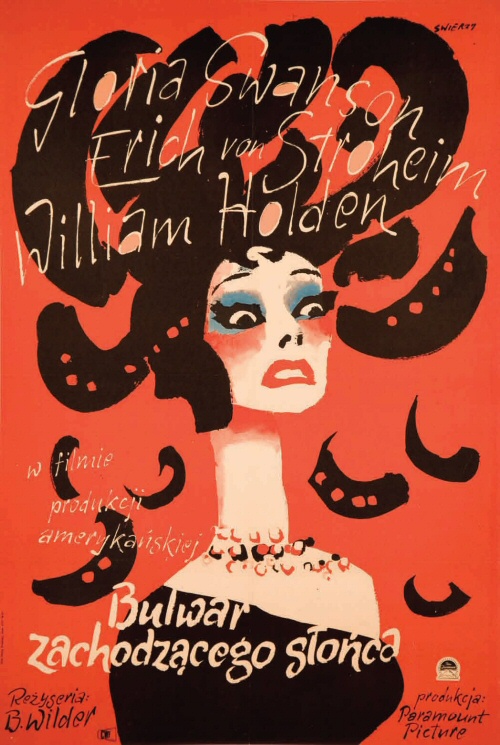

So, a dozen years ago, I said to myself, “If I’m really going to understand this industry, if I’m to be as knowledgeable in cinema-speak as everyone I run into, I’m going to have to watch every good movie ever made, even the ones I have no interest in seeing.” Which was a big problem for me because I didn’t like black and white films. They were all so over-acted and the lack of color instantly dated them, making it hard to fully immerse myself in the experience. People knock me on this, but movies are about suspension of disbelief. If at any point that suspension is broken, so is the magical movie spell. And black and white breaks the spell for someone who grew up in color. But I felt I owed it to myself to see all these movies, so I did. Outside of Hitchcock’s films and a few others, Sunset Boulevard is the only black and white movie where I forgot the black and white. There was something about the film, despite it being 50 years old, that felt so current. I’d never seen that with these old movies before. I’ve been aching to revisit it forever and “Ten Tips” seemed the perfect motivation. For those who haven’t seen the film, it’s about a down-on-his-luck screenwriter who accidentally befriends a washed-up silent film actress. I highly recommend seeing it if you haven’t yet.

1) Myth: You can’t write a movie about Hollywood – I used to believe this myth. But the truth is, you just can’t write a BAD movie about Hollywood. It doesn’t matter what the subject matter is. If you have great characters, a unique concept, a compelling plot, nice twists and turns, nobody’s going to say to you, “I thought your script was the best I’ve read all year. But I have no interest in it because it’s about Hollywood.” If something is good, people WILL WANT IT. I think the key to the “about Hollywood” script is the concept. Focus on something less obvious than your basic “screenwriter/actor trying to make it” storyline. Sunset Boulevard is about a struggling screenwriter who gets kidnaped into a fading actress’s house of horrors. It dealt with Hollywood from a different perspective. If this is had been about our hero, Joe Gillis, trying to get his movie made, Sunset Boulevard would have been forgotten two weeks after it came out.

2) Timeless movies are driven by characters with universal problems – The question I’ve constantly asked myself about this film is, “How come this 60 year old film still feels relevant today?” What is it that makes any movie stand the test of time? And I’ve come to the conclusion that it’s timeless characters – characters with universal problems that people are going to have today as well as have a hundred years from now. Norma Desmond is terrified of being alone. Joe Gillis is struggling to make ends meet. Betty Schaefer doesn’t know if she should be with the “right” man or the man she’s in love with. Give your characters relatable universal problems and they’ll last for ages.

3) Don’t expect a great movie unless you have a great character – The more I read, the more I realize that you shouldn’t even bother writing a movie unless you have a REALLY INTERESTING, UNIQUE, MEMORABLE character SOMEWHERE in your script. Those are always the scripts that actors are most interested in. Those are always the scripts that get made into movies first. Those always turn into the films you remember most. Sunset Boulevard is Sunset Boulevard because of the wacky crazy antics of Norma Desmond. The woman has a chimpanzee buried when we first meet her! What interesting shit does your character do?

