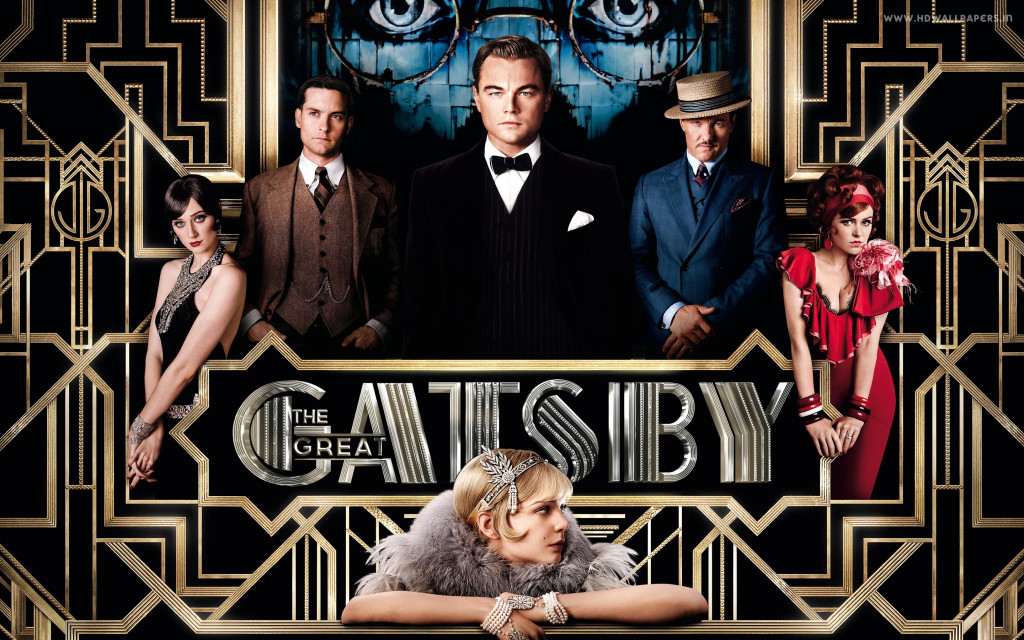

The Great Gatsby had the best use of 3-D I’ve ever seen. But how many dimensions did the actual storytelling have!?

Genre: Drama/Period

Premise: Set in the 20s, a former writer moves next to one of the wealthiest men in New York. When the man, a shadowy figure known as Jay Gatsby, invites him to one of his famous parties, he finds his life forever turned upside-down.

About: So if the frustration of coming up with a title for your script is beating you down, note that as far back as 1925, writers were still battling the issue. Believe it or not, F. Scott Fitzgerald was set on calling his novel “Trimalchio in West Egg.” It was only after friends convinced him that the title was non-specific and un-pronounceable that he turned to the title we know today. Something tells me had he not made that choice, none of us ever would’ve heard of the novel. Which makes me wonder: How many unknown classics are out there because of bad titles? Speaking of, here’s a little known fact: Gatsby was not a hit when it was first published. It was actually a bomb, leaving Fitzgerald to die believing he was a failure. It was only during World War 2 when schools started using Gatsby in their curriculum that it went on to obtain the status it has today. Baz Lurman and his longtime writing collaborator Craig Pearce adapted the novel for the screen.

Writer: Baz Luhrman and Craig Pearce (based on the novel written by F. Scott Fitzgerald)

Details: 2 hours and 20 minutes long

I love this shit!

A non-comic-book, non-franchise, non-sequel, non-YA-novel-adaptation, non-Johnny-Depp, non-Pixar CHARACTER PIECE comes out in the most competitive part of the year and cleans up 50 million at the box office. Now THAT is encouraging. It makes me believe in the purity of the screenplay again. True, it did have one of the biggest movie stars in the world and the script is an adaptation of a book. But The Great Gatsby is hardly what I’d call a surefire hit. It’s a character study from the 1920s!

Now believe it or not, I’ve read The Great Gatsby. I realized a few years back that there was an off chance I might run into a literary snob at a party who saw screenwriting as an inferior type of storytelling, and this literary jerk-off might corner me with the inquiry, “And what book have YOU read recently, Carson? Or do you even READ books?” In which case I could answer, “Oh, I actually recently read The Great Gatsby. I try to revisit a classic every month or so.” And then I’d triumphantly march off, leaving a bunch of startled partygoers in my wake, amazed at my unending literary know-how. This moment hasn’t happened yet. But it will. Oh trust me – it will.

