Genre: Horror/Thriller

Premise: A teen gang in South London defends their block from an alien invasion.

About: Attack The Block has gotten a lot of love recently as it won the audience award at the South By Southwest Film Conference. Writer-Director Joe Cornish is the creator of the iconic “The Adam and Joe Show.” This is his debut feature. Nick Frost stars. Shaun of The Dead and Hot Fuzz

writer-director Edgar Wright executive produced the picture. Here’s a Film School Rejects interview that talks about a lot of the screenwriting aspects of Attack The Block.

Writer: Joe Cornish

Details: 113 pages — 2nd draft – further revisions – April 21, 2009 (This is an early draft of the script. The situations, characters, and plot may change significantly by the time the film is released. This is not a definitive statement about the project, but rather an analysis of this unique draft as it pertains to the craft of screenwriting).

Quick question before I start this review. How come every single successful entertainment person in England is best friends with each other? Can I get someone from England to explain this to me? It’s like everybody not only knows everyone there. But they all spend Christmas together as well.

Anyway……..

I wasn’t surprised when I heard this won the audience award at SXSW because it just sounded DIFFERENT. There aren’t enough ideas that genuinely sound different these days. But this was putting a whole new spin on the “trapped in a room with a monster” sub-genre. The heroes were all wrong (they’re young punks on BMX bikes). The location was all wrong (a block? Not exactly “trapped.”). The construct here had just a unique enough spin to it to set it apart from all its predecessors, yet still feel familiar. And as I’ve said many times before, that’s exactly what you’re aiming for when you come up with your movie premise.

Having said that, I was eager to see how this would read on the page. Although I’ll defend to the day I die that the script has to be good in order for the movie to work, the intensity of the creature feature formula never plays on the page as well as it does on screen. A lot of the fun comes from seeing our characters attacked by monsters, and no matter how perfectly you describe your monster on the page, it’s never going to be the same as seeing it onscreen. That’s usually a good thing though, because that way we can concentrate on what really matters when reading the script: the story and the characters. So I guess the question is…how are the story and the characters in Attack The Block?

It’s South London. A city block. Public housing. Not the kind of place you want to be spending your Saturday evenings. This is where we meet Sam, a mousey pretty girl on her way home from work. But she doesn’t get far before being mugged by a band of teenage hooligans who run the block. Oh yeah, those hooligans would be our heroes in the story, and they’re led by Moses, a selfish heartless bully who’s already looking ahead to the next stage of his life, a life of crime.

Before they can really do anything bad to Sam though, a meteor barrels into a nearby street and out pops a creature that looks like a shaved monkey. So what does our gang do? Why they go over and kill it of course! They then go parading around the block like cavemen, displaying the fruits of their labor to anyone who will listen.

Problem is, more of these meteors start landing, and bigger creatures, creatures that look like sabertooth werewolves emerge, and these alien monsters, for whatever reason, seem dead intent on killing our hooligans, or anything that gets near them.

You may be saying, “So aliens are invading all of London?” Well, not really. Nobody on the news seems to acknowledge these attacks. Nobody texts or e-mails or calls our characters to talk about these attacks. They seem to be centered only around this block for reasons that are anyone’s guess.

Naturally, Sam is forced to team up with the Hooligans in order to survive, and even though these guys mugged her and are assholes and are annoying and are bullies and are the kind of people you’d want to beat the shit out of if you ever got the chance to, they all eventually become friends, running around “the block,” avoiding and killing off these alien werewolves until there are none left.

Ummmm…

Hmmmm…

Truth? This script is…strange. And intense. And messy. And unsure of itself. And strange. Did I mention strange? All these things, I suppose, are normal when writing your first feature script. The difference is, people don’t usually get their first feature script made. So the story has a bizarre manic energy to it that thrives in the script’s best moments, but falters everywhere else. In the end, it was way too redundant for me and I lost interest halfway through.

Yes, it falls victim to the infamous “wash rinse repeat” syndrome. Get into fight with monster, someone from group dies, run from monster to new location, talk a little bit, get into fight with another monster, someone from group dies, run from monster to new location, talk a little bit, wash rinse repeat.

The repetition of this process – which I admit is more necessary in this genre than others – can be offset IF the characters are compelling and have enough going on. But that was my big contention with Attack The Block. I hated the characters. In today’s “What I Learned” section, I include some of Cornish’s thoughts on “likable” heroes, so I won’t get too much into detail here. But let me just say this. I’m okay with making your hero dangerous. I’m okay with your hero not being perfect. In fact, a character should be complicated. But to make your character a complete asshole who bullies and mugs people and has no remorse about it? I mean come on. I’m never going to like that guy.

