Genre: Thriller

Premise: A contagious and deadly disease confounds an international team of doctors who try desperately to contain it before it becomes a worldwide plague.

About: Contagion sold earlier this year with Steven Soderbergh attached to direct. Scott Z. Burns, the writer, was a producer on The Inconvenient Truth and is best known for writing The Bourne Ultimatum. He also penned The Informant. Set to shoot later this year, Soderbergh once again shows he can bring the talent. Matt Damon, Kate Winslet, Jude Law, Marion Cotillard, Lawrence Fishburne, and Gwyneth Paltrow are all a part of this amazing cast.

Writer: Scott Z. Burns

Details: 131 pages – January 14, 2009 draft (This is a very early draft of the script. The situations, characters, and plot may change significantly by the time the film is released. This is not a definitive statement about the project, but rather an analysis of this unique draft as it pertains to the craft of screenwriting).

Steven Soderbergh continues to remain a curious figure in Hollywood. He never does what the studios want him to do and that’s given us cinephiles some brilliant little films and – let’s be honest – some really shitty ones. “Sex, Lies, and Videotape” is still one of my favorite indies of all time (some say it’s the movie that officially started the indie movement). I revisited it recently and while our shock-a-minute society had dulled my senses to some of its more “risky” moments, it’s still one of the best pure talking heads movies I’ve ever seen.

Staying true to form, Soderbergh refuses to explore his virus-thriller, Contagion, via conventional storytelling means, nixing the “hero with personal issues to overcome,” angle and going for more of a cinema verite, documentary approach. This would make sense as Soderbergh loves shooting his films in the that gritty unflattering mold. No doubt it gives the script a unique edge, as we’re pulled into the world of disease control as if we’re right there making the decisions with the characters.

It’s Thanksgiving week. Beth Emhoff is coming back from work in Hong Kong. At O’Hare airport, she begins to feel sick.

Li Fai, a worker at a casino, is heading to Hong Kong on a ferry. He, also, is feeling weary.

Irina, a Ukrainian model, doing her best to push through a photo shoot, feels like she’s going to pass out.

Beth makes it home to her husband, Thomas, and her son, Clark, where she plans to sleep off the flu-like sickness and regroup in the morning. Well she gets to do plenty of sleeping all right. In Heaven. Yes, poor Beth goes into a seizure and ends up dead at a hospital an hour later.

This leaves us with her husband Thomas, whose son has also been feeling lousy ever since mom got home. Clark’s health deteriorates at a terrifying pace and soon the unthinkable happens. He too dies, leaving a shocked Thomas, and a lot of unfinished coloring books, all alone.

Panic mode hits Clark’s school, with teachers and parents wanting to close the school down in case the deadly sickness is contagious. Eventually Dr. Ellis Cheever, a viral specialist, is called in. Once he gets whiff of the danger, he immediately isolates Thomas in quarantine while he tries to find out what the hell killed a mother and a son in such a short period of time.

Oh and wouldn’t you know it, both Irina, the model, and Li, the ferry passenger, die as well. A link is found between Beth and Li and before you know it, International CDC doctors are scrambling to figure out just how concerned they should be. What first looked like an isolated tragedy, is quickly becoming a viral outbreak of Mega-Death proportions.

For a virus this potent, you have to know where it originated before you can start building a plan to stop it. So the CDC and international authorities begin pouring over thousands of hours of video footage in the buildings Beth frequented while she was in Hong Kong.

But the clock is ticking. This virus is spreading like wildfire and soon there are death clusters in Western Europe, Hong Kong, and the U.S. This is starting to look like the big daddy, the Black Plague of the 21st Century.

In the meantime, a conspiracy theorist blogger named Alan Krumwiede starts up a rumor that the virus is spread through water. This sets the world into mass panic mode, thrusting it perilously close to the tipping point. If the public believes that the government won’t save them, there will be a run on the banks, the grocery stores, the gas stations. Society will cease operating.

Every second that passes in which the world’s top doctors don’t figure this out, is one second closer to that worst case scenario.

