Nothing gets movie lovers more juiced up than when you tell them one of their favorite movies stinks. So you probably don’t want to read this article if you’re still wound up from the holidays.

Barring the occasional exception, I’m not into bashing material. I like to celebrate movies, not call them names. Or at the very least, celebrate what we can learn from them, regardless of whether the screenplay/movie is any good or not. However, there are some situations where the claws come out. I hate when productions clearly don’t put any effort into the screenplay. It drives me mad. They think they can cover up a bad story with cool effects or a hot actor, even though that’s proven to never work. And then there’s that passionate movie-lover side of me that just gets pissed off when I’m watching a piece of junk. It’s no one’s at fault. But I paid for the thing so if I have a strong opinion on it, I wanna to share it with someone (or someones). Believe me, I know how hard it is to make a movie. I’ve tried to do it myself. Just getting a production in the can and then releasing it in movie theaters? That’s something 99.999999999% of the people on this planet could never do. So there’s a certain respect I have for anybody who can achieve that. But I’m still a film lover at heart, so when I feel passionate about something, good or bad, I want to get it out. So are you ready? Here are the ten worst movies I saw this year…

10) Brave – This is an interesting one because I wouldn’t use the word “hate” to describe my reaction to it. It was more like, “Huh?” We’re so conditioned to expect greatness from Pixar, particularly on the screenwriting side, that it’s baffling something like this could get through their system. They rewrite their scripts over and over again after numerous pre-viz previews and feedback sessions from some of the smartest story guys in the business. So why was this story so lame? And odd? And uneven? It just never seemed to know where it was going. I’ll tell you when I knew it was doomed – when the main character visited the witch in her little hut. That scene felt desperate as opposed to focused, like a production that knew it couldn’t dig itself out of the hole it’d dug and had to do a lot of dancing and ranting to distract you from the reality. Which was that this movie stunk. I still don’t really know what Brave was about. Talk about disappointing.

9) Paranormal Activity 4 – Look, let’s not forget what’s going on here. Paranormal Activity 4 is a cash-grab of the highest order. We shouldn’t be expecting much. Add onto that the tired “Paranormal Activity” format and this script had an uphill battle from the get-go. But seriously, ya gotta give us SOMETHING to latch onto. ANYTHING. This is the first scary movie I’ve ever seen…WHERE NOTHING SCARY HAPPENS! Even the promotional scare was lame (a girl rising above her bed). My friend and I looked at each other after this was over and said, “That’s it?” Then we looked down at a couple below us and they turned to each other and said, “That’s it?” I’d rather watch a 24 hour marathon of Honey Boo-boo than this again. What a boring movie.

8) Get The Gringo – Here’s the thing. Crazy Mel Gibson has been blacklisted from Hollywood. It means all his movies go straight to video now. But Mel’s still an interesting storyteller. He likes to try different things and has a pretty good eye for material. So I’m still willing to check out the stuff he does. That is until I saw “Get The Gringo.” This movie…was just…awful. As best I can explain it, Mel Gibson ends up in a Mexican prison, but this prison is actually a little town (yes, a Town Prison! WTF???). He then roams around this town speaking in long drawn out voice-overs that give us redundant insight into what he thinks about this new life of his. At some point, of course, a kid shows up and I think Mel becomes a surrogate father to him or something. But by then I was so bored I wanted to melt my eyeballs in the Mexican sun so I would never have to watch the second half of this dreadful movie.

7) Expendables 2 – I’ll probably take some flak for this one because the movie is supposed to be fun and stupid and silly and shouldn’t be taken seriously. But I just found the whole thing to be tired and obvious. Oh, they’re battling an army and then that army is mysteriously taken down by someone and then who should come out of the shadows but…Chuck Norris! I don’t know. I just felt like I was always ten minutes ahead of the jokes here. Nothing was surprising. The ONLY credit I give the movie is when I found out Jean-Claude Van Damme’s character was named “Villain,” yet pronounced in a French accent (so “Vil-ann”). Except I only got that joke by stumbling on the name when I was checking Expendables 2’s IMDB page. So the only good joke is one I didn’t get from the movie itself! And then there was the cinematography. Did they shoot this movie on a Best Buy camcorder? I mean seriously. This was the cheapest looking production I have seen for a Hollywood action film since the 80s. And then every scene felt like it was done in one take. There were awkward pauses, almost-botched lines – an overall feeling that actors had flown in for their 2 days of shooting and didn’t have time for second takes. I admit this is not my thing but this movie was stupid.

6) Battleship – This was bad. Wanna know how bad? It actually proved that you can try to make a movie like Transformers and do worse. I have a newfound respect for Michael Bay. I don’t know where to start with this one. You base a movie on the game Battleship, yet you turn it into an alien invasion movie? When were there ever aliens in the Battleship game? Then you populate your film with models and pop stars instead of actual actors? If we don’t believe the words coming out of the characters’ mouths, how can we believe what’s happening to them? Then there’s just the fact that the movie blatantly rips off Transformers, right down to the sound effects, which literally feel copy and pasted. I remember being halfway through this one, seeing a bunch of still ships sitting in the water, and thinking to myself, “This is quite possibly the most boring scenario you could’ve constructed for this movie.” On the plus side, the awfulness of this film should protect us from future board-game-turned-movie-properties like “Operation” and “Hungry Hungry Hippo.”

5) Rock Of Ages – You know how sometimes you can tell right away that a movie is going to be bad? There’s just something about the tone or the production or the directing or the acting (or all of the above) that isn’t synching right? That’s exactly how I felt watching Rock Of Ages, which follows a young girl on her way to Hollywood in a bus (which she sings about with her other passengers) then stumbles around a famous club when she finally gets there, then bumps into the famous owner and asks him for a job. It just felt…wrong. I have a lot of sympathy for musical productions because if you don’t nail the tone, they’re disasters that go far beyond typical movie disasters. And you could tell the director (who was it again?) wasn’t connecting with this material. It was overly cheesy, in-your-face and proud of itself before it had any reason to be. By minute ten I was actually starting to get angry. Like I wanted to beat the shit out of the characters. It was that bad. I may not have loved Les Miserables. But that movie knew what it wanted to be and it achieved what it set out to do. Rock of Ages misfired on every shot it took.

