Wanted to give a shout out and congratulations to longtime Scriptshadow reader Emily Blake over at Bamboo Killers. You may remember that Emily’s logline for her script “Nice Girls Don’t Kill,” finished Top 5 in our First Ten Pages contest a few weeks ago. She ended up as one of the finalists at the TrackingB contest with another script, “How My Wedding Dress Got This Dirty,” and quickly secured a manager and an agent at ICM. She’s now working on rewriting “Nice Girls Don’t Kill,” incorporating some of the notes you gave her on the First Ten Pages. That’s 1 down and 49 to go for Scriptshadow readers who are going to break in this year. It’s possible people. Just keep working hard!

To submit your script for an Amateur Review, send it in PDF form, along with your title, genre, logline, and why I should read your script to Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Keep in mind your script will be posted in the review (feel free to keep your identity and script title private by providing an alias and fake title). Also, it’s a good idea to resubmit every couple of weeks so that your submission stays near the top of the pile.

Genre: Action/Adventure

Premise: (original 6th place logline) A wild young woman gets seduced into a high tech, storm chasing motorcycle gang that loots and murders under the chaotic veil created by natural disasters.

About: For those of you with bad short-term memory, The Wreckage was unfortunate enough to finish one spot out of the top five of the First Ten Pages contest a few weeks back, just missing a review. Well what a sweet consolation prize. Today, we’re reviewing the entire script!

Writer: Michael McCartney (story by Laton and Michael McCartney)

Details: 102 pages (This is an early draft of the script. The situations, characters, and plot may change significantly by the time the film is released. This is not a definitive statement about the project, but rather an analysis of this unique draft as it pertains to the craft of screenwriting).

When Michael McCartney, the writer of today’s script, was pitching his premise some months back, producers told him that no one was interested in purchasing a storm flick. Not too long afterwards, Hollywood purchased two big storm projects, one a heist film similar in vein to The Wreckage. Just goes to show that nobody likes anything until they like it. But I can assure you The Wreckage is nothing like those scripts. McCartney, the eldest grandson of Beatles legend Paul McCartney, does something quite different here. The question is, did he go too far with it?

I was just joking about the Paul McCartney thing by the way. Michael’s not really McCartney’s grandson. Anyway, the wily 24 year old twister known as Maddy is sick of living a lame life in Wichita Falls, Texas. She’s way too unchained for this place. I always tell you guys to introduce your characters with an action that tells us who they are. Well, Maddy’s introduced having sex with her boyfriend while he’s driving. Yup, I think we know who this character is right away.

Afterwards, Maddy heads back to her parents’ jewelry store on the eve of an approaching storm. Things look so bad, in fact, that they have to board up the windows. But apparently it’s not one of those “you only have to board up the windows and you’ll be okay” type storms. This is the type of storm that rips buildings down.

And that’s exactly what happens. While Maddy survives the destruction, her father dies and her mother is injured. As Maddy tries to figure out what to do, a crazy ass motorcycle gang pulls up, led by a creepy sonofabitch named Scarecrow. Scarecrow and his gang wait for storms to hit towns then ride in, when no police are around, and start looting. Once Scarecrow sees Maddy though, he realizes he’s found the loot of the century.

Scarecrow and crew grab Maddy and drive off into the sunrise, Easy Rider style, and at some point poor Maddy realizes she’s been kidnapped. Cut to FBI Agent Leo, whose since-deceased sister used to be friends with Maddy in high school. He’s tasked with finding and saving Maddy.

Problem is, Maddy starts to like it with this group of vagabonds. They’re as bonkers as she is. Shit, even moreso! They rob places to survive. And that’s probably the life she was heading for anyway. So she figures, “What the hell Charles Manson wannabe. I’ll join your cult!”

The rest of the script follows the motorcycle gang around as they beeline into tornadoes and rob everything in sight. Scarecrow preaches a life of freedom, of not having to live by society’s rules. Of course, the impressionable Maddy loves this at first, but eventually realizes she isn’t free at all. She’s Scarecrow’s puppet, just like everybody else in this gang. And she wants out. I think it might be too late for that though, Maddy. This is The Family. Once you’re in, you’re in for life.