And I didn’t like any of the characters in this gang. “Punks” is the proper term for them cause they’re just punks, the kind of kids who would humiliate someone on a city corner without a second thought. And these are my heroes? A bunch of assholes? This MIGHT work if a few of our heroes try to change over the course of the story, but at least in this draft (which is admittedly an early one) that isn’t the case. It wasn’t until page 100, actually, that two characters (Sam and Moses) sat down and had a real honest to God conversation about their lives. And it’s quite simple. If I’m not rooting for your characters, I’m not interested in your story.

And that’s why I can’t recommend this. While there may be irony in Attack The Block (the people who usually do the attacking are being attacked) there’s no humanity in Attack The Block. There are no real connections, real feelings, real issues. It’s just people running from monsters or getting shredded by monsters. Sam is an attempt to make some connection with the audience, but she’s dragged along almost reluctantly, as if Cornish knew he needed one decent person on this ride to offset all the cruelty.

Look, I’m sure this plays much better on screen where you’re digging the kills and laughing at the absurdity of it all. And if you’re not as sensitive as I am about how big of dicks all these punks are, you might find yourself laughing at their ongoing commentary of the situation. But in script form, where something more is needed to draw the reader in, it doesn’t offer enough.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Cornish and Wright were asked in the Film School Rejects Article about the daring choice of following antiheroes as our leads. Here’s what they had to say: Cornish: Yeah, I guess that was just because I liked those films. That was very much a John Carpenter-y thing. Specifically Assault on Precinct 13 where the character who’s locked in the prison, he’s a murderer. You don’t know what he’s done. You don’t specifically know what his crime was. Snake Plissken, he’s not a good guy. He’s on death row, isn’t he, or he’s a convict. Vin Diesel in Pitch Black

. I mean, any film about bank robbers, any film about a criminal: Bonnie and Clyde

, Public Enemy with Jimmy Cagney. It’s not a new thing, and I find it very attractive as a writer because it gives you something to write. All characters have to have a problem, otherwise there’s no story. Personally as a moviegoer there seems to be a big thing about making your character sympathetic in the first act at the moment, and people get a bit freaked out if they’re not made sympathetic. But I just wouldn’t have the energy in me to write that story, because it wouldn’t give me anything to write about personally. Maybe it’s because I’m not a good enough writer and I need the bone to chew on kind of thing. — Wright: Yeah, it definitely is a trend where you definitely get notes a lot about people…yeah, there’s definitely a thing within studio films – and independent films – with all films where people financing are just nuts about people being likeable. That tends to where you get a lot of films that are bland because your heroes aren’t allowed to make mistakes anymore. That’s what the whole of your film is about, somebody making amends through a heroic act.

Carson Reaction: All true, but you have to know how to offset the character’s bad traits with good traits so that the audience still roots for them, which I did not feel was the case in Attack The Block.

Edit: Feeling like his best work was not on display here, Stephen has asked if I would post a more recent script of his that he feels more confident in. Since some of you were asking, this is his script that placed Top 100 in the Nicholl. I present to you….Dead Even.

Genre: Thriller (Horror?)

Premise: A recently widowed cop reclaims an old property in a small southern town, only to discover that key figures in the town have been hiding a horrifying secret.

About: Every Friday, I review a script from the readers of the site. If you’re interested in submitting your script for an Amateur Review, send it in PDF form, along with your title, genre, logline, and why I should read your script to Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Keep in mind your script will be posted. Oh, and please, guys, this format only works if you present your criticism in a constructive way. Just be respectful to the writer when giving feedback. Thanks.

Writer: Stephen

Details: 99 pages – 11/15/10 draft

Okay, I admit it. Sometimes (not all the time!) but sometimes, I fall victim to a challenge. If a writer says to me “My script is way better than this,” in reference to some other script I’ve reviewed, there’s a part of me that wants him to prove it. Cause 9 times out of 10, they’re wrong. Their script isn’t better. And Stephen was making some noise last week about how bad the script choices have been for Amateur Friday lately, saying I could easily break that streak if I just read his script. So I decided to take him up on his challenge, and read his screenplay, “The House That Death Built.”

Now afterwards, I was surprised to find a couple of old e-mails from Stephen in my Inbox, and realized that I’d actually already read a script of Stephen’s two years ago – a great comedy premise about a guy who starts dating a girl only to find out she has multiple personalities. But when I read the script, it was a classic case of not exploiting the premise enough. It still needed a lot of work. Well, I’m happy to say, that Stephen’s writing has improved significantly since two years ago, but The House That Death Built still falls a few steps short of the front porch. Let’s find out why.

After opening with a spooky small-town carnival kidnapping, we jump forward eight years into another town where we meet Detective Trajent Future, a New York transplant working in the deep south. Things seem to be going well for Future, who’s happily married with a baby on the way. But unfortunately both his wife and the baby die during a difficult child birth, and just like that Trajent is a widower.