4) Total Recall – All I can say about this movie is that it was DOA. There was clearly nobody involved in this production who wanted to make this film. The writer didn’t seem interested in writing a good script (this script had the most boring intro you can imagine). The director didn’t seem interested in doing anything different (the evil soldiers were basically storm troopers – the set was a wannabe Blade Runner set). But worst of all, the actors didn’t want to be there. Colin Farrel was working at about 60%. Kate Beckinsdale was sleeping through her role. I dare you to watch the first ten minutes of this movie and be interested. It’s impossible. This movie is dead. It really is. It’s like watching something that has died on the side of the road.

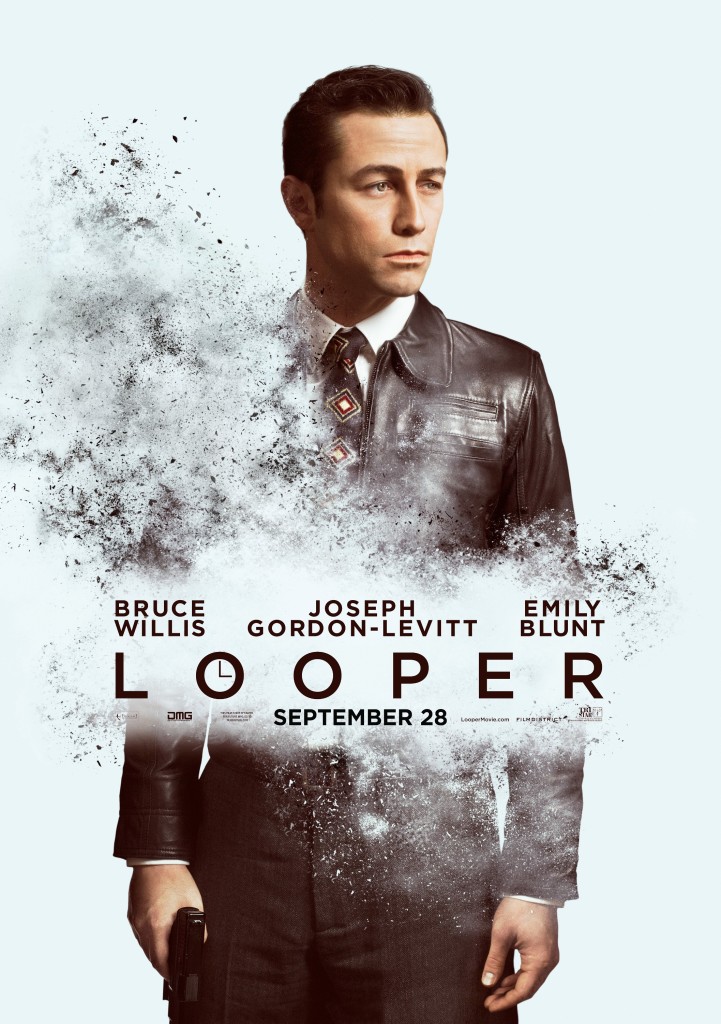

3) Looper – Okay okay. So maybe I was a little rough on this one in my review. I didn’t list a single good thing about it when there were a couple. The scene where the guy is slowly losing his body as he’s trying to run away was great. And really, the whole first act was solid. But after that, this movie completely falls apart, and it really is one of the most poorly told stories of the year. The China stuff was weird. Everything that happens at the farm house is boring. And the telekinesis plotline was forced in by the writer solely so he could shoot those gravity effects. There was nothing natural about its inclusion at all, which is what revved me up so much. What’s strange is I get all these hush-hush e-mails from people saying, “I went to see Looper, Carson. And you were right. I can’t believe how much love this film is getting. It’s terrible.” As if we’re living in 1936 Germany and the mention of Looper as a bad movie will get you executed or something. Rian Johnson is a well-loved geek-centric director so I understand it’s not trendy to dislike his movies. I get that. But you gotta call a spade a spade. This is 1/3 of a good movie. The rest is a mess.

2) Dark Shadows – I was actually excited to see this one when it came out on video. The previews made it look funny. Johnny Depp as a fish-out-of-water ancient vampire unleashed upon a modern world? That’s comedy gold right there. But Holy sh*t! NOTHING HAPPENS IN THIS MOVIE. And I mean NOTHING. Johnny Depp wakes up, shows up at the house, then hangs out and does nothing for the next 90 minutes. There was no point to this story, no urgency, nothing for the characters to do. You know how you’ll be watching a movie and at a certain point you’ll sit up and declare out loud, whether there’s anyone around or not: “What the hell is this about????” That’s what happened to me. Thank God for Twitter, which allowed me to get some of my frustrations out on this one. One of the few movies of the year where I considered asking for my money back.

