It’s no secret that the industry is going through a transition.

The move away from original concepts at the box office as well as the rise of streaming has confused the marketplace in ways that probably won’t be settled for another five years.

The best way to explain it is that streaming has tried to pick up the slack on the original concept front and the results have been a mixed bag. We’ve gotten red-headed step-children like Ghosted, Red Notice and The Gray Man, which are more “shy concept” than “high concept.”

But there’s also been some golden children. Army of the Dead comes to mind. The Tomorrow War. Palm Springs. With these movies, we’re talking legitimate big ideas, the kind of “spec-y” material that gets industry folks jazzed up.

But I must be honest in saying that I’ve been questioning the value of “high concept” (or “flashy concept”) lately. It used to be the highest form of currency an unrepped writer possessed. Nowadays, the kind of script that gets a writer noticed is muddier than ever.

Take a movie like Extraction, on Netflix. Good movie. But how reliable is it that such a nuts-and-bolts action spec is going to get you noticed? That film was dependent on its direction to work. It was the furthest thing from a script-friendly concept.

You also have these screenwriting success stories that revolve around voice. Christy Hall, who wrote “Get Home Safe.” Shay Hatten, who writes all the John Wick stuff. He broke out because of his sixth gear writing style. Simon Rich, who’s positioning himself to be the next Charlie Kaufman. Emerald Fennel, with her eerie revenge story, Promising Young Woman.

So then, should writers forgo concept and write something that best showcases their voice?

The answer to that is a big fat “no” and I’ll tell you why. Because the one thing that has been true of Hollywood ever since its inception is that NO ONE WANTS TO READ YOUR SCRIPT.

They don’t. I love reading and I can’t even read your script. Not because I don’t want to. But because I’ve got a million other scripts to read so I don’t have time.

Now imagine someone who doesn’t like reading at all! How do you get them to read your script?

There are only four ways.

- Already have a relationship with them.

- Someone they respect must recommend the script to them.

- There’s a monetary benefit to reading the script (an agent reading a project that already has funding to see if it’s right for their actor).

- It’s a really good idea.

We know we can’t do anything about number three. And both one and two are dependent on you getting the script to someone in the first place. Which leaves us with number four. You have to come up with an idea that entices readers to want to read your script. And it has to be the best idea possible because, as we’ve established, nobody wants to read your script. So you have to make your idea irresistible.

I don’t think writers internalize this truth. A good way to cross that barrier is to imagine yourself pitching the script to a friend. That’s where you really know if your idea is a winner or a dud. A friend catches you off guard and asks you what your script is about. No matter how well you explain it, it always ends up sounding boring (or weak, or bad).

Most writers live in Delusion Land when it comes to their movie ideas because they’re biased and have an emotional attachment to their ideas. Telling them their idea is bad just makes them want to prove you wrong. So let’s use this as an opportunity to remind you what makes for a good concept.

STRANGE ATTRACTOR

There are a lot of movie ideas out there that sound decent at first. Yet there’s clearly something missing. That thing is usually the strange attractor. The “strange attractor” is the element in your idea that’s unique enough to set your concept apart from others. A kid who gets kidnapped by a local serial killer and imprisoned in his basement is a dime-a-dozen concept. A kid who gets kidnapped by a local serial killer, imprisoned in his basement, and has access to a phone that can connect with all the killer’s previous victims is a concept with a strange attractor.

MARKETABLE

Would it require mountains to be moved to market your idea? Is your idea about a 19 year old selling bed mattresses in 1997? Is it about two nuns questioning their faith? Is it an impressionistic account of an American family’s rise and fall over two decades? I’m not saying these movies don’t occasionally break out. Aftersun is about a woman’s memories with her dad when she was 11. It would definitely fall into the “unmarketable” category. But remember that you’re not pitching people an already-finished movie. You’re pitching them a script and trying to get them to read it. How many of you have even seen Aftersun? If you haven’t seen a beloved movie that’s already finished and available for only 5 bucks, why would you think anyone would want to read your unmarketable premise, which *IS NOT* a movie that won a dozen awards? If you’re going indie, at least try and get *ONE* marketable element in there. Even Bones and All had cannibals. Even the indy-est film ever, “The Whale,” had a 600-pound man. Even “Pig,” had a truffle pig. Think about how your movie would be marketed to know if your average reader would be interested in reading it.