Three months later, Trajent heads off to the tiny town of Malatia, Louisiana to pick up the pieces of his life. Although it’s not clear how he’s affiliated with it, Trajent is reclaiming an old house there, where he plans to get a little R&R before heading back to the city.

Almost immediately, bad things start happening. Trajent can apparently see the past, and inside the house, he keeps seeing flashes of jarred up shrunken heads resting on shelves and lots of young girls being sliced and diced on an operating table. Also, the local sheriff and a few other tough guys send Trajent some not-so-subtle hints to get the hell out of town.

As Trajent begins to dig, he learns that a serial killer who preyed on young female runaways used to live in his house, and use it for many of his sick fantasies. But more importantly, he begins to suspect that key high profile figures in the town are aware of what happened here, and covered it up. But why? Why protect a serial killer? That’s what Trajent’s going to find out.

Okay, first, I want to point out some good things here. This is a great format for a story and almost always works. Guy comes into a small town, starts turning up rocks; the locals get pissed and want him out. Conflict naturally emerges from this situation. The people in the town are protecting their way of life (and possibly something bigger), so the closer our hero gets to uncovering the town’s secrets, the more motivated our locals are to fight back. This story always builds to a perfect climax, as sooner or later it’s either going to be him or them. So from a concept standpoint, “House” is in good standing.

Also, things do HAPPEN. One of Stephen’s complaints last week was that nothing HAPPENED in Vortex. It just kind of trickled along. I wouldn’t call the story developments in “House” anything new, but Stephen *does* keep the story moving. We have a death during childbirth. A move to a new town. Locals give our hero a warning. Hero starts discovering weird shit around his house. One of his only friends in the town dies. He looks into her death. He interviews some of the rich people. There’s a “go go go” mentality here that marches the story along at a pleasant pace.

But here’s the main problem with “House.” It’s sloppy. And I mean real sloppy. Especially the opening act. First we start with this kidnapping of 14 year old Kristy. She’s running through a carnival, trying to escape, then hides in a “white room” which I think is supposed to be some kind of carnival ride. The room begins spinning, and it reads like she’s being pelted with stuffed animals until she dies. I couldn’t believe that we’d have a “death” scene that was so silly, so I assumed I was reading it wrong. But the point is, I couldn’t understand what was happening from the description. And that’s on the writer. The writer has to be clear about the actions that occur on the page.

Next comes our main character’s name: “Trajent Future.” Does that sound like a character in a slow pot-boiling southern thriller? Or does it sound like the protagonist in your next sci-fi flick? It certainly doesn’t sound like the former to me.

Next we have a double time jump. We observe a kidnapping. Cut to 8 years later. Then meet our hero. His wife quickly dies. Then we jump 3 additional months forward. You can do a hard time jump forward once in your opening act, but you don’t want to do it twice (time montages are different). It’s confusing and gives the opening of the script an uncertain sloppy quality.

Then, Trajent arrives in town to reclaim this house, but I’m not sure what this house is. Is this his wife’s old house? Is it his parents’ old house? Or is it his? These are really important questions because it becomes a different story if his parents lived here, or his wife grew up here, or if he has no affiliation with the town whatsoever (although that brings up another question – why would he have property in a town he’s never been to?). I was never entirely clear why Trajent needed to come to this specific town because I didn’t understand his affiliation with this house.

Then, once in the house, Trajent starts having flashes where he can see back to the previous occupant of the house. My question is, how?? Does Trajent have superpowers that we haven’t been told about yet? Or are these flashbacks for the reader’s benefit, meaning Trajent can’t personally see them? This is never explained, leaving us to wonder if this is a supernatural script or not.

Worst of all, the first ten pages are littered with grammar mistakes, spelling mistakes, punctuation mistakes, missed words, and misused words. It’s a cornucopia of sloppy writing. Strangely, once we get past the first 15 pages, a lot of these problems clear up, leaving me to wonder why only the opening of the script was neglected in this manner.

To the script’s credit, the second act *does* get better. Once the procedural stuff starts, we do want to find out these town secrets. We do want to find out who this serial killer is and if he’s still alive. We do want to find out who’s involved in the conspiracy and we do want to see these bad guys go down.

But unfortunately, a lot of damage has already been done. The beginning of the script is so sloppy, and so much of the information given is unclear, that I lost trust in the writer. I didn’t feel like he was giving me his best. And once that happens, once the writer doesn’t have the benefit of the doubt in the reader’s mind, the script is dead. Because every unanswered question or bump in the road is assumed to be a mistake. I mean, how can I trust a writer with complicated plot points when I can’t even trust him to go back and clear up all the punctuation in the first 15 pages?

I do think the second and third acts of “House” were a lot better than what I read in “Three Times A Lady,” the first script of Stephen’s I read. So he’s definitely improving. But this script needed a few more passes.

