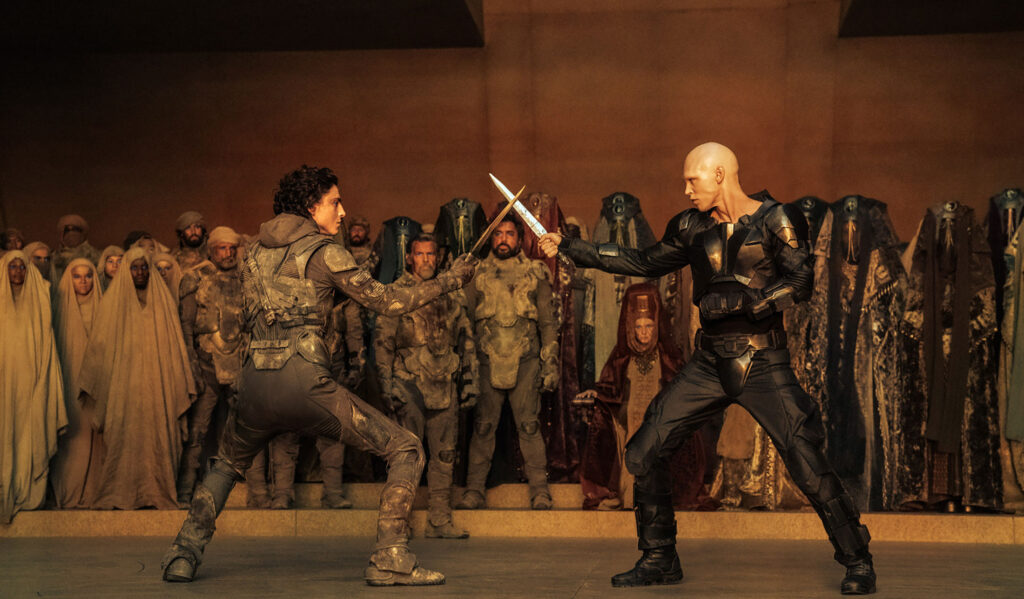

One of my weaknesses when it comes to watching movies is I put almost the entire onus of whether a movie works or not on the screenplay. So if the screenplay fails to deliver, I’m let down. Whereas, the average moviegoer and a lot of you guys are better at taking in the entire experience of the movie. You’re moved by the imagery, the acting, the sound, the music. That creates a stronger impression on you than me, which is why I feel that there’s a disconnect between myself and audiences when it comes to movies like Dune.

Dune 2 looks absolutely epic. The costumes alone are some of the best I’ve ever seen for a sci-fi movie. But that first screenplay, man…. That screenplay was so slooooooooooooooooooooooow. And I just can’t get over that. That and the fact that the movie is 90% world-building and 10% story. Maybe the first film was solely a setup so that this second film could fly. But Blade Runner 2049 (also directed by Villeneuve) had pacing issues as well. So my assumption was that I was going to get more of that in Villeneuve’s latest which is why I didn’t spend 20 bucks on it.

It’s weird because I run into people who absolutely loved the first movie. I remember I was walking on Larchmont (a fun little community-driven street in Los Angeles) and I saw this guy with the Dune book in his hand. I asked him if he’d seen the movie and he couldn’t stop raving about it. His love for it was so infectious I decided not to share how I thought the government should consider offering the film as the definitive solution for sleep apnea. But it was just a reminder that I’m seeing this film differently from everyone else. I mean, the movie has amazing critic and audience scores.

Despite my disinterest in the franchise, I’m thrilled that Dune 2 made 81.5 million dollars, doubling what the first film made on its inaugural weekend. What that means is we’ll get more adult sci-fi. And more adult sci-fi is better than whatever the heck the last five Marvel movies have been.

Those of you who didn’t watch Dune 2 probably stayed home and watched the other big epic release this weekend, Shogun, on FX. Just like Dune, the critics are infatuated with it. And, although it’s too early to rely on the audience scores, they seem to love it as well.

