Genre: Horror

Premise: (from IMDB) Set in a medieval village that is haunted by a werewolf, a young girl falls for an orphaned woodcutter, much to her family’s displeasure.

About: David Leslie Johnson’s script “Orphan,” made a lot of noise when it was picked up a couple of years ago. Even though it didn’t make a huge dent in the box office, I thought it was pretty good, especially the bizarre twist ending which I wouldn’t have predicted had you given me a hundred tries. Johnson has a very enviable backstory. He was lucky enough to have been mentored by Frank Darabont (working with him on both The Green Mile and Shawshank). The Girl With The Red Riding Hood stars Amanda Seyfried, Gary Oldman, Virginia Madsen, Shiloh Somebody and Julie Christie. Catherine Hardwicke, the director of the first Twilight film, is directing.

Writer: David Leslie Johnson

Details: 120 pages – revised first draft – April 16, 2009 (This is an early draft of the script. The situations, characters, and plot may change significantly by the time of the film’s release. This is not a definitive statement about the project, but rather an analysis of this unique draft as it pertains to the craft of screenwriting).

You say I don’t do horror. A pox upon you! I do horror. I’m doing horror right now knuckleheads. I heeded all your nasty e-mails and death threats and am finally giving you want you want. Okay, none of that is true. I’m only reviewing this because I hated the other script I was going to review (“36”) and couldn’t muster up the energy to review it.

But here’s the truth. I WOULD review more horror IF there was more horror to review. It seems like every horror script that comes down the pipeline is either a shitty remake or a sure-to-tarnish-the-original sequel. All I’m asking for is ORIGINAL HORROR. Something fresh and unique, like Johnson’s previous effort, Orphan. Any spec sales that fall under that category, let me know, cause I’ll be happy to read them.

So, The Girl With The Red Riding Hood is a “gothic” reimagining of that famous fairy tale, “Little Red Riding Hood.” Johnson has been saddled with the difficult task of fleshing out this 5 minute story into 2 hours. The results are, I suppose, solid, but since this isn’t really my thing, I had a hard time getting into it.

It’s 1324 in a French village and 17 year old Isabelle is having a secret romance with fellow villager, and brooding hunk, Peter, who works for her father. However, Isabelle is told that she’s being married off to a man named Henri to settle a debt between her and Henri’s family. Don’t you just love the old days? Have a problem with me? Here, take my daughter.

Isabelle is devastated but she and the rest of the village have bigger issues to battle. A rogue wolf has been terrorizing the town for decades and while it hasn’t killed any of them recently, signs point to that changing soon. Wolf be hungry. So scared are the villagers that they send for a “Witchfinder General” by the name of Solomon. I’m, of course, wondering the same thing you are. Why would you hire a witchfinder to find a wolf? (see how bad I am at reviewing horror?)

Well Solomon, a very serious individual, is too busy being pissed off to care what I wonder. He explains that this isn’t a wolf terrorizing their town. It’s a WEREWOLF. Solomon knows all about werewolves, you see. He’s killed one before. A werewolf that ended up being his own wife! By the name of Bella! Okay, I’m kidding I’m kidding. She wasn’t named Bella.

Anyway, Solomon and his men lure the werewolf into town, where it becomes preoccupied with Isabelle, and after finally getting her alone, it TALKS. Yes, this werewolf can talk. It wants Isabelle to come off with him. Apparently it’s not a very smart werewolf or it would know that people don’t run off with werewolves! Unless of course, the father orders them to. Then it’s okay.

Afterwards, Solomon realizes that the werewolf is not some rogue wolf at all, but that it lives here, in the village. Someone, one of them, is the wolf! The town naturally starts freaking out, and the mystery is on. Which one of them is the wolf?? And will it kill them all?

Okay so, disclaimer time. This isn’t my thing. Doesn’t matter if this were Oscar-worthy writing, I probably wouldn’t like it. Having said that, it’s a solidly executed script. I admit that the one area of writing that intimidates me the most is swords & shields period pieces. Anybody who can write dialogue for a time they did not exist in, where people spoke in a rhythm and a vocabulary as familiar to us as Japanese, I have a lot of respect for. And I think Johnson did a nice job with that.

I also thought he did a good job keeping the story fresh. There’s little twists and revelations here that throw the story in another direction just when it needs it. We have a devastating family secret that’s revealed about Isabelle’s sister. We have Solomon showing up to add some ass-kicking to the mix. We have a wolf who’s able to speak. All of that really kept you on your toes.