THE ‘ALMOST’ CONCEPT

The ‘almost’ concept is the fake Rolex of the screenwriting world. It looks good at first. But the closer you inspect it, the less it holds up. It basically amounts to using a lot of high concept buzz words that don’t add up to anything real. Here’s an example: “An advanced AI algorithm figures out a way to create the first real vampires, werewolves, and zombies, which are inadvertently released into the population.” Look at all the high concept buzzwords here. “Advanced AI algorithm.” “Vampires.” “Werewolves.” “Zombies.” It must be a good idea, right? No. Because it’s an inelegant collection of surface-level elements that lack a compelling narrative.

IRONY

Irony is the biggest concept cheat code you’re ever going to find. It’s actually quite difficult to come up with a good ironic concept, which means that, when you do, your idea is going to stand out. One of the reasons that The Lost City was a hit was because it had a fun ironic premise. The dopey clueless model on the book cover of all her romance-adventure novels is determined to save the author when she gets stuck in a real-life adventure. The great thing about ironic movie ideas is that they’ve proven they can stand the test of time. 1983’s Trading Places is about a poor guy who trades places with a rich guy. We all love watching a rich person who’s all of a sudden penniless. Or a poor person who becomes a millionaire. We all love irony.

PUSH THE ENVELOPE

Not everyone likes to write big flashy movies. But, if you’re going to write something smaller, you have to find ways to turbo-boost the idea or I’m afraid people just aren’t going to be interested. Promising Young Woman walked a dangerous line with some of the scenes in the script as well as its main character’s actions. Black List script, Magazine Dreams, about a disturbed man obsessed with bodybuilding, gets uncomfortably gnarly. If you’re thinking of writing an idea that’s both small and lightweight, you’re making things sooooooo hard on yourself. If you’ve got one of the things listed above (irony, strange attractor, marketability) it can work. But if not, you need some edge. Look to push the envelope, usually with your main character. The Joker is the ‘best case scenario’ outcome of this strategy.

In the end, idea construction comes down to creativity. It starts with inspiration – you saw something and it gave you an idea for a movie. You then have to be honest with yourself. Do I have a legitimate movie idea here? When I was in high school, I saw my friend’s brand new litter of puppies and I thought, “That would be a great idea if the puppies were all real smart and could communicate with humans.” So I came up with a drama idea (not comedy idea) about smart puppies. Again, just cause you’re inspired doesn’t mean it’s a good idea.

Once you have the idea, come up with the best way to present it. I’ve told this story before – screenwriter Ben Ripley’s first six drafts of Source Code centered around a detective trying to figure out why a train crashed. Once Ripley moved the script inside the train, in the mind of a character who keeps waking up on it every eight minutes, the idea came alive.

And from there, you have to field-test it. Ask people who have told you before that you have bad ideas what they think. If several of them are really pumped up about the idea, you probably have something on your hands. If everyone’s lukewarm or gives you that pleasant, “Yeah, it’s not bad” response? Or starts asking a lot of confused questions? Throw the idea away. There isn’t time for you to waste on an idea that you’ll find out six months down the road wasn’t any good in the first place.

Feel free to field test ideas here in the comments. I’m going to ask for an amendment to the field-testing, though. If you are replying to someone’s idea, you must rank it on a 1-10 scale. BE HONEST. We’re trying to help people here. Not send them off on a wild bad-movie-idea goose chase. And writers? I’ve found that most people rating you on a 1-10 scale will rate you one number higher than what they really think. Just because most people don’t want to be mean. So if someone gives you a 6 out of 10, they’re probably giving you a 5 out of 10.

You can come to me as well. I will give it to you straight. My logline consults are $25. You can e-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com if you want one!

For reference, I’ve done a few hundred logline consults this year and I’ve given about ten 8’s. A couple of 8.5’s. No 9’s or 10’s. And I use “7” as my floor for whether you should write the script or not.

Genre: Superhero/Comedy

Premise: (from Black List) When a washed-up superhero gets betrayed by a Mexican government, he must lead a populist social movement to fight the Narcos, topple the government, and free the people.

About: We’ve got another Black List script here, this one near the top with 15 votes. Miguel Flatow is a Mexican native who went to NYU for Creative Writing. In 2021 he wrote and directed his first feature film, called For Diego, which he shot on an iPhone for 70 grand.

Writer: Miguel Flatow

Details: 113 pages

Jonah Hill has the comedic and dramatic chops for Captain Bald Eagle

No need to beat around the salvia clevelandii. This script wasn’t my jam.

