Genre: Drama/Zombie

Premise: A high school girl has been contaminated with the zombie virus. However, in this treatment of the zombie dilemma, the change takes months to complete.

About: Zombie spec script “Maggie” drummed up a lot of excitement a few weeks back when a bidding war erupted for the original screenplay and was eventually won by Wanted director, Timur Bekmambetov, for mid six figures. For whatever reason, something happened and the spec went back on the market, where I assume it will be picked up by someone else soon. A big reason for the interest seems to be that the genre project would be cheap to produce (with an under 5 million dollar price tag). Deadline.com reports that the writer, John Scott 3, works with the Chandra X-Ray Observatory for NASA, which takes photos of X-ray photons in deep space. Someone will have to confirm this for me, but I think the script also won the Page Screenwriting Contest.

Writer: John Scott 3

Details: 101 pages – undated (This is an early draft of the script. The situations, characters, and plot may change significantly by the time the film is released. This is not a definitive statement about the project, but rather an analysis of this unique draft as it pertains to the craft of screenwriting).

Maggie’s been burning up the internet ever since it became a hotly sought after spec script a few weeks ago. Speaking to those who have read it, I can tell you that the reaction has been all over the map. Some liked it and some absolutely hated it. With Hollywood firmly committed to making zombies the next vampires, you can say that the zombie trend is here to stay. And right away, before even reading Maggie, I had a pretty good idea why this zombie flick sold.

Once again, a writer has taken a tired genre and found a fresh angle on it. I guarantee we’ve never seen a zombie flick about a six month incubation period before (or is it six weeks? – wasn’t clear on that). Nor have we seen one where the main characters are never in any danger of, well, being attacked by zombies. This, of course, is going to be why the opinions on this one run the gamut. People are going to expect certain things from this script that they’re never going to get. And that’s going to piss them off. The question is, will the ones who survive that knee-jerk reaction fall in love with what is essentially a slow-moving allegory for cancer?

The world’s been overrun by zombies. We’re talking hundreds of millions, maybe even billions of zombies. Luckily, the powers that be have finally gotten things under control and, at least for now, the zombie issue has been contained.

The strange thing about this zombie virus, however, is that you don’t turn into a zombie right away. Instead it’s a gradual change, about six months, and this allows those who are infected to go back to their homes and live with their families until the big switch arrives.

16 year old Maggie is one of those victims. She ran out into the world unprotected and got bit by one of them. Now, she’s living in her rural home with her overly emotional father Wade, and her stepmother, Caroline. She’s got a couple of siblings as well, but they’ve been moved out of the house until Maggie, you know, officially becomes a zombie.

The story centers mainly around Maggie’s relationship with her father. Naturally, he feels helpless that he can’t save his little girl, and therefore every single moment between them becomes precious.

One of the problems people have been having with this script is the lack of story density, and I can’t say I disagree with them. There simply isn’t a lot going on here. While there is a ticking time bomb (her switch), there’s no real goal for any of the characters, resulting in a cast of passive characters. As many professional writers will attest to in their work-up to becoming professionals, one of the most important lessons they learned was to stay away from passive main characters. If nobody’s doing anything, it’s just a bunch of characters sitting around talking to each other, complaining about things, trying to make it through the day. And it’s almost impossible to make that interesting over an extended period of time. Indeed, Maggie suffers from characters who don’t have much to do, and therefore each scene is either a repeat of an earlier one or a slightly different variation of it (i.e. Maggie vents her frustration about being sick half a dozen times).

That’s not to say none of it works. It’s a sad circumstance for sure and the theme of impending death – our fear of it, the world’s fear of it, the way people distance themselves from it, the way family is forced to deal with it – is powerful and heartbreaking stuff. Maggie essentially has cancer of the zombie, and her and her family’s unwillingness to accept this feels like one of millions of cases of the same scenario playing out around the world as we speak.

But I think my problem with Maggie was that it didn’t give us anything that we weren’t expecting. For an idea that’s so unique, you’d want the scenes and the twists and the characters to all carry that same uniqueness. For example, I was thinking, ‘I hope there’s not a bunch of overly dramatic scenes where the characters complain about God,’ and sure enough, there were a bunch of overly dramatic scenes where characters complained about God. We’ve seen that before. We know it’s coming. In the book for The Lovely Bones (the book, not the movie), the daughter is raped and killed. They could’ve easily gone down depression alley with the characters slumped in dark corners complaining about how life isn’t fair. Instead they bring in the drunk grandmother character who cheers everyone up. It’s not where we expected it to go, and therefore it was refreshing.

Also, I would’ve looked to have added waaaaaay more conflict to the story. For example, why make it so easy to keep Maggie at the house? What if, instead, at the beginning of the movie, the government, fearing a recent uptick of zombies, declares home incubation illegal, and demands that all the infected be brought in? Imagine the tension you could create from officials showing up at the house and asking where Maggie was. Imagine Wade hiding Maggie and the officials looking through the house.

