Has today’s writer conquered one of Hollywood’s screenwriting chupacabras? Written “the next Goonies?”

Genre: Ghost/Adventure

Premise: A Wisconsin high school girl teams up with her friends to look for a ghost ship she believes is connected to her mother’s disappearance.

About: This script finished with 6 votes on last year’s Black List. So far the writer, Nicole Ramberg, has made a few short films. She is repped by Bellevue. She graduated from Northwestern as well as the NBCUniversal Page Program. She won the 2020 ScreenCraft Action and Adventure category. She is a fellow Chicago suburbian. So I hope this script is good!

Writer: Nicole Ramberg

Details: 120 pages

What separates a top 10 Black List script from a bottom 10 Black List script? Is there any difference between the two? We’re going to try and answer that question in today’s review.

The year is 1993 and 15 year-old Riley Halbeck is living in the American equivalent of hell, aka, Wisconsin (I can say that because I went to college there). Riley and her young sister, Emma, live with their aunt, Annie, because several years ago, their mother disappeared.

Riley, who’s best friends with chatty Ash and sweet Wyatt, has heard rumors that multiple disappearances, not just her mother’s, are tied to the mysterious La Salle Island, which is just off the coast. It is said that near La Salle, people have seen a ghost ship floating around.

Wyatt convinces his pals to head out to that very island on Halloween and, when they get there, they find a girl named Danielle Keller unconscious on the beach. Danielle disappeared eight years ago! And she hasn’t aged a day!

Hoping for a break in her missing mother’s case, Riley encourages Danielle to tell the cops everything she knows. Instead, Danielle says she ran away, ran out of money, and came back. It appears that Danielle would rather lie than have everyone call her a kook. It usually doesn’t go over well when you tell people you were abducted by a ghost ship.

Through the process of deduction, Riley realizes that whoever is manning the ghost ship is looking for a treasure on La Salle Island. If they can find that treasure first, they can lure in the ghost, and, in the process, find Riley’s mom. So the band heads back out to La Salle. But not everything goes as planned.

So, let’s answer that question. What separates the scripts at the top of the Black List from the ones at the bottom? In my experience, top level scripts tend to take more creative chances, tend to be darker, and tend to have more interesting voices. Whereas scripts at the bottom of the pack are often safer, more formulaic, and less likely to offend. They’re sanitized.

There’s some irony to this in that Hollywood likes making more of those bottom level scripts than the top ones. It’s the conundrum all screenwriters face when they put pen to paper. They can impress the young cool assistant crowd or they can impress the people who actually make movies.

But formulaic screenplays have their own set of challenges, namely that it’s incredibly hard to write a sanitized script that’s memorable. The Goonies is a great example of how to achieve that feat. It’s such a fun creative adventure that it doesn’t bother us that it’s so formulaic.

Craigshaven never reaches that level of creativity, unfortunately. The characters are dialed back so as to be ultra safe and impossible to dislike. And while that *seems* like the right thing to do, it’s the fastest way to writing bland characters.

I realize that when you watch Goonies today, there are some parts of it that are offensive. Watching the friends make their fat friend, Chunk, do an embarrassing “fat boy” dance would never make it into a 2023 movie theater. But, at the same time, that lack of fear to offend is what makes the character (and the friendship) more honest and memorable. Kids really did that sort of thing to their friends. And you know what? They still do. Cause kids are kids and they don’t know any better.

So if you erase all of that truth and just have everyone be perfect and inoffensive, I guarantee you, you’ll write boring characters. You would think that each friend in this story has never done a single bad thing in their life. They’re perfect little people. I can’t stress this enough. If your characters have no faults, they are uninteresting.

I’m not saying you have to have a “Chunk dance” in your script to make it good. But you have to figure out the 2023 version of what kids would really do to each other and give us some of that. Because without authenticity, you have an idealized version of the world. But guess what? The world is imperfect.

Another, more obvious, issue with this script is that it doesn’t have a villain! That’s what Goonies was famous for! It’s villains. The scary-looking guy. The mother with her criminal kids. The lack of any villains tells me the writer is scared to do anything hurtful to her characters. What have I told you about this? NEVER PROTECT YOUR CHARACTERS. Do the opposite! Put them through the wringer! Make their lives miserable.

Here’s the thing with screenwriting. When we come up with a script idea, we always have one major thing we want to focus on in the script. If you’re writing “Barbie” for example, maybe you’re obsessed with Barbie Land and really wanting to make that great.

But, in the process of focusing so much on Barbie Land, you may not care enough about the plot. You may not care enough about the message of the film. You may not put a ton of effort into Ken. And if you make that mistake, you don’t create an entire movie. You only create part of a movie. If Greta Gerwig would’ve done that, she would’ve missed out on creating the most iconic character of 2023 – Ken.

In Craigshaven, I see a writer hyper-focused on this boat mystery. By the way, you can always tell when a writer likes one element of their story above all others because whenever that element arrives, the writer spends way more time describing it. You can feel a change in their enthusiasm when it’s around.

But in being so hyper-focused on this ghost ship plotline, everything else falls by the wayside. Not just the characters but the plot. It’s too standard and basic. With screenwriting, you have to do it all. Or you at least have to try. From the concept to the voice to the characters to the storytelling to the dialogue to the relationships to the plot to the structure. You can’t half-ass any of those if you want to write a great script. You can half-ass some of them if you want to write an okay script. But I’m guessing you want more.

