If there’s anything I learned, it’s that not even the best logline consultant in Hollywood can compete with a brain-trust of 100+ screenwriters. You guys killed it. I personally liked Katie’s…

A repressed war widow awakens naked in the snow on a military black site and must outwit her ruthless father’s vengeful soldiers when she realizes the carnivorous feline they are hunting is her.

And DG Burton’s best…

A repressed young widow awakens naked in the snow on a military black site and discovers soldiers have been torn apart, she has no memories of last night, and she’s being hunted by the Marines’ most ruthless general – her father.

Now if you could just come up with a logline to erase daylights savings time, I would pay all the money in the world to see that movie succeed! You certainly did better than the movies at this weekend’s box office. This was supposed to be the big Dune 2 opening weekend but the film, like many others, got pushed back because of the actors strike.

It’s so hard to promote a big movie when your stars can’t get out there and make headlines for you. I enjoy the backup plan – sending directors and writers out there – because literally everything they say is more interesting than what actors say. But you can’t deny the fact that, without actors to remind us that their movies are opening, the movies don’t seem as big.

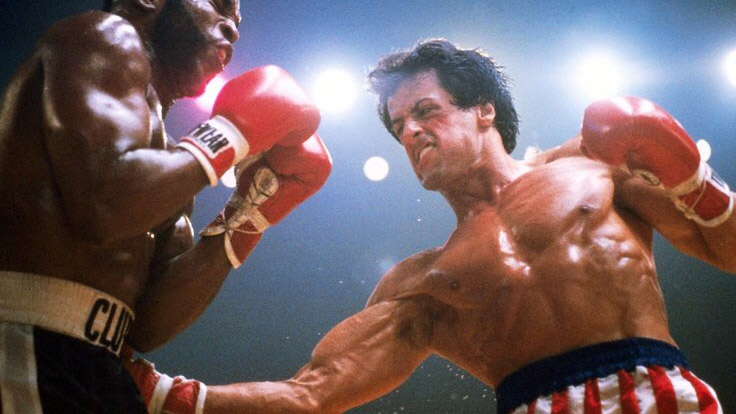

Speaking of someone who’s a writer, director, AND an actor, Sly Stallone has been in the news a lot, with his docu-series premiering on Netflix. What’s interesting about Sly is that he should be one of the richest people in Hollywood. And yet the rumor is, he’s out of money. That’s why he agreed to this docu-series. It’s why he has that Kardashian like show about his family on Paramount Plus. The guy is hustling.

Most of this stems from the fact that he doesn’t own a single sliver of the Rocky franchise. You can’t really fault him for that. He notoriously stood strong when he made that Rocky deal, insisting that he be the star. Which, if he didn’t do, there’s a good chance we wouldn’t know who Sylvester Stallone was today. But he mistakenly didn’t obtain any of the rights to the film, which means he hasn’t gotten paid a single dime outside of his acting fee from the billion dollar franchise.

Still, the dude has 75+ IMDB credits. How are you struggling to pay your bills?? Seems like there’s some serious money mismanagement there.

The reason I wanted to bring up Stallone is that he recently revealed that his first draft of Rocky had a different kind of Rocky. Rocky was a brute. Rocky was a tough guy. Rocky beat you up and didn’t feel bad about it. It wasn’t until a lady friend of his read the script and cried to him that she hated Rocky because of how mean he was, that Stallone decided to change the character into the more lovable iconic character we know today.

His very first change, which was actually suggested by the friend, was that instead of beating up the guy who couldn’t pay his loan, he let him go. The guy even offers Rocky his coat to help pay but Rocky lets him keep it. From there, Stallone just paid more attention to how Rocky acted. He wanted him to be sweeter instead of meaner. As a result, an iconic character was created.

I wanted to highlight this because there’s this erroneous belief that you win “screenwriting street cred” by creating an unlikable character. But in this case, it is literally the thing that would’ve sent this movie down a path where we never would’ve heard of it, versus what it became, which is a billion dollar franchise.

And when we talk about likability, it doesn’t have to be like in Adam Sandler movies where the ten-cent screenwriters he uses have his character save 20 lives before he’s even reached the inciting incident to MAKE ABSOLUTELY SURE you love him. With Rocky, he’s just an understated nice guy who cares about people. He’s not over the top about it. That’s just who he is.

Remember that going forward. You don’t need to have your character save the world for us to like him. He can just be nice! It’s not complicated.

Shifting focus from the movie world over to the TV world, I stumbled upon the latest trailer for a Marvel TV show. It’s a show called, “Echo.” Before I get into my thoughts on the trailer, I know one of the writers on Echo (who’s an AWESOME writer by the way – one of my favorite unknown writers out there). I am not blaming him or any other writer who gets hired to write a Marvel show. I would cash that same check in a heartbeat.

My problem is more with the state of TV in general. Cause when I saw this trailer, I didn’t feel anything. There’s a woman. She had a tough childhood. Now she’s some sort of fighter as an adult. There’s an intensity behind the presentation of her story and it looks totally fine. There’s nothing wrong with this show at all. But it doesn’t stand out in any way. It doesn’t MAKE ME WANT TO WATCH IT.

Echo is a symbol for where the TV industry is today. We’ve gotten to the point where it’s nearly impossible to stand out from the pack. If Marvel, which can afford to put 100 million dollars behind a show like this, can’t get anyone excited about watching it, where are we? We are in the most saturated TV market ever where every show feels the same in the sense that there’s nothing exceptional enough that you actually label it a must-watch.

This begs the question: How do you write a TV pilot in 2023 that stands out? Is it even possible?

As far as I can tell, there are several show-types that get interest. The most prominent are the IP shows that have passionate fan bases. I’m talking Wednesday on Netflix or The Last of Us on HBO. These are useless to aspiring screenwriters, though, because we don’t have access to those properties.

Then you have the high-concept stuff, like Squid Game, Yellow Jackets, or Stranger Things. These are super-expensive but, if you can come up with one, they’re great because they’re the only ideas that can compete with those IP properties. Unfortunately, their cost scares a lot of potential suitors away.