Now for those of you who ignored your reading assignments in high school or don’t revisit the classics every month like I do, The Great Gatsby is about this guy named Nick Carraway, a writer turned bond trader who moves to Long Island. While Nick is a man of modest means, he seems to have tons of friends who are uproariously rich – like his cousin Daisy, Daisy’s bestie Jordan, and Daisy’s husband Tom (a polo star).

Coincidentally, Nick’s shack is located next to another rich man, Jay Gatsby. Though he holds the biggest parties in town, nobody seems to know who Gatsby is or what he looks like. Well, one day the mysterious Gatsby sends an invitation to Nick to join one of his parties, and despite senators and mayors and celebrities and sports stars attending, Gatsby only seems interested in speaking with Nick.

Fast-forward a bit and we find out that the reason Gatsby is so keen on gaining Nick’s friendship is his secret past with Nick’s cousin, Daisy. It appears the two fell in love many years ago when Gatsby was a poor nobody soldier. The two couldn’t be together because of his lack of wealth, though, so Gatsby went about amassing as much wealth as possible over the last half-decade (most of which came from underground bootlegging) and has come back bigger and richer than everyone in town, all in the hopes of snagging Daisy, a task that’s become tricky seeing as she’s now married. In the end, the lives of all of these rich (and not so rich) folks will collide (literally) in an explosive finale, one in which Daisy will decide who she wants to spend the rest of her life with, Tom or Gatsby.

There is so much screenwriting shit to talk about here, I’m not sure where to begin. Let’s start with this: Gatsby should not have worked as a screen story. It does too many things that should sabotage a narrative, the most egregious of which is having its main character be the least interesting character in the movie. Yes, Nick Carraway doesn’t have jack going on. He’s meager, insular, reactive, boring. The man’s got nothing going on in his life of interest. No intriguing backstory or flaw to talk about. Yet he’s the one taking us through this tale. What’s the deal?

The deal is that he’s a “narrator,” a device that worked quite nicely in the 1925 literary world, but which has since lost its luster. Why? Because at some point someone realized that a narrator who has absolutely nothing to do with anything is probably not main character material. If Gatsby was being written today – ESPECIALLY as a spec – undoubtedly the story would be told through Gatsby’s eyes. This is the man enduring all the interesting shit in the movie. This is the man being active, making things happen. He has the most character development, the most layers. Think about it. He’s the most powerful man in New York, yet the most insecure person you’ll ever meet. He’s draped in the most expensive clothes and vehicles and houses you’ve ever seen, yet he’s unable to see himself as anything other than a penniless nobody. He projects a fantastic life, yet it’s all a lie. He has all this money, but it was all made illegally. It’s no wonder this book has lasted as long as it has. Gatsby is the definition of a fascinating character.

Here’s where the movie ran into trouble though, and I’m not sure if it was entirely the writing or the actors portraying the characters– almost everyone here wilts in the shadow of Gatsby. There’s Nick, of course, who’s only there to offer up exposition. There’s Tom Buchanan (Joel Edgerton) who couldn’t be more of a cliché asshole husband if he tried. And Carrie Mulligan….hmmm, I’m starting to think her time is up. There’s something very…forgettable about her. She has these beautiful sad eyes, which make you want to pick her up and carry her to safety. But she can’t seem to parlay those eyes into any kind of charismatic or memorable performance.

The character who had the most potential within the second string was Jordon, Daisy’s friend, who was always leading Nick around everywhere. However, Fitzgerald created this strange dynamic by which Nick was never allowed too deeply into these characters’ lives, preventing any sort of compelling relationships to occur. Even when the opportunity presented itself, Nick always seemed to pull away from it, as if to say, “Oh, wait, you want me to actually be IN the movie? No, thank you. I’m just going to watch from afar.” It was one giant tease watching him walk around with the flirty Jordan over and over again, only for NOTHING to happen. It almost convinced me that Nick was asexual.

For those interested in discussing structure, Gatsby does offer some talking points. Just the other day we were talking about the “mystery box.” Well, much of Gatsby is driven by the mystery box. The first mystery box is Gatsby himself! What does he look like? Why does he hide in his own parties? Who is this man?? People are constantly talking about him in hushed whispers. There are rumors, guesses, assumptions, all different, all in constant flux.

