Genre: Sci-Fi/Comedy

Premise: Every man in the world is dead except for a young slacker and his pet monkey, leaving a world entirely populated by females.

About: Brian K. Vaughan is a comic book writer, a TV writer (Lost), and has sold a few spec screenplays. This is an adaptation of Vaughan’s own comic book, Y The Last Man

, which he sold a few years back.

Writer: Brian K. Vaughan (Based on the series from Vertigo Comics Created by Brian K. Vaughan & Pia Guerra)

Details: Draft 1.2 (This is an early draft of the script. The situations, characters, and plot may change significantly by the time the film is released. This is not a definitive statement about the project, but rather an analysis of this unique draft as it pertains to the craft of screenwriting).

There are few screenwriters out there who have as much geek cred as Brian K. Vaughan. You say his name and geeks everywhere smile unintentionally, their cheeks turning red the way a 13 year old girl reacts when the school stud says hi to her in the hallway. I, however, am still undecided on Vaughan. I loved the majority of Roundtable, his Ghostbusters-like spec sale from a few years back about modern day knights trying to save the world. But The Vault left me colder. I liked it enough to recommend it, but parts of it were just so weird and out there. The guy’s imagination is so deep it gives George Lucas pause, and at times that gets him into trouble. But I knew this one was supposed to be good. Plenty of people have recommended it to me before, so I was more than happy to finally read it. Indeed, it starts out with a great question: What if you really were the last man on earth?

Y The Last Man starts the way a spec script should: with something happening. And boy is something happening. Moms are driving their dying husbands and sons to the hospital. Businessmen are keeling over mid-stride. 747s are crashing into the middle of cities. It appears we’re smack dab in the middle of the Apocalypse. Well, sort of anyway. We realize quickly that this apocalyptic event is selective, only killing off the men in the world, sparing the ladies and girls completely. Within 5 hours, every damn living creature with a y chromosome is a burnt pop tart, el officio deadondo.

Or wait, not EVERY living man. It appears that eternal slacker Yorick Brown and his pet monkey, Ampersand, have somehow survived this ordeal. We’re not sure how yet but a guess is that the monkey has something to do with it. So Yorick throws on a gas mask to disguise himself, and heads to his mom’s place, where he hopes she’ll know what to do. Shock City then when his mom betrays him and calls the CIA!

Yorick grabs the monkey, jumps out the back window (don’t you love how awesome back windows are in movies?) and sprints for his life. A test subject for the remainder of his existence does not sound like fun. The last Yorick heard, his girlfriend, Beth, touched down in Los Angeles, and the poor romantic sap feels like if he can just make it to her, everything will be okay. Too bad finding your girlfriend in an apocalyptic wasteland isn’t as easy as jumping out the back window.

Unfortunately, Colonel Alter Tse-Elon, a female soldier in the Israeli defense force, hears about Yorick and makes it her mission to find him. She believes (I think – I wasn’t clear) that if Yorick is found alive that the earth could be repopulated with men, the root of all war, and that once again Israel would be subject to attack. Finding and killing off Yorick would essentially ensure world peace.

And you know what? She’s not the only one who wants to take Yorick down. A huge female biker gang that may or may not be hardcore feminazi lesbians, discover the presence of Yorick and want to pave his way down the Highway to Hell as well. Ugh, not good.

Luckily Yorick runs into Agent 355, a smoking hot secret agent for…some really secret agency, who decides to help him get to Los Angeles. She’s really the only thing that stands between him and capture, as she fights off the biker chicks and Israeli army at every turn, all the while trying to convince Yorick to offer himself to science so they can repopulate the world with men. Will this happen? Will the world’s biggest slacker be able to save mankind? We’ll have to see.

Y The Last Man is as crazy as it sounds. And that’s both its biggest strength and its biggest weakness. What I like about Vaughan is that he gives you what every reader asks for. Surprise. Show me something different. And when Vaughan writes, indeed, you’re never quite sure what’ll happen on the next page. But it’s a double-edged sword, since what you get isn’t always satisfying, and occasionally is so broad that even the developers of those weird Japanese video games step back and say, “Whoa dude, not bi-winning, too far.” A lesbian biker gang? The Isralei army? A pet monkey? It’s not as out there as The Vault, but you definitely need to be up for the absurd when reading one of Vaughn’s scripts.