The Wreckage is kind of like a wild college night. You know what I’m talking about. Those nights that are filled with both the best and the worst of you? I have to give credit to McCartney. He’s not making any obvious choices here. But I think his story’s too unhinged.

I mean we have a sort of heist/robbing/looting film, a motorcycle/Easy Rider/travel film, a storm film, a cult film, a kidnapping film. I felt like ideas were competing against each other left and right, and I’m not sure that the best of those ideas was featured. In The Wreckage, the motorcycle gang theme actually takes precedence over the much cooler idea of robbing places during storms.

The robbing, in fact, felt secondary, something the group did to pass the time. Since I never got the sense that they were hard up for money, I wasn’t convinced any of the robbing was even needed. And if you’re writing a movie about a crew going into storms to steal things and the crew doesn’t have a strong purpose/reason to do so, I’m not sure you have a movie. There needs to be stakes attached to each robbery, or else they feel meaningless. In Fast Five, Paul Walker needs to steal all that money so he and his fiance can go off the grid for good and never worry about money again (or at least until Fast Six). Now there’s purpose to the heist.

Something else that worried me was Maddy liking the group. She actually began enjoying herself. So when we cut to the FBI chasing after her, we’re not really interested in whether they save her or not – because Maddy doesn’t want to be saved. If would be like if that chick in the basement in Silence Of The Lambs became BFFs with Buffalo Bill and they were chilling on the couch and smoking pot all day. Would we still be interested in Jodie Foster saving her?

But the biggest thing that needs fixing in this script, by far, is the FBI agents. These two have to be two of the most inadequate FBI agents in history. They’re never anywhere CLOSE to catching Maddy. And they spend half the time sitting in rooms talking about shit. These are your agents! They need to be out there DOING SHIT. They need to be ACTIVE. I don’t remember a single scene in The Silence Of The Lambs where Jodie Foster was sitting down.

I think Michael also needs to be aware of going *too* on-the-nose in places. At one point his partner says to Leo, “You know they’re different people, don’t you? Your sister and the Dylan girl.” This is followed not too long afterwards by Leo, drunk, staring at a picture of his dead sister. Talk about hitting us on the head. Yes, we know: he’s really trying to save his sister. I dig that Michael made a personal connection between Leo and Maddy, but all you needed to sell this was the picture scene, particularly because it’s *showing* us and not *telling* us.

I will say this. There’s a beautiful, almost poetic, quality to these deranged cyclists barreling into monster storms. You also have a diabolical villain in Scarecrow, who I thought was well-crafted. But the engine driving this Harley needs a major overhaul.

I think it starts with the premise. We need to streamline the direction so there aren’t so many competing elements. If we’re not going to properly utilize the “storm-heist” angle, I think it should be a kidnapper flick. After the storm, Maddy sees the bikers kill someone. They spot her, snatch her up, and bring her with them because she’s a witness. They plan to kill her, but for a number of lucky reasons, she stays alive. Now you have a girl in peril, which gives the FBI pursuers (assuming they actually pursue in this next draft) a lot more weight. She’s also no longer chumming it up with everybody – which provides the script with more conflict. I think that would work better.

If this is a “storm-heist” movie, however, I say you drop Maddy. Just focus on the gang and the FBI pursuing them.

The Wreckage was an interesting read. But the plot needs some streamline soup before I give it a “worth the read.” Still, I wish Michael the best with it. Tell your grandpa I love his music!

Script link: The Wreckage

[ ] Wait for the rewrite.

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Beware the movie concept that contains competing ideas, as those ideas will be fighting for attention the entire way through, leading to an uneven story. You can’t make a prison break movie, for example, that’s also about a boat race. Know when an idea requires its own movie. That’s what threw me here. Going into dangerous storms to rob towns is the star concept, but it takes a back seat to the cult-motorcycle-kidnapping storyline.

I know you guys are busy. You’re getting back into work, you got families to tend to, you have scripts to finish. Who’s got time to come up with a list of resolutions? I mean, we never end up following them for more than a week anyway. What’s the point? I’ll tell you what the point is. The point is making yourself a better person dammit! Which is why I’m going to write your New Year’s resolutions for you. Well, not your personal resolutions, but your screenwriting resolutions. You see, I want this to be an amazing year for all Scriptshadow readers. I’m predicting a good 50 of you will break through and find agents/managers this year, and ten of you will go on to sell a screenplay (maybe even more!). But it’s not going to be easy. You’re going to have to work your butt off and make the right decisions along the way. Which is what I’m going to help you with. Here, my friends, are your 2012 screenwriting New Year’s resolutions!