It wasn’t a bad script. It moved along at a nice pace and everything. But it’s so uneven that it’s hard to get a handle on.

The read got me thinking about Black List scripts and which scripts make the coveted Black List (a yearly list of the best scripts in Hollywood). It’s a question I’ve been asked a million times before. “What’s the difference between a Black List script and my script?” In other words, what do I need to do to get my script on the Black List?

It’s a hard question to answer because the margin between Black List writers and the average aspiring screenwriter with at least five scripts under his/her belt is thinner than ever. If you held a blind vote between a lower-ranked Black List script and a veteran amateur script, the guess on which one was the Black List script would probably come back at 50/50.

So then let’s get back to the question. What’s the difference? What is it that the Black List script has that your script, which hasn’t made the Black List, doesn’t have?

Well, the best way I can think of to explain it is through a tennis analogy. A lot of you probably don’t watch college or professional tennis. But I watch both. And when I’m watching college tennis, I marvel at how good the players are. Almost all of them have serves eclipsing 120mph. They all have huge forehands. They have consistent and even, in some cases, aggressive backhands. If a weekend club player played the number 2 tennis player at UCLA, they would lose 6-0, 6-0.

However, the second you put a college tennis player up against a professional player – a guy in the top 100 – he’s the one who’s overmatched. He’ll definitely look respectable out there. But he’s still going to lose to the pro in straight sets.

The question of what’s the difference between a Black List writer and a seasoned amateur writer is similar to the difference between a pro tennis player and a college tennis player. And what that amounts to is that both players do everything well. But the pro player just does everything a little better.

The college player has a 120 mph serve. The pro player can buzz one in there at 130. The college player can sit in the pocket and groove the ball back through a 15 ball rally without getting tired. The pro player can stay in there for a 25 ball rally and is still be as fresh as he was at the start of the match. The college player can belt out 10 winners on their forehand side throughout the match. The pro player can hit up to 50% more than that.

How this relates back to screenwriting is that, at first glance, the Black List writer doesn’t seem to be doing much different from the amateur writer. But if you look closer, their character work is just a little more thought out. Their structure is a little cleaner. Their dialogue is a little more thoughtful. Their scene work is a bit better. And when you add all those things up, the Black List script reads better than the amateur script.

Now, you may point out that the Black List scripts are hardly show-stoppers. I agree. To extend the metaphor, if a pro player ranked 90 in the world goes up against a pro player ranked 7 in the world, the lower ranked pro player isn’t going to look so great. In other words, very rarely will someone on the Black List write a better script than Quentin Tarantino or Aaron Sorkin. Those guys are in another bracket. But, that doesn’t change that fact that the low-ranked pro player is still better than the college player.

That’s a very long intro into today’s script but it’s something I’ve been thinking about for a while and I wanted to share it with you guys. Cause I know how frustrating it can be to read some of these Black List scripts and be confused. So, in a second I’ll tell you how you can elevate your writing up to Black List level.

Viva Mexico follows a 40-something sometimes-commercial actor named John who also happens to be a former superhero named Captain Bald Eagle. John’s agent calls him to tell him that he’s been hired by the governor of a small southern Mexican city to take care of a recent issue involving a local cartel (called “Cartel Cartel”).

John flies down to Mexico in his Captain Bald Eagle uniform and is told by Governor Pena about a dangerous man named Juan Rojo who has kidnapped five congressmen. He wants Captain Bald Eagle to take Juan down.

But as soon as John is out of the meeting, he’s kidnapped by a nasty looking tattooed fellow named Sordomudo. Sordomudo busses John to a warehouse, puts on a Mission Impossible mask of Juan Rojo, and proceeds to video tape a decapitation of John.

Well, an “almost” decapitation because a bunch of gnarly men break into the warehouse and kidnap John. John wakes up at the compound of the real Juan Rojo and learns that Sordomundo was working with the governor. Their plan was to stage a video murder of Captain Bald Eagle, making it look like he was killed by Juan Rojo, which would’ve given the government international approval to go scorched earth on Juan Rojo.

But, according to Juan Rojo, the government is the real cartel. Juan and his community are the good guys. And yes, they did kidnap those politicians. But only because they plan on exposing the government. Captain Bald Eagle decides to join Juan Rojo in this endeavor which gets complicated after Sordomundo kidnaps a young Mexican woman John has fallen in love with. Juan and John decide that this will end on Mexcian Independence Day. They are are going to battle Sordomundo’s cartel to the death. And they’re going to take back Mexico for the people in the process.