Script link: The House That Death Built

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Guys, make sure your script is ready for public consumption. Being 65% ready isn’t good enough. Fix the spelling, make sure action descriptions are clear, smooth out the bumps in the road (the double time jump). Part of this is simply giving your script to a friend or an analyst and saying, “Is all of this clear?” But if you jump the gun and throw it out there when it’s only partially ready, it looks bad on you. Cause people are going to assume that this is what you consider “finished” work.

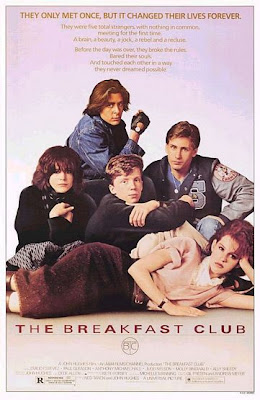

Although I’m a staunch supporter of classic screenplay structure and the core “rules” of screenwriting (three acts, a main character, clear goal, stakes, immediacy), that doesn’t mean I don’t like films that take chances and do things differently. In fact, I love breaking down films that ignore this classic approach (and still manage to be good) just to see how they do it. The other day I stumbled into an impromptu viewing of The Breakfast Club, and I realized, Holy shit, this movie does the exact opposite of some of the things I preach on the site. And yet it’s still awesome. Well, of course after that, I had to start the movie over and figure out why that was. What kind of chances does Breakfast Club take exactly? Well, there’s no protagonist, no single hero to root for. There are no discernable acts in the screenplay. There’s no central goal driving the story. There’s almost a complete lack of plot. There’s lots of talking, very little DOING. Scenes bleed into each other instead of having a clear beginning, middle, and end. It’s messy and uneven and lacks form, and yet despite all of this, it still works. How? That’s what I set out to find out. Here are ten reasons why The Breakfast Club is still amazing despite its structural shortcomings.

CHARACTERS ARE CRYSTAL CLEAR TO US WITHIN MINUTES

Good God is John Huges amazing at setting up characters. He knows exactly what they should be wearing, what they should be doing, and what they should be saying, when we first meet them. But the specific scene I want to highlight here is when the characters sit down in the library for the first time. Yes, John Hughes tells us exactly who our characters are ***by having them sit down***. It starts with Andrew, the wrestler. He can sit anywhere, but where does he sit? Next to the pretty girl. We know what’s on this guy’s mind. Then we have Brian, the nerd. He’s sitting a few tables back when Bender barrels up to him. He threatens a punch and Brian leaps out of his seat, cowering over to the next table. That simple interaction tells us Bender’s the dick who constantly craves attention and Brian’s a big fat wimp. Then Allison sneaks all the way around everybody, emerges at the back table, and immediately buries her head. The weirdo loner. Barely five words have been spoken, and yet we already know who all of these characters are. Brilliant.

FIND AN ANGLE THAT MAKES YOUR SCRIPT A LITTLE DIFFERENT FROM EVERYTHING ELSE

You can’t expect to stand out from the crowd if you’re a follower. You have to do something different with your script. I’m not talking about writing a story that’s never been told before. That’s impossible. Just having your script feel slightly different in some capacity. High school movies through the years have notoriously been chirpy and happy and silly and fun. Breakfast Club, however, goes against the grain and approaches the teen movie from a very dark place. This isn’t done very often, so when it showed up back in 1985, it felt different, new, fresh. What are you doing to make your script feel different and fresh?

CHALLENGE YOURSELF WITH DIALOGUE

There are very few movies as quotable as The Breakfast Club. Part of that is because Hughes was an insanely talented dialogue writer. But I’ve read some of Hughes’ unproduced scripts, and believe it or not, he doesn’t always come up with the goods. That tells me he worked extra hard on Club. One of the keys to coming up with great lines and sharp dialogue is to challenge yourself, to not go with the easy first choice, but to keep digging until you find something original. Your initial idea for a line may be “What an asshole.” But with a little work, you could come up with “That man…is a brownie hound.” Instead of “Nice outfit buddy,” how about exploring 20 more choices until you come up with, “Does Barry Manilow know that you raid his wardrobe?” Dialogue is about challenging yourself. It’s about not taking the easy way out. Clearly, Hughes practiced this philosophy in Club.

CONFLICT

There’s usually an inverse relationship between how simple your story is and how much conflict you need to add. Obviously, you want to pack conflict into all of your screenplays, but if you have a really simple story such as Breakfast Club, the only chance you have of keeping your audience interested is to splurge on the conflict. That’s why we have Bender, whose presence never allows anyone in this movie to be comfortable. That’s why we have Principal Vernon, who hates our high school kids with a passion. It’s why we have the sexual tension (conflict) between Bender and Clair. It’s why we have the alpha male showdown between Bender and Andrew. But probably the biggest element of unresolved conflict in the movie is the need for our five characters to find peace with one another, to “fit in,” if only for a day. The Breakfast Club would’ve been boring as hell if Hughes didn’t know to add layers of conflict.

