Genre: Action/Revenge/Comedy

Premise: Blasting out of prison after being double-crossed by the Mastermind of a heist, a Demolition Expert uses his genius with explosives to enact revenge on the Caper Crew who set him up while simultaneously picking up the pieces of his personal life.

About: The controversial screenwriting talent, Colin Bannon, he of the many wild high concept ideas, is back with another script. This is one of two scripts Bannon had on last year’s Black List.

Writer: Colin Bannon

Details: 115 pages

Colin Bannon reminds me of Mattson Tomlin and Max Landis, two writers who unapologetically seek out big juicy concepts then proceed to write them as fast as possible.

What Bannon has going for him is that he’s the most talented of the “high concept three.” How do we know this? Cause he’s written the best script of the trio – “Birdies,” a pitch-perfect deconstruction of weirdo influencer families. It’s that script that gives me hope every time I open a Colin Bannon script. But I’ll be honest. I haven’t seen Bannon put in that level of effort since Birdies.

Let’s see if that changes with The Demolition Expert.

Gus Bender is the demolition expert on a team of heisters. We meet him with his buddy, Joey Fix, “the mastermind” of the heist, as they break into the “Mind Lab” skyscraper where the CEO, Lazlo, keeps all his most precious items.

They coordinate with Wolf (hacker) and Smoke (driver), as well as their inside man, Stick (a master pickpocket). Using their time-tested abilities, they make their way into Lazlo’s abandoned office where Gus uses a new bomb of his that doesn’t create an explosion to break into Lazlo’s vault. They quickly take 60 million dollars worth of diamonds and they’re out.

Back at the warehouse rendezvous point, where they bring the stolen items to the investor, Gus goes to grab something in the back room, and when he comes back, everyone is gone. Seconds later, a SWAT team shows up and arrests Gus, who goes to prison for ten years.

During that time, Gus plans his revenge. But you have to understand that a demolition expert’s revenge is a little different than a normal citizen’s revenge. Gus is going to blow up everyone who screwed him over, one by one.

He starts with Lazlo’s personal assistant, Travis, who he blows up in a bank. He then moves to the investor, Bank, and blows up his entire casino. He then sets his sights on Smoke, who’s become her own tech CEO. But it’s clear that Gus isn’t getting any satisfaction from these kills. The only person he truly cares about blowing up is Joey. But first he wants to find out why Joey made him the fall guy.

It turns out that Joey will be selling a violin he stole from Lazlo (they waited 10 years for the heat to die down) at a high-end private auction in a few days. Getting to that auction is the only chance Gus may have to enact his ultimate revenge, a revenge that will make even Oppenheimer jealous.

Welcome to one of the wackier screenplays I’ve read all summer.

This one is ka-raaaaazy with a capital “K.”

Where do I begin?

Let’s start here. When Gus is in prison, he gets beat up every day by his giant cellmate. And, every beating, he gets a tooth knocked out. He collects these teeth in a little tin. We have no idea why.

When he finally gets out, he tricks Travis into thinking they’re going to take down Joey together. But Gus only has revenge on his mind. So, while they’re driving, Gus guns their car into a bank, bangs Travis’s head against the dashboard dozens of times until all his teeth are gone. Then Gus brings out the tin of his teeth from prison and shoves them into Travis’s mouth. He then jumps out of the car, leaves the building, detonates the car bomb… ALL SO THAT THE POLICE WILL IDENTIFY TRAVIS AS GUS BECAUSE HE HAS GUS’S TEETH.

I don’t know if that’s the most genius thing I’ve ever read or the most ridiculous, lol. But it’s a great indication of what kind of script you’re getting into with The Demolition Expert.

There is no shortage of zaniness here.

When Gus finds Wolf, it turns out she’s started a mindfulness app that measures your resting heartbeat to keep you “mindful.” So what does Gus do? He hooks a bomb up to the app (somehow ahead of time), and then corners her, explaining that if her heart rate exceeds 183, the bomb blows up. This makes Wolf nervous, so her heart rate keeps rising, which Gus draws her attention to, which makes her heart rate rise even more. And now it’s a desperate race to calm herself down.

Later still, Gus finds Smoke, the getaway driver, who is in the middle of a NASCAR race. He hacks into her headset and explains that he’s rigged her car to blow up if it goes below 200mph. “It’s like SPEED,” he tells her. “But faster.” He then explains that her only salvation is to leave mid-race and get to Santa Monica, never dropping below 200 mph. An impossible feat that she attempts to achieve anyway.

