Genre: Sci-fi

Premise: In a future where the world’s been frozen over, a young man on a train that never stops leads a revolution to topple the train’s tyrannical leader.

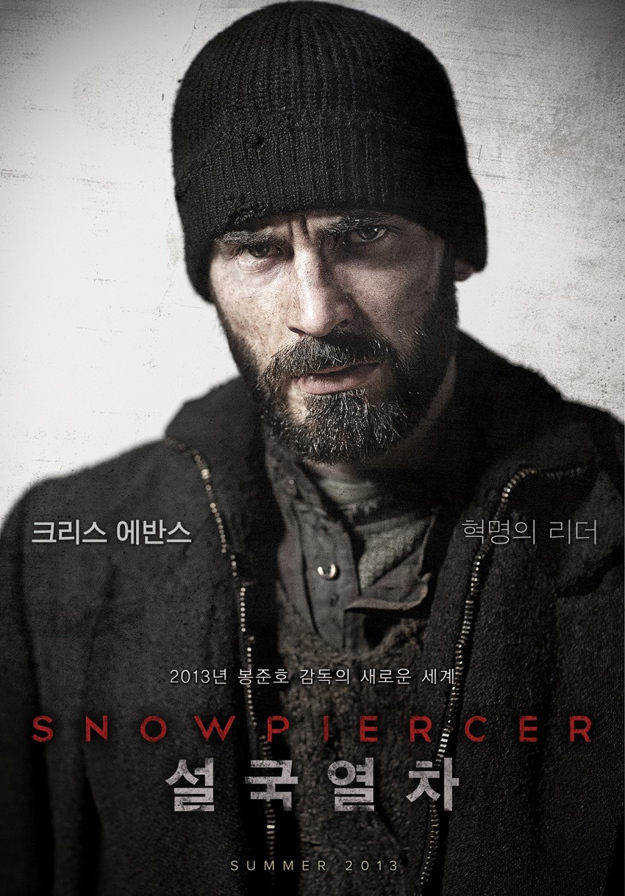

About: Snowpiercer was co-written by Korean director Joon-ho Bong, who’s making his first American film. He’s best known for his films The Host and Mother. Kelly Masterson, who made revisions to the script, wrote the excellent “Before The Devil Knows You’re Dead,” yet strangely hasn’t written anything since (that was an excellent screenplay – so I’m kinda shocked he didn’t blow up after it). Snowpiercer stars Captain America himself, Chris Evans. It’s already been shot and will be released later this year, although curiously, no release date has been set.

Writers: Joon-ho Bong and Kelly Masterson, based on the French comic book series created by Jacques Lob, Benjamin Legrand, and Jean-Marc Rochette

Details: 110 pages (final draft – 11/11/11).

Along with its cool title, hip director and shiny lead actor, Snowpiercer has itself some pretty slick visuals if you’re to go by its trailer. Ever since I saw The Host way back when, I’ve been intrigued by Bong as a director. The guy was one of the first to prove that big effects didn’t have to come from a Hollywood budget. I guess it was only natural, then, that he’d work his way over to the states.

However, the U.S. is a little different, and something I’ve noticed over time is that the Asian point of view doesn’t always translate well in the U.S. And it probably shouldn’t. Cultures are different. They like a lot of different things. I saw that earlier this year with the Chan-wook Park film, Stoker. And I saw it with The Host, too.

I bring this up because my opinion on Snowpiercer is not a good one. And I don’t know how much of that is because of bad storytelling or because of a cultural divide. But this script did not work for me. I guess because I wanted it to succeed so bad, I’m looking for excuses why it didn’t.

It’s 2031, 17 years after the world’s nations sent a chemical called “CW-7” into the air to stop global warming. Looks like their chemical worked a little too well. It’s now freezing out. Worse than a morning-Chicago-commute-in-February freezing. Almost everyone died in this global freeze-a-thon. Except for a few lucky ones, like Wilfred. Wilfred was one of the few who foresaw the chemical agent apocalypse, and so he built a train.

A train, you say? But how is a train the best option for taking on global freezing? That’s one of the many baffling questions Snowpiercer will pose. But yeah, so this eccentric billionaire built a train that travels around the world and never stops. It’s powered by a super-engine that never dies. How? Oh, you wouldn’t believe me if I told you. It’s one of the big reveals of Snowpiercer and it’s so ludicrous, I can’t repeat it. But, moving on…

So this guy, Curtis, is one of the poor souls at the back of the train. These are the nobodies, the slop, the trash. They live in deplorable conditions while the rich eat their caviar and drink their champagne in the front cars. Too bad for them, Curtis is tired of being left out. So he puts together an army to march through all the cars and to kill Wilfred.

But first he’s going to need the gate opener, Namgoong. Namgoong designed the gates between each car before becoming a Chronole addict. He’s since been sent to prison with his 17 year old daughter, who’s ALSO a Chronole addict. Curtis makes a deal with the both of them. For every gate they open, he’ll give them a bag of Chronole. They’re in.

There are others who join the charge as well. They’re Tanya, whose child was stolen by the rich. She wants him back. There’s Curtis’s best friend and second-in-command, Edgar. There’s the old man of the club, 70 year-old Gilliam. Each wants to get to the front of the train for their own reasons. Not all will make it. And the ones who do (spoiler) will be shocked to find out their revolt may not have been their decision in the first place.

Oh boy.

I mean. Okay. Wow. Snowpiercer is one of the more bizarre pieces of material I’ve read all year.

One of the first things you want to make sure of when you write a script is that your concept passes the logic test. It needs to make sense and be understandable. Because if your concept’s weak, anything you place on top of it is going to make it weaker. Things are going to start creaking. They will start buckling. And pretty soon they will all fall down.