Once we meet Gatsby, there’s another mystery box (remember – always replace an answered mystery with a new mystery box!). Gatsby seems to want something. We just don’t know what. Eventually, it’s revealed to be Daisy. Finally, there’s one more mystery box, and that is: How did Gatsby accumulate his wealth? This is a big one because the man seems to be one of, if not the richest, men in New York. Everyone wants to know how he became this way.

After all the boxes are opened, the writers realize they need a final force to drive us to the end of the story. Instead of another mystery, however, they choose a goal – for Gatsby to steal Daisy away once and for all, but more specifically, for her to tell Tom that she never loved him. It’s sort of an awkward goal and I’m not quite sure if wanting someone to say a string of words is weighty enough to drive a climax, but it does end up working, as it leads to the most powerful scene in the movie, when Gatsby and Tom battle over Daisy in a steamed up New York apartment.

More importantly, from a screenwriting perspective, there’s something to learn here. You can drive your story forward with a series of mysteries, then insert a late arriving goal to take the story home. Not every movie is going to be Raiders of the Lost Ark, where the goal is established right away. A “late arriving goal” is perfectly fine, as long as you find other ways to keep your readers interested before we get there (in this case, using a series of mystery boxes).

It would behoove me not to mention the amazing use of 3-D here, the best use of it I’ve ever seen. Not so much from a technical standpoint, but from a motivation standpoint. All these other movies seem to use 3-D for the wrong reasons, as a way to make explosions seem more explosion-y. Here, it’s used to bring us back to the early 20th century. I felt like I was inside this world, however exaggerated it may have been. The costumes, the set design, the shots of the cities – it’s all immaculately put together and we’re pulled inside that world, almost to the point where we feel like we could touch it via three dimensions. Add a smashing soundtrack to the mix and this was one of the best pure cinema-going experiences I’ve had in a long time. My only complaint is an over-long second act (did this really need to be 140 minutes long??). But the pure spectacle on display almost made you forget about it.

Script

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

Movie

[ ] what the hell did I just watch?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth watching in the theater for sure!

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: A great reminder that many of the most fascinating characters in history are those steeped in irony. Gatsby is powerful but insecure. Successful but a crook. Irony often creates struggle inside a character, and struggle within one’s self is often the most interesting struggle for an audience to watch.

This is your chance to discuss the week’s amateur scripts, offered originally in the Scriptshadow newsletter. The primary goal for this discussion is to find out which script(s) is the best candidate for a future Amateur Friday review. The secondary goal is to keep things positive in the comments with constructive criticism.

Below are the scripts up for review, along with the download links. Want to receive the scripts early? Head over to the Contact page, e-mail us, and “Opt In” to the newsletter.

Happy reading!

TITLE: While This Offer Lasts!

GENRE: Drama/Suspense

LOGLINE: A federal task force hits the ground running with a sting operation targeting the con man behind the most profitable pyramid scheme is U.S. history.

TITLE: Many Suns for Skeletons

GENRE: Action Adventure

LOGLINE: After the American Holocaust, two naive men discover the infernal necessities to life.

TITLE: All the Devils Are Here

GENRE: Sci-fi/Thriller

LOGLINE: In a world where Alzheimer’s is epidemic and a terrorist group fights for privacy, a reclusive woman investigates her estranged sister’s murder by following a trail of memories some wish could be forgotten.

TITLE: Psychic Hotline

GENRE: Ensemble Comedy

LOGLINE: A rag-tag group of friends go cross-country to hunt down a NYC psychic they believe ruined their best friend’s life.

TITLE: Inhuman

GENRE: Psychological Thriller

LOGLINE: After a radical exorcism leaves a possessed teen in a coma, a psychologist reluctantly helps the clergymen, who performed the rite, wake the child, but soon suspects foul play and finds himself trapped in a secluded monastery with only one person to turn to for help: his newly awakened patient.

Today’s Civil-War script has some good old fashioned amputation in it. The question is, will I want to amputate the screenplay after I read it??

Amateur Friday Submission Process: To submit your script for an Amateur Review, send in a PDF of your script, a PDF of the first ten pages of your script, your title, genre, logline, and finally, why I should read your script. Use my submission address please: Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Your script and “first ten” will be posted. If you’re nervous about the effects of a bad review, feel free to use an alias name and/or title. It’s a good idea to resubmit every couple of weeks so your submission stays near the top.

Genre: Horror/Suspense

Premise (from writer): A group of graduate history students on vacation touring Civil War battlefields are terrorized by a motley crew of Confederate re-enactors who harbor a 150 year-old secret.