1) Believe in yourself. – Guys, you cannot succeed unless you believe you can. A lack of confidence affects every aspect of your screenwriting. You won’t write as much. You won’t write as well. You won’t try as hard to get your material out there. You’ll project an image of negativity. You have to believe that big things are going to happen if you really want to make it. I just read this article over at CNN which said that while most people give up on their small resolutions, they stick with their big ones, because the big ones require more commitment. So commit to a big spec sale and BELIEVE you can do it. That one shift in attitude is going to change your life.

2) Write marketable concepts – Guys, I mean, come on. Enough. Stop with these scripts that have no chance of doing anything. Trying to be that 1 in a trillion screenwriter who breaks through on a “nothing” premise is a suicide mission. The number 1 reason a script doesn’t sell is because the concept is weak/non-existent. You want to write your “change the world” script? Break in first. Look at I Think My Facebook Friend Is Dead. Clint and Donnie will be the first ones to tell you they have a lot left to learn, but they came up with a great premise and now their test movie is arguably the frontrunner for the million dollar Amazon prize. Don’t take yourself out of the game this year before you’ve even started to write. Be smart and choose a concept that has a chance of selling.

3) Take chances in your writing – No, not on a boring premise, but on your actual story. This is one I’ve been thinking about a lot lately. We get so wrapped up in the rules (I’m no exception to this) that we forget we’re still dealing with art here. And every famous painting or movie or song or play has that certain “je ne sais quoi,” – something in it you can’t quite explain. And that unexplainable quality comes from taking chances. If everything’s exactly by the numbers then that’s how your story will feel – exactly by the numbers. Just make sure you’re not taking chances ONLY to take chances. It still has to feel right and appropriate for your story.

4) Don’t focus on anything negative – This is a sister resolution to #1, but you guys gotta stop focusing on all the negative information out there about making it as a screenwriter. Are you TRYING to talk yourself out of success? Do you WANT to convince yourself that it’s impossible? Because the information is out there if you want it: “Only one in a million screenwriters actually makes it.” “It’s impossible to become a screenwriter if you don’t live in Los Angeles.” “New screenwriters never sell spec scripts.” Don’t expect anything good to come out of you obsessing over these facts that have been so exaggerated over the years that they’re not even accurate anymore. Just focus on what you can control: Writing and learning. The more writing you do and the more learning you do, the closer you’ll get to breaking in. This business is not as dependent on luck as you think. The people who work their asses off and are serious about their craft almost always find a way in.

5) Think outside the box – This is a creative industry. That’s what we do. Create. So use some of that creativity to find a back door into the business. People have been doing this forever, and even though showmanship isn’t as beloved as it used to be (screenwriters sending ticking clocks to producers in anticipation of their spec, “The Ticking Man,” which went on to sell for a million bucks), there are still a lot of backdoor creative opportunities to get in. By starting this blog, I increased my rolodex by 200 fold, giving me way more opportunities than I ever dreamed of having. What will you create? What sneaky little thing do you have up your sleeve to break into the industry?

6) Do not deviate from the plan – There are a lot of great screenplays out there that we’ll never see because they never get finished. Why? Because you never finish them. Because you get bored. Because you don’t want to do the hard work. Because it’s SO MUCH EASIER to start on that new exciting idea you came up with yesterday. I got news for you buster. Screenwriting is hard. It takes dedication. It takes work. It takes you barreling through those shitty moments where you don’t have any idea what to do with your story. Instead of moving on to something new that will eventually put you in the same position you’re in now, stick with it. Finish your screenplay. That sense of accomplishment will give you confidence to rewrite it until it’s perfect. I know it isn’t easy guys. But nothing worth having in this world is.