I read about one-third of the famous novel that the show is based on a decade ago. It’s one of those novels, ironically, like Dune. It’s world-building after world-building. There’s more building in this thing than Manhattan and Dubai combined. So it’s slow-going. What surprised me about the pilot episode was how quickly it brought me back to the novel. When a big scene popped up, it was as if I was right there in the book again. That’s how true it was to the novel.

The show also achieves something that’s critical to any show working – which is to get a lead actor that, whenever he’s onscreen, it’s impossible to look away. The second Cosmo Jarvis, who plays the lead character, John Blackthorne, showed up (he was being held in an underground prison with his fellow sailors) I was laser-focused on him. His eyes are mesmerizing. But he also has a really unique voice. Hey, maybe I’m better at focusing on the stuff outside screenwriting than I thought! Actually, hold tight, cause we’re going to get to the writing.

Here’s where I’m worried.

In a lot of ways, these new giant TV shows have become modern day “movies.” They may not have the presence of a feature film. But their longevity gives them a heavier weight when it’s all said and done. And therein lies the unique challenge of writing these series. They mimic movies with their sequential storytelling, but do so over a much longer period of time, which requires a much higher level of skill than the feature screenwriter.

I mean imagine writing an Avatar movie compared to writing eight seasons of Westworld. Which one do you think is harder?

Westworld by far. Which is why it fell apart and why a lot of these shows fall apart. They require a level of writing that only a few people in the world are capable of delivering. I don’t know a whole lot about Justin Marks, who created this series, but I do know that he wrote one of the worst screenplays of all time. That would be 2009’s Street Fighter: The Legend of Chun-Li.

This is where things get tricky because there’s this entire sub-level ecosystem when it comes to the screenwriting industry that makes it hard to know who’s responsible for what and how much they’re responsible. I’ll never forget when this producer who gave me too many extremely specific details for him to be lying, laid out why the credited screenwriter of Groundhog Day, Danny Rubin, was only responsible for the unreadable early drafts of the script, which is why you never heard from the guy again.

My point is, Justin Marks may not be responsible for how bad Chun-Li was. Maybe it was even worse and he made it “readable.” But even with that, his IMDB page doesn’t get my samurai sword extended, so to speak. He has The Jungle Book, Counterpart, and a ‘story by’ credit on Top Gun: Maverick. That last one is obviously huge. But Top Gun is a 180 degrees different universe than Shogun.

But the big thing that tweaked me was Marks hiring his wife, Rachel Kondo, to co-write and run the series. Rachel Kondo has zero writing credits. We all know how big nepotism is in this town. But this is one of the most outrageous examples of it I’ve ever seen. Would Marks have hired Kondo, someone with zero writing credits, to help him write a 300 million dollars show if she WASN’T his wife? I’ll let all of you guys answer that one. If you’re truly invested in creating the best series possible, you need people who have done this before.

Why am I bringing this up when the first episode was a solid 7 out of 10? Because, to me, this is why shows like this fall apart all the time. Cause the people writing them don’t have the developed skill to write a long-running complex series. Westworld is one of the best examples of this ever. And that had two pretty big names running it itself (ironically, another husband and wife team, Jonathan Nolan and Lisa Joy). I saw the wheels falling off the writing for that in the fifth episode. And every episode got worse from there. And that’s because it was this big giant story and the writers didn’t have the talent to visualize it and tell it.

This all stems from this new hybrid form of storytelling that streamers have created which is the “never-ending movie.” It used to be it didn’t matter that TV shows didn’t end because they were episodic. Each episode was contained to a murder or a group of people in an apartment yukking it up. But now, with the story continuing, you need to realllllllyyyyyy understand what you’re doing as a storyteller to make a story last 40-50 hours. The last show I can think of that achieved this was Breaking Bad. No show has done it since.

Maybe there’s a bit of a defense mechanism going on with me here. I’m saying this so that I won’t be hurt, once again, when Shogun gets sloppy in episode 5 and starts dovetailing. But it’s really a bigger issue. We’ve created this new TV genre that we don’t know how to wrangle. It’s the world’s biggest bucking bronco and no writer knows how to stay on it. Does that mean that it’s impossible to write these long-form movies? Should we even try since 95% of them fail?