And, finally, you have the word-of-mouth shows, the shows that become hits because of how incredibly well-written they are. I’m talking about the White Lotuses, the Successions, and the Bears. Unfortunately, it’s impossible to strategize around writing one of the greatest shows ever. So it’s yet another arrow we can’t add to our quiver.

But there is one final category which, I believe, is the one that best gives an aspiring screenwriter a shot at writing a show that stands out. And I call it, “The Voice Show.” No, I’m not talking about spinning chairs and overly charming country singers and golden tickets. I’m talking about a show that demonstrates your unique voice. Some recent examples would be Fleabag, Euphoria, Atlanta, Severance, and Beef.

There’s something unmistakably unique when you read these pilots and it’s not as difficult to pull off as you may think. Having a distinctive voice boils down to identifying what it is about how you see the world that’s unique and leaning into that as aggressively as possible. If I’m a Korean-American man who suffers from anger issues, that’s a great starting point for leaning into my voice. Which is how “Beef” was conceived. That show is less about the story than it is about its creator. And how that creator, Lee Sung Jin, sees the world.

The second ingredient to writing one of these shows is to be weird. To be awkward. It’s fine to cover your everyday existence in these shows. You just can’t do it in an expected fashion. Every interaction Fleabag gets into in her show is awkward. There’s one point where she’s in a job interview and inadvertently propositions the interviewer, then is forced to backtrack. We’re all weirdos deep down. We have weird thoughts. We get in weird situations. LEAN INTO THAT WEIRD. That’s how you’re going to make your pages read different from everyone else’s.

The third ingredient to these shows is to take from your own life. You should be using your own life to power all of your writing, of course. But it’s especially important in this type of script because one of the easiest ways to stand out is to chronicle things that nobody else has seen before. And since your unique experiences contain a myriad of specific moments, you want to mine those moments as much as possible. In Fleabag, that heartbreaking Phoebe Waller-Bridge miscarriage dinner with her sister was, supposedly, based on real life with someone she knew.

The final ingredient to writing these shows is to be achingly truthful. When you’re writing big Hollywood movies, you’re often a slave to the plot. You have to have that big twist at the midpoint for example, so you dance around in your mind for a few days until you come up with that twist. You don’t do that here. You lean into the truth. If a character in the throes of drug addiction is confronted by her friends and family, you better have that drug-addicted character act truthfully. That approach led to one of the best episodes of Euphoria when Rue was confronted and she did what any addict would do in that moment. She RAN.

There has to be an element of rawness and realness on the page to truly stand out from the pack. And, unlike movies, which work better within the construct of sexy concepts, TV is more about character and, therefore, more conducive to this sort of writing. By the way, I’m not saying you can’t succeed by writing the next CSI or the next Stranger Things. All I’m saying is that if you want to write something that has the best chance at standing out from all the other scripts that these production houses and studios read? The Voice Script is the number one way to go.

Do you have one in you?

Today, we’re going to do something different. With loglines being such a hot topic on the site, I thought I’d take you through a recent logline consultation of mine so you can see the thought process I go through when I develop a logline. This logline comes from a frequent contributor to the site, David Laurie, who came to me with his logline for, “She’s Got Claws.”

To give you some context, I have two logline consult options. The first is a basic option ($25) where I give you a single e-mail analysis of your logline, a 1-10 rating, as well as a logline rewrite. These are great if you haven’t written the script yet and you just want to know if you’ve got a good movie/show idea.

David ordered the deluxe option ($50) which is mainly for writers who have already written their script and need the best logline possible for querying purposes. The deluxe option gets you as many e-mails as it takes until we get your logline right.

I’m including David’s consult because most of my clients get what they want after 4 or 5 e-mails. But David doesn’t mess around. He gets into the nitty-gritty. And, you know what? I’m glad. Because if we have to push it to the absolute limit to get a good logline, I’m willing to do it.

If you want a deluxe logline consultation, I’ll give you a $10 discount if you mention this post. E-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com. Okay, settle in and buckle up. Let’s get to the consult!

**********

Original e-mail from David Laurie

I am struggling with She’s Got Claws’ logline.

Although the script is pretty damn tight IMO.

It’s a monster movie. Basically a werewolf movie but my spin delves wayyyy back into legend. The Nephilim are an enhanced superhuman/ubermensch race mentioned in the Bible. Some translations have them as part animal.

So in my prologue, DNA extracted from a young girl in wartorn Afghanistan, is used for a serum that brings out the animal closest to your true self via a werewolfy transformation.

In the case of meek, buttoned-up, no-make-up-no-hair-products war widow HOLLY, who’s been put-upon all her life, this creature is a powerful, majestic and extremely savage LIONESS.

She wakes on a snowy roof in a rundown Alaskan town, naked and bloody, with no memory of what happened. Surrounded by soldiers hunting a wild animal that escaped and has killed several men overnight.

Holly must evade the soldiers, seek clothes, refuge and help. She soon realises the animal they are hunting is her. And the General in charge of the hunt is her father. And the rundown town is an abandoned army facility, now a blacksite. Rumours of locals going missing have been piling up.

Holly has never changed before. It is new. She knows the answers lie in the blacksite. Obvs. She would prefer to run away but the Alaskan Spring Thaw has blocked all the roads out of town. And she can’t get over the idea that her own family is involved.

So it’s an empowerment story of a woman facing up to her family, who despite being human, are the real monsters (maaan).

There’s a budding romance in there amid lashings of dark humour and super gory violence.

Tonally I am going for An American Werewolf in London eats Memento

It is pretty funny but it’s NOT a comedy. It reads as a tense, urgent, psychological thriller. As per usual for me. Lots of running around, bullets and biting heads off. The dark gallows humour matches the life-or-death situations.

What is less usual for me is the plot is pretty simple. Woman is hunted. Escapes. But turns tables and seeks out the hunter. Doesn’t like what she finds. Gets mad. Gets even. Pulls a lot of heads off. Learns to live with it.

I started a little debate yesterday on the topic of WHAT IS SCARY?

with a side of Is SHE’S GOT CLAWS a HORROR movie?

I was knocked by your #1 rule of Horror. Three scary scenes. I wondered: are the set pieces scary enough?

I have since pumped them up.

But does that make it A Horror Movie? It’s a tense, violent jump-scare-tastic monster movie with a dark emotional undercurrent, so, after a crisis of faith, I have decided yes, of course it’s fucking Horror.