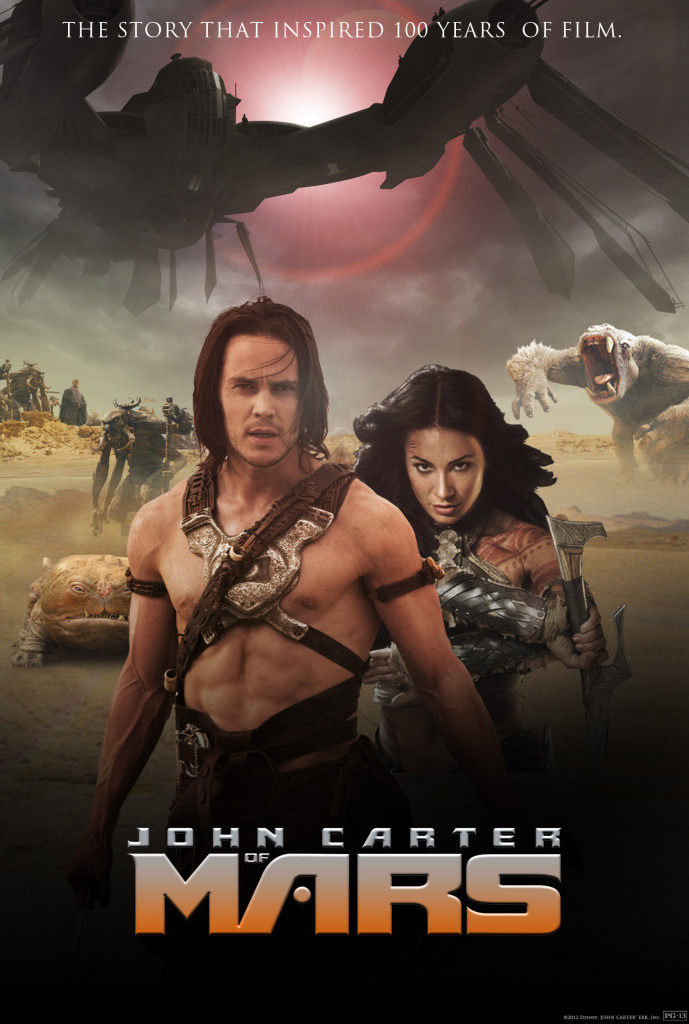

Tie-1) John Carter of Mars – I thought Cowboys Vs. Aliens was the most misguided concept of the last five years. Well move over CvsA. John Carter’s taking the poll position. Here’s what I don’t understand. This character was created in 1912, when, like, it wasn’t unheard of to think that aliens lived on Mars. But we live in 2012, when we definitively know there are no aliens on Mars. It’s just a big dry dusty rock. So how do you convince audiences that that’s not the case? I just don’t see anybody making that leap other than 6 year olds and people who loved the old novels. So it was such a misguided concept to begin with. But when John Carter started jumping? Like we established his power as “super-jumps,” I’m not going to lie, I started laughing. I mean how can I take a movie like that seriously? And then it just got worse from there. The designs of the ships didn’t seem to have any connection to the world itself. The mythology was bizarre and hard to wrap your head around. I didn’t like any of the characters. The aliens were most boring and annoying. This was an easy pick for biggest misfire of 2012. But it’s not the only pick!

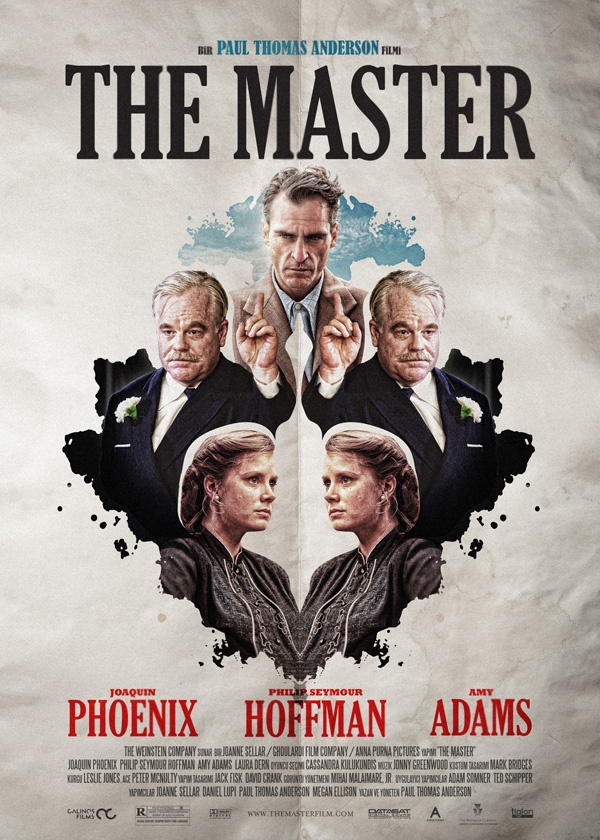

Tie-1) The Master – This movie was just freaking awful. It’s as if PTA was drunk when he wrote it and high when he shot it. You can tell me a PTA screenplay can’t be judged by conventional screenwriting methods until you’re blue in the face. It doesn’t give the writer license to make a boring wandering piece of crap. I mean at least “There Will Be Blood” had a design to it. You could feel it building. This was just a mess. It was a student film with a 20 million dollar budget. One of those Saturday afternoon deals with your classmates where you try a whole bunch of shit on camera and figure out how you’re going to edit it together later. You’ll never be able to convince me that PTA had a plan in place here. He was making this one up as he went along, and you could feel it in every minute of the movie. The only thing saving this one from a universal drubbing are the performances. But even those, while interesting, are inconsistent, especially Phoenix’s. If this would’ve been shown at midnight at some offbeat film festival and it was labeled as “experimental,” I wouldn’t have been so hard on it. But if you’re going to package this as a real movie, that’s how I’m going to judge it. And on that level, this was a monumental failure.

Whoa! I got a little revved up there, didn’t I! I fully expect retaliation for the “Master” and “Looper” choices, but after you’re done yelling at me , let me know what your least favorite movies of the year were. And for those who can’t stand movie-bashing, I’ll be listing my favorite movies of the year either Thursday or Friday. So re-join me then!

Black List? Hah. Hit List. Nope. My top 10 screenplays of the year!

