Been flipping through Amazon, trying to find some great deals and indeed there are a bunch. Personally, I’m hopping on Community and Princess Bride. I’ve been meaning to get The Wrestler forever. Toy Story 3 is a no-brainer. Finally saw Train Your Dragon and liked it, though not enough to purchase it. Avatar Collector’s Edition I was going back and forth on. But I’m assuming there’s some awesome “making-of” shit since it’s from the guy who can make anything out of anything, James Cameron. Black Fridayers unite! Time to shop!

Community Season 1 for 10 bucks.

The Princess Bride 20th Anniversary Edition for 4 bucks

Roger’s favorite, “Kick-Ass,” Blu-Ray/DVD combo for 10 bucks.

Reservoir Dogs 15th Anniversery Blu-Ray for 8 bucks.

Slumdog Millionaire for 4 bucks.

Office Space Flair Edition for 5 bucks.

The Wrestler for 5 bucks.

Edward Scissorhands 10th Anniversary Edition for 5 bucks.

Pre-release (Dec. 7) Inception for 17 bucks.

Where The Wild Things Are for 9 bucks.

How To Train Your Dragon Blu-Ray/DVD combo for 18 bucks.

Toy Story 3 Blu-Ray/DVD combo for 25 bucks.

Avatar Extended Collectors 3-Disc edition for 15 bucks. Blu-Ray version

for 25 bucks.

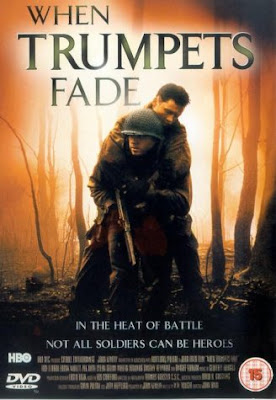

Genre: War

Premise: A private bent on saving his own ass in the forgotten Battle of Hurtgen Forest in World War 2, finds himself repeatedly promoted as those around him continue to die.

About: When Trumpets Fade was actually already made into a film back in 1998 (I believe it only played on HBO). But it has an inspiring screenwriting story behind it so it’s definitely worth a look. The script was passed to a development exec at Dreamworks named Nina Jacobson as a writing sample for a “new” writer (Vought had actually been writing screenplays for ten years – living out in Middle America, he hadn’t even met his agent, who had signed him based on this script). Already having read two terrible scripts that day, she almost gave up before giving this one a shot. She read it and loved it, so much so that she wanted to give it to Steven Spielberg, a bit of a gamble as he was already in pre-production on another World War 2 flick called “Saving Private Ryan

.” Despite that, Spielberg read the script the next morning and loved it as well. He wanted to meet the writer. Nina, imbued by this confidence, wanted to buy the script and give the writer a blind script commitment. This is her account of her call to Vought: “When we speak, Bill (Vought) seems dazed and midwestern, delighted but unsure. It’s as though he thinks this whole thing is a big snafu, an error in the lottery that will end up being noticed and rectified at any moment, so best not to celebrate and draw attention to the mistake.” A few days later Vought is on a plane to L.A. and a few hours after he lands, he’s in a room with Steven Spielberg, discussing his script. The ultimate screenwriting dream. There’s a wonderfully detailed account of the whole story on WordPlayer. When Trumpets Fade was made in 1998 and directed by John Irvin. It’s based on a true story of the Battle of Hurtgen Forest in Autumn of 1944 during World War II. A few days later, the Battle of the Bulge began, leaving the battle of Hurtgen Forest largely forgotten.

Writer: W. W. Vought

Details: 116 pages – original 1996 draft (This is an early draft of the script. The situations, characters, and plot may change significantly by the time the film is released. This is not a definitive statement about the project, but rather an analysis of this unique draft as it pertains to the craft of screenwriting).