But my logline is not cutting it

So. I am currently at

On a desolate Alaskan military base, a timid war widow transforms into a savage lioness. Waking up as her old self, she must uncover who did this to her and why (and if it can be reversed) before it happens again.

previously….

A timid young war widow, who awakens naked on a snowy roof at dawn with soldiers shooting at her, has to figure out who she is and what the hell happened to her last night. Fast.

All help gratefully received

David

**********

From: Carson Reeves

Title: She’s Got Claws

Genre: Horror/Thriller

Logline: A timid young war widow, who awakens naked on a snowy roof at dawn with soldiers shooting at her, has to figure out who she is and what the hell happened to her last night. Fast.

Analysis: Okay, you know with me, I’m always trying to simplify your ideas. You tend to go very in-depth, which is good in theory, but I think you would benefit from simplifying things down. Of your two loglines, the second one is better, as it creates a more urgent dramatic situation. But I would love to get the father connection in there. As soon as I read that, it made the scenario sound a lot more interesting. I don’t love the adjective “war widow.” Does that mean her soldier husband died? Or does it mean she’s also a soldier herself? It’s more interesting if she was a soldier herself. Either way, I would like to start the logline off, and the protag description off, a lot cleaner. Which leaves something like this…

New Logline: A were-lion, who awakens naked on a remote military black site, learns that she slaughtered five people the previous night and she’s being hunted by her bloodthirsty military commander father.

**********

From: David Laurie

Hey

thanks for this

War widow = husband died in Afghanistan. I’m not crazy about the term either.

Here’s how the story rolls out.

It’s a mystery and Holly peels back the layers to find the simple ugly truth.

So the logline KINDA has to hold a lot back, which is why I based it around the set up.

The REVEALS shift Holly’s understanding of what went down, of her father/family but mostly of HERSELF.

She’s not a soldier. She’s not much of anything. No kids. No job. Which is her realisation.

When her father, the General, shows up with Marines, she assumes he’s to blame for her transformation

Reveal #1 her husband PETER was not dead at all – but he is now – as of last night

Reveal #2 her soldier sister, IVY, is not in the Middle East, She’s been working on weaponizing the Afghan changeling DNA with Peter. Living on the black site – not one mile from Holly – for 2 years

reveal #3 The General had sponsored the program but Peter and ivy have gone wayyy off the reservation so he showed up to shut them down

reveal #4 last night Ivy kidnapped Holly and tortured her to force Peter to kill the General. Peter took the changeling DNA, went on the rampage and HE killed all the men in the night

reveal #5 Holly injected herself with the Changeling DNA to go after Peter and stop him killing her father.

reveal #6 Holly killer her own husband and no-one else

At least, until she woke up and the soldiers came after her

So, on awakening, the truth was: she had only killed one person and for a good/justifiable reason

Title: She’s Got Claws

Genre: Horror/Thriller

cool

Logline: A timid young war widow, who awakens naked on a snowy roof at dawn with soldiers shooting at her, has to figure out who she is and what the hell happened to her last night. Fast.

Analysis: Okay, you know with me, I’m always trying to simplify your ideas.

yep

You tend to go very in-depth, which is good in theory, but I think you would benefit from simplifying things down.

deffo for the logline

I feeeeeel like it’s a simple story.

But it’s a false narrative

It starts on a number of wrong assumptions and clarifies/builds to a final reveal

Of your two loglines, the second one is better, as it creates a more urgent dramatic situation.

yep

But I would love to get the father conneciton in there.

yep

As soon as I read that, it made the scenario sound a lot more interesting.

yep

that’s the thing

Holly is boring

Her military family is all horrible, one way or another – she is the, um, white sheep of the family.

and the story is her drilling down into her fuckedup family

I don’t love the adjective “war widow.”

same

Does that mean her soldier husband died?

yep

Or does it mean she’s also a soldier herself? It’s more interesting if she was a soldier herself.

I disagree

i think it’s more fun pitting the dowdy, dull civilian up against cops, Marines and mercenaries

only she has a secret advantage, being a “werewolf”

which she is not thrilled about

Either way, I would like to start the logline off, and the protag description off, a lot cleaner. Which leaves something like this…

New Logline:

A were-lion, who awakens

DO YOU THINK HUMAN AGAIN IS IMPLIED?

I WRESTLED WITH THIS

naked on a remote

GONNA SWITCH remote FOR ALASKAN

military black site, learns that she slaughtered five people the previous night

SHE THINKS THIS IS THE CASE

BUT IT WILL TURN OUT NOT TO BE

BUT THINKING IT MAKES IT A BIT EASIER WHEN SHE KILLS TEN MORE

and she’s being hunted by her bloodthirsty

HE’S MORE TERRIFYING EMOTIONLESS HARDASS THAN BLOODTHIRSTY

military commander father.

SO maybe

A were-lion, who awakens naked on an Alaskan black site, learns that she’s being hunted by her brutal military commander father, in connection with a string of corpses discovered last night.

BUT

for me that feels like Holly has the upper hand, being a werewolf. So that’s not good

This is why I wanted to start with the meek/timid/dowdy shizzle

A timid woman, who awakens naked on an Alaskan black site, learns that she’s being hunted by her brutal military commander father, after fifteen men were slaughtered last night.

so does that imply werelion?

I get the clean THIS IS A WEREWOLF WE ARE TALKING ABOUT opening

but the reality is in pitching this story to any exec, there’s no way it’s not preceded by THIS IS MY SPIN ON A WEREWOLF STORY

also the anatag gets 4 words

and the protag only 2

A timid widow, who awakens naked on an Alaskan black site, finds she’s being hunted by her brutal military commander father, after fifteen men were slaughtered last night.

THOUGHTS?

**********

From: Carson Reeves

Well, it comes down to: Do you want to tell the reader what the movie is about? Or do you KIND OF want to tell them what it’s about, but build the logline more around mystery? My experience is that it’s better to tell them what the movie is about.

**********

From: David Laurie

hi

Well, it comes down to: Do you want to tell the reader what the movie is about? Or do you KIND OF want to tell them what it’s about, but build the logline more around mystery?

that, as you can imagine, is 100% my instinct

the story is a mystery

but I feel there is plenty of (literal) meat on the bones at the outset

My experience is that it’s better to tell them what the movie is about.