The solution may be to do what Benny Safdie and Nathan Fielder did. Just write one contained season of a show (The Curse). It starts and finishes within eight hours. Even THAT’S really freaking hard to do, though. It’s harder than writing a traditional feature. But it’s certainly easier than writing a 50 hour movie when you’ve only got 8 hours of story in your head and a history of average creative choices on your IMDB page. Give me The Mare of Easttown. One great season and you’re out. Or The Bear. Keep your episodes short so you don’t have to tell as much story. And focus more on the characters than some giant plot the writer can’t keep up with.

What are your thoughts on Dune 2 and Shogun? Did either of them blow you away? If so, put me in my place!

Things get JUICY in this newsletter. I ordered a soap box specifically off Amazon so that I could get on top of it and give my thoughts on this new AI video nonsense. I officially announce the March Logline Showdown, which will make for the most fun showdown yet. I talk about a couple of development hell resuscitations, projects that Hollywood is finally making after 50 years. M. Night makes an appearance. Margot Robbie teams up with one of my favorite directors. Ooh, I share with you the THREE ways that scripts get purchased in 2024. You’re definitely going to want to read that. And we’ve got another short story success story, priming us for April’s Short Story Showdown on Scriptshadow.

If you didn’t receive the newsletter by 8pm Pacific Time, March 1, e-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com! I’ll personally send it to you and put you on the list.

The Scriptshadow March Newsletter is in your Inboxes! You can discuss the newsletter on the official post here!

A couple of weeks ago I sat down with screenwriter (and actor, and director) Leah McKendrick on a rainy LA morning at my favorite coffee spot, Sightglass Coffee, just off of LaBrea. It’s this big open space with a lot of creatives working there and I always enjoy the energy. If anyone wants to come by and say hi, I’m there three times a week. I’m usually working on an ipad with a white keyboard.

I wanted to catch up with Leah because she’s got a new romantic comedy called Scrambled, about a woman in her 30s who, because she doesn’t have a partner, has decided to freeze her eggs. It turns out to be an emotionally frustrating experience balanced out by a lot of humor, brought on by characters who seem utterly flummoxed by this choice of hers.

Our conversation was long and winding and while I originally planned on editing it down, I ultimately decided to keep it all because there’s some really great stuff here. Stuff about agents, dialogue, struggle, how to stay motivated, how to take your career into your own hands. I’m a huge fan of how Leah makes things happen in an industry that doesn’t want anything to happen. I’m going to pick things up BEFORE we started talking Scrambled. While waiting for Leah’s croissant (“I just got off the actress diet so I need carbs before we start.” “What’s the actress diet?” “When you don’t eat anything.”), Leah mentioned that she had developed a show at HBO before it fell through. So I asked her what it was like working with HBO…

LM: Yeah, I don’t know how it compares to other networks. I will say, all of the notes that I received were really smart. And really fair.

CR: Who was giving you notes from HBO? They assign you to a specific person there?

LH: Yes. Exactly. And that person’s team. But you have a point person you talk to. And that’s what’s really hard I think about making studio shows or studio films. There’s always another “box” higher up. Until it reaches the top. You’re never working with “the top.” So even if your point person absolutely loves what you guys are creating together, it still needs to work its way up the ladder. And if that top person changes for one of these 8 million reasons that top-people-changes happen, your project’s done. Because they don’t have any deep connections with your project. They weren’t a part of moulding it.

So that’s been something that’s been really hard for me is that I can be working with the studio very closely and they could be loving it and we could be really vibing but if their boss or their boss’s boss doesn’t get it? Like, “We gave it our best shot!” But I don’t view it that way. I view it like, “This is my blood sweat and tears. This is my baby.” But that’s just how this business works. Unless you’re getting to work with Nathan Kahane himself at Lionsgate. Like, it’s still got to make its way to Nathan and he’s still got to sign off on it. Thank god on Scrambled (laughs) Nathan signed off on it. There’s a good chance that Nathan could’ve been like, “No,” and Scrambled wouldn’t have been a Lionsgate movie. It still would’ve been made. But it wouldn’t have been a Lionsgate movie.