As you can see, Contagion is a look at what would really happen if a modern day plague broke out. Gone are character motivations, intricate sub-plots, backstory or the 3-Act structure. Contagion bounces around to whichever government or medical body would be dealing with the problem in real life. So even though we assume that Thomas, losing his wife and son, will be our guide in the film, his character disappears off the face of the earth after the quarantine scene. It’s like he was never there to begin with.

The script survives this odd choice, though, due to its Titanic-sized plot engine. I mean we’re talking about the end of the world here. Will they or won’t they stop the virus before it’s too late? It’s hard not to get wrapped up in that. And one of the unique things Contagion has going for it is BECAUSE it favors reality over traditional storytelling, we almost believe that it’s the world we inhabit that’s in danger, and not some Michael Bay perfectly lit idealized New York City.

The script also does a nice job spinning the old attic noodle. You realize afterwards that we are so underprepared for an event like this, even though these super-killers have popped up every 80 years since the beginning of time. It’s terrifying to realize that under the wrong circumstances, our society could cease functioning in as little as two weeks. There’s also some very poignant commentary on big business and the way vaccines would be distributed if this really went down. With so much money on the table, you can bet your ass people are going to be dying while they figure out the percentages. All of that stuff was really fascinating.

The big problem with Contagion though, is that the ending is mushy. We spend the entire screenplay building up this virus to DEFCON 5 status, and then we get this tame middle-of-the-road resolution to it all. It’s hard to explain without spoiling it, but there’s no dramatic conflict in the climax. It just sort of…works itself out. And a part of me commends it for staying true to its “real life” aspirations, but in this case, real life was a really fucking boring option. I guess I wanted more of an “all or nothing” finish and since this is an early ’09 draft, maybe they’ve gone ahead and added one. But this ending was so unsatisfying it really hurt my opinion of the script.

There were some other minor things that bothered me as well. Krumweide was a dumb character, the only cartoonish aspect of the entire piece. And while the lack of character development didn’t bother me at first, as we got towards the end, I was really wanting to latch on to someone – ANYONE – in order to feel something. There are no heroes here. Just real-life faces doing their jobs. I only wish I’d known more about those faces so I could care about them. Add a disappointing ending to this and I can’t give this draft of the script a passing grade. I’ll just hope Burns and Soderbergh worked out all these kinks since. Because this project has a lot of potential.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: I have a theory about why this ending didn’t work. The climax of almost every good movie is tied to the main character’s inner conflict (or “thing” as I called it in yesterday’s “What I Learned” section). So in Inception, Cobb has to overcome his issues with his wife in order to finish the job with Robert Fischer. In The Matrix, Neo has to believe in himself before he can stop the bullets and defeat the agents. Since there isn’t a single character developed in Contagion, since we don’t know what’s going on under anyone’s surface, it’s hard to construct an emotionally satisfying ending. Unlike Cobb and Neo, there’s nobody here with issues to overcome. That means the plot has to do it all by itself, and I don’t think any plot can hold that kind of weight. As a result, Contagion folds in the third act. So remember that a good climax usually involves a main character who’s finally overcoming his flaw. It’s by no means the only way to write your climax, but it usually works when done well.

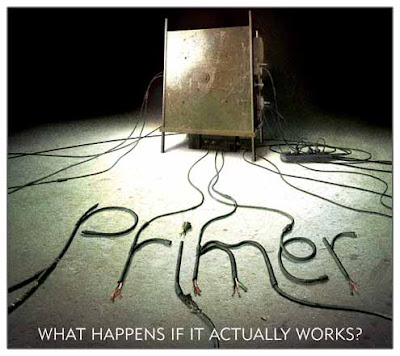

I’m taking a break today and bringing in Aaron Coffman to review a script that you couldn’t get me to read with an AK-47 pointed directly at my nose. 244 pages?? That means at page 120 you’re not even halfway finished! When James Cameron says your script is too long, that’s when you know your script is too long. But that’s why I’m bringing in AC, a Primer fan who wrote one of my favorite scripts of Amateur Week, The Translation. He’s read this thing not once, but twice, sacrificing his entire 2009 to do so. So I thought the least I could do is give him a platform to tell us about it. Here’s Aaron with his review of Shane Carruth’s “A Topiary.”

