title if anyone decides to adapt Twit-Pitch into a movie.

Make no mistake about it: Twit-Pitch and I have experienced some rocky times together. It wasn’t always spelling-mistake free first pages and freshly polished gold brads. There was that time where I realized the writer hadn’t written his script before entering the contest. Oh, and then there was that other time where I realized the writer hadn’t written his script before entering the contest. But through it all, we stuck together. Maybe longer than a lot of you thought we should. There were times when Twit-Pitch was downright abusive to me. But I remember when I broke up with Looper in front of the world. You know who the first one there for me was? Twit-Pitch. That’s who. I’m kinda gettin’ all…teary-eyed just thinking about it.

As far as where today’s Twit-Pitch script brings us? Well, here’s the thing. There’ve been flashier concepts. There’s been better writing. But reading the first ten pages of “Guest,” I thought, “This could be the one that actually gets made.” The contained thriller element – a protagonist with something under the hood – the low-budget price tag? If this thing were done right, it may be the sleeper that woke this damn contest up. Let’s find out if that was the case.

Samantha Given is 56 years old. One look at her and you know whatever roads she’s taken in life, they’re not the same roads you and I drive on. These roads are the unpaved kind, the backwoods gravel-laden pieces of shit you get lost in. She wears every wrinkle of that 56 year old face. And it doesn’t take long to figure out that’s why she’s here, checking in at this hotel. She’s sick of those f*cking roads. And she’s finally doing something about it. Even if it’s just holing up for a few days.

Now this hotel isn’t Hotel Transylvania, but it’s got its fair share of spooky shit going on. There’s loud thumping noises happening every hour or so. They actually put that famous Van Gogh Scream painting on the wall (who puts that in a hotel room?). Oh, and the bellhop, the overly polite but totally sketchy Diego, likes to get a little too personal with his questioning. Since when do bellhops ask, “So what do you plan to do for the rest of the day?” Not only that, but he seems really keen on getting Sam into a “better” room.

But Sam’s fine with the room she’s in. That is until those thumping noises start again. After awhile, Sam decides to do some investigating, listening through the wall, and starts getting this idea that someone’s being held captive in the next room. Oh, this would be a good time to mention that Sam’s on anti-psychotics. So yeah, not everything’s kosher at the top of the Christmas tree. But man does she become convinced that something’s up. So even though she knows it’s going to put her on the hot seat, she calls the cops.

The police come in. There’s a big hubbub in the hallway. The guy staying in the next room is obviously pissed. And when the police check inside, they find nothing. Not a single trace. But Sam knows something’s up. Diego, the bellhop, is always acting weird. If he were in on it, they could’ve moved the girl they’ve kidnapped. Assuming there’s a girl. And assuming all of this isn’t in her head.

If this weren’t bad enough, we’re also learning more about Sam’s past and why she’s here. Her husband, Charlie, has been treating her like a pinata for the last 30 years, and this is the first time she’s had the balls to do something about it. But Charlie’s constant calls and texts asking her to come back are starting to break her down. And Sam’s daughter, completely oblivious to the abuse her mom’s been through, is getting pissed that Sam is being such a baby.

All this leads to an increasingly precarious situation. If there is someone being held captive in the other room, Sam has to find a way to save her. If there isn’t, and she’s just imagining it all, then maybe she’s as weak as her husband’s made her out to be. And maybe her best option is to go crawling back to him, apologize, and continue to live a life of abusiveness.

Something I want to bring to everyone’s attention right away is that readers LOVE reading scripts like “Guest.” Low character count. Contained location. An easy-to-understand situation. These are easy reads! Readers know they’re not going to be taking endless notes trying to keep track of who’s who and how they’re related and how those fifteen other subplots factor into everything. And that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t go to some unexpected places with your story. It doesn’t mean you shouldn’t have complicated stuff going on with your characters. Of course you want that. But the overall story situation is easy to follow and therefore very reader-friendly.

Something else that gave me confidence in “Guest” was that the adjacent room wasn’t the only mystery. The second mystery was Sam herself. Whenever you’re writing something that takes place in a contained area, you don’t have as many places to go with your story. So it’s ESSENTIAL that you make your characters themselves a story. That way, we’re not just trying to find out what’s going on in the “other room.” We’re trying to find out what’s going on inside our protagonist.

And to that end, I think Cruz did a good job. The whole “abused wife” thing can be really cliche if done badly, and I thought Cruz brought a realism to it that made me give a shit about Sam. I believed she had this past with her husband. And I liked the parallels of her being trapped in this relationship, needing to be saved, just like this girl (if there’s a girl) is trapped in the next room, needing to be saved. Watching Sam gradually gain the courage to go from victim to hero wasn’t a perfect transition, but it was convincing enough.

