NEW Amateur Friday Submission Process: To submit your script for an Amateur Review, send in a PDF of your script, a PDF of the first ten pages of your script, your title, genre, logline, and finally, why I should read your script. Use my submission address please: Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Your script and “first ten” will be posted. If you’re nervous about the effect of a bad review, feel free to use an alias name and/or title. It’s a good idea to resubmit every couple of weeks so your submission stays near the top.

Genre: Drama/Western/Period/Mystery/Thriller?

Premise: A left-for-dead rancher wakes up in the middle of the desert with no memory of who he is. He goes off in a search to find out what happened.

About: This script came to me via my notes service.

Writer: Ryan Binaco

Details: 104 pages

So at the last second, the writer who was having his script reviewed for Amateur Friday e-mailed to tell me that he wanted to rescind his review. Maybe he was afraid of trying to follow Kelly Marcel’s amazing interview, but whatever the case, this was a nightmare scenario for me. You guys can probably tell that I’m overworked as it is. Now I’m reading two scripts for one review.

But it turned out to be a blessing in disguise. I’d just finished giving notes on a script which I thought was really interesting. I told him I didn’t know who to send it to because it doesn’t fit into any particular genre. But at the same time, it’s one of the few scripts I’ve read this year that’s kept me turning each page in anticipation.

So while the script isn’t easily categorizable (word?), there’s something about it where if it found the right person, someone who knew what to do with it, it could be special. And that’s why I decided to review it.

The script has a great opening. The year is 1846. We see the dead body of a rancher in the middle of the desert being pecked away at by buzzards, when all of a sudden his eyes shoot open. He’s still alive. The rancher stumbles up, swatting away at the birds, quickly noticing the huge gash on his head, something that whoever left him here did to him.

If only that was the worst of it. That gash – or the result of it – has left him without any memories. He doesn’t know his name, he doesn’t know how he got here, he doesn’t know anything. All he knows now is that he’s in the middle of the desert, dying of thirst, with no idea where to go.

So he just starts walking, eventually finding a disheveled man living in a cave. Cave Man, Damian, takes him in and shows him how to live off the land, even when the land has little to offer. The problem is that he’s very possessive. Every time the rancher tells him he wants to leave to find out who he is, Damian tells him that it’s a stupid idea. He has a safe place to live and is well fed. Why give that up?

Not only that, but there seems to be some animal/ beast stalking them on the outskirts of the camp. Even if Rancher did decide to ignore Damian and go out on his own, chances are this “thing” would get him.

At a certain point, however, Rancher discovers that Damian has a deep dark secret, one that explains why he doesn’t want Rancher to leave. This forces Rancher to high-step it out of there and, once again, stumble through unfamiliar terrain to find out who he is and where he came from.

Eventually, he makes it out of the desert and comes upon a farm. The farm’s owner, an older man named John, lives there with his daughter, Terry. Initially, John doesn’t believe the rancher’s story and locks him up in his barn. But over time, he loosens up and allows the rancher to stay with them. After a while, he finally decides to take John to town and find out if anyone recognizes him.

When the rancher does discover the truth, it’s not what he had hoped, but this will lead him down a new path, one where he’s accepted into John’s family. However it’s at that home that a dark secret threatens to destroy John, Rancher, and John’s daughter.

At first I didn’t know what to think of this script. Actually, that’s a lie. This script confounded me almost the whole way through. But in a good way. One of the things I’m always preaching to you guys is to take your stories in a different direction – one the reader doesn’t expect. That’s a lot easier said than done because the direction still has to make sense. It still has to feel like a logical story as opposed to a bunch of weird scenes blended together. I actually just read the first ten pages of a script over in Twit-Pitch. I was definitely surprised by the way the pages evolved, but it was too random to make sense of, too unfocused to be coherent.

With Ryan’s script here, we go from a guy stuck in the desert, to a guy being nursed back to health by a strange man, to a guy living on a ranch with an old man and his daughter. Each successive storyline was unpredictable, and yet it all fit together through the prism of this specific mystery our hero had to solve. I was really impressed by that.

Another thing that sticks with you when you read this script is Ryan’s voice. He has an uncanny ability to create atmosphere by finding the beauty (and the darkness) in seemingly mundane things. For example, he’ll highlight the way the shadows dance against the wall via moonlight right before Rancher goes to sleep.

This is another thing where if you do it wrong, it turns into a disaster. It’ll feel like a writer focusing on mundane details that don’t add anything to the screenplay other than a higher page count. But Ryan uses such a sparse writing style to begin with that this attention to detail adds instead of detracts from the story. Where this kind of thing becomes problematic is when writers are writing seven line paragraphs describing a room. Here, Ryan picks and chooses the “atmosphere” moments and keeps them very short. No more than a line or two.

Another thing I loved about the script was the way Ryan dealt with his amnesiac main character. I think when I read the logline about a man waking up in the desert with no idea of how we got there, I was expecting another Buried clone. It was going to be cliché – beginning with an intense first 20 pages, only to peter out quickly after the writer ran out of ideas.