Again, I don’t know what to make of these choices. I don’t want to be disrespectful but they often feel like something a 16-year-old would come up with. Maybe that’s good. Cause that’s the demo you want coming to the movie. But even when you’re writing for younger people, the craziness has to have some level of sophistication to it.

Look at Pixar movies. They’re written for 10-year-olds. But if 10-year-olds had written those movies, they’d be packed with a bunch of farting and burping and silly ideas that didn’t make sense.

I mean, Michael Bay makes an appearance in this movie. Or there’s a moment where a demolition expert, Mary Beth, approaches Gus and tells him that they did the same thing to her. She then offers him to join her on an island for the rest of his life. A woman he’s known for 30 seconds. That’s not sophisticated writing. That’s first draft writing.

That careless recklessness permeates the script.

And yet, to Bannon’s credit, it never totally derails the experience. There’s just enough of a “good time at the movies” feel to the script that you overlook its weaknesses. This is clearly Bannon’s modern-day take on Speed and it’s probably how a modern-day version of Speed would look like. There wouldn’t just be one scenario (a bus that couldn’t drop below 50 mph). The social media generation needs more stimuli, which is what The Demolition Expert gives you. It entertains you with multiple bomb situations.

Every audience member has their own threshold for suspension of disbelief. Some of us need airtight logic to keep our diselief going. Some of us only need jokes and silliness. The Demolitions Expert is much closer to the latter than the former. But, then again, so was Speed. So mileage will vary here.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Scenes that cut between more than two characters involved in a complex situation that needs a lot of description are going to leave a lot of readers cold. These scenes work great on screen. But on the page, they require a lot of concentration to follow. It’s more about us figuring out what’s going on than it is about us being entertained. So this opening heist scene in The Demolition Expert was work to me. It was not enjoyable. I prefer simplicity. The opening scene in Drive covers similar subject matter but it focuses on one singular character in one singular situation – a getaway driver driving away.

Obviously, in Mission Impossible and Fast and Furious type movies, you will sometimes need to write these scenes. But I encourage writers to both simplify them and zero in on the most entertaining component of the scene and feature that. We’d rather read about Ethan Hunt dangling from wires in a secured CIA computer room where one bad movement gets him and his team caught than cutting between 10 different characters all chiming in, where we only understand half of what all of them are contributing. Reading should NEVER FEEL LIKE WORK. It should ALWAYS FEEL LIKE PLAY. Let that mantra guide you.

Do we have a new Top 25 script on our hands!!?

Genre: Thriller

Premise: After a devastating wildfire wipes out a small California town, a teenage girl is missing and presumed dead. A year later, an obsessive mother and cynical arson investigator begin to suspect that she’s still alive…and in the clutches of a predator.

About: Dan Bulla is one of the newer writers on Saturday Night Live, joining the longstanding sketch show in 2019. He also wrote an episode of the Pete Davidson show, Bupkis. This script finished on last year’s Black List.

Writer: Dan Bulla

Details: 111 pages

Mark Ruffalo for Nick?

Mark Ruffalo for Nick?

It is the most wonderful time of the year.

No, I’m not talking about the return of football. I’m talking about the U.S. Freaking Open! I’m currently bouncing around between watching 128 first round matches, having the time of my life.

It was during this trip to nirvana that I thought to myself, “You know what would be nice? Reading a script about a forest fire!” Hey, I can’t defend how my mind works. It does what it wants to do and I try and keep up.

Little did I know I’d be stumbling into a bona fide banger of a screenplay!

40-something Jessie lives in Avalon, California – one of those small Northern California towns in the middle of endless forests. And on this morning, it’s a bad day in Avalon. A massive forest fire creeps up out of nowhere, causing a mad dash to get out of town.

Jessie and her husband, Ken, are assured by the local police that the high school has been evacuated, meaning that their daughter, Wendy, is okay. Still, they barely escape and get to the rendezvous point, where they learn the devastating news that Wendy secretly ditched school that day.

Cut to Wendy and a couple of her friends goofing off in the forest when the fire approaches. They make a run for it but get split up, and Wendy finds herself on a road that is blocked in both directions. Just before she’s about to die, a red pickup truck arrives and a man named Randy saves her.