I do find something marketable about this concept, the writing is easy to read, and I thought the relationship between Riley and her aunt had a nice arc. It just didn’t push the envelope enough for me. I needed at least one area where it pushed the envelope. It’s hard for me to get on board a script where everything is written so safely.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: You need balance in a screenplay. If every character is sweet as candy, your reader’s going to get sick. You need to balance that out with some nasty characters.

Genre: Action/Thriller

Premise: A man wakes up in a hospital, no memory of who he is, with a bullet lodged in his head. Over the next 48 hours, he learns of his ties to a nefarious pharmaceutical company and the billionaire owner who wants him dead.

About: This is an older spec script that sold for $300k against $700k to Universal. It was purchased through Davis Entertainment, which is the same outfit that made the Predator movies (more recently, Davis has produced Game Night and Jungle Cruise). Half the writing team, Phoebe Dorin, has carved out a very successful acting career.

Writers: Christian Stoianovich & Phoebe Dorin

Details: 1994 draft

Will Poulter for Decker?

Will Poulter for Decker?

No Taylor Swift jabs today, I promise.

Instead, we’re going back to a time when Swiftie fans didn’t exist. It was a darker time. It was a grungier time. But if you were a screenwriter, it was a wonderful time. Cause Hollywood was buying everything with a brad attached. You may not know this. But screenwriter Lachlan Perry once sold a napkin with the words “Fade In” on the front, and three words inside, “Under Water Lion,” for 2.5 million dollars.

I totally made that up. But the fact that you almost believed me shows just how crazy those 90s were. Now let’s find out if “Bulletproof” warranted a sale.

We meet a mystery man as he’s running down a subway tunnel, chased by two men with guns. Our poor mystery man gets shot in the forehead. Normally, this is a death sentence. But, for some reason, our runner only passes out.

He wakes up 8 days later in the hospital, where he’s told that the bullet lodged in his head nearly killed him. In fact, if it had hit just a millimeter more in either direction, he’d be a goner. So he should feel lucky that he only has amnesia.

A cute doctor who specializes in amnesia, Kelly Chapman, comes to check him out. She gives him the typical “movie amnesia” spiel (“Memory is weird. Sometimes it comes back right away. Other times it takes a while) and informs him he should stay at the hospital as long as possible.

But the doctors let our mystery man go and that’s when he runs into Yuri Volkov, who tries to snuff him out in the elevator. Our bullet maestro somehow gets away and runs into Chapman in the parking lot. He unofficially takes her hostage, forcing her to drive him to safety.

After following a few leads, Bullet Man learns his name – Sam Decker. Decker realizes that he’s a scientist who worked for a gigantic pharmaceutical company called “Biotek.” It was there where he created the first ever medical male contraceptive. Aka, GOLDMINE.

For reasons we don’t know yet, he’d tried to sneak his research out of the lab, which is why everyone wants him dead. Did Decker know that his research was faulty and would kill millions? My guess is yes. But there’s one last twist to Decker’s research. It’s a twist that would make every act of sex an act of murder.

Something I often run into is flowery prose. What you have to understand about flowery prose is that when you start off as a writer, you think it’s more important than it actually is. So you put a lot of emphasis on. I’ll give you an example. Here’s a paragraph from early in the script.

Shadows scar the cobblestone driveway to the dilapidated hospital. White helmeted SOLDIERS, in a convoy of Jeeps roar past, belching black oily plumes of exhaust. A mongrel DOG pants in the doorway next to walnut-faced MEN playing dominoes. A legless MAN on a cart wheels past.

There’s a difference between trying to prove you’re a good writer and using your description to paint a picture. The line is thin but if you’re on the wrong side of it, readers will write you off.

It’s admittedly confusing because you do want your writing to appear strong. You don’t want to just write nouns, verbs and five-word sentences. But if your sole purpose for writing a sentence is to impress the reader, you’ve already got one foot in the proverbial grave. You should be writing paragraphs that do one thing and one thing only: serve your story.

And the point of description is to mimic, as best as you can, what the viewer is going to see onscreen.

Now, with this except above, you get a little bit of both so let’s go through it. “Shadows scar the cobblestone driveway to the dilapidated hospital.” This is a try-hard line. It’s the exact type of prose you don’t want to use. The more like poetry your lines sound, the less you want to use them. If you want to write poetry, go write poetry. This is a completely different medium.

“White helmeted SOLDIERS, in a convoy of Jeeps roar past, belching black oily plumes of exhaust.” This sentence is what you want in the first half and what you don’t want in the second. “White helmeted SOLDIERS” puts a relevant image in my head, as does a convoy of Jeeps roaring past. I feel like I’m watching a movie now.

But “black oily plumes of exhaust” is a try-hard description. I’m not going to stop reading if I see this. But if the writer has purple prosing me on every page and then I get another line of purple prose like this, I’m officially annoyed.

The description that really frustrates me, though, is “in the doorway next to walnut-faced MEN.” I don’t know what this means. A walnut-faced man? I’m literally imagining men with walnuts for heads. Is that what you want me, as a writer, to imagine? I would hope not.