But Ryan seems to be genuinely interested in how amnesia affects his hero. There’s a deep set need for Rancher to find out who he is. It isn’t just a function of the story – a goal without substance. It’s an organic character goal. I don’t often see amateurs caring so much about these things, yet these are the exact things that separate writers from the pack. You need to explore your characters on a deeper level and get into what they want. You have to commit to them.

And I like the little ways Ryan keeps you interested. When you have a “slow” script like this one, you must utilize tools like mystery and suspense and anticipation so that we’ll want to keep watching. Primarily, we’re interested in who the rancher is. But there are also other things that keep our interest. For example, John makes it clear that the one thing the rancher cannot do is look at his daughter in an inappropriate way. If he does, he’ll kill him.

Also, John has a room that he forbids Rancher from going into. It’s a small thing, but in the back of our heads, we can’t stop thinking about that room and what might be in it. By doing this, you don’t have to rush the script along at a breakneck speed. The mystery does the work for you. If we want to know the secret behind something, time will appear to move faster, so even though the script is “slow,” it seems fast.

I did have a few issues with the script, however. The first one was the beast at the beginning. I was never clear what the beast was – was it real or fake? To be honest, it kind of felt like one of those “film school” choices. Like, “Ooooh. Maybe the beast is him!” I don’t know, it didn’t quite fit for me.

But my big issue was the ending. At a certain point, we learn who Rancher is. Yet there were still 30-40 pages left in the script. This is always a dangerous choice. The primary problem you’ve set up at the beginning of the screenplay drives the story. If you answer it – what’s left for the audience to latch onto? Why do they want to keep reading if the main question has been answered?

For this reason, the final act essentially becomes a “wrapping up” of the family story. There is sort of a final twist, but I felt like it was telegraphed too clearly earlier on (it was really the only way for the story to go), so it landed with a whimper. This left the final act to be the weakest of the screenplay, and as we all know, you can’t do that.

But I’ll tell you this. Ryan is definitely a writer to watch out for. I’m not sure how to turn this into a sellable movie, again because the genre is so wishy-washy. But I’m hoping somebody out there “gets” Ryan and helps him maximize his potential. He has a ton of it.

This one is worth the read.

[ ] Wait for the rewrite

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: I’d be wary of answering the question that drives your story too early. It puts you in a bind for your third act because we already found out what we wanted to find out. I know who Rancher is, so I’m done. If you *do* need to answer the big question before the final act, replace it with another equally or bigger question. I think Ryan tried to do this with the mystery of who Damian was. But we already knew who Damian was, so it fell short. For example, maybe Rancher finds out what happened to him and who did it, but he still doesn’t know *why* it happened. And the *why* can be the big final act reveal.

Okay so a little background on this one. Last week I read this AMAZING screenplay, Saving Mr. Banks, about Walt Disney’s endless journey to convince the author of Mary Poppins to allow him to make a movie out of her famous character. Banks is being developed at Disney with a dream cast rumored, led by Tom Hanks as Walt Disney.

Anyway, while I was reading it, I was tweeting about how awesome it was. And some girl kept freaking out, responding to my tweets like I was announcing free money or something. She was talking about dancing on tables and just really excited. I was like, “Uhhhh, who is this freak?” I mean, I’m all for getting excited about me liking a script, but this was overboard. Eventually I figured out that person was Kelly Marcel, the WRITER of Saving Mr. Banks.

Naturally, then, I told her she had to give me an interview. I don’t know if she normally responds well to being told what to do but she agreed on one condition. That we talk about dogs and cake. Hey, you know those Brits. They can be a little [me making cuckoo noise]. I’d soon find out the complex inner workings of Miss Marcel, rooted by our shared passion for cupcakes. I explained to her that there was this place in Chicago that served this delectable cupcake called the “cookie monster” which had cookie dough baked into the cupcake. I’m pretty sure that if she wasn’t working on Banks rewrites at Disney, that she might have hopped on the plane right then. Anyway, that might help you understand a few parts of this interview. Enjoy!

SS: You had a totally rational stipulation for doing this interview. You said you’d only do it if I asked you about cake and dogs. So let’s start with cake. Do you prefer yellow cake with chocolate frosting or chocolate cake with…yellow… frosting?

KM: I just like cake; any kind of cake with any kind of frosting. It seems I have a cake-shaped hole in my life since hearing about the Cookie Monster cupcake you mentioned the other day.

SS: You’re from the UK. What’s the big difference between British dogs and American dogs?

KM: US dogs speak with funny accents, wear designer clothes and ride around in strollers. UK dogs are furless, aloof, survive mainly on a diet of bananas and can say the words “bugger” and “helicopter.”

SS: I should also point out that you didn’t want to do the interview because, quote, you’re “not interesting.” What’s not interesting about you?

