TITAN WEEK 3 OF 5

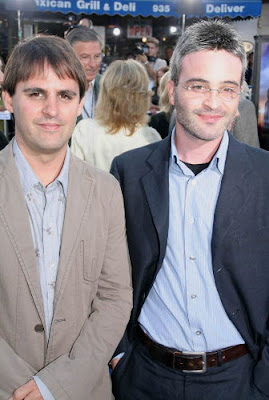

Day 1 we brought you Shane Black. Day 2 we tackled questionable titan David Benioff. And now on our third day of Titan Week, we bring in the two highest paid writers in the business, Roberto Orci and Alex Kurtzman! This oughta be fun. :)

Genre: Thriller

Premise: A widowed social worker receives a strange message that forces him to reevaluate what happened the day his wife was murdered.

About: How can you have a Titan Week without Kurtzman and Orci!! The two most beloved and respected writers in Hollywood!? Heh heh. You knew I had to pull these guys out. They’re the highest paid and most sought-after writers in town. And absolutely nobody thinks they should be but the people who hire them. Kurtzman and Orci first came on the scene in 2005, when they wrote Michael Bay’s “The Island.” They followed that with the second Zorro film, Mission Impossible 3, Transformers, Star Trek, and of course, the single greatest movie to ever be made, Transformers: Revenge Of The Fallen. But “Tell No One” is the script they wrote before all that success, all the way back in 2002. Now some of you may already be familiar with “Tell No One” as a French film that made some waves on the independent circuit in 2008 (it was released in France in 2006). I didn’t see it because I’d been burned too many times by supposedly groundbreaking French Films which turned out to be mind-numbingly horrible. I don’t think there’s anything worse than sitting through a bad French film. I’m glad I ignored it, because it allowed me to have this amazing reading experience. Now a few of you have probably noticed that the dates don’t quite match up. How can Orci and Kurtzman have adapted a 2006 film in 2002? Simple. Orci and Kurtzman have a time machine. It’s what allows them to know what we’re going to like before we like it. I’m just kidding. Or am I??? Actually, the French film was an adaptation of a novel written by American writer, Harlan Coben. I’ve never read a Harlan Coben book before, but people tell me “Tell No One” was one of his lesser efforts. Anyway, Kurtzman and Orci adapted the book before the French did. The French just beat them to the theaters. I still think this deserves the Hollywood treatment though. It’s a can’t miss baby.

Writers: Roberto Orci and Alex Kurtzman (based off the novel by Harlan Coben)

Details: 122 pages (5th Draft, 2002)

Warning: If you know nothing about this script or this movie and you like thrillers, stop now, download the script, and read it. You’ll thank me.

Uhhhhh, can someone tell me WHERE THE HELL THIS SCRIPT WAS HIDING??? What a freaking gangbusters screenplay. I haven’t flown through a story that fast since The Cat In The Hat. And I thought The Grey was a good thriller. This is the executive suite of thrillers. 3000 square feet. Sweeping views of Vegas. TVs that pop out of the floor. Tell No One? Tell everyone!

But I’ll get to that in a second. First, we gotta deal with Orci and Kurtzman.

Every burgeoning writer in town cites these two as the oozing puss-filled sores of the screenwriting world. They point to the Transformers movies as their main argument. Anybody, they say, responsible for writing those movies, cannot be a good writer. And I will say this. The Transformers movies are two of the most incomprehensible mainstream movies I’ve ever seen, especially the second one. The thing is, the fault doesn’t lie squarely with them. These guys were brought in to realize a vision from a director who has no interest or understanding of story, to plug in characters that the toy company forced them to, to come up with a believable scenario by which aliens came to earth taking the form of transforming motor vehicles, to integrate pre-existing action sequences into a story that hadn’t been written yet, and to push all of this together in a few weeks, due to the writer’s strike (on the second one). In short, they were set up to fail. Any single one of us would’ve failed as well. It’s hard enough coming up with a good script when NO ONE is telling you how to write it. But when everyone is? And in a few weeks? There’s no way.

However, I’m not here to try and convince you to like Orci and Kurtzman. I was simply curious about reading a screenplay of theirs before they hit the bigtime. These are the scripts that usually GIVE these writers a shot at the big time, so it’s interesting to see what warranted that shot. And holy shit, this shot hit the bullseye.