About: This script won the Amateur Offerings post from a few weeks ago.

Writers: Darren & Evan Brooks

Details: 108 pages

When I sent The Still out in the newsletter, I received a harried e-mail from one of our OTHER readers who’d written a “Civil War Reenactment” script of his own. He was terrified that the similar subject matters would render his script useless. The truth is, I see a couple “Civil War Reenactment” screenplays a year. The bad news about this is that there’s competition, and since everyone hopes to have that original one-of-a-kind idea, it can be heartbreaking when you realize you’re not the only kid on the block. The good news is, I’m yet to find a writer who’s figured it out yet. There are a lot of story possibilities to explore with this unique subject matter, but no one’s really nailed it. In fact, no one’s really come close. So when people started responding to The Still in Amateur Offerings, I hoped we’d finally found “the one.”

Graduate student Anna, a history buff, is taking a group of friends along for what she hopes will be the experience of their lives – a real live Civil War reenactment! But not the kind that a group of backwoods rednecks puts together after a night full of moonshine. This is one of the biggest reenactments in the country. Thousands will be involved.

The problem is, no one really wants to come with Anna to do this. Fellow graduate student and boyfriend Thomas is just trying to keep Anna happy. Thomas’s brother Spencer is more interested in keeping a continuous alcohol buzz for 72 hours. The only one who’s remotely intrigued is the snobby Ebay-obsessed Dustin, who thinks they’re going to find a bunch of authentic Civil War memorabilia in the battlefields and sell it to Pawn Stars or something.

For some strange reason, the only one participating in the actual battle is Thomas. Anna suits him up, sends him to the battlefield, and promptly watches him “die” on the third wave of shooting. However, maybe “die” shouldn’t be put in quotes. Thomas is mysteriously dragged away while a dark liquid trickles out of a hole in his uniform. I knew these guys strived for realism, but this seems a bit excessive, no?

Later that night, Anna gets worried when Thomas doesn’t come back to the hotel. After voicing her concern to the local cops, Spencer and Dustin head into the night to start looking for Tom, who they think may have gotten lost in the woods. Why they believe they can find him in the dead of night inside of 1000 square miles of forest is beyond me, but hey, I’ll go with it.

They don’t find Tom, but they do stumble upon some authentic Civil War canteens Dustin believes he can sell. They then ALSO run into some Civil War reenactors who don’t embody the ‘re’ very well. These guys look like the real deal – decrepit, gaunt, dirty. And they play dirty too, grabbing our poor friends and taking them back to dark rooms where legs will be amputated!

Back at the hotel, Anna twiddles her thumbs and wonders where the hell everyone is. A little later we learn these baddies are from the ORIGINAL Civil War, and have built some sort of “fountain of youth” machine so that they never die. What remains of our grad student group will have to escape these freaks before they wreak their havoc on not just them, but on all the rest of the rest of the reenactors as well!

Okay, The Still started off great. The writing was very descriptive. It set the time, the place, the mood. I felt like I was there. For those who just picked this up and read the first ten pages, I can see why they’d vote for The Still above the other scripts on the list. But the further down the rabbit hole The Still goes, the less traction it maintains, losing a grip on its story, and making you wonder if there was ever a story to tell in the first place.

Take Anna. She’s presented as our main character. This whole thing was her idea. Yet Anna is the least active character in the story! She sits back at the hotel the whole time waiting for information to come in. That made me wonder who the main character was. Dustin and Spencer are probably the most active, but neither of them screamed “main character.” If a reader leaves your story not knowing who the main character was, you have a lot of screenwriting explaining to do.

Then there’s Thomas, the boyfriend. Thomas gets shot during the battle and taken. This is the inciting incident for our story. Our characters must solve the mystery of “Where is Thomas?” Except after a couple of scenes of searching, Thomas becomes an afterthought. And while on the one hand I understand this, because our characters have been attacked by psychos and thrown off-course, the lack of any defining goal pushing the narrative forward left the story spinning out of control. After awhile it was just a bunch of chickens running around with their heads cut off.

Once that happened, I wasn’t sure what this movie was about anymore. Was this a “Texas Chainsaw Massacre” or “Deliverance” type film? If so, we needed that super memorable freaky moment that moviegoers will never forget for the rest of their lives. The “squeal like a pig!” scene. Because that’s what those movies do. They terrorize you with the unimaginable. I didn’t see that here. I didn’t see any clear genre. Which is what led me to believe that these were two really good writers who didn’t outline their script.

