Genre: Period

The Flight of the Nez Perce is a spec script that, by Hollywood standards, should not work. It’s more than 130 pages. It’s an extremely violent period piece, where half the dialogue is subtitled. It also asks for a cast of hundreds, and probably couldn’t be produced for less than $120 million. Normally, these are all choices I would suggest screenwriters avoid. And yet, I still hope that a miracle happens, and this movie gets made.

I confess the main reason I picked up this script was because one of the author’s other works, Desperate Hours, currently holds the No. 1 spot on Carson’s top 25 list. But, after I finished it, I read it a second time because I loved it. Despite its flaws, The Flight of the Nez Perce is an excellent piece of writing. Let’s find out how this script breaks through the chains of industry expectations.

The year is 1877, and it’s a time of cultural unrest in America. The Civil War may be over now, but there are still people in this country fighting and shedding blood, to protect their way of life. After living in balance with the natural world for hundreds of years, everything is changing for the Indian people. The white men have come to these shores to stay, and their presence spreads across the land like a sickness. The symbol of the white man’s reach is the steam locomotive, which the Indians call “the iron monster.” The Indians have come to learn that, when they see thick plumes of train smoke rising above the trees, it means the white man has arrived, to take them from their homes. Sometimes never to be seen again. Through their actions, the white men stir a combustible mixture of fear and anger inside the Indians’ hearts. Until one day, beside the waters of the Little Bighorn River in Montana, the match is lit.

The Battle of the Little Bighorn arguably becomes the worst Indian-related massacre in American history. Chief Sitting Bull and his Sioux tribe kill Captain George Custer and all his men, winning a major victory against the U.S. army. The outcome of the battle does a couple noteworthy things. First, the army takes a more aggressive stance on handling Indian affairs. As General William Sherman says at one point, they cannot afford another Little Bighorn. The other thing that happens is, warriors from other Indian tribes hear of Sitting Bull’s victory, and become even more determined to defeat the white man. Basically, relations between the two cultures just got a whole lot worse.

This all adds up to bad news for Chief Joseph and his Nez Perce tribe, which has lived in relative peace, in the Wollowa Valley of the Pacific Northwest. Joseph sees war as a failure of mankind, and will do anything he can to stay clear of it. This seems impossible, though, when Red Grizzly, a Nez Perce warrior, brings news of the Little Bighorn massacre. Red Grizzly wants to follow Sitting Bull’s example, and take the fight directly to the white men. Joseph turns down the suggestion, not wanting to put the tribe in harm’s way. But Joseph soon understands he can’t stop the inevitable.

Soon after Little Bighorn, General Sherman receives orders from the U.S. president to remove the Nez Perce from the Wollowa Valley, and send them to a reservation in Idaho. And, if the Nez Perce refuse to leave, then the army has permission to use any means necessary. Why is the government suddenly interested in the Nez Perce? Aside from wanting to keep the Indians under control, it turns out there could be significant gold deposits right under the tribe’s feet. And the white men want to get their hands on that gold at any cost. So, Sherman sends Civil War veteran General Howard and his regiment to run this campaign against the Nez Perce.

Meanwhile, tensions are heating up near the Nez Perce settlement. The white people have built a town nearby, and it’s been difficult for everyone to be neighbors. For example, one of the tribesmen, Eagle Rock, comes across a riderless horse during a walk in the forest. Eagle Rock tries to befriend the horse, thinking it doesn’t have an owner. But it turns out that it belongs to an unfriendly white man named Larry Ott. Larry sees Eagle Rock touching his horse, and he doesn’t like it one bit. Because they don’t understand each other’s language, a fight breaks out between Eagle Rock, Larry, and Larry’s friends. Eagle Rock is shot to death.

Eagle Rock’s murder sparks rage among some of the Nez Perce warriors. The warriors, led by Red Grizzly, go out one night to kill Larry Ott for revenge. The only problem is, once they get to Larry’s cabin, no one’s there. Larry probably knew he was in trouble and left his home for good. Not happy with this situation, the warriors find another white home close by. At this point, it doesn’t matter who they kill, as long as their victims have pale faces. The warriors kill several men at this house, and Red Grizzly rapes a young mother. The mother escapes and notifies the authorities of the horror that just happened. She also asks General Howard to kill all the Indians.

Chief Joseph and the rest of the tribe learn of the atrocities that Red Grizzly and the other warriors committed. Joseph takes these men into custody and plans to deliver them to the white people, so they may determine the punishment. The next morning, Joseph meets with white army, to turn over the warriors and talk about moving his tribe to Idaho. Unfortunately, during this meeting, a snake startles one of the Indian’s horses. When the horse rears up, one of the U.S. soldiers thinks it’s an attack, and fires at the Indian sitting on the horse. This causes a bloody battle to break out. In the end, the white men are soundly defeated, and the Nez Perce didn’t suffer a single casualty. It’s a victory, but the damage is done. The Indians think there’s no chance for peace now, so they begin a 1,300-mile run for Canada, in hopes of finding sanctuary with Sitting Bull’s tribe. General Howard and his army have no intentions of letting the Nez Perce escape, so they chase them every step of the way. The Nez Perce win several battles on their flight North, using tactics that are studied to this day. But because their hardships become too much to take – the loss of life, the starvation – they finally surrender to the white men, just forty miles away from the Canadian border.