On the technical side, I wished Vaughan had explored his premise a little more. What if there really were no men left in the world? There’s a great little scene early on where this super-hot chick pulls up in a garbage truck (which she can barely drive), clumsily screwing up her job at every turn, and we’re going, “What the hell is this girl doing driving a garbage truck?” And she explains how she used to be a model, but when all the men disappeared, there was no use for models anymore, forcing her to take the lowliest of lowly jobs. True it was a gimmicky scene that had nothing to do with the plot but I loved that it was actually exploring the premise in a clever way. And I wanted to see more of that. There’s a little of it (the energy sector was dominated by men so there’s basically no electricity anymore) but I was hoping for more.

Structurally, the script has some good and bad things about it. You have a main character with a clear goal (“Get to Beth”) and plenty of urgency behind the goal, since Yorick is constantly being chased. Remember, if you don’t have a ticking time bomb in your script, a great supplement is to create a chase scenario. If someone’s always on your hero’s heels, it creates the illusion of a ticking time bomb. And whenever you have a road trip scenario, you probably want someone chasing your characters anyway, as it gives the story an added edge.

On the stakes front, I’m not sure the script achieves its goal. While Yorick IS the last man on earth, and therefore the last chance to save mankind, that’s not what his mission is about. His mission is to get to his girlfriend. It’s not like Will Smith in I Am Legend, where his goal was to come up with a cure to save makind, truly high stakes. Yorick is trying to get to Beth, which doesn’t really do anything but…get him to Beth. If you look at a movie like The Day After Tomorrow

, where a father is trying to find his son, him finding his son actually means something, since he (as well as everyone) is in danger. Beth’s not in danger. And on top of that, when we last saw these two together, she didn’t even like Yorick, so the stakes driving the story are a little soft.

The biggest misstep, however, was one I noticed only because I’d watched Raiders recently. Every third or fourth scene In Y The Last Man is Yorick and Agent 355 in a safe setting (on a train, on the side of the road) talking. These scenes are weak because the story isn’t being pushed forward in any noticeable way. Instead, the characters are talking about their pasts or discussing the effects of the plague. They’re not TERRIBLE scenes because Vaughan is good with dialogue (i.e. “You know what the strongest muscle in the human body is?” “The heart?” “No, it’s not the heart, you sappy fuck. It’s your jaw muscle. Even a scrawny dude like me has five hundred pounds of bite strength.” “Great, that’ll come in handy when you’re fighting food.”) but there’s no outside force or conflict or subtext going on during them. It’s just two people talking.

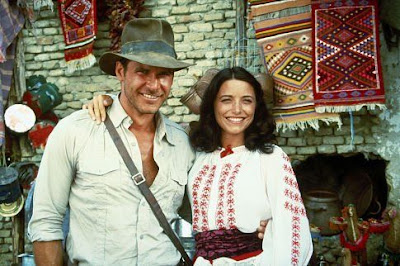

Compare that with the “dialogue” scenes between Indiana and Marion in Raiders. When he first finds Marion, he has to convince this woman whose life he ruined to help him. Or later on when they’re talking in Cairo, the baddies are moving into place to attack them. Or when she’s dressing Indy’s wounds, probably one of the truest “straight dialogue” scenes in the movie, even there the sexual chemistry that’s been building through them the entire movie is about to burst. In other words, there’s ALWAYS SOMETHING GOING ON in those scenes, whereas here in Y The Last Man, it just feels like two people talking. This is more a testament to how good Raiders is than any defining statement about Y The Last Man, but it is a reminder to add layers to your dialogue scenes.

In my opinion, Y The Last Man is too broad, too loose with the reigns, but there’s no denying that Vaughan always keeps you guessing and has some of the more unique characters you’ll find in a script. You want to talk about a unique voice, a voice that separates a writer from everybody else out there, go ahead and read one of Vaughan’s scripts. And for that reason alone, I think Y The Last Man should be read.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: I’m surprised I’m bringing this up with a Brian K. Vaughan script, since I just championed his originality, but this is proof that even the top writers fall into the same traps as the rest of us. No less than six days ago – SIX DAYS AGO! – I read an apocalypse script where in the opening scene, a jumbo jet crashes into the city. What happens in the opening scene of Y The Last Man? A jumbo jet crashes into the city. This is proof that ALL WRITERS THINK ALIKE. We think apocalypse and we imagine a plane diving into the middle of New York. It’ll be epic! But did we ever stop to consider that everyone else who’s writing an apocalypse script would think of the same thing? For that reason, always keep your competition in mind. Ask yourself if another writer would write the same thing. And if they would, write something else. Maybe an oil tanker with no one at the helm plows into the port instead. I don’t know. But keep in mind that that cool original scene you just wrote? A reader may have just read it last week. Which means you’re playing the role of second fiddle.