David Beck and Elizabeth Parker are in love. They have been ever since they were 12 years old, doing the whole “carve the initials in the tree” thing. There’s only one issue affecting their otherwise bliss-filled relationship. David has seizures. Intense full-on blackouts where he doesn’t remember a thing. And one day, not long after the two are married, David is hit by something, triggering a seizure, and he blacks out. When he wakes up, he learns that his wife has been brutally murdered – the only thing he’s ever loved, stolen from him forever.

Four years later, David, now a social worker for abused children in Philadelphia, is trying to put the pieces of his life back together. He’s even dating a doctor, Anna, who helps some of the kids he brings in. Even though it’s not what he envisioned for himself, it’s a job Elizabeth was passionate about, and he feels a duty to carry it on. But the job is taxing, difficult, and he’s thinking about moving on to something more lucrative, something that’ll give him a cozy life, something that will help him finally move on from Elizabeth.

HUGE SPOILERS – PLEASE STOP READING NOW IF YOU HAVE ANY INTEREST IN THIS SCRIPT

And then David gets a message on his computer. He clicks a link. A live video feed. Of Elizabeth. At a park. Older. Today. Right now! Looking up into the camera!

It can’t be. There’s no way. His wife is dead. Isn’t she?

As David tries to make sense of the nonsensical, a car containing two murdered men is found in the lake next to where Elizabeth was murdered. These men were killed at the same time and with the same weapon that Elizabeth was. There are grave implications to this news. The serial killer who killed Elizabeth was thought to have only killed women. That’s why he supposedly left David alive. But if two men were also killed, why was David’s life spared? David has gone from mourning widow to number one suspect.

The worst thing about that? David’s not sure he *isn’t* a suspect. And actually, he’s not sure of anything anymore. Was the video feed of Elizabeth real? A fantasy? Could his fractured seizure-ridden mind be creating this vision to cope with the fact that he killed his wife?

Forced to go on the run or end up on the wrong side of the death penalty, David must scrape together the pieces of his wife’s secretive life, and find out what really happened to her that fateful day. Old friends, old family members, co-workers – no one can be trusted, and yet he needs all of their help to survive.

Tell No One takes its cues from the best, namely The Fugitive, and actually improves on the formula. Whereas The Fugitive has two gargantuan driving forces – the chase and Ford having to find out who killed his wife, Tell No One adds two additional mysteries: Is David the killer and is his wife still alive? With all these amazing threads going on at once, there isn’t a single sub-standard moment in the script. My admiration for this screaming fast story grew by the page because I’m so used to these things falling apart under their own weight. The twists stop making sense. The character motivations become ludicrous. The finale turns out to be a letdown. But Tell No One is the opposite. Every single story decision here is perfect. In fact, if I were teaching a class on how to write a mystery thriller, this is the script I would use to teach it. It’s that good.

And why is it that good? It’s no different than what we were talking about the other day with Taken. Tell No One gets the emotional component right. In the beginning, we see David and Elizabeth grow up together, fall in love together, get married, and start their life. So when Elizabeth is killed, it’s not just David who’s lost someone. It’s us. We watched this girl grow up. We watched her love. We watched her dream. We loved Elizabeth just as much as he did, and as a result, when she returns, we’re just as desperate for David to find her as he is. But the point is, if you stripped this thing of all its twist and turns, we’d still be pulling for these characters, because we like them that much.

As for the writing itself, it’s pretty solid. Kurtzman and Orci created a nice device that I really enjoyed. In general, I dislike unmotivated flashbacks because of their tendency to feel unnatural. Throughout the script, K and O use David’s seizures as a way to flash back to the day of the murder. It’s a little thing, but it plays nicely because it’s motivated by character (specifically – this character’s seizures). Always look for natural ways to move into your flashbacks, as opposed to just hitting us with them out of nowhere. It makes a difference.

The one thing that drove me crazy were Kurtzman and Orci’s use of underlined dialogue. Normally, this kind of stuff doesn’t bother me. But these two, for whatever reason, underline nearly every word of their characters’ dialogue (I guess to give it emphasis?). But instead of giving it emphasis, it gives us headaches, as we’re forced to change the way we read, starting and stopping so we can mentally annunciate the underlined words. It took me half the script to force myself to ignore it, and man was it annoying.