CR: So let’s talk about Scrambled because it feels like it’s the best example ever of “Write what you know.” Is that how this script came about? You thought, “I’m going through this. I need to write a script about it.”

LM: Yes. I was pissed off that I had to spend 14 grand (on freezing my eggs). So I was like, “I’ll use it as research and I’ll write a movie about it.” And I don’t even know how strong that urge was because more than anything I was like “I just have to get through this and freeze my eggs.” And I thought I wouldn’t write during that time because the pandemic was going on and that complicated things. But then out of curiosity, I started googling fertility films. And I realized there was no film about egg-freezing. It was always about the other methods. But those methods were about getting pregnant. And I was trying to do the opposite. I was trying *not* to get pregnant. Cause I didn’t have a guy. I was trying to buy more time. And that’s just so isolating and alienating for women. So I started writing down notes. And I just didn’t feel creative in that moment at all. And then as soon as I was done with my egg-freezing it was back to work. I had deadlines on other movies so I didn’t do anything with it until a year later after they killed Summer Loving (a Grease prequel Leah was working on) and they killed my directorial debut (another movie) and I was like, “I am not doing this anymore.” So I was like “I’m going to write my… give me three weeks, I will write my film about egg-freezing.”

CR: Is this something you ever discuss with your agent and management teams?

LM: (laughs) No. My team is the best. They know that I always go rogue.

CR: So then you guys never sit down together and they lay out a career game plan, such as, “Here’s what we think you should write? These types of movies are doing well so maybe you write one of them. This trend over here is hot so maybe write that?”

LM: Good question (thinks about it). No. In the beginning of my career they did. They tried to get me to chase moving targets. Nowadays no. And I would really advise writers away from that. “Knives Out did well so now go write a murder mystery.” Unless you LOVE murder mysteries, dope, go write it. But I know what I have, which is a pretty limited toolbox of things that I’m good at. So that’s what I write.

CR: You know your lane.

LM: Mm-hmm. I know my handful of lanes, I should say.

CR: Are you in the left lane or the right lane?

LM: Both at once, at all times.

Carson and Leah crack up.

LM: I’m in all the lanes at once which is what I should really say. But no, nowadays my team doesn’t try to get me to write in a genre or a specific type of film. They will say to me, “This project which you mentioned a year ago. What if we brought that one back?” Or, “You’re getting offered a lot of these types of genres. Do you want to do one of them?”

CR: So they’re coming to you with offers?

LM: Mm-hmm.

CR: And you consider that because it’s a paying job.

LM: Very rarely but at one point I did.

CR: Now, not so much?

LM: No, now (facetiously) I’m drunk with power. (Laughs). Now I don’t want to do anything that anybody wants me to do. Now I just want to build my own shit from the ground up and die on that hill. After they killed my TV show and they killed my two films, I just felt like I had done everything right. I’d played by the rules. I had been a good little soldier. And for what? You just killed everything.

CR: That seems to have had a big effect on you.

LM: A BIG effect on me. People feel like I should feel so much triumph because I made Scrambled and I do. But I’m so heartbroken. I will always be heartbroken because I worked so hard… here’s what I’m trying to explain because it’s not just my creativity. Because us artists have unlimited creativity. The more we sew, the more we reap. The more we create, the more we will create, the more that comes to us. BUT. That’s YEARS of my life. That’s what isn’t limitless. Is the days and the months and the years that I invested in building what they told me to. And then they didn’t even make it. So why would I continue to invest my one precious life into what you’re telling me to make if you’re not actually going to make it? So I was like, “The only way I have seen a way that has PROVEN ITSELF to be worthwhile and that has actually led to movies is when I was the one behind it. And I was the one who was saying this is when we’re shooting and this is how we’re going to get the money.

CR: So you wrote, starred, and directed in this movie.

LM: Yes.

CR: How did you do that? That’s hard.

