Genre: Horror

Premise: A group of paranormal researchers move in to the most haunted mansion in the world to try and prove the existence of ghosts.

About: One of our longtime commenters has thrown his hat into the ring. Very excited to finally be reviewing Andrew Mullen’s script! — Every Friday, I review a script from the readers of the site. If you’re interested in submitting your script for an Amateur Review, send it in PDF form, along with your title, genre, logline, and why I should read your script to Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Keep in mind your script will be posted.

Writer: Andrew Mullen

Details: 146 pages (This is an early draft of the script. The situations, characters, and plot may change significantly by the time the film is released. This is not a definitive statement about the project, but rather an analysis of this unique draft as it pertains to the craft of screenwriting).

Andrew’s been commenting on Scriptshadow forever and I like to reward people who actively participate on the site, so I was more than happy to choose his script for this week’s Amateur Friday. Seeing that Andrew had always made astute points and solid observations, I was hoping for a three-for-three “worth the read” trifecta over the last three Amateur Fridays. What once seemed impossible was shaping up to be possible.

And then I saw the page count.

Pop quiz. What’s the first thing a reader looks at when he opens a screenplay? The title? No. The writer’s name? No. That little box on the top left corner of the PDF document that tells you how many pages it is? Ding ding ding! I saw “146” and my eyes closed. In an instant, all of the energy I had to read Shadows was drained. I know Andrew reads the site so I know he’s heard me say it a hundred times: Keep your script under 110 pages. Of all the rules you want to follow, this is somewhere near the top. And it has nothing to do with whether it’s possible to tell a good story over 110 pages. It has to do with the fact that 99.9% of producers, agents, and managers will close your script within 3 seconds of opening it after seeing that number. They will assume, rightly in 99.9% of the cases, that you don’t know what you’re doing yet, and move on to the next script.

Which is exactly what I planned to do. I mean, I have a few hundred amateur scripts that don’t break the 100 page barrier. I would be saving 45 minutes of my night to do something fun and enjoyable if I went back to the slush pile. But then I stopped. I thought, a) I like Andrew. b) This could serve as an example to amateur writers WHY it’s a terrible idea to write a 146 page script. And c) Maybe, just maybe, this will be that .01% of 146 page screenplays that’s good and force me to reevaluate how I approach the large page count rule.

So, was Shadows in that .01%?

Professor Malcom Dobbs and Dr. Butch Rubenstein are founders of the premiere paranormal research team on the planet. They’re the “Jodie Foster in Contact’s” of the paranormal world, willing to go to the ends of the earth to prove that ghosts do, in fact, exist. And they’re currently residing in the best possible place to prove this – a huge mansion with sprawling grounds known as Carrion Manor – a house many consider to be the most haunted in the world.

But with their grant running out, so is their time to prove the existence of ghosts, so the group is forced to take drastic measures. They head to a local nut house and ask for the services of 20-something Brenna, a pretty and kind woman with a dark past. Her entire family was slaughtered when she was a child, and that night she claimed to have heard voices, whispers, contact from another realm. This “contact” is exactly what our team needs to ramp up their experiments.

Basically, what these guys do is similar to the “night vision” sequence in the great horror film, “The Orphanage,” where they use all their technical equipment like computers, and cameras, and microphones, to monitor levels of energy as Brenna walks from room to room throughout the manor. This is one of the first problems I had with the script. There isn’t a lot of variety to these scenes. And we get a lot of them. Brenna walks into a room. The levels spike. Our paranormal team is excited. Some downtime. Then we repeat the process again.

During Brenna’s stay, she starts to fall for one of the team members, a child genius (now 27 years old) named Dr. Schordinger Pike. This was another issue I had with the script, as the development of Pike and Brenna’s relationship was way too simplistic, almost like two 6th graders falling in love, as opposed to a pair of 27 year olds (“She’s way out of my league. Right? Right. Not even the same sport!” Pike starts hyperventilating). Also, I find that when the love story isn’t the centerpiece of the film (in this case, the movie is about a haunted mansion) you can’t give it too much time. You can’t stop your screenplay to show the two lovers running through daisies and professing their love for one another. You almost have to build their relationship up in the background. Empire Strikes Back is a great example of this. Han and Leia fall in love amongst a zillion other things going on. Whereas here, we stop the story time and time again to give these two a scene where they can sit around and talk to each other. Always move your story along first. Never stop it for anything.

Anyway, another subplot that develops is the computer system that’s monitoring the house, dubbed “Casper.” Casper is the “Hal” of the family, and when things start going bad (real ghosts start appearing), Casper wants to do things his way. You probably know what I’m going to say here. A computer that controls the house is a different movie. It has nothing to do with what these guys are doing and therefore only serves to distract from the story. You want to get rid of this and focus specifically on the researchers’ goal (trying to prove that there are ghosts) and the obstacles they run into which make achieving that goal difficult.

I will say there’s some pretty cool stuff about the eclectic group of former house owners, and the fact that a lot of them had unfinished business when they died clues us in that we’ll be seeing them again. And we do. The final act is 30 intense pages of paranormal battles with numerous ghosts and creatures coming to take down our inhabitants, some of whom fall victim to the madness, some of whom escape. But there are too many dead spots in the script, which makes getting to that climax a chore.