There are a lot of reasons why this script is so good. One of the biggest reasons is that the author knows how to create empathetic characters. Without empathy, the character probably won’t connect with the audience. This doesn’t mean the character has to be likable at all times. But, it does mean that we, as readers and viewers, should be able to see the world through that character’s eyes. I think the writer accomplishes this goal. For example, it would’ve been easy to make the U.S. Army the indisputable villains. But the author is too generous to leave it at that. He paid special attention to the army’s high-ranking officers. I came to respect General Howard, in particular, because he eventually grieved for Joseph and the Nez Perce, and wished he could atone for his behavior. That kind of nuance is missing in a lot of antagonists I’ve seen. So when I find one that’s still in touch with his humanity, it stands out. Having said all that, my favorite character turned out to be the most likable of all. Chief Joseph brought tears to my eyes. He meets my definition of a good man. He wanted to live the rest of his life with his friends and family in peace. The last thing he wanted to do was hurt another human being, but he was willing to, if that’s what it took to save his people. Even in his defeat, he was dignified, courageous, and true to himself. Joseph has a place in my heart, and he’s welcome to stay there as long as he wants. I’d love to see more scripts use characters like this.

Another element that made this demanding script more enjoyable was the massive scope of the story. We get epic battles, forbidden love, fellowship, betrayal, and, just when we need it most, mercy. And it all takes place on the vast, untamed landscapes of the American West. So, if there are some elements in your script that are obscure or complex, you can balance those things with a few mainstream qualities. Especially if you’re writing a period piece, it can’t come across as a dusty history lesson. The audience, above all, needs to be moved and entertained.

Perhaps the most important reason why this script works so well is the way it’s structured. A lot of scripts these days hit the ground running, and they never stop. The writer, E. Nicholas Mariani, structures his scripts in a way I don’t see many other people use. He implements a slow buildup that eventually explodes into a breathtaking third act. In “Flight,” he uses the first act to introduce us to the many people of the Nez Perce tribe. He also introduces us to the U.S. Army, and explains why they plan to move the tribe off their land. A lot of story points are setup in the first act, so the first 20 or 30 pages are a bit slow. But Mariani is willing to take that risk because he knows the ending will mean more, if we feel something for these people. The next two acts are constructed around the battles between the Nez Perce and the U.S. Army. The beauty of this approach is that each battle sequence requires greater and greater sacrifices from both sides of the war. The losses of the Nez Perce become more meaningful, as the order of deaths starts at the less important people, and moves up to the most beloved. The environmental obstacles also become more dangerous with every step. In one scene, the Nez Perce have to climb a mountain during a mudslide. And then in a later scene, they have to fight the army in a blinding snowstorm. The conflict is elegantly designed like a rollercoaster; it’s always moving up the hill. And with the third act, we come careening down the other side.

Act three is what really made the script for me. If you’ve ever taken an American History class, you probably know what happened to the Indians. The story of these people is almost unbearably sad, and that’s how I felt when I watched Joseph surrender his tribe to the army. By this point, the Nez Perce are completely exhausted and miserable. After the final catastrophic battle, the “flight” is over and they lost. When Joseph gives his immortal speech of surrender, I felt his pain deep in my bones, because Mariani structured his script to build up to that final climax. It was glorious to behold. Because of this script, I find myself supporting the slow build. If it’s done right, it helps setup the ending more effectively than a shallow first act would.

Of course, no script is perfect, even this one. I’d argue that the dialogue could use some more sepia tones. Like his other script, Desperate Hours, the characters sometimes sound too modern for the times they live in. My humble suggestion is to focus a rewrite on giving more period flavor and texture to the voices of these amazing people.

And, of course, there’s the issue of the large cast. I’m honestly torn on this one. I kept a head count, and there were at least thirteen characters introduced by name in the first five pages. In most cases, I’d highly recommend keeping the cast list down to five or six major characters. Not only is it hard for the reader to keep track of so many people, it’s hard for the writer to develop all of them with such a limited page count. But this script has the one exception for a big cast that I can think of. The third act would not be as good without it. It just wouldn’t. The power and devastation of the third act is largely achieved from realizing how many people died since the first page. If the cast had been smaller, the effect would have shrunk, as well.