I know, I know and I suspect you are right. It will open the logline up to more people getting it

what about?

A timid young widow awakens naked on an Alaskan black site to find she’s being hunted by her military commander father, who thinks she’s the creature who slaughtered fifteen men last night.

From: David Laurie

for me that last one builds nicely

but the implied question is

is she that creature

and

the answer, right off, is yeah, she probably is

and with a little thought, you get to she’ll probably be OK if she’s some kind of monster

**********

From: Carson Reeves

Everything and the kitchen sink version:

The reserved widow of a recently deceased soldier awakens naked on an Alaskan military black site where she is being hunted by her relentless officer father, who believes she’s responsible for the slaughter of fifteen men last night.

Edible version:

A startled woman awakens naked on an Alaskan military black site where she quickly learns she is being hunted by her high-ranking general father, who believes she’s responsible for the slaughter of fifteen soldiers last night.

**********

From: David Laurie

The reserved widow of a recently deceased soldier awakens naked on an Alaskan military black site where she is being hunted by her relentless officer father, who believes she’s responsible for the slaughter of fifteen men last night.

yep

Edible version:

as in high? (ho ho)

A startled

!

woman awakens naked on an Alaskan military black site where she quickly learns she is being hunted by her high-ranking general father, who believes she’s responsible for the slaughter of fifteen soldiers last night.

another problem is that the phrase ‘General father’ sounds weird so

A timid young widow awakens naked on an Alaskan military black site where she quickly learns she is being hunted by her high-ranking father, who believes she’s responsible for the slaughter of fifteen soldiers last night.

I think it’s either

A timid young widow awakens naked on a remote Alaskan black site, to find she’s being hunted by her high-ranking father, after fifteen soldiers were slaughtered last night

OR

A timid young widow awakens naked on a remote Alaskan black site, to find she’s being hunted by her high-ranking father, who thinks she’s the creature who slaughtered fifteen soldiers last night.

**********

Carson Reeves

I’m having issues with the word “timid” as it’s an adjective that sounds very small for a story with such high stakes (and high body count). ‘Timid’ is an adjective you would use in a comedy. That’s why I’m trying to change it.

I’m a little worried that with “Alaskan black site,” people aren’t going to know what you mean. That’s why I put “military” in there.

Thoughts?

**********

David Laurie

Deffo onboard with military

I put it back in too

And took out remote

Cos Alaska

Timid is accurate

And I hope IRONIC

A female sergeant wakes up and is accused of 15 murders…

Is not as cool as

The last person you’d ever suspect wakes up…

A timid young widow awakens naked on a remote Alaskan military black site, to find she’s being hunted by her high-ranking father, after fifteen soldiers were slaughtered last night

From: David Laurie

Also

You classed it as

Horror / Thriller

Which I think is accurate.

But I worry that, for a werewolf, it is a step too far away from Horror as a main genre.

I guess that is the bed I wrote for myself.

Btw, there’s no silver bullets etc

Instead it’s science based, DNA, CRISPR technology

**********

From: Carson Reeves

Okay, if you’re standing firm on “timid,” I will concede. :)

We need a better way to describe the father. “high ranking” doesn’t work. Can you give me his exact military title and his job outside of this movie? The wording of “After fifteen soldiers were slaughtered last night” feels a little too casual.

A timid young widow awakens naked on a remote Alaskan military black site to find that she’s being hunted by her high-ranking officer father after fifteen of his soldiers were slaughtered by a mysterious creature.

**********

From: David Laurie

Okay, if you’re standing firm on “timid,” I will concede. :)

Yay

We need a better way to describe the father. “high ranking” does’t work. Can you give me his exact military title and his job outside of this movie?

He’s a general

Based at the pentagon and charged with weapons development

The changeling DNA is being developed as a biotech weapon, supersoldiers type thing

Ivy, her sister was running the project but has gone nuts and is churning through “volunteers” and burning the bodies

The wording of “After fifteen soldiers were slaughtered last night” feels a little too casual.

Ok

The number needs to feel “significant”

A timid young widow awakens naked on a remote Alaskan military black site to find that she’s being hunted by her high-ranking officer father after fifteen of his soldiers were slaughtered by a mysterious creature.

See

I like that

But I can hear the message board pedants saying that the last bit is not directly linked to the first

Even tho, to my ears, it is

**********

From: Carson Reeves

Maybe we need to move some things around to make it sound smoother…

After waking up naked and confused on a secluded Alaskan military site, a reticent young widow discovers she’s the prey of her high-ranking officer father, who’s pursuing her following the slaughter of fifteen soldiers by a mysterious creature.

***********

From: David Laurie

hmmmm

I thinnnnk that’s a bit unwieldy, maybe a clause too many

I trimmed the one below to

A timid young widow awakens naked on an Alaskan military black site to find she’s being hunted by her father, a DC General, after fifteen of his soldiers were slaughtered by a mysterious creature.

I think the a Pentagon General or a DC General is less bumpy and more organic

plus it has:

ironic underdog protag

overmatching antag

violent monster mystery

hunted which implies a call to action

From: David Laurie

his flows a little better

A timid young widow awakens naked on a military black site in Alaska to find she’s being hunted by her father, a DC General, following the slaughter of fifteen soldiers by a mysterious creature.

**********

From: Carson Reeves

We’re getting close. What I’m trying to do is link the first section with the “mysterious creature” so it doesn’t sound like it’s coming out of nowhere. If she’s just naked, does that tell us enough? That’s why I was going with, “naked and confused,” to imply that something has just happened to her and she’s scared and doesn’t know what it is. But I don’t like having two words there since it makes it longer.

The only other thing that bothers me is the dad’s occupation. It’s the clunkiest part. I wish we had the perfect descriptor there.

A timid young widow awakens naked on an Alaskan military black site to find she’s being hunted by her father, a decorated army general, after fifteen of his soldiers were slaughtered by a mysterious creature.

From: Carson Reeves

Okay, let’s give it a day. I find that it’s easier to find the path when you’ve had some time away from the logline. But we’re definitely closer.