Also, all the characters in Maggie treat the title character the same way. They’re worried for her and feel sorry for her. I’m sorry but that’s boring. You have a stepmother living in this house! Let’s utilize her. What if she doesn’t agree with Wade about Maggie staying here? What if she wants Maggie out? In conjunction with the change I just mentioned, what if the step-mom is considering selling Maggie out? Telling the officials she lives here? The point is, we needed some sort of conflict inside the house, and we weren’t getting it.

There were other things that concerned me as well. There were too many monologues. Too much clumsy exposition. There’s a point, for example, where Wade lays out his daughter’s entire history on the phone to a bank manager. It’s long and awkward and not a very inventive way of conveying information (although I did like how the bank’s impending repossession of the house upped the stakes and made things more difficult for the family).

I’d be interested in a rewrite here. There needs to be less repetition in the story, more conflict, not so much melodrama, more twists and turns, more variety in the emotions (everyone’s so bleak!), more story density, and probably more humor to relieve the tension. There’s a good message here, but the wrapping is too saccharine and monotonous.

There were some good things though. I thought the script became more interesting as it went on. In particular, when we start to see Maggie craving live meat and not able to control herself around the family. Watching her father’s denial was beyond heartbreaking, especially as she neared death – easily the script’s best moment. But like I mentioned, the journey to get to that point was too predictable and too maudlin. Will be interesting to see where the rewrites take this.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Someone just brought this up in the comments section of “Great Hope Springs.” And I think it’s a great note. Every script needs emotional peaks and valleys. We need to be brought way up then we need to be brought way down. You need to run the gamut of emotions on us. If it’s just one emotion all the way through, it’ll feel one-dimensional and stale. Bring your characters and your audience through emotional peaks and valleys!

Genre: Action

Premise: A man with an unusual job gets stuck trying to escape from a secret black ops prison.

About: Mixed rumors on this one. Bruce Willis is supposedly attached. But Arnold Schwarzeneggar is also said to have taken an interest in Exit Plan. Either way, it looks like Antoine Fuqua is going to direct. Summit bought up the spec from Miles Chapman back in 2008, whose previous credits include the straight-to-video “Road House 2.” They brought in a slightly hotter writer, Jason Keller, who wrote Tarsem Singh’s upcoming Snow White picture, “The Brothers Grimm: Snow White,” to do the rewrite, but then went back to original writer Chapman. What’s happened in the 2 years since is anyone’s guess.

Writer: Miles Chapman (with earlier revisions by Jason Keller)

Details: 102 pages – 1/06/09 draft (This is an early draft of the script. The situations, characters, and plot may change significantly by the time the film is released. This is not a definitive statement about the project, but rather an analysis of this unique draft as it pertains to the craft of screenwriting).

Sandwiched in between a couple of slooooowwww screenplays, we’ve got ourselves a good old fashioned high-concept escape spec today. The question, however, is the same as whenever I read a high concept screenplay. Does the execution live up to the idea? The inclusion of Bruce Willis did not instill confidence. The man seems to be on his way out, and not just because he’s an asshole to everyone he comes in contact with, but because he just doesn’t seem to give a shit about movies anymore. I’m not sure I’d be much different if I’d starred in a hundred films. I mean, who cares if my last one was any good? As long as I get my check baby! The point is, his attachment is usually a sign that 20 other actors have passed, and that’s never a ringing endorsement for the material.

(Spoilers follow) Exit Plan starts in a top level prison with a felon named Ray Breslin, a hard-ass with an attitude problem – hey, this is actually sounding like it’d be perfect for Willis! Anyway, Breslin appears to be a little brighter than the rest of the rats in this cage, and we soon figure out that he’s planning an escape. After getting himself thrown into isolation, he cleverly creates a fire raid which allows him to sneak out of the prison as one of the firefighters.

Cut to Breslin in an office – receiving a check. Ahhhh, now we get it. Breslin does this for a living. He gets hired to go into prisons under aliases and design an escape meant to expose security flaws. And Ray does the job every single time.

Suffice it to say, he wants a challenge. But his handlers remind him that he’s broken out of every major prison in the U.S. There aren’t any challenges left. What about internationally, he asks. And that’s where things get interesting. There’s a mysterious businessman who wants to purchase Breslin’s services for a secret prison, one that’s so far off the map and so top secret, that he won’t know of its location until he gets there. Breslin can’t sign on the dotted line fast enough.

Big mistake.

After being drugged and thrown into the jail, Breslin realizes that this is unlike any jail he’s ever seen. Cells are stacked on top of each other and see through, with a ring-shaped platform allowing guards to see everyone at all times. Escape demands privacy. Here, there is none. But it gets worse. The warden, a bloodless man named Roman Steffes, doesn’t seem to know who Breslin is. Which means Breslin’s failsafe, being able to tell the warden his real identity, is off the table. And the topper? Breslin finds building schematics based on his OWN STUDY OF PRISONS. This prison was built specifically to withstand every weakness Breslin has ever found in a prison. Uh oh.

Breslin’s only ally is a quick-witted man name Church, who rightfully thinks Breslin’s crazy for even mentioning escape. It’s impossible. Plus Church has his own set of problems. He seems to know one of the most notorious terrorists in the world, and therefore is being watched 24/7 by the guards. How will Breslin ever break out of here, much less with this attention-grabbing buddy of his? And where is “here” anyway?