Cut to a year later and we meet Nick, a private fire investigator. Nick is in Avalon to meet Jessie, who says she has evidence that the fire was not, indeed, caused by a downed electrical generator, but rather by arson. Nick has a lot invested in Jessie’s claim because he’ll receive a giant windfall of cash if he can get the electric company off the hook.

Unfortunately, Jessie seems flat-out crazy these days. She lives in an RV in this shell of a town, collecting burned-up debris in the hopes of proving there’s more to this fire than meets the eye. Nick knows that her theory is weak from the get-go and considers turning around and leaving immediately. But Jessie’s emotional plea to help her figure out how her daughter died gets Nick to stay.

The next day, Jessie shows Nick a mysterious gray line she found in the burnt-up forest. Now Nick is interested. This line implies that the fire was started by arson. Which means somebody planned this. He further figures out that Wendy may not have died after all. Could these two things – the arson and Wendy’s disappearance – be related? And, if so, who, in town, has her? Nick and Jessie will have to team up to find out!

Let me say that this is the first script I’ve read in months where I thought I was a lot earlier in the script than I was. I thought I was on page 60 and it turned out I was on page 85! Usually, it’s the opposite. I think I’m on page 60 and I’m on page 20.

That’s screenwriting code for: this script was awesome.

I liked the script even before I opened it. It’s a fresh concept. We don’t usually see serial killers and wildfires in the same story space. It’s a unique combination. More importantly, it rewrites the investigation narrative. Usually, when we read about a killer or an abductor, it takes place in a city, which means that every investigatory beat in the story is one we’ve already seen before.

Here, the investigatory beats are all unique because we’re in a bunt out town in the middle of nowhere. We’re not going to apartments in Brooklyn asking cousins when the last time they saw Jenny was. We’re in a forest examining dead animal carcasses. I can’t emphasize enough how important this is. Readers read the same stuff OVER AND OVER again. So if your plot provides a world with a bunch of fresh scenarios for your characters to engage in, you’re up on every other screenwriter in the business.

As always, these scripts depend on authenticity. I always say to writers – if you’re writing about a specialized subject matter, you better know a lot more about that subject matter than I do. If I think we know that subject matter evenly, I’m done with your script. Cause I know you didn’t do any research, which means you’re not trying. I don’t have time for writers who don’t try.

I LOOOVED the opening forest fire scene here. It was SOOOOO intense. And the level of specificity to it was impressive (the way this fire spreads sounds eerily similar to what happened in Hawaii recently – and this script was written a year before that happened). There’s this moment where they’re desperately trying to get out of this logjam of cars and they finally break through and they’re racing against the smoke and they look over and there are these deers who are right next to them, also trying to escape. It felt so specific, like the writer was fully tuned into the sequence.

The writer also knows how to navigate the nuts and bolts aspects of storytelling. For example, there’s this early scene with Nick where the writer wants to establish that Nick knows what he’s talking about. You do this in screenwriting because it gets the reader on the character’s side. Readers LOVE when the character knows something that the average person doesn’t.

There’s this moment where Jessie is trying to convince Nick that a bottle rocket was the cause of the fire. Nick takes a look at the bottle rocket and the affected area and says this: “There’s deep char on the right side of the trees. Minimal char on the left. Burns rising, right to left, steeper than the slope. Branches all bent in the same direction. Foliage freeze. That means the wind was blowing right to left at the time of the fire. No odor. No sign of accelerant. It’s burned on top, untouched on the bottom. That tells me that a fully formed, advancing fire swept over this area, right to left, at about six miles an hour. The bottle rocket didn’t start the fire. It’s just some litter you found in the woods.” If there was any doubt that this guy is a fire expert, this assessment puts it to rest.

And then there’s this little moment early on that told me I was dealing with a guy who KNOWS SCREENWRITING. Jessie gets Nick to stay one more day by telling him that, tomorrow, she’ll show him a piece of evidence that will prove the fire was created by arson. The day comes, Nick shows up at her place, and says, “Where’s the evidence?” And she says, “Change of plans. First you’re going to tell me what happened to my daughter.”

The words “change of plans” should be a part of every screenwriter’s vocabulary. Why? Because YOU NEVER WANT THE READER TO GET COMFORTABLE. You don’t want them having a sense of where the story is going all the time. “Change of plans” throws the reader off. Cause now we’re going in a direction that wasn’t a part of the original plan. It’s exciting.