Genre: Sci-fi?

Premise: This may be the first script in Scriptshadow history that can’t be described in premise form.

About: Shane Carruth burst onto the scene with his low-budget sci-fi brain teaser “Primer,” which won the grand prize at Sundance in 2003. Strangely, Carruth doesn’t have a single credit to his name since that film (although he may have done some uncredited writing work). If I had to guess why this is, I’d say it’s because this film (which he’s trying to make himself) sounds like it would cost 150 million dollars, which may be a tad ambitious when the only other budget you’ve worked with is 10,000 bucks. As a side note (this is Carson here), I went to a question and answer session after a screening of Primer in 2004, and I remember Carruth being very nice and quite overwhelmed by the Hollywood Machine. He told us that he had no idea you were supposed to go into meetings with ideas for future movies ready to pitch. His thinking was, “I just spent the last 3 years making this movie and it’s finished. Why do you want me to talk about something I haven’t even written yet?” I always remember that and thinking afterwards, “You know what, he’s got a good point.”

Writer: Shane Carruth

Details: 244 pages

Let’s just get this out of the way, right here and now, and then we can get on with things… A Topiary is 244 pages long and there is a very good chance I’m not smart enough to understand what it’s really about. I’ve read it twice now, and I’m still not sure exactly what’s going on.

The script begins with a 68 page first act in which Acre Stowe, a city employee, has been tasked with finding the perfect spot for a first response facility. The idea is that they want to build this building close to where all the accidents happen to cut down on response time. By taking data from the past seven years he’s come up with a weighted average that pin-points the spot where the contractor should build.

Lobbyists aren’t happy with the location and give Acre data that they suspect will get a location more to their liking. And yet, when he breaks it down and plugs their data into his equation, he comes up with the same location.

An intersection.

This leads him out to this specific location, and it’s here where he sees a starburst glistening off a skyscraper. And it’s within this starburst that he sees a pattern. A pattern that he starts to see everywhere. He begins following the pattern to different locations around the city, marking each location on a map. And eventually, realizing that the locations on the map create a design that looks like the starburst.

The journey blossoms as the first act spans around eight years or so and Acre meets and joins a cult-like group of scientists who are investigating the same phenomenon. To go into more detail would be counter-productive as it’s not entirely clear what they’re looking for or what they find. In fact, the first act ends with Acre resigned to the fact that they’ve hit a dead end.

Acre’s story ends here, and we pick up with ten boys, aged 7-12, who discover something called a ‘Maker’ which ejects strange discs. Without much explanation the boys discover that the discs have strange abilities and eventually the boys can build rocket-like toys out of them and control their flight with small ‘controller’ discs. By holding or wearing these controller discs they merely have to yell, “launch” and the rockets take flight.

Then slowly, as they toil with their rockets they discover that they can in fact create creatures with these discs and control their actions. The controller disc now acts like a Wii remote…

…I think I’m going to stop here, because I don’t think I can clearly describe what comes next. Let’s just say that over the next 176 pages the boys learn to make more sophisticated creatures, they discover the discarded pieces from the creatures they created have bloomed into a fort, and then a war breaks out between them and what I think are the scientists from the opening act. And it’s during this war that the boys use their creatures like that giant war elephants in that last Lord of the Ring movie. Beyond that, I’m still confused as to what exactly happened.

Oh, except I do know that the boys eventually make a full-scale flying dragon. That part was pretty clear.

Now despite my confusion, and inability to properly describe what happens with much detail, I can say that I really hope Carruth gets to make this film. As a fan of Primer, there were a lot of things that I loved about that film that he brings back here.

First, Carruth has talked in the past about how All the President’s Men was a big influence on Primer. More specifically the idea that you don’t have to explain everything to the audience as long as the two characters who are talking onscreen seem to know exactly what they’re talking about. In A Topiary Carruth does the same thing both with Acre in the opening act and again with the boys. They clearly know what they’re after, but it’s not made entirely clear to the reader just what that is. While some might find this annoying, in this case I found it interesting and it helped keep the story moving at a clip and kept my confusion at bay.