In the end, The Flight of the Nez Perce was more than just another script to read. It was a full-blown experience. I was so tied up in the story that, when I finished the last page, I felt emotions I couldn’t quite explain. I was bruised, heartbroken, and appreciative all at once. Is there a name for such a thing? Yes, there are problems in this draft worth fixing. But, to paraphrase Maya Angelou, the problems aren’t what I’ll remember. What I’ll remember is the way this script made me feel. Unless something better comes along in the next couple months, this is my script of the year.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: If your concept is expensive and noncommercial, be very sure that it’s an idea you’re passionate about. The Flight of the Nez Perce was on the Black List two years ago and, to my knowledge, hasn’t sold yet. Sadly, it’s not too surprising because the logline is a hard sell. In his 2010 Black List commentary, Carson himself said that this script “takes the cake for being the most boring sounding script on the list.” And yet this script is amazing. The author obviously had a strong feeling about the idea and put everything he had into it. So, at the very least, this is an incredible calling card script. But if your goal is to write a spec that’s an easy sell, it makes sense to use a concept with a mainstream hook and a modest budget.

Genre: Period/Mystery/Thriller

Is anyone still here? I got a lot of comments yesterday from people saying they were never going to read Scriptshadow again. Because I gave Looper a bad review. I can’t help if I thought the writing was bad. Though I admit my morbid fascination with Joseph Gordon-Levitt’s face maaaaaay have prevented me from picking up on some key plot points early on, mainly about this Rainman character, who I’m still confused about. But we can’t go backwards. We must go forwards. And in going forwards, we must go backwards, back to 1867.

I soooooo wanted to love this script! It was not only my favorite first 10 pages of the Twit-Pitch contest, but the writer, Nikolai, is a hardcore Scriptshadow Twitter follower. The man retweets my tweets like cray-cray, and is a huge supporter of the site.

The problem Nikolai runs into with The Tradition is one I’ve become more and more familiar with over the last few months. Nikolai is an amazing writer. But he isn’t yet an amazing storyteller. What I mean by that is that the descriptiveness of The Tradition is TOP NOTCH. I can’t think of any other screenwriter who could make me feel like I was in 1867 London more than Nikolai. Take this simple description of a character as an example: “A fusty old SOLICITOR with great big grey pork chop sideburns and pince-nez glasses is shuffling through papers like a catfish.” I jumped to a random page and found that. That’s how everything is written in The Tradition. We are pulled into this world due in whole to the amazing writing. No question about it.

But pulling us into a world has nothing to do with telling us a story in that world. That’s a completely different skill. And unfortunately, there’s isn’t much of that skill shown in The Tradition. It feels like a story that could’ve taken place in 30 pages, stretched out to 116. That’s what was so frustrating. One of the reasons The Tradition got me in its first 10 pages was because something HAPPENED. A man is running from a mysterious tribe of Polynesian boys. He’s captured. Killed. It was an exciting first scene. But after that scene, shockingly enough, little to nothing happens for another 100 pages. It didn’t feel like a story was being told so much as a series of mundane events was being meticulously chronicled.

The Tradition starts off with that early great scene, then flashes forward 50 years to England circa 1867. A young and beautiful woman, IDA, has just buried her father, only to realize that he’s left her in a boatload of debt. Her once illustrious lifestyle is torn from her in order to pay this debt, and she soon finds herself slumming it up as a seamstress to make ends meet.

That job falls to the wayside soonafter, and Ida is less than a month’s rent away from seriously considering prostitution. So lucky her when she’s spotted by the son of a royal Lord, John, who asks her and her roommate to come work for him in the countryside. Away they go, along with many other women and children, and all of a sudden Ida has a job, a future…Things aren’t looking so bad!

In the meantime, we meet Arthur, John’s younger brother. Arthur’s the family outcast, mainly because he doesn’t agree with a secret tradition the family goes through every year. We’re only given vague hints as to what this tradition is, but it’s evident that wherever Ida and all these other women are being taken, it isn’t going to end well.

Which is strange because the mansion Ida and the others arrive in appears to be a dream come true. They get new clothes to wear, yummy food to eat, lovely beds to sleep in. The only downside seems to be that the Lord is a little sleezy and John is a bit of an asshole.

It’s at this point, unfortunately, where the script really starts to lose itself. The stuff that goes on at the house – which is essentially nothing – goes on forever. The story is relegated to people wandering through halls, occasionally bumping into each other, followed by some talking. Nothing is actually happening. Nobody’s trying to do anything. My guess is that Nikolai was trying to rest his story on this impending sense of doom in this house, and I admit to being a little curious as to where it was all going. But there was so little drama and conflict leading up to the final act that I became bored.

You need SCENARIOS in your screenplay. You need intriguing mini-stories with their own goals and complications and mysteries and conflicts and characters pushing up against other characters. For example, maybe Ida is given the job to prep each woman before taking them down to a mystery room. She has to make sure their dress is perfect, their make-up is right, that they look as good as they can possibly look. She does this. However, once she brings these women downstairs, a mysterious assistant takes them and she never sees them again. She begins to get suspicious and starts looking into it, putting herself in danger. Now, at least, we have a woman doing something as opposed to obvliviously stumbling around the castle hallways occasionally running into someone and talking to them.