7) Be brave – Being passive in real life isn’t much different from being a passive character in a screenplay. It leads to a story that goes NOWHERE. You’re going to have to buck up and do some things you don’t like doing if you want to advance your career. No, I’m not talking about streetwalking on Hollywood and Vine. But you’re going to have to call agents, call managers, send more e-mail queries, follow-up more e-mails. You’re going to have to call that long lost sorta-friend who knows that production manager even though it’s going to be an awkward conversation. Any way you can get people to read your scripts, do it. Because you never know where that break is going to come from. It’s usually from a guy who knows a guy who knows a guy who gave your script to them. That person calls you in. You end up hitting it off. He hires you for a rewrite. And what do you know? Your career has begun. Breaks materialize in the oddest of places. But they never materialize for people who keep their scripts hidden on their hard drives. Be brave people. Get your shit out there.

8) Work more on your characters – I mentioned this in my interview a couple of weeks back. The biggest difference I see between amateur screenplays and professional screenplays is character development. So if you’re serious about this screenwriting thing? It’s time to put a lot more effort into character. Read everything you can about it. Learn how to arc a character. Learn how to build compelling relationships between characters. Start writing 10 page character bios for your main characters. Go through my Scriptshadow Character Generator again. It doesn’t matter how cool your plot is. If you don’t have characters we care about, your script will be LAME.

9) Get honest feedback – We writers like to live in a dream world, a bubble that allows us to live on in perfect bliss. In this bubble, we improve at a glacial pace, because nobody ever tells us what’s REALLY wrong with our writing. When we do give our script out, it’s to friends or family, the people we know will support us and pat us on the back. I’m sorry but I’m popping your fucking bubble. Bubble time is over loser. This year, I want you to make a commitment to get some honest feedback. Whether it’s joining a writers group, forcing friends to stop bullshitting you, or paying for professional notes. You need someone telling you the truth. Just remember, the main reason writers avoid this is because they’re afraid of being told their writing is bad. Don’t think of it that way! Your writing IS bad. 90% of all writing is bad. But in order to knock that percentage down, you need people telling you what you’re doing wrong so you can IMPROVE.

10) Help others – This may seem like a touchy feely filler resolution, but it’s probably the most important resolution on this list. All the writers I meet are so focused on THEMSELVES, on their scripts and their problems and their endless screenwriting heartbreaks, that they’ve lost sight of the bigger picture. Here’s the truth. The more you help other people, the more people will want to help you. I PROMISE you this. I SWEAR to you this will happen. Just try it for a month. Start asking people what you can do for them. Offer someone help in your specific trade. Read other writers’ scripts and give them notes. It will come back to you in ways you’d never imagine. And best of all, you’ll feel good about yourself.

Let the damn New Year begin!

Genre: Romantic Comedy

Premise: (from Black List) A political journalist courts his old babysitter, who is now the United States Secretary of State.

About: Dan Sterling has developed his comedic chops writing for TV since the mid-90s. He’s worked on The Sarah Silverman Show, The Jon Stewart Show, King of The Hill, and South Park. He was actually the first writer other than Matt and Trey on South Park. Flarsky finished 21st on 2011’s Black List with 17 votes.

Writer: Dan Sterling

Details: 118 pages – undated (This is an early draft of the script. The situations, characters, and plot may change significantly by the time the film is released. This is not a definitive statement about the project, but rather an analysis of this unique draft as it pertains to the craft of screenwriting).

It appears that there aren’t many fun scripts on this year’s Black List. I wanted to include something light for this week’s reading and started scrolling down the list only to realize that almost every script sounded incredibly depressing. Is this the Black List or the “Wear Black List?” As in we’re going to a funeral! (sorry – I’m trying out some new material in 2012). Then I came across Flarsky. Finally, a comedy!

But………it was a politically charged romantic comedy. Uh oh. I’d probably have more fun reading through a stack of TPS reports. I HATE political romantic comedies. The comedy’s always buried under some stupid political message. I worked behind the Los Angeles Federal Building for 7 years, where they had a demonstration every weekend. I’m done with political agendas.

But it did score high on the Black List so I figured it had a *chance* of being funny (“So you’re saying there’s a chance!”). I poofed up my pillow beforehand though. That’s the one good thing about bad scripts. They’re perfect nap initiators.

But that nap never came. Because I loooooooved me some Flarsky!