One of the cool things about Steven Spielberg and what’s allowed him to be on top of the movie business for so long, while so many others have faded into obscurity, is how much emphasis he puts on finding new writing talent. Spielberg realized a long time ago that writers are the lifeblood of the industry. Without their ideas, without their unique voices, without their stories, you have nothing.

And to you or I, who know what it’s like to stare at a screen for 10 hours a day, that may seem obvious. But there are so many other producers in this business who believe in shortcuts, who believe that all you need is an idea, the latest writer gun-for-hire, and a really good D.P., and you can slap together a 200 million dollar hit in six months. If you want to know why none of these guys have Spielberg staying power, look no further than that mentality.

I’m not sure how Spielberg’s operation works, but from what I can tell, he puts the same amount of effort into finding new writers as Apple puts into R&D. In other words, a whole lot. I can only imagine how much rough they have to trudge through to find those diamonds, but they eventually find them. And as long as they keep finding them, Spielberg will continue to stay on top.

So what was this script that got Spielberg and Nina so excited? Was it really that good?

Let’s find out.

Private Manning cares about one guy and one guy only. Numero Uno. Even in the heartpounding opening scene, as he carries a dying soldier to safety, the implication is that the only reason he’s alive and everyone else in his platoon except for this guy is dead is because he stayed back, hid out, stayed out of the fray in order to keep his own heart pounding. When he gets back, his superiors tell him as much. They call him a coward. A survivor only through fear.

Not that he doesn’t deserve to be scared. The Americans are located in an area known as the “Death Factory,” a forest so thick with Germans they might as well grow there. And they are massacring the Americans group by bloody group. With all the leaders dying, drastic measures must be taken. So Manning, who was hoping to go home, is instead promoted. The king of the chickens is now in charge of his own batch of chickens.

His platoon shows up a day later, a group of fresh-faced scared kids who have no idea what’s in store for them. The noobs are thrown into battle right away by Manning. And within minutes they’re getting shot at with real bullets, they’re being hunted by real Germans, they realize they could really die. And there’s nothing they can do about it.

After a few minor missions, Manning gets the news he’s been waiting for. If they can take out a few huge artillery guns that the Germans have perched up on the hills, Manning will get his wish to be sent home. So the normally passive Manning puts his game face on, and sets out to do what thousands of other men have been slaughtered trying to do.

When Trumpets Fade has some genius in it. Right off the bat you’re pulled in by Manning’s desperate attempt to keep this other soldier alive. We know the man’s going to die. He knows he’s going to die. But Manning tries his best to keep him calm, to keep him going. It’s not only an exciting way to open a script (make those first ten pages great!), but it makes us immediately like our hero – whose selfishness would otherwise make him hard to warm up to. I mean this is a really intense scene and even though we’ve seen it a hundred times before, there’s something real and authentic about their exchange. We don’t even know these people and yet we’re hoping against all hope that this guy makes it. After this scene, I was willing to go anywhere Manning took me.

Also, just like any good movie setup, you want there to be some irony in your story. In this case we have a guy who doesn’t want to lead who’s forced to lead. That right there is a compelling character whose very existence for the rest of the film is steeped in conflict. Conflict = drama. And drama is what keeps your audience’s interest.

The strange thing about When Trumpets Fade is that no real story emerges until after the midpoint (when Manning is given orders to take out the artillery guns). Up until that point, our characters are repeatedly sent out on minor missions that don’t really have anything at stake. This would normally result in a bunch of boring scenes. But there’s something honest and authentic about these missions that keeps us reading.

Even though we get all the cliché war moments where you look to your right and the guy you bunked with last night now has half his face blown off, the dialogue feels real, the missions intense, and our desire to see how Manning reacts to it all, if he’ll learn, keeps us engaged. To simplify it, even though I’ve seen dozens of war movies, this script made me feel like I was in the war.