The concept in Snowpiercer? It’s the future. We’re in a self-imposed ice age. So in order to battle this a man builds… a train?? I’m sorry but how does this make sense? There is no connective logic there whatsoever. How does a train stave off cold? Wouldn’t it be a billion times easier to build a bunker? I mean then you wouldn’t have to worry about maintaining 30,000 miles of track over the course of 20 years, right?

To me, this was the script-killer of all script-killers. The mythology here was just too poorly thought-through. Nobody sat down and thought past the cool-factor of each idea. I mean, when you watched The Matrix, you got the sense that the Wachowskis knew their world inside-out. Even if you thought some of it was weird, you knew they knew it. That isn’t the case here. Most of the stuff feels like a sixth-grader thought it up and everyone just went with it without a second thought.

There were also some really goofy choices here. For example, one of the train cars they have to go through is a club. Like, “boom boom boom” – a dance club. In a world where these are the last remaining humans and every square inch of living space is vital, why are they wasting an entire train car on a club???

We also get weird lines of dialogue, like when one of the rebels throws a shoe at a guard, the resulting tantrum results in this line: “This is disorder. This is size ten chaos.” Or when it’s revealed that Curtis had to resort to cannibalism before he was on the train, he offers this line, “Do you know what I hate the most about myself? I fucking hate that I know what part of a human tastes good. I know that young babies taste the best.” I don’t’ even know what to say about that line!

I wish the faults stopped there but even the main character was confusing. I never really knew what made Curtis tick – why he wanted to do this. There’s this vague reference to him being afraid to lead, but it was never explored or explained in a way that we could get behind. I mean at least Tanya had a clear motivation – she was trying to find her kid. Why does a secondary character have a clearer and stronger motivation than your hero?

To the writers’ credit, there were a few fun characters. Namgoong, our drug addict, was kind of fun in a slightly-more-dangerous Han Solo way. There were these badass twin villains that I liked. There was this huge beast guy who makes an appearance in an early battle. There were definitely moments where I could visualize a cool scene in the theater.

But see, there’s the trap that so many writer-directors fall into. They’re so focused on the visuals that they don’t make sure it works on the page first. And it’s gotta work on the page. Bong has an amazing visual sense. The Host showed that. But you gotta give us a story or none of the visuals will matter. That’s Storytelling 101.

If I were writing this, I’d make everything about the train a mystery. The guys in the back have no idea why they’ve been on this train since they were born. And one day they decide they want to know more. And they start fighting their way from car to car. With each car, they learn a new clue as to what this train is and what they’re doing on it. In other words, instead of knowing the whole backstory before we meet our characters, we’re learning what’s going on as our characters do. I think that mystery would make this story a lot more fun. At the end, they’d probably find out that they were food for the rich (cannibalism is already a part of the script – this would allow them to incorporate it more fully).

You’d then have to redo the entire mythology. Get rid of the weird global warming “so let’s build a train” stuff. I still don’t know why a never-stopping train would need to be built for any reason, but I’m sure if a dozen Scriptshadow folks brainstormed the idea for twenty minutes they could come up with 10 better reasons than this one.

Of course, it’s all too late for that. The script has been shot. The movie is wrapped. I just hope Bong fixed some of these issues in the meantime.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Play devil’s advocate with every idea you come up with, especially when you’re creating new worlds in sci-fi or fantasy scripts. Snowpiercer could’ve avoided so many plot holes if someone would’ve simply challenged its goofy ideas. “Why would someone build a train to keep people warm?” “If someone has an undying energy source in a freezing world, why are they using it on a train instead of as a heat source?” “If nobody can live outside, who’s maintaining the 30,000 miles of track the train is on?” “Do you really think that 20 years could pass without a single track maintenance problem?” Playing devil’s advocate ensures the script doesn’t cheat.

This is your chance to discuss the week’s amateur scripts, offered originally in the Scriptshadow newsletter. The primary goal for this discussion is to find out which script(s) is the best candidate for a future Amateur Friday review. The secondary goal is to keep things positive in the comments with constructive criticism.

Below are the scripts up for review, along with the download links. Want to receive the scripts early? Head over to the Contact page, e-mail us, and “Opt In” to the newsletter.

Happy reading!

TITLE: Swine’s Blood

GENRE: Crime/Drama

LOGLINE: A rookie detective must put aside his contempt for religion to tackle his first assignment, a serial killer who targets catholic priests

WHY YOU SHOULD READ (from writer): “Greetings! I’m just out of college and unemployed! So what do I do with my free time outside of job hunting? Well writing among other things, but more specifically screen writing. Now this is only my second script I’ve ever written and also my first draft. My first script isn’t what you would call… stellar, but I believe I’m really honing my skill and finding my voice in this craft. But perhaps another set of eyes can confirm or deny this illusion of mine. Thanks for your consideration!”

TITLE: Templar

LOGLINE: In order to save himself from an inquisition in 1307, a Templar knight must infiltrate a fortified citadel in the Holy Land to steal the Holy Chalice from a ruthless warlord.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ (from writer): “Templar recently made the Semifinals in the 2013 Bluecat Screenplay Competition.”

TITLE: Derelict

GENRE: Serial killer thriller/police drama

LOGLINE: As a ruthless serial killer terrorizes the city, an alcoholic cop turned psychotic bum scours its underbelly for the Holy Grail of designer drugs in a misguided attempt to clear his head for the sake of his troubled teenage daughter.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ (from writer): “This originated as a spec sequel to SE7EN and took on a life of its own after several rewrites and an option that went absolutely nowhere.”