LM: It was hard. But like I said, I was clean out of f$&%s. I was like, I’m not handing over my script. I’m not selling my script. Why would I go into development for three years? Regime change. More development. And another regime change. You kill it five years later. I don’t even own it anymore. It was an inefficient system that I could not subscribe to.

CR: One of the things that amateur screenwriters struggle with is a little bit of what you’re talking about but they feel even less power. They work on something and they don’t even know if an agent is going to pay them any attention. So that’s why a lot of them give up. They go through that process four times. Each time takes a year out of their life. They get rejected each time. And they finally say, “What’s the point?” But you seem immune to that. You continue to be more motivated than anyone I know.

LM: Yes.

CR: Where does that come from and how do you generate it?

LM: We’re going to get really deep for a second because it’s a sad answer. But that comes from the fact that my whole life I’ve felt behind. I have felt like I have failed. And it’s because I thought I was going to be Britney Spears at 16 years old. I was so frustrated as a kid. I had no interest in playing. I wanted to work. I don’t know where that comes from because my parents were not like, “You need to work.” But when you have had huge dreams your whole life and nothing has happened on the timeline that you wanted it to, it makes you quite desperate. It makes you feel like no one is getting it.

CR: I didn’t know you did singing.

LM: Oh yeah. I would make my own costumes and hire dancers with my allowance money when I was in high school.

CR: See, THAT. Right there. You went further than the average person would go. And this was technically before you were “behind” in life, right?

LM: Even then I felt behind. I wanted to be a Disney kid. I wanted to be Miley Cyrus and be on a Disney show. My parents were not into that. I was resentful. Cause I read about all these other kids whose parents would move with them to Hollywood and when I brought that up to my parents, they looked at me like… “We don’t even know what you’re talking about.”

Carson laughs.

CR: Let’s talk about Hollywood for a second and the pursuit of one’s dreams. Because there seems to be two ways to approach it. The first way is a negative one. You put your stuff out there and you think, “It’s probably going to be a no.” And the other way is positive. You put your stuff out there and, in spite of the no’s, you continue staying optimistic. You keep going. How do you keep that optimism having been through these numerous failures? How do you keep pushing no matter what?

LM: I think the thing that fed me and gave me that stamina all those years was that blind optimism of “I’m meant to be what I dream of becoming.“ Therefore, if I just reach the right people, they will see that I’m meant to do this and when that was proven wrong, it was a huge destruction of a worldview for me. Since then, what I think has happened, and this is a way I’ve evolved, and this is kind of sad also to be honest. Is that I’m not…….. good enough to be up there so I will have to make up for that in hard work. And that is why I decided that I had to write, and direct, and produce, and star, and finance (laughs). I will have to do EVERYTHING in order to make movies. I don’t believe anymore that I will reach the mountaintop. That I will reach the emperor and that he or she will tell me that I “made it.”

CR: (laughs) That moment never comes for anybody.

LM: (laughs) Exactly.

CR: Okay, so what I want to talk about is dialogue. You know I’m a fan of your dialogue. We talked about dialogue last time. This movie is very dialogue-driven. Have you learned anything new on the dialogue front since we last talked?

LM: Funny thing. Since we set up this interview, I’ve been waking up in a cold sweat in anticipation of this question. Cause I felt like last time I wasn’t prepared for it and I didn’t give a very good answer. That’s because a lot of it is instinctual to me.

CR: Yeah, that seems to be a common response from writers who are good at dialogue. They don’t have the best dialogue tips because they don’t have to think about it.

LM: Yeah.

CR: Well I have good news for you. I have it on good authority that if you give me a good answer, the Hollywood god will finally tell you you’ve made it.

LM: (laughs) I have one bit of advice I can give…

Quick Context Break: Both myself and Leah are big fans of the reality show 90 Day Fiancé. I have spared you from our conversation about the show in this interview. Don’t judge. Ryan Gosling is also a fan. Earlier, we were discussing one of the couples on the show. Their names are Geno and Jasmine. In the most recent episode, they got married. This is the context for Leah’s answer.