While reading this script I couldn’t help but think of the pacing of Magnolia and how the sequences almost had an operatic quality to them. Each sequence would start out slow and then build and build and build and then move suddenly into the next sequence. I think this helps keep a long script feeling energized as it moves towards its conclusion. It really helped in this instance as the script was, well, long.

Something else Carruth does here that he did very well in Primer is to sound like he knows what he’s writing about. In Primer it felt like everything the characters were doing was based in real-world research and that is the case here as well. In the opening act I felt that Carruth had taken his time to do his research, not just in the fantastical details, but even the smallest details. For instance, when Acre interacted with the other municipal workers it sounded real. There was a short hand to the way the characters spoke to each other.

“Look, we’ve gotta get the –”

“Yeah, it’s on its way, has he called light and power –”

“This morning. Paperwork is on my desk. Just need your signature on the I-9 –”

Now, I personally felt there were some issues with the script, specifically there were a lot of names given to the strange objects the boys come in contact with and I had a difficult time keeping them all sorted out, especially as the story went along. Each time something was given a name, and then became a big part of the story I had to step back for a moment to take inventory of everything that had been introduced to make sure I still remembered what it all did. The ‘Maker’ did this, the ‘funnel’ did this, the ‘governor’ did this’ the ‘petals’ did this, the ‘flowers’ did this, etc, etc…

Lastly, I could probably discuss the formatting that Carruth used, since it did feel as if it had been written in MS Word, but ultimately because Carruth is directing this, the format isn’t really a major concern.

Let me just end this mess with restating that I hope Carruth finds the money to make this film. The script can be frustrating and it can feel long at times and it can lose you at others, but it also feels like it was written by someone who knows exactly what they want to do with it and have a clear vision on what it should look like in the end. It’s an original work and boy do we need more of those right now.

[ ] What the Hell Did I Just Read?

[ ] Wasn’t for Me

[x] Worth the Read

[ ] Impressive

[ ] Genius

What I Learned: If you’re writing a script that you plan on directing yourself, then you can pretty much do whatever you want. Sure, eventually someone will need to understand what you want to do so they can give you some money, but until then, write the script however you want. If you’re writing a spec, I don’t think this should be your blueprint. If you are trying to secure an agent or make a sale there are ways to write this story in a more traditional way. That’s not to say you can’t be original when writing a spec and it’s not to say you can’t try and do something different, but if you want that agent, handing them a 244 page script probably isn’t the best idea. I imagine if this script found its way onto the desk of a reader, that person would get maybe halfway down the first page before tossing it into the recycling bin — and I’m not even talking about the shred-only box that contains Amy Pascal’s receipts from her last trip to Vegas — I’m talking about the blue bin for bottles and plastic cups that sit next to the dumpster out back.

Genre: Thriller/Contained/Drama/Post-Apocalyptic

Premise: A married couple is vacationing on the island where they spent their honeymoon, when a man in military fatigues washes onshore, claiming the end of the world is coming.

About: I thought that this sold last week but it was actually sold much earlier in the year. Last week was the announcement that Jason Isaccs was being replaced by Inception alum Cillian Murphy in the lead role. Thandie Newton will also star, and co-writer Carl Tibbetts will make his directing debut. Many are calling the film “the next Dead Calm,” which is high praise, as Dead Calm is one of my favorite thrillers.

Writers: Carl Tibbetts and Janice Hallett

Details: 91 pages – March 17, 2010 draft (This is an early draft of the script. The situations, characters, and plot may change significantly by the time of the film’s release. This is not a definitive statement about the project, but rather an analysis of this unique draft as it pertains to the craft of screenwriting).

I strolled into a rental store for the first time in four months last night listening to the audiobook of The Girl Who Played With Fire, the second novel in the now famous “Girl With The Dragon Tattoo” trilogy. I was on the chapter about math. I did everything in my power to escape math once out of college, yet there it was, being piped down my eardrums by Martin Wenner, the audiobook reader for the Dragon Tattoo series, who was explaining to me, in a thick English accent, the root of the square root. I was confused and discombobulated by the conflux of these events, which may explain how I walked out of the store with a copy of “The Losers,” a movie with the cinematic ambition of an eighth grader with a flip phone at the skate park.