But if there’s one type of story I don’t respond to it’s the “Let’s wait here and die,” story. When you throw a bunch of characters into a location and they just wait for the bad guys to show up – that’s no fun for me. It’s not that you can’t make it work. I just like when my characters are active, when they have plans. In Aliens, they’re not just waiting for the aliens to kill them. They’re formulating a plan to get the hell out of there. Johnson’s able to infuse the characters with some proactive moments, but in the end, they’re still just a bunch of people waiting around.

This reminds me. Didn’t the original Red Riding Hood walk through a forest? Wasn’t that the big set piece of the story (did they have set pieces back in the fairy tale days)? That she was going somewhere and the wolf cut her off? I guess I kept waiting for this long journey she would have to take through the woods, knowing that the wolf was out there, and the ensuing suspense that would come from whether she would make it or not. Not a huge deal but it seemed like that kind of scene could have some potential and it was a part of the original story so I was confused as to why it wasn’t there.

Despite this not being my cup of tea, I can see it working. The image of an innocent girl in a red riding hood is so iconic that I can’t imagine the trailer not being cool. The question is, does the public’s demand to have their werewolves with ripped abs and predetermined teams make a tale like this obsolete? We’ll have to wait and see.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Hollywood likes things they know. They like to get behind stories the public’s heard of before because then they don’t have to spend a billion dollars educating them on it. You and I have heard of Red Riding hood, so there’s a familiarity factor there. There’s no familiarity factor with “Blue-shoed Thomas” or “The Old Man With The Green Jacket.” For that reason, fairy tales are a great place to look for stories. Nobody owns the rights to them, and many are well-known. The trick is to throw a unique twist on the tale to make it fresh. Remember how cool that video game “Alice” was? They simply threw Alice in Wonderland into the horror genre. What about taking the Three Little Pigs and turning it into a modern day comedy starring Jack Black, Jonah Hill, and Phillip Seymour Hoffman? I’m only half-joking! But seriously, if you can find a cool spin on one of these tales, run with it. I see a lot of new writers get noticed this way.

Remember guys, time is running out to enter The Champion Screenplay Competition. July 30th is the final day they’re accepting submissions. Head over to the site ASAP and sign up, and if you want to find out more about the contest head, Jim Mercurio, read the interview I did with him here. Nicholl Smicholl. It’s Champion time!

Genre: Comedy

Premise: (from IMDB) A father’s life unravels while he deals with a marital crisis and tries to manage his relationship with his children.

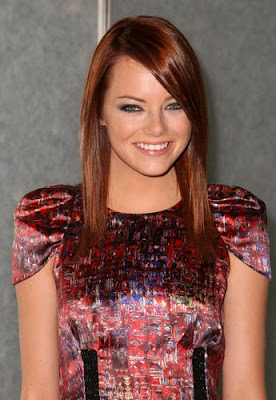

About: Helping keep that big spec sale dream alive, Fogelman’s comedy sold for a 2010 best 2 million dollars! What is this? The nineties?? Fogelman’s name may sound familiar as I just reviewed his Black List script, “My Mother’s Curse,” last week. The film stars Steve Carell (who was attached for the sale), Ryan Gosling, Kevin Bacon, Emma Stone, Marisa Tomei, and Julianne Moore. So live it up people, cause we don’t see these big sellers too often.

Writer: Dan Fogelman

Details: 121 pages – Feb 19, 2010 draft (This is an early draft of the script. The situations, characters, and plot may change significantly by the time of the film’s release. This is not a definitive statement about the project, but rather an analysis of this unique draft as it pertains to the craft of screenwriting).

I have a lot of good things to say about this script. Plot, character, and execution come together in this tale like a concoction of Coldstone’s ice cream. And while I know some of you will pan it for its feathery light subject matter, make no mistake, there is some serious skill on display here. In fact, I’d go so far as to say this is the best executed comedy I’ve read since The F Word.

But before we get into it, let’s acknowledge the rhinoceros in the room. If you or I had written this script, there’s no way anyone would’ve read it. The premise is too simple: A man is thrust back into the single life after his wife asks for a divorce. That ain’t going to win Pitch Fest at the Expo, sunshine. But this is one of the realities of the business: Professional writers don’t need a flashy logline to get their stuff read. Their NAME is the flashly logline. And that’s a good thing. Cause when you sell your script, your name will be the flashy logline as well.