I could never grasp what this script was trying to do beginning with its concept. It’s a weird one. Bring in some over-the-hill American superhero to solve a Mexico-specific cartel problem?? It’s definitely not an idea that rolls off the proverbial high concept tongue. It takes a few run-throughs to make peace with it.

And there’s a ton going on here. It’s actually exploring some pretty deep ideas in regards to the troubles Mexico is facing. But, at times, it’s trying to tell that tale in a funny way. Captain Bald Eagle is supposed to be Bob Parr from The Incredibles, I think. A former great superhero who’s now over the hill and needs to find his chi again. But it was very poorly set up.

It wasn’t even clear, at the beginning, if John *was* a superhero or a guy wearing a suit pretending to be a superhero. And then when we do find out he’s a real superhero (he’s kind of a low-rent Captain America), we’re told that he only got half-a-dose of the super-serum. So he’s not a true superhero. And, also, I think his shield is the only thing that allows him to have his powers? It’s not well explained.

If I had to give the script a comp, I would say it’s similar to The Unbearable Weight of Massive Talent with Nic Cage. An American “superhero” gets chummy with a cartel boss. But that script was written with a level of assuredness that this script is missing. So, even though Viva Mexico was competently written, it’s misguided from the get-go.

Okay, back to our metaphor. How does a college player become a top 100 ranked pro player? Well, it’s not one fix. They work on EVERYTHING. They might realize that they’re falling backwards whenever they hit their backhand, which takes 15mph off the stroke. So they get to work with their coach, who feeds them thousands of backhands where they now practice stepping into the backhand. After several months, their backhand is a completely different stroke.

They may be doing something technically wrong on their serve that’s leaving mph’s on the table. It could be that they’re not tossing the ball forward enough or maybe they’re making contact with their body falling instead of pushing upward. These slight tweaks might add as much as 20 mph. Their footwork may be a little slow so they spend 30 minutes after every hitting session doing footwork drills. This allows them, in matches, to get to balls earlier, which means they’re prepared sooner, which makes the shot easier.

In other words, you’re making all of these small improvements that, when added together, up your total game play. So that’s all you should be doing in screenwriting. Identify your weaknesses and try to improve them.

Do you have enough conflict in your scenes? If not, write 100 practice scenes where all you focus on is adding conflict. Are your characters interesting or boring? If they’re boring, study the 30 most interesting characters in movie history, write down what makes them interesting, and then start incorporating some of those traits into your own characters. Do you know how to construct your 50 page second act to move quickly? If not, study pacing (adding goals with some sort of urgency attached).

The closest thing to a “skip the line” strategy in screenwriting is finding that elusive awesome concept. But minus that, it’s just hard work. It’s making all these little improvements in your “game.” Eventually, those improvements add up to an overall improvement that puts you on the Black List.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: “Sorta” doesn’t work in movies. “Sorta” superhero. “Sorta” drug-addict. “Sorta” selfish. “Sorta” villain. I’m sure you guys can come up with a few exceptions, but movies, by and large, work best when your characters have definitive traits. He’s a superhero. He’s a hardcore drug addict. He’s cripplingly selfish. He’s a deadly villain. Not only did the “sorta” superhero thing here make Captain Bald Eagle wishy-washy and, therefore, less compelling. It also made him confusing. I was trying to figure out, through the first half of the script, why he hadn’t done anything super.