You’re overthinking things. Use your description to describe, not to impress. Cause any time you’re *trying* to impress – I’m talking about in life, not just in writing – you’re usually doing the opposite.

Here’s an excerpt from the screenplay, “Seven,” by Andrew Kevin Walker. It takes place early in the story, with Somerset riding a train back to the city.

The train is almost full, moving slower. Somerset has his suitcase on the aisle seat beside him. He holds a hardcover book unopened on his lap. He still stares out the window, but his face is tense. The train is passing an ugly, swampy field. The sun has gone under.

Though it seems impossible it ever could have gotten there, a car’s burnt-out skeleton sits rusting in the bracken. A little further on, two dogs are fighting, circling, attacking, their coats matted with blood.

Note the clear imagery in the description. An almost full train. Moving slowly. His suitcase on an aisle seat. Hardcover book on his lap. A tense look on his face. An ugly swampy field. The sun has gone down. A burnt-out skeleton of a car in a field. Two dogs fighting nearby.

These are all things that we can clearly visualize. And if we’re visualizing them, it simulates the act of watching the movie in the theater. The only line I have a problem with is, “The sun has gone under.” We sometimes do this as screenwriters – write lines that are too sparse. But you probably needed one extra detail for this sentence: “The sun has descended below the horizon.”

Okay, onto the story itself. Was it any good?

Funny you ask. Something occurred to me as I was reading this script. It was sold in 1994. Around 1992-3 is when the industry had its biggest push towards formulaic writing. If you followed the beats you were supposed to follow and you had three acts and you wrote the plot reversal at the right time and your characters were likable and you had the requisite love story, then you could sell a script, even if you didn’t have a lot of talent.

Over the next couple of years, that belief grew. All you had to do was follow a formula and you’d win the script lottery. 1994 was the ‘culmination year’ of this belief. And you can see that on display here in Bulletproof. This thing feels like it was written by Syd Field.

That’s not necessarily the worst thing. I’ve read too many scripts with no adherence to formula and 99% of them are awful. But if you stick too close to formula, then nothing about your screenplay is going to stand out. Bulletproof unapologetically embraces Hollywood screenwriting.

Starting with the amnesia concept. It was one of the most popular concepts at the time. The set pieces here are all very cliche (escape the hospital, subway chase, chase by foot through city). A love story for no other reason than Hollywood required them at the time. The two even have sex just because you did that in scripts back then, regardless of if it made sense. Biotech companies were all the rage at the time. Heck, it even has one of the most cliche lines you can add to a script: “Who are you to play God!!”

There’s another way to look at this, of course. That the writers were smart. They saw what the industry wanted and they gave them EXACTLY THAT. Lots of writers who visit this site could do well following that advice. What is the industry looking for right now? It’s no secret. Look at what movies Hollywood gives all the promotional dollars to. That’s what they want. So, if you want to make money, that’s one avenue to do it.

But as a script, there’s nothing new here. It feels way way waaaaaaaaaay too familiar. One of the things I hate most about my job is that I’m always so far ahead of the writer. Writers rarely keep me guessing. I wanted this to keep me guessing just a little.

This is yet another reminder to take risks in your screenplays. Don’t do what you’re seeing every other writer do in their movies. When they zig, you zag.

Script link: Bulletproof

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: If you are doing an amnesia or memory-loss screenplay, YOU MUST KNOW THE RULES of your character’s amnesia and stick by throughout the script. You can’t just say, “Memory’s a funny thing. It could come back all at once. Or not at all.” If you don’t know how the rules of your movie’s memory loss works, you’ll take advantage of the ambiguity and have your character forget or remember things whenever it’s most convenient for you and your plot. Readers hate that. If you follow an established rule-set, however, the reader will trust you.

You have to give it to Hollywood.

The town does have a sense of humor.

I mean why else would you plop a Taylor Swift concert movie right in the middle of Horror Season?

The tall gangly crooner does possess a certain “Ichabod Crane” quality, which may have been the secret sauce to getting her film to 100 million dollars. People showed up, fully expecting a Conjuring-like experience. And some of them got it. Looking at 50,000 Swifties blathering through tears is scarier than anything I saw in The Exorcist. But most were like, “Wait, this woman is just singing for 2 hours?”

But in all seriousness, the gigantic haul of Taylor Swift’s film, when seen through the lens of a year that also celebrated Barbie’s titanic box office, has begged the question: Is it time we start writing more for female audiences?

It used to be that men generated all the box office. Young men in particular. Then the post-Bridesmaids era combined with the #metoo movement demanded the industry focus more on female-centric films. They did, to mixed results, but certain films (Captain Marvel, Wonder Woman) proved that the ladies liked to show up. But those were films that catered to both men and women.

This 1-2 Barbie-Swiftie punch has rewritten the box office code. Now, you can make movies for JUST WOMEN and still eclipse 9 figures.

So, this means write movies only for women, right?

Ehhhhhh, let’s dial back the estrogen on that one. The Marvels, a movie designed not just to attract women, but to actively repel men, is coming out on November 10, and its box office tracking is placing it at as the lowest Marvel movie opening ever, less than The Incredible Hulk. Unless they can figure out a last second way to give Slenderman, err, I mean Taylor Swift, a cameo in the film, it’s gearing up to sink the comic book studio faster than the Andrea Doria.