TITLE: Redemption

GENRE: Action/Thriller

LOGLINE: An innocent young girl with a troubled past fights to survive murderous attempts on her life by the man who destroyed her family.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ (from writer): About the script: This script was originally written last year and sent for coverage where it received a pass. I followed the reviewer’s advice, did a full page-one rewrite. And, although I can’t give you their name, the script was read by a creative executive from a very reputable production house, as well as several of his readers, and he labeled it “great”. Unforeseen circumstances interceded, and our engagement ended. But not before he expressed his desire to work together in the future.

Will you give this script a chance to redeem itself?

TITLE: Beth Aven

GENRE: Supernatural horror.

LOGLINE: When an angelology professor and his wife lose their daughter to tragedy, they are invited to a mysterious retreat which promises communion with the dead. The cost? Only one of them will survive.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ (from writer): “A lean 87 pages, BETH AVEN is written for the $1 million / limited location model. In style and tone, it is THE BLAIR WITCH PROJECT meets THE EXORCISM OF EMILY ROSE. It is intensely character-driven, but delivers the actions and scares inherent to the genre. At its core it is the tale of parents who’ve lost their only child, and the harrowing journey to the gates of death that will mark their lives forever.”

Amateur Friday Submission Process: To submit your script for an Amateur Review, send in a PDF of your script, along with the title, genre, logline, and finally, something interesting about yourself and/or your script that you’d like us to post along with the script if it gets reviewed. Use my submission address please: Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Remember that your script will be posted. If you’re nervous about the effects of a bad review, feel free to use an alias name and/or title. It’s a good idea to resubmit every couple of weeks so your submission stays near the top.

Genre: Comedy

Premise: (from writers) In a last ditch effort to sell his screenplay, a self-absorbed writer kidnaps actor Kevin Bacon.

About: (from writers) Carson, according to our mothers, we’re a couple of sexy, cool screenwriters with a fun little screenplay. According to us, we think you’re going to enjoy reading TAKING BACON. Why? Well, for starters, we’re already getting attention from some of Hollywood’s biggest movers and shakers. Who you might ask? Do Steven Spielberg and J.J. Abrams ring a bell? (this was sarcasm by the way).

Writers: Michael Fitzgerald and Matt Carrier

Details: 104 pages

Whoa, Taking Bacon was hit with the controversial stamp in Amateur Offerings last week. There were a few comments praising the script in the comments section that sounded less like a critique and more like mom and dad giving approval.

Truth be told, I wasn’t bothered by any of it. I loved this idea and since there was no clear winner in that Amateur Offerings bunch, I figured why not go with the concept that had the highest upside. Granted, this kind of script depends on getting Kevin Bacon, but it’s not like he’s having to fight off fans these days.

I figured even if I didn’t like Taking Bacon, maybe I could offer the writers some ideas on how to get it into shape. Comedy is rarely executed well on the amateur level. The story’s almost always a mess. As I do before every comedy, I say a little prayer to the script gods that that won’t be the case this time. Please, I said, let Taking Bacon be different. Did the Gods listen??

Like most movie characters, 33 year old screenwriter Morgan Wright isn’t where he wants to be in life. As in he’s an assistant at a production company. Sure he’s got access to one of the top producers in town. But being that close to someone who can change your life is almost as worse as being light years away. I mean every day you’re staring at the man who, with the flick of his wrist, could have you writing the next Jurassic Park. Yet whenever you mention your script to him, he quickly changes the subject and disappears.

The sorta good news is that Morgan gets fired from that nightmare. The bad news is he walks in on his girlfriend playing naked sex-organ tickle with another man. And that’s the point where his life officially falls apart. Recent breakups and unemployment are never the condiments you want to spread on your life sandwich. The only thing that makes waking up bearable anymore is that his new friend, Darrel, a security guard wanna-be actor, is even more pathetic than he is.

But Darrel’s got a pretty sweet idea. He’s got this business associate down in Mexico with a lot of money. Why don’t they just go straight to him for some financing and make their own movie!? Problem with that is, this Breaking Bad extra lookalike wants a star. So Darrel offers up a white lie. He happens to say that his favorite actor, Kevin Bacon, (who he’s seen like 50 times in Wild Things, freeze-framing every time the Bacon full-frontal shot happens for reasons unbeknownst to anyone in the script) is attached. Going off this information, the shady Mexican businessman says, sure, bring him down here and let’s make a movie!

So the guys head down to Comic-Con where the Baconator is heavily promoting his next film – Hang Glider! It’s about a guy who hang-glides. They approach him about starring in Morgan’s current script (an alien musical) but he blows them off. Knowing this is their only shot at stardom, Darrel waits until Kevin Bacon goes to the bathroom and tasers him. Morgan’s freaked out about this turn of events, but Darrel convinces him that they can either get on the Success Train or stay at Failure Station forever. Morgan chooses train.

Together, the three head down to Mexico, where they encounter a major detour at a Native American reservation. In the meantime, Kevin Bacon’s agent desperately needs Kevin to sign the franchise papers for Hang Glider 2 and 3. So he goes after them. But not before they finally make it to Darrel’s money buddy, who promptly changes the rules as soon as they get there, a la Darth Vader in Cloud City. What’s going to happen to Kevin Bacon? What’s going to happen to poor little Morgan? And what about Doofus Darrel? You gotta read to find out folks!

Taking Bacon has that required professional polish that a comedy spec needs – it shines enough to say to others in the business, “I’m not a drive-by screenwriter. I know what I’m doing.” But as the story evolves, a lot of those frustrating craft/story holes you see in amateur scripts start popping up.