Not that you have to use those exact words (“change of plan”) every time. It’s more about you, the writer, occasionally changing things up so you don’t stay on that same predictable path the whole story.

Oh, one more thing. In a lot of the scripts I read, the bad guys never get the deaths they deserve. They get these quick weak deaths where they don’t suffer at all. This bad guy gets a terrible death and it’s awesome.

All this adds up to a really good screenplay. One of the best – maybe even the best – scripts on last year’s Black List. Definitely check it out!

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive (Top 25!)

[ ] genius

What I learned: There comes a time in a lot of scripts where a character will remember something about their loved one and share that experience with another character. These memories are one of the best ways to separate yourself from the average writer. Cause most writers have these boring on-the-nose memories they have their character recall.

“Oh, I remember when Wendy was 7 and she fell in the pool and she didn’t know how to swim and so I jumped in after her and I pulled her out and she wasn’t breathing and I’ll never forget giving her mouth to mouth. I thought for sure she was going to die. But, then, at the last second, she let out a breath. And it was at that moment that I knew my daughter was a fighter.”

Note how unimaginative that is. Note how 99 out of 100 writers would’ve been able to write the same thing. Real memories are unique. They have weird details. They don’t go according to plan. And they rarely line up with the five cliched memories that most writers use in these instances. Note how different, even a little bit odd, the chosen memory Dan Bulla uses for Jessie when she shares a story about Wendy…

“One time, I sat in the living room all night, waiting for her to come home. Just absolutely fuming. She finally snuck in just before sunrise. Didn’t see me sitting there in the dark. She shut the door. Locked it without making a sound. Then she went upstairs, straddling the steps so the stairs wouldn’t creak. And I didn’t say anything. I just watched her. And I remember feeling lucky. Lucky to witness that. Because I was seeing her. The real her.”

Does anyone here know what a “screenplay movie” is?

A “screenplay movie” is a movie that actually resonates because of the screenplay.

Most of the movies at the top of the box office in the IP era are *not* screenplay movies. They’re Hollywood movies.

They’re designed to sell tickets and merchandise. Their impact is based more on the filmmaking – the big set pieces, the flashy production value, the huge star power – than anything that’s written on the page.

It’s not that writing these movies is easy. Far from it. Hollywood movies have their own set of challenges brought on by managing multiple points-of-view (the studio, the director, the actors, 20 different producers), many of which conflict.

Imagine receiving a note from the lead actor to make their character funnier then an hour later receiving a note from the head producer to make the lead character more serious. That kind of conflicting feedback is not uncommon.

But the bulk of Hollywood movies are about laying out a clear three-act structure and managing exposition so that the audience can clearly follow what’s going on. You are solving issues that are more technical than artistic, which is why these movies are less rewarding to work on and less rewarding to watch.

“Screenplay movies” put more thought into the characters, take more risks inside the plot, have more to say through their themes, and generally make you think and feel a lot more. They are designed to connect with you rather than whack you across the head.

Here is a list of the top 10 movies at the global box office in 2023:

1) Super Mario Bros — $1.36B

2) Barbie — $1.34B

3) GotGVol3 — $845M

4) Oppenheimer — $777M

5) Fast X — $705M

6) Across The SpiderVerse — $688M

7) The Little Mermaid — $568M

8) Mission Impossible7 — $552M

9) Ant-Man3 — $476M

10) Elemental — $468.6M

Surprisingly, five of them are screenplay movies and five of them are Hollywood movies. I say “surprisingly” because, usually, the top 10 is dominated by Hollywood movies. Do you know which ones are the screenplay movies? I’ll give you a second to make your picks.

The Hollywood movies on the list are…

Super Mario Brothers

Fast X

The Little Mermaid

Mission Impossible 7

Ant-Man 3

The screenplay movies are…

Barbie

Guardians of the Galaxy 3

Oppenheimer

Across The Spider-verse

Elemental

I know a lot of people loved Super Mario Brothers but let’s be real. It’s positioned as a product above all else. I wouldn’t be surprised if AI is writing all the Fast & Furious scripts at this point, the writing has become so insignificant. Did anybody even write The Little Mermaid? Aren’t they just using the same script as last time? Mission Impossible 7 isn’t as bad as Fast X in the writing department. But that franchise clearly prioritizes stunts over everything else. And then Ant-Man 3 is part of the Marvel machine. They probably have a studio exec leaning over a poor screenwriter’s shoulder saying, ‘yes,’ ‘no,’ ‘yes,’ ‘no,’ ‘rewrite that part,’ after every sentence.