MYSTERY

If you don’t have any plot in your screenplay, you better have a mystery or two. Here, we’re wondering how each one of these guys ended up here. It’s not a huge thing. We’re not dying to know. But it’s something that’s dangled in front of us and that we’re curious to find the answers to. Of course we can imagine how Bender ended up here. But how did a math dork get here? Why is Little Miss Perfect Claire in detention? Movies are about keeping the mind occupied and holding out a few mysteries for as long as you can is a great way to achieve this.

MEMORABLE MOMENTS

Your script needs memorable moments. How you come up with those moments is never easy, but your script isn’t finished until you have them. The Breakfast Club has several scenes that are impossible to forget. When Bender taunts Vernon until he gives him detention for the rest of his “natural born life.” When Bender reenacts what it’s like at his house every night. When the group is running down the halls together, bonding for the first time. If you want your script to be remembered by a reader, make sure those memorable moments are in there.

DIALOGUE SHOULD HAVE AN ANCHOR

While the dialogue is amazing and off the cuff and original and brilliant in The Breakfast Club, there’s more structure to it than you think. That’s because theme is driving most of what’s being said in the movie. And what is that theme? Differences. Or, more specifically, the struggle for all of us to fit in despite our differences. Discussions range from family lives to sexual adventures (or non-adventures) to high school cliques – nothing they talk about ever strays too far from that thematic core. And I think that’s part of the reason the dialogue is so good, because it has an anchor. Without that anchor, it would’ve been all over the place.

WE WANT RESOLUTION

I’m convinced that the producers of The Real World based their reality show on The Breakfast Club. The reason for this is that in every episode, there are at least two characters with an unresolved issue. By the end of the hour, those characters confront and resolve that issue. This same formula is the engine that drives The Breakfast Club. Ultimately, this is about five people who don’t get along. Our need to see them get along is why we keep watching. That essentially becomes the plot (the “goal” of the film). I always talk about how exploring unresolved issues between characters is a great way to add layers and complexity to your screenplay. Well here, Hughes uses the device to drive the entire plot.

“LOOSE CANNON” CHARACTERS ALWAYS WORK

Loose cannon characters always work. Let me repeat that. Loose Cannon Characters always work. I’m being a little facetious because I’m sure you can point to a few examples where they haven’t worked, but in most movies, the liberties that a loose cannon character affords you (the ability to say things and do things other characters wouldn’t be able to say or do), usually results in a lot of amusing situations. Bender is a perfect example of how a single loose cannon character can elevate a movie to a whole new level.

WHEN YOU DON’T HAVE HARD STRUCTURE, USE SOFT STRUCTURE

Couple final things here. While we don’t have a ticking time bomb in The Breakfast Club, we do have a ticking clock. Our characters are in this location until the end of the day. It may not seem like much –nothing blows up if our characters don’t save the day – but you comfort an audience when they know the schedule of your story, as silly as that sounds. Also, while we don’t have any really strong character goals (find Doug!), each of our characters does have a “soft” goal. They must write an essay by the end of the day describing who they think they are (not surprisingly, the essay stays close to our theme!). In both cases, Hughes added soft structural components to help keep the screenplay on track.

So, as you can see, structure can be found in the most structure-less of places. A soft ticking clock, subtle character goals, unresolved relationships, and a dominant theme all help hold The Breakfast Club together. But I admit, this one was kind of easy. Maybe next week I’ll challenge myself with something a little more complicated. Any suggestions on a structure-less screenplay to break down?

Genre: Comedy

Premise: An uptight secret service agent is assigned to the worst former president in U.S. history, who becomes the target of an assassination attempt.

About: Spec script El Presidente was picked up by Warner Brothers late last year, but I could’ve sworn this script was kicking around a couple of years ago with Tom Cruise and Jack Nicholson attached. Is that me imagining things or was that another project altogether? The writer, Dan Goor, has been working as a TV writer for over a decade, writing for Conan O’Brien and Jon Stewart, as well as NBC’s Parks and Recreation. This is his first script sale.

Writer: Daniel J. Goor

Details: 120 pages (This is an early draft of the script. The situations, characters, and plot may change significantly by the time the film is released. This is not a definitive statement about the project, but rather an analysis of this unique draft as it pertains to the craft of screenwriting).

Agent Coleman is the kind of guy who tries to beat his best time jogging every morning. He’s the kind of guy who eats steamed broccoli for breakfast. Agent Coleman is the most uptight by-the-books secret service agent you will ever meet. And that’s saying something. Since all those guys are more anal than a night at Charlie Sheen’s house (ooooh, I just had to go there, didn’t I).