But there are still a lot of mistakes that are made , and raw ones at that. I guess we’ll start with Manning, whose flaw, while interesting, was at times unclear. Manning is selfish AND a coward. Last time I checked those are two completely different things, and while that may work fine in real life, it’s confusing when a main character has two separate fatal flaws he’s battling. We’re not sure which one to identify him with, which alters our interpretation of the story. In other words, the script reads much differently if we’re assuming Manning is a coward as opposed to if we’re assuming Manning is selfish.

I thought the supporting characters could’ve been better constructed as well. Warren, who plays the second lead in the movie, is someone I know absolutely nothing about other than that he’s fresh-faced and wears glasses. There were 5-6 other guys whose backstories were even thinner. This was a big deal since whenever the group faced a dangerous encounter, the only character I cared about surviving was Manning. I cared more about that opening dying character than I did any of these guys.

The ending also needed work. Not only is there a manufactured plot twist where the other soldiers want to murder Manning (which doesn’t work at all) but the main story goal comes in so late, it’s hard to get into (I’m referring to the mission to take out the guns on the hill). Late-arriving story goals never have the same stakes attached to them as something that’s been set up throughout the story. I had the same problem with Saving Private Ryan. Once they found Private Ryan, they tried to tack on this supposedly big bridge finale. But the goal of securing the bridge came so late that we never really bought into its importance, and therefore didn’t care if they succeeded or not.

Despite these problems, the Manning character and the feeling of really being in this war won me over. I know that just a couple of weeks ago I harped on the staleness of World War 2 movies, but I have to remind myself that when something is written well, it doesn’t matter what the subject matter is. It’s going to work.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Stakes stakes stakes people. I know we can’t shut up about them here but writers are still making the same mi-stakes so we’re going to keep bringing them up. The success of your climax is directly related to how big the stakes are. The later you set those stakes up, the smaller they’re going to seem. Imagine Rocky if we followed Rocky around Philadelphia for 90 minutes. He falls in love with Adrian, helps Paulie battle alcoholism, collects money for thugs. Then, on page 90, Apollo Creed comes to Rocky and says, “I want to fight you for the Heavyweight Championship of the world.” Do you think that fight would have half the impact it has now? Of course not. What makes it so big is that every scene leading up to it addresses how important that fight is.

Slash Film has alerted me to some sweet Pre Black Friday deals.

The Criterion Collection version of the greatest movie about high school ever told, Dazed and Confused for under 10 bucks. I’m buying this one right now.

Time Bandits (who doesn’t love Time Bandits!??) on Blu-Ray for 6 bucks.

Fight Club on Blu-Ray for 10 bucks. One of the most imperfect masterpieces ever created.

Terminator on Blu-Ray for 8 bucks. I haven’t seen this in over five years. Must rewatch now!

And The Hangover on Blu-Ray for 10 bucks. A great comedy, yet its quality is often debated for some reason.

Genre: Action-Adventure/Romance/Comedy

Premise: When the infamous womanizer Don Juan starts to fall for a woman for the first time in his life, he must decide if that love is worth giving up his woman-chasing ways.

About: Don Juan won the Scriptapalooza contest back in 2004. Not the actual Don Juan, but the writer who wrote Don Juan, Patrick Andrew O’Connor. Believe it or not, this is the second script O’Connor ever wrote, which is a rare feat, winning a major screenwriting competition off your second script. O’Connor got his first produced credit last year with the indie flick “The Break-Up Artist” which he sold at the Cannes Film Festival. O’Connor recently optioned another script (whose title I can’t find) which is why people are going back and giving this script another look.

Writer: Patrick Andrew O’Connor

Details: 105 pages – undated (This is an early draft of the script. The situations, characters, and plot may change significantly by the time the film is released. This is not a definitive statement about the project, but rather an analysis of this unique draft as it pertains to the craft of screenwriting).

I’m not the swashbuckling type.

I always thought The Three Musketeers were lame and that Zorro

was a wussy for always wearing that mask. So to plop me down in the middle of the 19th century and force me to watch some primpy man trade clever barbs with another primpy man, slashing and dicing at each other in the 19th Century equivalent to Dancing With The Stars, it was akin to sending me through TSA at LAX for an extended pat-down.