42 year old out-of-touch out-of-style out-of-sync Cal thinks he has the perfect life. He fell in love with his high school sweetheart, Tracy, when he was 17, and the two have been married ever since. They have two beautiful children, 13 year old Robbie and 8 year old Mollie, a wonderful house, and an unlimited supply of happiness.

Or at least, that’s Cal’s view of things. It’s been a while since he’s seen things through his wife’s eyes, and that’s going to cost poor Cal in the form of a blindside. Usually, you have a ‘feeling’ when the old relationship is about to implode. But Cal is clueless when his wife breaks it to him that she’s been having an affair with David Jacobowitz and that she wants a divorce.

After getting over that shocker, Cal’s inadvertently thrown into the world of dating. Now for anyone who’s been off the market for a significant period of time and then come back, you’ll recall that dating changes QUICKLY. Five years ago is nothing like today. And five years before that was nothing like five years later. But here’s the thing with Cal. HE’S NEVER DATED. EVER. Tracy was his first and only. This is a world completely alien to him.

Jacob Palmer doesn’t date either. But that’s because he’s perfected a pick-up technique that requires less than a minute of conversation. Palmer can get you from A (the bar) to Z (his place) in less time than it takes most guys to order a drink. The problem with Jacob is that that’s all he does. He sits at a bar booth every night with his perfect hair, his perfect scent, and his perfect outfit and just picks up woman after woman. He doesn’t know the meaning of love.

It just so happens that Cal starts hanging out at Jacob’s bar every night and tells anyone who will listen his sad sack story about asshole David Jacobowitz fucking his wife. Jacob is horrified by this man he deems to be one step above mentally retarded. Just so he doesn’t have to witness this pathetic display anymore, Jacob offers to teach Cal how to pick up women.

Cal’s not even sure he wants to pick up women but anything that takes his mind off David Jacobowitz’s naked body is a good thing, so he agrees. Jacob gets Cal a new haircut, new clothes, and a new attitude, and after a few conversation-related tips (namely: “don’t talk. Ever.”), Cal starts picking up women left and right.

Now at this point you’re probably saying, “What so great about that? It sounds pretty boring.” And I’ll admit, the first half of this screenplay is pretty average. But where Crazy, Stupid, Love excels is in its second half, where all the characters and the intricate relationships that have been built up between them start smashing into each other like pinballs.

See what we realize, is that the first 60 pages were all one big setup, and the last sixty pages are a continuous ESPN ticker feed of payoffs. Tracy is being stalked by the man she had an affair with. Cal realizes all these one-night stands are meaningless and tries to get Tracy back. Cal and Tracy’s babysitter, Jessica, is in love with Cal. Cal’s son Robbie, is in love with Jessica. Just when it looks like Cal and Tracy are going to get back together, she learns that one of his conquests was Mrs. Thompson, Robbie’s teacher! Cal and Jacob end up becoming best friends. But then Jacob ends up falling in love with a girl, who ends up being the worst possible girl he could fall in love with. Even little Mollie is in love, with Zac Efron and High School Musical. And the further all these relationships go, the more “crazy,” the more “stupid” they get.

Blake Snyder said in his book “Save The Cat!” that there needs to be one scene in every screenplay that a producer can point to and say “That’s a movie.” In “Stop Or My Mom Will Shoot,” Snyder’s one produced credit, he said that that scene was a chase scene where, instead of two cars screaming through the streets of downtown, Stallone’s mom is driving 10 miles an hour, pulling up short at stop signs, and holding Stallone back with her arm whenever they came to a stop. That, the producer said, is what convinced me this was a movie.

Here, not only do we get that scene, but we get the reason why this script sold for 2 million dollars. It’s the climax of the story, a huge sequence where all of these relationships finally collide with one another in this glorious wacky explosion. It’s executed so perfectly and with such skill that for a brief moment, you sit up and think, “This is what screenwriting is all about.” And it really is. It’s that moment where all of the variables in your story come together in that perfect harmonic climax. It’s really good stuff.