So, the first thing that needs to be addressed is, “Why is this script so long?” I mean, did we really need this many pages to tell the story? The simple and final answer is no. We don’t need nearly this many pages. The reason a lot of scripts are too long is usually because a writer doesn’t know the specific story they’re trying to tell, so they tell several stories instead. And more stories equals more pages. This would fall in line with my previous observation, that we have the needless “Casper” subplot and a love story that requires the main story to stop every time it’s featured.

Figure out what your story is about and then ONLY GIVE US THE SCENES THAT PUSH THAT PARTICULAR STORY FORWARD. Doesn’t mean you can’t have subplots. Doesn’t mean you can’t have a minor tangent or two. But 98% of your script should be working to push that main throughline forward. So if you look at a similar film – The Orphanage – That’s a film about a woman who loses her son and tries to find him. Go rent that movie now. You’ll see that every single scene serves to push that story forward (find my son). We don’t deviate from that plan.

Another problem here is the long passages where nothing dramatic happens. There’s a tour of the house that begins on page 59 that just stops the story cold. We start with a couple of flirty scenes between Brenna and Pike as we explore a few of the rooms. Then we go into multiple flashbacks of the previous tenants in great detail, one after another. After this, Pike offers us a flashback of his OWN history. So we had this big long exposition scene regarding the house. And we’re following that with another exposition scene. Then Pike shows Brenna the house garden, another key area of the house, and more exposition. This is followed by another character talking about a Vietcong story whose purpose remains unclear to me. The problem here, besides the dozen straight pages of exposition, is that there’s nothing dramatic happening. No mystery, no problem, no twist, nothing at stake, nothing pushing the story forward. It’s just people talking for 12 minutes. And that’s the kind of stuff that will kill a script.

Likewise, there are other elements in Shadows that aren’t needed. For example, there’s a character named Lewis, a slacker intern who never does any work, who disappears for 50-60 pages at a time before popping back up again. We never know who the guy is or why he’s in the story. Later it’s discovered he’s using remote portions of the house to grow pot in. I’m all for adding humor to your story, but the humor should stem from the situation. This is something you’d put in Harold and Kumar Go To Siberia, not a haunted house movie. Again, this is the kind of stuff that adds pages to your screenplay and for no reason. Know what your story is and stay focused on that story. Don’t go exploring every little whim that pops into your head – like pot-growing interns.

This leads us to the ultimate question: What *is* the story in Shadows? Well, it’s almost clear. But it needs to be more clear. Because the clearer it is to you, the easier it will be to tell your story. These guys are looking for proof of the paranormal. I get that. But why? What do they gain by achieving this goal? A vague satisfaction for proving there are ghosts? Audiences tend to want something more concrete. So in The Orphanage, the goal is to find the son (concrete). In the recently reviewed Red Lights, a similar story about the paranormal, the goal is to bring down Silver (concrete). If there was something more specific lost in this house. Or something specific that happened in this house, then you’d have that concrete goal. Maybe they’re trying to prove a murder or find a clue to some buried treasure on the property? Giving your characters something specific to do is going to give the story a lot more juice.

Here’s the thing. There’s a story in here. Paranormal guys researching ghosts in the most haunted house in the world? I can get on board with that. And there’s actually some pretty cool ideas here. Like the old knight who used to live on the property who was never found. There’s potential there. But this whole story needs to be streamlined. I mean you need to book this guy on The Biggest Loser until he’s down to a slim and healthy 110 pages. Because people aren’t going to give you an opportunity until you show them that you respect their time. I realize this is some tough love critiquing going on here, but that’s only because I want Andrew to kick ass on the rewrite and on all his future scripts. And he will if he avoids these mistakes. Good luck Andrew. Hope these observations helped. :)

Script link: Shadows

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: This script was a little too prose-heavy, another factor contributing to the high page count. You definitely want to paint a picture when you write but not at the expense of keeping the eyes moving. Lines like this, “A dying jack o’ lantern smiles lewdly. The faintly glowing grimace flickers in the dark as if struggling for life,” can easily become “A flickering jack o’ lantern smiles lewdly,” which conveys the exact same image in half the words. Just keep it moving.

So you want to write an Oscar-winning screenplay. Well, I thought I’d have a little fun this week and look back at the last 25 Oscar winners in the best Original Screenplay category and see if I can’t lock down a pattern or two as to what kind of script wins this most prestigious of competitions. If this is, indeed, a collection of the best writing over the past 25 years, it wouldn’t hurt to figure out what these writers are doing. So below, I’ve listed the last 25 Oscar Winners in order (from 1986 to 2010) and afterwards, I’ll share with you nine observations I found from combing through the list. Your Oscar winners ladies and gentleman…

1986 – Hannah and Her Sisters (Woody Allen)

1987 – Moonstruck (John Patrick Shanley)

1988 – Rain Man (Ronald Bass and Barry Morrow)

1989 – Dead Poets Society (Tom Schulman)

1990 – Ghost (Bruce Joel Rubin)

1991 – Thelma and Louise (Callie Khouri)

1992 – The Crying Game (Neil Jordan)