As Taylor Swift would say, “I’m not that… innocent.”

Taylor said that, right?

While the Taylor Swift movie may have been too scary for me, I did want to check out a festive movie this weekend so I went with Poe’s suggestion and fired up, “Totally Killer,” on Amazon.

The film, a slasher version of “Back to the Future,” focuses on Jamie, a high school student whose mother is murdered by the Sweet 16 Killer, a notorious masked serial killer who, 35 years ago, killed 3 teenage girls.

Jamie utilizes the help of her nerdy friend who happens to have built a time machine to travel back to the year 1987. She figures if she can identify and take out the serial killer, she can not only save those three girls, but she can save her mom.

Along the way, she runs into her 16 year old mother, who turns out to be a total bizatch. She’ll have to team up with her, though, to stop the murders. But the other girls are so incredibly stupid that they practically walk into their deaths, no matter what Jamie does. Still, if she can identify the killer, she can hopefully stop the death of her mom.

I can promise you this. Totally Killer was a lot better than the Jack Skellington biopic at theaters this weekend. I mean the Taylor Swift movie.

The movie had a surprisingly edgy sense of humor. There’s a subplot with a couple of dopey 80s cops who do nothing but hang around and chat. Our introduction to them has us eavesdropping on their first conversation: “Old people, sick people, and people with dogs.” There’s a pause and the other cop says, “That’s the order you hate people in?” “Yep.” Not gonna lie. I LOL’d hard.

And conceptually, it’s kind of perfect. Something I’ve told you guys from the get-go is that every screenwriter gets into the game to rewrite their favorite movies. The mistake they all make is that they literally rewrite their favorite movies. So there’s no originality. And the script looks like a big fat ripoff.

Totally Killer shows you the way around this. You take your favorite movie and you move it into another genre. Here, we obviously have Back to the Future. But the writers frame it within the slasher genre. This allows them to copy a lot of the BTTF beats without looking like copycats.

But even beyond that, it’s a surprisingly effective combination. One of the many genius aspects of Back to the Future was how quickly it moved. I’ve found that whenever anyone tries to copy the movie (Peggy Sue Got Married) or replicate that same Michael J. Fox energy (Teen Wolf), the movies just sit there. It shows you just how hard it is to keep the pace up in any plot.

By adding a slasher element to the blueprint, Totally Killer’s plot hits the ground running. The second Jamie ends up in 1987, she’s got to prevent three murders from happening. I thought the writers did a really good job with that.

The movie only has two faults, one small and one big. I thought it could’ve leaned more into the offensive world of the 1980s. It would be a TOTAL SHOCK for a 16 year old girl from 2023 to go to school in 1987. Every safe space she knew would’ve exploded in front of her. And while Totally Killer does some of that (a boy shoves Jamie by the chest as she loudly declares, “Unwanted touch! Unwanted touch!” And the guy doesn’t care nor does anyone sympathize with her), I always say that you need to wring every last drop out of what’s unique about your concept, especially with fish-out-of-water scenarios. Let’s have some TRULY offensive 1980s things happen here.

The bigger issue is one that keeps this from being a classic, and that’s the main actress. She wasn’t right for the role. She’s too dour. Too restrained. Too low-key. Too sarcastic. There’s a reason Back to the Future is one of the top 20 movies of all time. It’s how charming the main actor is.

Totally Killer is kind of like seeing how Back to the Future would’ve played had they kept Eric Stoltz in the lead. The actress, Kiernan Shipka, is meant for more serious rolls. I mean you can see flashes of this being a great film if they had only cast a more charming actress, although now that I’m thinking about it, the female equivalent of Michael J. Fox may not exist. Heck, they haven’t been able to find an equivalent for Michael J. Fox on the guy’s side either.

But if we’re keeping score for the feel-good horror movie of the 2023 Halloween season, Totally Killer gets my vote.

Before we wrap up today’s ode to Peter Cushing, I mean Taylor Swift, I have to exit with a gripe. Rotten Tomatoes needs to place new rules on their horror scoring. There is no other genre they get wrong more than horror. And it’s usually WAAAAAAY over-praising horror content.

After Totally Killer, I was in a good mood. I wanted to pop in another fun horror movie or show, something that could both spook and spike my funny bone. I kept seeing ads for Chucky, the TV show adaptation of the 1980s cult classic, Child’s Play. What caught my eye was the out-of-this-world Rotten Tomatoes scores. We’re talking above 90% for all three seasons!

I thought, this show can’t possibly be that good. But I gave it a chance anyway cause why not. My friends, I watched the pilot for this show. I know certain animals that could’ve directed a better episode of television. It’s not that the show was bad. It’s that it was LIFELESS. From the casting to the production value to the acting to the scene-writing. It was soooooooo so so so so so so boring.

I was unexpectedly pissed that I’d been tricked so badly, since I knew I smelled a rat from the start. I just have to remember that it doesn’t matter what kind of score a show gets. IF IT IS NEVER TRENDING ON SOCIAL MEDIA and IF NO ONE ON THE INTERNET IS WRITING ABOUT IT, it’s bad. That’s all you need to know. I had never seen Chucky mentioned once on social media and I’d never seen anybody write about it. From now on, that’s my gauge for whether to check out a show. I suggest it be yours as well.