I’m sure some of you will be comparing this to the French film, and with that film nabbing a 93% approval on Rotten Tomatoes, I’m preparing for the barrage of reasons why this doesn’t match up to it. But I’ve never seen the film, so this was a totally new experience for me, and I think they hit it out of the park. Really great script.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive (Top 10)

[ ] genius

What I learned: The “found key that leads to the mysterious lockbox” device is one of the few things you can count on to ALWAYS WORK in a screenplay. Every. Freaking. Time! Cause we’re inherently curious about what the hell could be in that box. You can never go wrong with this device. (Just try and make sure what’s inside is something unique!).

TITAN WEEK – REVIEW 1 OF 5

Welcome to Titan Week, where we feature five scripts by writers who currently are or at one time were titans in the industry. What constitutes a titan? Maybe they’re that writer every producer in town calls when they need a rewrite on their 200 million dollar film. Maybe they’ve sold multiple million dollar spec scripts. Maybe they’re universally praised and respected. Maybe their style was so impressive they influenced an entire generation of writers. In order to keep things fresh, I’m going to let you suggest the last review of the week, as I haven’t chosen a script for Friday yet. So if there’s a particular script by a huge writer you think I should review, go ahead and suggest it in the comments section. In the meantime, let’s start off with one of the biggest names in screenwriting history – Shane Black. I’ll hand it over to Roger as he takes us back to a simpler time. A time where Pac-Man ruled and when Michael Jackson was cool…the first time. Here he is reviewing “Shadow Company.”

Genre: Horror, Action, Science Fiction

Premise: Jake Pollard is a forever-changed Vietnam vet, a pariah just scraping by in American society. When he learns that the bodies of six MIAs, found sealed in a Cambodian temple, are being shipped back home for a military funeral at the National Veterans Cemetery, he transforms from drifter to man on a mission. When the six MIAs resurrect and start killing everyone in the town of Merit, California, Pollard makes a last stand, revealing both his ties to the townspeople and his shadowy past with the MIAs.

About: Shane Black’s first script. Written in 1984. Got him his first agent. Optioned by Universal. After the success of Lethal Weapon, John Carpenter came on as director (this would have been his follow-up to They Live) and Walter Hill attached himself as executive producer. This draft is dated October 20, 1988 and is co-written by Black’s pal, Fred Dekker (Night of the Creeps, The Monster Squad). I’m not sure if Dekker was always a co-writer or if he came onboard to help Black write this particular draft. Do any of you dear readers out there know?

Writers: Shane Black & Fred Dekker

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

Jessica Hall. JESSICA HALL! Back again, now with click-able links! We decided to bring this outfit into the present day. Lots of adaptation-type news. This Rothman pitch sounds kinda interesting. A comedy-horror set in deep space? Can’t say it’s not original. The rest of the stuff doesn’t complete me unfortunately. :(

Universal picked up a pitch from writer Rodney Rothman for mid-six-figures. THE SOMETHING is described as an ensemble comedy/horror hybrid set in deep space. While this is Rothman’s first solo writing gig, he has several other projects around town and made his start as the youngest head writer in the history of “Late Night With David Letterman.”

Nick Pustay (RAMONA AND BEEZUS) will adapt the first book in Maggie Stiefvater’s YA series, SHIVER. Story centers on a bittersweet paranormal romance between a teen who becomes a wolf each winter and his girlfriend, who helps him find the secret to staying human.

VLAD, the re-imagining of the Dracula myth, will be rewritten by Scott Kosar (THE MACHINIST), shepherded by director Anthony Mandler. Actor Charlie Hunnam (SONS OF ANARCHY) wrote the original draft. Brad Pitt’s Plan B is producing for Summit.

Mike Newell (PRINCE OF PERSIA) will write and direct an untitled project about the mysterious death of former KGB spy Alexander Litvinenko. He’s working with 2009 Black List writer David Scarpa (LONDONGRAD). Project is set up at Warner Bros.

Hoping for a new franchise, Ralph Winter and Terry Botwick acquired the rights to Dean Koontz’s “Frankenstein” series. Project places the doctor — a socially prominent and successful businessman — and his super-human original creation in modern-day New Orleans. No writer has been announced.

Oscar nominated writer Geoffrey Fletcher (PRECIOUS) will write an untitled project about the true story of the 1971 Attica state prison rebellion in which 32 inmates and 10 hostages were killed. Doug Liman (JUMPER) will direct.

Writer David Scinto (SEXY BEAST) will make his directorial debut with NIGHT FLOWER. Ray Winstone has signed on to star.