This script also supports my belief that every character should have something going on. They shouldn’t just be an ear for the main character to disclose information to (like so many amateur scripts I read). Cal’s trying to get his wife back. Jacob’s trying to get laid. Bobbie’s trying to get Jessica. Jessica’s trying to get Cal. David’s trying to get Tracy. Even Molly, the daughter, is obsessed with High School Musical. Nobody’s left out to dry here, so we’re never bored, even though we’re jumping around to a lot of different stories.

And finally, this script does what so many comedy scripts fail to do – it packs the story with heart! And I think heart leads to big bucks. I really do. When you make a reader FEEL something at the end of a screenplay, it stays with them. It makes them want to recommend it to others. All comedies should have some heart dammit! This is proof-positive why.

Really really dug this script. Only didn’t make the Top 25 because the first half was a little predictable. Oh and hey, is this not the single most perfect role for Steve Carell that could’ve been written??

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: I don’t think you should write a low-concept comedy if you don’t have some connections in the industry. Had an amateur writer tried to get reads from this, they probably would’ve been ignored, as the premise is too generic. As an unknown, you need more flash in your pitch to get noticed, so I’d stick to higher-concept fare if you can.

Genre: Thriller/Drama

Premise: (from IMDB) Based on a true story, a mountain climber becomes trapped under a boulder while canyoneering alone and resorts to desperate measures in order to survive.

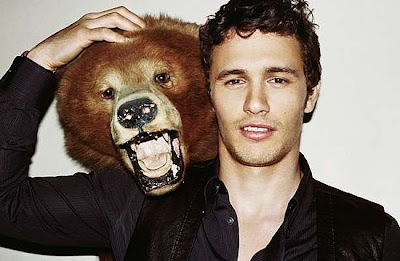

About: The buzz hit early on this script, highlighted by the fact that there will be an entire hour without a shred of dialogue. One of the best directors in the business, Danny Boyle, just finished the film. The script is written by his Slumdog Millionaire collaborator, Simon Beaufoy. James Franco plays the lead role. You can learn more about the real-life story here: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aron_Ralston.

Writer: Simon Beaufoy.

Details: 83 pages – April 1, 2010 draft (This is an early draft of the script. The situations, characters, and plot may change significantly by the time of the film’s release. This is not a definitive statement about the project, but rather an analysis of this unique draft as it pertains to the craft of screenwriting).

A question I hear a lot is, “Have you ever read a bad script that became a good movie?” The answer is no, I have not. But the ones that come closest are usually from directors like PT Anderson, Malick, Nolan, Mann, and Sofia Coppola. These helmers have such a powerful and unique style that the story almost becomes secondary to the filmmaking. For example, one thing I loved about Inception was the score. That deep trombone like bass that cycles throughout the film unnerved me in a way a story turn or a character revelation could never do. These kind of filmmaking-specific nuances will never substitute for a good story, but sometimes they can come pretty close.

127 Hours may very well be one of those films, because as a script, I didn’t think it was very good. It isn’t bad. It’s just…predictable.

For those cinephiles who saw “Into The Wild,” a few years ago, Sean Penn’s directorial effort about a man who sells everything he owns and heads for Alaska, Aron Ralston is very much like the character in that film, Christopher McCandless. He’s an adventurer, an outdoor enthusiast, a lover of nature. And like McCandless, he does everything exclusively by himself.

This is exactly how we meet Aaron, heading down to Blue John Canyon on his bike – alone. Once he reaches the desert, he locks up and sprints towards the canyon.

There he runs into a couple of girls, Kristi and Megan, who feel a bit like filler. The problem with writing a script with only one character is that you only have one character to develop. In other words, you don’t need a lot of space. But in order to get the page count up to feature length, you have to put something there, and I’m guessing that’s why these two are in the script (from what I understand, Aron *did* meet them in real life).

So the girls appear, have a few conversations with Aron telling us what we already know, that Aron rides life solo, then scram. But not before telling him about a party they’re going to 20-some miles down the road. You can’t miss it, they say. There’ll be a gigantic Scooby-Doo balloon swaying in the wind.

Later, he makes his way to a canyon/cliff area, starts running around and exploring, accidentally dislodges a boulder, gets chased Indiana Jones style, squeezes out of the way at the last second, but is unable to get his arm out of the way in time. The boulder catches it against the rock. Aron is shocked when he realizes…he’s stuck.

Thus begins Aron Ralston’s 127 hours of hell.