That’s the difference between writing and telling a story. When you’re writing, you’re trying to think of the best way to describe what’s happening in the moment and figure out what each character is going to say to each other right now. When you’re storytelling, you’re looking to construct scenarios full of mystery and tension and drama and conflict and danger that extend beyond the immediate scene.

I started getting worried after those first ten pages. After we set up that Ida was on her own, it just took forever to get her to the castle. I don’t remember the exact page number but I’m pretty sure it happened after page 45. We should’ve been on our way to that castle by the end of Act 1, page 25. Remember guys, your story is almost always playing slower than you think it is. So while you think you need this long scene showing how difficult it is for your character to be out of a job, we’re waiting for the next interesting thing to happen. With The Tradition, I felt like I was always waiting too long for that next interesting thing to happen.

Character-wise, there wasn’t much going on with anyone other than Arthur, the black sheep brother who refused to partake in the tradition along with the rest of the family. I liked that Nikolai tried to create a flaw within him, that he was basically a coward. But the coward flaw is always difficult to execute because you risk the possibility of the audience thinking the character’s a p*ssy and being annoyed with him. I have to admit, that’s how I perceived Arthur. Instead of rooting for him to stand up for himself, I kept thinking, “Grow some balls, buddy. Jesus.”

The character we should’ve been exploring was Ida. She started out strong, with this crippling scenario of losing her father and her home, but there wasn’t enough going on inside of her to keep my interest after that point. We need some sort of conflict inside someone that needs to be resolved, whether it be a flaw or something from their past or whatever, and that wasn’t here. Jodie Foster had both a past and a flaw to overcome in Silence Of The Lambs, for example. She had the lambs. She also had an obsession to show that a little girl could do the job just as well as the big boys. Ida’s just sort of naively going wherever the story takes her.

For these reasons, I couldn’t get into The Tradition. But I have high hopes for Nikolai. He’s obviously an excellent writer who now needs to become a storyteller.

Script link: The Tradition

What I learned: Repeat after me – “Screenwriters are not writers. They’re storytellers.” “Screenwriters are not writers. They’re storytellers.” “Screenwriters are not writers. They’re storytellers.”

Genre: Sci-Fi/Drama?/Horror?/Supernatural?

Premise: (from IMDB) In 2072, when the mob wants to get rid of someone, the target is sent 30 years into the past, where a hired gun awaits. Someone like Joe, who one day learns the mob wants to ‘close the loop’ by transporting back Joe’s future self.

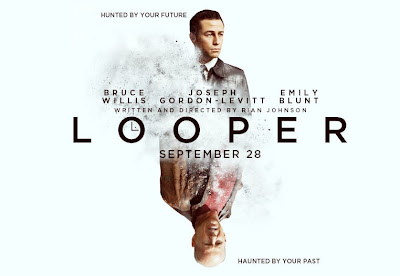

About: Rian Johnson, who broke onto the scene as a writer/director of the Joseph Gordon-Levitt starring “Brick,” rejoins the actor for his latest film and first foray into the sci-fi genre, “Looper.”

Writer: Rian Johnson

What.

The F*ck.

Did I just watch?

I have seen some weird-ass movies in my time, but Looper’s made it to to the top of my current WTF list. What’s so baffling about this uneven, strange, mutation of a movie is that it’s shot in such a way as to almost force you to take it seriously. The actors are big. The cinemtography is top-notch. The production value is impressive. The problem is that this is one of the wonkiest screenplays I’ve ever seen made into a film. We are talking bizarre choice after bizarre choice. But before I even get to the screenplay, I cannot NOT talk about Joseph Gordon-Levitt’s face!

So when I decided I wasn’t going to review this script, I skipped all marketing for the movie. I don’t get to see that many movies where I haven’t already read the script and I wanted to go in fresh. So while many of you had probably been properly prepped for the Mr. Potato Head technology used in this film, I knew nothing about it, and therefore thought the concessions guys had dropped an ounce of acid into my coke.

The first time I saw Gordon-Levitt onscreen I thought, “Man, he’s getting old.” Then, as time went by, I thought, “Or wait, he’s had work done.” And that occupied my thoughts for like 15 minutes – as I kept asking the question, “Why would Joseph Gorden-Levitt have work done on his face?? Is he really that vain?” I was so confused. Until I realized that his lips looked eerily similar to the lips of someone famous. I eventually realized that someone was Bruce Willis, and the purpose of the face-morph-a-thon became clear to me. But then I couldn’t stop thinking about that skit on Conan O’Brien where he’d show you what the baby would look like if two celebrities had a kid. That’s honestly what Joseph Gordon-Levitt/Bruce Willis kept reminding me of!

I’m also dying to know if Gordon-Levitt approved of this ahead of time. Actors are all about their eyes. It looks like Willis’ eyes were glued onto Gordon-Levitt’s face. When you couple that with his glued-on mouth, did Gordon-Levitt do any actual acting?? While I continued to be baffled by that, I eventually realized it was a harbinger of the circus that was to come. But I’ll get to that later.