Charlotte Field is the gorgeous 30-something Secretary Of State and the United States’ closest thing to royalty. This woman makes Jackie Onassis look like Snooki. She’s funny, smart, powerful, cool, and everybody’s frontrunner for the 2016 Presidential race.

Fred Flarsky is the opposite. He’s dull, weak, uncool, unkempt, and everybody’s frontrunner for 2012’s most annoying drunk at the end of Larry’s Bar. But it wasn’t always like this for Flarsky. He once held promise. He once was a great writer.

Well, he still is a great writer. Unfortunately, that writing is happening at some 4th rate newspaper nobody reads. Until the inevitable happens. Yes, due to that bastard known as the internet, which is destroying print newspapers left and right, poor Flarsky is fired, leaving him in an even more pathetic state than he was already in, if that’s possible.

Strangely enough, Flarsky once had a connection with Charlotte Field. She used to babysit him when he was a kid, and in one of the most monumental moments of his life, he worked up the courage to plant a kiss on her, to which he still thinks about this day. But that was 25 years ago. Since then, their lives have gone in completely different directions.

But Flarsky’s best friend, Lance, has a different assessment. Lance believes that you can have anything you want in life if you try, and encourages Flarsky to go after Charlotte. In fact, he has two tickets to a benefit she’ll be at tonight! Flarsky agrees reluctantly, and is shocked when Charlotte recognizes him, inspiring an impromptu jaunt down memory lane.

When Charlotte finds out Flarsky is a writer, she hires him to help her with her speeches. The next thing you know, Flarsky’s gone from the seat at the end of the bar to the seat at the front of the plane. Despite Flarsky being nowhere near Charlotte’s league, she finds something charming in him, which leads to – gasp – a relationship! Since Charlotte’s married (a marriage that’s been technically dead for years), her advisors try anything in their power to get rid of Flarsky, as even the hint of this affair threatens each and every one of their jobs. In the end, Charlotte will have to make a choice between her political ambitions and the man she’s fallen in love with, Flarsky.

I thought this was hilarious. As you all know, I love underdog stories, and there’s no bigger underdog than Flarsky! I suspect women are going to hate this script because it’s yet another example of a loser guy getting the impossibly beautiful girl, which kinda never happens in life. And I might have thought that myself if not for the babysitting connection. The fact that they knew each other beforehand gave the relationship just enough credibility to make it believable. Now does Flarsky have to be the single biggest loser on the planet (a drunk, unkempt, bad hygiene, depressed, unconfident)? Maybe Sterling went a little too far in that department, but the writing was so strong that I went with it.

What I was really happy about was that the political stuff never got in the way of the story or the comedy. I see this happen sometimes, especially in these political scripts, where the writer believes we care more about some issue our characters are promoting rather than the characters themselves. This is a romantic comedy. That means the characters and the relationship have to come first. And Sterling wisely focuses on exactly that.

My only problem with the script was the first act. The setup for this kind of situation is always tough because getting two people together who are this far apart in stature requires its share of forced moments. For example, it seems like the only reason Flarsky’s best friend Lance is so rich is so Sterling had a believable way to get Flarsky into the high class benefit Charlotte was attending. Then there’s something about Flarsky getting a broken leg and Charlotte feeling responsible so she takes him to dinner. I don’t know. I could definitely feel the writer tapping the keys on that one. It’s never easy to navigate these choppy plot mechanic waters though and I suppose Sterling did a manageable job of keeping it sort of believable.

The thing that really killed me though was the forced “save the cat” moment. I HAAAAATE forced save the cat moments! These are moments where the writer tries WAY too hard to make you love his character. Here, a bunch of meatheads are talking about how much they hate blacks and gays. Flarsky overhears this and tries to beat them up. Uhhh, why don’t you just put Flarsky in a time machine and have him murder Hitler.

But once we get past that first act and into the romance, the script really begins to fly. In these screenplays, it’s all about the chemistry between the leads, and Flarsky and Charlotte are perfect together. I so wanted them to stay together in fact, that I mouthed “noooo” when Charlotte’s sworn enemy (a Rupert Murdoch like media mogul) got hold of a sensitive picture of her that threatened to blow the whole affair up.