And we were JUST TALKING about this the other day with “Gone Girl.” If the purpose of your writing is to figure out what you’re writing as you go along, your story will start to wander. It just will. We, as readers, will sense that you don’t know where you’re going. And losing confidence in a storyteller is no different than losing confidence in a guide in the woods. At a certain point, we’re going to stop listening to you.

Moving forward, I would try to figure out what this movie is. Is it a horror movie? Is it torture porn? Is it a mystery? “Monster in-a-box?” Because I don’t think it can be all those things. That’s a big part of what’s contributing to the confused narrative. Once you have that figured out, decide who your main character is and make sure they’re driving the narrative. This is Anna’s boyfriend who’s missing. She should be going out after him. Not these other guys. Or at least they should all be going out together. Come to think of it, you may want to switch roles and have Anna be the one who’s kidnapped and have Thomas go after her. There’s something very non-threatening about a strong grown man being taken. A helpless young woman though? We’re going to want our hero to save her.

Finally, make sure the goal always stays in the forefront. Your characters will get derailed. They will get accosted, beaten, lost, etc. But their focus should still be on the prize – finding Thomas (or finding Anna!).

I’m a little disappointed in this entry because it started off strong and then completely lost its way. Writers continue to believe that if they write pretty, it will solve all their problems. Readers don’t care about prose. They care about a good story. I mean, look at Charles Ramsey, the man who saved those girls in Cleveland. I wouldn’t place him in an “Eloquent Speech” contest anytime soon, but man did he tell a great story.

Once again my friends – outline. It helps you discover all your problems before you run into them.

Script link: The Still

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Use your story’s theme and setting to figure out your protagonist’s fatal flaw. Remember what a character flaw is. It’s that “thing” that’s been holding your character back his/her whole life. Your story, then, should challenge that flaw, and in the end your hero should either overcome it or succumb to it. In this case, we’re exploring the Civil War. So the writers of “The Still” wisely make Anna a history buff whose flaw is that she’s obsessed with and stuck in the past. She doesn’t focus on the present or the future, and it’s hurting her relationship with Thomas. I’m not going to say they executed this flaw to perfection (like a lot of things, I think it got lost as the story went on), but it was the right idea.

It’s no secret that I have a Hollywood crush on JJ Abrams. I think he’s the smartest guy out there right now, building up his brand, taking on some of the biggest franchises in town, including my favorite franchise of all, Star Wars. He’s also exploring his original creative side via numerous TV shows and producing attachments. He created the kick-ass Alias, the best TV show of all time, Lost, and his company keeps snatching up all the cool sci-fi specs in town. Bad Robot even optioned Stephen King’s 11/22/63 recently. Abrams is starting to make guys like Spielberg (ironically, his idol) look like out of touch dinosaurs.

If a day ever comes where I spin Scriptshadow into a production company, I will meticulously study and copy every single move JJ Abrams has ever made, as a writer, as a creator, as a director, and as the head of a production company. The time may have passed me by for selling a script at age 25 that the biggest actor in the world signed up for (Harrison Ford in Regarding Henry). But as far as everything else, as far as how he runs his business, what projects he and his company attach himself to – yes, I’ll be trying to emulate that.

How does that tie into today? Well, I feel Abrams gave a great TED talk a few years ago, and the more I’ve learned about screenwriting since that time, the more I realize how powerful and important his talk, centering on one particular element of storytelling, was. In screenwriting, our job is basically to make sure that the reader wants to turn the page. It’s a simple yet, at the same time, impossibly difficult task. It takes practice and skill and talent to make someone want to read your script all the way through. If I’m being honest, 60% of the time I read a script, I don’t even want to turn the first page. I’m already sensing that the writer doesn’t know how to intrigue me, tempt me or bait me. The writing and story and situation are dry by the time I hit the middle of page 1.

Luckily for screenwriters, the reasons for this aren’t that the writer is “bad.” It’s almost always because they don’t know how to tell a story yet. They haven’t studied (or learned through trial and error) the basic tenements of dramaturgy, the ways in which you weave a tale so that the reader keeps needing more. For example, if I were to tell you a story about my day and started with the bumper-to-bumper traffic I endured on my way to work, then segued into not being able to find a parking spot because they were re-paving the lot, then hit you with the astounding tale of getting a “mean” look from my boss as I stumbled into the office five minutes late, there’s a good chance you’ve already nodded off. But if I started this same story with the proclamation, “Holy shit! The most insane thing happened to me at work today. You’ll never believe it!” then went through that exact same story, you’re not bored anymore. That’s because you’re now anticipating this “insane thing,” and you’re along for the ride until you hear it. It’s a very basic storytelling trick. And since most writers out there don’t study screenwriting or storytelling or creative writing or drama, they simply don’t know this, as well as all the other tricks we storytellers use to keep our audiences entertained. Which is why so many screenplays out there are so boring.