With the screenplay movies, we’ve got Elemental, which I’m guessing is a screenplay movie because Disney puts a lot of thought into their screenplays for their original films, a valuable lesson they learned from Pixar. I haven’t seen Spider-verse but everybody tells me it’s got a great screenplay. I almost put Oppenheimer on the Hollywood list because Nolan prioritizes directing over writing. He’s more about his vision than getting the screenplay right. But he cares so much about these characters, and characters are the most important screenplay ingredient of all, that I decided to give him the benefit of the doubt. James Gunn has always been a screenplay-first guy. And you can tell he wants to move people with Guardians of the Galaxy. He doesn’t just want spectacle.

And then you have Barbie.

Barbie is an anomaly. It is a screenplay movie in a Hollywood movie body. Which is why, even though I didn’t agree with its message, I commend the writers for what they accomplished. Cause what they accomplished is amazing. They made a billion-dollar movie that actually makes you think, that actually gets people talking.

I told you, when I went on my recent family reunion, everybody in my family had an opinion about Barbie. That’s so rare these days. But it’s because the movie is a “screenplay first” concept that it’s resonating. It’s trying to say something rather than trying to draw audiences in. It just happened to be a product that everyone wanted to see. Which is how they used to make movies. They’d make gambles like this.

And for those of you who are saying, “Carson… blah blah blah… it’s Barbie. It’s international IP. Everyone was going to see this no matter what.” I don’t agree with that. I think if they went with the Hollywood version of this, it would’ve looked flat. It would’ve looked uninteresting. It would’ve still made money. But it would not have come anywhere close to 1.3 billion.

“Barbie” should be encouraging to every screenwriter out there. It shows you that when a good writer has a strong vision, they’re better at this than all the studio heads combined. The artist is the only one in the equation who wants to take risks. The studio and the producers hate risks. Which is why the movies they spearhead feel so average. They never hit you on an emotional level.

Here is this latest weekend’s Top 10 along with their categorization…

1) Gran Turismo – 17.3 mil/17.3 mil – Hollywood

2) Barbie – 17.1 mil/594 mil – Screenplay

3) Blue Beetle – 13 mil/46 mil – Hollywood

4) Oppenheimer – 9 mil/300 mil – Screenplay

5) Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles: Mutant Mayhem – 6 mil/98 mil – Hollywood

6) Meg 2: The Trench – 5 mil/74 mil – Hollywood

7) Strays – 4 mil/16 mil – Hollywood

8) Retribution – 3.3 mil/3.3 mil – Hollywood

9) The Hill – 2.5 mil/2.5 mil – Screenplay

10) Haunted Mansion – 2 mil/62 mil – Hollywood

I was rooting for Gran Turismo and happy for its first-place finish. Even though it’s a subdued winner, it should get director Neil Blomkamp another directing project. Whether that’s a good or a bad thing, we’ll find out. But a part of me still roots for him, at least until we get District 10. The movie just couldn’t overcome its benchwarmers status. The cast (Orlando Bloom?) makes you think that someone at Netflix made a mistake and accidentally put the movie in theaters instead of on the service.

Poor Blue Beetle. These DC movies can’t overcome their association with the former era of DC. Who wants to see a superhero movie that they know has no future? But even if that wasn’t the case, the CGI on this Blue Beetle guy screamed “cheese factor 700 thousand.” It just didn’t work. It was an ill-conceived superhero project from the outset.

The movie I was most intrigued by on this list was Strays. Not because I wanted to see it. But because it’s a physical manifestation of how confused Hollywood is right now. It used to be that if you pitched a movie like this in a room, the response would be: “A movie with real dogs that’s raunchy and R-rated? So you can’t bring kids, cause it’s too raunchy. And you can’t bring in adults because adults don’t want to see a movie about dogs on an adventure. Who’s going to show up to this movie???” The pitch would die before the writers could ask if the studio preferred two brads or three on their drafts.

But, these days, nobody knows what’s going to do well or not so they throw stuff at the wall. On some level, I admire it. It’s a bold move. But, in the end, it turned out the old school thought process was correct. This concept actively discourages both ends of the audience spectrum from seeing the film.