For those of you disappointed that the end of the world didn’t come, I say to you, chin up! A new year is upon us, which means new possibilities, new frontiers, new chances to sell your script. For a little inspiration, let’s look back at the best scripts of the year. Or, at least, the best scripts of the year in my opinion. Which is, of course, the only opinion that matters. For those of you unfamiliar with my end of the year “Best Scripts” list, they don’t always fall in line with my Top 25. I know that makes zero sense, but some scripts burrow into your soul and stay with you all year while others burn brightly at first but fade faster. Still, you’re going to see a lot of familiar faces here, and a couple of surprises. The scripts on this year’s list have a few things in common. They’re either shocking, consistently surprising, really well-written, have a unique voice, have amazing characters, or all of the above. Wanna take a look? So do I!

10. Promised Land – Promised Land is about as “plain” a script as you can get away with and still have it be great. We’ve got a small town. We’ve got small characters. For a script like this to work, the writing has to be top-notch, and it is. I think what stayed with me the most was how much pressure was put on the main character. That pressure created high stakes, which made us care about whether our hero was going to succeed or not. This is something I felt a script like Lincoln really failed at. Despite the 13th Amendment being one of the most important moments in history, the writer managed to make Lincoln’s plight feel only a fraction as important as Promised Land (yes, I just used Promised Land to take one more shot at Lincoln). Anybody seen this movie yet? How is it?

9. Untitled Arizona Project – Rarely does a script with just one great scene leave such an impression on me, but this one did. Yes, I’m talking about the Squirrel Scene. For those unaware of the Squirrel Scene, just imagine being trapped in a confined space and then being bombarded with hundreds of terrified angry squirrels. Yes, that actually happens in this script. But this is also one of the unique voices I was talking about. You’re so unsure of what these bizarre one-of-a-kind characters are going to do next, you can’t help but continue reading. I remember reading this one like it was yesterday, which I can only say for a handful of scripts.

8. Echo Station – Is Echo Station benefitting from the freshness of only being read a week ago? Probably. But I always admire a time-jumping or time-looping narrative that stands up to plot scrutiny. Usually these scripts fall apart faster than a flan baked by your Cousin Edna. Can it handle scrutiny by the super time-travel script assassinators? Probably not. But I’m not sure any time-travel movie can. I mean, those guys could find fault in Back To The Future. I also think Echo Station is a great reminder of what kind of spec gets noticed in the industry. A little hook, a lot of urgency, and some high stakes.

7. The Disciple Program – The Disciple Program is a little like Star Wars at this point. I’m not sure I can say anything new about it. So I’ll just remind you of how the script was written, which continues to fascinate me. TDP was written 10 pages at a time for a contest. Each of those 10 pages was vetted by a judge and those notes sent back to Tyler. So every time Tyler had to turn something in, those self-contained 10 pages had to be exciting and memorable in some way. This is why the script stays consistently good, because you know every ten pages something interesting is going to happen. Now is this a surefire way to success? No. I’ve read some of the other scripts that were in the competition and they didn’t light the world on fire. But it’s still a solid technique that every screenwriter should try at least once.

6. Origin Of A Species – For those who don’t remember, this is the script that won Amazon’s Screenwriting Contest. I’m still kind of surprised by how much flak that contest got. They gave out gobs of money to screenwriters, more than any other competition by far, allowing many of those writers to obtain some momentary financial freedom so they could continue their dream, and they did it over and over and over again. And they also found this script, which was a really original voice and a story so far removed from conventional structure that I needed Google Maps to get me back on track. This writer has a hell of a talent for making small moments interesting. He’s also great with dark moody material. I haven’t stopped thinking about this one.

5. Saving Mr. Banks – To me, the scripts that really give me hope are the ones that I have no business liking, and yet somehow they win me over. I’ll tell you why: Because it reminds me that the most important aspect of your screenplay is your characters. Characters can exist in any world, whether it be space, football, lumberjacking, or children’s book authoring. If they’re interesting enough, if they’re relatable and compelling enough, we’ll wanna see what happens next. There was no reason I should’ve loved a script about a bitchy middle-aged woman complaining about her children’s book being made into a movie. It’s a testament to the writing that I did.

4. The Ends Of The Earth – Myself and the word “sweeping” don’t generally hang out at the same coffee houses. “Sweeping” is something I’d expect from a romance novel. Which is ironic, I guess, since “Ends Of The Earth” is a love story. Although it’s nothing like the love stories you grew up on. This ain’t no Nicholas Sparks, that’s for sure. I won’t spoil the big hook since, if you ever read the script, it’s best to go in knowing nothing. I’ll just say that, despite its defiance of my coveted GSU, it again goes to show that if you have two compelling characters at the heart of your story, you can get away with a lot of structural defiance.

3. The Equalizer (no review) – Here’s the thing. Every star is looking for a franchise. Everyone wants their Bourne, their Mission Impossible, their Die Hard. Because successful franchises mean longevity. If your career ever goes south (and it can happen folks – remember when Val Kilmer was an A-list actor?), you can pull out another episode from your franchise and you’re back in the mix. It’s why Cruise grabbed onto the Jack Reacher books. It’s why Wahlberg attached himself to Disciple. But franchises can’t become franchises unless that first movie kicks ass. And man is this movie going to kick ass. People have complained about the fact that Denzel’s character never once seems to be in danger. And usually that kind of thing bothers me. But there’s something about how this guy is built that you can’t wait to see him beat down the bad guys. He’s almost like a superhero. You know he’s going to win, you know they don’t have the skills to beat him, but you don’t care. — Equalizer also has the distinction of being the best SCRIPT I’ve read all year. What I mean by that is the writing is so crisp and clean and descriptive and to-the-point. It consistently conveys a ton of information in very few words, which is the essence of good screenwriting.