When Roger came to me wanting to review Stoker, the Wentworth Miller screenplay, I said, “As long as there are plenty of Prison Break jokes.” But I don’t think Roger’s ever actually seen Prison Break, which leaves the joking to me. Did anyone here watch that show? It was called Prison Break yet they broke out of the prison after the first season. Isn’t the show over? I’ve never seen a show/plot strain so hard to keep its characters together. They eventually ended up in Mexico in another prison, but get this, the prison was so relaxed that the characters were actually allowed to roam the basement area unattended. So the first prison was the most secure prison in the world and they broke out of that. Now they were having trouble breaking out of a prison where they could hang out in the basement for days at a time without anyone knowing or caring? I kept watching out of sympathy for the writers, who were tasked with making this whole thing conceivable. Eventually someone realized, “What are we doing?? None of this makes a lick of sense,” and they put the poor show down. But Prison Break will be immortalized for its ability to continue on longer than any dead show in history. And people thought Lost had filler. Anyway, I have great news. I’m reviewing an awesome comedy later in the week. It sold earlier in the year so if anyone wants to guess what it is, please do so in the comments. I’m also reviewing a haunted script. Unfortunately the only thing scary about it is the comedy. Should be a groovy week. Now here’s Roger with his review of Stoker.

Genre: Drama, Mystery, Thriller

Premise: When India Stoker’s father dies, a mysterious man arrives and claims that he’s her long lost Uncle Charlie. As he integrates himself into the wealthy family, the eccentric teen is torn between trusting a man who may be an imposter and discovering her true nature.

About: Ted Foulke is the pseudonym of Prison Break star, Wentworth Miller. Carey Mulligan and Jodie Foster are attached to the project under Ridley Scott’s Scott Free production banner. Miller has actually written two scripts (the prequel script is called “Uncle Charlie”) about the unusual Stoker family and is presumably going to play the role of Uncle Charlie in both.

Writer: Ted Foulke

I was sucked into this script without knowing it was written by “Prison Break” star, Wentworth Miller. What caught my attention was the Edward Gorey-esque illustration of a girl on the cover, and I opened it and was enamored by the writing (the description and destruction of a spider as said girl plays a piano) within the first three pages. Intrigued, I paused to look up information on the script, and quickly discovered that the screenwriter, Ted Foulke, is the non-de-plume of the actor who played Sunnydale swim team member turned Lovecraftian fish monster on season two of the Buffy: The Vampire Slayer.

Genre: Comedy

Premise: Three men on the verge of middle age celebrate a bachelor party at Glastonbury, a notorious mythic music festival in the UK.

About: (Correction – Although Sean does have credits, he does not have representation). — If you are a repped or unrepped writer, feel free to submit your script for Amateur/Repped Friday by sending it (in PDF form) to Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Please include your title, genre, logline, and why I should read your script. Also keep in mind that your script will be posted.

Writer: Sean Vaardal

Details: 103 pages – Feb. 14, 2011 draft

Lots of people have asked me to write an article on what makes a great query letter. That article has been written somewhere in the neighborhood of 713,000 times already, so I’m not going to rehash it here on Scriptshadow. But I will broach the subject because Sean’s query to me is the reason I picked him for today’s review. Before I get to Sean, let me address a few general thoughts.

Guys, I love you. And you send me some really passionate stories about how difficult it is out there and how hard it is to get your work noticed. However…I can’t pick your script when every tenth word in your query letter is misspelled. i can’t pick ur script if u don’t capitalize or punctuate correctly or if you write 2 me in text speak. I can’t pick your script if you ramble on incoherently about your concept or your aspirations. If you ramble on in a 500 word query letter, I can only imagine how unfocused your screenplay is going to be.

You need to approach your query letter with the same level of professionalism you’d imagine Ernest Hemingway would have done it. That’s not to say you should be buttoned up and humorless. But be focused, devoid of mistakes, and get to the point quickly. I thought Sean’s query was pretty much perfect, so I decided to include it here. Here’s what he wrote…

Dear Carson,

I am a scriptwriter with credits on two award-winning British comedy shows Smack The Pony and Monkey Dust.

I would like to send you my new feature-length script, a comedy called Glastonburied.

I got the idea after an article in The Economist, which said 43 is the age at which you are apparently no longer young. According to this, I have only 6 months left before I am ‘officially’ old. But what I want to know is: How do you stop being young, and are you supposed to? And if so, when does the wisdom start kicking in?