KM: The only people who are interesting are the ones who have the banana helicopter dogs. Mine are both from Norway where dogs are rubbish. They just eat, sleep and shit and only know the word “ball.”

SS: Okay, now we actually get to talk screenwriting! Can you tell me how long you’ve been screenwriting?

KM: 10 looooonnnng yeeeeeeears.

SS: About how long would you say it was before you started to “get it?” And what script were you writing when that happened? Why do you think that was the script that signified your big break-through?

KM: I would say that the rewrite I did on Bronson was a significant moment for me. It forced me to overcome the paralyzing fear of beginning. I was writing on set during shooting and knowing that whatever went on the page was going to be filmed allowed a great freedom. It taught me to write with abandon and stop worrying so much – some people are going to like it, some people aren’t but at some point you have to start tapping the keys and just do it. I sound like a Nike spokesperson.

SS: In many ways, your screenwriting journey was harder than most. You not only found success, but you did so from another country! For all those screenwriters who complain that they can’t break into Hollywood because they live in Alabama or Kansas, tell us what the secret is to breaking into Hollywood from so far away.

KM: I came to Hollywood! I am very lucky to have a UK agent who also has a great deal to do with the US side of the business. Hi Lucinda! (She reads this blog.) She introduced me to Aaron Kaplan who is a producer over here (I say here because I am in LA at the moment) and he convinced me to come over and pitch Terra Nova and a show called Westbridge I had been tinkering with. TN needed an American sized budget and Westbridge was about the death penalty so they were never going to work in the UK. The wonderful thing about Hollywood is that people want you to succeed here. The tricky thing is getting through the door and for that I would say you have to have a Lucinda who can get you an Aaron who then got me a Phil and a David – who are my really good looking agents at WME (they read this too.)

SS: Okay, Saving Mr. Banks. After this script, I was in love with Pamela, Walt Disney, the script, and you. The biggest thing that stuck out to me about the script was the GREAT CHARACTERS. What’s your approach to writing characters? How do you make them come to life?

KM: You’re in love with me? I’ve been in love with you since the moment you top 25’d my script! Cookie Monster wedding cake?

I have to love my characters before I can write them – no matter how unlikeable they may appear to be. The first thing I do on any project I write is I put pictures of all the characters on the walls of my office (or wherever I am working.) In this case the film was based on real life events so pictures of Walt, PLT, the Shermans were easy to find. If it’s a fictional character like Ralph I’ll find a picture of someone I imagine he looks like. I will also surround myself with anything else that is useful so… pictures of the Disney lot, as it was, exteriors and interiors of PLT’s house. I want to inhabit the world I am creating from the inside rather than as an onlooker. For me that’s the best way to crawl into the people of the piece and feel like I am there with them. I hope that it can then become an encompassing experience for the reader too. Everything, for me, starts and ends with character; I am definitely not a plot driven writer.

SS: I discussed in my review of the script that the main character is pretty darn unlikable. You must have been aware that this might be a problem. Did this worry you? How did you approach it so that we would root for Pamela?

KM: I think if I had allowed myself to think that people would dislike Pamela I would never have taken on the task. I approached her with a great feeling of tenderness; I was moved when I read her story and I enjoyed how ornery she was. I always wanted her to be a character you loved to hate but whom, over time, you came to understand was damaged and could forgive even if it was just a little. Creativity comes from all sorts of places and I admired Pamela for being able to create a character so beloved out of so much pain. John Lee Hancock talks about how her life was shards of glass but that once you put those shards into a frame they become a thing of beauty. I guess that’s what we both hope the audience will see too.

SS: I usually hate flashbacks. But I loved these. How does one make flashbacks work and, in general, when do you advise writers use them and when do you advise users avoid them?

KM: I hate flashbacks too. I still question myself about whether I could have told the back-story differently. In this instance though, I like to think that they work because, despite their constantly informing the present, they actually feel like a film in their own right. At least I hope they do!

SS: You also have some great secondary characters here, such as Ralph, the driver. Do you always put a lot of stock into secondary characters? How do you approach them?

KM: Secondary characters are so much fun. They don’t have the enormous weight on their shoulders that your leads do so those are the characters with whom you can play a bit more. In the Ralph instance, he didn’t actually come along until I was way into the writing. It’s weird saying that because he feels like such an integral piece of the puzzle now. I was starting to feel that there was no one in the story that PLT wasn’t damaging in some way and I didn’t want to be untruthful – in reality she had a lot of friends who loved her. I wanted her to have at least one ally or someone who just wasn’t affected by her in the same way as everyone else.

Hang on! I’m blathering on about Ralph and that’s not even the question you asked me! I do put a lot of stock in secondary characters they’re the ones who let you see a different side to the situation or person in the situation and I approach them as deeply as I do every other character. However small, their story must also come full circle.