But you guys have demanded more contest winners and since I work for you, the people, then dammit if I wasn’t going to review more contest winners.

Don Juan starts with, well, Don Juan standing at the foot of his dying mother’s bed. Before she kicks it, she tells Don Juan to make sure he finds love. Being only 12 at the time, Don Juan interpreted this to mean “find as much love as humanly possible.” And when we flash forward 15 years, that’s exactly what Don Juan’s doing, finding love, sometimes with three or four women a day.

In fact, Don Juan has a bet going with his biggest Lothario competition, Don Luis, on who can bed the most women in a single year. Since Don Juan is the ultimate lover, he wins handily, but not without some questionable record-keeping (he was supposedly with two women on the same day in two different countries – not an easy feat in 1830).

In order to clear his name, he proposes another bet. This bedding competition has left Don Luis yearning for the true love of a woman. As such he has asked the beautiful Ana for her hand in marriage. Don Juan proposes that he can bed Ana before Don Luis marries her in a couple of days. Under the tight scrutiny of an eager crowd, Don Luis accepts the challenge in order to secure his dignity (why this is considered “dignified” is something I can only assume people 180 years ago understood).

As soon as the challenge is accepted, Don Luis races home to his fiance to prepare her for the ensuing onslaught of Don Juan.

In the meantime, Don Juan runs into Ana’s best friend, the heartbreakingly beautiful Ines, who is a few days away from taking her oath as a nun. Don Juan is struck by the unbridled beauty of this woman and experiences something he’s never felt before while around a woman – feelings. The only problem is that Ana is the one woman on the planet not affected by Don Juan’s charms. Even his most time-tested methods fall flat with her.

And thus begins a most impossible conquest. Sleep with Ana before Luis marries her and get Ines to fall in love with him before she takes her vows as a nun. This isn’t going to be easy!

Along the way Don Juan is chased by Ines’ father, who happens to be the captain of the Sevilla Royal Guard, gets thrown into jail, helps his affable and hilarious servant hook up with Ines’ servant, breaks out of jail, and struggles to achieve these two impossible goals before the sun rises.

As you can probably tell from my exuberant review, I enjoyed this a lot more than I thought I would. One thing I worried about right away was that this was yet another standard treatment of a character we’ve seen dozens of times before. In fact, Heath Ledger just played the kindred spirit to this character, Casanova, a few years ago. The forgettable generic treatment of that character is exactly what I was expecting with Don Juan.

Usually, the writers who rise up out of that giant amateur screenwriting stew are writers who take characters like this and find a fresh take on them. That’s why Baz Luhrman’s Romeo & Juliet worked, as he transported it to modern day Los Angeles. That’s why Steve Martin’s “Roxanne” worked, as they took Cyrano de Bergerac and found a present-day angle. Here, we stay with the same character in the same setting in the same time period as we’ve always seen Don Juan. So how interesting could it be?

Very.

And there’s a reason for that. O’Connor nails the execution. It’s the hardest thing to do – take a story that we’ve seen before, tell it the same old fashioned way that everyone else has told it, and still make it exciting. The reason it’s so hard is because you have to do everything perfectly. And this is made even more amazing by the fact that this is only O’Connor’s second screenplay. I would like to know the rewrite situation on this script (is this the draft that won the contest or a newer draft?) because there are so many things he does right here.

First, the goals are very strong. And I love how Don Juan bucks the traditional single-goal protagonist structure and instead gives Don Juan TWO goals, making his job twice as difficult. I love the dual ticking time bombs, ensuring that our story moves at a breakneck pace. I love that Don Juan’s being chased by Ines’ father, which adds even more momentum (and ups the stakes – if he gets caught, he could end up in jail for the rest of his life…or worse!). And I love the exploration of Don Juan’s character flaw, his confusion and rejection of the emotion he’s so terrified of feeling – love. These are all very basic story-telling devices, but O’Connor puts them to use with amazing results.