**********

From: David Laurie

OK agreed

I’ll let it sit

did you see the one i sent a minute ago

it flows better

A timid young widow awakens naked on a military black site in Alaska to find she’s being hunted by her father, a DC General, following the slaughter of fifteen soldiers by a mysterious creature.

**********

From: Carson Reeves

I think it’s a little better.

**********

From: David Laurie

re your points below

A timid young widow awakens naked and confused on a military black site in Alaska to find herself being hunted by her father, a DC General, after fifteen of his soldiers were slaughtered by a mysterious creature.

I like find herself for the same reason I like awakens

i think confused is implied.

who’s NOT confused by waking up naked in snow on a secret base?

A timid young widow awakens naked on a military black site in Alaska to find herself hunted by her father, a DC General, after fifteen of his soldiers were slaughtered by a mysterious creature.

i like

awakens naked

after fifteen

and I especially like

fifteen of his soldiers

cos it seems like he cares more about his job than her

which he does

From: David Laurie

A timid young widow awakens naked on a military black site in Alaska to find herself hunted by her father, a DC General, after fifteen of his soldiers were torn apart by a mysterious creature.

torn apart is more ANIMAL

From: David Laurie

military

DC General

soldiers

seems like overkill

I’d be inclined to use MEN instead of soldiers but that is a bit sexist

so if we keep soldiers, we can lose military

**********

From: Carson Reeves

I think I like “slaughtered” more than “torn apart.” It sounds more visceral and violent. But if you love “torn apart,” it’s fine. I don’t like “DC General.” Every time I read it, I wonder exactly what it means. Like Washington DC? Then why is he in Alaska? I’m sure it makes sense but you can’t take chances in these loglines. Everything has to be as clean as a surgery room.

A timid young widow awakens naked on a military black site in Alaska to find herself hunted by her father, a ruthless general, after fifteen of his soldiers were torn apart by a mysterious creature.

**********

From: David Laurie

I think I like “slaughtered” more than “torn apart.” It sounds more visceral and violent.

Her killings are very visceral

She tears soldiers heads off more than once

I soldiers being slaughtered could be achieved with an AR-15

Torn apart sounds more claws and teeth to me

But if you love “torn apart,” it’s fine. I don’t like “DC General.” Every time I read it, I wonder exactly what it means. Like Washington DC? Then why is he in Alaska? I’m sure it makes sense

I agree

I also am not keen on the commas around it, fucking up the flow

but you can’t take chances in these loglines. Everything has to be as clean as a surgery room.

I hear you

A timid young widow awakens naked on a military black site in Alaska to find herself hunted by her father, a ruthless general, after fifteen of his soldiers were torn apart by a mysterious creature.

I like this.

It’s accurate and it hits the tone.

it’s 35 words which is on the edge of acceptable; but I think it has maybe 3 too many polysyllabic words

which fu**s the flow a bit

the closer it is to a haiku the better, right?

I also don’t really like mysterious in loglines

like: this is the time to tell us the mystery

A timid young widow awakens naked on a black site in Alaska to find herself hunted by her father, a ruthless general, after his men were torn apart by an unseen creature.

thoughts

From: David Laurie

Good morning/evening btw

On an Alaskan black site, a timid young widow awakens naked and finds she’s being hunted by her father, a ruthless general, after his men were torn apart by an unseen creature.

**********

From: Carson Reeves

I definitely don’t like the re-shaped version of the logline. Let’s stick with what we’ve got. I think the below is very good. Only quibble, like you, is “mysterious.” I think it works but could probably be better. “Unseen” is too weak a word for this scenario.

A timid young widow awakens naked on a military black site in Alaska to find herself hunted by her father, a ruthless general, after fifteen of his soldiers were torn apart by a mysterious creature.

maybe…

A timid young widow awakens naked on a military black site in Alaska to find herself hunted by her father, a ruthless general, after fifteen of his soldiers were torn apart by a nightmarish creature.

**********

From: David Laurie

I definitely don’t like the re-shaping version of the logline. Let’s stick with what we’ve got.

ok

think you missed one of my emails just now.

this loses a bunch of syllables but stays true

I think ‘she’s being hunted’ is punchier/more active

I quite like unseen, and in the story, the general has not seen what his daughter becomes.

Anyone who sees her, dies

(until she makes friends with a cop, whom she spares yadda yadda romance budding)

A timid young widow awakens naked on a black site in Alaska to find she’s being hunted by her father, a ruthless general, after his men were torn apart by an unseen creature.

A timid young widow awakens naked on a black site in Alaska to find she’s being hunted by her father, a ruthless general, after his men were ripped apart by an unseen creature.

A timid young widow awakens naked on a black site in Alaska to find herself hunted by her father, a ruthless general, after his men were torn apart by a ferocious creature.

**********

From: Carson Reeves

I would put “fifteen” back in there. And I would put “soldiers” back in there. Both give the situation more weight. So…

A timid young widow awakens naked on a black site in Alaska to find herself hunted by her father, a ruthless general, after fifteen of his soldiers were torn apart by a ferocious creature.

**********

From: David Laurie

do you not think finds she’s being hunted is better than finds herself hunted

*********

From: Carson Reeves

how would “finds herself hunted” look in actual practice?

**********

From: David Laurie

fair warning, I am a bit of a grammar Nazi. My mum was an English teacher

so

I thinnnnnk

finds she’s being hunted means the hunt is under way, which it is

and

finds herself hunted is flappy enough to mean the hunt might start later in the story

*********

From: Carson Reeves

Yeah, but you also have to take into consideration how it reads and sounds within the context of the logline. It sounds better, in my opinion. And when I hear “finds herself hunted,” I think the hunt is happening right now.

*********

From: David Laurie

OK

might be just me being fussy

I concede it flows better

So

A timid young widow awakens naked on a black site in Alaska to find herself hunted by her father, a ruthless general, after fifteen of his soldiers were torn apart by a ferocious creature

it’s definitely one of those, this is the set up not the story loglines but the setup IS the story and the whole movie is a hunt, one way or another

I think saying his men, rather than soldiers, implies a sort of paternal concern for the chewed-up guys, which is relevant

annnnnd it shortens/smoothens the last clause

but

it takes the original three army terms down to one

so

maybe

A timid young widow awakens naked on a military black site in Alaska to find herself hunted by her father, a ruthless general, after fifteen of his men were torn apart by a ferocious creature.