Let’s start with the premise. Regardless of how wacky your comedy premise is, when you set it up in your story, it needs to make sense. Taking Bacon is predicated on this notion that Kevin Bacon is a bankable movie star. He isn’t. He’s a fun topic of conversation. But nobody’s rushing out to see his movies. So right from the start, as they’re trying to get Kevin Bacon to be in this movie so they can get money, I’m thinking to myself, “Um, that doesn’t make sense.”

And if it doesn’t make sense to me, history tells me it isn’t going to make sense to a lot of other readers either. Not that I’d go this route, but if our main character was in love with Footloose and had written Footloose 2 – now it makes more sense why he has to kidnap Kevin Bacon. Again, I wouldn’t take that route. I’d sit down and brainstorm something with more depth. But the point is, it makes more sense for the setup. And the setup is the one part of your script you can’t have any holes in.

This brings me to Kevin Bacon himself. I’m not sure the writers have figured out what’s funny about Kevin Bacon. Because really, you could’ve inserted any faded movie star into this role and it would’ve been the exact same movie. That cannot be the case. If you’re going to pick a well-known person to make fun of, you better have a ton of specific jokes and situations that will make fun of him. If you’re doing a roast of Donald Trump, you don’t start making jokes about Simon Cowell. For example, say we exchanged Kevin Bacon for another faded star, like Hayden Christensen. You’d then stack your script with Star Wars prequel jokes and situations that would force Hayden to re-enact dumb Star Wars scenes.

There was just nothing specific to Kevin Bacon here. I know, for instance, that Kevin Bacon lost a fortune, almost his entire life savings, to Bernie Madoff. We could’ve exploited that for some jokes. But really, the most frustrating thing about Taking Bacon is it meandered around with no real purpose. I mean it did have a goal (get to Mexico to talk to the guy) but why, for instance, are we spending 30 pages at an Indian reservation? What do Indian Reservations have to do with Kevin Bacon?

When you come up with a premise, every scene should exploit that premise. In The Hangover, we don’t have a scene where they go have a trampoline showdown with a bunch of prostitutes. Not that a great comedy writer couldn’t make that scene funny, but it’s NOT RELEVANT to their situation. Their situation is that they don’t remember the previous night, and therefore must follow the trail of receipts they have to find Doug. Every time they do something, it’s an extension of that specific problem. I didn’t see that here. The Indian and Comic-Con stuff felt completely random.

Again, this comes back to, “What is it that’s funny about Kevin Bacon?” The one thing everyone always talks about is the six degrees stuff. Is there a story you could build around that? In order to get Kevin Bacon, they have to go through the six degrees of people they know between him? I don’t know, I’m just riffing here. But, without question, we need the comedy in this script to be less random and more relevant.

Now was the script funny? Comedy is so subjective, I’m not even sure if my answer matters. I’m thinking for any good comedy script, you gotta be laughing out loud at least 30-40 times. I laughed out loud maybe five times? Again, that’s just me. Doesn’t mean someone else wouldn’t die laughing. For me, Kevin Bacon getting bitten by a snake on his dick and then Morgan having to suck the venom out? Even though I was cringing the whole time, I have to admit I laughed.

I think for this script to work, the set-up has to make a lot more sense (you can’t just invent rules like “Kevin Bacon is a mega-movie star in my world”). On top of that, all the situations have to be more Kevin Bacon specific. Instead of thinking, “What kind of wacky situation can I put my characters in? Ooh, an Indian Reservation could be hilarious,” think “what situation would be the worst to put Kevin Bacon in right now?” Maybe they stumble upon the town where Footloose was filmed, and everyone there hates him for it because the entire world now associates their town with a bunch of dancing pansies. So they all want to kill Kevin Bacon. That kind of thing. If it’s not relevant and specific to the setup, it probably won’t be funny.

This is something every writer has to learn, usually the hard way, so hopefully Michael and Matt will take that to heart. ☺

Script link: Taking Bacon

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Remember that dick, poop, and ‘constant swearing’ humor is typically considered the cheapest humor out there. In other words, it doesn’t take a lot of thought to put it together. Therefore, most readers hate these kinds of scripts. They like their humor with a little more thought put into it. I’m not saying dick and poop aren’t funny when done right, but you definitely run a huge risk if that’s the majority of the humor in your script.

Many of you may remember that a couple of months ago, I fell in love with an amateur script called “Where Angels Die.” Since that time the writer, Alex Felix, has secured management at Energy and Station Three, and representation at CAA. I sat down with Alex in Culver City last week to interview him about how he got here. Yesterday was part 1 of the interview. Today is the second half. Enjoy!

SS: Okay, Let’s get to the good stuff. Where Angels Die is reviewed on the site–

AF: Should I order a vodka shot for this part? We are at a bar…

SS: [laughs] What happened after that? Everybody’s interested in the process of what happens once you write something good and the industry recognizes it. What happened with you?

AF: With me, I had the great review from you, which helped tremendously. You put the script in the spotlight for sure.

SS: You got a crazy email from me at like five in the morning I think.

AF: Yeah, [laughs] you had just eaten your blue cheese. It was more than a little strange getting that e-mail. As much as some people will say that you’re a polarizing figure, when you give a script a great review, everyone wants to read it. People can argue about how you go about things, but the cold hard fact is you give a script an impressive, everyone wants to know about it.

SS: I don’t know what you mean by this polarizing thing.

AF: [laughs] Getting into the story of what happened– I got contacted by a couple of producers, Brooklyn Weaver right off the bat. And Roy Lee. They wanted permission to send the script around town and I said, “Shit, I better get out to LA.”