2. Django Unchained – Quentin is the master of scene-construction. Each of his scenes is like a mini-movie with a set-up, an implied collision, and a climax. I don’t know how anyone writes a 160 page screenplay and has me riveted on every single page. If not for that late scene (spoiler) where Django artificially cons his captors into letting him go – the only point in the script where I was aware of the author’s pen – this probably would’ve been my number 1. But other than that – awesome! I mean what a unique fucking story. A German recruits a black slave to become his apprentice in hunting down slave owners? Genius! And in classic Tarantino fashion, you’re never quite sure what’s going to happen next.

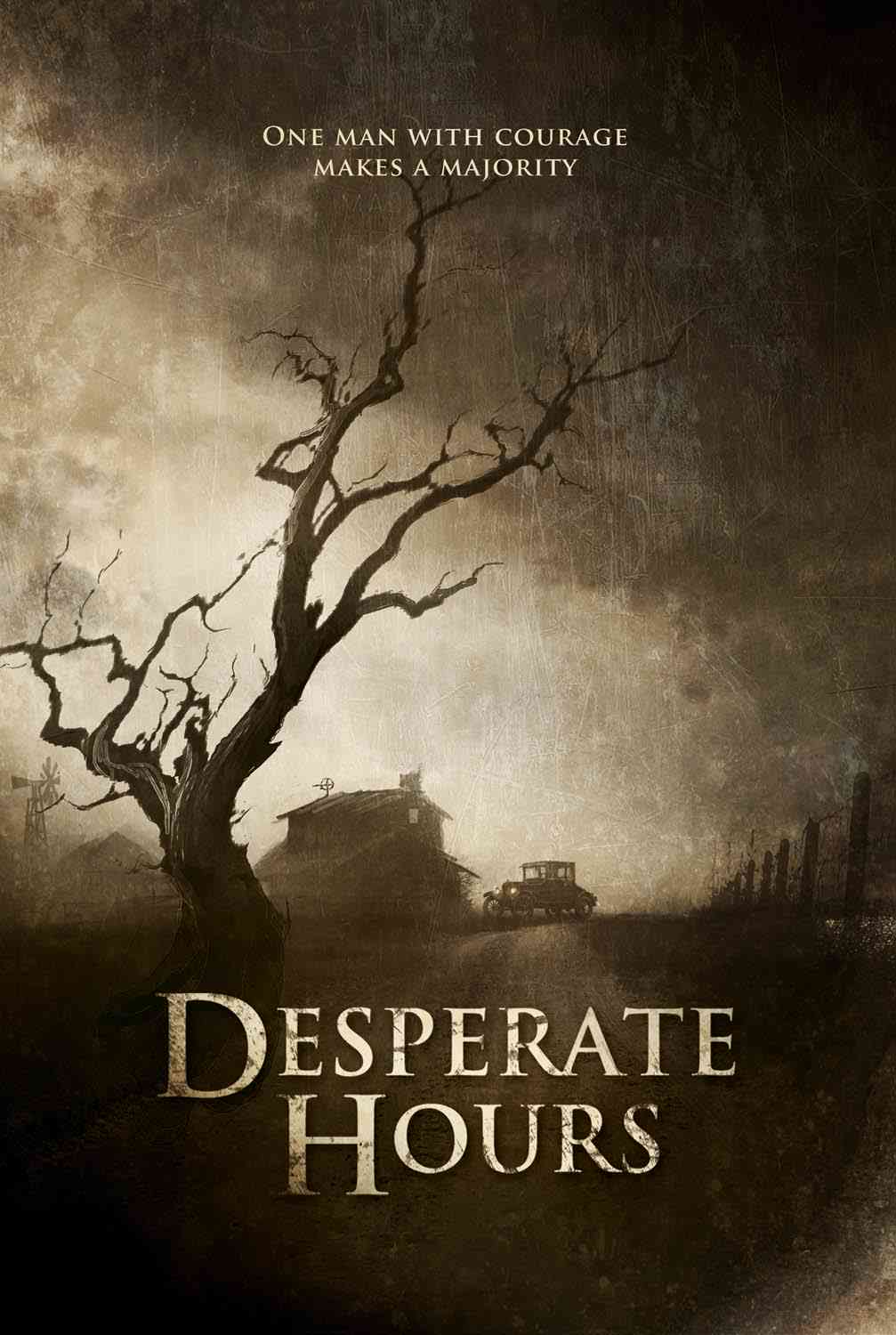

1. Desperate Hours – Third act. Third act. Third act. Leave them riveted as they close the final page and they’ll go racing to tell everyone they know about your script. The third act of Desperate Hours is absolutely un-freaking-believable. I don’t know if I’ve ever read a script where I’ve agreed with every single choice the writer made, but I did here. There is so much skill on display in “Desperate,” so much mastery of craft and structure, you’re going to need a scalpel to scrape it all out. The two big knocks on the script were a lack of memorable dialogue and a slow opening. For whatever reason, neither of these bothered me. I usually like realistic dialogue as opposed to the fancy memorable stuff, which is probably why the absence of flash didn’t occur to me. And I was curious enough about the main character that the first act moved quickly (I was intrigued to learn how he had gotten to this point!). I just loved this script. It’s wrapped up in Johnny Depp Land at the moment. Here’s hoping Depp doesn’t wait another 15 years to make it, but rather offers the lead role to another actor.

That’s it for me folks. Doesn’t look like there’s going to be a post tomorrow due to it being New Year’s and all. I’m not a huge partier but even I have to have a little fun every once in awhile. This should give this post plenty of time, however, to get all of your Top Tens in. I’d love to hear about some scripts I haven’t read yet. HAPPY NEW YEAR! (note – I still haven’t transferred the comments over from the old site so sorry there are no comments on these older posts).

Say you could clone a younger hotter version of your wife? Would you? Better be prepared for the consequences.