I am into this version. You?

**********

From: Carson Reeves

Yeah, I liked the way you phrased “men” in this last one. It works for me. I think we’ve got it. :)

**********

From: David Laurie

yeah

I agree

thanks man

pleasure doing business

*****END OF EXCHANGE*****

And there you have it! Here are the old and new loglines!

Old: A timid young war widow, who awakens naked on a snowy roof at dawn with soldiers shooting at her, has to figure out who she is and what the hell happened to her last night. Fast.

New: A timid young widow awakens naked on a military black site in Alaska to find herself hunted by her father, a ruthless general, after fifteen of his men were torn apart by a ferocious creature.

Genre: True Story

Premise: To get the performance he demands for “The Shining”, despotic director Stanley Kubrick emotionally tortures relative newbie Shelley Duvall. When she refuses to play the victim any longer, Shelley uncovers dark secrets that may completely destroy the film — and her sanity.

About: This was one of our entries in the Halloween Logline Showdown. David Kessler has been a longtime Scriptshadow reader and powered his script, Minimata, forward over the years, getting Johnny Depp attached. The movie, about the devastating effects of mercury poisoning, has a 92% audience score on Rotten Tomatoes.

Writer: Asher Farkas and David K. Kessler

Details: 113 pages

I’m still experiencing some PTSD from the key duplication fiasco which is why this review is appearing on November 1st instead of October 31st. I had convinced myself that Halloween was on Wednesday. Maybe it’s a good idea for me to not drive today. Clearly, I don’t know which way is up and which way is down.

Ironically, this is the best state of mind to be in while reading today’s script, seeing as our protagonist is being mind-f**ed by the greatest director in cinema history. Well, according to Stanley Kubrick, that is. The Kubster always had a little ego on him. Are you ready for this post-Halloween ride? Grab your set of backup keys and let’s find out.

It’s the 70s and Actress Shelley Duvall (awkwardly tall, crooked teeth) has been steadily moving up the actor food chain. Her rise is a true underdog story. She had no desire to be an actress and was randomly discovered by Robert Altman. As a result, she doesn’t train. She acts by instinct. That’s exactly why Stanley Kubrick wants her for his Stephen King adaptation of The Shining.

Shelley will have to leave boyfriend, singer Paul Simon, to go shoot in England for 4 months. Of course, that’s an optimistic estimation of the shoot’s length. With Kubrick, you have no idea how long a shoot is going to last.

When Shelley arrives on set, the intimidating Mr. Kubrick tells her that he likes to use a lot of takes and if she isn’t cool with that, she can be replaced. He also tells her that he chose her because he needed someone who could easily be broken. Confused by that comment, Shelley heads to her room.

It isn’t long before Jack Nicholson shows up. Jack looks like an old pro. Whereas everyone else is walking on eggshells around Kubrick, Nicholson rolls with it, seemingly unaffected by anything he says. Even Kubrick seems a little put off by this – that someone wouldn’t cower at his feet every time he walked in a room.

Immediately, strange things start happening to Shelley. After taking a shower, she finds a new script on her bed, despite her room having been locked. She says hi to Margaret, Kubrick’s secretary, who she met back in New York. But Margaret insists that she’s never met Shelley in her life. She starts getting phone calls in her room with no one on the other end. She tries to watch TV but, somehow, there are only horror movies playing. None of the other channels work.

On set, Kubrick puts her through the wringer. When she hasn’t memorized her lines (which he just sent changes to earlier in the day) he announces to the entire crew that they’re done for the day because Shelley couldn’t memorize her lines, embarrassing her. Kubrick brings the boy actor, Danny, in with his fake make-up bruises and throws them in Shelley’s face to get her to be more emotive during crucial scenes.

But the worst thing they do is they get Shelley a dog to cheer her up, only to then facilitate the dog “escaping” and then being brutally killed. Shelley witnesses the aftermath of the death and becomes inconsolable. She requests time off but Kubrick insists she keep working and thrusts her right back into a scene just hours later.

Then, of course, you’ve got the takes. We’re not talking 30 takes. We’re not talking 60. Or 90. We’re talking some time enduring over 100 takes! It is insanity. And Kubrick seems to revel in it. But will it break Shelley to the point where she’ll no longer be able to work? Or is there a light at the end of this tunnel? Great art must be suffered for, argues Kubrick. That saying will be put to the test.

Yesterday we talked about coming up with a movie idea and then deciding which direction to take it in. Do you take a movie about a group of people coming into a bunch of money in a goofy fun direction? Or a dark comedic direction?

Well, with today’s script, we actually get to see what it looks like when a concept is taken in two different directions. That’s because this idea was also explored by Colin Bannon in his Black List script, “Let’s Go Again.”

Bannon’s interpretation was different in a couple of ways. It threw us into the fire immediately. And it kept pounding us with the craziness relentlessly. It was the kind of execution that never gave you time to breathe. Kessler and Farkas’s version is more of a slow-build. It exists just as much in the spaces between the scenario as it does the scenario itself.

There are plenty of slow moments here. For example, when Shelley goes back to her room to prepare for the next day, Kessler and Farkas will stay there with her. Sit in her frustration.

I always feel like the scariest moments happen in the build up which is why I was appreciating this version of the idea so much. Especially when you’re talking about someone going crazy. The entertainment comes from her and us wondering if she’s really going crazy. When Shelley comes out of her shower to find the latest draft of the script on her bed and her hotel door still locked from the inside, we’re freaking out because it’s all happening in real time.

I just remember with Bannon’s script the insanity was being beaten over our head twenty times a scene. There was never a time in that script where we could breathe.

Another advantage of slow build-ups is they create an evolution in the story. We start slow, then get medium, and eventually ramp up to fast. So each section of the screenplay feels different. Whereas if you start off fast then stay fast the whole time, the entire movie feels the same. Most scripts need variation. People don’t like when you stay in one gear for an entire 2 hours, no matter what gear it is.

So then the answer is: “always take your time,” right? Not necessarily. Movies do favor urgency. Plots tend to work best when they move fast. So starting your movie in media res is a perfectly reasonable creative choice. Also, studios and audiences tend to like faster-moving stories. It’s less work for them.