4) Interesting characters tend to be supporting characters – Although I’ve seen movies with really wacky main characters, most of the time, the memorable characters are not the hero. Why? Because the hero has to be the straight man. He has to be the one to keep the story on track. He must be grounded. If he’s too wacky, the story becomes unfocused and messy. Jack Sparrow, Han Solo, Quint, Doc from Back To The Future, Norma Desmond. Supporting characters tend to work best in those secondary roles because they can be wacky without upsetting the balance of the story.

5) The intruding storyline – Remember that whatever your story is about, you want to have an “intruding” storyline, something that’s trying to make its way into your character’s life independent of the main plot. At first, in Sunset Boulevard, it’s the repo men. They’re constantly on Joe’s trail. They’re coming to Norma’s house. You need this intruding storyline because if all you have is your main plot, the script’s going to feel thin.

6) If an intruding storyline ends, replace it with another – This is where the real writers show their mettle. They know that certain subplots are going to conclude in the middle of the script, and when that happens, they need to replace them. So here, the intruding storyline of the repo men ends. What’s going to replace it? Wilder and his crew write in the Betty Schaefer screenwriting plotline, which intrudes bigtime on the main plot (and ultimately ends up in Joe’s demise!). You always want at least one story element intruding on the main plot, and probably more.

7) Great lines of dialogue tend to stem from character – “I am big. It was the pictures that got small,” is one of the most famous lines of dialogue in history. I spend entire nights, sometimes, trying to figure out what makes a great movie line. I still haven’t figured out any definitive formula, but Sunset Boulevard reinforced one of my beliefs: The best lines of dialogue stem from character. Norma Desmond is a narcissistic, delusional fame-whore who erroneously believes she’s still a star. Naturally then, when someone says “You used to be big,” she’s going to give a narcissistic, delusional fame-whore-like response: “I am big. It was the pictures that got small.” So when looking for that amazing line, start by asking who your character is.

8) CONFLICT ALERT – Remember that nearly every scene you write should have some element of conflict in it. Take a very simple dance scene in Sunset Boulevard. Norma Desmond has a “party” which she of course invites Joe to. When he gets there, there are no other guests. Just him. She then wants to dance. Joe does so, but reluctantly. The scene then revolves around this simple setup: She wants to dance, he doesn’t. You can see this dynamic extrapolated over the entire movie. Almost everything in Sunset Boulevard is about Norma wanting something and Joe not wanting it. This is the conflict that drives every scene, and by extension, the film.

9) Contrast the surrounding elements with the moment at hand – In that same scene, Joe and Norma get into a fight. The ugly battle is contrasted against the beautiful music from the live band. Contrasting the surroundings with what’s going on with the characters is always good for a scene or two in your script.

10) The Anti-Love Story – I’ve found that these “anti-love” stories are almost always interesting. By “anti” I mean a love story where one or both of the characters doesn’t want the relationship, but are stuck in it anyway. Movies like 500 Days of Summer, The Break-Up, War of the Roses, Sunset Boulevard. We’ve seen every love story in the book, which is why they all feel so cliché. Anti-love stories are much rarer, which is why they tend to be so fascinating when done well.

Genre: Sci-fi

Premise: (from IMDB) Set in the year 2154, where the very wealthy live on a man-made space station while the rest of the population resides on a ruined Earth, a man takes on a mission that could bring equality to the polarized worlds.

About: This is Neill Blomkamp’s second feature film. Blomkamp came to prominence when Peter Jackson surprisingly picked him for the gigantic task of directing the Halo movie, at the time the biggest project in Hollywood. That film fell through, but not to worry. Blomkamp would go on to direct the sleeper hit, District 9. He’s since been courted by just about everyone, all of them wanting him to direct their films. But Blomkamp has said he’s only interested in making his own stuff, which is why he went off and made this movie. However, Blomkamp is definitely playing with more money here (and a bigger star) so the pressure is much bigger this time around. The film finished #1 at the box office this weekend with 30 million, which is good. But it is 8 million less than District 9 opened with three years ago. Whereas with D9, Blomkamp co-wrote the film with writer Terri Tatchell, he went it alone on Elysium. Blomkamp is already hard at work on his next project, Chappie, which is said to be a sci-fi comedy.