There’s also something fresh about the setting that we haven’t seen in a romantic comedy before. I mean in what other rom-com have you seen the leads having to dodge rockets? And all the jetsetting (as they go from country to country) keeps the script moving at a breakneck pace, which is also rare for the genre.

And overall, I just loved the predicament. Charlotte can’t go public with this affair. If she does, she ruins her marriage, loses the trust of her followers, and loses her shot at becoming president. Not to mention her entire team is out of a job. So the stakes are very high. When Flarsky first comes to terms with that realization – the fact that their relationship can never be real, it’s a genuinely sad moment. And I, for one, was wondering how it was going to end. In a romantic comedy no less. When you ALWAYS know how it’s going to end.

The success of this film will depend on the casting, as it always does with romantic comedies. But assuming they get that right, this movie should do well, because the script is there.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: The impossible choice. Force one of your leads into an impossible choice at the end of the movie. Here, Charlotte must choose between her career and Flarsky. If you set that decision up well (where each choice has devastating consequences), we’ll be dying to know what they choose.

Genre: Drama/Thriller

Premise: When they find out he’s robbing graves, including their father’s, a brother and sister living in a small town decide to blackmail the local undertaker. But they soon find themselves in way over their head.

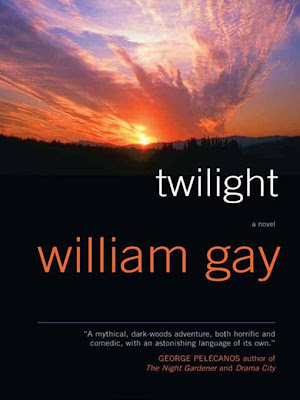

About: Chad Feehan, the writer of Beyond The Pale, produced the film “All The Boys Love Mandy Lane,” and wrote/directed “Beneath The Dark,” which came out in 2010. Beyond The Pale is actually an adaptation of the book, “Twilight,” by William Gay. Beyond The Pale finished 10th on 2011’s Black List with 27 votes.

Writer: Chad Feehan

Details: 109 pages – March 2, 2011 draft (This is an early draft of the script. The situations, characters, and plot may change significantly by the time the film is released. This is not a definitive statement about the project, but rather an analysis of this unique draft as it pertains to the craft of screenwriting).

I heard mixed things about this one and had been avoiding it mainly because of the title, which had me imagining a man wandering around the desert, carrying a pail. No, I’m serious. I imagined a Western where a mysterious man strolls into town with nothing but a pail. The big mystery would be, what’s in that pail? Rainwaiter possibly? Toiletries? I didn’t know. But whatever it was, I didn’t want to read it anytime soon. Then again, I thought if this script made the Black List with that title, it may be the best script ever written.

It turned out Beyond The Pale wasn’t a Western at all, but another small-town murder tale, which is like catnip to the Black List. We get 5 of these a year on the list at least, some of them good, some not so good. Where Beyond The Pale ranks is debatable. This is such a strange screenplay. It’s almost like two different movies, the first a small town blackmail tale and the second a chase film. If you can roll with that shift, you’ll like it. If not, prepare to be disappointed.

It’s 1973 and we start with a family getting killed, only to then jump back to, you guessed it, 13 days earlier! Yes, we have yet another screenplay that begins with a flashforward. I think you guys are finally getting an idea of how often I see this device. Multiply every time I highlight it in a review by five and you’re getting close. It wouldn’t be so bad if EVERYBODY didn’t use it. But because they do, it starts your script off on a cliché note. Never good.

Anyway, the flashforward introduces us to Granville Sutter, a local murderer who has somehow evaded every murder he’s been accused of so is now living freely in this town, eager to target his next victim. He’ll get that chance soon enough.

13 days earlier we meet Corrie and Kenneth Tyler, a barely out of high school brother-sister duo. Corrie has really come into her own, and has all the men in town drooling over her every step, which has forced Kenneth into a protector role, something he’s had to get good at due to their family’s lousy reputation.

And then of course, it’s not going well for Corrie. She’s 72 hours away from losing her place and needs money fast. It just so turns out that the siblings lost their father recently, and discover that the local undertaker, Fenton Breece, has been grave robbing everybody he buries, including their pa!