Okay, did anybody see the Stephen Merchant film this weekend? I mean Taylor Swift film? What did you think?

Genre: Sci-Fi/Horror/Drama

Premise: Amid a rash of cattle mutilations in the ‘80s, a rural veterinarian holds an alien captive with the desperate hope that its miraculous healing biology can save his terminally ill wife.

About: This is the runner-up in the First Page Showdown. If you’re wondering why we’re reviewing the runner-up and not the winner, it’s a long complicated story but the gist of it is, the winner hadn’t finished his script yet and so we’re waiting on that before we can review it. Actually, that wasn’t long or complicated. It was pretty straightforward. Okay, let’s get to the review. Oh! And remember that we have Halloween Logline Showdown coming up next week. Get those loglines in!

Writer: Mark James

Details: 94 pages

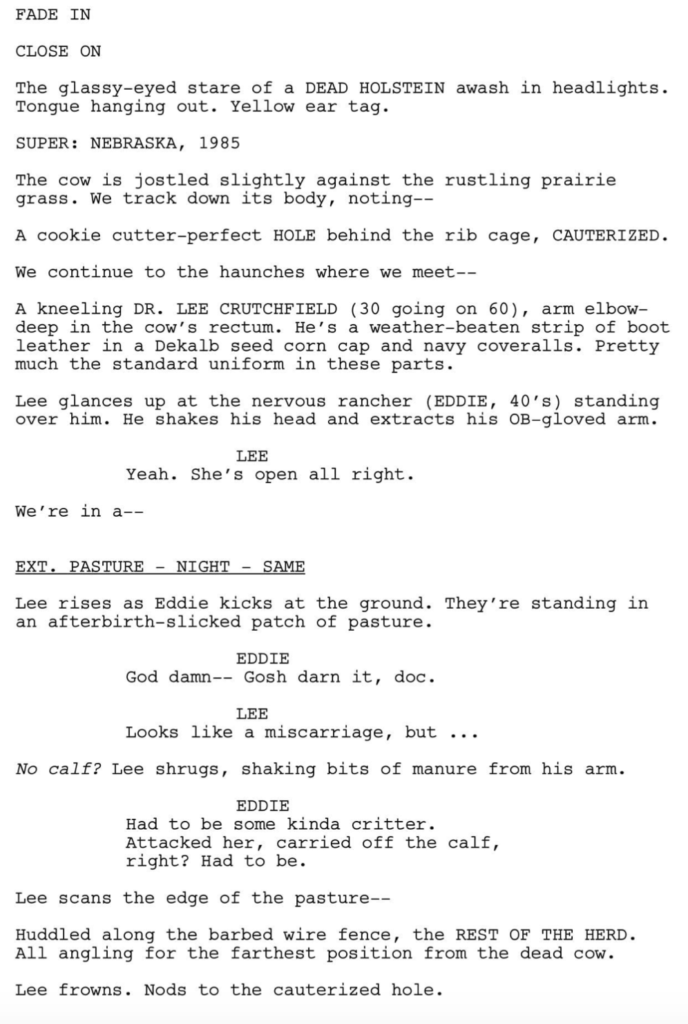

Here’s the first page if you want to reacquaint yourself with it.

Lucky us.

We got a horror script just a week before Halloween Showdown! Sometimes the script gods shine down on us.

BUT!

The script still needs to be good. And the whole reason I picked this first page to compete was because it felt like a different kind of alien movie.

Let’s see if my instincts were right.

The year is 1985. We’re in Nebraska. We meet 30 year-old Dr. Lee Crutchfield as he is elbow deep inside of a dead cow’s rectum. Lee is a vet and although he’s seen a lot, this is not a normal Tuesday night for him. This is actually quite rare.

Word on the street is that cows from all over the local area have been getting mutilated. But Lee’s not buying it. He thinks an animal did this and is vindicated when a rabid badger pops up and he shoots it dead. He tells the rancher he has nothing to worry about, grabs the dead badger and heads back to the clinic to do tests.

Before he does that, though, he heads over to the hospital to see his late 20-s wife, Blair (who he calls “Mother Bear”), who has some sort of weird disease that causes dementia. Her situation is getting worse by the day but Lee is not giving up.

Back at the clinic, Lee spots the dead badger levitating, only to realize it’s being shuttled away by a cloaked 8 foot alien. Lee is able to neutralize the alien with a cattle prod and chain it up. Although the alien is coy at first, it eventually comes clean regarding having the magical ability to cure.

While all this is happening, an Omaha FBI agent named Annabelle Sable shows up who seems to have some knowledge about these aliens. She tells Lee that these off-worlders are not to be trusted! Everything they say is a lie. But all Lee hears is “healing.” So when his wife goes into a coma, Lee decides he’s using the alien cure to save her. But at what cost? And what happens if it doesn’t work?

I had a lot of thoughts swimming through my brain when I finished this script. I knew I could take the review in a familiar direction.

But since this all started with a First Page contest, the question that seemed the most relevant was, “Did I get the script I expected to get from the first page?”

The answer is no.

That’s not a bad thing. It’s just that when I read that first page, I imagined this thoughtful interesting take on aliens where the writer approached things from an angle that we hadn’t seen before. Cause this is a movie about aliens. And most movies about aliens start out with an on-the-nose scene that screams from the mountaintops that the movie is about aliens (i.e. a spaceship in the sky).