Writer: Neill Blomkamp

Details: 109 minutes (119 pages)

I love Neill Blomkamp. I want to swap cameras with him. I want to hang out all day on set with him and share a laugh when something goes wrong. I want him to say, “Hey Carson, where are you sitting,” when it’s lunchtime, then follow me to my table. He’ll then ask me, “What did you think about that shot, Carz?” “It was good, Neill,” I’d say, “But you probably could’ve gone a little lower with the angle.” “Jiminy Wax, Carz, that’s exactly what I was thinking. You should be directing these movies. Not me.” “Aww, stop it, Neill. You’re just saying that.” Yeah, I’m a little bit creepy when it comes to Neill Blomkamp, I admit it.

Which is why my Elysium experience was so confusing. It started out great. Matt Damon’s walking through a gritty, ugly futuristic Los Angeles. Robot police are roughing him up. Mood-stabilizing pills are spat out at you if you look even mildly depressed. It’s exactly what I see 2152 looking like. For a good 15 minutes, I was thinking: “This is it. This is his masterpiece. As of this moment, I’m marking this as genius.” There is nobody, right now, who creates a more honest and interesting futuristic world than Neill Blomkamp.

But then little choices here and there began to bother me. Before I get into those though, here’s a quick summary of the story: So there’s this guy, Max (played by Matt Damon) who lives in the slums of LA in the 22nd century. Everybody is poor here. Everyone is struggling. We’ve ripped our planet apart and turned it into one giant trash-bin (without the lavender-scented trash bags).

One of the only ways to make it in a world like this is crime. Which is exactly what Max did for awhile. But now he wants to leave that world. He wants to earn an honest living (likability alert – We like characters who are trying to turn their life around!). But one day at his factory job, a mishap leads to him getting severe radiation poisoning. Which means Max will be dead within five days.

There’s only one way to survive a disease of this magnitude. Get to Elysium. Elysium is a giant space station that houses only the rich people. Realizing the earth was fucked a long time ago, the richies built this utopia for themselves so they could play polo whenever they wanted and build castles for their pets. Oh, and because all these people are so damn rich and it’s the future, they have these MRI like machines that instantly cure them of any disease.

Unfortunately, getting to Elysium requires knowing a person or two, and to hitch a ride, Max will have to do one last job (a data heist). What he doesn’t know is that the heist gives him super sensitive information about an impending coup up on Elysium. Which means that just about everyone with a gun wants a piece of him. This leads to the inevitable question: Can Matt Damon save the world!?

Elysium was over-themed. The theme of this movie was brought up every two minutes, I swear. The poor are fucked. The rich are set. And it’s not fair. This is explored mainly through the fact that if poor people get sick, they die. If rich people get sick, they cure themselves.

Which is fine. It’s important to explore a theme in your script. But we’re just bombarded with this theme throughout the screenplay. A woman escapes onto Elysium, runs her daughter to a medic-machine. It cures her. Matt Damon gets sick. He’s told he’s dead in 5 days. We meet the romantic interest, a nurse, who has a daughter who’s dying of cancer. We have shots inside the hospital of hundreds of minorities dying. Then we have shots of the city, where everyone looks sick and diseased. (spoiler) Then we get the ending, with all the smiling, happy, running kids laughing as their feet splash through the water on their way to the newly distributed medical machines. It’s laid on REALLY thick.

One of the most important things about writing is to be invisible. Whatever you’re pushing, whether it be a setup to a later payoff, a plot twist, a theme, an act break – The audience (or reader) must never know that that’s what you’re doing. They should never think of the writer writing his plot twist or his theme. All of that stuff must feel invisible. Therefore, if you’re sloppy with any of these things or push them too hard, it becomes obvious to the audience what you’re doing and they check out.

What complicates this is that each person is different. Person A might need you to mention your theme four times before they get it while Person B might only need you to mention it twice. It’s why you can’t please all the people all the time. No matter what you do, someone’s always going to say there was “not enough” while someone else will say there was “too much.” So figuring out that balance is always one of the hardest things about writing.

But I just felt Blomkamp got out of hand here. By the end, it was like, “We get it! This is like the Mexico border! Rich Americans have health care. Poor people don’t.” I wish he would’ve played around with the plot more and gone with something a little less on-the-nose.

In addition to this, the script gears had to work way too hard to keep the plot moving. There seemed to be four storylines. Max getting radiation poisoning. The Nurse and her dying daughter. Jodie Foster’s secret coup. And bad guy Agent Kruger. Getting to a point where Matt Damon ALONG with the bad guy would be going up to Elysium WITH this little girl so Max could save her felt like every plot gear on the planet was grinding to make it happen. I could see fingers typing: “Okay, we need to get Max to the nurse’s apartment so Kruger can track them there, take them, use them as bait to draw Max in, then also have Spider set up the reboot process on Elysium since the girl doesn’t have citizenship on Elysium and therefore won’t be accepted by the machines…”

It felt more like a writer trying to find his way to his destination than a smooth, natural story. That clunkiness is something you can only solve with tons of rewrites.