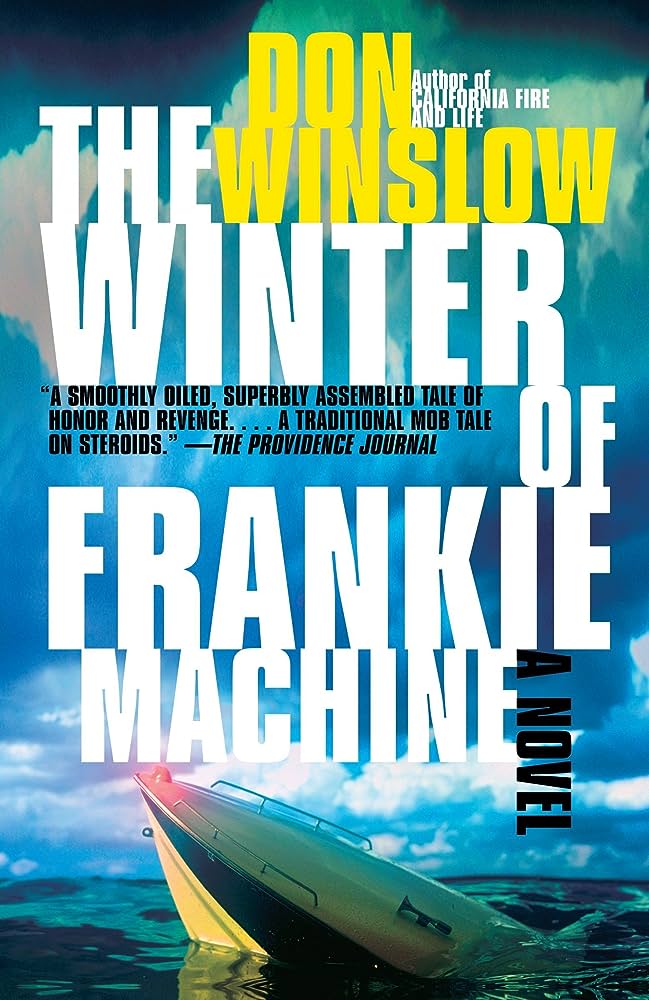

One of my favorite new writers, “The Bear’s” Christopher Storer, chooses his big “level-up” project, aka, his first feature film.

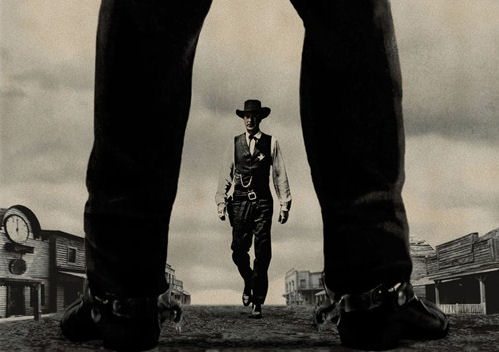

Genre: Crime

Premise: A retired mob enforcer living the breezy surf life in San Diego is targeted by an unknown entity who wants him dead at all costs. But if you come for the Machine, you better not miss.

About: This project has a long history. Robert DeNiro was attached. After that, Michael Mann was attached. More recently, Matthew McConaughey was flirting with the project. It was recently raised from the dead again when The Bear’s Christopher Storer came on board. Word on the street is that Storer will work from the Brian Koppelman & David Levien draft they wrote for Martin Scorsese.

Writer: Don Winslow

Details: 300 pages

As we make the inevitable segue from hyper-femininity to hyper-masculinity, I must concede that I’ve never been the biggest fan of mob movies and their over-the-top displays of machismo.

If somebody looks at you the wrong way in these films, you shoot him in the face and exclaim with a big throaty yell, “Badaboom badabing, baby!” then walk out and get your family promotion, which entails managing more strip clubs or something. I struggle to figure out the appeal of such stories.

The only mob movie I truly love is Goodfellas. I admire The Godfather but I’ve always thought it was a bit slow. Believe it or not, I’ve never even seen past the first episode of The Sopranos.

So when I heard that The Bear’s Christopher Storer was going to be doing a mob movie for his first feature, my heart sank a little. Not just because I don’t like the genre. But because nobody does anymore. They don’t put these donuts in the oven these days because the audience has shrank to the size of a donut hole .

But you know what? Sometimes, when you go into something with the lowest of expectations, that’s when you’re most likely to be rewarded.

60-something Frankie Machine runs a bait shop on the San Diego coast. For all intents and purposes, he’s happy living the retired life. The problem is that the life he’s retired from doesn’t allow for the typical retirement plan. Frankie used to be the fiercest hitman in the business. That’s where he got his nickname, “The Machine.”

One day, Frankie is visited by a couple of low-level mob dorks who tell him that he’s been asked by the guys back in Detroit to meet with a gangster named Vince on his boat. Frank does a little reconnaissance. It checks out. So he goes to meet with Vince, only to realize he’s been set up. A 400-pound man tries to decapitate him, but even a 65-year-old Machine is immune from decapitation and shoots both his attempted killer and Vince dead.

The mob, we learn from Frankie, is complicated. There are different factions (San Diego, Los Angeles, The Valley, Vegas, Detroit) that are all interconnected with each other. Which means Frankie can’t just walk away from the botched hit and sell bait again. He has to figure out who wanted him dead, why, and then kill all the parties that are on that “Frankie sleeps with the fishes” chain.