Yesterday was all about the characters. The inner journey is what drove the story. Here, it’s the plot that’s the star. It’s the twists and turns and surprises and reversals that keep you reading, and boy are there a couple of doozys. I’ve read a lot of scripts, so it takes a lot to trick me or make me wonder what’s going to happen next. And while I definitely had some suspicions, I was genuinely surprised a few times. There’s a late 3rd act reveal in particular that I did not see coming, and it was a good one.

What’s cool about Exit Plan though is that it still cares about its characters. They might not be as well-rounded as, say, the characters in The Godfather, but Breslin is someone with a real past, believable motivation, and crippling flaws. Breslin’s parents were murdered when he was younger and the killers were able to escape prison. Breslin’s set on the bad guys never finding a way out again. And that’s why he does what he does. It’s a great reminder that you can come up with a cool idea for a movie, but you still have to make the hero interesting enough that some bankable star will want to play him.

There’s a lot of writing skill on display here for an action flick actually. I took note of this towards the end, as in every action thriller, you want to up the stakes to draw out the most amount of tension and excitement possible. If the stakes and the time frame are the same as what they were in the second act, then there’s no real difference between then and now, and the third act fizzles. This is kind of what happened yesterday in Great Hope Springs. So in the third act of Exit Plan, Roman meets with Breslin and gives him 24 hours to get the location of Church’s terrorist buddy, or he’s going to keep Breslin in this prison on 24 hour surveillance for the rest of his life. From that moment on, the story takes on a considerable amount of urgency. And it’s all because the writer knew he had to up the stakes in the third act.

Another great thing about the script is just how impossible it makes Breslin’s mission seem. Again, this is what writing action-thrillers is about. You want to make the hero’s goal seem as impossible as you can so it looks like there’s no way to succeed. You do that and we’ll be at the edge of our seats the whole time. In Exit Plan, there’s never any privacy for the prisoners. The warden doesn’t care about Breslin’s real identity. The prison was built specifically to hold him in. The location makes an escape impossible. I mean, we really have no idea how he’s going to pull this off, and that’s what makes each step he takes so dramatically compelling.

However, I did have a few issues. First of all – and I find this to be a problem in a lot of “escape” films/TV shows, not just this one – not everything Breslin does is as clever as it needs to be to sell his genius. For example, he uses a heat reflection pad to de-oxidize screws to escape through some floor panels. I have no idea if this is possible in real life or not, but I do know that to the average audience member, it sounds made up. This is why Shawshank is the best prison movie ever made. The escape was not only clever, but it was simple. We just “got it.” I’m not sure that de-iodizing screws is going to do anything but confuse an audience. And there were a few other less than stellar choices in the steps he took to escape as well. So I’m hoping they came up with better choices in the rewrites.

On top of that, Chapman may have dug himself into too deep of a hole. Like I said above, it’s important to make things as impossible as you can for your hero. But only if you can write yourself out of those impossibilities in a believable way. There were some things that I had a hard time buying. For example, they know Breslin’s dangerous. They know Church is dangerous. Why not just assign two guards to watch both of them the entire time? They seemed to have the manpower to do it, and it was definitely necessary with how dangerous they knew them to be, so the fact that they didn’t and Breslin was constantly sneaking around the prison was hard to buy.

But overall, there was a lot more good here than bad. I’ve always liked these “get paid to go in and find faults in a company” films and doing it for a prison seemed like a logical extension of the idea. The added hook of placing Breslin in an impossible-to-escape-from prison where his secret status no longer mattered, was likewise a nice twist. Plot-wise, this was perfectly paced. And I loved the unexpected twist at the end. Easily one of the better “escape” scripts I’ve read in a long time. Hey, what do you know? Two really good scripts in a row this week!

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: The easier your hero’s journey is, the more boring your movie will be. Your job, as a writer, is to make your main character achieving his goal as difficult as possible. Doesn’t matter if it’s an action movie or a romantic comedy. MTDD! Make things difficult dammit! (I promise this will be the last acronym I use for “What I Learned”).

Genre: Drama

Premise: A woman forces her husband into couples therapy to save their marriage.

About: This script originally made the 2008 Black List under the title, “Untitled Vanessa Taylor Project.” It more recently gained the “Great Hope Springs” title when it secured heavyweights Steve Carell and Meryl Streep in the cast. Actors rumored to be playing the husband are James Gandolfini and Tommy Lee Jones, both of whom I think are spot-on choices who would do a great job – Jones in particular would be awesome. The movie was originally a directing vehicle for Mike Nichols, but is now being headed up by David Frankel, who’s become hot after having two surprise hits in a row: “The Devil Wears Prada” and “Marley and Me.”

Writer: Vanessa Taylor

Details: 108 pages – June 20, 2008 Black List draft (This is an early draft of the script. The situations, characters, and plot may change significantly by the time the film is released. This is not a definitive statement about the project, but rather an analysis of this unique draft as it pertains to the craft of screenwriting).

Okay, we have two slow-moving stories this week and I didn’t like one of them. So I want to preface this by explaining why I liked Great Hope Springs a lot more than that Wednesday review. Remember, the biggest influence on a reader liking a screenplay is subject matter. If they’re interested in the subject matter, they’re miles more likely to be interested in that film/script. And this subject matter is right up my alley.