I also had a couple more issues. Agent Kruger, our villain, felt very… cliché. He was just this angry dude. There was no subtlety to him. There was no motivation behind his actions. He was just your garden-variety, crazy, loud, angry villain. Those kinds of characters are fun to play, I’m sure. But I couldn’t even begin to tell you why Kruger was the way he was. Why he had weird metal things in his skin. Why he randomly carried around a samurai sword in the year 2152. Why he gets mad when his face regeneration makes him more handsome. Villains need to be original and make sense. I didn’t get either of those from this character.

And finally, I was so confused by Max’s suit! I thought it was going to turn him into superman. That thing was splashed all over the posters and trailers and for good reason. It looked awesome! So imagine my disappointment when it only made him… a teensy-tiny bit stronger. In fact, there were times where I didn’t even know if it made him stronger. There was this whole unclear, complicated thing with his medication that made him weak. So he was weak from the radiation and medication. But the suit made him strong. So did those two things cancel each other out and just make him regular strength?? The rules of the universe weren’t clear. And that’s one of the first things you gotta get right in sci-fi. The rules of your universe MUST BE CLEAR (that’s one of the reasons Matrix was so good. They worked hard to make sure you understood the rules).

Now it may sound like I hated Elysium. But I didn’t! No amount of writing quibbles could undermine the awesomeness of this world Blomkamp created. It just looked so damn real. I mean, I see those fucking robots policing our streets someday for sure. I see future Los Angeles looking EXACTLY like that.

The story also had a really strong pull to it – Elysium itself! Despite the clunky plot elements, I WANTED them to get to Elysium badly. I wanted to see that awesome spinning wheel and the outrageous mansions and the outright beauty of this artificial world. Also, because the CHARACTERS wanted to get there so badly, I wanted to get there badly. I’m a sucker for a big goal with high stakes and Elysium’s got that (the main character’s dying and must get somewhere to save his life!). It kept us interested until the end. Still, this was a much better movie than script. Neill’s cinematic vision saved a screenplay that probably needed 4-5 more drafts.

Script rating:

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

Movie rating:

[ ] what the hell did I just see?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the price of admission

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: The early drafts are where you figure out the logistics of your plot. The rewrites are where you smooth those logistics out. If you stop 4-5 rewrites short, your plot’s going to feel that way. It’s going to feel mechanical and “written.” Keep rewriting until your entire story feels effortless.

This is your chance to discuss the week’s amateur scripts, offered originally in the Scriptshadow newsletter. The primary goal for this discussion is to find out which script(s) is the best candidate for a future Amateur Friday review. The secondary goal is to keep things positive in the comments with constructive criticism.

Below are the scripts up for review, along with the download links. Want to receive the scripts early? Head over to the Contact page, e-mail us, and “Opt In” to the newsletter.

Happy reading!

TITLE: Dead Woman Walking Free

GENRE: Drama/Suspense

LOGLINE: A teacher’s obsession with a boy who is the spitting image of her recently-deceased son escalates into a deadly confrontation with the boy’s mother – a former midwife with a dark secret.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ (from writer): “You’ve been complaining lately about writers ‘rehashing their favorite movies in one form or another, copying their favorite writer’s style, instead of looking for new ideas and telling stories in new ways.’ Point taken. Dead Woman Walking Free attempts something different. You be the judge of it.”

TITLE: The Twin

GENRE: Crime, Thriller

LOGLINE: After looting one of two priceless statuettes known as the Twins in Iraq, a couple of down-on-their-luck veterans must traverse the U.S. criminal underworld on a quest to sell it — not realizing that the owner of the other Twin is a high-ranking intelligence official who will stop at nothing to get his hands on their statue.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ (from writer): “Ever since uploading my short “J-W-G” at the tail end of Shorts Week, I’ve been fielding a surprising number of requests from ScriptShadow readers for a feature-length script of mine. So here it is — a classic crime road movie in the vein of “True Romance” or the original “Getaway.” I don’t think there was a single decent example of the subgenre written in the 2000s, let alone in the 2010s.”