As I watched this movie, I was surprised to realize that technically, it was well-written. Sure the dialogue was way corny and it tried uber-hard to be the kind of film you quote with your buddies on a roadtrip, but the thing was so structurally sound you could practically see a graph of Blake Snyder’s beat sheet behind it. It was a reminder that structure is only half the battle. Your choices still need to be original. Your dialogue still needs to be fresh. A dirty little secret is that workmanlike gets it done when you’re an established professional, but when you’re an amateur, more is required in order for others to take notice.

I bring this up not because The Losers and Retreat are similar in any way, but because Retreat is a contained thriller, and there are so many of these flooding the market, you need to figure out ways to elevate the material beyond the obvious (which The Losers wasn’t able to do). Now assuming you’re a competent screenwriter and know your 3-Act structure, the place this happens is in the choices you make for your story. Are they different? Are they new? Are you challenging both yourself and the audience? There’s hundreds of directions you can take a story about a vacationing couple who get word that the world is ending. So did Tibbetts and Hallett merely get to the finish line, or did they come up with an original exciting thriller with loads of surprising twists and turns? Let’s find out.

Martin and Kate are a well-off Irish married couple in their 30s. The two are heading to Dinish Island, a tiny private island off the Irish Coast where they spent their honeymoon together a decade ago.

But it’s evident early on that something is broken in this relationship. Kate seems more interested in talking to the tugboat owner, Doug, on the way over, than she does her own husband. In fact, the more we get to know these two, the more we notice how rare it is for Kate to even *look* at Martin.

And that’s because Martin, a hardcore workaholic, was too busy working to answer Kate’s distressed call 8 years ago when she had a miscarriage. Kate still hasn’t forgiven him for not being there, and hasn’t forgotten that Martin never wanted the child in the first place. This vacation is a last ditch effort on Martin’s part to save this marriage, a venture that’s looking less and less likely by the minute.

Retreat eases into its story slowly – maybe too slowly – as Martin and Kate perform a number of couple-related tasks under a thick cloud of tension. And just when you want to personally kick the story in the behind to move it along, an unconscious man washes ashore with military fatigues and a gun. The two hurry him into the house to nurse him back to health, only to learn, according to him, that a pandemic has swept across the globe like wildfire. Pandemic, if you don’t know, is the deadliest of the “demics” as it’s the kind that spreads through the air. And this one is a doozy. Catch it and you’ll be dead within 48 hours.

The man, Corporal Jack Corman, a member of the Royal Marines, dutifully starts boarding up windows and doors without consulting the couple, preparing for “when they come.” “They” is in reference to the survivors, who Jack predicts will be catching rides over to this island any minute now, in search of safety. And since they’ll probably be infected, it’s their job to make sure they don’t get in the cottage.

But Martin and Kate note an inconsistency in Jack’s comments and logic. There’s something off about the man, and it causes them to question whether he’s locking other people out, or locking them in. Unfortunately, with everything happening so fast, and no previous experience for “what to do when there’s a pandemic and a crazy man runs into your home and starts boarding everything up,” by the time Martin and Kate realize he might be dangerous, they’re already locked inside. With their only communication to the outside world an old CB radio that barely works, Jack becomes their only source to the outside world.

So when I’m determining whether something is elevating the material or just making the obvious choices, the first thing I look at is “Am I able to predict where this story is going?” I may not know exactly what’s going to happen, but if I generally know the twists and turns, that’s a bad sign. Obviously, you’re not being original if the reader can predict what’s going to happen.

Retreat, unfortunately, falls into this rut. For the first 50 pages or so, I knew every beat, every twist, every surprise, and while I wouldn’t say I was bored, I was disappointed that things were moving along so predictably. But I’ll tell you where the script saved itself. At a certain point, we think we know whether Jack’s lying or not. Then we’re not so sure. Then we’re sure again. Then we’re not so sure.