By approaching it via a dead cow’s rectum, you told us that this was going to be a different kind of journey (not unlike how we started in Adam Sandler’s rectum in Uncut Gems and got a totally different movie).

And while I suppose you could argue the script does turn out to be different, it ended up feeling too familiar when it was all said and done.

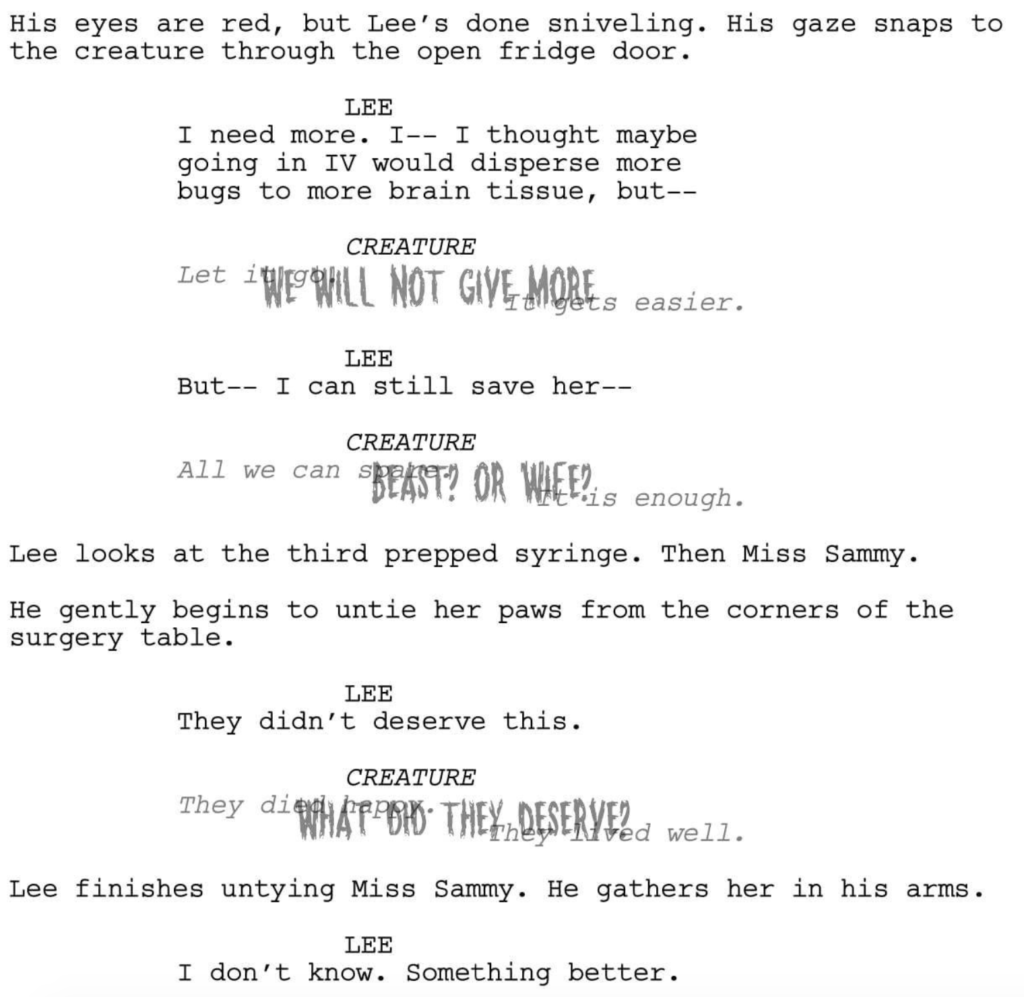

To the writer’s credit, he takes creative risks, the most visual being the alien’s dialogue. This is how all the alien dialogue looks:

What I liked about this choice was that an alien is going to look weird. It’s going to look different. This dialogue style captured that difference in a visual way. When we saw how different it was from normal dialogue, we subconsciously imagined the alien. Which was cool.

But the dialogue was hard to read. The middle part often covered the regular text on either side, which meant I had to squint and move the page around to see what the alien was saying. James also fades the regular text out as the script goes on until it’s practically invisible. So I wasn’t sure if that text even mattered?

Finally, I wasn’t sure how I was supposed to interpret the dialogue. The middle section always contradicted the ends so… I guess that meant the alien was always lying. But it’s still spoken dialogue so didn’t that mean Lee could hear it? All in all, as creative as it was, I felt it was more trouble than it was worth.

The script’s strongest suit is its emotional core – the relationship between Lee and Blair. But I’ll be honest, I had trouble giving in to it. For starters, they’re both late 20s, early 30s. And Blair has dementia. It didn’t read right. A 28 year old with dementia? I’m sure it happens but it happens rarely enough that it creates that dreaded “reading hiccup.” And then the characters called each other Mama Bear and Papa Bear, the kind of nicknames old people use for each other, which confused me, because these characters were young. It just created this clunky vibe to the proceedings that prohibited me from fully enjoying what I was reading.

And while I don’t mean to pile on, this script doesn’t resolve my belief that you can make aliens scary in the way that you can make traditional earthbound creatures and monsters scary.