127 Hours uses three devices to keep us entertained – Video diaries which Aaron leaves on his video camera, flashbacks to his old girlfriend, and a series of hallucinations. Interspersed throughout these moments are Aron trying to figure out what to do. I don’t think I’m spoiling anything here since this is a real-life story, but eventually Aron realizes that the only way he’s going to survive is if he cuts his arm off – a process made difficult by the fact that he only has a Swiss army knife. And not even the real thing either. A cheap Chinese knockoff.

Essentially 127 Hours is a character piece about a man who realizes what being alone is really about. There’s a difference between the kind of alone where you get to pick and choose when you hear others’ voices, and the kind of alone where you don’t hear any voice but your own. As days dissolve into one another, Aron comes face to face with this reality, and begins to appreciate and understand how desperately all the people in his life have tried to connect with him.

This raises a bigger question: If Aron somehow gets out of here, will he finally look to bring these people into his life?

But if I’m being honest, it was hard to root for Aron. This might seem like an odd declaration, but I don’t have sympathy for people who do stupid shit. You read in the paper, “A freeclimber falls 3000 feet to his death.” You know the first thing that comes to mind when I hear that? “You probably shouldn’t have been climbing 3000 feet in the air WITHOUT ANYTHING TO SUPPORT YOU!” I mean if I ever start juggling chainsaws in Vegas and accidentally cut myself in half, I fully expect anybody reading an account of my ordeal to reply: “Serves you right moron.” I mean Aron isn’t cliff-diving into lava here, but running around the desert and climbing mountains with no one else around and without telling anybody where you are is a pretty stupid thing to do. So I just wasn’t onboard with him from the get-go.

I was also never surprised by this screenplay. As soon as Aron got stuck I thought, “There’s three things he can do here: talk to the video camera, go into flashbacks, and hallucinate.” Sure enough, that’s exactly what happens. And while I somewhat enjoyed Aron exploring his connection issues via flashbacks and hallucinations, in the end these scenes were too repetitive to fully keep me interested. At a certain point I was like, “Let’s cut off the arm already.”

Another unfortunate aspect of this story is that we know the ending before the film starts, draining the script of a good portion of its suspense.

Despite all this, I still think 127 Hours can be a good movie. Boyle is a filmmaker that plays in the same sandbox as Nolan, Mann, and Malick, so he obviously saw something worth getting dirty for. If I had to bet, I’d say he was drawn to the hallucinations, which become a huge part of the second half of the film. Visually, these are extremely weird and powerful (I imagine the huge floating Scooby-Doo balloon in the middle of the desert will be the “what the fuck” trailer image that sells a good share of tickets) and if there was ever an opportunity to explore the limits of your imagination, no-holds-barred hallucinations would be a great start.

But if it will be enough to make up for a rather ordinary story, I don’t know.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: One of the reasons we go to the movies is to see characters try and overcome the same issues we’re trying to overcome in our own lives. The exploration and eventual conquering of these “flaws,” when done right, can be the most powerful part of your story, because it gives us hope that we can conquer our own issues. There are a few character flaws that consistently work well, and one of them is the one Beaufoy uses here – Aron’s refusal to connect with the world. I don’t know what it is, but when we see someone who refuses to connect with others, we instinctively want them want them to connect with others. I’m reading The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo (the book, not the script) and Lisbeth Salander has this exact same flaw. She’s so disconnected from everyone and everything that we pine for her eventual transformation. We want her to initiate a hug, trust someone, open up to a friend. And the further she pulls away, the more desperately we want to pull her in.

Genre: Drama

Premise: A selfish workaholic chef tries to get back into the restaurant game after a much publicized meltdown years ago.

About: Like a lot of projects that gain instant notoriety in Hollywood, Untitled Chef Project burst onto the scene after David Fincher attached himself to it. This would have paired him with thespian Keanu Reeves had it happened, but the project fell apart for reasons unknown. I’ll tell you one thing, these damn “Untitled” monikers sure do suck the life out of a script. Who gets excited for a project with “Untitled” on the front page? Anyway, the script made the 2007 Black List, and in a case of complete coincidence, had the exact same number of votes – three – as Jeff The Immortal. Hmm, could the low end of the 2007 Black List contain a secret stash of amazing unknown screenplays? — You may also know Knight as the writer of one of last year’s highly rated Black List scripts, the Bobby Fischer bio, Pawn Sacrifice (which you may remember I didn’t like very much).