I’m fascinated by marriage. I think we’re at a point in society (at least here in the U.S.) where the institution of marriage is on its way out. Not only are more people getting divorced. But the divorce rate is causing more people to fear marriage, to not get involved in the first place. And I think that’s the result of a lot of things. But the biggest thing is that people don’t persevere anymore. When something goes bad, they don’t try and fix it. They just walk away. And without trying to sound too corny, I believe that the people who stand up and fight for their marriage are some of the last heroes out there, because it’s so much easier to pack it up and move on. And that’s exactly what today’s script is about. It’s about a woman trying to save her marriage.

52 year old Maeve Soames (“sweet and sexless”) doesn’t exactly have a wonderful marriage. She’s got two grown kids, but they’ve both moved out, and that leaves just her and Arnold, her hard-nosed husband, the kind of man who ends every day telling you how pissed he is about some client at work. Not exactly a bright bowl of cherries. If you have any questions about where this marriage currently stands, the fact that the two sleep in different bedrooms might give you a clue.

That’s not to say they don’t like each other. They just don’t see each other as emotional sexual human beings anymore. Their relationship has turned into a second business, one you try to manage and maintain but are ultimately emotionally absent from. And Maeve is sick of it. So sick, in fact, that she lays down an ultimatum. Either they go to an intensive marriage therapy doctor in Wyoming or she’s leaving. Arnold thinks this is a classic “wife bluff,” something you endure, wait for them to calm down, then move on from. But he quickly realizes she’s very serious, and therefore has no choice but to join her on the trip.

Cut to a tiny town in the middle of nowhere that’s looking a lot more like a prison to Arnold than the picturesque headquarters of a famous marriage counselor. Dr. Bernie Feld plays the unique role of both hero and villain in the story – hero to Maeve and villain to Arnold. Arnold’s hatred for this man and his practice stems mostly from the ridiculous $4000 price tag he’s set on this week. As he says to Maeve, “That could’ve been a new roof.”

Almost immediately, we jump into therapy, and this is where the meat of Great Hope Springs is. In every movie idea you come up with, you’re looking for areas that are going to provide the most amount of conflict, where the main source of resistance is going to come from. Here, it’s these sessions, specifically the fact that Maeve desperately wants to be here and Arnold desperately doesn’t.

Not only is Arnold unable to open up, but he believes therapy to be a crock of shit, so the sessions are packed with tension both from the marriage stuff AND from him not wanting to be here. So intense are these early sessions, you get the feeling that at any moment, the room could explode. At the core of the problem is that Arnold believes the marriage is fine. That sleeping in different rooms, not talking about anything meaningful, never doing anything fun or romantic, is perfectly okay. As long as you put in the time (the marriage is over 30 years old), then you’re entitled to coast.

So he’s shocked and angered that Maeve doesn’t feel the same way, not realizing that this is the main issue – that they don’t talk enough for the other to even know that there’s something wrong. But with Maeve now making it clear that if he doesn’t change, she’s out the door, Arnold realizes that he better at least try and give Dr. Feld a chance, or the one mainstay in his life could be gone forever.

One of the cool things I noticed about Great Hope Springs is that while it has that “indie” character piece feel, the structure is textbook. We have a clear goal – save the marriage. We have a ticking time bomb – one week. And the stakes are sky high – a 30 year old marriage is on the line.

But like I said, what really makes Great Hope Springs fly is the conflict, or more appropriately, Arnold’s resistance to change. Remember that. If you don’t have at least one character in your screenplay who’s resistant to change, there’s a good chance you’re not getting the most emotional punch out of your story.

And the less likely it appears that that character will be willing to change? The more compelling it will be. That’s the case with Arnold here. He hates admitting he’s wrong, he hates therapy, he hates this therapist, he hates that Maeve’s making him do this, he hates this town. We’re thinking, “There’s no way in hell this guy is going to change his mind.”

Another thing I like about the structure is that Taylor uses the therapy sessions as pillars to keep the story moving. Each session is packed with conflict, so they’re always interesting. But then you also have Feld giving them a goal to try before the next session (i.e. go have sex). That way, once we leave the session, we’re interested in whether they can achieve this goal, and we’re also looking forward to what challenge will be presented in the next session.

Another thing to note about Great Hope Springs is the unique way that therapy allows you to do things with your characters that you wouldn’t normally be able to do. Most scripts, especially emotional character-driven scripts like this, thrive on subtext, the unspoken words that live between the words that the characters are actually saying. But when you put a character in therapy, there’s no more subtext. Essentially, you’re allowing the characters to do what you, as a screenwriter, are told never to let them do, which is to speak “on the nose,” – say exactly what’s on their mind. But the reason that it works is because it’s motivated. They HAVE to say how they feel. They have no other choice. So if you’re looking for that opportunity to have your characters get right to the point, throwing them into a therapy session might be a good idea.