1993 – The Piano (Jane Campion)

1994 – Pulp Fiction (Quentin Tarantino and Roger Avary)

1995 – The Usual Suspects – Christopher McQuarrie

1996 – Fargo (Joel and Ethan Coen)

1997 – Good Will Hunting (Matt Damon and Ben Affleck)

1998 – Shakespeare In Love – (Marc Norman and Tom Stoppard)

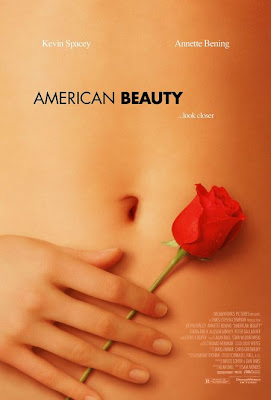

1999 – American Beauty (Alan Ball)

2000 – Almost Famous (Cameron Crowe)

2001 – Gosford Park (Julian Fellowes)

2002 – Talk to Her (Pedro Almodovar)

2003 – Lost In Translation (Sophia Coppola)

2004 – Eternal Sunshine of The Spotless Mind (Pierre Bismuth, Michael Gondry, Charlie Kaufman)

2005 – Crash (Paul Haggis)

2006 – Little Miss Sunshine (Michael Arndt)

2007 – Juno (Diablo Cody)

2008 – Milk (Justin Lance Black)

2009 – The Hurt Locker (Mark Boal)

2010 – The King’s Speech (David Siedler)

DISPARITY

First thing I noticed about the Oscar winners is how much disparity there is in the genres. We start with an ensemble comedy, move to a romantic comedy, then to a road trip buddy drama, then to an inspirational teacher movie, then to a supernatural romantic drama. Our most recent five are a “wacky family” movie, a teenage comedy-drama, a gay rights leader biography, a war film, and a period piece. Naturally, my first inclination is to say, “There are no patterns in this! The Academy just picks whatever the best script is that year.” Kinda cool. But wait, I looked a little deeper and, what do you know, I was able to find some commonalities…

DRAMA!

Fifteen of the 25 scripts listed are dramas. That’s an even 60%. This would make sense, as drama is the genre most reflective of real life and therefore the vessel most likely to put us in touch with our emotions. Unlike thrillers and horror and action movies, which take us to places we’ll never go in our real lives, drama places a mirror up to us and says, “Hey, this is you buddy.” From losing your job like Lester Burnham in American Beauty to taking a stand for an issue you believe in like in Milk. This is the most affecting genre in film when done right, so naturally, it’s going to result in some of the most affecting films. Now while this DIDN’T surprise me that much. The next trend I saw did. Because this is the last thing you’d expect the Academy to celebrate….

HUMOR!

The Academy has a bad rap for not recognizing comedies the way they do other genres. But take a look at the movies on this list. Almost all of them make you laugh. Sure, most of the time, the humor is dark, but Almost Famous, Rain Man, Moonstruck, Pulp Fiction, Ghost, Fargo, Good Will Hunting, Juno, Crash, Eternal Sunshine, Little Miss Sunshine. There is a lot of humor in those movies. This is a huge revelation for me. Because when you think of the stodgy Old Guard that is the Academy, you think you have to go all drama all the time. This proves that infusing your script with comedy, albeit balanced with drama, is just as important.

DON’T BE AFRAID TO ENTERTAIN

One thing I expected to find when I pulled this list out was something akin to the Nichol Winner choices – since they’re operating under the same umbrella – scripts that specifically focused on a deeper element of the human condition (and I did find a few: Milk, The Hurt Locker). But I was surprised at just how many films wanted to entertain you. Juno, Fargo, Gosford Park, Pulp Fiction, Ghost, Almost Famous, The King’s Speech. These movies just want you to have a good time in the theater first, AND THEN if you want to look deeper, they serve you an extra helping of warmed up leftovers to dig into later. I think when people sit down and think, “I want to write an Oscar screenplay,” they get into this mentality that they have to change the world with every word. But there’s enough of an entertainment factor to all these movies that I think the old saying, “Entertain first, teach second,” is the way to go.

THERE’S AN ELEMENT OF LUCK TO WRITING A SCREENPLAY

One of the scariest realizations I had going over this list is that there is a huge amount of luck involved in writing a great screenplay. And I don’t mean that writing doesn’t require skill. What I’m saying, rather, is that sometimes a story just comes together and sometimes it doesn’t. And we don’t always know if it’s coming together until we’re well into writing it. I say this because in the last 25 years, there has been a different winning screenwriter in the original screenplay category every single year. And there is only one writer (or pair of writers) who have won twice if you include the adapted category, and that’s Joel and Ethan Cohen for both Fargo and No Country For Old Men. You would certainly think that, if you’re good enough at your profession, you would continue to win at least somewhat consistently over the course of your career. But the opposite is true in this category. What this tells me is that the screenplay is the star, not the screenwriter, and I don’t say that to diminish the work of the writer, but rather to remind you, if you come up with a good idea that seems to be working on the page, nurture that thing and make it the best you possibly can. Because like it or not – even for the best screenwriters – the great idea combined with the perfect execution just doesn’t come around very often.