Writer: Steven Knight

Details: 116 pages – July 25th, 2007 draft (This is an early draft of the script. The situations, characters, and plot may change significantly by the time of the film’s release. This is not a definitive statement about the project, but rather an analysis of this unique draft as it pertains to the craft of screenwriting).

I am going to admit something that I don’t admit to many. I love Gordon Ramsey. And I love Kitchen Nightmares. I love watching Gordon Ramsey tell a chef that their food is awful. I love when he goes into a kitchen, turns over a box and finds roaches. I love when he discovers mold on a tomato, stuffs it in a cook’s face, and tells him serving that tomato is the same as pointing a gun at a customer’s head and pulling the trigger. And I love how every time, after his assessment of the restaurant, even though it’s all so clearly planned, he says there’s nothing he can do to help them and walks away. I love how we stay on the owners, who are deciding whether they should go after him or not, even though Gordon Ramsey is always exactly 500 feet away, standing on a mark determined hours ago so that he’s in the best possible light when the camera arrives. And I love how even though there’s still 45 minutes left in the show, I’m still sitting there wondering, “What if he doesn’t come back? What if he doesn’t help them?? Will the episode just….end????” If you are not a Kitchen Nightmares fan, I implore you to seek out the one where Gordon Ramsey goes into an Indian restaurant in New York. You will become a convert.

Ironically, this is exactly why I DIDN’T want to read Untitled Chef Project. I was afraid it was a script meant to capitalize on the whole Chef reality TV craze. And as far as inspiration goes, basing a movie on a reality show is one step below basing a movie on a board game.

But if there’s one thing Fincher has proved, it’s that he gets his grubby paws on the best material in Hollywood. By far, this man finds the coolest books, scripts, articles, and bios to develop. No one else even comes close. This is the only thing that gave me hope that Untitled Chef Project would be good.

Adam is an amazing chef. People wait months to eat his food, he has one of the best restaurants in Paris, and he has two Michelin stars to his name (getting a Michelin star is akin to winning three World Series in a row and being the MVP in each one). Adam has a problem though. HE’S FUCKING INSANE! The guy snorts coke while he’s preparing tuna tar-tar and would probably do heroin as well if it weren’t so logistically demanding. Not only is Adam a lunatic, he’s insanely dangerous. He’s violent, self-destructive, and maybe even suicidal. When we meet him, all of this has finally caught up with him. Adam self-destructs, losing his restaurant and losing everything else in his life.

Cut to a few years later and Adam has picked himself back up. He lives in London and he’s been getting that urge to start a new restaurant, which means finding a team. For those of you who saw Inception, this is like the first half of that movie but without all the exposition. It’s time to find out who’s going to go to war with him.

The key to every team, and particularly every chef, is a great sous chef (the right hand man).

So Adam sets up an interview with his top prospect, the talented, beautiful, and guarded Sweeney. But Adam doesn’t have any money for an office yet. So where does he interview Sweeney? Why McDonald’s of course. And this was the first moment I realized that Untitled Chef Project was different. Well, when Adam was ingesting lines, fighting off drug dealers and preparing a meal at the same time, I knew the script was different then. But when the best chef in the world starts philosophizing about how great McDonald’s is, you know you’re in for something fun.

Anyway, Sweeney knows about Adam’s shady history, but can’t pass up the opportunity to learn from someone of his stature, so she says yes. Adam completes his rag-tag group of culinary-geniuses, talks someone into giving him a million dollars, and opens his restaurant in the middle of London.

You’d think with someone as genius as Adam, building a great restaurant would be easy. But Adam is…different. Not even perfection is perfect enough for him. This is a man who refuses to allow even a single mistake. Michelin stars are only awarded to those dining experiences which are perfect. Not a single thing can be out of place: not the service, not the food, not the atmosphere, not even the damn silverware. And because Adam is trying to achieve something that no other chef has done – get a third Michelin star – he demands of his workers that they be Gods. Every. Single. Day.

As if to show just how serious he is, one of the early nights has a couple of screw-ups. Adam gathers everyone in the kitchen and proceeds to lose his shit in a way that would make Bob Knight say, “Whoa, you went too far there dude.” Adam becomes so angry in fact, that he actually holds a knife to Sweeney’s throat. And you really believe that in that moment, he’s thinking about killing her. You believe he’s actually considering it. Let me give you some perspective here. THIS IS THE FEMALE LOVE INTEREST! You have your protagonist about to KILL the female lead in your movie!!!