Here’s something that might help you decide which is best for you. The better the writer you are, the more you can take your time. Good writers understand how to keep things entertaining when the story is moving slowly. Average writers fall apart when they try and do this. So, if you’re someone who doesn’t think of yourself as a master of suspense or a wordsmith, it may be best if you keep things moving quickly, as it’s easier to camouflage your writing deficiencies.

Maybe that’s why I enjoyed this script less when it hit its fast-paced second half. There’s something about descending into insanity that doesn’t jibe with the way I like my entertainment. I like my screenplays with structure. I like to feel that the writer has a plan and that we’re moving somewhere with purpose. Descending into insanity doesn’t work well with that approach. And I’m not saying it’s wrong. I’m just saying I personally don’t like it. At a certain point you’re just going nuts over and over and nothing’s really changing.

Another quibble I had was that Farkas and Kessler are cheating. They’re sneakily straddling both sides of the fence. They want the intellectual property advantages of referencing the real people and real event that make up this story, while also making things up when they wanted to. I’m guessing that massacring a dog to get a better performance out of Shelley Duvall didn’t happen.

It’s not a huge deal but one of the cool parts of watching a movie like this is you can say, “Wow, I can’t believe that really happened. That’s nuts!” You can’t do that here. You have to concede that that heart-stopping scene may have happened… or may have been totally made up. To me, that’s a bit of a cheat. I think they either should’ve stuck to the truth or did what Bannon did (invented fake characters then used the Kubrick-Duvall situation as inspiration).

Of course, the movie goes full-on super-psycho in its last 20 pages, letting us know this is complete fiction. And I probably would’ve enjoyed it more if I was right there with all the Shining references. I can tell David and his writing partner have seen the movie 50+ times. I’ve only seen it twice so and both viewings were a long time ago. So I didn’t get the references that I’m sure Shining super-fans will love. For this and the reasons I stated above, Scaring Shelley didn’t quite make it to “worth the read” territory for me. But I’ll tell you what. If you’re a Shining fan, you’ll probably love this.

Script link: Scaring Shelley

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Keep us in the loop. In a movie like this where it’s taking place over a series of months (that’s how long the shoot is), it’s a good idea to tell us WHERE WE ARE IN THE SHOOT. For example, every once in a while, include a title card that says, “Day 45,” which is what Kessler does here. Because, if you don’t do that, you have no idea where the reader thinks they are. You might be on day 90 of the shoot but the reader thinks you’re on day 10. So you guys are experiencing two different films. I just read a consult script where this exact issue occurred. It was a time loop script and I thought we’d looped 50 times. After talking to the writer, it turns out we’d looped 2000 times. So I said to him, “You have to tell us that (or at least strongly hint at it). You can’t just assume we’ll know.”

Genre: Comedy

Premise: Ten years after a group of girlfriends bet on which of them would be the last to get married, their adult lives and relationships are completely upended when they discover the $80 they drunkenly invested in Bitcoin

is now worth $5.2 million.

About: We’ve definitely got the best name of all the Black List writers with this script: Daisygreen Stenhouse. Stenhouse writes with Liv Auerbach. Both are new enough to professional screenwriting as this is their first notable script, which finished on last year’s Black List with 6 votes.

Writers: Liv Auerbach & Daisygreen Stenhouse

Details: 97 pages

Anna Kendrick for Skyler?

Anna Kendrick for Skyler?

You’ll have to excuse me if I sound a little off-kilter today. About a year ago I lost the back up set of my keys and unfortunately, the remaining keys all say “do not duplicate” on them so I’ve spent the last year putting off getting a new back up set since I knew it would be such a hassle.

Then yesterday somebody told me that the whole “do not duplicate” thing is not legally binding. You can go to any hardware store and they’ll ignore it, copying the key for you! When the HEEEEEELLLL did this happen?? I feel like my whole life has been a lie. I apologize to the writers of this script as this world-changing view made it hard to concentrate on any other matter than not duplicateabitable keys.

22 year old Skyler, an aspiring sports agent, is a Duke student who makes a bet with her seven best friends – the main ones being Willa, a lesbian hopeless romantic, Frankie, a super slut, Nisha, a “posh narcissist,” Jules, the “no filter” girl, and Poppy the hippy – that whoever gets married last wins the pot of money.

They’re all going to put in 10 bucks. For some reason, there’s a bracket involved, like a tournament. But it doesn’t really make sense since nobody is actually playing against each other. It’s whoever marries last wins. So that was a little confusing. But anyway, at the last second, they decide to throw the pot of money into this new thing called “bitcoin.”

Cut to 10 or so years later and Skyler, who’s frustrated about still being an agent’s assistant, goes to check the bitcoin pot only to find out it’s now worth 5 million dollars!! She tells her friends and insists that they stick to the competition agreement. No sharing. The only two people left besides Skyler are Willa, who’s way too passive on the dating scene, and Frankie, who has only ever said she’ll marry Tony Hawk.

Thus begins Skyler’s secret plan to speed up Willa’s dating life and somehow convince Tony Hawk, who’s already married, to marry her friend. She figures if she can get this money, she can quit her bigoted agency and start her own company. Meanwhile, Frankie starts secretly hanging out with Skyler’s fiancé, Mark, encouraging him to pop the question to Skyler as soon as possible. Who will win out and force the other to marry first? That is the 5 million dollar question!

This script opens up an interesting discussion about what to do when you’re faced with two different paths for your chosen concept. Because one version of this concept is a fun silly Hollywood comedy. But that’s also the less interesting version of the concept.

The more interesting variation is the dark comedy version where people get nasty when they realize how much money is on the line. Maybe they even start killing each other. Unfortunately, that version is a lot less marketable. Look no further than the difference between Bridesmaids and Bachelorette. Both movies covered bridesmaids in a comedic fashion. But while one was a megahit that became a part of popular culture, the other is nearly forgotten.

However, what you’ll note is that the writer of the dark comedy version of the idea, Leslye Headland, went on to have a cool career that involved making shows like Russian Doll. Her darker comedic voice made her a “cool kid on the block.” And the thing about becoming a Hollywood cool kid is that you always get invited back to the cool kids’ table where you can pitch your latest cool project.