40-something Blake Fisher is the opposite of Coleman. He’s a loser. An idiot. A child. Careless. Selfish. Undisciplined. Narcissistic. Oh, and he also used to be president of the United States. Not by the people’s vote though. No, Fisher lucked out when the real president suffered a chest-grabber during office. So Fisher took over. And proceeded to fuck up everything. At the heart of the criticism was that Fisher cared more about the celebrity of being president than the actual job of being president. His sexual endeavors alone made Charlie Sheen look like David Archeletta (please nobody get that reference). Afterwards he was immortalized by the definitive best selling biography, “Worst Ever.”

Anyway, Coleman has done his two years of security detail with Fisher post-presidency and now he wants a shot at the big time – the thing that every security agent dreams of – to protect an acting president. Although he’s a front-runner for the job, Coleman is shocked when he’s rejected for the position, and to add insult to injury, is told he’ll be guarding Fisher for another two years!!! The nightmare continues. And the reason it’s a nightmare is because nobody gives a shit about Blake Fisher. Nothing bad is ever going to happen to him, making Coleman’s job a joke.

Concurrently during all this, we keep cutting to newscasts telling us about “Armorcorp,” a new privatized army system that comes into your country for a fee and cleans up your mess. Armorcorp’s first job – The Congo – is going so well, that Congress is ready to pass a bill at the end of the week which will give their business the kind of autonomous power only individual countries receive. Hmmm, why do I get the feeling these Armorcorp people aren’t looking out for the world’s best interest.

Back in the U.S., Coleman becomes so frustrated with his situation that he slacks off for the first time in his career. And wouldn’t you know it, it’s during that very second that a group of men kidnap Fisher. Colemam, however, is able to catch up to and get Fisher back from these men, men, he’s shocked to find out, who work for his very own government. Wait a minute, why would his own government want to kidnap and kill a stupid ex-president that nobody cares about? And if they have no problems killing Fisher, who’s to say they’d have any problems killing him?

Uh-oh, This is not looking good. And it’s just a guess, but why do I feel like Armorcorp has something to do with this (maybe because I decided to include a paragraph about them?)? Will Coleman figure this all out in time to save himself and, more importantly, the man he’s assigned to protect?

The first thing I want to point out about El Presidente is the character introductions. When you’re writing a high concept comedy, you want the reader to know who your characters are right away.

Here. We meet our lead character, Coleman, jogging faster than everyone else on the path, running up 42 flights of stairs to his hotel room, ordering a very specific meal from room service (6 eggs, steamed broccoli, etc.), pulling out a portable blender so he can mix his omelet just the way he wants it. Next, we meet Fisher, who’s passed out amongst a sea of bras with a naked women stumbling around.

After each of these introductory scenes, we not only know exactly who these characters are, but we know exactly what their flaws are. Coleman is too uptight. Fisher is self-destructive.

Now hitting these moments too hard in other genres, like drama or horror, doesn’t work. The tone of those types of movies require you to be more subtle with your introductions. But in comedies, where you’re allowed to be on-the-nose and obvious if it’s servicing a laugh, you can use those opening scenes to tell us exactly who your character is. How do we meet Jim Carrey in Liar Liar? He’s lying to a judge trying to win a case at the expense of his dignity. We know exactly who that character is before we’ve hit the third minute of the film.

As for the rest of El Presidente, I think it’s still being worked out. Like a lot of comedies, they’re trying to find those gold “laugh out loud” set pieces with varying degrees of success. While there was nothing side-splittingly funny in El Presidente, there were a lot of amusing scenes, including a car chase in a Prius and an impromptu baseball stadium “Ex-President throws out the First Pitch” scene to escape the bad guys (where they run onto the field in the third inning – not exactly the moment you’re supposed to throw out the first pitch).

But a lot of the stuff felt like we’d seen it before. When I heard about this movie, I actually thought it was going to be set in the Congo, and I liked that. Not only did it sound like it had a ton of potential for comedy but as far as the “buddies-on-the-run” comedy genre, I don’t think anything like that has ever been done before.

Another reality that’s hitting me with comedies these days is that the plot just doesn’t matter enough to people anymore. The plot in El Presidente seems incidental, like its off on its own island (literally I guess). And while a part of me understands that on a primal level, the comedy should always take precedence over the plot in a comedy, it’s my belief that a well-crafted plot provides you with more opportunities for comedy than a non-existent or super-thin plot. If you look at a movie like “The Other Guys,” for example, the plot was so nonsensical and stupid, that the back half of the movie ran out of laughs. And I think that’s directly related to the plot petering out. It isn’t there to push any important scenes (with real stakes) on the characters, leaving the actors out there to fend for themselves. I mean seriously, what the hell was that 15 minute scene near the end where they kept walking back and forth between the house and the street pretending to be a grandma?