As the script hits the second half, it begins to focus more on this love story. But fear not all you readers who hold Sandra Bullock and Matthew McConaughey DVD burning parties. This is not romance of the pillow talk variety. Knight wisely keeps these two separated for as long as possible, so that the tension and conflict are maximized. We’re wondering if Sweeney can see this man as anything but the crazy lunatic he is. We’re wondering if Adam can find enough of his heart to let another human being in. It does not read cheesy. It does not feel saccharine. It’s harsh and it’s real and it’s pitch-perfect.

This is a character piece that explores one of the most interesting characters I’ve seen all year. It’s about a man obsessed with himself and obsessed with his work. He’s unable to enjoy life, unable to enjoy the people around him, and he takes that out on anyone who steps in his path. There is a great emotional scene near the end of the script where Sweeney asks Adam for a day off to celebrate her daughter’s birthday, and his answer and the subsequent scene afterwards hit you in a way that scripts just aren’t supposed to do. You’re supposed to need the sweeping music and the perfect cinematography and the actor’s faces for this shit to work. Here, it works right on the page.

There is WAY more to this than I’m letting on. But it would take me too long to get into it all. Likewise, it would take me forever to discuss all the great scenes here. There’s a hilarious scene where Adam adds marijuana to a dish to influence a local food critic. There’s his insistence that, after a bad night, they give away free food for a week, something he knows very well could bankrupt the eatery. There’s a wonderful date scene where Adam and Sweeney finally go out, but with so much sub-text going on that it becomes one of the best “first date” scenes I’ve ever read.

But I think probably the coolest thing about this script is that the lead character is both the hero and the villain. He’s Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. And it’s such a great reminder that if you want to get your script noticed, write a part that an A-list actor would love to play. Go read this script right now and tell me if you were a movie star, you wouldn’t want to play this role. I dare you.

And you know what’s nuts? You know who the perfect actor would be to play this part? The one who would heads and tails kill it? Mel Fucking Gibson. I’m not kidding either. He would be perfect for this role. But the guy had to go TNT on his career last week and I don’t think we’re ever going to see him again as a result. It’s probably deserved but if this guy ever wants to jump back into acting , this better be the first script he looks at.

Anyway, this script is fucking awesome, and it’s not just going in my Top 25. It’s going in my Top 10.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: In Untitled Chef Project, Adam has a rival who owns a competing restaurant. Naturally, he’s trying to take Adam’s restaurant down. So Adam’s manager wants Adam to go there and check the restaurant out – see if there’s anything they’re doing better there than they’re doing here. But he knows Adam’s rage will get the better of him so he suggests that Adam take someone with to prevent him from beating the shit out of the other owner. Well Adam doesn’t know anybody. He’s too wrapped up in work to have friends. This leaves him with only one option: Sweeney. Now, after 80 pages of this sexual tension building up between the two, they’re finally going out on a date. But they’re not REALLY going out on a date. No, this “outing” is all under the pretense of business. So Sweeney can’t really say no. Now since Adam knows his rival is a slimy piece of shit, he can’t let him know that Sweeney is his sous chef, since he knows he’d try and steal her. So he suggests that the only way they can do this is if Sweeney pretends to be his girlfriend.

Now the reason I went into such extensive detail about this is because THIS is how you build a great date scene! You create a series of situations that work against the date. By doing so, you add mounds of conflict and subtext, which makes the date way more interesting than it ever would’ve been had it just been two people going out. When I read amateur scripts, the date scenes are always boring because they don’t have ANYTHING ELSE GOING ON. Look at how much is going on here. Adam didn’t want to take Sweeney in the first place. Sweeney is excited to be here but knows she shouldn’t be. The two have to act like they’re together, even though they’re not. Adam has to concentrate on what his competitor is doing, so he can make his restaurant better. Adam doesn’t want to ruin the work relationship he has with Sweeney, and is trying to keep this professional. Do you know how easy it would be to write dialogue for this scene? There’s so many things going on to draw from.

Now I’m not saying that every date scene has to be this complicated. Complications will vary depending on when in the story the date happens and what kind of story you’re writing. But you should always look to complicate the surrounding variables of the date to make the scene more interesting. Two people just straight up talking at a table is the most boring thing you can do in a film. Look to make it interesting by adding other variables to the mix.