LM: On 90 Day Fiancé Geno and Jasmine were getting married and they were exchanging vows. So Geno’s giving his speech. His vows are what I would call “platitudinous.” They were enough for Jasmine and I love that. He’s not a writer by any means. And it was from the heart. But I forgot everything he said the minute he said it. Because everything that he said has been said a million times before. And I think that I am more interested in characters saying the wrong thing, or the semi-wrong thing, or going in a weird direction where you’re like, “ooh, this feels a little cringe.” And then coming around at the end and having one line that is so heartfelt. At least I will remember that moment and I will remember that writer who wrote that moment. Because if you’re going to sit up there and your vows are, “You complete me” and “I wasn’t myself until I met you” and “I’m going to love you forever.” No one remembers any of that.

So my boyfriend’s aunt was telling me a moment in my movie that really spoke to her and it’s this moment where a character is talking about their lost pregnancy. A miscarriage. And they had written a letter to their lost child. And they’re listing all these things that they wish they could’ve done together and one of them was, “I had all these plans to teach you how to not pluck your eyebrows, how to drive, and how to cook a chicken.” And she said the part about cooking a chicken just got her. And it’s like, “Why? Why is that?” Cause I don’t always know when I’m writing what’s going to hit, what is going to resonate. She said she couldn’t even explain what it was. Then we talked about it for a minute. And my thing was, as a Nicaraguan woman (my mom is from Nicaragua), it’s a big right of passage to pass on these skills. And one of those is roasting/cooking a chicken. And so I was just thinking about it in those terms. You know, when your kid graduates from high school and you’re sending them off to college, there are some skills that you want them to have. Right? You want them to know how to fold a fitted sheet. You want them to know how to cook at least something. Can you scramble an egg? So I was trying to come up with these basic go-tos of parenting. But the chicken really struck her, I think, because it’s visual. Because it’s specific. I think because it’s a rite of passage that only a mother would really know.

My larger point about dialogue is, the more general you get, the more forgettable it is. And the more specific you get, even if it’s the wrong thing, the more memorable it will be. And I would advise writers to use their own lives…. Like if you were going to teach your kid five things, what would those five things be? Get really specific. Because I promise you they wouldn’t be, “Oh, how to love.” (Laughs) You know? I don’t think that us as humans if we’re really in it or really honest, the more general it is, it means you’re not really trying. You’re not really thinking about it. It doesn’t matter how sweet your vows are. If they’re too general, they are in one ear and out the other.

CR: I like that answer because I deal with platitudes a lot and it’s a problem. More so in loglines lately. Wait, do you still have to write loglines as a working writer?

LM: I still write loglines. Yeah.

CR: Yeah, a big problem in the logline universe is general phrases that mean nothing. And for some reason, it’s hard for writers to understand that when I tell them not to do it. I don’t know why that is.

LM: You know what I think it is? And I mean no disrespect because I did it too. Sometimes we are *performing screenwriting.*

CR: What do you mean by that?

LM: You’ve seen so many movies your whole life. You’re like, “Oh, that’s what a movie is. That’s what movie dialogue is.” Which leads to imitation movie dialogue. As opposed to “I’m not imitating movies. I’m imitating real life.” And also, in some ways NOT imitating real life. Because real life can be quite boring. And like Geno saying his vows, real life vows are not always great. For some reason, I keep thinking of Jerry Maguire. That speech, “You complete me.” Yes you can say that that “hits” because… Tom Cruise. But I actually think it hits because he has not been that person for the entire film. The entire film he’s so self-involved. It’s all about him. It’s all about, “Who’s coming with me to help me because of who I’m supposed to be.”

CR: Jerry Maguire sounds like 16 year old you.

LM: (laughs) True. Yeah, he’s like who’s going to help me start my business, I’ve got to write this manifesto, I gotta get clients. Dorothy’s just on the sidelines. And there’s this big reversal in this final moment where he realizes I’m nothing without you. And they were able to encapsulate that moment through dialogue.

CR: Would you have written that line?