Kevin Lima (ENCHANTED) will direct AVON MAN, written by Kevin Bisch from his pitch. Fox bought the project as a vehicle for Hugh Jackman, who plays a man who loses his job as a car salesman and becomes a successful Avon salesman.

Oscar nominated writer Oren Moverman (THE MESSENGER) will polish and direct ALL APOLOGIES, the Kurt Cobain biopic. David Benioff (BROTHERS) wrote the current draft for Universal.

Playtone producers Gary Goetzman and Tom Hanks are currently out to writers for the remake of the French film SUMMER HOURS. Pic tells the story of three children letting go of their childhood as their dying mother’s home is evacuated of their belongings.

Genre: Spy-Thriller

Premise: (from IMDB) When a group of villains destroy a CIA-operated safe house, the facility’s young house-sitter must work to move the criminal who’s being hidden there to another secure location.

About: This is a first time spec sale for David Guggenheim, but he’s not a complete foreigner to the business. David is a senior editor at US Weekly and, as Variety is reporting, the brother of Marc Guggenheim, one of FlashForward’s early showrunners. His other brother, Eric Guggenheim, may have given him some tips, as he’s a screenwriter himself, penning the 2004 film, “Miracle.” This particular spec sale is noteworthy as it’s the first big sale of the year (selling for 600k) and doing so without any talent attached. Between approving photos of whale-esque Kirstie Alley and Tiger Woods’ many mistresses, Guggenheim has another project he’s developing with McG titled, “Medallion.” Universal nabbed the spec after a multi-studio bidding war. Scott Stuber (The Wolfman) will produce.

Writer: David Guggenheim

Details: 111 pages (undated)

Matt Weston is an eager 28 year old worker for the CIA living in Rio De Janeiro with a Brazillian beauty who puts Matthew McConaughey’s baby mamma to shame. I say “worker” because he’s not quite an agent yet. In fact, Matt is barely above Ace Ventura on the company totem pole, relegated to the job of a “housekeeper” at a safe house. What this entails is hanging out at a special CIA approved “apartment” all day, awaiting any CIA agents who need a place to crash – sort of like a hotel room where you know you’re not going to be killed in the middle of the night (well, as we’ll learn, not even that is guaranteed).

On the other side of town is Tobin Frost, a 55 year old ex-CIA field officer. Imagine Jason Bourne in 20 years. That’s this guy. But Frost has gone off the grid for over a decade, and is believed to be selling CIA intel to anyone with a Swiss Bank Account or some juicy intel of their own. He’s apparently hit the motherload, as the latest information he’s acquired has him hunted by a lethal assassin named Emile Vargas. Frost may have been able to handle this guy a quarter of a century ago, but even the best have to admit when they need help. Problem is, the only nearby help is the very institution he’s betrayed, the American Embassy. So Frost does the unthinkable. He walks right into the Eagle’s Den.

The Americans send Frost over to Matt’s safe house until the CIA can get down here and extract him. But let’s just say Frost won’t have to worry about purchasing the weekly discount. The Safe House is immediately attacked by mercenaries we believe are led by Vargas. Frost and Matt somehow escape, and quickly find themselves on the run. Matt’s given orders to bring Frost to a second [not so] safe house four hours away, but Frost seems to have other plans, namely to get the hell away from Matt and out of Rio.

The script shifts its focus to two things after that: Action and more action. Safe House at times feels like one gigantic action sequence, and I have to admit, it’s written quite well. Guggenheim follows the unwritten spec rule of keeping everything lean and rarely, if ever, burdening us with a 4-line chunk of action. In fact, almost every action description is 2 lines or less, making sure that things read faster than a Shani Davis 200 meter run.

During all this action, we get a nice debate going between the idealistic Matt and the cynical Frost, mainly on the merits of whether it’s worth it to be a CIA agent, but also on Frost’s reasoning for obtaining the information that’s gotten him into such hot water. Although Safe House never pretends to be anything more than a high-octane thrill ride, there’s some interesting discussion about idealism and trust, as well as the many shades of gray involved in the spy world. In fact, after a few pow-wows with Frost, Matt starts to wonder if the agency he’s held in such high esteem is as honorable as he once believed.

While the action does get repetitive at times, Guggenheim keeps it fresh with Frost repeatedly escaping Matt, and Matt having to go capture him again. And even though Frost is to Matt as Kobe is to Luke Walton, a nice twist is that Frost was Matt’s case study back at the Farm, so many times, Matt knows where Frost is going to be before he does.