Amateur Friday Submission Process: To submit your script for an Amateur Review, send in a PDF of your script, a PDF of the first ten pages, your title, genre, logline, and finally, why I should read your script. Use my submission address please: Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Your script and “first ten” will be posted. If you’re nervous about the effects of a bad review, feel free to use an alias name and/or title. It’s a good idea to resubmit every couple of weeks so your submission stays near the top.

Genre: Romantic comedy

Premise: After watching his marriage implode, a scientist creates a cloned version of his wife, yet gets in trouble when his ex-wife wants to get back together.

Writer: Brett Martin (story by Brett Martin and Ben Liska)

Details: 105 pages

“Clone Wife” is the kind of title you could see pinned on an 80 foot billboard standing above the 405 Freeway. It’s high concept, something that sells itself without having to know anything other than the premise. That’s when a high concept is really doing its job, when just its title or a quick sentence gets you thinking of a million different scene possibilities. And “Clone Wife” had me doing just that, which is a big reason why I chose it.

I also chose it because two independent sources e-mailed me to tell me it was a good script. And whenever you get an independent referral, it’s a good sign. It means someone’s already vetted the screenplay and, without anything in it for them, vouched for it. Of course, now that I think about it, I didn’t know the two people who wrote in and vouched for it. I suppose they could’ve been the writer in disguise. But after reading it, I can see how someone might recommend “Clone Wife.” It FEELS like a screenplay. It SMELLS like a screenplay. It TASTES like a screenplay. There’s something overtly professional about Clone Wife. And yet there’s something missing as well. Ironically, one might argue the script feels like a clone itself. It looks the way a script is supposed to look, but lacks the depth and detail of an original.

The story’s simple enough. 37 year-old Travis Wonders is an inventor/scientist. Instead of a man-cave, he has a lab-cave, complete with little robotic assistants that bear a striking resemblance to the one Iron Man uses. Travis is a hardcore workaholic, putting the bulk of his efforts into cloning, and it’s driven his wife, Renee, crazy, to the point where she’s decided to leave him.

This takes poor Travis by surprise, and the next thing he knows, Renee has left for Japan! Bummed out, Travis goes into a mumblecore-like tailspin, complete with Chinese food take-out containers strewn about and the ubiquitous 3 day old beard. But then one day he wakes up to see that Renee is in his bed. But not just any Renee. A REALLY HOT, YOUNG RENEE! Just like that, things are looking up!

After doing some digging, he realizes that his robotic apprentices cloned a 9-years-younger version of his wife, which would make her only one year removed from when they first met. Which is exactly how she perceives the situation. She believes their relationship has just started, and that it’s actually 9 years ago.

Travis decides to engage in the relationship because…well because the real Renee left him! But that’s about to change as Stig, Renee’s brother, convinces the real Renee to come back and give Travis another shot. Travis quickly finds himself in the precarious position of trying to get his real wife back while staving off the fake one. Or vice versa. Or verse vice-a. It all gets pretty tangly, and however it shakes out, it’s probably not going to be pretty.

Like I said, this FELT like a screenplay, but there were a lot of little problems (and some big problems) that, when added up, hurt the reading experience. Let’s start with the characters. I have a simple equation for a romantic comedy: We gotta like the guy. We gotta like the girl. We gotta want them to get together. If your romantic comedy doesn’t hit those three marks, there’s a good chance it won’t work.

I kind of hated Renee. She was bitchy. She was usually upset. She was a bit of a whiner. Even after she came back to try the marriage again, she immediately gets pissed off. There was never a time where she seemed nice or cool or fun or someone I might actually enjoy being around. Then there was Travis, who comes off as so oblivious and unaware that it was hard to sympathize with him. Renee is telling him she’s moving on and his reaction is, “But what about our dream, Moonbeam?” Why would you break out a cute rhyme when your wife just told you she’s leaving you forever? Yet that’s Travis. He never appears to exhibit any genuine emotion.

So I didn’t like Renee. I didn’t get Travis. Naturally, then, I didn’t care if they got together. And once you don’t care if the leads are getting together in a romantic comedy, what’s the point? It’s like when I accidentally turned into oncoming traffic at the beginning of my first driver’s test. Both myself and the instructor knew he was failing me, but he made me go through the rest of the test anyway. Why instructor? Why??

Then there was the introduction of Clone Renee. I still can’t figure out how she came to exist. From what I understand, Travis’ robots created her. So let me get this straight. Travis has spent HIS ENTIRE LIFE trying to clone something, with his biggest achievement being holding together organic matter for .2 seconds before it exploded. Then a couple of robots are able to clone a woman while he’s sleeping? I always try to get this across: Don’t fudge your major plot points. Major plot points need to make sense! We’ve set up that cloning is impossible. So how do robots do it??

I’m not sure I dug the on-the-nose nature of the script either. Our main character is named “Travis Wonder,” which seemed a little forced. Our villain, Guy, who used to date Renee when she was a prom queen, has since gone on to write a bestselling book called “Marry that Prom Queen.” He spends the plot trying to – you guessed it – marry the former Prom Queen. .

I also felt the humor was scattered and hard to get a handle on. For example, there’s this whole humorous subplot where Clone Renee is confused by all the modern technology (since she still believes it’s 9 years ago). I don’t think a script called “Clone Wife” should deal with characters who are wowed by the future. That’s a different comedy altogether. And then there’s a running “Scarface” joke, even though, for the life of me, I couldn’t figure out why anything in the story would be affiliated with that movie. Maybe if the story was set in Miami?

If I were Brett, I’d take a step back and remember what we’re after. Romantic comedies, at their core, are character pieces. They’re characters learning about themselves through each other. That means establishing flaws for each character and using the journey to show them overcoming those flaws.