SS: I drop-dead LUVVVED that final Walt Disney monologue. You have to tell me what the secret is to writing a great monologue. It’s something that’s not talked about a lot in screenwriting circles, but it should be, as I rarely see it done well. Do you have a checklist or do you just roll with it?

KM: Oh maannn, that’s a hard one. I think doing a monologue – particularly where you are trying to convince someone of something – is a bit like being a lawyer putting together a closing speech. You have to be manipulative without it seeming like you are. I think they are hands down the hardest thing to write and they really only begin to come together in the re-writing– way into the re-writing. I will be working on that monologue up until shooting and probably never think it’s right. It’ll be one of those situations like when you’ve had an argument and then days later you think “Shit! I should have said that!” ten years from now I’ll be like “I’ve got it!”

SS: Let’s switch over to TV for a second. You created Terra Nova, a HUGE TV show. I don’t know much about the TV world but I know getting a show that huge on the air is difficult. Can you tell me how you did it? I’m so curious.

KM: I wrote a 15 page and a 30 page bible that my UK agent (hi Lucinda!) was convinced she could sell in the States. I thought she was out of her mind. I didn’t realize she had the powerhouse that is Aaron Kaplan in her back pocket and the rest is history. It’s really about those two people and their connections and ability to get me into the networks with an idea. Aaron helped the show along by bringing in a much more established show runner – Craig Silverstein – to pitch with me. I was a nobody at the time, so without Craig I don’t believe anyone would have let me in the toilets let alone the meeting rooms!

SS: What’s the big difference between writing a movie and writing a show like Terra Nova? What are the unique challenges that you only get in the television world?

KM: With television you are writing to commercial break. It’s a four-act structure and every act needs to end with a cliffhanger that makes the audience want to come back and that is HARD to do. It’s entirely different to a film script, which has more of a slow burn and has less of the big jagged MOMENTS you need in television, network particularly. I am fascinated by watching Vince Gilligan do episode after episode on Breaking Bad and making it surprising, exciting and fresh every time. That’s writing as far as I am concerned; that’s where the really hard work is.

SS: Because I’m a selfish person and I need constant gratification, I have to ask you this. You’re a fan of Scriptshadow. You’ve been reading it for a long time. Was there anything you read on the site that really helped you as a screenwriter, in particular with Saving Mr. Banks? If not, could you lie and make something up?

KM: Yes. It really helped to know that someone out there could get their hands on any draft of any script at any time. It filled me absolute dread that one day it might be my script. Basically you terrified me into trying to be a better writer.

SS: What’s the hardest thing about writing for you? How do you combat it?

KM: Beginning. Always beginning. I will do anything…literally anything if I can get out of starting a script. Washing up suddenly becomes a joy. The blank page is my enemy and it’s normally not until there is absolutely nothing left to procrastinate about anymore that I click the dreaded green f.

SS: Finally, I figured I’d pitch you a project we could co-write together. Note that I incorporated your two favorite things. My idea is about a dog who gets jealous that his owner is getting married so he steals the $20,000 dollar wedding cake the day before the wedding. What do you think???

KM: Is it a Cookie Monster wedding cake?

The creator of Mad Men decides to tackle his passion project while on hiatus from the show.

Genre: Drama/Comedy

Premise: In the vein of Sideways, an alcoholic weatherman and his bi-polar unemployed best friend find out that the friend’s recently deceased father has left him a small fortune.

About: Matt Weiner, of Mad Men fame, writes a script that is just about as far away from Mad Men as Don Draper is from fidelity. Maybe that’s because Weiner has been writing and rewriting this script for over a decade! This is his dream project, and Mad Men’s success has finally allowed him to make it.

Writer: Matt Weiner

Details: 120 pages – August 21, 2011 (This is an early draft of the script. The situations, characters, and plot may change significantly by the time the film is released. This is not a definitive statement about the project, but rather an analysis of this unique draft as it pertains to the craft of screenwriting).

I am here!

So are you guys.

What a way to start this review.

I definitely need SOME way to start the review because…wow…what a weird script. Talk about a lack of structure. I’d categorize this more as two friends bumbling around for 2 hours than I would a movie. Stuff *does* happen in “Here,” but not often. And when it does, it always happens too late. I mean I guess the first act turn – the reading of the inheritance – happens on page 30, close to where the end of the first act should be in a 120 page screenplay, but it sure felt closer to page 50. And that, again, is because so little happens before it.

Remember that the placement of your first act turn should be determined by the amount of plot you need to set up. If, for example, you’re writing a movie like Inception, which has a ton to set up, then your first act turn is going to come later. But if you’re writing something with very little plot – say “Dumb and Dumber” – then your first act should end sooner. If you’re just hanging around in your first act until page 30 because the screenwriting books tell you to, then your first act is going to draaaaag.

And look, I’m not telling Matt Weiner how to write. The great thing about Mad Men is that it doesn’t follow conventions. It makes unexpected choices. The tone and the feel of that show are divinely unique. But I’m not feeling the desire to create something like Mad Men here.