TITLE: CROSSFIRE.pdf)

GENRE: Action/thriller

LOGLINE: A thief discovers a mysterious girl in the trunk of a stolen car and must help her escape from a relentless pursuer who wants her dead.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ (from writer): “I’ve flirted with success but haven’t quite been able to get over the hump. I had a short stint with The Onion News Network. Placed in the 2011 PAGE Awards. Landed a low-level manager. The PAGE winning script went out to the town and did absolutely nothing – no sale, no option, no meetings – which crushed me because I thought I was ready when I was still a long way off. It took me a long time to pick myself back up off the floor and start writing again, but here I am — better than before but wondering if I’m better enough.”

TITLE: Soul Catcher

GENRE: Horror, Supernatural, Thriller

LOGLINE: A wayward priest hunts menacing souls by exploiting a woman in a constant vegetative state. The woman serves as an empty vessel for spirit possession but morality is questioned when she becomes conscious and aware.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ (from writer): “This story plays out like a more serious version of Ghostbusters. In addition, the Soul Catcher role would be a challenging part for an actress to play with all the different spirit possession characters. Finally, exorcism/horror scripts are typically easier to produce and generally have a higher return on investment.”

TITLE: Didact Twelve

GENRE: Sci-fi

LOGLINE: As he fights to preserve the legacy of the human race, a peacekeeper on a generational starship experiences a devastating personal crisis.

WHY YOU SHOULD READ: Writer didn’t provide one, but his email claims he holds a PhD. That’s gotta mean something, right?!

Amateur Friday Submission Process (read – slightly new!): To submit your script for an Amateur Review, send in a PDF of your script, along with the title, genre, logline, and finally, something interesting about yourself and/or your script that you’d like us to post along with the script if it gets reviewed. Use my submission address please: Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Remember that your script will be posted. If you’re nervous about the effects of a bad review, feel free to use an alias name and/or title. It’s a good idea to resubmit every couple of weeks so your submission stays near the top.

Genre: Drama

Premise: When a man involved in a fatal hit-and-run accident learns the victim is his brother’s wife, he must decide whether coming clean and appeasing his conscience is worth the risk of shattering his family.

About: Since the last time Recovery was up for AF consideration, back in November 2012, it’s undergone a page-one rewrite. The resulting draft garnered a quarterfinal placement in this year’s still active Page Awards, and I feel it’s ready for another shot at AF glory.

Writer: Harj Bains

Details: 90 pages

I don’t know why, but I see Joel Edgerton in this for some reason.

I don’t know why, but I see Joel Edgerton in this for some reason.

So what is a “page-one rewrite” (mentioned above in the About section) anyway? A page-one rewrite is when you scrap everything in your story and start anew. There are times where we write scripts that have inherent problems, and no matter how many times we rewrite them and rewrite them and rewrite them, it’s like adding a new shade of lipstick to a pig. It cleans’em up a little, makes them prettier. But the rewrites never seem to fix the underlying problem in the script.

Now most of the time when this happens, you eventually move on to the next script. At a certain point it just becomes so tiring trying to fix something you can’t figure out, that the best thing to do is to move on. But occasionally you have an idea that’s so good, or that you love so much, moving on isn’t an option. In these cases, where you refuse to give up, the best thing might be a page one rewrite. You see, one of the reasons it may be so hard to fix things is because you’re obsessed with some character or plotline or sequence that’s actually crippling your story. It made sense in that first draft. But as the script evolved and become something else, it doesn’t anymore. However, you’re so close to the material you can’t see what that troubling element is and therefore don’t know to eliminate it.

By starting over, by accepting that nothing in the previous script is necessary and you can take the idea anywhere you want again, you open up the potential of where the script can go NOW. Since today’s script is called “Recovery,” the proper analogy might be to see your script as a drug addict. And one day he wants to change. He wants to get off drugs. The problem is, all his friends are drug addicts too. It’s impossible for him to stop because he’s surrounded by drugs ALL THE TIME. It’s only when he eliminates those friends from his life that he can actually move forward and change.

Okay, enough with analogies. I’m not even sure Recovery is a true page-one rewrite. I just saw the author mention it and felt it was a good topic to bring up since we haven’t discussed it before. Now on to the script!