Retreat places that question front and center in the story: Is there a pandemic or not? And it keeps going back and forth on whether there is. After flipping back and forth so much, we really have no idea what to believe. And because we want to know the answer to this mystery, we’re compelled to read til the end. That alone makes this script worth the read.

But Retreat still suffers from the same thing a lot of these low-character contained thrillers suffer from. With only a single couple’s problems to explore during the second act, there’s a lot of extra time to fill, and so we’re given these scenes – particularly between Jack and Kate – that are intense and racy but lack a certain truth to them. Instead of servicing the story they feel like they’re trying to make up for the lack of it. I kept asking, “Why is Jack doing this? What’s his plan here?” And I could never come up with a satisfactory answer, which implied that it was just filler until we got back to the story again. I didn’t think these scenes were bad, but they definitely felt forced, and pulled me out of the script.

I also thought the writers missed a huge opportunity. This story is essentially about a woman who wanted children then lost a child, and how that event affected her marriage. That theme keeps coming up again and again. So why wouldn’t you have Kate pregnant again? How much more intense would this be if they were reliving the very thing that tore them apart in the first place? With her pregnant, possibly due soon, every problem here would be magnified times a thousand. It would also give the story more places to go.

I have to give it to the writers though. It’s so easy to wrap these stories up in a nice little bow. But Tibbetts and Hallett don’t screw around, leaving us with a finale that’s both shocking and disturbing. Retreat doesn’t rewrite the book on thrillers by any means, but the storyline keeps you guessing enough to make it worth the investment.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: There’s a sizable percentage of writers who are resistant to any kind of screenwriting academia. I might say to someone, “Your main character needs a fatal flaw,” and they’ll reply with a scoff. “Don’t throw that screenwriting mumbo-jumbo at me,” their eyes say. I get that. Everybody has their own process. So let me take the technical side out of it and say it this way: every character should have a “thing” going on. Everybody’s got a “thing.” My friend Dan’s thing is that he’s obsessed with women, to the point where it’s ruined a marriage and a couple of other great relationships he’s had. My friend Claire’s thing is that she refuses to rely on other people for help. She has to do everything herself, even when at times it’s impossible. Kate’s thing here is that she can’t forgive her husband for putting his work before her. Think about all the friends in your life. You can probably break all of them down into having that one “thing” that identifies them. This “thing” is what you use your screenplay to explore. Sure this concept is about a deadly virus that could potentially end human existence. But really this script is about a woman trying to come to terms with what her husband did to her, forgive him, and move on. Once you identify what your main character’s “thing” is, you can use your screenplay to explore it. If you’re not doing that, I got news for you, you’re going to have a hard time writing a good screenplay.

This week has an interesting ring to it. I’ll be reviewing two scripts that deal with the same subject matter in very different ways, one with a well-known director attached and one that sold just last week. We also have a guest reviewer coming in to review Shane Carruth’s (Primer) long in-development project, Topiary, which I think is something like 200 pages long. I don’t know anything about it but you basically have to be a genius to write a 200 page script, or really bad at formatting, so we’ll see. Friday is still undecided but I’m sure I’ll find something to read. Right now, Roger reviews the recently sold, “Die In A Gunfight.”

Genre: Drama

Premise: A high society outlaw falls in love with the daughter of his father’s rival, endangering not only their reputations, but their lives.

About: In one of those stories that’s sure to bring out the jealousy and set the bar very high for this writing team, Andrew Barrer and Gabriel Ferrari sold this script straight out of NYU. “Die in a Gunfight” is next in line for Zac Efron. A project with a risky role, this may be Efron’s meal ticket to cinematic coolness.

Writers: Andrew Barrer & Gabriel Ferrari

Details: June 2010 draft – 109 pages (This is an early draft of the script. The situations, characters, and plot may change significantly by the time of the film’s release. This is not a definitive statement about the project, but rather an analysis of this unique draft as it pertains to the craft of screenwriting).