LEARN TO DIRECT

Nine of these winners directed their screenplays. That’s 36%. Although I sometimes question the writer-director approach (writer-directors may be too close to the material to be objective), it’s clear from this number that the approach pays off. This is probably because directors write with a director’s point of view, which is a little different than a writer’s point of view. They can visualize cinematic sequences they know will work, whereas a screenwriter might know that sequence will read terribly on paper and ditch it. Take the 12 minute dialogue scene in Jack Rabbit Slim’s in Pulp Fiction for example. That would never survive in a spec script. The producers would scream foul at a 12 minute dialogue scene with 2 people sitting at a table. But Tarantino can visualize the setting, the characters, the mood, the tone, and know it will work. This freedom allows the writer-director to write things differently, and the Oscar-voting crowd likes rewarding things that are different.

TRENDING TOWARDS THE SINGLE PROTAGONIST

A lot of these winners consist of an ensemble cast (American Beauty, Crash, Gosford Park, Little Miss Sunshine, Fargo, Hannah and Her Sisters, Pulp Fiction). Cutting back and forth between multiple storylines seems to get the Academy’s juices flowing. However, I noticed that the past four winners more or less follow the traditional singular hero journey that is so often taught by screenwriting books and gurus. They may not be executed on the same basic level as Liar Liar or Taken, but the single hero journey it is. So don’t feel like you have to populate your story with multiple characters and multiple intersecting timelines to get the Academy’s attention. You can follow just one guy. Just make sure that guy is interesting!

NEVER FORGET THE POWER OF THE IRONIC CHARACTER

Robin Williams is a therapist who doesn’t have his shit together. Matt Damon is a janitor who’s a mathematical genius. Dustin Hoffman is a mentally challenged man who’s a genius at black jack. Colin Firth plays a king who’s unable to speak to his people. Audiences are fascinated by ironic characters, those who are in some way opposite from the image they project. These characters are by no means necessary to write a great script, but if you can work one into your story, it’s going to make you and your script look a lot more clever, which should give you a bump come Oscar time.

TAKE HEED LOW-CONCEPTERS

For those of you out there worrying that your script is too low concept, you might want to toss your hat in the ring for an Academy Award. Truth be told, very few of these loglines scream “I have to read this now!” The exceptions might be Ghost, Rain Man, Eternal Sunshine, and Shakespeare In Love. However, it’s important to remember that almost everyone on this list had a previous level of success in the industry which guaranteed that their screenplay would get read by others. Who knows how long these great scripts might have sat on a pile unread because the loglines were average and they were written by Joe Nobody. So I still think the best roadmap to success is to write that high-concept comedy or thriller first, THEN bust out your multi-character period piece about a prince suffering from whooping cough second, in order to snatch that Oscar you so richly deserve.

So, that’s what I found. Did I miss anything? I noticed that a lot of these scripts were written by a single person as well, so time to dump your writing partner (kidding). I still feel like there’s a magical formula here as there definitely seems to be a similarity with all these scripts that I can’t put my finger on. So I’ll leave that up to you. Enjoy discussing.

Genre: Drama/Comedy

Premise: A New Yorker heads back to the small liberal arts college he attended to give a speech for a retiring professor and ends up falling for one of the students while he’s there.

About: Radnor is the writer-director of one of my favorite scripts, which used to be on my Top 25, Happy Thank You More Please. This is his follow-up project, which will star him and new IT girl Lizzie Olsen after her breakout turn in Sundance hit, “Martha Marcy May Marlene,” about a girl who grows up on a hippie convent.

Writer: Josh Radnor

Details: 115 pages (This is an early draft of the script. The situations, characters, and plot may change significantly by the time the film is released. This is not a definitive statement about the project, but rather an analysis of this unique draft as it pertains to the craft of screenwriting).

I still can’t get over it. I still can’t handle the fact that an actor making $400,000 an episode on a silly sitcom is also one of the best screenwriters in Hollywood. Don’t agree with me? Okay, let’s narrow the playing field a little. He’s not going to write the next Heat. But there is no one who’s doing the “lost early mid-life crisis” thing better at this moment than Radnor. He’s Cameron Crowe before Elizabethtown

. He’s Woody Allen before, well, his last 15 movies. He’s a way more sophisticated Zach Braff

. There’s an honesty and an intelligence to his writing that you just don’t see that often. Naturally, I couldn’t wait to read his second script.

And it started off perfectly, almost like a parallel universe continuation of his last film. Jesse Aaron Fisher is 35 and works a mindless college recruitment job in New York City. High school students come in, ask questions, he gives them stock answers, they leave, repeat.

Jesse has one thing that keeps him going. Books. He looooooves books. Oh, I mean he really loves books. His ex, who just broke up with him, comes over to his place to get her stuff, and instead of taking advantage of this last opportunity to repair their relationship, he reads a really awesome book instead.

Jesse also loves college. Or loved college. It’s been 13 years since he finished his small liberal arts education, and boy does he miss it. So when one of his favorite professors and good friends calls to inform him he’s folding up the chalkboard and would like Jesse to speak at his retirement party, Jesse can’t jump in his car fast enough.