Recovery follows two 30-something brothers, Tommy and Daniel. Tommy is a functioning heroin addict. He’s got a job and everything, but he lives solely for his next high. Daniel is the brother who’s got his shit together. He’s got a nice job and a nice wife, Anna, who he loves with all his heart.

Well one morning, Anna wakes Daniel up because the treadmill isn’t working. He promised to fix it yesterday and she wants to get a run in before work. She asks him to please fix it but he’s too tired. He tells her to take a jog and he’ll fix it later today. He promises. She’s pissed but heads out for a jog.

In the meantime, Tommy, who’s exhausted coming off the high of one of his many shoot-ups, is forced to drive across town dead tired to sign a stupid form for work. On the way back, he’s falling asleep at the wheel, and wouldn’t you know it, there’s Anna running, and there’s Tommy not seeing her and BAM, he gruesomely slams into her.

Tommy’s awake now. At this point, he doesn’t know it’s Anna (we don’t know Tommy and Daniel are brothers yet, either). So he shoots off, freaking out and wondering how the hell he’s going to get his car fixed without someone reporting it. It’s a small town. If he’s not careful, the wrong people are going to know that the front of his car has a person-indent in the front, and then it’s only a matter of time before he goes to jail.

Not long after, Tommy is called over by his and Daniel’s parents. They’re all mourning the loss of Anna by a hit-and-run driver. Of course, they don’t know that their own blood, Tommy, was the hitter-and-runner. And it doesn’t help that Daniel is beating himself up over it. If he just would’ve taken the time to fix that damn treadmill, none of this would’ve happened. His wife would still be alive. Not to mention the fact that exercise is supposed to extend your life. What a lie that was.

After an elongated game of Tommy feeling awful as everyone around him curses this “anonymous” hit and run driver, Tommy decides to come clean. He tells Daniel that he did it. Daniel’s outraged at first, but realizes it was an accident. The event actually becomes the impetus for Tommy getting clean. He goes to rehab, even meets a girl he falls in love with, and a few months later he’s drug-free and ready to start a new life with this woman.

Uhhh, Daniel is NOT cool with that. His brother kills his wife, then gets a wife of his own out of it!!?? No, that’s not cool at all. Daniel’s rage takes him to the darkest of dark places, and we get the feeling he’s going to take care of this problem his own way. All of this is happening while detectives get closer and closer to finding out who hit Anna. But will they find out before Daniel decides to get revenge for his wife’s death?

I can see why you guys wanted me to read Recovery. Its first ten pages are kind of awesome, culminating in a brutal and memorable hit-and-run. But the rest of the script is kind of hit-or-miss. It’s actually quite the unorthodox story. It starts off as this thriller of Tommy trying to hide this dark secret, which is the section that had the most potential.

But then he actually tells his brother he did it. And when that happened, the story lost something. I mean, it was a brave choice. It was totally unexpected. And I love when writers take stories in an unexpected direction. But every choice must be the best choice for the story dramatically. It’s good to surprise the audience, but not if that surprise results in a loss of tension or conflict, which is what this choice did (in my opinion).

Harj tries to keep that tension up by cutting back to the detectives, who are trying to find the person who hit Anna. But there was something that didn’t quite work with that. We’re constantly reminded that if Tommy gets caught, he’s only going to jail for a year. In other words, the stakes aren’t very high.

The script ramps up a little towards the end when Daniel becomes enraged after finding out that Tommy’s getting married. We know that’s going to come to an explosive head. But that still left this big chunk in the middle of the script where the tension is non-existent.

Speaking of that middle, part of the problem is that Tommy’s girlfriend never felt real. Even now, 12 hours after reading the script, I can’t remember her name. She’s barely in a few scenes, and when it became clear to me what was going to happen (Tommy was going to fall for her and Daniel was going to get mad), I was disappointed. The girlfriend was a tool, a plot point. She was there to get Daniel mad. But she was never a REAL PERSON.

I see writers do this a lot. They need to create a plot element to advance the story, but they don’t make that element real. For this to work, we have to see Tommy FALL IN LOVE with this girl. We need long scenes showing these two losing themselves to one another. We need to give her her own hopes and dreams and problems and backstory so she feels like an actual person. Not just a plot point. Because the ending is based on this idea that (spoiler) Daniel’s going to kill Tommy for the love that he has and we don’t believe in this love. This moment needs to be TRAGIC. We have to die at the idea of this love being destroyed. But since we never get to know the girl, we don’t really care.