In JJ Abrams TED speech, he addresses one of the most powerful tools one can use to keep the audience interested – that of mystery. Now while mystery is a tool I’ve brought up before, it wasn’t until re-watching JJ’s speech that I realized how important it was. Without mysteries (small, medium, or large) there’s no real incentive for the reader to keep reading. If there’s not something they’re trying to figure out or find an answer to, then the story loses its mystique, its power.

The thing is, I’ve always had a hard time making this term categorizable, forcing me to say things like, “Just make sure you have a lot of mysteries in your script.” What I love that JJ’s done here is that he’s “tangiblized” the term of mystery by identifying it as the “mystery box.” This way it’s a “thing,” rather than a method. And once I saw it as that, I realized that you can more readily and methodically implement it into your story. Every story needs mystery boxes!

Typically, you start with one giant mystery box. This is the box that drives the overall story. Take The Hangover for example. “Where’s Doug” is the mystery box. There are certainly other reasons why The Hangover is so fun (it’s funny, the stakes are high, the characters are great), but the mystery box that’s always at the back of our mind – the one we won’t be satisfied until we get an answer to – is “Where the hell is Doug?”

Looking back at JJ’s body of work, you’ll find mystery boxes dominating all his movies and TV shows. With Lost, it’s “What is this island?” With Alias it was the mystery of the Rambaldi. In Mission Impossible 3, it was the “Rabbit’s Foot.” It’s no coincidence that JJ incorporates these mystery boxes into his plots. They hook you right away, and keep you around until they’re opened.

Once you have the big mystery box, it’s your job to set up a number of medium to smaller mystery boxes. You intersperse these throughout your script, so not only is the reader wondering what the hell’s in the big box, he wants to know what’s in these small boxes as well. While I see a lot of writers (either purposefully or on accident) incorporating giant mystery boxes to drive their story, I see far less small mystery boxes that get us through a scene or a sequence. For example, if a guy and a girl sit down at a diner and just start talking, it’s not nearly as interesting as if one of them starts the conversation with, “I have something important I want to tell you,” and then you withhold that important information until the middle or end of the scene. Mystery box!

Abrams uses Star Wars as an example of how to use mystery boxes, and it’s a good example. But you can pull out any popular story and find a fair share of mystery boxes packed inside. Gone Girl (which I reviewed yesterday) is jam packed with mystery boxes. Who kidnapped Amy? Why doesn’t Nick have an alibi for the time of the murder? What was he doing at the time? What’s this mysterious phone in his pocket he never answers? In fact, the book only begins falling apart when it runs out of mystery boxes at the end. There’s no more mystery and therefore no “presents” left to open. Amy shows up and starts living with Nick. They bicker a lot. We’ve lost interest.

So how do you incorporate mystery boxes into your own stories? Well, imagine an audience sitting down to watch your movie in a theater. Then imagine a giant shelf next to the screen. Think of this shelf as the “Shelf Of Teasing.” It’s where you’ll place those big fat mystery boxes. As the audience is watching their movie, they can’t help but keep looking over and seeing these irresistible mystery boxes taunting them. They need to keep watching until all of them are open.

Now there are few rules to these mystery boxes that you’ll want to follow. First, if you take away the giant mystery box, the one with the biggest question, make sure to replace it with another mystery box equally as interesting. In Lost, one of the big mystery boxes is this hatch that they find on the island. As soon as they show you what’s inside that mystery box, however, they replace it with another. There’s a computer in the bottom of the hatch where a series of mysterious numbers need to be entered every 8 minutes. Why? We don’t know. NEW MYSTERY BOX!

In addition to this, make sure each mystery box is as mysterious and interesting as possible. A boring mystery box is no different than no mystery box. For example, in Lost, if you would’ve replaced the hatch Mystery Box with, say, a mystery box asking why the room was yellow, the reader/audience won’t give a shit.