What follows is a very complicated investigation with well over three dozen characters, all of whom are related, in some capacity, to those five factions. Along the way, we delve into Frankie’s past and how he started in the industry, rose up, and eventually became the most feared hitman on the planet. Ultimately, Frankie learns that this goes higher up than the mob, where ‘honor among thieves,’ the only thing allowing him to stay alive, doesn’t apply.

This book was a great reminder of the power of scene-writing.

Because, as I was reading through the first 40 pages of Frankie Machine, I was on the fence about whether I was going to continue. It wasn’t bad. But it was all setup. It was all how Frankie’s job worked. His love of surfing. His complicated romantic relationships. His daughter getting into college.

I still think that even professional writers make the mistake of going on cruise control with this stuff. They think, “You owe me your attention,” as opposed to the proper way to think as a writer, which is, “It’s my job and my job solely to keep you entertained.”

In the end, all of this information Winslow provides us is crucial because when Frankie gets set up, we wouldn’t care if we didn’t feel like he was a real person. And everything Winslow did to this point turned Frankie into a real person in our eyes.

But there are ways to offer this information in a more entertaining manner. While you have the right to lay it all out like a list, it’s better to build scenes that are entertaining where the byproduct is the character’s life.

As an example, if you wanted to establish your character’s day, you might show them go to the ATM to get some money for that day’s activities. You can do that alone with no drama whatsoever. Or maybe some guy shows up and cuts in front of your protagonist. Says he’s in a hurry so he’s sorry, even though he’s not.

Now you’re showing us your hero’s daily activity but doing so with a little storyline. How your hero reacts to that situation will tell us a lot about him. And I guarantee it’ll be more entertaining than him grabbing 200 bucks out of the ATM and we’re off to the next scene.

Luckily, Winslow’s big inciting incident scene finally arrives. And that’s when Frankie gets set up. When he walks onto that boat and a 400-pound man appears behind him and throws a wire over his neck and starts pulling, while we hear the two young mobsters run away, signifying that Frankie’s been set up, we feel this immense anger towards those guys, as well as these two men in the boat who try to kill him.

There are few better scenarios for making a character likable than having someone try to hurt them. So despite my issues with the non-entertaining setup throughout the first 40 pages, I still felt connected to this character due to that work and was very angry when these two tried to kill him. From that point on, I noticed a huge shift in my investment in the story. I was now determined to see Frankie take down whoever did this.

Not long after that scene, we get one of the most intense scenes I’ve read in a couple of years. Frankie is a young buc mobster just starting out, and he gets tasked with driving home the wife of a mob boss.

Things get tricky when said mob boss’s overly sexual drunk wife starts putting the Missus Robinson moves on Frankie. When he rejects her, she tells him that if he doesn’t sleep with her, she’ll tell her husband that he tried to. It’s a devastating situation for Frankie because if he sleeps with her, there’s a good chance the mob boss will find out and he’ll be killed. And if he doesn’t, the wife will tell her husband he tried to and he’ll be killed.

If the scene only covered the resolution of that quagmire, it would’ve been great. But it gets even more intense when both the mobster husband shows up as well as a senior mobster who Missus Robinson was flirting with all night to piss her husband off, who now wants to close the deal, and he doesn’t care that her husband is in the way.

What follows is not a scene that you’ll ever see written in 2023 (this book was written in 2006), and left me with my jaw permanently extended.

Those two scenes being in such close proximity to one another built up so much good will in the writing, that I was all in. Even if the rest of the book never quite reached those heights, mainly because it spent too much time in the past (the past always pauses the more important present storyline that your readers are there for) and there were sooooo many characters that it was hard to keep up.

But, again, the power that those two scenes had over me kept me invested in what was going to happen to Frankie all on their own.

Scene-writing, everybody. If there’s one skill that will provide massive dividends for you in screenwriting, it’s scene-writing. If you learn the mechanisms for writing a great scene (three acts, goal, stakes, urgency, conflict, unexpected developments, with clever uses of suspense, anticipation and/or dramatic irony) you’re basically unstoppable. Cause you don’t even need to worry about the larger picture. You’ve become a master at hooking the reader in the present. This is what Tarantino is so good at.