I do have a few problems with Great Hope Springs though. First, the last 35 pages don’t live up to the rest of the script. What I liked about this story was that the therapy kept building, kept providing new challenges every time they came in. But towards the end, once we get to the sex-related stuff, the therapy kind of becomes redundant. We’re battling the same problem over and over again and after awhile it just became stale. This is followed by a lackluster unimaginative ending. In fact, it felt so tacked on that I wondered if it wasn’t a placeholder ending.

Finally, I wish there was more humor here. And with Steve Carell coming on, I’m guessing that’s a direction they took in subsequent drafts. Which is a good idea. Because while the conflict in this script is excellent, there aren’t enough laughs to release all that tension. If they fix these few issues, this could be a superb character study, and one of the better movies about marriage ever made.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Somebody has to change in your story. It may not be the hero. It may not even be the love interest. But change – or the attempt to change – is the key emotional component that drives an audience’s interest, so at least one character should experience it. And the more resistant they are to that change, the more compelling their journey tends to be.

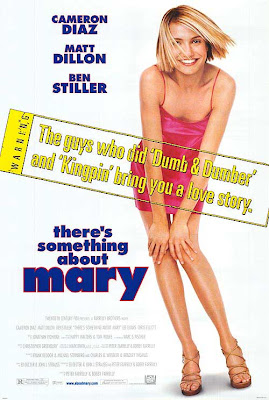

It’s Comedy Theme Week everyone. For a detailed rundown of what that means, head back to Monday’s post, where you’ll get a glimpse of our first review, Dumb and Dumber. Tuesday, I took on the best sports comedy ever (yeah, I said it), Happy Gilmore. Wednesday was Grouuuuuundhog Day. Thursday, Wedding Crashers. And for our final film of the week, one of my favorite comedies ever, There’s Something About Mary!

Genre: Comedy

Premise: 15 years after a horrifying prom night accident, a man decides to take a second shot at the girl he fell in love with. Only problem is every other man in the world wants her too.

About: The movie that propelled cinema into a decade of gross-out humor (some of which is still going on today), There’s Something About Mary became a sleeper hit back in 1998, bringing in 176 million dollars at the box office. In one of the best known gags in the film, where Mary erroneously mistakes Ted’s semen for hair gel, Cameron Diaz was said to have fought the gag ferociously. Her argument (which was rather sound if you think about it) was that a woman on a date would be checking herself constantly, and therefore would never have her hair like that. The Farrelly’s finally convinced her to give it a shot, and we subsequently got one of the most memorable moments in film history.

Writers: Peter and Bobby Farrelly

There’s Something About Mary is in my top 3 comedies of all time. The structure, much like the Farrelly’s other movie I reviewed this week, Dumb and Dumber, is all over the place. But the reason this film makes you laugh is because it has some of the best comedy set pieces ever written. And it’s a testament to how finicky comedy is, because I’ve seen the Farrelly’s create countless set pieces since then that just weren’t funny. And that’s one of the reasons I wanted to revisit this classic. I wanted to figure out what made this one different.

First, the structure. Again. Three words. “What the hell?” This is a really oddly-structured film. The movie places its first act in the past, establishing Ted and Mary’s relationship as teenagers. It then spends its entire second act with the two apart. I want you to think about that for a second. A romantic comedy (which is what this essentially is) keeps its two leads apart for the entire middle portion of the movie. What the hell?

It gets weirder. We started off with Ted as our main character. But the middle act actually switches over and makes Mary the main character, occasionally giving the spotlight to Healy (Matt Dillon’s private detective villain). So the entire middle act is dedicated to a relationship which isn’t the main relationship in the movie. The main relationship, Ted and Mary, doesn’t get kickstarted again until the final act! That’s when Ted arrives in Florida and makes his move on Mary. The third act then becomes its own little romantic comedy, with the traditional, “Guy gets girl, guy loses girl, guy gets girl back.” With montages and everything!

So why does it still work? Well, I think I know. All of the guy characters in this movie have incredibly strong goals: “To get Mary.” That drive means that it doesn’t matter whose story we jump to, because when we get there, that storyline will have intense forward momentum driven by that character’s pursuit of that goal (Mary). Also, through it all, the story’s driven by our ultimate wish, to see Ted get Mary. In fact, outside of When Harry Met Sally, I don’t know of a comedy or romantic comedy where you want the two main characters to get together as much as this one.

And I think that’s a huge part of why the movie works. There’s Something About Mary spends the first 90 minutes of its running time building up Ted’s attempt to get Mary. Remember how yesterday I said the reason Wedding Crashers was weak was because the stakes were low? Well here, the stakes are as high as they can possibly be. The reason we care so much in the last 30 minutes is because we’ve just spent the entire movie watching Ted go through hell and back to get to Mary. This build-up is what makes their scenes together so captivating. Because they’re packed with the tension of “Will this work out? Does he finally have her?” Go back and watch that scene where Ted first meets Mary again. In that 3 second moment after Mary responds, “Didn’t we just do that?” to Ted’s asking her if she wants to get some coffee and catch up, I can’t remember a time in movies when my heart sank that much. And it’s all due to the buildup of stakes.