I thought this ‘tipping point’ idea was a good way of analysing three, 40-something friends over a weekend at the Glastonbury music festival. A place where people go to lose themselves or find themselves. A place where all your dreams can come true, a place of myths and legends, bands and chaos, where you might enter an innocent but leave with a rare, new kind of knowledge.

Glastonburied is like The Breakfast Club for adults. It combines male identity themes reminiscent in Sideways, with the added mayhem of Withnail & I.

Go on Carson, you old mucker, make it your Amateur Friday pick of the month.

Cheers,

Sean

Now I don’t know what a “mucker” is, and I’m not going to speak for every agent, manager, and producer out there, but I’ll tell you why this worked for me. First, he exhibits a clear grasp of the English language, which indicates to me that at the very least, his writing will be easy to read. Next, he uses a well-known trick to pitch his idea – relating his screenplay to his own life. If I believe that there are some personal issues you’re exploring in your script, I know I’m reading something meaningful to the writer, which almost always ends up in a better screenplay. Sean also gives me a couple of movie references so I know what to expect, and ends with a pleasant-humored challenge, encouraging me to give his script a shot.

Now, of course, this query got me to read the screenplay. But that doesn’t mean I’m going to like it. Did I like Glastonburied? Read on to find out.

Gary Newman is a piano bar singer just north of 40 who’s beginning to have panic attacks during his performances. It seems as if Gary’s directionless life has finally caught up with him, a life that was once quite promising . You see, back in 2003, Gary won one of those “Idol” shows in Britain, and was for a brief time on top of the world. Clearly, that top has bottomed out.

Adding salt to the wound, Gary’s fiance just called off their wedding. The reason being simply… he’s a shell of his former self. It would’ve been nice, of course, if she would’ve told him this BEFORE Gary’s two best friends showed up for his weekend bachelor party. And because Gary doesn’t want to deal with the consequences of telling them what happened, he decides to keep the break-up a secret.

The friends in question are Jeff, a once moderately successful actor, not unlike Thomas Hayden Church in Sideways, and Keith, a rich family man desperately clinging to his youth. The three of them head off to Glastonbury, a famous/infamous music festival where people go to lose themselves, in search of one last wild time together before Gary gets married (or not).

Naturally, once they get to the festival, all hell breaks loose. A urinating witch immediately puts a spell on them, they befriend a couple of hot young ladies who may be Nazi sympathizers, they meet and participate in some local cult rituals, and of course do a lot of drugs. The characters in Glastonburied do a LOT of drugs. In the end, Gary must decide whether to embrace the next stage of his life or stay trapped in his middling existence forever.

Alright so, first off, let me just say, Sean, I’m on your side. I liked the presentation. I liked the pitch. But since it does nobody any good if I sugar coat my reaction, I’m going to hold Glastonburied to the same high standards I hold million dollar sales. I think this script needs a considerable amount of work. And it starts with the main character. I have a tough time accepting lead characters as celebrities or former celebrities in a character piece, because there’s nothing relateable to an audience about someone who’s a current or former celebrity. Think about it. How many people have won an American Idol like competition in their life? 200? 250? So that’s 250 people who know exactly what your main character feels like. There are obviously exceptions and there was a connection between the character’s past (he’s a musician) and the current situation (he’s at a music festival), but here’s the specific reason why it didn’t work for me: It was false advertising. In the query letter, it was implied I would read a personal everyman journey. That’s the whole reason I wanted to read it! Because it was tackling a normal everyday guy’s collision with that most relate-able of relate-able situations: getting older. So when the main character was given this totally specific celebrity past, every drop of realism, every ounce of that “everyman” I was hoping for, instantly vaporized.

I was also bummed about the way the story was set up. What hooked me in the query was the bit about a guy learning he had six months before officially becoming “old,” and therefore wanting to do something exciting with his last bit of “youth.” But in the script, this line (about becoming 43) is buried deep within the second act, long after it’s lost its significance. That line was the perfect inciting incident for the movie and the fact that it has nothing to do with why he and his friends go to Glastonbury was a bummer.

The structure here needs work as well. Glastonburied is missing three very important story elements: A character goal, stakes, and urgency. Gary isn’t trying to obtain any goal in the script other than a vague sense of holding onto his youth. And since he’s not trying to obtain any goal, there are no stakes to his journey. You can’t gain or lose anything if you’re not going after anything in the first place. And of course, since there’s no goal or stakes, there’s no urgency. You can’t be in a hurry to achieve anything if there’s nothing you’re trying to achieve.