LM: (spends the longest time thinking about the question of any moment in the interview) I think… I think I would’ve written something along those lines. I don’t know if it would’ve been fucking epic.

Carson laughs.

LH: But I can feel in my heart as a screenwriter that that’s his journey. That his journey informed the line. And that’s why I get frustrated sometimes by studio notes is that, sometimes we’re so afraid of characters not being likable, that their arcs are (Leah visually mimics a flat line path with her hand) Wah-wahhh. And I’m like, “People will want to be on a ride and if somebody is… if you’re struggling to like them… that’s okay. As long as you give them that moment in the end. But I’m personally more comfortable having somebody be a little more self-involved, a little bit of a dick, a little selfish.

CR: What is your character in Scrambled like? Is she unlikable? What’s her flaw?

LM: No, I think people really like her. The flaw is, I would say, that there’s some arrested development there. She’s struggling to grow up.

CR: Now, you’re basing her on yourself, right? So you have to do some pretty intense self-reflection to write that.

LM: I mean, I think I’m still struggling to quote-unquote “grow up.” But I would point a finger at society telling me that growing up is being a mom. And I’m going, I don’t think that’s true. I think I’ve grown up in a lot of ways. And I am an adult in a lot of ways even though I don’t have a picket fence and a husband and 2.5 kids and an “acceptable” job. So yes, in some ways it’s her reckoning with society’s standards of what an adult woman should look like. But also the ways in which she herself has been infantilizing herself is a rebellion against that. And I think that’s totally me. I have a hard time with a lot of this stuff. I feel like I have worked my ass off and I have a career in the toughest industry in the world. Why isn’t that recognized as “adult?” Why isn’t that recognized as a huge triumph for me?

CR: Sounds pretty good to me.

LM: Well thank you. But you get it. Because you’re here. People who aren’t… have always been so curious about my love life. Always so worried about my age.

CR: What is that like for you? When you get that question? And are these moments in the movie?

LM: The whole movie is moments like that. I will tell you in one instance…I had just been hired for a big screenwriting job. I was very excited. It was early on in my writing career where I wasn’t getting offered big jobs and I had fought for this one. And I was telling a friend. I was so excited. I was feeling really good. And her question was, “Aren’t you worried about having kids cause you don’t have a boyfriend?” It felt so out of left field. And it kind of kept me up at night.

CR: What did that have to do with you getting the job?

LM: Excellent question. I think she may have been projecting some of her own fears on me. She was seeing me successful and wondering why she hadn’t been able to figure out that side of life yet. But I confronted her about it later and we worked it out.

CR: Is that in the movie?

LM: Not specifically but the whole movie is this specific conflict. How you shouldn’t measure a woman’s life achievements by these metrics. Husband. Baby. House. And when I did buy my house, it did feel like this moment where I was like, “Well I don’t have a husband. But I bought my house from this money that I made from my dreams. Every dollar that bought this house was from my acting and my writing. So fuck you. Cause I still got here. And I still have a house in the exact area that I wanted to get a house (in the Hollywood Hills) and it may just be alone but I’m not behind. And that was what was really hurtful. That everybody made me feel that I’d chosen my career over having a family and I had ruined my life because I had chosen my career. That’s what the film’s about.

CR: Random question. Was buying that house stressful?

LM: Super stressful.

CR: Could be a future screenplay. The struggles of buying a house.

LM: (laughs) It’s funny because when you start making money you become a bit existential about it. “What is this money I’m getting? What does it even mean?” But when you buy that house and you’re sitting in your chair looking out your window in the exact type of home you’ve always wanted in the exact area that you’ve always wanted, that’s when you realize what the money is for. That piece of mind and that safety. There’e something tangible I can point at. I had nothing when I moved here. My parents had cut me off because they said, “You have to do this on your own.” And now I have a house in the hills. And I achieved that by doing all the things that people told me not to do. So that’s my little arc.

CR: So when can we see Scrambled!

LM: It’s coming out March 1st on streaming! Apple, Amazon, and On Demand services. Oh and by the way, I just wanted to give a shout out to your site because last time I did an interview I was terrified to check the comments because I never check the comments cause they’re always mean. But the people on your site are so positive and supportive. It was really cool.