Our heroes are slightly non-traditional, I suppose. There’s Steve Dallas, a weatherman who moonlights, sunlights, and dusklights as an alcoholic. And then there’s Ben, a bi-polar nutbag who sits in his apartment all day and does nothing. While they’ve known each other since high school, their friendship is primarily driven by a desire to abuse illegal substances, which they do a lot of.

Eventually, Ben gets called back to their home town for the reading of his father’s will, to which Steve attends. It’s there where they meet Angela, the father’s widow. Oh yeah, Angela’s in her twenties. Ben’s dad was in his 70s. Doesn’t take a math major to figure out our dear young Angela is probably a modern day gold prospector.

However, the estate reading turns everybody’s world upside-down when the land, the house, and the grocery store are all left to Ben – an estate totaling 2.5 million dollars! Ben’s sister is furious since she knows how much of a fuck-up he is and that he’ll likely squander all of it. But Angela is strangely unaffected by the reading. Which intrigues Dallas, who loves having sex with intriguing woman.

So Dallas makes an excuse to stick around, “comforting” the grieving Angela. But Angela’s the one woman who’s not falling for his charm and good looks. Which is really all Steve has. So when he can’t depend on that, what can he depend on? The only way to find out may be to sober up for the first time in 20 years, and it ain’t clear if Steven’s going to be able to do that.

Someone told me after reading this that it’s clear a TV writer wrote it. While I’m not exactly sure what that means, I think I have an idea. There’s a scene early on where Ben talks for a really long time about being a vegetarian. I’m not sure what the point of it is, but I know it doesn’t push the story forward. It feels like one of those scenes writers write solely because they’re interested in the subject matter and want to get it into their screenplay – regardless of whether it has to do with anything.

Since TV storytelling evolves at a more leisurely pace, a scene like this might work. But in movies, where every scene must be an integral piece of the puzzle that thrusts the story forward, a scene like this dies on the page. And that was my issue with the first act. There were a lot of scenes like the vegetarian one.

But I think the thing that really baffled me was the characters. I’m still not sure who the protagonist was in You Are Here! The script starts out focusing on Steve, implying to us that he’s our main character. But this is actually Ben’s story. He’s the one whose father dies. He’s the one who all of the important shit happens to. So shouldn’t we be starting with him? Except we can’t start with him. He’s the wacky sidekick. So we start with Steve, even though Steve has absolutely zero at stake with anything in the movie.

I get the feeling that someone like Weiner would read this and roll his eyes, maybe even laugh – the implication being, “People like you are idiots. You don’t analyze this shit. Just enjoy the fucking story.” But that’s the thing: I had a hard time enjoying the story because I couldn’t even understand the roles of the characters.

There’s a segment in You Are Here, for example, where Steve takes off back to the city for awhile, and we stay with Ben and Angela. Wait a minute. WHAT?? So we established that we couldn’t start with Ben, even though his life is pushing the plot forward, because he’s too much of a wacky sidekick. But now it’s decided, midway through the movie, he’s going to be our main character?? I’m sorry but this sounds like a writer who couldn’t make up his mind. And what the hell happened to Steve?? Why did he LEAVE?? What character just LEAVES a movie??

As far as our character triumvirate went, Angela was probably the most interesting of the three. I liked that Weiner avoided clichés with her. We assumed Angela was a gold digger. She wasn’t. We assumed she was selfish. She taught special-ed children. We assumed she would fall for Steve. She didn’t. The reason anything at the house worked was because we didn’t know what to expect from Angela.

However, at a certain point, Angela became the epitome of what was wrong with You Are Here. I couldn’t get a handle on her. Just like I couldn’t get a handle on any of these people. Steven is an alcoholic. But I didn’t definitively know that until the third act when Angela literally says it. I just thought he partied too much. Ben starts the movie beating the shit out of Steve, then inexplicably bursting into tears. In retrospect I suppose this was to demonstrate his bi-polar personality, but at the time it was bizarrely confusing. And with Angela, I couldn’t figure out what she wanted. She seemed confused a majority of the time.

There are some good things about You Are Here. Stuff gets fun when the sister challenges the will. And I like the idea of Ben stuck in this house with a woman who was the wife of a father he barely knew. It made for an interesting dynamic. Especially with weirdo Steve popping in every once in awhile. I just wish there was more of a structure to the story. Everything felt too fast and loose. And in the end, I wasn’t sure what I was supposed to take away from it.

[ ] Wait for the rewrite

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Look out for “Mouthpiece scenes.” These are scenes where you use your characters as a mouthpiece for your own theories and ideas. They never feel natural because we can tell that the character has been replaced by the writer, who just HAS to get out his feelings on this one topic. These became popular in the 90s after the famous “Why should I tip?” monologue in Resevoir Dogs. But now they just stop a screenplay cold. That was my problem with the early Ben vegetarian scene. I read it and thought, “This has nothing to do with anything.” I guess it told us Ben was a vegetarian but we could’ve easily achieved that by showing Ben refuse meat on his sandwich. The point is, mouthpiece scenes tend to feel unnatural. If you absolutely have to include them, make sure the scene is pushing the story forward. Otherwise, they’ll stop the story cold.