So what’s Looper about? It’s basically about this guy who lives in 2042(?) named Joe. Joe is a looper. In the future, time travel is illegal but the mob doesn’t care and uses it to dispose of bodies. You see, in the future, it’s impossible to dispose of bodies (even though we – spoiler – see Old Joe’s girlfriend killed in the future. So apparently it can’t be that difficult), so they send these people back to the past, to 2042, where “Loopers” are waiting for them and shoot them as soon as they arrive. That’s Joe’s job, to kill these people and dispose of their bodies. Why they can’t just kill the bodies in the future and THEN send them back so as to keep the job simpler is never explained, but my guess is that it would’ve ruined the plot point needed to create the rest of the story. Not, of course, because it actually makes sense.

Now here’s the thing. This future crime organization doesn’t like the idea of Loopers running around willy-nilly because they very well might tell someone that they (the mob) like to play hide and seek with the past. So 30 years after your Looper contract ends, they capture you and send you back and have your young self kill YOU (your old self). You don’t know you’re killing yourself yet because they send the future people back with bags over their heads. You only realize it afterwards. This is called “closing your loop” and it means you’re retired.

So let me get this straight. This organization isn’t concerned that you might say something in the 30 years leading up to that moment, only once you hit the 30 year mark? Yeah, that makes perfect sense. 30 years later is almost always the moment when people start giving away secrets.

But whatever, I’ll go with it. The movie’s still cool, even if Joseph Gordon-Levitt’s face is freaking me the hell out. I’m no longer scared of clowns. I’m scared of Gordon-Levitt-Willis’s. If they want to make a horror film, cast this man! Cast him now!

Anyway, we’re told about someone from the future called the “Rainmaker.” Apparently he’s closing all the loops because…I don’t know. Because that’s what the script wants. Not because it makes sense. So Old Joe is sent back to be killed by Joe, but Joe botches the execution and Old Joe escapes. There’s this really tough future mob boss who looks like Jeff Daniels who can’t have future people on the run in the past! So he orders his men to kill both Joe and Old Joe.

Up until this point, we still had a movie. I didn’t like all the wonkiness (why do they need these special guns again other than that they look cool??) but it’s a solid setup. It’s a cool idea for a thriller on the run. The old guy can’t just run away. He has to make sure his young self survives too. Because if young self dies, old self dies. That’s cool!

EXCEPT!

EXCEPT somebody decided to introduce TELE-FUCKING-KENISIS into the story. WTF???

Apparently, in the future, there’s telekinesis! Why? I’ll tell you why. Because Johnson needed some reason for the cool shots later on where everything floats. But I’m getting ahead of myself – time jumping if you will, so I need to stay in the present. 10% of the people on the planet can float quarters over their hands. I swear – TEN FULL MINUTES of this movie is dedicated to explaining that people can float quarters over their hands. It’s such a strange weird nonsensical variable that’s thrown into the film that there’s no other way to respond to it than: WTF???

Anyway, that was the weird choice that destroyed the movie. But here’s the story decision that destoryed the movie. Joe holes up in a farm and decides to sit there and wait for his older self to show up so he can kill him and get his life back. The owner of the farm is some woman and her Omen child, who I’ll get to in a sec.

What baffled me is that Johnson completely KILLED the momentum of his story! As I always tell you guys, NEVER put your character in a location for a long time WAITING FOR SOMETHING. Waiting is NEVER INTERESTING. Your character becomes inactive. He’s no longer doing anything. The story slows to a halt. And everything becomes BORING!

Just ask yourself, how exciting is it to watch someone wait for anything. It isn’t! EVER! Now if you have some element of conflict constantly coming at your characters (something attacking them for instance) then you can make it work (even though I still hate the waiting element), but just having someone wait? And wait? And wait?? It’s script suicide! You will bore an audience to pieces.

But what really rolled me, what really had me throwing my hands up in the air, was when The Omen child showed up. All of a sudden, this little kid (who we’re assuming is the “Rainmaker” – which might be cool if I understood who the heck the Rainmaker was and why he was so important) turns out to be this little Omen boy, who gets really angry and when he gets angry….his TELEKINESIS GOES OUT OF CONTROL! And everything in the air floats. And he can rip your body to shreds on a molecular level.

Ummm, WHAT????

When did this become a Steven King novel?! I thought this was about a guy who has to kill his future self! What the hell is going on right now???

Every scene with the kid was comically bad. And nothing about him made sense. He would trip down the stairs and that would trigger one of his super-telekinesis freak outs, which would result in people exploding! By falling down the stairs!! It was just so bizarre. And what did any of this telekensis stuff have to do with the Looper stuff! The Rainmaker of the future was “closing loops.” Why? And why did he have to have special telekinesis powers to ask Loopers to close loops? Didn’t he just need the power of asking?