It’ll be interesting to see how Storer simplifies this. Cause there’s no way he can keep all these characters and all these mob divisions. But I’ll be there for whatever he does.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: You should aim for 3 great scenes in your script. You know how the other day I was saying, try to make every scene at least an 8 out of 10. Well, three of those scenes should be 10 out of 10s. They’re the kind of scenes that you could imagine being talked about 30 years later. Coming up with great scenes is as hard as anything in screenwriting. But you should try. I’ll remember the Missus Robinson scene in Frankie Machine for the rest of my life. That’s the power that great scenes have over readers.

Also: Here are ten screenwriting lessons from The Bear!

Barbie has one of the worst messages I’ve ever seen in a mainstream film. And no, it’s not the message you think.

Genre: Fantasy/Toy

Premise: When Barbie learns that the person playing with her in the real world is having depressed thoughts, she travels there to try and sort it out, causing complete mayhem for the Mattel toy company.

About: Barbie just crossed a billion dollars at the box office and it doesn’t look to be slowing down! The phenomenon kept the film in first place against three heavy-hitting contenders this weekend. Yet in its third weekend, it still came out on top.

Writers: Greta Gerwig and Noah Baumbach

Details: 90 minutes

I don’t know why it’s taken me this long to see Barbie.

I’m not a Barbie hater.

I’m sure if I grew up as a little girl, I would’ve been yanking these dolls off the shelves.

I was just never convinced this movie was made for me.

I walked into the theater yesterday hoping I was wrong.

Let’s see what happened.

In case you haven’t seen the film, Barbie lives in Barbie Land, a place where all the Barbies are living their best life every day and all the Kens are cast off to the side, usually at the beach.

One day, Main Barbie (Margot Robbie), has her thoughts interrupted by death. Confused, she starts searching for the meaning of this unwelcome thought-intrusion. While that’s happening, we get to know Main Ken (Ryan Gosling), who’s only ever wanted to be with Barbie and, yet, Barbie enacted atomic-level friend-zone status upon him.

Barbie eventually figures out that whoever’s playing with her in the “real world” is the one having thoughts of death. So Barbie travels to the real world (with Ken, reluctantly), to clear all this up.

Once in the real world, she’s confused by the fact that women don’t rule, but rather men do. Consequently, Ken is the happiest person ever. He didn’t know there could be a world where men dominated.

So while Barbie tries to find this girl who’s playing with her, Ken heads back to Barbie Land, and turns it into a Ken-topia, instilling the rules he learned about dude-osity in the real world, which basically amounts to making horses a primary feature. That and there’s a lot more bro-time.

When Barbie finally comes back from her travels, she sees that the Kens have taken over. So she gets all the Barbies together, concocts a plan to have them all fake-cheat on their Ken boyfriends so that they’ll fight with each other. And while they’re busy doing that, the Barbies will re-institute the matriarchy. The End.

I’m going to be honest.

This movie has one of the worst messages I’ve ever seen in a mainstream movie before. Maybe the worst ever. And the idea people have of this being some fun happy film… I mean, if you have no concept of subtext then maybe. But, otherwise, you should be recognizing how terrible this movie’s message is.

But before we get to that, I actually liked a lot about this movie.

I absolutely loved Ryan Gosling. This is his most memorable role ever. It’s not close. He was hilarious. That image of him in the big fur coat throughout the final act is iconic. His musical number was awesome. I loved everything about Gosling in this.

I also liked Margot Robbie. They say the mark of a great performance is that you can’t imagine anybody else in the role. That is Margot Robbie in Barbie. I’d say that maybe – MAYBE – the only other person I could see pulling this off is a 28 year old Reese Witherspoon. But, other than her, Margot Robbie was it.

It says a lot that despite me hating the message of this movie, I still liked the primary character who delivered that message.

I liked Villain Ken (Simu Liu). That actor is really growing on me. He was the perfect foil for Main Ken.

I liked the concept of the film and found it all rather clever – this idea that you’re being played with by someone in the real world and their feelings can seep into you. And the only way to stop it is to go into the real world. And then you have the meta stuff with Mattel freaking out that one of their Barbies has gotten into the real world. All of that was fun. I’m a big fan of fish-out-of-water stories and I don’t think it’s a coincidence at all that the two biggest movies of the year (Barbie and Super-Mario) are both fish-out-of-water scenarios.

Greta Gerwig is now an official directing force. I admit that I previously saw her as an indie mumblecore vet who lucked into a Hollywood directing career. I did not pray at the alter of Lady Bird. But the vision of this movie is so strong and so distinct that I don’t think you can argue that Gerwig is anything other than a top-tier director in Hollywood.

Wow, Carson, you liked a bunch of stuff here. So you must have loved the movie!