The problems I had with the script mainly fell on the technical front. When you’re doing a contained thriller, I’m not sure you should ever take us outside of that setting. I believe it’s important that we feel stuck here, even if we technially aren’t. When Sam went to have coffee with her daughter, that carefully constructed fabric of danger was instantly ripped apart. I wanted to stay in that hotel. Or actually I didn’t. Which is exactly why the writer should’ve kept me there.

Also, one thing I’m always on guard with with these scripts is the writer biding time. Most writers get these ideas for contained thrillers, think they’ve struck gold, but then realize they have these huge chunks of time to fill up between the main scenes. And since the sparse setting offers little in the way of choices, these writers come up with shit for the sake of coming up with shit instead of giving us scenes that actually matter, scenes that are actually entertaining. As a result, the script slows to a crawl. Overall, I thought Cruz did a good job avoiding this but there were a good 10 pages early in the second act where Sam didn’t seem to be doing much and I started to get bored. It picked up afterwards but still, you can’t have ten slow pages in a thriller. Especially one that’s only 80 pages long.

(Spoiler) My last issue is I would’ve liked to have known more about Danielle. Why was she kidnapped? The few hints that we got indicated that this wasn’t your average kidnapping. There was more of a story to this. I was waiting for that story to be revealed but it never came, and I was disappointed by that. That could’ve been a nice final twist, if Danielle’s kidnapping wasn’t exactly what we thought it was.

But all in all, this is EASILY one of the best Twit-Pitch scripts. It probably needs to come in longer than 79 pages, but the writing here is really strong. And more importantly, the STORYTELLING here is really strong. Check this one out for sure!

Script Link: Guest

What I learned: In contained low-character count screenplays, make sure your main characters are dealing with some kind of inner conflict, some kind of troubled back-story that needs to be resolved. Because your story choices are limited in contained situations, you need an additional interesting story going on within your main character to keep us entertained.

I recently caused a minor fracas by suggesting that screenwriters aren’t “writers,” per se, but rather “storytellers,” and that if you want to become a successful screenwriter, your focus should be on telling stories rather than writing. I’m afraid that some of you took me a little too literally and assumed I meant that there’s no actual “writing” involved in screenwriting.

Writing is, of course, an essential part of telling any story on the page. If I write, “Jason, bloodied and wheezing, stumbles through the airplane wreckage, blinded by the smoke,” that’s a hell of a lot more descriptive and exciting than “Jason walks through what remains of the airplane.” To that end, writing is essential. It’s our job to pull a reader into our universe, and how we weave words together to create images and moments is a large part of what makes that process successful.

However, here’s the rub. Unless you’ve created an interesting enough situation to write about in the first place, it won’t matter how well you’ve described that moment, because we’re already bored. And that’s what I mean by “storytelling.” One must create a series of compelling dramatic situations that pull a reader in for the writing itself to matter.

So to help clarify this, here is how I define writing and storytelling and how they relate to screenwriting. Because this is my own theory, I’m not saying these are universal definitions, only definitions to help explain the points I’m making in the article.

Writing – When I refer to “writing,” I mean the way in which everything in the story is described, the way in which the picture is painted. While important, you can give me the greatest description ever of a character, the greatest description ever of that character’s house, the greatest description ever of the way he goes about his nightly routine, and the greatest description ever of a car chase he gets into later…and I can still be bored out of my mind because you haven’t preceded any of these things with a story I care about.

Storytelling – “Storytelling,” on the other hand, is the inclusion of goals and mysteries that create enough conflict, drama, and suspense to pull an audience in and make them care about what they’re watching. For example, that immaculately described car chase above is boring unless, say, the character driving has 10 minutes left to get across town and save his daughter, with the cops, the mob, and the government trying to stop him.

So how does one “tell a story?” What’s the secret to storytelling? Well, I feel storytelling can be broken down into a couple of simple components. The first is G.O.C. (Goals, obstacles and conflict). In most stories, you have a character goal – a hero who’s trying to achieve something. In order to make their pursuit interesting, you must throw obstacles at them, things that get in the way of them achieving their goal. Naturally, because obstacles prevent our hero from doing what he wants, conflict emerges, and conflict is what leads to entertainment, since it’s always interesting to see how the conflict will be resolved. If a character wants something and gets it without having to work for it, there’s a good chance your story (or at least that part of your story) is boring. John McClane’s goal is to save his wife, but the terrorists in the building provide obstacles to doing so, which creates conflict.