What happens in The Harvester – and what happens in a lot of these scripts that try to combine horror and aliens – is that, at a certain point, the writer learns that making them scary doesn’t make sense. So it always turns out the the alien is helpful instead of hurtful. We see that here with the alien offering his magical medicine that can heal anything. And, at that point, what are we scared of? We’re not. In retrospect, I’m not sure I was ever scared. And I’m someone who routinely watches scary movies through my fingers.

I mean how scary of an alien can you be when you’re easily restrained by handcuffs? It just didn’t make sense. And I don’t want to dog James because I’ve been down this road before myself. With my own alien-horror scripts which ran into this same problem, and with scripts from other writers that I’ve tried to shepherd. But none of them can ever quite figure out this “aliens being scary” thing. You can do it in flashes. But over the course of the story, it doesn’t make sense for aliens to be scary. Why come 100 light years if you’re going to hide underneath beds and say “boo?”

Overall, as hard as I tried, I couldn’t connect with this script. The horror wasn’t horrifying enough. The sci-fi hit a wall. And the drama was affected by little choices that resulted in an unnecessarily clunky relationship journey.

It wasn’t for me but I’m curious what all of you think. Check out the script below.

Script link: The Harvester

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Whenever I see a writer offer three genres for their script, the first thing I think is, “This writer doesn’t know what kind of story he’s telling.” And that’s how I felt when I read this. “I’m not sure this script knows what it wants to be.” It leans most heavily into the drama side of things. That’s when it’s most comfortable. Cause I think James understood that storyline the best. But this alien who’s sort of dangerous but not really dangerous dictating the majority of the narrative had me scratching my head. It just felt like there was a better story that could be told here. And my gut tells me simplifying the genre is a good place to start.

I stumbled across this video recently while performing a most impressive act of procrastination. I was half-listening at first but as Gervais’s calm soothing British tone gesticulated across me, I found myself subconsciously nodding. I restarted the video and listened more closely.

I’m convinced that what Gervais says here is the single most important factor to writing things that people care about. So much so, I would argue that nobody reading this article today can become a professional writer until they go through this transformation of understanding. They have to accept it, understand it, then execute it, so they can graduate to the other side.

To give you the TLDR of the video, Gervais says that he started out writing fun silly stuff – cop movies where the cop “didn’t play by the rules.” And whenever he turned these scripts into his teacher, the teacher would tell him, “This isn’t any good. Write what you know.”

But Gervais was convinced that people didn’t care about boring truthful everyday stuff. He wanted the fun stuff. The stuff that’s on TV. The stuff he saw in the movies. So he kept writing what he wanted. And he kept getting bad grades.

Finally, he figured he’d pull a fast one on the teacher. As it so happened, every day, his mother would go next door to take care of an elderly woman and sometimes Ricky would go with her. It was the single most boring thing you could write about, in Gervais’s opinion. But it was something “that he knew.”

So he wrote about a day following his mom over to this elderly woman’s house. And he went into excruciating detail. He wanted to make sure that he was writing EVERY SINGLE THING HE KNEW about this experience in order to prove to his teacher that the teacher was wrong and that writing about this sort of thing only led to boring people to death.

I think you know where this is going. When he got the grade back, he’d received his first A. And that’s when the lightbulb went on for Gervais. It isn’t about all the fantastical larger-than-life craziness. It’s about humans connecting with other humans. You achieve this by writing what you know. And because you’re writing what you know, you are writing THE TRUTH. And THE TRUTH is the single most important part of getting readers to connect with your writing.

This isn’t the first time I’ve heard a writer share this story. I hear a lot of writers say this was the moment they finally understood writing. Neil Gaiman talks about how nobody cared about his writing until he started “telling the truth.”

But what is “the truth?” What does “the truth” look like?

It starts with, like Gervais says, “What you know.” For there is nothing you know more truthfully than your own life.

I used to teach tennis, as some of you know. So let’s use that as our theoretical backdrop. We’ve got Writer 1, who took a couple of tennis lessons when he was a kid and wants to write a movie about a tennis pro. Then we’ve got Writer 2, who taught tennis for ten years, and wants to write a similar movie (me).

The first scene of Writer 1’s movie is probably going to be our tennis pro showing up at the Beverly Hills Country Club or a similar upscale tennis place. He’s got his tennis whites. He’s got a 5 o’clock shadow. He makes some funny quips to a few co-workers, as well as the hottie tennis pro he’s dating. She asks if they’re still having lunch later. Of course. He rushes out to teach his first lesson, a sexy MILF who’s giving him googly eyes the second he steps on the court. He tries to teach her but she can’t help but make a bunch of sexual innuendos during the lesson. Afterwards, she proposes that all future lessons take place at her private tennis court. He has to practically slip out of her grip to get away from her. And that’s the first scene.

Now, let me tell what a morning with me was like as a tennis pro.

I would ride my bike to work because my car was always broken. I had timed it so I got to work at exactly 8am. That way I could technically say that I was on time, even though it would take me another five minutes before I got on the court and started my lesson, to a client who was in no way interested in or trying to flirt with me. They were just mad because their lesson was going to start late.

Now, I didn’t teach at Beverly Hills. I taught at Westwood Tennis. A park. Which meant that I would have to wake up the homeless person sleeping in front of the tennis shack door every morning and tell him to get out of the way so I could go inside.