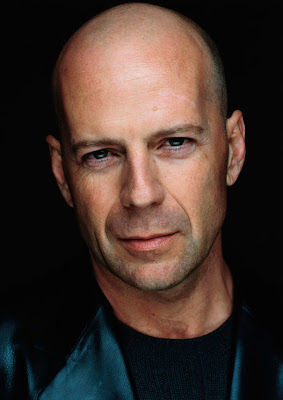

There may not be any White Houses exploding today as previously planned, but we do get the man who played the part our White House exploding screenplay was inspired after. That’s right – John McClane, aka Bruce Willis, adds another film to his arsenal.

Genre: Thriller

Premise: When a fireman witnesses a gang-murder, he must stay alive long enough to testify against the leader.

About: Tom O’Connor is the same writer who brought us the Black List script I reviewed/liked a few weeks ago called “The Hitman’s Bodyguard.” Fire with Fire has actually already completed production and stars Bruce Willis.

Writer: Tom O’Connor

Details: 105 pages – 5/12/10 (This is an early draft of the script. The situations, characters, and plot may change significantly by the time the film is released. This is not a definitive statement about the project, but rather an analysis of this unique draft as it pertains to the craft of screenwriting).

So the other day I was reading some Twit-Pitch First 10 Pages, and I was feeling bad that I was reading them so late. I was exhausted. I was slow. I kept thinking I should be reading these under better conditions. But the more I thought about it, the more I realized that these are the conditions most scripts are read under. Readers, and really anybody in Hollywood, are likely reading your script when they’re tired. Industry folks are notorious workaholics (as I’m discovering more and more), and always trying to fit that one more call in, that one more script in. Which means your script is probably being read in that 45 minute period between putting the kids to bed and brushing one’s teeth.

But in this case, I want you to magnify that exhaustion by a thousand – That’s where I was when I opened this script. I’d actually planned on reviewing a different script (let’s just say there was a White House involved) when the writer politely asked me to hold off for awhile. (note: No more live-tweeting script reviews!) Which meant I had to add another script onto an already endless day. Honestly, I think I started reading it at 3:30 a.m. All I could think about was the sweet nectar of my freshly washed sheets against my back. I could feel the coolness already. Oh sweet bed sheets. I love you.

So if ever there was a script that didn’t stand a chance, it was this one. But guess what? It pulled me in almost immediately. THAT, my friends, is good writing. Being able to wake a reader from his impending slumber. And it proves my theory – which is that no matter how distracted or tired or uninterested a reader is, if you write something good, you can get’em. So when you’re writing your next script, ask yourself that question – “Would a dead-tired reader stick with this?” Cause that’s likely your audience.

Anyway, Fire with Fire introduces us to Jeremy, a firefighter who’s so dedicated to his job that when a bar goes up in flames, he runs in to save a case of scotch for he and his buddies. In other words, if you can’t take the heat then take the scotch from the kitchen.

Afterwards, he and his boys decide to celebrate with some early morning snacks. So they head over to the local convenience store and Jeremy goes in to snag some food. An overworked Latino man and his teenage son are cleaning the place when a trio of very bad looking men enter. There’s Boyd, Sean, and Neil Hagan, the leader (a man with Arayan tattoos bursting out of his suit).

Doesn’t take long to realize these guys aren’t here for a Big Gulp.

Turns out Neil wants to buy this store as it’s a perfect location for his drug business. The owner stands strong, though, saying he’s protected by a Latino gang and that they should leave. Hagan responds by SHOOTING HIS SON and then him. Sort of an odd negotiating tactic if you ask me but this Hagan guy’s a bit unconventional.

With Jeremy being a witness, he’s now collateral damage. But a nifty move at the last second allows him to escape. If only that were the end of it. The Feds have been trying to catch this Hagan fellow for years. And now that they have a witness to one of his murders who’s willing to testify, Christmas has come early. But that means Jeremy will have to go into witness protection until the trial.

So he’s whisked off to the middle of Buttfuck, Nowhere, supposedly safe from the reaches of Hagan, especially considering he’s now in jail. But it doesn’t take long for Hagan to work his magic and find Jeremy. He then sends two hitmen to erase the problem.

Jeremy is able to escape, but soonafter, accepts the truth. Jail or no jail, this man will hunt him down until he kills him. So Jeremy does the unthinkable. He goes on the offensive – He’s going to kill Hagan. This seems insane at first, but it turns out that rival Latino gang is more than eager to help him out. And that just might be enough to tip the scales.