Attention to stakes is also the key to one of the most famous comedy scenes ever, when Ted gets his balls stuck in a zipper. The reason this scene works so well is not because, “Wowza! His nuts are stuck in a zipper!” It works because for the last 20 minutes, the writers have built up that this is the single most important moment in Ted’s life. Somehow the nerdiest kid in school has pulled off the impossible – he’s taking the prettiest girl in school to the prom (stakes)! We are on pins and needles begging that this works out. So when it starts to backfire, and when that fateful zipper moment comes, and we’re hoping and praying he somehow fixes it in time to still go to prom. When it doesn’t? And the situation continues to get worse instead? It breaks our heart. Because we know this is it. You don’t get a second chance to take the prettiest girl in school to prom.

The scene also does double duty, creating a key residual effect. That terrible situation he went through? That losing of the chance to go out with the most popular girl in school? It makes Ted the single most sympathetic character in the world. I mean we’ll go anywhere with this guy after that. And so when we learn that he’s going to take another shot at Mary, even if he’s going about it creepily and hiring a private investigator? We don’t care. Because we believe he deserves that shot. And whereas yesterday the goal of getting some random girl at a wedding made Wedding Crashers’ driving force weak, the pursuit of the perfect girl who you lost out on when you were in high school because of a freak accident…that goal is about as strong as they come.

I want you to think about that because it’s an important screenwriting lesson to remember. What happens if Owen Wilson loses that girl? Let’s see. He loses out on a girl he’s known for all of 24 hours. No offense but: BIG FUCKING DEAL. He’ll get over it. But with Ted, this is the girl he’s spent every day for the last 15 years thinking about. It’s personal. There’s history there. If he loses this girl, you feel there’s a good chance it will destroy him for the rest of his life.

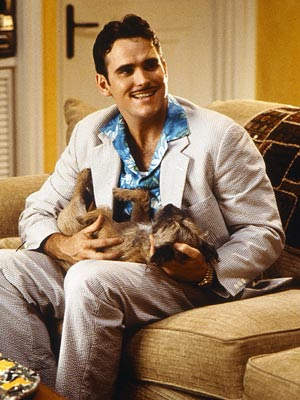

The Farrelly’s, like Happy Gilmore, have also created a great villain. Unlike the one-dimensional forgettable villain in Wedding Crashers, Tad Healy has a ton going on. He’s smart. He’s funny. He’s slimy. He’s good at what he does. This is what I mean when I say, “Add some dimension to your villain.” Again, you could’ve just made him a great big asshole. But Healy is much more than that, which is why his character is so memorable.

Another thing I like about the Farrelly’s comedy is they always ask the question, “How can we make this worse for the character?” And when you do that, you usually end up with something funnier. So in the scene where Healy drugs the dog so it likes him and impresses Mary, they say, “How can I make this worse for Healy?” Well, what if the dog died? So now the dog’s dead. And now Healy has to do the whole “CPR” bit on the dog and bring it back to life before the women come back in the room. You see this device being used again and again throughout the movie, especially on Ted, and it’s a big reason for all the hilarious set pieces.

But I think the thing that sticks out to me most when breaking down this film, is how wonky that structure is. The Farrellys have really weird structures to their films. Just like Dumb and Dumber, we have our heroes starting in one place, driving to another, and then beginning a relationship in the final act. But Mary is even more complicated, since the second character (Healy) is our villain, and isn’t with Ted on his trip. Therefore you have this cross-cutting storyline going on in the second act where we’re jumping back and forth between Ted’s journey and Healy and Mary’s courting. I have to admit, it’s different from any comedy plot I’ve read, and I get the impression that Peter and Bobby haven’t ever looked at a manual on how to structure a screenplay. This is why Dumb and Dumber and Mary feel so fresh. They don’t go how you think they’re going to go. However, before you jump on that bandwagon, it’s important to note that this seems to hurt them just as much as it’s helped them. They have some dreadfully unfunny movies in their vault, many of which peter out near the end (Stuck On You, Me Myself and Irene, and The Heartbreak Kid), and a lot of that is structure-related.

Lots of other things to take away from this movie. I didn’t get the chance to show, once again, how much effort the Farrellys put into making you love their hero (he befriends the retarded brother. He wants to help out Mary even after learning she’s 250 pounds and in a wheelchair), but I think it’s safe to say that a big part of the formula for their success is making sure you love and root for their protagonist. I also thought this was one of the few “romantic comedies” to create a fully rounded female character. She was maybe a wee bit on the wish-fulfillment side (she loves sports, likes to hang with the guys, doesn’t care about looks) but Mary is definitely different from every other romantic comedy lead female you’ve seen. There’s Something About Mary is one of those few screenplays that takes chances, breaks the rules, and those changes actually end up making the final product better. I can’t tell you if this happened on purpose or by accident. All I can tell you is that it worked.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[x] genius