This leaves the plot in the same hole so many other struggling comedies find themselves in: it’s essentially a loosely connected series of comedic situations. This is great if you’re directing a Saturday Night Live episode, but not if you’re constructing a story where all the pieces are supposed to fit together.

Let’s go back to Hangover to see how this is executed. Notice how CLEAR these three elements are.

Goal: Find Doug.

Stakes: If they don’t find him, he doesn’t get married.

Urgency: They have two days before the wedding.

I’m not saying to copy this exact structure by any means, but these elements need to be in place for a comedy such as this to work. You also need to be aware of when specific story choices eliminate these opportunities. For example, Gary’s wife breaking up with him before the bachelor party was an interesting choice, but in making that choice, the ticking time bomb (urgency) was eliminated. There’s no need to get to the wedding if the wedding doesn’t exist.

I think a lot of my reaction goes back to the fact that I felt misled from the query. If this was going to be a goofy romp with lots of drugs and pissing witches and strange cults and that sort of thing, that’s fine. That type of comedy can work. But if I’m going in believing this is another Sideways or Breakfast Club

, I’m going to be sorely disappointed. That’s a big lesson I learned here. Don’t falsely sell your script in your query. Make sure it’s representative of what you’ve pitched. But hey, maybe I’m being way too hard on Sean here, and since you guys will be going in with a better understanding of what the script’s about, you very well might love it. A comedy set at one of these crazy ass music festivals is a good idea. Download it yourself and leave your thoughts in the comments section.

Script link: Glastonburied

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Whatever genre you’re writing, make sure the tone of your query reflects that genre. So if it’s a comedy, throw a joke in the e-mail to prove that you’re funny. If it’s a dark drama, keep the query more professional and straight-forward. Whatever the case, please, before you send your query to anyone, give it to your parents or the most anal punctuation/spelling Nazi you know and ask them to weed out all of the mistakes. It’s hard to catch the eye of someone in this industry. They’re all so busy. So bring your best game to that query.

A couple of weeks back I posted my “10 Great Things About Die Hard” article and you guys responded. To quote Sally Fields: “You loved it! You really loved it!” Since I had so much fun breaking the movie down, you can expect this to be a semi-regular feature, and today I’m following it up with a film I’ve always wanted to dissect: Raiders Of The Lost Ark.

When it comes to summer action movies, there aren’t too many films that hold a candle to the perfectly crafted Raiders. Many have tried, and while some have cleaned up at the box office (Mummy, Tomb Raider

) they haven’t remained memorable past the summer they were released.

So what makes Indiana Jones such a classic? What makes this character one of the top ten movie characters of all time? Here are ten screenwriting choices that made Raiders Of The Lost Ark so amazing.

THE POWER OF THE ACTIVE PROTAGONIST

At some point in the evolution of screenwriting, a buzz word was born. The “active” protagonist. This refers to the hero who makes his own way, who drives the story forward instead of letting the story drive him. I don’t know when this buzz word became popular exactly, but I’m willing to bet it was soonafter Raiders debuted. One of the things that makes Indiana Jones such a great character is how ACTIVE he is. In the very first scene, it’s him who’s going after that gold idol. It’s him driving the pursuit of the Ark Of The Covenant. It’s him who decides to seek out Marion. It’s him who digs in the alternate location in Cairo. Indiana Jones’ CHOICES are what push this story forward. There’s very little “reactive” decision-making going on. And the man is never once passive. The “active” protagonist is the key ingredient for a great hero and a great action movie.

THE ROADMAP TO A LIKABLE HERO

Indiana Jones is almost the perfect character. Believe it or not, however, it isn’t Harrison Ford’s smile that makes Indy work. The screenplay does an excellent job of making us fall in love with him, and does so in three ways. 1) Indiana Jones is extremely active (as mentioned above). We instinctively like people who take action in life. They’re leaders. And we like to follow leaders. 2) He’s great at what he does. When we see Indiana cautiously avoid the light in the cave, casually wipe away spiders, or use his whip to swing across pits, we love him, because we’re drawn to people who are good at what they do. And 3) He’s screwed over. This is really the key one, because it creates sympathy for the main character. We watch as our hero risks life and limb to get the gold idol, only to watch as the bad guy heartlessly takes it away. If you want to create sympathy for a character, have them risk their life to get something only to have someone take it from them afterwards. We will love that character. We will want to see him succeed. I guarantee it.