SS: But you were planning on coming out here anyway, so it was–

AF: A catalyst, yeah. Like someone had taken a big can of gasoline…

So, I came out and I have a family friend, Eric Brown, who wrote Hemingway Boy, and who’s repped by Thomas Carter at Station 3, and the first bit of advice I’d gotten was get a good manager, someone you can trust, and when I met Thomas, everything clicked. I also met with Kailey Marsh who works there. They said they wanted to co-manage me, and we spoke about it to Brooklyn as well. And he and Kailey used to work together and have a long-standing history. And everybody just decided, let’s try it, let’s go for it, it was a divide and conquer mentality. Brooklyn has certain people he knows, Kailey has her own contacts, and Thomas is really big in the TV arena — and I also write TV. So what can I say, I’m ecstatic. I’ve got a team behind me, and as a new writer, coming out here, it’s a great feeling to have.

SS: Tell me how you went from getting managers to getting agents. Because getting agents at an agency like CAA is really hard unless you’re already working or have something lined up. I know people who have sold things before who can’t even get a call back from CAA.

AF: I think you’re right. But at the same time there is a trend moving towards where if an agent finds something that they just fall in love with, they’re willing to take a chance on you. There’s also competition to get up-and-coming talent. But yeah, my managers helped out tremendously getting me meetings, and every manager has relationships at certain agencies. With CAA in particular, Matt & Alexandra had both read the script separately and reached out.

SS: So Matt and Alexandra are your agents at CAA?

AF: Yeah. Apparently they were at lunch discussing, “Hey, have you read anything good lately,” and Matt said “Yeah there was actually one script I got my hands on and it was really different and I loved the writer’s voice and this and that” and then he told her and she said, “Wait! I just read that the other day and I loved it too!” so they decided to contact the managers and team up and that was really cool.

SS: I wonder how they came about it?

AF: I’m not sure which channel exactly.

SS: But that’s a good thing if you don’t know how they found it. It means people like it enough to keep sending it around.

AF: Right. I had also taken meetings at other agencies and a lot of it is connecting with who’s the most enthusiastic about the project and you as a writer but also who, when you look at the packaging agencies, the Big 4, you look at the talent pool they have access to and the type of stuff they’re able to put together so you take that into consideration as well.

SS: Did you meet with any smaller agents as well?

AF: Absolutely.

SS: Because everybody wants to know, when they have that opportunity, do you go with the big guy where you might get swallowed up, or do you go with the small guy, who you know is going to champion you 24/7?

AF: Well, I have the best of both worlds right now because Alexandra and Matt, though they’re industry pros, they were promoted to agent status at CAA within the past year or two and they’re basically young and hungry like myself. I think they’re both looking for talent/clients whose careers they can grow, and I was looking for agents I could grow with as well. I really couldn’t have asked for more and I’m extremely grateful.

SS: It’s really hard to sell a script, naked, without anything attached, these days. I’m sure that went into your thinking with signing with CAA bc they can package things. So what is the next step? What is the thinking now that you have a couple of agents at CAA? What do they do with it? How does that whole process work?

AF: So CAA obviously reps a ton of actors and directors. One thing a writer can do is send their agent a wish list of directors and actors repped at that agency, but I think Matt and Alexandra are gonna go out and try and package talent they think will be as enthusiastic about the project as themselves, but who are also the right fit. The hardest part for me and for a lot of writers doing this for the first time is kind of realizing that the baton has been handed off so to speak. Basically letting go of the project, having confidence in your team, realizing that it won’t all happen overnight. Packaging can take months, even when everything is firing on all cylinders. So, as the writer, I can sit around and worry… ‘Well what are they doing? Who are they sending to? What’s going on with it?’ And constantly emailing and being annoying. Or instead just checking in every couple of weeks and letting them do their thing. I did my part. Now they’re gonna do their part, and hopefully they come back with a couple of different packages they’re excited about. But at the end of the day, that’s what’s probably hardest for first timers and I’ve definitely been making an effort to temper that part of me, to step back. Because it’s your baby for so long. You care so much. But if you trust your agents and managers, you have to trust they’re going to approach the right people with it… either that or you risk annoying the hell out everybody (laughs).

SS: I’m always curious– and I don’t know if you’d know this– but I’m always curious because in a big agency like CAA, these younger agents that are representing you, they’re sort of fighting to make their way up as well. How much influence do they have to get it to somebody like Bradley Cooper or somebody like, a big director who’s there? I’m always curious can they just do that? Or is CAA like, ‘No, you guys aren’t big enough yet.”

AF: Not at all. From my understanding, agencies, and CAA specifically, is very team oriented. They have several team meetings per week with all the agents where they discuss new projects and new clients and it doesn’t matter if the agent was just promoted last year or has been an agent for 20 yrs. Everybody goes to these meetings and they’re basically spit-balling different ideas back and forth and with any agent at any agency, everybody’s got A) their clients on their mind and B) the success of the agency as a whole. So to answer that question, any agent at CAA is going to have access to all of CAA’s talent pool. It’s a team effort. It’s their mission at the end of the day, so if a great project comes together, that positive momentum affects everyone, it’s a win for everyone. You sometimes even hear about agencies reaching across the aisle (to another agency) and if there’s one director they really want for a project but they rep the writer, you might even hear about that happening. It’s not as common, but it happens.

SS: You’ve done all that you can do on your end with Angels and now they’re sort of carrying the torch and trying to figure that out– what do you do in the mean time?

AF: The thing to do so you don’t go crazy is to keep writing.

SS: You’ve met a bunch of industry people through this process. Are you pitching these people? Are you pitching every time you go out? How do you approach that?