I think Brett’s trying to establish that Travis is a workaholic, a good flaw for a romantic comedy. However, the key scene inside those first 15 pages is Travis driving Renee to their high school reunion only to be told by Renee that the High School Reunion is next month. Besides the weirdness of this scene (why would Renee wait until they got to the high school to tell Travis they’re doing something else?) the purpose of the scene seems to stress more that our main character is forgetful, not a workaholic. So right from the start I had the wrong impression of Travis

Assuming we clear that up, the next step should be Travis trying to reverse the mistake that lost him Renee in the first (being a workaholic). So now, when Clone Renee enters the scene, he should be caring for her, doing things with her, being there for her to a fault. Then Real Renee comes back into the picture to complicate things. That’s what bothered me about Clone Wife. There was no real exploration of the main character’s issues.

It’s so hard for me to say this stuff because Brett definitely put a lot of effort into this. But I think too much of the focus was put on WRITING the story and not TELLING a story. I would try writing this as a character piece and let the comedy emerge from that, as opposed to directly looking for ways to exploit the premise. Let your characters take you places instead of forcing the places upon them, as the story almost always goes to an artificial place in those circumstances. That’d be my advice. What’d you guys think of Clone Wife?

Script link: Clone Wife

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: With Clone Wife, I got the feeling that every little period was scrutinized over. Which can be a good thing. But sometimes it can kill a script in the same way that a speech can be over-rehearsed. If you try to make every little sentence too perfect, too cute, too measured, you lose the naturalism a script needs to read well. So really, after you get your script into perfect shape, consider going back and “dirtying it up” a bit. As counterintuitive as that sounds, some of us over-writers need to do it.

A spec screenplay with no Black List play makes a strong late-year debut and asks the screenwriting community, “How could you miss me?”

Genre: Sci-fi

Premise: A top secret deep space crew comes upon a strange deserted futuristic ship. After boarding, key members of the crew start experiencing time loops.

About: Echo Station was recently shot in Australia with Daybreakers directors Michael and Peter Spierig at the helm. Half of the writing team, Patrick Aison, recently sold Black List spec “Wunderkind” to JJ Abrams’ “Bad Robot.”

Writers: Patrick Aison & Brad Kean

Uhhh, how in the world did this not make the Black List??

Everyone but two people have told me it’s awesome. I was a little skeptical because people have called it “the next Source Code” and I’ve read several “next Source Codes” and they’ve all been full of programming glitches. But holy shit, Echo Station comes close! I thought the time loop device was dunzos after it reached Gangnam style use in the screenwriting community, but these guys figured out a way to make it fresh.

What shocked me most was how lost I got in “Echo.” I know I say that every time I read something good, but it still surprises me. In 95% of the scripts I open, I’m already thinking about the writing by page 2. I’m considering the writer’s choices or annoyed by how hard the prose is trying or upset by a weak character introduction. When somebody’s able to grab you and pull you into their story so you’re not thinking about any of those things – that’s a hell of an achievement. Even doubly so today due to the “This won’t be as good as Source Code” chip on my shoulder.

The plot here is really cool. It’s the near future and we’re in a space station far away from earth because they’re doing top secret dangerous experiments. The military has just sent up Air Force Colonel John Cole to take a look at the place and make sure everyone’s doing the jobs they’re supposed to do. The crew is wary of the corporate invasion and therefore don’t take kindly to Cole’s visit.

The key players on the 7 person crew besides Cole are Viktor “Stas” Stanislas and Natalie Rouvier. Stas is technically still married to Natalie but things clearly aren’t cooking at home anymore. And it doesn’t help that the strapping Cole immediately makes a connection with her. If you’re guessing that’s going to play into the story later, you’re guessing right.

“Later” doesn’t take long, as almost immediately after Cole docks, the crew is shocked to spot a sleek deserted futuristic ship called the “Amaranth” gliding past their station. Naturally curious, the seven of them jump in the shuttle and chase after the thing, docking soon after. After some initial analysis, it’s clear that the ship is decades ahead of any technology they’ve ever seen. Which is spooky in itself, but spookier in that there’s no one onboard.

A few hours after poking around, a surprise meteor storm hits the ship and the thing is ripped apart. But as everyone’s dying a horrifying fiery space-vacuumed death, a flash of light comes and Cole finds himself back in the compression chamber of the ship right before boarding. He’s looped back.

Naturally, he doesn’t know what the fuck just happened, but when he tries to tell the crew, they all think he’s nuts. Until, of course, the meteor shower hits again. And kills everyone again. And Cole loops back again. Cole quickly realizes that if he doesn’t figure something out, he’s going to be looped inside this ship forever. But that’s not the only thing he has to worry about.

After a dozen loops, Stas approaches him. Stas has been looping too. For a good three weeks. Which you’d think would be good news because now Cole has someone to brainstorm with. But Stas seems to look at this looping a little differently than Cole. He humiliates people, beats people up, tricks them, hurts them, all under the guise that they’re going to be looped back anyway so who cares? Stas has one simple rule for Cole. You can go do whatever you want, but stay away from Natalie.

But after awhile, Natalie becomes aware of the loops too, and her and Cole start scheming to figure out what Stas is up to. What they find is beyond disturbing. Stas has been looping for much longer than he’s let on. And video from those loops shows that he’s done everything imaginable to every member of this crew, including killing them hundreds of times. Stas has made Echo Station his own personal playground. If they don’t figure out a way to stop the looping and get out of this, they could be stuck in Stas’ hell forever.

I think the scripts I like best are the ones with an intriguing mystery at their core and a strong goal. Because, to me, those are two of the strongest story engines you can arm your script with. With these time-looping stories, it’s all about “Why is this happening?” That’s an intriguing mystery I want solved. My problem with this device, typically, is that the answer to that mystery is never satisfying. Here it was not only a great revelation, but it actually made sense!