From the moment he reaches campus, Jesse is a different man. There’s a pep in his step, a smile on his lips, a life surrounding his bones. The vibe on this tiny little campus is more electric than all of New York City put together. And it’s just about to jump a few volts higher.

Jesse runs into one of the students there, the cute and way more intelligent than the average college kid, Zibby. She seems to be just what Jesse needs at the moment, someone to excite him, to remind him to loosen up, to be young again. And so when Jesse runs into her a second time at a dorm room party, so begins a very tense very sexually charged friendship.

And yes, I know what you’re thinking. I know you think you already know where this is going. I know that because I thought the same thing. But guess what? You don’t know. You don’t have a clue. In fact, we deviate quite severely from the typical garden variety older guy younger girl romance.

They don’t hook up. Instead Jesse goes back to New York. The two start writing each other, getting to know each other on a deeper level, and then, after some time has passed, he comes back to the college (spoilers), but right before he’s about to seal the deal, questions what the hell he’s doing, and starts having a mini-mental breakdown on top of his early mid-life crisis, and goes fleeing in the opposite direction, as far away from Zibby as possible.

In the end, the story becomes more about Jesse figuring himself out, rather than figuring out him and Zibby, and so for better or worse, a sort of offbeat indie romantic comedy becomes a full-blown coming-of-age film. It’s strange and unexpected and different and is the reason I’m so damn confused about how I feel about the script.

You should know me well enough by now to know that, for the most part, I like clean narratives. I like when stories have clear places to go, where we understand the direction of the plot, where we’re staying in the same general vicinity for the majority of the story (unless the genre dictates something else – like a spy or action flick). Liberal Arts doesn’t follow that template. I thought for sure that once we got to the school, we would stay at the school. And when we didn’t, I was confused but still willing to give it a go. However, we’re jumping back and forth between the school and New York so much, and we’re travelling so much and sending so many letters, that at a certain point I began to wonder if it wouldn’t have been a lot easier to go the more traditional route.

Here’s my take on it. You want your characters in the place that produces the most amount of conflict. Two characters 500 miles away? No conflict. Those same characters – who for a number of reasons shouldn’t be together (the main one being their age difference) – stuck on the same campus together? Conflict. Now I can excuse this if the concept of the movie is based around separation (Going The Distance) but the central element of conflict in this case, Jesse’s reluctance to engage in an “inappropriate” relationship, doesn’t work unless the inappropriateness is placed in front of him at all times. If you can’t reach the cookie jar, the question of whether you will isn’t a factor. But if it’s right there at eye level, always there for the taking, then the question of whether you will or won’t becomes a lot more interesting.

I’m so torn up about this script because I absolutely loved the first half. I mean I loved it. The thing with Radnor though is that he’s going to give you something different. He did it in Happy Thank You More Please when he threw a 35 year old man, a kid he found off the street, and a fuck buddy, into an impromptu family. And he does it here. Where you think this is going to be like Point A, where a guy starts dating a much younger girl. But it isn’t. It’s about a guy who’s ABOUT to date a much younger girl, then realizes it’s wrong and backs out of it.

So I guess I should be rewarding Radnor for not falling victim to cliché and obviousness. Yet a part of me feels like I just spent all night flirting with a girl at a bar and then at the end of the night she went home with someone else. 70 pages have been spent setting up this relationship. To rip it out from under our feet like that is at least a little deceitful, right?

Radnor also eschews other suggested Scriptshadow practices, like giving the main character a goal. There is no goal here, and therefore nothing driving the story other than the question of, “Will Jesse and Zibby get together?” On the list of devices that can drive your story, I always rate this one pretty low, because it allows for too much wandering about. Without pursuits, the characters just sort of exist in their day to day lives, so by the time we get around to that question being answered, it’s too late, since we’ve already lost interest. I know of only one movie where that’s the ONLY thing driving the story and it’s still worked, and that’s When Harry Met Sally. So I always suggest avoiding it unless you have some unique way of making it work.

And while I liked Jesse at first, I thought it was interesting that Radnor made him less likable as the script went on (the arc of most characters is the opposite – they start off unlikeable, then we’re given reasons to like them along the way). There’s a whole sequence where Jesse finds out that Zibby’s read Twilight and literally freaks out. He’s so upset about it that he actually chastises her for even contemplating reading the book. It’s somewhat necessary in that it’s the final straw in making him realize that him and Zibby aren’t meant for each other. But I’m not sure Radnor realizes how unlikeable it makes Jesse. I mean, I hate Twilight as much as the next guy. But I think anybody who appreciates art understands that, in the end, taste is in the eye of the beholder. For him to be so cruel to Zibby after finding that book – I don’t know – it just really distanced me from the character.

I know I’m giving a lot of flak to my screenwriter crush Radnor, but I felt he made some choices in the second half that, while different, made the story less satisfying. Still, I loved all the touches, such as accidentally falling asleep on the quad lawn then waking up in the middle of the night (nothing like a random 35 year old man falling asleep in the middle of your college campus). The roommate that keeps popping in at the most inopportune times. The classic college hippy guy who’s always sharing his whacked out but not nearly as deep as he thinks they are philosophies. Radnor continues to have some of my favorite guy-girl dialogue as well. It’s not so much the kind you quote. But it’s fun and honest without being showy, never an easy line to walk.