I could go on about how bad this was but what would be the point? What this script needed was someone to tell Johnson to ditch the whole Rainmaker, Omen, Farm plot and focus on the intricate world of looping and the unique setup of two people on the run, one of whom can’t survive unless the other survives. Someone please close my loop. Then blow me up on a molecular level.

What I learned: Never hole your characters up in a location and have them wait for something for too long UNLESS they’re constantly battling lots of outside conflict. Main characters waiting for shit to happen is the worst thing you can do to a story.

Genre: Horror

Premise: A young woman takes two friends back to the house her mother murdered her family in to recover her things before the house is torn down. Once inside, however, the house refuses to let them leave.

About: The Quiet Ones is the first picture of a new financing partnership between Shine America and Emjag Productions. The partnership is looking for projects that can be released on “multiple platforms” which I’m guessing means the big screen and the internet? Writer Vikram Weet has another project he sold to a Russian production company called The Dyatlov Pass that’s being directed by 80s action director icon Rene Harlin!

Writer: Vikram Weet

Details: 86 pages (undated)

You say I don’t review enough horror? Well today is why! Okay okay, that’s not very nice. The Quiet Ones is an adequately written screenplay. But it makes no attempt to be unique in any manner after the setup, and falls into some of the biggest cliche horror pitfalls out there, the biggest of which is having things happen for no reason other than the writer wants them to happen. Take the opening page, for example. We’re told the script is going to take place in one continuous shot.

I guess that sounds kinda cool. Until you realize that there’s no point to it. It’s just a gimmick. Absolutely nothing would change if the story was cut normally. And if something’s not necessary, then why include it? Unless the characters are being videotaped by a physical camera in one continuous shot for some reason. Which MAY be the case, but the ending is so confusing that it’s impossible to tell.

The Quite Ones, unfortunately, disappoints in many areas, the biggest of which are the cliche scares. This is one I simply can’t let pass. Even if you’ve never taken a screenplay class in your life, one just knows – don’t repeat cheap scares that have been in every horror movie and video game known to man. Here we have the dolls and stuffed animals…WITH THEIR EYES CUT OUT! Someone is dead, but when our hero steps over them, their hand LAUNCHES UP, GRABBING THEM. They’re still alive! We also have the creepy pale dead kid who keeps popping up under stairways and in mirrors.

Which is strange, because the setup itself is actually kind of original. I’ve never seen a horror story start with three kids breaking into a house where the protagonist’s family was murdered. I liked the immediate goals that were set up, which seemed logical. They wanted to get everything valuable they could before the house was torn down tomorrow (ticking time bomb! also good!). So when this thing started, I was quite optimistic. But then the familiarity started creeping in, and once it got its clutches on the script, it never let go.

The Quiet Ones introudces us to Madison, a stunning brunette in her mid-twenties who shows up at a house in the middle of nowhere with her boyfriend, slightly older Jake, and her cousin, attitude-laced Isaac. Turns out Madison didn’t think through her accomplices very thoroughly because Jake and Isaac hate each other. We’re not talking frenemies here. The two genuinely hate each other. But Isaac has some breaking and entering experience that’s needed to get into the house, so Jake rolls with it.

Soon we find out this is the house where Madison grew up. There aren’t many good memories here though. Turns out Madison’s mom went nutso and killed everyone. The term “everyone” isn’t ever completely defined here, since we keep learning about more family members as the story evolves, but at last count I think it meant her father, her brother, and her sister. Madison was the only one who made it out alive.

And since the house is getting plowed over after 20 years of abandonment, Madison offered to give Jake and Isaac anything they found in the house before Bulldozer Time. Which would be a cool plan if strange things didn’t start happening. Like pale little four year old boys playing hide and seek in the shadows. And sinister looking dogs blocking our temporary criminals from making it back to their car. And stuffed animals with their eyes cut out.

At some point, it’s hypothesized that the house wants them to stay here for some reason – probably to kill each other. Apparently, this is exactly what happened to the mom, who was told by the house to kill the rest of the family. Now it’s finishing the job, by having Madison kill her boyfriend and cousin. Our trio is freaked out of course and wonders how they’re going to escape. But can’t they just wait for the wrecking crew to show up in the morning? The ones who are going to tear the house down?

Avert your eyes for this ending spoiler since it’s the final twist. But since it makes no sense, I don’t think I’m spoiling anything. At the end, when Madison looks in the mirror, she sees her mother, who apparently has been the “POV” of the camera the entire time. Ummm, what? There was a camera? Or is she a ghost? I’m not even clear on if she’s still alive in a mental institution somewhere or dead. But apparently, she’s been taping these guys the whole time? Or watching them? But then if she’s the POV, why does she become Madison’s POV when she looks in the mirror? Are Madison and the mom the same person? Did these two come here with Madison’s mom and not realize it?? What the hell is going on right now????