No. I definitely did not.

The reason for this is that this movie hates people.

Something that I’ve despised over the the last five years is the way the media has worked so hard to divide us with these stories that pit one side against another.

In particular, ever since #metoo, there’s been this not-so-subtle campaign within the media to divide men and women. And, to a certain extent, I understand why this happens. Online media thrives on bold controversial takes. The most toxic divisive take is going to get the most clicks. And clicks equal money. I don’t like that the media stokes this division. But at least I understand it from a financial perspective.

The Barbie movie, however, doesn’t have to live by these rules. And yet it still chooses to. The message of this movie is, literally, men and women shouldn’t be together. We must always hold each other down.

That is literally what Barbie says at the end. Because men are in charge and keep women down in the real world, us ladies are going to be in charge and keep men down in the Barbie World.

Are we serious here????

This is what you’re teaching people!!!!!????

Some people are saying this movie is anti-men. I don’t think it’s anti-men. I think it’s anti-harmony. It does not want men and women to live in harmony with one another.

And the saddest thing about that is that Greta Gerwig and Noah Baumbach believe, from their privileged upper-crust educational ivory tower, that this is reality. That men and women hate each other and therefore should stay away from each other. When reality is the exact opposite. Go outside for an hour and talk to 20 men and 20 women and you’ll hear nothing but praise and love from each side about the other guaranteed.

If these two had their way, they would destroy that. They would get rid of that love. Because that love threatens their world view. If it turned out that men and women really do love each other, then there’s no cause left to fight for.

How out of touch are these two? Well, there’s this moment in the movie when Barbie first gets to the real world and construction workers start saying all these lurid things to her and I’m thinking, “Is it 1978? Who talks like this anymore? Better yet, when is the last year that a construction worker yelled out something sleazy to a woman? 1990 maybe???”

What reality are these two living in?

It’s such a sad point of view of the world.

One of the worst examples of this is the third act “Plan” to take back Barbie Land. On the men’s side, Gerwig and Baumbach have all the Kens serenade all the Barbies with Matchbox 20’s “Push,” a song whose lyrics are, “I want to push you around. Well I will. Well I will. I want to push you down. Well I will. Well I will. I want to take you for granted.”

Concurrently, the Barbies all agree to “cheat” on their Kens by going off and being with other Kens in front of them, so the Kens will get mad and start fighting each other.

These are the two behaviors Gerwig and Baumbach are choosing to highlight about men and women in the climax of their movie. What does that tell you about what they think about unity and relationships and togetherness and love? They hate it. Which is what makes this film so disgusting.

This was one of the most confusing moviegoing experiences I’ve ever had because, like I said, I loved so many things about the movie. And then this overbearing theme just destroys all that good will.

To a certain extent, I give these two credit because they did get a very dark message across in a giant Hollywood film. That’s hard to do. The studio system is built to be as inoffensive as possible. How they got WB and Mattel to buy into this message, I’m not sure. Maybe they were too dumb to realize it.

But that’s every indie writers’ dream, is to bring their dark indie-ness into the Hollywood machine because it’s so hard and Hollywood doesn’t ever let you.

And it’s paid off for them. The average moviegoer isn’t looking as deep as I am. They go to see the fun pretty colors, the beautiful Margot Robbie, and the funny Ryan Gosling, and they leave with a smile on their face. Which is probably the scariest thing of all. Is that they don’t realize that this dark toxic idea has now been injected into their brain. And that maybe, at some point in life, it starts manifesting itself.

Margot Robbie said it herself and I can’t agree with her more. “How did they let us make this movie?”

[ ] What the hell did I just watch?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the price of admission

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Don’t be afraid to inject darkness into your mainstream screenplay. Darkness is what gives stories depth. Even though I didn’t like this message here, the inclusion of death as well as the complexity of male-female dynamics makes a movie like this stick with you for a lot longer than other big Hollywood movies, for better or for worse. :)

What: August Logline Showdown

Deadline: Thursday, August 24th, 10pm Western Time

Send: Title, Genre, Logline

Where: carsonreeves3@gmail.com

We have a fresh Logline Showdown at the end of the month! For those who haven’t participated in a showdown yet, you send me your title, genre, and logline for a feature screenplay. I choose my favorite five loglines, which then compete on the site over the weekend with you, the readers, voting for your favorite entry. Whichever logline gets the most votes, I review the script the following Friday. I can’t wait to see what you guys come with this month!