ACTION SEQUENCES

When you think back to Indiana Jones, what you remember most are the great action sequences. Nearly every one of them is top notch. And there’s a reason for that. CLARITY . Each action sequence starts with a clear objective. Indiana tries to get the gold idol in the cave. Indiana must save Marion in the bar. Indiana must find the kidnapped Marion in the streets of Cairo. Indiana must destroy the plane that’s delivering the Ark. It’s so rare that we see action sequences these days with a clear objective, which is why so many of them suck. Look at Iron Man 2 for example. What the hell was that car race scene about? We have no idea, which is why despite some cool lightning whip special effects from Mickey Rourke, the scene sucked. Always create a clear objective in your action scenes.

REMIND YOUR AUDIENCE HOW DIFFICULT THE GOAL IS

High stakes are primarily created by crafting a hero who desperately wants to achieve his goal. I don’t know anyone who wants anything as much as Indiana Jones wants that Ark. But in order to build those stakes even higher, you want to remind the audience just how important and difficult it will be for your hero to achieve that goal. For example, there’s a nice little quiet scene in Raiders right before Indiana goes on his journey where his boss reminds him what finding the Ark means. “Nobody’s found the Ark in 3000 years. It’s like nothing you’ve gone after before.” It’s a small moment, but it’s a great reminder to the audience. “Whoa, this is a really big freaking deal.”

IGNORE THE RULES IF IT SUITS YOUR STORY

Part of becoming a great screenwriter is learning when rules don’t apply to the specific story you’re telling. Each story is unique and therefore forces you to make unique choices. One of the commonly held beliefs with any hero journey is that there must be a “refusal of the call.” When Luke is given the chance to help Obi-Wan, he backs down, “I can’t do that,” he says. “I still have to work on the farm.” Indiana Jones, however, never refuses the call. And Raiders is a better movie for it. Because the thing we like so much about Indiana Jones is that he’s gung-ho, that he’s not afraid of anything. So if the writers had manufactured a “refusal of the call” moment, with Indy saying, “But I have to stay here and teach. I have a dedication to the university,” it would’ve felt stale and forced. So whenever you’re trying to incorporate a rule into your story that isn’t working, consider the possibility that you may not need it.

GIVE A GREAT INTRO TO YOUR FEMALE LEAD

I can’t tell you how many male writers make this mistake (and how many female writers make this mistake in reverse). You need to put just as much thought into your female lead’s introductory scene as you do your male’s. Raiders is a perfect example of this. Indiana Jones has one of, if not the, greatest introductory scene in a movie ever. If you don’t give that same dedication and passion to Marion’s introduction, she’s going to disappear. That’s why, even though her entrance doesn’t compare to Indiana’s, it’s still pretty damn good. We have the great drinking competition scene followed by the battle with German/Nepalese thugs. The girl is badass, swallowing rum from a bullet hole leak in the middle of a life or death battle! Always always always give just as much thought to your female introduction as your male’s.

ADD IMMEDIACY AT EVERY TURN

The pace of Indiana Jones still holds up today, 25 years later. Not an easy task when you’re battling with the likes of Michael Bay and Steven Sommers, directors who have ruined audience’s attention spans with their ADD like cutting. Raiders achieves this pace not through dizzying editing tricks, but through good old fashioned story mechanics, specifically its desire to add immediacy to the story whenever the opportunity arises. Take when Indy arrives in Cairo for example. The first thing he’s told when he gets there is that the Germans are close to finding the Well of Souls! What?? This was supposed to be a simple one-man expedition! Now he’s in direct competition with a team of hundreds of men??? Because of this added immediacy, the stakes are raised and Indiana’s pursuit of his goal is more entertaining. So always look to add immediacy to your action movie where you can!

IF YOU HAVE A BORING CONVERSATION, INJECT SOME SUSPENSE INTO IT

You are always going to have two person dialogue scenes in your movie. These scenes can get very boring very quickly, especially in an action film. There’s a scene after Indy and Marion get to Cairo where they walk around the city. Technically, we don’t need this scene but it does help establish the relationship between the two, which is important for later on. Now a lesser writer may have sat these two in a room and had them divulge their pasts to each other in a boring explosion of exposition. Instead, Kasdan has them walking around, and *cutting to various bad guys getting in position to attack them.* This adds an element of suspense to the conversation, since we know that sooner or later, something bad is going to happen to our couple. MUCH more interesting than a straight forward dialogue scene between your two leads.