I also loved Ciutti, Don Juan’s noble servant, who’s stuck doing everything Don Juan does, even though he’s one-fourth as capable. I thought the dialogue was witty and funny, not an easy feat when this genre practically expects it. And I really grew to love and understand the advantage of writing a story around this character. Don Juan is that impossible to resist rogue lead – he’s a liar and a cheater, which gives him a dark side, but he’s eternally optimistic and funny, making it hard to dislike the guy.

All in all I’d say this was a rousing success. And yes, I’m using “rousing” because it’s a word they’d use in the 19th Century. I’m that inspired by this script. I kind of stumbled onto it after attempting to read two Brit List scripts (both of which were littered with misspellings and sloppy writing – what the hell man??), and boy am I glad I did. The only reason this doesn’t get an “impressive” is because the subject matter isn’t my cup of tea, so there were parts I couldn’t get into no matter how well-written they were. But for a script that started at a “Wasn’t For Me” before I opened the first page, I’d say a double “worth the read” is impressive in itself.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: It’s important to always make it hard for your hero to achieve his goal. Anything that comes easy for him will feel like a cheat. However, I realized that sometimes, in a comedy, if you set it up properly, you can make a key plot point easy for your hero as long as it gets a big laugh. In Don Juan, there’s a guard guarding Ana’s house who’s both deaf and blind. We get some early exchanges with a worried Don Luis that the guard won’t be able to keep Don Juan out. The guard assures him that he can handle the job, and later when Don Juan sneaks past him easily in a funny scene, we accept it. Since it was properly set up and funny, we don’t feel cheated. Contrast this with a comedy script I reviewed the other week, We’re the Millers. I was really upset that in a movie about smuggling drugs into America, that our criminals don’t encounter any problems at the U.S./Mexico border. It’s not funny and the reason it’s easy was never set up, so we feel cheated.

Hey, how bout that? It’s Turkey Week! Again, for those outside the U.S., we have a holiday this Thursday where everybody thanks themselves. Or each other. Or someone. For reasons unknown to I, we need an entire day to do this thanking, so even though my own personal thanking will last a total of 25 seconds, I will be utilizing the other 23 hours, 59 minutes and 35 seconds to prepare for the chaos that is Black Friday (by the way, if you’re going to do your Christmas shopping, don’t forget to get either this or something from here for your screenwriting friends). So no review this Thursday unfortunately. But that still leaves four reviews, which include a contest winner, a sci-fi spec that made some noise, and maybe an amateur script (I haven’t figured out if I’m doing Amateur Friday this week or next). Right now, Roger brings us another Blood List script, and one of the crazier sounding ones at that, Underground.

What I learned: Dread. The anticipation that something horrible is going to happen to a character you care about. If you want to create moments that truly terrify (you are aiming for terror, not horror, which are two different things), learn how to create dread. Charlie is a smooth-talking wanna-be chef. I suppose his likeability can be argued, but I cared about him because I liked his relationship with Quinn. I was interested in their goal, which was their dream to open up their own restaurant and build a future together. Orbiting this couple was Seamus, a threat who wasn’t above serving fried human skin to a food critic. We know that Seamus was into bad, nasty stuff, that there was a monster within him lurking. We were waiting for the moment for this monster to reveal itself. Stakes are raised when we find out that Quinn is pregnant with Charlie’s child, and our minds can’t help but wonder, “Is this unborn child going to be put in danger? And not only that, but what kind of danger?” Because the writer put the elements of characters we care about in the orbit of a perverse monster, we anticipated a collision of the two worlds. That anticipation is dread, and it not only does it create unease and gets the imagination thinking unpleasant thoughts, but it keeps the reader wanting to know what happens next. You want to write good horror? Dread should be the bread and butter of your horror scripts.