Zac Efron seems to be smartly cultivating his dapper Disney star image while cautiously stepping outside his bubblegum box to show the rest of us that he’s more than just a debonair pretty face. Do I think it’s a stretch to compare him to Johnny Depp? I don’t know, but I present you with the John Waters connection: Depp eschewed expectation and chose Water’s Cry-Baby over all the other pap passed his way, perhaps paving the way for someone like Efron, who starred in a more mainstream friendly rendition of Water’s Hairspray. While Depp didn’t seem to care what people thought of him, Efron appears to be considering the ramifications of career suicide.

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

On the last Friday of every month, I choose an amateur script submitted by you, the readers of the site, to review. If you’re interested in submitting for Amateur Fridays, send the genre, the title, the premise, and the reason I should read your script to Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Note that your script will be posted online and that you shouldn’t submit if you’re allergic to criticism. :) This month’s script is The Assassination Of George Lucas by Aaron Michael Thomas.

Genre: Comedy

Premise: When George Lucas announces a third trilogy, Mac and his group of ragtag friends hatch a plan to assassinate him in the name of preserving the purity of Star Wars.

About: This is the third amateur script in my monthly Amateur Script review series.

Writer: Aaron Michael Thomas

Details: 105 pages

So why did I choose The Assassination of George Lucas over all the other entries for Amateur Friday? Well duh, because the title is “The Assassination of George Lucas!”

But seriously, the title made me smile. And the premise made me laugh. Sometimes that’s all it takes. When you read a lot, there are periods when you want to get away from the serious stuff and just rattle the belly a little bit. I needed some belly-rattlin.

The Assassination Of George Lucas is about four friends: Mac, our conflicted hero, Sarge, the result of a one night stand with a nameless army Sargent, Casey, a home schooled Star Wars nut, and Joanna, who became a lesbian after seeing Princess Leia in Return Of The Jedi.

These childhood friends endure the same devastating disappointment all of us went through when we sat through the debacle known as the prequels. With cinematic perfection forever ruined, the group tries to come to terms with their favorite movies ever never being the same.

And then the unthinkable happens. At Comic-Con, George Lucas makes a surprise appearance to announce that he will be making a third trilogy – episodes 7, 8 and 9. Within minutes, Star Wars costumed geeks are staging a protest. But Mac is so sickened by the announcement, he’s thinking of something much more dire. If Lucas were to make a third trilogy, it would destroy the memory of Star Wars forever, and Mac can’t risk that. Hence, the only way to save Star Wars…is to KILL GEORGE LUCAS.

So he and his buds draw up a flimsy plan to drive up to the Lucas Ranch and poison the goitered one. Along the way they run into a slew of people, including a real life bounty hunter, a frantic Mark Hamill, and a long in hiding Lawrence Kasden. In the meantime we see that Lucas has become so reclusive and paranoid that he can’t even go to the bathroom without body guards. This is a man who will be hard to kill.

There’s some funny stuff in this script. My favorite character was Casey, who’s the only person on the planet who loves the prequels (the guy incorporates Jar-Jar quotes into everyday conversation). In a world where hating on the prequels has become as ubiquitous as pictures of Zac Efron on Perez Hilton, it was funny to watch a character who unapologetically loved them. I also loved the Lawrence Kasdan stuff, as it’s well-known that Lucas didn’t exactly flip over Kasdan getting so much credit for Empire Strikes Back. Seeing him holed up so that Lucas can’t get to him was pretty funny.

The rest of the stuff is hit or miss. There’s a trivial recurring joke about gummy bears, a random scene dedicated to observations about Super Mario Brothers, and probably my least favorite bit, George Lucas being an alienated asshole.

When you write a comedy, you want the jokes to be fresh. And Lucas being a reclusive dickhead has been done to death. I think there’s even a South Park episode dedicated to it. I was hoping for a more complicated original take on the character, not unlike what’s done with Casey. For example, what if Lucas was actually the nicest guy ever? What if they got there and were all ready to kill him and he made coffee for them and sat them down and started telling them stories? How are you going to assassinate the nicest guy ever? That’s a butchered “off the top of my head” idea and I’m not saying it’s great, but the point is, we needed something fresh here.