Lazy twist endings are one of my biggest pet peeves. Throwing a twist onto the end of a story just to have a twist, regardless of whether it makes sense or not, is one of the laziest and schlockiest things you can do. If you are going to go with a twist ending, at least make sure that it has some semblance of a connection to the rest of the material, that it’s paying off some sort of setup. I don’t even know what the POV of the camera was supposed to be here. A person? A video camera? A ghost? And I’m not sure it would’ve made it any better if I did know.

Anyway, that totally killed Quiet Ones for me. And look, okay, I’m not disillusioned. I understand that horror movies are made for the 12-18 crowd. I know those people don’t sit there and analyze the intricacies of screenplay structure when they watch a film. I know they just want to squirm in their seats and have an excuse to put a hand on a member of the opposite sex for a couple of hours. But I don’t believe that’s a license to be lazy. I still think you owe it to yourself to write the best story possible, because the better the writing, the further you expand your demographic. There’s an entire group of people out there who, like me, are dying for smart horror!

And until I start reading more horror scripts like Hidden, a script I reviewed a couple months ago, where there was some actual thought put into the story and where some original choices were made, I’m going to keep answering the “Why don’t you review more horror?” question the same way. “Write me a good horror screenplay and I will review it.”

I’m not going to say that The Quiet Ones was awful. The writing itself was fine. There were even a handful of freaky moments, such as the dogs. The movie will also be easy to market and probably make some money. But the combination of the cliche scares and nonsensical ending destroyed any enjoyment I gathered from the read. Which is why I can’t recommend The Quite Ones.

What I learned: Writing yourself into corners can be fun. It forces you to come up with clever ways out. I know the Coens do this a lot. But be careful about writing your entire story into a corner. If you’re making all this funky crazy stuff happen and you don’t have a specific idea of how you’re going to explain it all, you might find yourself stuck in that corner for good. I would suggest knowing your twist or surprise ending ahead of time, and then back-engineering the story so that the twist comes together naturally.

Genre: Drama

Premise: Two lovers/serial killers drive cross-country to Los Angeles in 1974, where they plan to kill Elvis Presley.

About: Scriptshadow favorites Eddie O’Keefe and Chris Hutton are back, with their third script reviewed on the site. The first was the highly ranked Black List script, When The Streetlights Go On. The second was the wild and eerie The Final Broadcast. And today it’s Shangri-La Suite. I may be mistaken about this, but I don’t believe this script is purchased yet.

Writers: Eddie O’Keefe and Chris Hutton

Details: 105 pages. Draft 8, May 3, 2012

Today was supposed to be that rare day where I actually reviewed a romantic comedy. Not only that, but it was actually a pretty good romantic comedy! Starring the Reester (Reese Witherspoon). That’s why I realized it was good. Since Reese Witherspoon is the only actress left who can open a romantic comedy, it means all the best rom-com material is competing for her. So if she’s attached to something, it’s usually pretty good. But alas, the powers that be got in the way and disallowed a review, so all I can say about The Beard (the script) is that I enjoyed it.

So where does that leave us? In a much better place as far as I’m concerned! Cause it means I get to review another script by a couple of my favorite writers, Eddie O’Keefe and Chris Hutton. When The Streetlights Go On made me a fan. The Final Broadcast made me the president of the fan club. So what did Shangri-La do?

I’ll get to that in a second, but before I do, let’s address Eddie and Chris’ critics. As much as their work is loved around town – and they’ve literally met everyone in Hollywood based on their two scripts – everyone’s concerned that Broadcast and Streetlights AREN’T MOVIES. They’re great scripts with original voices. But they don’t fit into any genre. They don’t have any big movie moments you can put in a trailer. Producers are afraid to put money behind them because they’re not easy sells. Which I think is dumb of course. No, they’re not Transformers. But with the right director, both movies could tear up the independent market.

Anyway, the reason I bring it up is because Shangri-La is the most “movie-ish” script they’ve written so far. It’s got a goal (kill Elvis), it’s got a love story, it’s got blood, shootouts, murder. The narrative is much more conventional. And it’s got Elvis! If ever one of their scripts was going to be turned into a movie, this would be it. Which begs the question: Should it be turned into a film?

It’s 1974 and 18 year old redhead Karen Bird has had every opportunity in life to become anything she wants. She was born into a rich family, went to nice schools, is pretty and likable. But Karen had a tough time with the whole religion thing and eventually started wondering what the hell the point of life was. The sun was going to burn out at some point so why bother? This led to drugs which led to screwing a lot of guys (in a cemetery of all places) which led to her parents losing faith in her and sending her to a mental hospital to get better.

25 year old half-Chippewa Jack Blueblood had quite a different life. His mother died during childbirth. His father hated him for it. Which meant a lot of drinking and a lot of beatings. As a result, Jack acted out, doing a lot of drugs and getting in trouble with the authorities. This led to the state sending Jack to the mental hospital to get better.