Anyway, it sounds like I’m dogging El Presidente but I actually think it’s better than most comedy specs I read. It has a very Midnight Run (speaking of a comedy with a solid plot) feel to it that, if honed in subsequent drafts, could really shine. I sure would’ve liked to see this set in the Congo though, where it would’ve given us something fresh. But hey, it’s still worth the read.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: When doing an “on the road” comedy (or really any comedy where your characters are bouncing around from location to location ), you owe to yourself to look at every possible location for that story. A road trip in the deep south will be different from a road trip in the Midwest will be different from a road trip in India. Obviously, you want to choose a location that best fits the story you’re trying to tell, but just remember that the more unique the location is, the more opportunities you’ll have to give the audience something they’ve never seen before. I remember the writers of Due Date being interviewed about the writing process of that script. And they talked about how frustrating it was to try and come up with a fresh angle for all their road trip scenes as it had all been done before. I think a lot of the reason for that is they put their characters in too familiar of an environment. There’s only so much you can do on a road that thousands of road-trip films have traveled before.

Genre: Action-Adventure

Premise: Indiana Jones goes in search of the famed “The Lost City Of The Gods,” which is supposed to hold inside it all the knowledge in the universe.

About: Before Spielberg’s go-to writer David Koepp wrote Crystal Skull, super screenwriter Frank Darabont worked on a draft of the script. Darabont, like many who took on this role (I think 7-8 writers in total worked on the project) expressed dissatisfaction with how unfocused Spielberg and Lucas were, and the impossibility of satisfying both. Word on the street is, Spielberg backed Darabont’s draft, but Lucas didn’t like it.

Writer: Frank Darabont

Details: 140 pages – 11/4/03 (This is an early draft of the script. The situations, characters, and plot may change significantly by the time the film is released. This is not a definitive statement about the project, but rather an analysis of this unique draft as it pertains to the craft of screenwriting).

It’s baaaaaaaaack. Yay! More Indiana Jones debate! You guys wanted me to review Frank Darabont’s Indy 4 draft so here it is. The plan here is to do the usual break down and analysis. But let’s be honest. The reason to review this script is to figure out which is better, City of Gods or Crystal Skull. Did our crime-fighting beard-donning duo drop the ball by spending another four years to come up with Crystal Skull when they had a great script right under their noses? Or was Darabont’s Indy interpretation as off-target as Lucas insisted?

What’s lost in all of this is an old interview M. Night gave at the peak of his powers, when he was recruited to write a draft of Indy 4. He said that Spielberg and Lucas had all these story elements they absolutely had to have in the script, and M. Night simply couldn’t work that way. In fact, the deciding factor may have been Darabont, who said to Night that the writing of the script was basically a “wasted year of my life.” Ouch. The irony, of course, is that Night would give up his youngest child to get an Indy writing assignment from Lucas and Spielberg these days. But I digress.

Hey, what do you know, Gods starts out with cars racing in the desert. Kind of like Crystal Skull. And just like Skull, none of our main characters are in those cars. Why would they be? That would be exciting. Instead, we have Indy hanging out at desert non-spot “The Atomic Café,” pawning off pottery barn level relics to his good friend Yuri, a jovial Russian who for some reason finds value in this garbage.

Someone pointed out in the Skull comments that the opening of Gods sucked because Indy was introduced in a café doing nothing. I agree that introducing Indiana Jones in any sort of passive or reactive manner is a risky proposition. But at least here there’s a character motivation for it. Indy is retired. He’s too old to go swashbuckling for ancient treasures anymore. I liked that. It made sense in the context of where Indy was in his life. However, like most elements that hold promise in Gods, it’s forgotten soonafter, and never heard from again.

In a bafflingly clumsy segue, we cut to a few hours later where Indy is hanging out in the desert eating lunch and he spots a few military men right there in the open, lining their cars with artificial “American” insignias. And at the helm of this tomfoolery? Yuri!

Indiana decides to follow them, taking them (and him) into that AREA 51 warehouse that Skull starts with. Personally, I thought this was a better choice to open the film, since Indy DECIDES to go on this adventure instead of being roped into it. He *wants* go after Yuri, making him, and the whole warehouse sequence, more active.

We then, of course, get the whole atomic bomb sequence because Spielberg just had to have it in there. And afterwards, just like Skulls, Indy gets fired from his job. This is followed by a rather clumsy “Indy gets drunk in a museum scene,” which at first I hated, but then when I remembered he was basically responsible for getting half these relics on display, there was a poignant sadness to it that ALMOST worked.

After a fight to the death with the evil “Thin Man,” Indy gets a key to a locker at Grand Central station where he finds the Crystal Skull (yay! The Crystal Skull lives!), and is immediately mistaken for someone else who gives him a ticket to Peru to meet his “contact.” (uck. My guess is that Lucas is responsible for this choice, as he used the same painful plot device in Attack Of The Clones, when Obi-Wan was conveniently mistaken for an evil jedi at the Clone Farm).