AF: Yeah, you have to be tasteful about it, though. You never want to go in there and make the hard sell. It usually comes up casually near the end when the meeting is– at some point it’s gonna come up, ‘So! what’s in the cards now?’ You then kind of let them know a couple things you’re working on that you’re excited about. Obviously discuss it with your managers first and get the okay. But everyone wants to know you’re prolific and you’re not just going to say “well, I’ve got something that’s getting tons of traction so that’s money in the bank so why don’t I just go to the beach or party it up.’

SS: Have you been to the beach yet?

AF: Once and it was raining [laughs]. It started raining right when I got there. After I’d paid like $15 for parking, in my bathing suit, with my buddy, so yeah, beach and rain clouds. Definitely picked the wrong day. I’ve honestly been holed up writing at Barney’s Beanery or my apartment or whatever Starbucks I see as I’m driving. Those have been the main locations.

SS: Barney’s is like, where you go to get wasted.

AF: I like it during the day, when it’s not busy, in a corner booth. The chili is ridiculous.

[15 minute conversation about chili and food in general removed]

SS: So where are you living again?

AF: I’m living mid-city now. I don’t even know what that means.

[laughs]

SS: I don’t know what that means, either. Every time you’ve said that I’ve thought to myself, “What is he talking about?”

[laughing]

SS: What’s next? I know you can’t talk about specifics but let’s talk about specifics.

AF: [laughs] Yeah so there’s an original TV idea that my managers helped me sharpen that we’re working on right now and that’s another cool thing about having managers is you can send them ideas and log lines and you’ll see which ones they like. Trial by fire. That’s what’s great about having a team behind you. You see which ones they latch onto. After all, they’re in the business, they know what to look for. As far as the TV show, I’m working on that with a writing partner – a close friend I’ve been collaborating with for years on different projects. There are also two features in the works.

SS: I know you can’t give me the concept for the TV show but what about the premise and summary?

AF: [laughs] I can’t, sorry.

SS: I see. No problem. Hmmm, maybe you can tell me what it’s like then? Is it like, for example, Breaking bad?

AF: I could tell you it’s dark and gritty? I wish I could tell ya more, trust me. Hopefully you’ll be hearing about it through the appropriate channels soon.

SS: Now, speaking of that, what is the next step with your TV pilot as far as pitching it? Cause there’s this whole seasonal thing with pitching that I don’t understand.

AF: You’ve got your broadcast networks and you’ve got cable. Cable you can pitch year round and I think pitching season for broadcast networks kinda wraps up around the end of November.

SS: So when did it start?

AF: I don’t know to be honest.

SS: But it’s going on right now?

AF: Yeah. And then for cable it’s year round and so, it just matters the type of show you’re trying to do. But really if you’re linked up with people who work in the TV space and the concept’s original and it lends itself to your voice and you know you’ve built a cool world and characters people care about, definitely right now with TV, people are buying. I would encourage writers who have only ever done features to maybe give the TV thing a shot.

SS: I’ve been seeing TV in a whole new light. It just seems exciting. I don’t understand it as much, so I feel like there’s a lot more to learn.

AF: Well, what’s cool about TV is it’s very character-driven.

SS: Right.

AF: You really get to know the characters. If you watch a show for six seasons, one of my managers brought this up, while he was re-watching the Sopranos, he spent more time with Tony Soprano and Paulie Walnuts than some of his real friends. It’s also a challenge, because aside from the characters having to be really on point, it’s not just this neat little package with a beginning, a middle, and an end, it’s “What’s next?” “What’s next season?” “What new characters are we bringing in?” “What characters are we killing off?” I think it’s a great way for writers to challenge themselves. I would tell everybody on SS who has never tried TV – I just don’t see how trying it could hurt. It makes you more versatile.

SS: I have to meet with my parole officer in a few minutes. Any last bit of wisdom for aspiring screenwriters?

AF: From my story, don’t give up. Literally, just don’t give up and that sounds super cliche but for me it really hits home. And continue to digest and read as much as possible, as many scripts as you can. I mean, I honestly read the site every day this isn’t just a plug for SS, but whether it’s your site or a different site you like that’s educational. Write as much as possible. Also don’t be afraid to open yourself up to working with other people and getting feedback from other people. All that good stuff.

Many of you may remember that a couple of months ago, I fell in love with an amateur script called “Where Angels Die.” I liked it so much, I put it in my top 10. Since that time, the writer, Alex Felix, has moved to Los Angeles, garnered co-management from Energy and Station Three, and secured representation at CAA. The agency is currently packaging the material to go out to studios with. I sat down with Alex in Culver City last week to interview him about how he got here. The interview went a lot longer than expected so I’m going to split it into two parts. Part 1 is today and Part 2 will be posted tomorrow. Enjoy!

SS: When did you start writing?

AF: I’ve been doing it for 8 years now, so since 2005.

SS: I think you said you originally started writing short stories, right?

AF: No, well, the first thing I wrote was actually a novel.

SS: Exactly. I totally knew that.

AF: Yeah. And so I sent it to some friends and they were like, “Oh, that’s cool.” I’m sure it was terrible. But I had always been fascinated by movies, so I thought, “Lemme check out screenplays,” and I started buying screenwriting books — I read Save the Cat a bunch of times. When you’re a beginner, it’s probably the best book you could read. People will argue that. But yeah, I read every screenwriting book I could get my hands on, and then I adapted that first novel into a screenplay, then wrote a bunch more.

SS: A bunch more screenplays?