Finally, try to make sure there are ALWAYS BOXES on the “Shelf of Teasing.” They don’t need to all be amazing or huge. They just need to be enough to keep the audience curious. I’d venture you should have anywhere between 2-6 mystery boxes on that ledge at a time, depending on the kind of genre and story you’re telling (certain stories, like “The Sixth Sense” will depend more on Mystery Boxes than, say, “Silver Linings Playbook”).

Now before you go back and start incorporating mystery boxes into your script, watch a few of your favorite films and take note of how they use mystery boxes. Familiarize yourself with the process. And remember, always try to have one final lingering mystery box until the very end. As long as your audience is wondering how that final mystery is going to be answered, they will keep reading/watching. Good luck!

David Fincher swoops down to explore his next potential directing assignment. So I decided to check out the book.

Genre: Thriller

Premise: Told from two different points of view, a man’s wife goes missing and he becomes the prime suspect.

About: 41 year old Gillian Flynn is a former Entertainment Weekly TV critic. She’s written three novels, with “Gone Girl” being her most recent. The bestseller got a bump a few months back when David Fincher expressed interest in adapting the book into a film. It’s unclear if he was just circling it or is now officially developing the screenplay.

Writer: Gillian Flynn

Details: Way more than 120 pages long

Why the hell am I reviewing a book? Well, first of all, to prove that I can read books! There’s this rumor going around that I can only read text in courier 12 point font, and that said font can never eclipse 4 lines of continuous text at a time. There have been stretches in my life where this is true. But when someone like David Fincher comes along and says he likes something, my book-reading juices start flowing. And this juice is not made from concentrate.

I can’t remember a single project Fincher’s been attached to that has been bad. Most of the time the script for the project is at least a [xx] worth the read and usually an [x] impressive. What I love about Fincher is that he’s one of the few guys out there willing to take chances. While directors like Jon Favreau and Ridley Scott are pretty much playing it safe, Fincher always wants to push the envelope. Gone Girl is no different. This book is a freaking wild ride. It does stuff I’ve never seen in a novel before.

However, let me warn you, this book is one giant spoiler. There’s a shit load going on and it has one of the best twists I’ve ever seen in a novel or movie. If you have any interest in reading this book or seeing this movie, do not read this review, because I’m going to get into all the spoilers. You’ve been warned.

The first 40 or so pages of Gone Girl are pretty boring. In them, we meet Nick and Amy Dunne, former Manhattanites who have to relocate to Nick’s home town in Missouri when he loses his job. Nick has since used Amy’s money (that comes from her wealthy parents, authors who made a fortune writing books about her childhood) to open a bar that only barely breaks even, and is one of several factors that have driven these two lovebirds apart.

You see, Nick and Amy used to really love each other. Like “love has no boundaries” love. The kind of love Double Rainbow guy would have for a Triple Rainbow. We know this because interspersed between Nick’s present, is Amy’s past, told in firsthand through her journal entries. It’s a devastating dichotomy as we cut back and forth between the wonderful love story Amy offers up and the cold clinical realization of their relationship now, told through Nick’s POV.

Just as we’re getting to know these two, something unthinkable happens. Someone breaks into Nick’s house while he’s away and takes Amy. The crime scene is violent and bloody and while there’s certainly a chance Amy’s still alive, it doesn’t look good. What also isn’t looking good is Nick. You see, Nick fell out of love with his wife a long time ago. And even though she’s been taken, there’s something deep inside of him that doesn’t really care. And therein lies the problem. When Nick goes on national TV to ask for his wife back, there isn’t a shred of emotion in his voice. To any and everyone who watches Nick, they have no doubt that he killed her.

Nick looks for solace from his twin sister, Go. She’s the only one who believes him. But even that’s looking shaky as Nick can’t give the cops an alibi for the time his wife was taken. The book then keeps cutting back and forth between Nick’s worsening nightmare and Amy’s love-sick journal. However, as the story continues, and the journal’s timeline catches up to the present day, we see that Nick has been hiding some secrets. He’s got some demons. And those demons are so bad that as early as last week, Amy went to buy a gun to protect herself from him. It’s looking really bad for Nick. Even we’re wondering if he did it.

And then comes the twist of all twists.

It was a lie. Every word we heard in Amy’s diary was a lie, right down to the personality we thought we knew for the last 250 pages. Amy isn’t bubbly and sweet and good and caring. She’s evil. She’s the definition of hate and bitterness. The diary was a plant, something she’d been working on for a year to lead up to this moment to work as the smoking gun that would send her husband to the chair for her murder. Why would anybody do something like this? For that you’ll have to read the novel. But let’s just say that Amy is the single most vindictive person on the planet.