Safe House is a fun spec, but there were a couple of things that bothered me about it. First off, I knew nothing about safe houses going into this script, and I can say that I don’t really know much about them now either. I mean, if you asked me the biggest lesson I learned about safe houses, it would be that they’re not safe at all! Every safe house they go to is breached within minutes. There are obviously extenuating circumstances here, but even taking those into account, from the way these places were described, they seemed to be no different than a local hotel room, except for a CIA officer holding court. I guess I expected them to be more heavily fortified or something. Or have some special qualities. Maybe a better explanation of what these things are in the next draft would be helpful.

I also would’ve liked a few more twists and turns before the final act, and a better explanation for why Frost flipped on the agency. His explanation was a little too general for my taste (his reasoning amounted to that the agency lies too much). A specific event that triggered this decision would make his motivation more personal, and his character deeper and more interesting as a result.

But those things are by no means deal breakers. Like I said, the script is still fast-paced and fun. And the specific reason behind why Frost is being chased plays out to a satisfying conclusion.

So why did it sell? Well, all we can do is speculate, but I’ll give it a shot. It did exactly what we talked about the other day in my article about surprise box office hits. It took a popular plot model, in line with the Bourne films, and added a twist, throwing a bit of a “buddy cop” angle at it. It also told the spy story from a unique perspective, that of the “safe house,” and I don’t think that’s been done on the big screen yet.

Safe House is worth the read.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: So lean. People don’t understand why spec scripts have to be so lean. It’s because an unknown to little-known writer is basically given ten pages of leeway before a seasoned reader mentally checks out on them. You have to be lean to survive, to prove to your reader that you won’t burden them with a bunch of unnecessary nonsense. You’re saying right away: Listen buddy, I’m not going to waste your time. I’m keeping it bare-bones. This is never as important as it is in the action genre, where everything has to move FAST. How are you going to convey a fast action script with huge paragraph chunks? Finding a four-line paragraph in this script was like trying to find a salad in New Orleans. Spec scripts gotta be leeeeaaaaan.

Genre: Thriller

Premise: A group of oil drillers on a plane ride home, crash in the arctic tundra, where they become hunted by a vicious pack of wolves.

About: Many probably know Carnahan as the upstart testosterone-filled director who broke out with “Blood, Guts, Bullets, and Octane.” He went on to make the well-received “Narc,” which led to a pre-couch-hopping call from Tom Cruise to become the next director in his Mission Impossible super-franchise. Things fell apart, Carnahan followed up with the all-over-the-place dud “Smokin’ Aces,” and that promising future seemed to be slipping away. Thank God for the ghost of Mr. T, because Carnahan jumped onboard the director-for-hire train and took on The A-Team. It was there that he apparently pitched Bradley Cooper his long gestating project about a group of plane crash victims trying to survive a pack of wolves. Cooper signed on and the movie is apparently a go (though where in the Bradley Cooper go-picture cycle it is, I’m not sure).

Writers: Joe Carnahan and Ian Mackenzie Jeffers (based on the short story ‘Ghost Walkers’ by Ian Mackenzie Jeffers)

Details: 120 pages (6/21/07)

Plane crashes.

Wolves.

People trying to survive.

The Grey is a dark eerie thriller that deals with the most primal of human experiences: survival. Oh, and it does so in a way that puts all recent survival stories to shame. Because this script rocks.

We’re in the Arctic Tundra. An oil drilling station up in the coldest regions of the world. When your company gets up near the equator, you don’t exactly attract the lawyers and doctors of the world. You get the ex-cons, the fugitives, the murderers. The people no one else will accept.

In the middle of it all is Ottway, a sad, frustrated, conflicted man who it so pains to be away from the woman he loves, that he simply can’t take it anymore. Combine that with being out in this vast depressing ice desert, stuck with all these cro-magnums, sunlight peeking out two hours a day at most, and you understand why he’s out here, away from the other men, with a gun to his head, considering ending it all. But something…some unknown force…brings him back from the edge. He’ll live. At least for one more day.