Anyways, this was a frustrating read for me. I loved parts of it and I hated parts of it. So my final verdict falls somewhere in the middle. Should be interesting to see where it goes since, now that he has a movie under his belt, it will get a lot more attention.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Remember guys. A break-up scene including your main character at the beginning of your script DOES NOT HAVE TO HAPPEN AT A RESTAURANT. In fact, it doesn’t even need to happen at all. Here, in Liberal Arts, the break-up has already happened. And the post-break-up scene takes place at our hero’s apartment, with his ex coming by to get her stuff. I realize we’ve seen this scene before, but not nearly as much as the break-up at restaurant scene that opens 43% of all comedy specs. Please, no more break-up at restaurant scenes starting your movie! You are more original than that. I promise you!

Genre: Drama/Comedy

Premise: A New Yorker heads back to the small liberal arts college he attended to give a speech for a retiring professor and ends up falling for one of the students while he’s there.

About: Radnor is the writer-director of one of my favorite scripts, which used to be on my Top 25, Happy Thank You More Please. This is his follow-up project, which will star him and new IT girl Lizzie Olsen after her breakout turn in Sundance hit, “Martha Marcy May Marlene,” about a girl who grows up on a hippie convent.

Writer: Josh Radnor

Details: 115 pages (This is an early draft of the script. The situations, characters, and plot may change significantly by the time the film is released. This is not a definitive statement about the project, but rather an analysis of this unique draft as it pertains to the craft of screenwriting).

I still can’t get over it. I still can’t handle the fact that an actor making $400,000 an episode on a silly sitcom is also one of the best screenwriters in Hollywood. Don’t agree with me? Okay, let’s narrow the playing field a little. He’s not going to write the next Heat. But there is no one who’s doing the “lost early mid-life crisis” thing better at this moment than Radnor. He’s Cameron Crowe before Elizabethtown

. He’s Woody Allen before, well, his last 15 movies. He’s a way more sophisticated Zach Braff

. There’s an honesty and an intelligence to his writing that you just don’t see that often. Naturally, I couldn’t wait to read his second script.

And it started off perfectly, almost like a parallel universe continuation of his last film. Jesse Aaron Fisher is 35 and works a mindless college recruitment job in New York City. High school students come in, ask questions, he gives them stock answers, they leave, repeat.

Jesse has one thing that keeps him going. Books. He looooooves books. Oh, I mean he really loves books. His ex, who just broke up with him, comes over to his place to get her stuff, and instead of taking advantage of this last opportunity to repair their relationship, he reads a really awesome book instead.

Jesse also loves college. Or loved college. It’s been 13 years since he finished his small liberal arts education, and boy does he miss it. So when one of his favorite professors and good friends calls to inform him he’s folding up the chalkboard and would like Jesse to speak at his retirement party, Jesse can’t jump in his car fast enough.

From the moment he reaches campus, Jesse is a different man. There’s a pep in his step, a smile on his lips, a life surrounding his bones. The vibe on this tiny little campus is more electric than all of New York City put together. And it’s just about to jump a few volts higher.

Jesse runs into one of the students there, the cute and way more intelligent than the average college kid, Zibby. She seems to be just what Jesse needs at the moment, someone to excite him, to remind him to loosen up, to be young again. And so when Jesse runs into her a second time at a dorm room party, so begins a very tense very sexually charged friendship.

And yes, I know what you’re thinking. I know you think you already know where this is going. I know that because I thought the same thing. But guess what? You don’t know. You don’t have a clue. In fact, we deviate quite severely from the typical garden variety older guy younger girl romance.

They don’t hook up. Instead Jesse goes back to New York. The two start writing each other, getting to know each other on a deeper level, and then, after some time has passed, he comes back to the college (spoilers), but right before he’s about to seal the deal, questions what the hell he’s doing, and starts having a mini-mental breakdown on top of his early mid-life crisis, and goes fleeing in the opposite direction, as far away from Zibby as possible.

In the end, the story becomes more about Jesse figuring himself out, rather than figuring out him and Zibby, and so for better or worse, a sort of offbeat indie romantic comedy becomes a full-blown coming-of-age film. It’s strange and unexpected and different and is the reason I’m so damn confused about how I feel about the script.

You should know me well enough by now to know that, for the most part, I like clean narratives. I like when stories have clear places to go, where we understand the direction of the plot, where we’re staying in the same general vicinity for the majority of the story (unless the genre dictates something else – like a spy or action flick). Liberal Arts doesn’t follow that template. I thought for sure that once we got to the school, we would stay at the school. And when we didn’t, I was confused but still willing to give it a go. However, we’re jumping back and forth between the school and New York so much, and we’re travelling so much and sending so many letters, that at a certain point I began to wonder if it wouldn’t have been a lot easier to go the more traditional route.