The people who write movies like The Man From Toronto or Me Time don’t get that courtesy. They’re actually some of Hollywood’s most discriminated-against writers (is “comedyist” a thing?) because broad comedy is thought to be the hackiest of all the genres. Then again, you don’t really care about that if you’re clearing 750,000 dollar checks.

In the end, you have to decide what is more organic to you. What are you better at? Also, what do you want to be? Do you want to make fluff yet buy a house in Hancock Park? Michael Bay once famously said, “I make movies so I can buy Ferraris.” If you want to be that kind of screenwriter, I have NO QUALMS with that. But you have to be willing to sacrifice some artistic integrity and be okay with a few sneers when you walk past the cool kids table.

Okay, about the script.

It’s working under a problematic structure – namely, it’s being dictated by a negative goal, and negative goals are hard to pull off. What’s the difference between a negative and positive goal? Well, a positive goal would be that all these girls are trying to get married as fast as possible because the first person who gets married wins the money.

That’s not this movie, though.

Each person is trying to AVOID getting married. That’s a negative goal. Now, why would that be a writing problem? Because it’s easy to not do something. You just don’t do it! It’s simply not as compelling as doing something. Also, negative goals are really bad at pushing the plot forward.

Today’s writers try to circumvent this with some sleight of hand. The negative goal is turned into a positive goal by having Skyler try and get her unmarried friends married. So now Skyler technically has a positive goal that makes her active. But it still doesn’t solve the issue that Skyler, herself, doesn’t need to get married. So then where’s the drama? Where’s the suspense? I suppose that by Skyler being active and getting her friends married, she receives the money faster. But I don’t know if I care about that. I mean am I really going to be in the theater, on the edge of my seat, saying, “Oh man! I really want Skyler to win this money as soon as possible!”

You know how when a writer uses a double negative in a sentence, we, the reader, have that hiccup while reading it? It takes you an extra second to understand the meaning of the sentence. That’s this script in a nutshell. You constantly have to remind yourself why people are doing what they’re doing because it’s all reversed. It’s not a clear easy-to-understand goal.

Whenever you have goal issues, you’ll have stakes and urgency issues. Cause your goal dictates your stakes and urgency. There is zero urgency here. The only urgency is Skyler’s impatience. It doesn’t matter if she gets the money today or four years from now, she’s still going to get it.

Even still, the objective we’re after takes so long to complete (a wedding that officially eliminates a contestant) that we don’t feel any tension from the situation. Skyler is trying to find a girlfriend for Willa. Let’s she say she does. Now we have to wait a year for them to get married and we can cross Willa off the list? That’s not how movies work. Movies work in tight timeframes. We’re talking weeks. We’re talking days. That’s the timeframe you want to be working with. Especially in comedy, where things need to move fast.

The writers do display some creativity. For example, the movie starts at a Duke basketball game and the announcers of the game break the 3rd-and-a-half wall and start commentating on our group of girls instead. That then becomes a running theme throughout the movie where sports announcers will narrate the latest developments with the girls.

I like it when writers think outside the box so I appreciate this. But, at the time same, when I see this sort of thing, I tend to think that the writers are trying too hard. Sort of like, “Look at me. I came up with this clever thing. I’m so clever.” Unless it feels soooooo organically ingrained in the writing, I can’t help but label stuff like this “try hard.”

One of these days, I’m going to write an article about where the line is when it comes to acceptable sloppiness in comedy. I think today’s concept is too overbearing and not believable enough. I mean, let’s be honest. Wouldn’t these girls just split the money? They’re all friends. None of them are greedy. So for them to go along with this ancient bet thing feels forced. And if you don’t believe in that premise, nothing in the movie will work, since all the dramatic tension is dependent on you caring about the bet.

But is that my fault? This is comedy. Shouldn’t I loosen my grip a little bit? Why am I being so anal about every part of the script being airtight? Would a family really drive their dead grandma around on the top of their car as they did in National Lampoon’s Vacation? Probably not. And yet that movie is a classic.

But, for me, there’s way more loose than tight here. I’m fine with a little sloppiness in comedies. It can actually help the comedy at times. But if I don’t even believe that what’s happening would happen, it’s hard for me to invest emotionally. And if I’m not invested emotionally, it’s hard for me to laugh. I’ll chuckle. I’ll have a few of those surface-level laughs. But for those deep uncontrollable laughs, the screws have to be way tighter than they are here.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: The one thing this script gets right is that the money represents something. Money is always a far more effective tool in a screenplay when it represents something important to a character. In this case, we establish Skyler’s desire to get promoted to an agent. That way, when the windfall of money enters the equation, she becomes obsessive about it, because it means she can finally quit her job and start her own agency, something she’s dreamed of since she was a kid.

So much good in this month’s newsletter. So much good! I’m pretty sure I discovered the elusive sci-fi project that Tarantino has been looking for. I’ve got a script review that’s going to help everyone here who becomes a 7-figure studio screenwriter in the future. I announce next month’s Logline Showdown theme. I compare this year’s two big Oscar hopefuls. Which one is better!? I talk about the secret to being able to write long screenplays (and all screenplays, for that matter). I’ve got a bonus question in this month’s trivia question to make a script consult even cheaper. And I ask if Michael Mann is having a Mannessance.

Unfortunately, being forced to work all weekend on my newsletter has wiped me out. So there will not be a Monday post. Therefore, I’ll talk about Five Nights at Freddy’s right now! The movie made 78 million dollars – something nobody expected. But the bigger question is: is there a conspiracy to take the movie down? The film got an A- Cinemascore, a near impossibility for horror films. Yet it’s only getting a 25% on Rotten Tomatoes. Something is fishy here. As far as all the money the film’s making, though, I think it’s pretty clear. This movie has a HUGE built-in video game audience. The orignal video game was always cinematic so this made sense. It does put the spotlight on video game adaptations because now we have an official trend. Last of Us. Super Mario. Five Nights at Freddies. They finally figured the video game adaptation thing out. It only took them 25 years. So expect a lot more of these in the future!

If you want to get on my newsletter list, e-mail me at Carsonreeves1@gmail.com.