(Spoiler) The reason the ship is looping is because it has a defense mechanism so that it can never be destroyed. If it encounters anything that disables it beyond repair, it jumps back in time to before it happened, theoretically allowing the crew to avoid the problem before it happens. That made total sense to me and I can’t tell you how important that is. Most writers will write In the cool mystery and figure that’s enough. “Oh, it doesn’t really matter WHY it’s happening,” they’ll convince themselves. “As long as it’s cool, who cares?” Err, no. When your script is more than a jumble of ideas, when it actually follows real-world logic and there are solid REASONS/MOTIVATIONS for things happening, everything about your story solidifies, because the reader TRUSTS you. They know you didn’t just throw this together on a Saturday night. This is a story with some real thought and effort put into it. And those are always the best scripts.

And the goal here is strong too, of course. Get out of the loop! That’s the thing with goals. The best ones are usually simple and obvious. It’s when we’re NOT sure what the goal is that we lose interest in the story.

If the script has a fault, it may be Stas. Don’t get me wrong. I thought he was a wonderful villain. But the more I thought about his motivation, the more I questioned it. He was okay with living this same loop over and over again so that he could be God, despite having to spend it inside a confined ship within a 4 hour time frame? I’m assuming you’d get bored with that after awhile.

Still, he was one fun little bastard. I both loved and was horrified by the videos showing Stas provoking crew members in early loops, then using subsequent loops to learn how they fought and anticipate their attacks in order to defeat them effortlessly later on. It really made the end a blast because you were genuinely terrified of this guy. You knew there was no way he could be defeated because he literally knew everything you’d do before you did it.

I would’ve liked to have known a little more about a few loose ends though. A cool revelation was when they find a picture of Stas, 20 years older, as one of the original crew members on the ship. This had my mind racing throughout as I tried to figure out what that meant, but I’m not sure it was ever explained. Also, how did this ship get here in the first place? It appears to be from the future. But that’s all that’s known. And yet, a part of me kinda liked it. It gave the script life after it was over, as it still has me wondering what it was all about. I guess that’s what happens when you read a great script. You even like its faults.

This is easily one of the best scripts of the year. I guess it just didn’t get the exposure it needed in order to make The Black List. Which reminds me, have you guys read anything good on the list yet? A few people have e-mailed me to say that “Devil’s At Play” is awesome.

[ ] Wait for the rewrite

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Take a popular device/story type/character type and EVOLVE it. If all you’re doing is giving us the same device we’ve seen in other scripts, you’re going to look like last guy on the block to own a Mini Cooper. Especially if you’re integrating a recent trend, like time-looping. Echo Station evolves time looping by having MULTIPLE CHARACTERS LOOP. This adds all sorts of character and plot possibilities we hadn’t seen before. People are hiding loops from each other. People are using their looping experience against one another. It just made the device feel fresh. You should always try and evolve the type of story you’re telling in some way so that it’s different from from came before it.

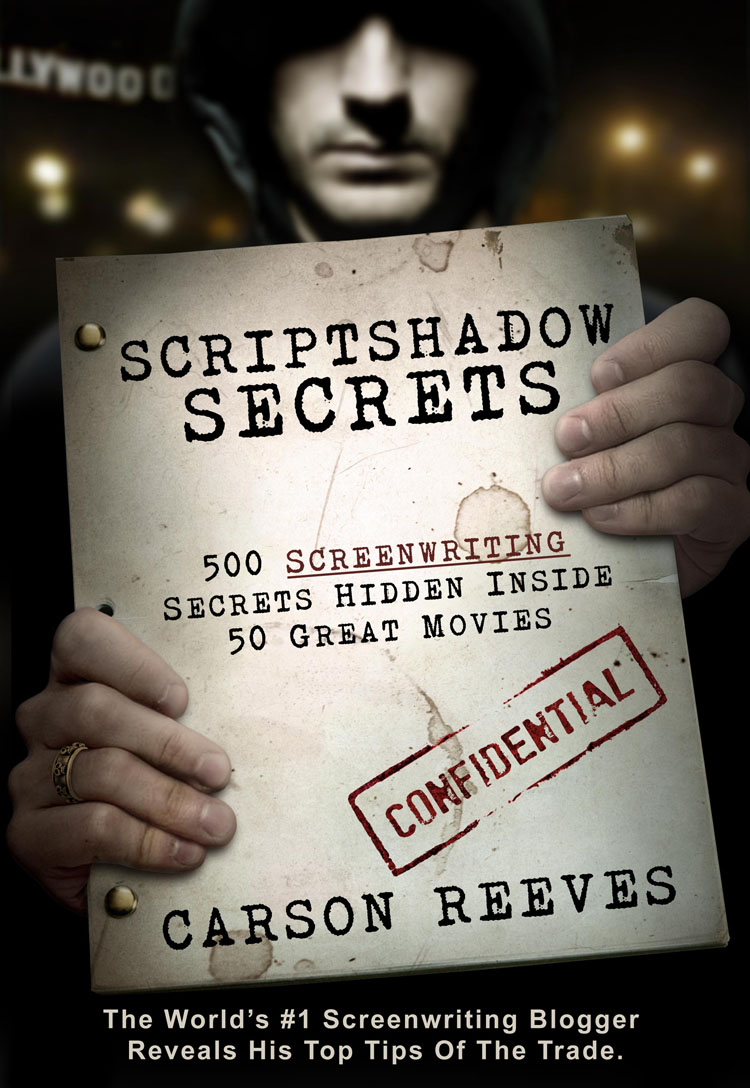

UPDATE: There are still countries where the discount hasn’t updated yet, so I’m going to keep the $4.99 special going on for one more day (Wednesday). Take advantage!

The book with more screenwriting tips than you’ll know what to do with is just $4.99 through Christmas Day. Snatch it while you can. And Merry Christmas! (non U.S. Amazon territories will see the discount show up within 24-48 hours).