After he took his sweet time, I would go inside and begin looking for the necessary tools I needed to teach my lessons. One thing you have to realize about tennis pros is that they’re always breaking their strings. Cause they’re playing all day. We all had 3 or 4 rackets but we would eventually break the strings on those rackets too. And since we’re all so lazy, we don’t get them restrung. Instead, we use the demo rackets, which we’re not supposed to use cause those are reserved for clients to help motivate them to buy said overpriced rackets. Since all the pros would snatch these demos – because they’re all breaking their strings too – the demo racket strings would break as well.

When this happened, we’d start using the kid’s demo rackets. These rackets were much smaller and way flimsier and, most importantly, they didn’t look professional. Half of them were girl’s rackets for 10 year olds that had Disney themes on them. Which meant that, it wasn’t uncommon for me to walk on the court with a tiny pink Little Miss Mermaid tennis racket. This when I would occasionally have to play with advanced players. That never went over well.

But the racket wasn’t even the main problem. The main problem was the tennis balls. All us pros were responsible for our own tennis balls. We had to buy them ourselves. And when you have to buy 50 cans of tennis balls at $3.50 a pop, that adds up. Especially when all of the annoying beginner players keep hitting the balls over the fence where they would vaporize to never be seen again. This would annoy me to such a degree that, for a while, I had a rule, that if any of my lessons hit the ball over the fence, they had to stop playing immediately and go retrieve it. They weren’t allowed to come back until they found it.

With the constant dwindling tennis ball supply there was a lot of ball thievery going on. If a pro had gotten so lazy as to not buy new balls in a long time, their ball cart wouldn’t have enough balls for a lesson. So if we were the one with the depleted cart (which I often was) we would steal balls from the other tennis pros’ carts when they weren’t around. Tennis ball stealing became so rampant that each pro started buying multiple locks to lock the top of their tennis ball carts so you couldn’t steal their balls

This never stopped me. I would reach my hand down through the sides of my fellow tennis pros’ carts, scraping the insides of my arms to the point of bleeding as I fished out one agonizing ball at a time until I had enough to teach my lesson. It got so bad that everyone would mark their balls with their initials in permanent marker. This did not deter me if I needed balls bad enough. You can’t show up to a lesson with 15 balls. You’ll be done feeding balls within 2 minutes.

I could go on. But I think you get the point. The first writer writes the generic version of being a tennis pro because they don’t know any of the truths that go into teaching tennis. They’ve never done it before. Whereas I have over a million unique details of what goes on as a teaching pro. And most of them are surprising. I doubt any of you would’ve guessed that that was an average morning for a tennis pro.

By the way, if you want to see a real world example of Writer 1 in action, go watch the pilot episode of “Based on a True Story” on Peacock. The main guy character is a tennis teacher and they write him almost exactly the way Writer 1 wrote it. There’s zero truth to it and you’ll notice how detached you feel from his tennis storyline for that reason.

I suspect this is why I hate shows like Ahsoka right now. I don’t feel any truth at all when I watch that show. Granted, it’s much harder to write what you know if you’re writing fantasy or sci-fi or an action film that takes place in Casablanca. You’ve never been to Casablanca so how are you going to make that sound truthful?

Well, the answer to that is, YOU’RE NOT. You really aren’t. No matter how hard you try. What you should do instead is pick a concept that covers subject matter you know well. The chances of you writing something that will resonate with others will go up exponentially.

But we also have to be realistic. Some writers like writing fantastical stories. And it’s unrealistic to think that you’ll never run into story sequences that don’t have some elements that you’re unfamiliar with. So what do you do if that’s the case?

The answer, believe it or not, is simple. While you won’t be able to write about subject matter that you know, you can always write CHARACTERS THAT YOU KNOW. And if you’re writing characters you know, the character side of your story will be truthful.

This is why it’s a smart idea to base your main character on yourself. Or some aspect of yourself. That way, you’ll be able to write them truthfully. I always tell writers, figure out what your biggest struggle is at this moment in your life. Then have your main character going through the same thing.

If you’re struggling through a hard divorce, your hero should be struggling through a hard divorce. If you’re struggling with belief in yourself, your hero should struggle to believe in himself. If you’re trying to emerge out of the shadow of a successful parent? Yeah, I think you get what you have to do.

Then apply this same approach to as many characters in the story as you can. Base some on other parts of you. Maybe there’s another part of you that’s frustrated that you can’t stand up for what you want. So give that flaw to a supporting character. And for the rest of the characters, base them on people you know or who you’ve met throughout your life. Figure out what represented those people and simply transfer it over to your characters.

If you can do this with your characters, you can write big elaborate screenplays and still have them feel grounded and truthful. Cause all your characters will act with an underlining sense of truth. And you’re writing what you know. If you want to see this in action, check out James Gunn’s studio movies. He’s good at writing gigantic fanciful movies yet still finding the humanity in all the characters. I’m convinced he does that by writing what he knows and always staying truthful.

I can promise you this. If you write a giant action plot for a subject you’ve never had any personal experience with and then you ALSO don’t build your characters around truth, your script is dead in the water. This is something all writers have to figure out if they want to write great stories.

So get to work!

And I’ll be back tomorrow to finally review our second place script for the First Page Showdown!