MOVING ON FROM DEATH IN AN ACTION MOVIE

Many times you’ll run into an issue where a major character in your movie dies. Yet you somehow must make us believe that your hero is willing to continue his journey. The perceived death of Marion creates this problem in Raiders. The formula to solve the problem? A quick 1-2 page scene of mourning, followed by the hero being placed in a dangerous situation. The mourning shows they properly care about the death, then the danger tricks the audience into forgetting about said death, allowing you to jump back into the story. So in Raiders, after Marion “dies,” Indiana sits back in his room, depressed, then gets a call from Belloq. The dangerous Belloq questions what Indie knows, followed by the entire bar prepping to shoot him. After that scene you’ll notice you’ve sort of forgotten about Marion, as crazy as it sounds. This exact same formula is used in Star Wars. Obi-Wan dies, we get the quick mourning scene on the Falcon, and then BOOM, tie fighters attack them, seguing us back into the thick of the story.

INDIANA’S ONE FAILURE – CHARACTER DEVELOPMENT

Raiders is about as perfect a movie as they come. However, it does drop the ball on one front. Indiana Jones is not a deep character. Now because this is an action movie, it doesn’t really matter. However, I’d argue that the script did hint at a character flaw in Indiana, but ultimately chickened out. Specifically, there’s a brief scene inside the tent when Indiana discovers Marion is still alive. This presents a clear choice: Take Marion and get the hell out of here, or keep her tied up so he can continue his pursuit of the Ark. What does he do? He continues his pursuit of the Ark. This proves that Indiana does have a flaw. His pursuit of material objects (his work) is more important to him than his relationships with real people (love). However, since this is the only true scene that presents this flaw as a choice, it’s the only time we really get inside Indiana’s head. Had we seen a few more instances of him battling this decision, I think Raiders would’ve hit us on an even deeper level.

Tune in next week when I dissect Indiana Jones and The Kingdom Of The Crystal Skull!

Winning….

Genre: Thriller

Premise: (from IMDB) Centers on a psychologist, and her assistant, whose study of paranormal activity leads them to investigate a world-renowned psychic.

About: Red Lights is the follow-up effort of Rodrigo Cortes, the director of Buried. Not only is Cortes directing the movie, but he also wrote the screenplay. The cast is a good one, including Cillian Murphy, Sigourney Weaver, Robert De Niro, and new breakout star after her performance in Sundance darling, Martha Marcy May Marlane, Elizabeth Olsen. The movie started shooting a couple of weeks ago.

Writer: Rodrigo Cortes

Details: 124 pages – October 2010 draft (This is an early draft of the script. The situations, characters, and plot may change significantly by the time the film is released. This is not a definitive statement about the project, but rather an analysis of this unique draft as it pertains to the craft of screenwriting).

One thing I worried about after reading Buried was, “Will an audience be able to handle staying in a single enclosed space for the entirety of the movie?” The answer to that, of course, would depend on the director. So when I finally saw the film and spent 90 minutes in a coffin never once wishing we were cutting to an exterior location, I knew they picked the right guy. It’s probably not a surprise, then, that Cortes has found himself as one of the more in-demand young directors in Hollywood, evidenced by the sweet cast he’s secured for this project.

But then I found out Cortes would also be writing the movie. Directors, by their very nature, tend to put more emphasis on the visual than the written word. They’re thinking of crafting that perfect shot or that unique sequence nobody’s ever seen before, not rewriting the living hell out of a plot point until it sings on the page. There are exceptions of course (early Cameron Crowe, early James Cameron, Tarantino) but I always feel like we’re getting the short end of the writing stick when a director writes his own script, and although I love to be proven wrong, it usually doesn’t happen.

But hey, I was willing to give Red Lights a chance. The premise sounded cool and his debut American movie worked. So why not?

59 year old Dr. Margaret Matheson has dedicated her life to debunking psychics, those fakers who claim to have otherworldly powers, who are able to peek into the unseen dimensions that exist just outside our realm of consciousness. If you say you saw an alien, can talk to the dead, can read minds, can move objects with your brain, Matheson will calmly walk through your door and prove that you can’t.

She’s accompanied by 33 year old physicist Thomas Buckley, who has a little more faith in the supernatural than Margaret, but is quietly shocked as again and again Margaret is able to expose every “real” case they encounter.