But the real problem with The Assassination of George Lucas runs much deeper, and that’s the characters. None of these characters have any substance. They have no flaws, no problems, nothing they’re trying to overcome. Each character is exactly the same at the ending as they are at the beginning. And that’s not going to cut it in a comedy spec.

Take the characters in the recently reviewed “Crazy Stupid Love,” for example. Jacob (the womanizer) is emotionally incapable of opening up to women so he engages in an endless streak of one-night stands, not realizing that it’s making him miserable. Watching him resist conquering that flaw is what made his character so interesting. Or take Cal (Steve Carell’s characer), who’s trying to come to terms with his wife leaving him. He doesn’t know whether to embrace the singles scene or fight to get his wife back. In both cases, the characters are fighting an inner battle. None of the characters here are battling anything. In fact, three of the characters are built on a joke. Casey is home-schooled, Sarge is a one-night stand, and Joanna turned into a lesbian after seeing Princess Leia. That’s as deep into the characters as we get. And Mac, our protagonist? His big problem is that he wants to preserve Star Wars. I’m sorry but that’s just not deep enough to keep us engaged for 2 hours.

Instead, what if Mac had a choice tugging at him? What if he’s at a point, 26 or 27, where he has an opportunity to take a job, to start being an adult with responsibilities, or continue this arrested development lifestyle where he’s obsessed with a children’s movie. Now there’s something actually going on with Mac. He has a choice. He has depth. If you want to see this exact flaw in action (and done well), rent The 40 Year Old Virgin and pay attention to Steve Carell’s character.

Another problem I had was that the script didn’t take advantage of its premise. If you look at a movie like Fanboys, which covers similar terrain, there were all these moments where Star Wars serendipitously intruded upon their journey, leading to a lot of funny in-joke situations. The Assassination Of George Lucas is actually about a piece of Star Wars – the prequels – that hasn’t been explored in cinema extensively. There’s a TON of funny situations Thomas could’ve drawn from these movies but instead we keep focusing on the old stuff. For example, why are we bringing in Mark Hamill, who’s already been done to death? Instead, what if they run into Ahmed Best, the actor who played Jar-Jar? Let’s look at how that role ruined his life and how he hates Lucas as a result. What the hell is Jake Lloyd doing nowadays? Maybe he’s a drugged out misfit who actually thinks he’s Darth Vadar. There’s a moment here where our characters walk into a car dealer. Why not make the dealer like annoying nonsensical Watto? In other words, let’s make their journey to kill Lucas turn into their own Prequel Hell. The current comedic choices here are too obvious and deal with territory that we’ve already seen. Let’s explore something new.

The final issue here is that The Assassination of George Lucas probably couldn’t get made. It paints Star Wars and Lucas in a negative light and even though Lucas would whore out the Star Wars brand to flesh lights if it added to the bottom line, the one thing he does still care about is his personal image, which The Assassination of George Lucas…well…assassinates. That would mean you’d have to make this movie without any Star Wars paraphernalia whatsoever, which I don’t think is possible. That’s not to say all is lost, however. Pretty much all scripts are calling cards anyways, so if this made the right people laugh, it could open the door to a career.

The Assassination of George Lucas was a cute script. But if it’s going to compete in the ultra-competitive spec comedy market, it will need to dig deeper.

Script link: The Assassination Of George Lucas

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Your comedies, even the goofiest ones, should contain some sort of theme – some sort of statement you’re trying to get across with your story. When I finished The Assassination of George Lucas I felt…empty. Without a larger statement, the story experience dissolved as soon as it was over. One of the reasons Toy Story 3 was so great (and all of Pixar’s movies – which put a heavy emphasis on theme) was that it kept harping on the theme of “moving on.” That there are phases in your life where you have to move forward, even if you don’t want to. In Liar Liar the theme was obviously “truth” and the consequences of not telling it. Even in the seemingly depth-less Dumb and Dumber, the theme is “taking a chance.” Refusing to be held back by the rules and restrictions of society. There’s an opportunity in The Assassination of George Lucas to write a movie about people who are afraid to grow up. Had that been explored here, this script would’ve lingered in the reader’s mind, instead of disappearing into space like the opening crawl.