Lots of good things about this script. First thing I noticed was the plot device O’Connor used to frame the story – a trial. Specifically getting to a trial where one man could prove another man guilty. Just like The Hitman’s Bodyguard! This was not by accident. Notice how the device creates the trifecta of a goal, stakes, and urgency. The goal is to make it to the trial. The stakes are if he doesn’t, Hagan goes free. And the urgency is the ticking time bomb of the trial, coupled with Hagan’s men on his tail. I’m not surprised at all that O’Connor leaned on this device a second time, as it’s an effective way to frame a story.

O’Connor also followed the old Scriptshadow staple of making your bad guy REALLY BAD. The badder he is, the more we’ll want to see our hero take him down. Hagan shoots a fucking father and son without blinking. That’s bad. But note how he did it. Anybody can have the bad guy shoot someone to make the audience hate him. That’s a cliché choice and probably won’t resonate. So O’Connor has his bad guy shoot the man’s son first – right in front of him! That hits us way harder (a father watches his son get shot right in front of him!!).

The script had some really cool moments as well. I thought the convenience store scene was inspired. I mean you were IN that store, BEGGING for a way out just like Jeremy. That’s the scene that officially woke me up from my slumber.

Another great moment is the line-up scene. They put Hagan in a lineup with the classic one-way glass and Jeremy having to identify him. Each man is asked to step forward and read out the line that Hagan uses at the store. When Hagan finally steps forward to read the line, he reads his own line instead: JEREMY’S NAME AND ADDRESS! It was one of those f*cking awesome “movie moments” that people are going to be buzzing about when they leave the theater.

But Fire With Fire started running into problems in the second act. If you read the site often, you know I like clean narratives. I like when we know what the story is about and where it’s going. For example, The Disciple Program. We know what that story is about. It’s about a man getting revenge on the men who murdered his wife.

With Fire with Fire, the narrative kept changing. At first I thought we were in a firefighting movie (it’s called Fire with Fire, it’s about a firefighter, and the first scene is a fire). Then it becomes a witness relocation movie. Then it becomes a revenge film. Then it turns into a gang war film. I’m not saying you can’t change directions in a script. We were just talking yesterday about doing this at the midpoint. But if you keep doing it, the reader starts becoming confused. I know I was. “What kind of movie is this exactly?” I kept asking. You really have to be a great writer to pull this off and while O’Connor is a very good writer, I would’ve loved to have seen more focus in this area.

It’s too bad because the script started off so awesome. I was thinking it could be a classic. Then it never quite decided what it wanted to be. Still, the story’s fun enough to keep you entertained. And there’s easily enough here for a recommendation. It just didn’t quite reach the heights that it could’ve.

[ ] Wait for the rewrite

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Don’t blow your best scene on the first act. A lot of writers – especially young writers – make the mistake of putting their best scene in the first act. The problem with this is that every other big scene afterwards will feel like a letdown in comparison. If you’re going to put a great scene in the first act, then you have to be willing to top it again and again throughout your script. That was an issue I had here. The scene I remember most is the convenience store scene. And it happens inside the first 15 pages. You’re now going to have me sit around for another 100 pages and not read a better scene? I’m gonna feel let down. So when you get to those big scenes in your script, always try to top yourself from the previous big scene. You want your best most powerful stuff happening in the last third of the script if possible.

The Black List strikes again with this high-octane sci-fi thriller. But does it have the stamina to make it to the finish line?

Genre: Sci-Fi

Premise: The United States is attacked by an unknown enemy that is vastly superior to them in every military category. Who could it possibly be?

About: On A Clear Day finished on last year’s Black List. It currently has Jaume Collet-Serra attached to direct. Collet-Serra was the director of Orphan and Unknown. He is also attached to direct the long-gestating live-action adaptation of Akira. Ryan Engle, the writer, gets the Fascinating Adaptation Award of the year, as he adapted “Rampage.” You guys remember that one? The video game where monsters leapt onto buildings and smashed stuff up? I would’ve loved to be a fly on the wall during those development meetings.

Writer: Ryan Engle

Details:116 pages – undated (This is an early draft of the script. The situations, characters, and plot may change significantly by the time the film is released. This is not a definitive statement about the project, but rather an analysis of this unique draft as it pertains to the craft of screenwriting).

You guys know how I feel about How It Ends. L-O-V-E luv it! Anything where the end of the world is coming and you gotta figure out a way to stay alive is a conflict mating call. Unless, of course, you do it realllllyyyyy slowwwwwwwly. I won’t mention any scripts by name but I think you know which end of the world script I’m talking about.

Anyway, if How It Ends had one of those cousins that looks so freakishly like you that you start seriously considering you’re a clone, On A Clear Day would be that cousin. The two scripts start very similarly. In fact, they start in the exact same city – Seattle! Coincidence?

So Seattlein Peter Fox is a normal family guy who, oh yeah, just lost his job. Not ideal when you’re trying to support two daughters and a wife. Oh yeah, and you have another one on the way, which you don’t know about yet because your wife, Molly, hasn’t told you. Things are looking very bleak on the economic front for the Fox family. The hare has passed them by.