Off we go to Peru and who’s Indy’s contact? Why Marion of course! Finally, around page 50, the plot to City Of Gods is revealed. They must find the Lost City Of The Gods, where this skull will reveal an unknown power. So Indy and Marion buddy up with an expedition team (no Mutt), head into the jungle, and try to find the mythical lost city, while two groups of baddies (I think it’s two – it’s not entirely clear) are hot on their tail.

So, let’s get to it, shall we? Which script for Indy was better? Gods or Crystal Skull? If my life was on the line and I had to choose one, I’d probably choose this one. But it wouldn’t be easy. Here’s the thing. City of Gods was more focused. Things made more sense. Once we actually get to our story (Find the Lost City Of The Gods), we actually know what’s going on. Whereas in Crystal Skull, I was constantly confused about where we were going and why we were going there.

However, Crystal Skull was just more…fun. I mean it’s hard for me to say that since that script is so damn all over the place, but the three-way dynamic between Indy, Marion, and Mutt, believe it or not, is more fun than any of the character dynamics in City Of Gods. And that’s surprising because Darabont actually comes up with a way more interesting dynamic than adding Mutt to the fold.

Here, Marion has a husband, Baron Peter Belasko, a wealthy archeologist who’s in it more for the fame than the hunt, and who has numerous best-selling books about archeology. In other words, a big fat fake. Really, the PERFECT foil for Indiana Jones, made even more perfect by the fact that he’s married to the woman Indy still loves. I mean, this was just ripe for comedic conflict-packed banter. And yet…it’s barely explored. Maybe it’s because Belasko comes into the story so late but he just never becomes a big enough character to care about (we never truly believe they’re married even). This leaves Indy and Marion treading the same dialogue waters they’ve always tread, giving their relationship a “been there done that” feel.

City of Gods also suffers from a lack of interesting bad guys. Some of you pointed out how Russian Pyschic Chick from Crystal Skull sucked as a villain because she wasn’t the least bit threatening. She never killed anyone. Never did anything that bad. In retrospect, I agree. If we’re not afraid of your villain, we’re not afraid of what happens to our heroes if they get caught. Here, we have the jovial Yuri, who I’m about as afraid of as a tickle me Elmo doll, and some local guy who’s so forgettable I don’t even remember why he was chasing Indy in the first place. So the lame villain streak continues.

The thing is, the scariest character in both movies, a tall pale Harry Potter-like villain named The Thin Man, is killed off before we even start our adventure. I mean of the 260 pages (in both scripts) of searching for ANY memorable villain, they actually had one and they killed him off BEFORE the plot started!!

There is one aspect I really liked about Gods, and that’s an ambitious and well-crafted airplane chase sequence. It was the only scene in both Gods and Crystal Skull that brought something new to the Indiana Jones franchise, and yet felt like it was steeped in what made the original movie so fun. You have our characters walking along the wings of bi-planes, moving from one plane to the other, all while fighting off baddies. It was quite clever, and my favorite part of the script.

As for the silly stuff, there’s no vine-swinging in Gods. Oxley is WAAAAAAAAAAAAY less annoying in this one (although he is kept in a cage like an animal, lol). A giant snake eats Indy in this one (The power of the Lost City has affected the growth of animals in the area so all the animals are bigger – I seriously doubt Darabont had anything to do with this idea). And there’s still a spaceship in the end.

But what’s different is the entire final act has way more purpose in Gods. You actually feel like their exploration of the city is structured. That there’s a point and plan when they go inside (return the skull, which will result in the City showing them all the knowledge in the universe). In Crystal Skull, I had no idea why we were in that cave at any point.

All this brings about a question I can’t help but ask. There’s a lot of people on this board who would die for the opportunity to write an Indy film. So let me ask you, if you were to write Indiana Jones 5, what would your plot be? Let’s see if you can outdo Lucas and Spielberg at their own creation.

Script link: This script is out there in several places via a google search.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: We all get attached to scenes/characters/and moments in our screenplays. But over time, screenplays change. They take on a new direction, and many of the elements in that original version you conceived no longer apply. If you try and hold onto those elements (even your favorite ones), they may prevent your story from reaching its potential. It’s clear that Spielberg and Lucas had a list of “must-haves” they included with every Indiana Jones 4 writing assignment, and that those elements weren’t working. I mean, if you give your script to 7-8 of the best screenwriters in the business and all the scripts come back sucking, chances are, it’s not their fault. I find that, sometimes, getting rid of that scene you love so much from the original draft can open the door to a million new story possibilities. In other words, don’t be afraid to get rid of something you love if it means improving the overall script.