Here’s my take on it. You want your characters in the place that produces the most amount of conflict. Two characters 500 miles away? No conflict. Those same characters – who for a number of reasons shouldn’t be together (the main one being their age difference) – stuck on the same campus together? Conflict. Now I can excuse this if the concept of the movie is based around separation (Going The Distance) but the central element of conflict in this case, Jesse’s reluctance to engage in an “inappropriate” relationship, doesn’t work unless the inappropriateness is placed in front of him at all times. If you can’t reach the cookie jar, the question of whether you will isn’t a factor. But if it’s right there at eye level, always there for the taking, then the question of whether you will or won’t becomes a lot more interesting.

I’m so torn up about this script because I absolutely loved the first half. I mean I loved it. The thing with Radnor though is that he’s going to give you something different. He did it in Happy Thank You More Please when he threw a 35 year old man, a kid he found off the street, and a fuck buddy, into an impromptu family. And he does it here. Where you think this is going to be like Point A, where a guy starts dating a much younger girl. But it isn’t. It’s about a guy who’s ABOUT to date a much younger girl, then realizes it’s wrong and backs out of it.

So I guess I should be rewarding Radnor for not falling victim to cliché and obviousness. Yet a part of me feels like I just spent all night flirting with a girl at a bar and then at the end of the night she went home with someone else. 70 pages have been spent setting up this relationship. To rip it out from under our feet like that is at least a little deceitful, right?

Radnor also eschews other suggested Scriptshadow practices, like giving the main character a goal. There is no goal here, and therefore nothing driving the story other than the question of, “Will Jesse and Zibby get together?” On the list of devices that can drive your story, I always rate this one pretty low, because it allows for too much wandering about. Without pursuits, the characters just sort of exist in their day to day lives, so by the time we get around to that question being answered, it’s too late, since we’ve already lost interest. I know of only one movie where that’s the ONLY thing driving the story and it’s still worked, and that’s When Harry Met Sally. So I always suggest avoiding it unless you have some unique way of making it work.

And while I liked Jesse at first, I thought it was interesting that Radnor made him less likable as the script went on (the arc of most characters is the opposite – they start off unlikeable, then we’re given reasons to like them along the way). There’s a whole sequence where Jesse finds out that Zibby’s read Twilight and literally freaks out. He’s so upset about it that he actually chastises her for even contemplating reading the book. It’s somewhat necessary in that it’s the final straw in making him realize that him and Zibby aren’t meant for each other. But I’m not sure Radnor realizes how unlikeable it makes Jesse. I mean, I hate Twilight as much as the next guy. But I think anybody who appreciates art understands that, in the end, taste is in the eye of the beholder. For him to be so cruel to Zibby after finding that book – I don’t know – it just really distanced me from the character.

I know I’m giving a lot of flak to my screenwriter crush Radnor, but I felt he made some choices in the second half that, while different, made the story less satisfying. Still, I loved all the touches, such as accidentally falling asleep on the quad lawn then waking up in the middle of the night (nothing like a random 35 year old man falling asleep in the middle of your college campus). The roommate that keeps popping in at the most inopportune times. The classic college hippy guy who’s always sharing his whacked out but not nearly as deep as he thinks they are philosophies. Radnor continues to have some of my favorite guy-girl dialogue as well. It’s not so much the kind you quote. But it’s fun and honest without being showy, never an easy line to walk.

Anyways, this was a frustrating read for me. I loved parts of it and I hated parts of it. So my final verdict falls somewhere in the middle. Should be interesting to see where it goes since, now that he has a movie under his belt, it will get a lot more attention.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Remember guys. A break-up scene including your main character at the beginning of your script DOES NOT HAVE TO HAPPEN AT A RESTAURANT. In fact, it doesn’t even need to happen at all. Here, in Liberal Arts, the break-up has already happened. And the post-break-up scene takes place at our hero’s apartment, with his ex coming by to get her stuff. I realize we’ve seen this scene before, but not nearly as much as the break-up at restaurant scene that opens 43% of all comedy specs. Please, no more break-up at restaurant scenes starting your movie! You are more original than that. I promise you!

Genre: Action/Sci-fi

Premise: Special Agent David Marsh is recruited by a shadowy corporation to test a new game-changing computer generated amusement park.

About: Amusements is an early script written by AICN contributor Drew McWeeny (aka Moriarty) and his writing partner Scott Swan. While the script didn’t sell, it did help McWeeny and his partner start their careers, which includes a couple of spec sales, as well as writing for the TV series “Masters Of Horror.”

Writer: Drew McWeeny & Scott Swan

Details: 109 pages – undated (This is an early draft of the script. The situations, characters, and plot may change significantly by the time the film is released. This is not a definitive statement about the project, but rather an analysis of this unique draft as it pertains to the craft of screenwriting).

Like many of you, I always enjoyed reading Moriarity’s articles on AICN during the heyday of internet movie news. At a time when there wasn’t an extensive internet film community, he was basically the first (or second, after Harry) guy to give you a nice 20 minute distraction in the middle of the day. Sure, he was a little long-winded, but it’s only because he had a lot of information and passion and opinions packed into that digital cinephile brain of his. Naturally, I was excited to read one of his early screenplays.