I’m just glad that, after looking the box office up and down this week that screenwriting still matters! I don’t know why I thought it didn’t matter at the top of the box office. I guess I assumed that the top 10 movies were always going to be machines that placed screenwriting at the bottom of the priority list. But it’s clear from Barbie’s success (as well as some of these other giant films) that if you want to really connect with audiences, giving screenwriters a concept and “getting the f**k out of the way,” a la Michael Jordan circa 1989 in Cleveland, is the best way to go. :)

Every second-to-last Friday of the month, I post the five best loglines submitted to me. You, the readers of the site, vote for your favorite in the comments section. I then review the script of the logline that received the most votes the following Friday.

If you didn’t enter this month’s showdown, don’t worry! We do this every month. The deadline for September Logline Showdown is Thursday, September 21, 10pm Pacific Time. All I need is your title, genre, and logline. Send all submissions to carsonreeves3@gmail.com.

If you need help with your logline, I’m here. I’d say that about 20% of the entries I receive have good enough concepts to make the Showdown but are plagued by loglines that are either too messy, too unfocused, too long, or straight-up have the wrong approach. If you want a logline consult, they’re cheap – just $25. E-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com if you’re interested.

SIX loglines this month.

Good luck to all the contestants!

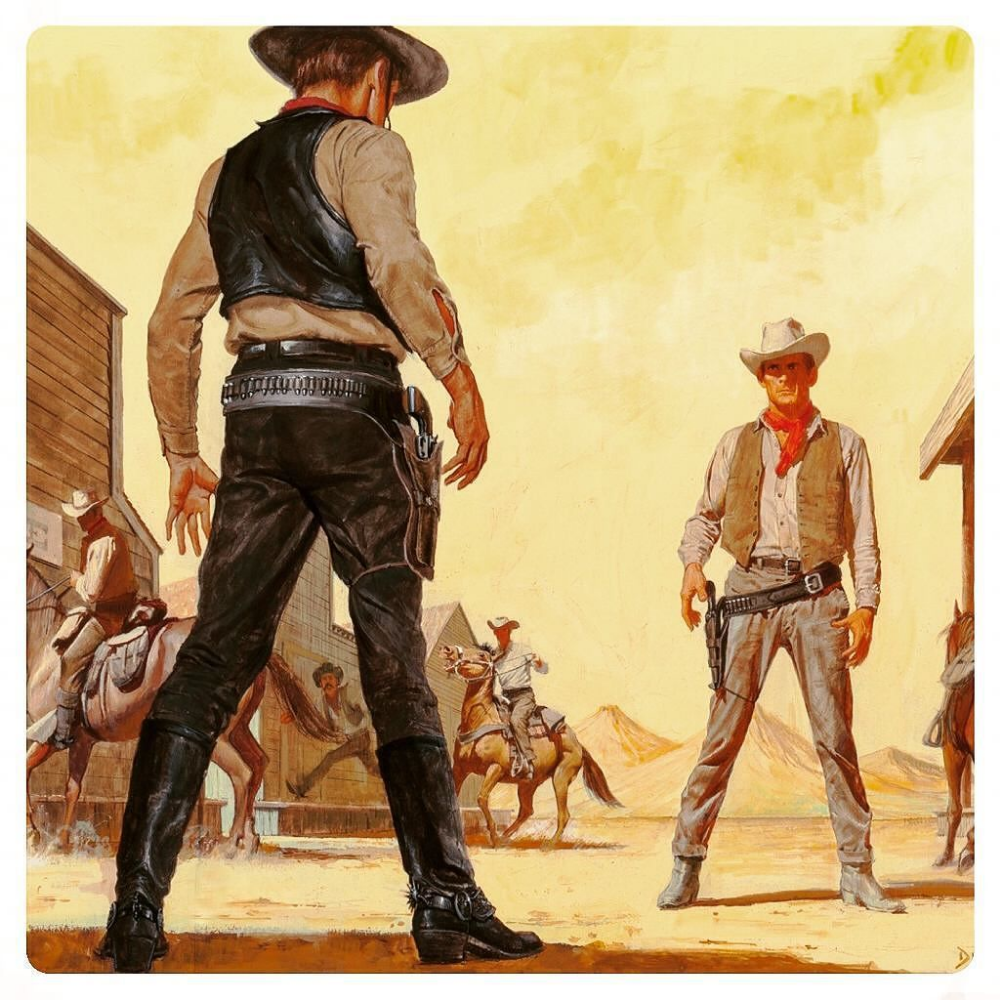

Title: Milk & Whisky

Genre: Western

Logline: Following the unusual death of his best drinking buddy, a lonesome drifter pursues refuge from old temptations and growing accusations by attending the frontier’s first rehab for alcoholics.