What I learned: KYFC! Know your fucking characters! I’ve been encountering this a lot lately in the amateur screenplays I’ve been reading. Writers aren’t thinking about their characters! They don’t know what their character does for a living, what their passion is, what their dreams are, what their vices are, what their bad habits are, what they like in the opposite sex, what their education is, what state they grew up in. I used to be of the opinion that this stuff didn’t matter. I’ve done a 180 on that and let me tell you why. I’ve realized that a lot of boring dialogue comes from the fact that the writer doesn’t know enough about the character who’s speaking that dialogue. When you don’t know that person, you give them generic lines. Let me give you an example. There’s a moment where Mary’s roommate, the old woman, asks her if Matt Dillon, who she’s going on a date with, is cute. She replies, “He’s no Steve Young.” Now this is by no means an earth-shattering line of dialogue. However, it’s a line of dialogue that could only come from Mary herself. It’s a line of dialogue that tells us a lot about who Mary is (she likes football – which is also established earlier in the screenplay when she’s telling Ted about her love for the 49ers). Without knowing that Mary is a woman who loves football and the 49ers, we may have heard a more generic response such as: “He’s all right I guess.” That’s a line that anybody in the world could’ve said. It’s generic and uninteresting. And the less you know about your characters, the more lines LIKE THAT are going to come out of your characters’ mouths. Add enough of them up, combined with enough lines from other characters who you don’t know well, and the more non-specific lacking-of-insight boring generic dialogue you’re going to get. So people, please: KYFC!

What I learned from Comedy Week: In 4 out of 5 of this week’s comedies, the writers went out of their way to make their characters sympathetic. Loving the characters may not be a requirement (you don’t love Phil in Groundhog Day), but in comedies, it helps a lot. Also, in 4 out of 5 of the comedies, the characters had incredibly strong goals. I can’t stress this enough. The more your hero wants to achieve his goal, and the bigger and more important that goal is, the better your script is going to be. It’s no coincidence that the script with the weakest central goal (Wedding Crashers) was also the weakest of the comedies. Outside of that, the rules are fairly wide open. Just try to keep the stakes up, not just for the film but for the set pieces and individual scenes as well. Add multiple dimensions to your villain to make him memorable. And make sure your concept is funny to begin with! Any other trends you guys caught from this week’s entries, please include in the comments section! :)

It’s Comedy Theme Week everyone. For a detailed rundown of what that means, head back to Monday’s post, where you’ll get a glimpse of our first review, Dumb and Dumber. Tuesday, I took on the best sports comedy ever (yeah, I said it), Happy Gilmore. Wednesday was Grouuuuuundhog Day. And today, grab your invites cause it’s time to crash some weddings.

Genre: Comedy

Premise: Two friends who live their lives to crash weddings get in over their heads when one of them falls in love with a bridesmaid.

About: Steve Faber and Bob Fisher wrote Wedding Crashers, yet strangely haven’t had a produced credit since (the film came out in 2005). They have sold a couple of specs though, including the Scriptshadow reviewed, “We’re The Millers,” about a fake family trying to smuggle drugs across the Mexican border. While Faber and Fisher obviously wrote the script, Vaughn and Wilson are said to have rewritten a lot of their own dialogue. The film made 209 million dollars in the U.S., which was a total surprise to New Line, who would’ve been happy with a take of 75 (the movie cost 40 million).

Writers: Steve Faber and Bob Fisher

So I sent an e-mail out to my most loyal readers asking them to pick between Wedding Crashers and Office Space for the final comedy pick of the week (there’s one more tomorrow, but I already had that one in place). I was kind of shocked when Wedding Crashers received just as many votes as Office Space, a movie that’s in my Top 3 comedies of all time. I thought Crashers was amusing but I didn’t think it was hilarious. When the final tally came in, Office Space actually beat Crashers by a couple of votes, but I decided to review Wedding Crashers anyway. Why? Because I think Crashers represents the beginning of a paradigm shift in the way comedies were marketed and, by association, written. Wedding Crashers decided to do away with the high concept, and make the concept the title itself. Wedding Crashers. Knocked Up

. The Break-Up

. 40 Year Old Virgin

. Forgetting Sarah Marshall

. The shorter time in which you could convey what your story was about, the easier it was to sell. So what’s shorter than stuffing your concept into the title? Now, hooks like weathermen stuck in time loops and hockey players forced onto the golf tour were unnecessary.

How do I feel about this? Well, I find it funny. You’re essentially dressing up what 15 years ago would’ve been considered “low-concept” and saying it’s the “new high concept!” Who needs a plot? Just throw people into a situation! Guys! Crashing weddings! Genius! I’m not being totally fair here. The truth is, in the right hands, movies like this can work. The idea of crashing weddings is funny. It’s just a little sad to see the more intricate comedy ideas of the past being deep-sixed as a result.

Now my memory of this film is so-so. I only saw it the one time in the theater. But I remember thinking…ehhh, not bad but nothing special. So I was curious to see why I felt that way. As the first 30 minutes unfolded, the answer revealed itself. Wedding Crashers’ plot is slow and plodding. Instead of the hardline goals of the previous three comedies (return the suitcase to Mary, save Grandma’s House, get out of the time loop), Wedding Crashers’ goal is more generic. Get the girl. Which I think adequately pulls the film along. But there’s something second rate about it. Like the story’s being pulled by a golf cart instead of a pick-up truck.

Now I’m not saying Wedding Crashers isn’t good. I think there’s a little more going on here than people give it credit for. Arrested development, better known as “man-children unable to grow up syndrome,” is a universal theme that a lot of people are familiar with. I mean, who wants to grow up? Who wants to be responsible? Who wants the fun and excitement and unpredictably of childhood to end? So the fact that these two guys are in conflict with that means we’re exploring them on a deeper level, which again, leads to comedy that resonates more.