First thing I noticed about Amusements? How appropriate the title was. All Amusements wants to do is amuse you. It wants you to have fun. It sounds like these guys sat down and said, “What can we do to make a great summer movie?” And while that approach helps Amusements in places, it hurts it in others. Because while this script is decked to the nines with exciting cinematic set pieces, it doesn’t seem to care about character or story. And that’s what confuses me the most. I know Moriarty cares about character because I’ve heard him preach about it non-stop in review after review. So either this was written early enough in his career where he wasn’t grasping character yet, or he and his partner made the decision early on: This is a fun action flick. Forget character development.

Special Agent David Marsh specializes in high-tech crime assessment technology. He goes into Matrix-like virtual computer environments, makes sure all the ones and zeroes are aligned properly, then gets out. So it shouldn’t be surprising that two mysterious figures approach him and want him to assess the granddaddy of all digital environments, “The Park,” an amusement park that makes Disney World look like a North Korean jungle gym.

The Park was founded by a mysterious man named Alex Parker (Parker’s current whereabouts are unknown), who had a dream to make the perfect amusement park, one that really could make all your dreams come true. Since it’s all digital, you could go anywhere, from turn of the 20th century South Africa to a nearby alien star. I’m still a little unclear on why David is called to The Park, but I think it’s to make sure the technology has no holes.

Anyway, David brings his wife to the park to add some pleasure to what would otherwise be business, and meets a group of other park members who will be joining them in their group. And from nearly the second they get there, the party begins.

At first they hop on a South African Safari train and within minutes are attacked by a silverback gorilla and some not so friendly British soldiers. From there, they visit a zero-G restaurant. Then head into the Bayou where they meet a high priestess and a lot of zombies. And finally head into space to kill off some aliens.

Somewhere along the way, David realizes that Parker has embedded himself into the mainframe of the Park’s computer, and is planning to live there forever. A spooky ass dude named Samuel who was killed in the park tries to tell David that there are more like him. That something sinister has been going on. And so the script ends up with David taking on Parker one on one, to eliminate him and end all this park madness.

I don’t know Moriarty. But I’m going to guess that if he re-read this today, he’d be a little embarrassed. I mean, the idea itself is pretty clever. He and his partner have created a premise that basically allows them to add whatever their imagination can come up with, and it will make sense! Aliens? No problem. Zombies. Check. Heaven? You got it.

The problem is that the story is so thin and the character development so non-existent, that it’s hard to get emotionally involved in any of it. These are two things that are most responsible for adding depth to a script – three-dimensional characters and a good story – but Drew and Scott seem more intent on stringing together a bunch of set pieces. I’ll say it again, the set pieces are fun. And we’ve definitely reached a point in movies where people don’t make interesting set pieces anymore, so I’m not going to short-change these additions. But I guess what’s so confusing to me is that they don’t even attempt to dig into the characters.

Actually, let me back up a little. They didn’t add any depth to our heroes. They did put some thought into our villain, Alex Parker. Parker, a sort of deranged version of Walt Disney, had a troubled childhood, lots of people doubted he could build this park, and he’s a self-made man. So there is some legitimate backstory there. The problem is we’ve seen this character before. In fact, the KFC Colonel ruined any chance of this character working when the Wachowskis made a joke of him in their final Matrix film. We have to keep in mind, of course, that this was written around 2002, and that it wasn’t AS cliché as it would be today. But still, there was something very non-threatening about Parker. I never feared him. In fact, he seemed quite honorable, making a deal with David about leaving the park. Compound this with the fact that I was never sure why he brought David there in the first place, and I just couldn’t get on board with the guy.

And while I liked the fact that Drew and Scott just flung us right into the story – I mean when we get to the park, we’re on that South African train within a few pages – I did think that the story needed a more gradual build-up to the park turning on them. Even though it would’ve taken longer, establishing the park as safe and secure and trustworthy would’ve made the moment when it turned on them all the more impactful. Take Jurassic Park for example. When we get there, we probably spend a good 20 minutes of feeling like everything is safe and trustworthy before it all starts to go bad.

Complicating this is the uncertainty behind the rules of the park. Can our heroes be hurt? Is the park trying to hurt them? This train ride with everyone attacking them seems really intense, but if all that happens when they die is they’re sent back to their room, then how exciting is it really? Having said that, this was the same issue I had with Avatar. If our hero gets killed in his Avatar body, nothing happens to him. He just wakes up back at the lab, which makes all his 5 mile high tree climbing and dragon-rousing a lot less exciting when you think about it. And that movie went on to gross 2 billion dollars, so what do I know?

What I get from Amusements is that these guys love writing action. You can smell it in every line. The problem is, it’s all fan-boy and no heart. I would’ve liked more character depth outside of the villain, and a story with a more clearly defined goal (I’m still not sure why they go to the park in the first place). And some clear stakes! If you liked movies like Westworld and the The Matrix, you may want to check this out (it can be found on the net). But all in all, there’s not enough meat on the bone here.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: A couple of things. When you try to please everybody, you please nobody. I think these guys were trying to please fanboys, studio execs, audiences, everyone, and in the process they forgot to please themselves – always the most important audience member to focus on when telling your story. Also, you have to have an interesting main character. David is way too stock. There’s nothing memorable or unique about him. Even when action is the real star of the movie (ID4), your main character has to have something going on with him that makes him memorable.