Title: Wayward Son

Genre: Thriller

Logline: When her estranged son returns and takes her grandson in the night, a veteran park ranger sets out to rescue him from the clutches of a mysterious cult deep in the Oregon woods.

Title: HAUL

Genre: Western

Logline: A female bounty hunter must transport two valuable corpses across an unforgiving, lawless wilderness with the help of a mysterious drifter.

Title: Matadors

Genre: Coming-of-Age / Horror

Logline: After ditching their field trip in a wildlife refuge, a group of overachieving prep school kids come under attack by a rogue, performance-enhanced fighting bull.

Title: The Patriotic Hitman

Genre: Action Thriller

Logline: A rogue government sniper assigned to kill a presidential candidate at a rally becomes a national hero when he spots a suicide bomber in the crowd and shoots him instead.

Title: trAiLIENS

Genre: Comedy/Sci-Fi

Logline: When a pencil-pushing FBI agent’s life is flipped ass-backwards by a UFO abduction, he launches a one-man probe to expose a mysterious Florida trailer park as ground zero for an imminent alien invasion.

GET THOSE LOGLINE SHOWDOWN ENTRIES IN! DETAILS BELOW!

The August Logline Showdown deadline is TONIGHT at 10pm. For Logline Showdowns, you send me a logline for a script. I then pick the best five loglines and they compete on the site with you guys voting. Whoever wins gets a script review the following week!

What: August Logline Showdown

Enter: Feature Screenplay Loglines Only

Deadline: Thursday, August 24th, 10:00 PM Pacific Time

Where: carsonreeves3@gmail.com

Okay, on to today’s topic!

Lately, I’ve been reading too many screenplays where I haven’t been able to connect with the characters. Whenever this happens, I go to this place where I think I can’t enjoy screenplays or movies anymore because I’m too deep inside the screenwriting matrix. I only see writers making choices rather than getting lost in a well-told story.

But then I’ll watch or read something good and realize that, no, it’s not that I’m emotionally dead inside. It’s that the writing isn’t good enough. The specific place where most writing goes bad is in the characters. The vast majority of the characters I read in screenplays are some combination of uninspired, boring, simplistic, and weak.

But the worst characters I see? Are the ones who are just *there*. That’s it. They’re on the page. They’re in the script. But they lack any sort of quality that pulls you in and makes you care about them. There are only 2 scripts on last year’s Black List where the writers wrote characters that I actually cared about. They were…

There were other scripts on the list that made me interested in the characters. But here’s why I’m writing today’s article. Making readers interested in your characters isn’t the same as making people *care* about your characters. It’s the difference between characters charged with TNT and characters charged with plutonium.

When you make the reader care about a character, they are EMOTIONALLY ENGAGED in your screenplay, which makes the story a thousand times more potent.

And writers just don’t know how to do this anymore. I don’t fault them for this. The biggest thing I’ve learned about screenwriting since I created Scriptshadow is that the hardest part to get right is the characters. That’s because you’re trying to represent a 659-dimensional human being in two dimensions. Our lives are hundreds of thousands of hours long. You think it’s easy to emulate that within two hours? It takes all sorts of writing knowledge to figure out how to condense the vast complexity of someone’s life into an artificial person who only exists for two hours.

But here’s the good news. I’m going to tell you how to do it. Right here. Right now. There are seven key things you gotta focus on. You will not be able to include all seven every time you construct a character. That’s because each script is different. But you should try and include as many as you can. Are you ready? Here we go.

A PAST

Give your character a past. Make that past as specific as possible. Because the more you know about that character’s past, the more you can include it in who that character is right now. If your character used to sell drugs on the street before becoming a big successful businessman, maybe he still has some of that “street” in him. Maybe he uses more slang. Maybe he’s not so prim and proper. If you know 19 other things about that character’s past and all 19 of those things have some echoes and remnants that have made it into who your character is today? I guarantee they’re going to be a more fleshed-out character than 90% of the characters the average script reader reads.