While the two debunk cases including a haunted house (that turns out to be one of the daughters banging on the wall) and a faith healer (who’s being fed information about his victims through an earpiece), the most popular psychic in history, the blind Simon Silver, is gearing up for a comeback. The man used to be an iconic figure, one of the only popular psychics to have ever stood up to scientific scrutiny. When he books a series of shows, Thomas is eager to go after him. If they can prove that this guy is a fraud, they can basically prove that the whole field is a sham. But for whatever reason, Margaret refuses to mess with Silver. There’s something different about this one, something that doesn’t quite add up.

But when Silver finally agrees to allows his powers to be scrutinized by top level scientists to once and for prove he’s not a sham, Thomas will do anything to get on the committee, as he suspects Silver will try and manipulate the results. However when Silver gets wind of this man’s personal vendetta, he becomes fixated on him, and Thomas quickly realizes that he may be in over his head.

Red Lights is a funky little thriller that captivates you when it’s working and baffles you when it’s not. Imagine Fringe mixed with The Prestige and you have a pretty good idea of the script. I think the big problem here is that the story is weighed down by too many unneeded scenes, scenes that go on for too long, and scenes that are redundant. For example, you really only need one scene to establish your hero’s abilities – in this case the scene where she exposes the fake haunted house. But we also get two additional scenes reinforcing this ability. This would be fine if they pushed the plot forward in some way. But they do not. One of those scenes in particular, when they go to the preacher’s sermon, just goes on forever. It could’ve accomplished the same thing in half the time but refused to end. These are things pure screenwriters will endlessly work out until they get it right. But here, the mantra seems to be “more is more,” and as a result, it takes us a really long time to get to the plot.

In fact, I would say that the plot (take down Silver) isn’t revealed until halfway through the script . Complicating this is that it’s never entirely clear what the motivations of our main characters are for doing this. Margaret has an experience from her past that sort of explains why she’s so intent on exposing these people, but she doesn’t want to mess with Silver, so it’s not really applicable. Thomas, on the other hand, never explains why he needs to take down Silver so bad, which is problematic, since he eventually becomes the driving force behind the story. If we’re unclear on why our main character is doing what he’s doing, your story is in some trouble.

But all is not lost. What Red Lights loses in the structural department, it finds in the mood/tone department. The entire script is eerie, especially the character of Silver, who we’re constantly trying to figure out. It’s a nice little dance. Silver seems to not want to be exposed for something. Yet if he’s afraid of being exposed, how is he able to make all these otherworldly attacks on our heroes? That simple question drives our need to find out how this ends.

In fact, I would say Silver is the key to this screenplay working. Much like both characters in The Prestige or Edward Norton’s character in The Illusionist

, that central mystery of “How does he do it?” implores us to watch on. We want to know how Silver is pulling it off. So even though the story takes too long to get going, and gets bogged down in redundancy, the power of that question keeps us intrigued.

And really, this is what writing comes down to. How do you keep the audience’s interest? You should be able to randomly point to any page in your script and explain why, at that very moment, the audience will still be interested in what’s going on. Is it because you desperately want the character to achieve his goal (get the Ark in Indiana Jones), is it because you desperately want two people to be together (When Harry Met Sally

), or is it powerful mystery (Is Silver real or not?). That just might be enough for your script to work.

Do I have some issues with it? Sure, of course. Besides the issues I mentioned above, this is yet another script where there’s very little conflict going on in the central relationship (Margaret and Thomas). But Red Lights is a spooky script with an intriguing antagonist that has enough mystery and a unique enough story rhythm to keep you guessing til the end. I’d say it’s worth the read.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: When I see a script that’s this long (125 pages), the first thing I think is, I’ll bet anything there’s too much fat here. But I always ALWAYS allow the writer to prove me wrong. If I read that first act and the writer isn’t reintroducing his character three times, if he isn’t staying in scenes for 2-3 pages too long, if he’s not writing scenes that don’t push the story forward, if we get to the inciting incident early, I gladly tip my hat and say, “Okay, you proved me wrong.” But after reading hundreds of 125+ page screenplays, you know how many times that’s happened? Once. These huge page counts go hand in hand with these mistakes. I mean, do you really think it’s a coincidence that in a 125 page screenplay, the plot doesn’t emerge until page 60? So if you’re going to write a 125 page script, prove that you need all 125 of those pages! Don’t rewrite the same scene in a slightly different location ten pages later. Don’t write scenes that establish the same things about your character you’ve already told us. Don’t write scenes that aren’t pushing the story forward. You have to be sparse. You have to be diligent. You have to get to your story quickly. Cortes has a little bit of an excuse because he may be shooting stuff he knows he’s going to cut, but in the spec world, you don’t have that luxury.