AF: Yeah. And some of them were, y’know, eighty percent done or so and I’d be like, “Wait…”– I didn’t quite know what I was doing yet. Second act, black-hole type phenomenon. But eventually you push through and you push through and you keep doing it and, I guess what helped out, too, was working for Sniper Twins as a director’s assistant. I helped a lot with their pitch decks and longer form treatments. Working with Dax and Barry allowed me see scripted material from a director’s POV, which is something a lot of screenwriters don’t think about.

SS: Wait, who are these people?

AF: Sniper Twins? They’re commercial directors based in NYC, repped by Smuggler. You should check their stuff out, they’re really talented guys.

SS: This is just so not fair. I work with guys named “Daisy” and “Wheelchair Al.” You work with the “Sniper Twins.”

AF: What can I say? I’ve been lucky here and there.

SS: And what’s a ‘pitch deck?’ I want one for Christmas.

AF: Let’s say Nike has a concept for a commercial — they’ll basically take submissions from different repped directors, and it’s basically their version of how they would shoot the commercial. It’s kind of like a show bible but for a commercial, so it’s more visual. So, I helped [the Sniper twins] with that.

SS: So do they include storyboards?

AF: No, not really. For instance, you might include actor references, but it’s really about the look, the feel, the tone, and the world. That actually helped me with the world-building aspect of screenwriting, too, and seeing things visually. I learned a lot. And that’s when I went to film school.

SS: Where’d you go to film school?

AF: Digital Film Academy. It’s in New York. It’s not one of the expensive 4 year programs or anything, but they have a solid curriculum and everything is very hands-on. I’d been writing for a while by then, and what was cool about that was I got to write a bunch of shorts—for your thesis you had to direct your own short. I had never really messed with shorts before and so that was cool, too.

SS: Was your education just focused on the filmmaking side or did you write any screenplays there?

AF: I did, actually. I wrote three shorts while I was there and ended up picking the one I liked best and using that as the one to direct, but I was still working on my own feature-length screenplays on the side.

SS: So you finished there. Did you keep trying to direct or did you focus on writing?

AF: I focused on writing. I wanted to do the film school thing because I’d been writing a while, but wanted to explore all aspects of filmmaking. I did really like the process of directing, though. I think I had a 7D at the time and enjoyed DP’ing as well. I was doing the whole DSLR, run-n-gun, do-it-yourself filmmaking thing, but my passion throughout had always been the writing (that’s not to say I wouldn’t be interested in directing some of my own work in the future).

SS: It’s one of the best ways to get in the business, really, getting established as a writer, then when you write something everybody likes, hold them hostage: “If you want this made, I’m gonna be the director.” You can’t really do that at first.

AF: Yeah, I actually just spoke to Chris Sparling recently, great guy. He originally tried directing Buried after he wrote it.

SS: Yeah, that’s right, he wanted to direct that.

AF: That’s what he’s doing right now, directing his own first feature. I couldn’t be happier for him.

SS: Oh, he’s officially doing it?

AF: Yeah. You see that happening a lot more – writers who have written 3, 4, 5 screenplays, garner a lot of acclaim as far as their voice and their writing and saying, “I want to direct this.” Whether it’s using the contacts they’ve built up or “holding the material hostage”, as you put it.

SS: Yeah, that’s how I like to do it.

AF: [laughs] Well, those were your words!

SS: So, how did we get from there to Where Angels Die? How many scripts did you write in between? And how many years would that have been?

AF: I was in New York for six and a half years and I was writing that whole time. Where Angels Die was written afterwards, in Michigan. The plan was to move from New York to LA, but there was an extended pit stop in Detroit, which actually served the screenplay really well because I was in Detroit to write it. I think I had written about 6 features total before Where Angels Die.

SS: From the beginning?

AF: Yeah, not including the shorts and the novel.

SS: You told me you didn’t feel as confident in those previous scripts. Can you elaborate on that?

AF: Practice really does make perfect. Each time I look back at one of them, I see that I learned something, even just from script to script. And I would tell this to a lot of writers, when you write something you think is really great and you’re in your “cooling off period”, always put it aside for a few weeks. Don’t look at it. Instead, look at the last one you wrote, or even the one before that, and so many things will pop out at you, just from the experience of writing this new one. You might see characters in a completely different light, or that your dialogue is flat in places… and when you go back to the newer one, you see noticeable improvement. For me, the bar has been set at Where Angels Die—it’s not that I’m not proud of those previous efforts. Without them, I wouldn’t have gotten to where I am now. But would I send those to producers around town? I think they’re more interested in what comes next. And there’s already two, three things in the works.

SS: What was it about Angels that put it above your previous screenplays in your opinion?

AF: I knew this one was unique from the start. I had never written a screenplay in the city I was living in at the current time so I got to go location scout. As I was planning to write certain scenes I had the ability to visit those locations. With the Ambassador Bridge, for instance, I got to drive by that. When you have a picture in your mind– and this is also why, going back, directing and film school helps because when you’ve done that and you can visualize what the end product needs to look like, you know whether the scene works or whether there’s a good chance the director is just going to cut it. Those factors added depth, as far as the world building went. I think it was also just building on previous experience… something clicked for me. The phase of my own life I was going through, that probably influenced it as well — I was in, honestly, a little bit of a darker, moodier, depressing place. My plan was to drive from NY to LA and I had bought a POS early model Honda Prelude and so it ended up breaking down in the best place possible, in Detroit, because I have a lot of friends and family there. As I was there, I was writing and it was a setback, I didn’t have money to just go buy another car right away, also I was kind of, “Okay well, maybe it’s not meant to work out.” I still was going to keep writing, I never stopped, but you know how it is when you’re back home. My folks were really pushing me to…

SS: … to do stuff that actually paid money?