The other major component of storytelling is mystery. If you don’t start with a character who has a goal, you should be working to create a mystery. “Lost” built an entire show around this. From the “Others” to the “Hatch” to the “numbers entry.” We kept watching that show because we wanted answers to those mysteries. Note, however, that mysteries always eventually lead to character goals, since sooner or later a character will be tasked with figuring out that mystery (their goal). “The Ring” is a good example. A mystery is created with this video tape which kills people in 7 days. Naomi Watts’ character, then, has the goal of finding out the origins of the tape, and seeing if she can stop it from killing people.

A writer’s mastery of these two components, the goal and the mystery, are often what defines him/her as a good storyteller and determines whether their screenplays will be any good.

What I often run into on the amateur level is the opposite. I read tons of scripts where writers put all their efforts into immaculately describing their worlds, their characters, their scenes, and everything involved in painting the picture for the reader, but without any conflict or drama or suspense. It’s the kind of stuff that makes you go, “This person is a great writer!!” But in the end, there’s no immediate goal, there’s no compelling mystery. So it’s just boring shit happening. Really well described boring shit happening, but boring shit happening nonetheless. I know a lot of writers send their scripts out and get this recurring note back: “We loved the writing but the script wasn’t for us.” It confuses the hell out of the writer. “If the writing is great,” they ask, “Why the hell wouldn’t the script be for them??” It’s because your story is boring as hell! There’s not enough storytelling!

What you must do to prevent this is make sure you’re storytelling on three different levels: on the concept level, the sequence level, and the scene level. What I mean by this is that your overall concept must have a story built into it, each sequence in your script must have a story built into it, and your scenes themselves must have stories built into them. The second you’re not telling a story on one of these three levels, you’re just writing. You’re describing shit or recounting shit or laying out shit. You’re not storytelling. Let’s take a closer look at these three levels using the film, “Aliens,” as an example.

CONCEPT LEVEL – The concept of Aliens has a great story behind it. There’s a mystery: A remote base on a faraway planet has gone silent and they suspect that there may be aliens involved. This mystery leads to a goal. Ripley and a team of Marines must go in and figure out what’s happened, possibly having to wipe out the aliens. An intriguing setup for a story.

SEQUENCE LEVEL – Having a strong overall story concept is great, but you need to find a way to keep that concept interesting for 120 pages. If the characters in Aliens just go in and kill the aliens, your story is over within 30 pages. This is where sequences come in – 10-20 page chunks that have their own little stories going on. These sequences are going to have their own goals and their own mysteries. In other words, you must be telling stories within these 15 page segments. For example, the first goal is to get into the base and find out what happened. They get in there, find out everyone’s gone, and discover some traces of a battle. In the next sequence, the aliens attack, and the goal is for Ripley to get to the soldiers and save them. The next sequence introduces a new goal – figure out what to do about this. They decide to go back up to the ship and nuke the place. Except when the ship comes down to get them, it’s sabotaged by the aliens, leaving them there. — The point to remember is: with each sequence, introduce new goals and new mysteries to keep the story entertaining. If you’re not doing that, you’re just writing.

SCENE LEVEL – Storytelling at the scene level is where I can tell whether I’m dealing with a pro or an amateur. Good writers work to make every scene have some sort of mystery or goal driving it. There’s a situation that needs to be resolved by the end of the scene, and the scene isn’t over until that happens. Again, we’re talking about the same tools here. Goals and mysteries. The goal could be as simple as “making sure the area is secure,” which is what the Marines’ initial job is when they go into the base. Or the mystery can be as simple as “what happened here?” which is what drives the following scene – the characters trying to put the pieces of what happened together through the clues they find.

Each of these levels of your screenplay should be telling compelling stories or we’re going to get bored. I run into really interesting story concepts all the time that turn into boring screenplays because the writer doesn’t know how to tell stories on the sequence or scene level. It’s like they figure, “I came up with a cool idea for the movie. I’m finished.” NO! You have to come up with a cool idea for every sequence! Every scene! Think of each of those as MINI-MOVIES, all of which have to be just as compelling as the overall idea. Because I’ll tell you this: if you write three boring scenes in a row in a screenplay, you’re done! The reader’s officially given up on you. Try to tell a story every time you walk into a scene.

There are obviously smaller tools you can use to enhance your storytelling as well. You can throw unexpected twists in there, suspense, dramatic irony, a character’s inner journey. But if you’re a beginner/intermediate, focus on the basics first. Goals and mysteries. Goals and mysteries. Always remember: No matter how good of a writer you are, how strong your prose is or how well you can describe a scene, unless you’ve set up a story where we give a shit about the characters in that place, it won’t matter. Screenwriting is not a writing contest. It’s a storytelling contest. The sooner you realize that, the faster you’ll succeed in this business. I PROMISE YOU THAT.

.jpg)