A SPECIFIC JOB

I just read this script where it wasn’t clear what the main character’s job was. I don’t think the writer knew. You can’t make this mistake. A character’s job is one of the easiest ways to add some specificity to them – to make them stand out from other characters. We spend half our lives at our jobs. So our jobs have a big influence on who we are, what we talk about, what we’re interested in, how much time we have for others. There’s a reality show I watch where this person used to be a bartender 12 years ago. And when he was a bartender, all he cared about was getting drunk and scoring chicks. In the latest season of the show, he’s become a bar owner. Now, all he cares about is where to score more investment money and ways to get more people to show up at his bars. Same person, but his job has created two completely different versions of him. For a writer to not be absolutely clear on what his main character’s job is and what that job entails and how it shapes his character is criminal. You’ve got to know!

DETAIL

I’m not exaggerating when I say that 99% of the scripts I read don’t include enough detail about the characters (specifically the main characters). Give me the details! Don’t tell me he’s wearing a “nice outfit.” Tell me what the outfit looks like. Is he wearing a blazer? If so, what color is it? That’s going to tell me something about him (if it’s lime green, I’m going to know that he’s eccentric). Is it a cheap blazer or an expensive one? Cause that’s going to tell me if he has money. Is it tailored or is it ill-fitting? That’s going to tell me if he cares about his appearance. And I’m just talking about his outfit here. Detail extends far beyond that. I want to know the details of his place. I want to know if he walks slow or fast. I want to know if he speaks with a lisp. Every detail you give is an opportunity for us to understand your character better.

ACTIVE

Make your character active. This is the one that most writers get right because it’s often a function of the screenplay. Most screenplays have a goal that needs to be achieved (Take down Thanos!). So your characters have no choice but to be active when they pursue this goal. Active characters are way more interesting than passive characters. Of course, there are rare stories that require a passive protagonist. That’s fine. But I promise you that for the 99.9999% of stories out there, you want your character to be active. It’s one of the easiest ways to make the reader connect with your hero. People like people who go after things.

A PERSONALITY

Ever go on a date with someone with zero personality? It’s misery, right? Same thing goes for movie characters. If they don’t have personality, we’re not going to like them. When I said above that I read too many boring characters, “boring” referred to “no personality.” Personality does not mean a super charming funny person, like Ryan Reynolds, by the way. I just mean they have to have some identifiable characteristics that make up a cohesive persona. They can be quirky, like Juno. They can be confident and assertive, like Ethan Hunt. They can be creative and ambitious like Tony Stark. They can be free-spirited, like Jack Dawson in Titanic. They can even be internal but tough, like James Bond. The point is, YOU NEED TO KNOW what those characteristics are. If you don’t know, there’s a good chance they’re going to be blank as a piece of paper.

A FLAW OR AN INTERNAL CONFLICT

Characters tend to be more interesting if they’re battling something internally. That battle might be a flaw (they’re stubborn). Or it might be an internal conflict (they haven’t properly mourned the death of a loved one). The great thing about flaws and internal conflict is that even when the story strops, your character’s struggle is still moving. You may be able to escape the bad guys for a while. But you can’t escape your thoughts. Or your weakness. It’s always there. So it’s downright silly not to include one of these for your character. I guarantee they’ll become more interesting once you do.

UNRESOLVED RELATIONSHIPS

One of the most relatable things on this planet are these universal struggles we have with other human beings. Old friends whose relationships we haven’t repaired cause we’re too stubborn. Mothers who won’t let their daughters stop thinking about getting married or having children. Divorced couples who wonder if they did the right thing. Being betrayed by someone you loved. Letting jealousy seep its tentacles into your marriage. Religious differences. Long distance relationships. Sibling rivalries. If you want the secret to pulling readers into a character, give that character a compelling unresolved relationship with another character. Take the most successful movie of the year – Barbie. Ken is in love with Barbie. He just wants to be Barbie. And she doesn’t want him. That unresolved struggle informs his entire storyline. It created an iconic character.

These are the ingredients. It’s up to you to decide how many to use and how to mix them. I encourage you to try and include all seven. Because the biggest mistake I see writers make when it comes to character is that THEY JUST DON’T TRY HARD ENOUGH. They don’t put in the effort. I read some scripts where I can tell the writer didn’t take a single minute before writing the screenplay to think about who their protagonist was. Trust me when I tell you, if you do that, that’s exactly how that character will come off to the reader – as someone who a writer did not put any thought into.

As I’ve said before, a movie can survive an average plot. It cannot survive an average protagonist.

Good luck and see you tomorrow for Logline Showdown!