AF: Exactly. [laughs] So while I was in MI, I was just trying to keep everybody happy. Then winter came. It was a brutal winter and part of me was obviously depressed, although I don’t think I’d admit it back then– a part of me really wanted to go out to LA and follow my dreams. So I think that that unique mindset, it kind of lit a fire in me and there were at least 3 days in a row where I was banging out 10-15 pages a day and it was almost like this act of rebellion. So it was very personal and real to me and it was almost like I had something to prove to the world. I was angry inside and I dunno, writing was my therapy.

SS: I felt some of that anger in the script!

AF: Yeah! So, it was probably a combination of lots of factors.

SS: Something I really liked about Angels were the characters. I was curious how you approached creating characters.

AF: Well the first thing I always do – before I even approach the characters – is I’ll get the concept down. I’ll do some abstract brainstorming, a page or two of jotting down whatever ideas I have for this film, and then I’ll whip up a quick Blake Snyder, I’ll get those 15 beats down.

SS: So you actually use the Blake Snyder beat-sheet?

AF: Absolutely. Every time. I get my 15 beats down and then I’ll go and do my 40 scenes. So I’ll go in and for me it’s easier and I’m gonna get to character in a second – but this is just my process– before I even get into the characters I need to know what happens.

SS: So you’re more plot-centric when you start?

AF: Yeah, and that’s not to say there’s a right way or a wrong way. It’s just the approach that works for me. And sometimes I actually try and get my writing buddies involved early on, even in the outline phase, to get some feedback.

SS: So you’re actually sending out–

AF: It’s like when Blake Snyder says bounce your loglines off friends. I have a couple of close friends who’ve also been writing a long time and I trust their feedback so before I put TOO much effort into something I’ll ask what they think about the concept. So when I’m confident I have a great premise, I’ll write my 15 Blake Snyder beats, then flesh it out and get my 40 scenes down. Once I’ve got a good handle on plot, then I’ll go in and work on my characters. There was actually a Scriptshadow article that really helped me as I was developing my process. The one about the X-factor?

SS: I think the one about the 13 most important things every script should have?

AF: Yeah, that one and also the GSU one. Goals, stakes and urgency lend themselves to all the genres I write. So I make sure those are there. But once I know where the story’s going, I get to the characters. And I really start by making sure the characters aren’t stock, aren’t stereotypes.

SS: Well how do you do that? How do you make sure they’re not stock?

AF: I’m not sure if part of it is because I’ve always been more of a sociable person, and part of it is noticing little quirks about people in my real life. Someone I meet or know might have this really cool quality about him or her that’s intriguing and different. I kind of just keep those things in mind and if you base your characters in a bit of reality, then you know that A) they’re not gonna be way over-the-top or unbelievable, but B) they’re gonna have some qualities you’d find exceptional and different. It’s not the whole “give every character a limp and an eye-patch” thing, you could do that, you could make a list of ten things that sets this person apart. But for me, when it’s personal and it’s based off someone in real life, even just taking my own good friends and family, everybody’s got flaws, including myself.

SS: Which friend was placed into the cross-dressing killer role in your script?

AF: [laughs] It’s not only real life, it’s also movies you’ve seen. You just draw from all experiences, let’s see, Horatio was– I know a couple people who have really short tempers, actually, but keep in mind villains have to serve the protagonist, so you know Parker, being strapped all the time, I wanted someone who’s gonna make you really worry about Parker’s safety. Someone really unpredictable. I also have people in my life who’ve died of AIDS and so that was an influence in that decision. People kind of avoid that topic, which I get, but at the same time it’s a fact that a lot of inner-city prisoners are HIV positive, so that goes back to basing your character in reality in certain aspects. Even the medications he takes, I was working at a pharmacy at the time, so even that little part, write what you know. And then there were a few of the more standard villain tropes. There was also definitely a little bit of Heath Ledger’s Joker in there. I kind of built a Frankenstein villain that works for the story. I know one of the things you said was he was a little too over-the-top at times but you just don’t care because he’s unpredictable, which was what I was going for.

SS: So, obviously when you talk about character, you move naturally into dialogue, and one of the dialogue scenes I liked best was the scene where Parker yells at his co-worker. If felt so real. How do you approach dialogue so it feels natural?

AF: This is one of those things where going back to the older scripts you’ll notice huge improvements. When I go back to my earlier efforts, a lot of the dialogue is very on-the-nose. So that is probably, for me, that took the longest to lock in. How do I approach it? They always say to have actors read your stuff if possible. I’ve never had that opportunity, and writers who have are definitely lucky. I’m not hanging out with the cast of Breaking Bad on the weekends. For me, the dialogue has to serve the character first and foremost and also, I really at this point make a conscious effort (and this doesn’t come until 2-3 drafts in) to make dialogue NOT on-the-nose, to use subtext. Real people talk in short clipped sentences, they’ll cut each other off, they’ll be sarcastic. The better you know your characters, the better their dialogue is going to sound. Even just when you sit at a bar and people watch, you’ll notice there’s definitely a rhythm to the way people talk, and some people talk with their whole body while others are very conscious of how they come across. The main thing I would say is really do everything you can to make sure your characters are not just conveying information that you want your audience to know. No one wants to sit around and read that. If you’re giving notes on an amateur script, bad dialogue will be one of the first things you probably notice.

SS: Right.

AF: It’s the quickest way to sink a script. I’ve seen people who can write great action scenes, great description, and then you get to the dialogue and it’s like, “God, none of these people sound like real people.” So yeah, that’s what, I think for me, took the longest to nail down. Other writers are naturals at dialogue. For them other aspects of the craft are harder to pick up (like structure). But this is how the world works for me.

Part 2 of the interview is here!