That’s the one good thing about a bloodthirsty attacking army – it puts things in perspective. All of a sudden, a middle-management job with above average health benefits doesn’t seem so important. Indeed, just minutes after Molly comes back from dropping the kids off at school, explosions start ringing out everywhere.

Peter and Molly know that their immediate job is to get back to that school and save their daughters. But as soon as they get outside, they realize how bad it is. There are explosions happening in EVERY DIRECTION. Operation Daughter Save is too important though so they head into the heart of the city.

That’s when they first see the enemy. A tank. Shockingly huge. All black. Sleek. Blowing everything to pieces.

*They* may have not figured it out yet, but us sci-fi geeks have. The future has sent back an army to take over the past! Eventually, Peter and Molly catch up to us, but that doesn’t make things any easier. In fact, when Molly gets injured, they’re forced to split up. And that’s when Peter sees the extent of the attack – the army is carting everyone away in trucks. Something tells me they’re not getting a sightseeing cruise around Pugent Sound.

But it’s about to get way worse, and you can blame James Cameron for that. Our Terminator-inspired army is hunting down specific people who could cause them harm in the future – and PETER IS ONE OF THEM! Also, because they’re, you know, from the future, they know where Peter’s going to be before he does! Somehow, then, Peter has to circumvent this army and these odds to get his wife back and save his daughters. All before Future Army And Friends destroy the city.

This script took you by the tail and swung you around like a giant ferris wheel. The first 25 pages were probably the best I’ve read all year. I didn’t know what was going on (hadn’t read the logline) so I was having a blast trying to figure out who this mystery army was.

And it was just so easy to read!

That’s something I’ve been appreciating more and more lately: easy to read writing. I’ve been reading through all these Twit-Pitch scripts and it’s strange how some of them allow your eyes to just fly down the page while others keep you reading the same paragraphs over and over again. And it’s not even obvious what’s wrong. They’re competently written. It’s just the way the sentences are constructed is clunky. Either there’s too much information or the order of the information is off or something. It’s unnecessarily difficult.

But the thing I really loved about this script was that Engle always had a huge goal pushing the characters forward. AND… as soon as that goal expired, he’d replace it with a new goal. So there were never any lags in the script. It always moved because his characters always had something immediate to do.

So it starts out with Peter having to save his kids. That’s his goal. But on the way there, Molly gets injured. So there’s a new goal: Get her to the hospital. Once at the hospital, they get split up because the Army moves in. So there’s a new goal, he has to find Molly. Once he does, we go back to the original goal. They have to find and save their kids. This process is essential for a movie like this because a movie like this needs to move. If you don’t have a sense of urgency in a movie where the United States is being attacked, then you probably haven’t written a good script.

For the record, setting new goals for your characters every 10-15 pages for is one of the easiest ways to keep the pace of your screenplay brisk. I read scripts all the time where writers don’t introduce a new goal right after they’ve finished a recent one and let me tell you, those scripts get boring REALLY fast. You ALWAYS want to have your character driving towards something. The second they’re not, they’re passive. And passive people are boring.

I do have to admit, though, that the pace got a little exhausting towards the end. I felt like I was on the 23rd mile of a 25 mile marathon and my legs finally gave out. It’s strange because the pace was “Day’s” biggest strength, but at a certain point we needed to relax. Even Weekend-long benders in Vegas require some nap time.

Another problem was that the first half of the script was so good, it was almost impossible for the second half to live up to it. In any “on the run” script like this, the big danger is that things are going to get repetitive. To prevent this, you want to introduce a new element at the midpoint that adds some sizzle to the story. I always use Pitch Black as an example of this. In the first half, they’re discovering the world and looking for a way off of it. In the second half, darkness comes and millions of flying beasts shoot out of the middle of the planet to make that search infinitely more difficult. That’s what saved that movie from being repetitive.

I didn’t get that here so the redundancy factor kicked in.

Still, this was just so well-written, so strongly paced and such a structurally impressive screenplay, that in the end, the positives outweighed the negatives. And I loved the idea of the future attacking the past. I’ve been waiting for a script to take advantage of that idea for awhile.

So I would recommend this one – especially to sci-fi geeks. If the second half had given me a little more, this may have finished a rating higher.

[ ] Wait for the rewrite

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: What I liked about this script was that it never let the characters off the hook. There’s a moment where Peter’s survived an extended battle with a soldier in the hospital. As soon as he kills the guy, however, he hears two more soldiers coming down the hall. So he hides behind a corner. In almost all the screenplays I read, after an extended battle like this, the writer lets the character sneak away. Engle doesn’t. The new soldiers spot Peter immediately and come after him. It’s a small thing but it’s what makes this script so intense. Nobody’s ever allowed an easy out. Every single moment is difficult. – So always look to make things difficult for your hero. Never let them off the hook!