I think Recovery is an interesting script but it needs a little more meat. It’s only 90 pages long and it’s a drama. I always push for shorter scripts but dramas are typically the longest scripts out there because the genre DOES allow you to get into your characters more. And that requires more space and time. So this script should be at least 110 pages and those 20 extra pages should probably be dedicated to building the relationship between Tommy and his girlfriend into something more real. And making HER more real! I don’t think that’s going to fix everything. But it’s definitely going to give the script more weight. I wish Harj luck with it. ☺

Script link: Recovery

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Don’t just lay down an empty plot element. Every element in your story must feel real and authentic. If it doesn’t, we’ll see through the façade and know it’s only there for some plot reason. So with Tommy’s girlfriend, since she was never really explored as a character, we became keen to the fact that she was going to be used for something. And she was – Daniel’s motivation for revenge.

Carson here. Okay, a little background. I have this friend who recently broke into that oh-so exclusive “Hollywood Screenwriting Club.” In other words, people actually started paying him for his work. It was exciting to watch him finally get that recognition, go to meetings, officially tell people that he had representation. But as the months rolled by, I saw that he’d gotten a little down. So I asked, “Yo, Good Friend. What’s wrong?” And he assured me that while there wasn’t a day he didn’t wake up pinching himself for the opportunity to write for a living, he was a little crushed by some of the realities that go into the profession. As he started explaining them, I said, “You know what? Why don’t you write this all out and I’ll post it on the site? It’ll be like, a way for you to exorcise your demons.” He agreed that’d be a wonderful idea. So why am I posting this? To remind everyone that getting to the “spec sale” finish line is really just the start of a new race, a much longer and tougher race. Because now, instead of trying to be the king of the amateurs, you’re competing shoulder to shoulder with the heavyweights, writers who can all tell a good story (something you didn’t have to worry about in the amateur camp). You gotta work your way up. You gotta take jobs you may not necessarily like to pay the bills. It’s not easy. This is what he wrote…

Necessary dance for when you sell your first script.

Necessary dance for when you sell your first script.

When you sell your first script, you will cry.

I know that seems dramatic. It might be. But you’ve worked for this moment. Whether it’s for two years or twenty, writing is hard work—it’s impossible work. Squeezing your brain till it’s dry like brittle, staring at a glowing screen for hours until your eyes sting red, forgetting what it’s like to shower (or interact with other human beings). Writing is hard. Which is exactly what makes opening that email from your agent or manager and reading the words, ‘We got an offer’ so much sweeter.

So when you sell your first script, you will cry.

Because it feels amazing. This thing that you’ve been slaving over—outlining, emailing to trusted friends, fixing the outline, sending out again, fixing it one more time, scene-writing, banging your head against the keyboard, character work, act one is done (hurray!) oh wait it’s shit (boo!), rewriting, sending out, head-banging, writing, writing, writing, napping, read a professional script that makes yours look like a Hallmark Channel D-movie, writing, writing, almost there, final scene, DONE, sending out, rewrite rewrite rewrite, ignore these notes, apply those notes, rewrite rewrite, send to manager or agent and wait a million years until—someone actually LIKES it.

Liked it enough to, um, pay you for it.

And not just pay you. They want to make it. Into a movie. That people will watch. You IMDb the interested party immediately. Good resume, a few films under their belt, a couple you’ve heard of but have never seen. Netflix them—not too shabby, your script is better so you’re not worried because the movie’s getting made. The dream is here. In a year’s time you’ll be on a red carpet, smiling awkwardly for the cameras, right? Friends come out of the woodwork to ask about free screening passes, can you read their work, who is your manager—the uphill battle is over. You’ve made it, you’ve sold a script. Your bank account will go from $1.17 (checking AND savings combined) to some number that allows you to shop for actual groceries instead of driving thru Taco Bell for the 9th time this week. You’re gonna be sitting pretty in a dark theater with strangers laughing (or screaming, or crying, or ooh-ing and ahh-ing) at words YOU WROTE, watching actors saying things YOU MADE UP. Life. Is. Grand.

Except that doesn’t really happen.