I also liked the way the movie handled its dual-protagonists. One of them has a clear goal (get the girl) and the other is stuck along for the ride. And he’s really stuck. The writers put this house out on an island, which was smart, cause that way Vince Vaughn couldn’t go anywhere. This allows them to shit on Vaughn’s character from every possible angle (psycho girlfriend, crazy son, dickhead boyfriend) and that’s where most of the comedy comes from. This is especially important because, let’s face it, the Owen Wilson/Rachel McAdams love story is a little boring.

Still, I’m not sure these writers really understand comedy. Most of the funniest stuff comes from Vaughn and Wilson talking to each other. And as has been well-documented, they wrote a lot of that dialogue themselves. As far as the mechanics of the story go, there were some huge missed opportunities. A lot of great comedy comes from setting up high stakes for your characters and then placing them in a situation where those stakes are in jeopardy. If you throw them into a situation and there are no stakes, no matter how wacky that situation is, it’s not going to generate many laughs. Take the football scene for instance. It’s a cute scene where Wilson is trying to impress Rachel McAdams, but the truth is, there’s nothing really on the line here. None of the plays matter. Who wins doesn’t matter. Contrast that with the volleyball scene in Meet The Parents. Ben Stiller has, up until that point, been desperately trying to prove himself to this family he’s trying to join, and everything he’s done has made them dislike him more. This volleyball game is presented as a last chance opportunity for him to redeem himself, for him to let these guys know he’s good enough for their sister/daughter/niece. That’s why cheap jokes such as him having to wear speedos and him accidentally giving the bride a bloody nose work, because we want so badly for him to make a good impression. All the stuff in Wedding Crashers, including the dinner table scene, are just a collection of gags, of funny jokes (the foul-mouthed grandma, the over-the pants handjob). There was never enough at stake to make the scene really pop.

Another red flag that the writing wasn’t as good here was the villain. I was *just* talking about this the other day in the “What I Learned” section of Happy Gilmore. Shooter McGavin is a character you remember because he’s got more than one dimension. Bradley Cooper’s villain here (the evil boyfriend) has one dimension. The asshole. And that’s why his character is so boring. I didn’t even remember that there was a villain in Wedding Crashers. That’s how little of an impact he left. But this is the writers’ fault. You can’t give us the simplistic “asshole” and expect that to resonate with an audience. It’s boring. You have to add more dimensions.

On the plus side, Crashers uses one of the all-time “always works” story devices and makes it, well, work. Guy falls for girl. Girl has boyfriend. It works EVERY TIME. And the reason it works is this. In any romantic comedy, you have to have someone who wants someone else, in addition to a reason why they can’t have them. If you don’t include the reason why they can’t have them, you don’t have a movie. The problem is, writers try to come up with all these convoluted reasons for why they “can’t have them” (they work at rival companies! Oh no!). But the simplest version of this is also the most convincing, most relatable, and least questioned: They have a boyfriend. Because we’ve all been in that situation before (We’ve liked someone but they were with someone else), we get it. So there’s a natural conflict driving the narrative. It’s not just “will he get her?” We know he can do that. It’s “Will she leave her boyfriend for him?” which is a lot more uncertain.

Another thing Wedding Crashers has going for it is that it has two of the most likable leads you’ll ever see in a comedy. And it’s so funny we’re talking about this since the comedy from yesterday’s review came from the opposite end of the spectrum. But it’s true. Of all the characters we’ve met this week, Owen Wilson and Vince Vaughn are the two we’d most want to spend a weekend with. They’re fun. They’re funny. They’re a little childish, sure, but they’re far from mean-spirited. And that says more than you think it does. Because we talk a lot about how making your characters too likable can backfire on you. If someone’s perfect, how interesting is that? But outside of not being able to grow up, these two are about as “studio-friendly likable” as they come. And we never question it.

My thing with Wedding Crashers is that it’s not a very well-written script. The stakes aren’t high enough. The story emerges clumsily. And most of the comedy is sloppy. But the dialogue and the interaction between the two main characters is enough to make us forget about that *most* of the time. I didn’t hate this movie. I didn’t love it. But I enjoyed it.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: One of the most important rules in screenwriting, and especially comedy, is: “Never include a scene that doesn’t move the story forward.” It’s one of the biggest mistakes amateur writers make. The problem is, there’s a wide-ranging gray area of what it means to “move the story forward.” Well, a great way to see this in practice is to watch the UNRATED versions of comedies. In these cuts, the producers put back in all the scenes they cut out for time. And boy can you tell. The scenes just sit there, bringing the film to a crashing halt, while they dole out some unnecessary joke or advance some pointless subplot. Wedding Crashers (Unrated) has a ton of these scenes, and they make the movie endless. For example, as we’re racing towards the end in that third act and meet Will Ferrell’s character, he talks to Wilson about crashing funerals. In the movie, that’s it. In the unrated version, we actually see them go and crash a funeral. Yeah it’s kind of funny, but it’s not needed.