This is where Jack and Karen met and fell in love. It’s where Jack told Karen his destiny – He believes he needs to kill Elvis. Which doesn’t make a whole lot of sense because Jack loves Elvis more than anything. It’s Elvis’ music that helped him through all the hard times, all the beatings and the run-ins with the cops. But Jack is convinced that when he listens to his favorite Elvis song backwards, his dead mother is telling him to kill him.

At first it’s just a fantasy, but when one of the doctors rapes Karen, Jack goes apeshit and kills him. Now they have no choice but to leave, and once that happens, they need a destination. It turns out Elvis is playing a concert in Los Angeles on May 11th. That becomes D-Day, the day Jack plans to fullfill his destiny.

The two aren’t mindless killers like you’ve seen in some of these movies. They kill because they’re forced to or because the people in the way are really really bad. They eventually pick up one of Jack’s old friends, Teijo, who’s convinced he was meant to be a girl and that he can fulfill that dream in Los Angeles. But with the cops in hot pursuit of them and with Karen starting to have doubts, it’s unclear whether they’ll even make it to LA, where a beat-down end-of-his-career Elvis is waiting. However if they do, you can guarantee it’s going to be one hell of a finale.

Like I said at the outset, this is the most traditional script Eddie and Chris have written. But their unique voice, their talent, and their distinct flourishes are still all over it. Right away, for example, we’re introduced to Jack, whose mother died giving birth and whose father is a Chippewa Indian. I mean, who thinks of that?? The average writer will make a protag’s parents two white garden-variety folks and think nothing of it – not realizing that who your parents are shapes everything about you. A white mother who died giving birth to you and a deadbeat abusive Native American father is such a unique choice that Jack immediately feels unlike any character you’ve ever seen. That’s why I love these guys. They don’t do it like everyone else does it.

We also have a narrator for the story, which is usually a big no-no, but these guys manage to weave him into the atmosphere of the piece, making sure he doesn’t feel like your typical exposition-vessel, but rather a necessary component of the quirky story. These guys love voice overs, and they do it about as well and as naturally as anyone in the business.

Their dialogue also continues to be top-notch. I don’t know what Eddie and Chris drink before writing their scenes. All I know is I want some. Here’s a line of dialogue from a broken-down Elvis in the middle of the script: “When I was young, Colonel, I felt things. I had long hair. Thick, long hair and good looks. Life just tasted better. Hurt harder. All neon. Now life is just a series of airplanes, limousines, and freaks carryin’ luggage up to hotel rooms you ain’t never been before. Tellin’ lies.” I mean how do you write dialogue for one of the most popular pop culture figures in history?? And yet these two do it with ease. I would kill to be able to write something half as good.

On the flip side, the critics of Shangri-La say that the script is too derivative of Bonnie and Clyde and Natural Born Killers. I guess that’s the danger of writing something commercial. The more commercial you get, the more likely that movie’s already been done before. I’ve only watched Bonnie and Clyde and Natural Born Killers once, and both were forever ago, so those viewings didn’t affect my opinion. However I can understand why it might’ve affected others.

For me, it’s more about comparing Shangri-La with Eddie and Chris’ other work. What I loved so much about those scripts was that I never knew what was coming next. I talk about that all the time here. It’s rare when I genuinely don’t know where the story’s going. So I love it when a writer’s able to keep me guessing. Streetlights especially, having that passive uninvolved narrator become the main character for the final act was genius in my book.

With Shangri-La, I knew where the story was going. I didn’t necessarily know how it was going to end, but I knew where we were headed. And I guess, again, that’s a byproduct of writing something more traditional. To be honest, I can’t even call that a fault. Movies with goals and clear directives are what I’m trying to teach readers of Scriptshadow to write. I think Eddie and Chris are simply victims of their own voice here. They’d established a style where you never knew what was coming next, so it was a heavy shift to read something more traditional.

Having said that, I still enjoyed the heck out of Shangri-La. All the characters were unique and interesting, as is to be expected. I loved how they tackled Elvis as a character. I loved the love story. And even though I knew where the script was heading, I did not expect it to end like it did. So that was cool. Once again, I think these two have proven why they’re two of the best writers in Hollywood. Now it’s a matter of waiting for Hollywood to realize that.

What I learned: Remember, you have the power to make ANYONE in your script likable, even serial killers. All you have to do is create a sympathetic reason for why the characters are doing what they’re doing. The reason we still like killers Jack and Karen is because each one of their kills make sense. Jack kills one of the doctors at the hospital, but only because he raped Karen. Jack kills his father, but we establish earlier that his father used to beat the shit out of him when he was a kid. They kill some cops, but these are cops who were trying to kill them first. If you DON’T create reasons for your protags to do bad things, there’s a good chance we won’t like them and hence, won’t want to follow them.

What I learned 2: Know your characters’ parents. What kind of people were they? What kind of people were they to your hero? We are who we are, mainly, because of our families. So make sure you know your hero’s parents and how they raised/treated your protagonist. Were they supportive, cruel, abusive, absent? The answers to these questions will give you a wealth of information you can use to shape your character.