Or maybe it does. Maybe for some people that’s really how it goes. But as far as I know, that’s like Supermoon Rare, an anomaly akin to Ahab’s white whale. That doesn’t mean selling your script isn’t awesome—it is, it’s just not the perfect, smooth sailing, seven-figure life changing event people make it out to be. But here’s what it does change:

It makes you hirable. Or, more hirable than you used to be. So you’ll get meetings. Sometimes generals, where people with a lot of power offer you a free water bottle (always take the free water bottle) and ask questions about the script you sold that they may or may not have skimmed over last week. Sometimes generals with baby producers who talk a big talk and name-drop every other sentence and try to get their talons into you early before a studio notices you. Let me just get this out now: BEWARE OF BABY PRODUCERS.

What’s a baby producer? That rando with one short film IMDb credit who blows up your inbox with questions about the script you sold, where’d it find a home, what are you working on now—that’s a baby producer. And they’re slick because the high of selling your script is just that—a very cool, ego-inflating high, and people will not hesitate to exploit it. You’ll think, Great! People want to hire me and read more of my stuff and having two produced scripts is CLEARLY better than selling one so why not?! I’m gone ride this wave of attention to the Academy and never eat Taco Bell again!! It’s easy to think this. It’s easy to assume that these people just want to make a good film and they read your work and loved it and trust your voice. It’s so, so easy.

It’s also incredibly stupid.

Baby producers are the worst. They’re dangerous. Because they’re inexperienced and because they’re inexperienced they’ve had to learn how to talk to get into rooms they have no business being in. So they’ll talk to you. But you’ll be naïve (well, you won’t because you read this article but anyways). So you’ll work. On insane timetables, too, because you’re riding that momentum from your script sale and don’t plan on losing steam anytime soon. You’ll work on their terms, with their ideas, and always with the understanding that you should be grateful for this opportunity to be writing for pay. You will write the first draft in less than a week. And the pay will be shit.

Meanwhile, you’re in rewriting hell from your own spec. There’s that saying, “Writing is rewriting.” That’s never truer than when you sell your script—because the studio or producer or independent prodco owns you. And they want a quality product. Oh, they liked your script, your ideas. But they like theirs better. So you’ll rewrite your precious baby into Kingdom Come to get their stamp of approval. After all, they are the gatekeepers here—they don’t like what you do, you get paid out and a shared credit with whomever they bring in. Which, as a new writer with an original spec, is not good news.

And you’ll learn that the feature world is harsh. That the writer is not the revered king but the lowly fool. That staying afloat in this pool requires some serious stamina—this is a marathon, not a sprint (and how many metaphors was that? yeesh!). You’ll learn that the producers are really the writers and most of the time they really aren’t writers but just think they are and they’ll tell you what darlings to kill. You’ll kill your darlings. You’ll do it reluctantly but you’ll do it.

You will question your own sanity. Notes will start to look circular—isn’t that how I had it in the original draft? why are we circling back??—and this script that you’ve lived with for months, years, will begin to haunt you. And you will despise it. It’s important, though, to realize exactly why this happens, why you might hate your own work so much at this point in the process: This is your baby. It’s been your baby since its conception. You know it inside and out, forwards and backwards and upside down. You saw it take its first steps, lose its first tooth. Then you sell it and someone else joins the family. Except they haven’t been living with the script for months or years—it’s new to them. This is both a blessing and a curse. Their perspective is fresher than your own, but it’s also not your own. Some ideas these new eyes have will be great, like Why didn’t I think of that?! ideas. Others will be awful, like, There’s a reason I didn’t think of that. Whatever the case, you’ll spend hours slogging through producer notes and draft after draft after draft until your eyes bleed from reading notes that tear your precious script apart piece by piece, slugline by slugline. And maybe, if you’re lucky, if you’re working with a producer who maybe kinda sorta knows that they’re doing, it won’t be so bad.

Maybe it’ll be good. Great, even. Awesome.

Because you sold your first script—the key word being “first.” I cannot stress this enough: This is a snapshot, not the whole picture. The trailer, not the movie. Somewhere along the way, this becomes clearer. You might complain about how hard the work is, how harsh and pointless the notes seem, how ridiculous and unprofessional the baby producers are, but you’ll realize that many people have this dream, and for you it’s now a reality. So you will shut up with the negativity and start to tell people when all that gratitude and excitement finally sinks in. And their reactions will be priceless. You’ll spend a lot of time answering questions from friends and family about when your movie is coming out (this will never stop until, I’m guessing, your movie actually comes out). And then you’ll smile—because that’s actually a very likely outcome to all of this. Your movie will come out.

Unless it doesn’t. In which case, it’s time to sell your second script.