But it gets worse. When they raid his office, they find pictures of Breece engaged in sexual acts with dead female bodies. Uh-oh. Spagettio. Necrophiliaism! Corrie, not the brightest firework in the New Year’s celebration, decides to use this information to bribe Breece. Breece, of course, freaks out, and contacts Mr. Murder himself, Granville Sutter.

Sutter is more than happy to add a couple more bodies to his tally so immediately jumps into action. (Spoiler) While the first encounter ends up in Corrie’s death, Kenneth is able to get away. Because the local cops are corrupt, Kenneth must trudge through an isolated Appalachian trail to the next county over where there’s said to be a clean cop. Unfortunately, Granville will do anything to make sure he doesn’t make it.

I quite liked the first half of Beyond The Pale. I thought the idea of bribing a grave-robbing undertaker was a unique one. The necrophilia reveal was a nice touch, and provided the story with an edge these scripts don’t usually have.

In general, blackmail is a strong story device as it leads to a lot of dramatic irony and subtext. Because of the secrecy that must be maintained on both sides, there are a lot of conversations and situations that must occur on the down low. Fox example, from that point on, every scene with Breece becomes laced with dramatic irony, as he must defend his secret. When his secretary finds out, he must kill her. When the police come looking for the secretary, he must feign ignorance. On the flip side, our bribers can’t go to the police, because what they’re doing is illegal as well. That means also fighting their battles below the radar. This is usually more interesting than fighting your battles out in the open.

Unfortunately, once Granville sets his sights on Kenneth, that’s exactly where we end up, fighting our battles out in the open. All that nuance we built up is kind of thrown out the window. Beyond The Pale becomes a simple chase movie. That’s what bothered me so much. The first half made me think – pulled me into this complicated web of a story. The second is no different from one of those cheap B-Movies Paul Walker always finds himself in.

I did admire some of the structural achievements of the script. You’ll notice that Beyond The Pale has a great example of the “changing goal.” Remember, you always want your main character to have a goal. But in some screenplays, that goal will change along the way. The first goal here is to blackmail Reece. When that plan goes awry, the goal changes to getting to the next county where Kenneth can alert the clean cop to what’s going on. So while I didn’t like this part of the story, I admit it was well-constructed. Had Kenneth simply been running for his life (with no destination), I don’t think it would have been as interesting.

Another thing to note is the “Midpoint Shift.” The midpoint is that place where you want to throw something new at the characters or the story to change things up a little. You do this so that the story doesn’t stagnate or start to feel predictable. So in Titanic, the midpoint is when the ship hits the iceberg, creating a much different second half than the first. The midpoint in Beyond The Pale is obviously (spoiler) when Corrie is killed and Kenneth goes on the run.

The thing is, there’s a risk involved if you go *too* far with this shift. It’s hard enough to create one interesting storyline, so to bet that you can create two in one screenplay is a big risk. Sometimes that risk hits, but if it doesn’t, you leave people wondering, “What happened to the movie we were just watching? Where did that go?” In my opinion, that’s what happened with Beyond The Pale. What happened to that clever small town murder-bribery story I was watching?

Overall, this is one of those scripts that hovered right on the line between a “wasn’t for me” and a “worth the read.” But since the second half left me pining for the original story, I’m afraid I have to give this a “wasn’t for me.”

[ ] Wait for the rewrite.

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: While I didn’t necessarily agree with the choice that Gay and Feehan made with the sharp midpoint twist, I respected the risk. It reminded me that while having a rule set which guides your writing is a good thing, you still have to take chances, you still have to take risks. I’m reading this book “IQ84” and in it, a publisher is giving advice to a writer. This is what he says: “There also has to be that ‘special something,’ an indefinable quality, something I can’t quite put my finger on. That’s the part of fiction I value more highly than anything else. Stuff I understand perfectly doesn’t interest me.” That really stayed with me. “Stuff I understand perfectly doesn’t interest me.” I think that’s the reason a script like “When The Streetlights Go On” is so memorable. You don’t understand perfectly why you like it. You just do. And that only comes from taking risks.

What I learned 2: If you’re worried about cell phones screwing up the believability of your story, set your script in a time before they existed. Beyond The Pale is one of those stories that doesn’t work in the cell phone era. So they set it in 1973. Problem solved.