Lucky for him and the others, the company is flying the team back to Anchorage for a little recuperation. So everyone jumps on a 737, and they take off into a blizzard. Ottway drifts off, but less than an hour into the flight, there’s a large jolt, a twist, a turn, metallic wheezing, and the plane goes tumbling down. Twisted metal, fire, fuselage everywhere. Almost everyone’s dead. Just a handful of men survive. There’s Ottway, Luttinger (a bear of a man), Flannery (a sort of Bill Paxton type from Aliens) and Pike (the troublemaker), along with a few others.

Nobody’s able to keep their shit together. They are out in the middle of the North fucking Pole, employees of a company they know is too cheap to send out a rescue team to find them. But the only one who understands the true severity of their situation is Ottway, and he quickly takes charge. They need to set up a fire and they need to find food. Fast. As the others gradually slide out of shock, they begin to notice they have visitors. Wolves. Off in the distance. Staring. Pacing. Observing.

But these aren’t ordinary wolves. They’re bigger. More viscious. Unafraid. A genetic result of being forced to hunt bigger pray out here in the middle of nowhere. So they’re stronger. And they’ve never seen humans before. So they’re not afraid of them. They simply see them as another animal species invading their territory. And for that reason, they need to be killed.

And that’s exactly what they start doing. Instantly picking off our men, one by one. At first they wait for them to walk off alone, to go the bathroom. But soon they’re impatient with even that approach, and literally run into the group, grabbing their prey, and pulling the helpless men back to the pack, as they’re chewed apart alive.

It would be over much quicker if it weren’t for Ottway. He’s been out in the middle of nowhere before. He’s hunted animals. Wolves in fact. He understands them. And he’s their only chance at survival.

And the assessment is that out here, they’re toast. They need to get to the forest, where they’ll have cover. But if dealing with hungry killer wolves weren’t bad enough, the lawless Pike disagrees with nearly everything Ottway suggests. Pike wants to be the leader here, and his continual insubordination is threatening to kill them from the inside before they’re killed from the outside.

There are no big plot twists here. No surprises. No trickery or unique structure. It’s a very simple story. Group of Men vs. Group of Wolves. Battle for survival. And what makes it so compelling, is that the men are so grossly overmatched. They’re out of their element, starving, freezing, and the only one that understands the gravity of their predicament is a man that just yesterday wanted to end his life.

What I loved about The Grey was just how realistic it all was. You could feel the ice on your fingers. You could hear the wind kicking up the snow. And Carnahan and Jeffers supplement it with an “in your face” style full of italics and underlines. Normally that stuff annoys me, but here, it feels appropriate, as it embodies the immediacy and second-to-second struggle these men are going through.

And there’s something about Ottway that just makes you root for him. I love characters who want to end their life, only to be thrown in a situation where they must fight for it. Outside of the irony, it’s moving to see that moment a character realizes just how valuable life is. Ottway spends much of the opening speaking in voice over and his words are so real, so intense, they pierce you, bonding you with this man forever. As the odds become stacked higher and higher against him, you pray that beyond all reason, he’ll somehow find a way to survive, to find shelter, to find help. And yet, instinctively, you know no one’s coming to help him.

And then of course there’s the wolves. Oh the wolves. They’ll do what no other wolves would dare do. Run right into the pack, snatch you away, and chow on your throat as they drag you back to their kill den. This ain’t the French-kissing Taylor Lautner kind of wolf, nosiree. But the most terrifying of them all is the Alpha Male, the wolf that’s even bigger than all the other abnormally large wolves. Watching him observe these men from a distance, seeing eyes that almost appear intelligent, plotting, is what brings the reality of this situation to bear. And one of the cooler threads was the parallel between the alpha male relationship to the wolves in the wolfpack, and the alpha-male relationship to the humans in the human pack. As we jump back and forth, we realize these carnivores aren’t that much different from each other. It was all just done to perfection.

If there’s something that can be improved, it’s probably the secondary characters. Outside of Flannery and Pike, none of the other men stood out. And there’s a lot of places you can go with a pool of murderers and ex-cons. I thought that could’ve been fun to explore. But this is a 2007 draft, so I have a feeling they may have addressed that issue. Still, I hope they haven’t messed with anything else. This was an intense harsh thrill-packed ride from cover to cover, and I think it works perfectly the way it is.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Voice over is one of those things that, unless you know what you’re doing, you just shouldn’t fuck with. But when done well, it does a great job of quickly connecting you to the main character – helping you identify with and care for them in a manner that’s just not possible without hearing their thoughts. I dare you to read the opening 10 pages, hear Ottway’s voice over, and not sympathize with him, not want to root for him.