Once we realize we’ve been scammed, we realign ourselves with Nick, hoping against hope that he can find Amy to prove he didn’t kill her. This task is getting harder by the second as Amy leaks sordid details of Nick’s past anonymously to the press, which means that the cops are probably going to pounce and arrest him soon. Only time will tell how or if Nick will get out of this. If he doesn’t find out how his girl got gone, he’s going to be gone himself.

Okay, I just have to say it. The twist here fucking ROCKED. I mean I was blown away. For 250 pages, we’re given a person, a backstory, a personality, someone we like and trust. We love Amy. To see the “mid-point twist,” then, where we realize it was all a setup? That she made up this version of herself and was really the complete opposite? It’d be like if your best friend of 20 years showed up one day and revealed that he was a completely different person. The way that twisted the story, realigned our sympathy, reversed the polarity of who we were rooting for? It was nothing short of genius.

And really, that’s where a lot of the genius occurs here – the way Flynn frustrates us with who we’re supposed to root for. She makes us hate Nick and love Amy at the outset. Then she shows us Nick’s point of view, and we like Nick and hate Amy. Then we find out something about Nick, and we hate him again, falling back in love with Amy. This constant “switching of allegiances” was masterful, and something we just don’t see in movies, probably because we don’t have enough time. Being yanked back and forth between these two is a big reason this book was able to stay so interesting for so long.

Also, Flynn does an amazing job keeping you guessing who the killer may be. At different points we wonder if Nick himself did it. If an old friend of Amy’s did it. If someone from town did it. At one point we even wonder if Nick’s twin sister is secretly in love with him and killed Amy to get her out of the picture. Flynn is really good at making you think you have things figured out, only to pull the rug out from under you.

What makes Gone Girl so difficult to read though, is that it destroys all hope you have in humanity and relationships. Amy is a vindictive bitch who will go so far as to stage her own murder to take down her husband. And Nick just doesn’t care about Amy anymore. These were two people who were madly in love. So to watch them become these hateful human beings, to see the severity of their relationship’s collapse, kind of makes you want to slit your wrists. It’s really depressing!

But despite snagging an elusive [xx] genius rating through the first half of the story, Gone Girl completely falls apart in its final act. Embarrassingly so. Running out of money and options to survive, Amy comes back to Nick. Amidst all the news coverage and the circus surrounding her disappearance, she just starts living with him again. Amy points out that because they’ve gone through what they’ve gone through, they can’t possibly be with anyone else. They may be miserable, but they’re stuck with each other. And that’s how the book ends, with both of these miserable people deciding to stay together and hate each other til the day they die.

WHAT???

I was so upset with this ending that I went online and researched Flynn to figure out why she would do such a thing. What I found made everything clear. Flynn, it turns out, doesn’t outline. She just writes whatever comes to her. WELL JESUS! NOW IT MAKES SENSE! She wrote a bunch of crazy shit then had no idea how to pay it off. This is EXACTLY how the last act felt. Like someone who had no idea how to end their story.

Which begs the question: How the hell does Fincher plan to adapt this? Why would you adapt something if the greatest thing about it is un-adaptable? We’re fooled by a journal, by a character writing directly to us, who it turns out is lying to us. How does one pull that off in a movie? We have to see Amy. We must show her writing these entries. And since her writing is a façade, something she’s making up, one would presume we’d pick up on her deception as it’s happening.

I suppose you could tell the first half in Amy’s voice over, with her journal entries read out loud over the life she’s describing, but I’m just not sure that would be as convincing (or even make sense). If they do decide to make this, though, I’d look into making the genius twist the ending, as opposed to the mid-point. You don’t really have time to go through an entire relationship and then an entire aftermath of the twist anyway, in a film. This way you’d also eliminate that dreadful ending. That would be really cool if they figured it out, but it will be a challenge.

What an unforgettable reading experience “Gone Girl” was. It has amazing highs and devastating lows. It has “holy shit” twists and an indefensible climax. It’s such an imperfect piece of art, it’s hard to categorize. But I’m not surprised Fincher became interested. It’s so dark and different. If there’s anyone who can figure it out, it’s probably him.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Know your ending before you start your story, if possible. You can come up with all the cool twists and turns in the world, but if you can’t bring everything together in the end, it won’t matter.