CR: Yeah, outside of a few outliers in the comments section, 99% of the people are very positive in their discussion about screenwriting.

LM: Oh, I wanted to say one more thing before we stop. We were talking earlier about screenwriters giving up. And whenever I hear that, it hurts my soul. Cause think of all the incredible scripts and stories that will never be written or made because of that. And regarding what I’m about to say, if this is not you and this is not in your heart, that’s fine, I understand that. But if you have this amazing story and nobody’s giving you the time of day, consider putting on that producer hat. Stop thinking that others passing on your screenplay is where it ends. I don’t care if you’ve written Citizen Kane. It doesn’t go anywhere without you. I’m of the Duplass brothers school of making movies. Which is, “How inexpensive can you make it?” “Is there a version you can do for 100 grand, 200 grand?” I know we would all love 5 million dollars to make our first movie. I know! But they’re not handing that shit out. I’m such a big believer that if you want to be making movies you have to be making movies.

So many people in this town don’t want to read your script. Like people send me their script and want me to read it – I DON’T EVEN READ. I’m trying to change that but we’re all busy, you know? It’s so hard to get people to read your script. But they *will* watch your movie. Making something small. Even if it’s a dope ass scene. Or even if it’s a teaser. I just feel like the thing that has done more for me in my career than anything else is making my own work. Taking my scripts and getting friends, raising a little bit of money, going to the festivals trying to turn it into something bigger, that has been my trajectory. And I know that it can be disguised by the fact that I’ve been writing studio films. And look, I’m grateful that I have a house like I talked about. But that didn’t get me Scrambled. The way that I got Scrambled is by saying I’m *not* doing that anymore. I am going to make this. I’m going to direct it. I’m going to star in it. I’m not taking no for an answer. And they try to dissuade you. A lot of companies offered me money if I wouldn’t act. Or I wouldn’t direct. They always do that. And it makes you feel sh&%$y. But my point is I wish that screenwriters also saw themselves as filmmakers, also saw themselves as producers. Because that will make all the difference in your life.

CR: Do you think you would be successful if you only wrote scripts to sell them?

LH: 100% no. 100,000% absolutely not. I think there are better writers who have smaller careers than me. The way that I got a screenwriting career was by making MFA (her first film about a campus rape). And I’ll be honest. I reread that script not that long ago and I was like, (laughs) “This is not good.” I thought it was the best shit ever when I wrote it. I thought I was Aaron Sorkin. I really did. But at the time it was the best that I could do. Truly. The beauty of it: it was a decent script, it was a better film. Because my director and main actress knocked it out of the park. And then it went to South by Southwest because South-by just f&%$ing gets it. And they can see… ideas. Even if they’re not fully formed. And it came out the week of the Weinstein scandal and the birth of #metoo. So there was some luck there.

But that happened and I had a screenwriting career. And then I was selling scripts right and left. And then I was getting called for adaptations. That would not have happened with the script alone. I’m telling you. The script was not that good. But the beauty of it is that I took my script and held it tight and I was like, “I’m muscling my way to the finish, eyes closed with or without any of you people.”

So I would just say, writers, I promise you, probably 90-95% of you are more talented than I am (laughs). But I’m very very very tenacious. And hard-working. And my secret to producing is just, I’m good at asking for things that I have no business asking for. I’m good at calling up everyone I know and going, “Have you ever thought of investing in film? Have you ever wanted to be in a movie? Can I use your house to shoot in? Can I use the campus to shoot in?” I’m good at that. I’m good at calling up SAG and saying, “This isn’t fair. You gotta let me star in my own film and not be creating all this red tape for me to rehearse. I’m good at calling everyone up and being like, “I need to get this done.” And the smaller the project, the more miracles will happen. That’s how it is. The bigger the project, the more bullshit will happen (laughs). The smaller and scrappier your film is, the more times you’ll have someone say, “Eh, all right, you can shoot in my backyard. All right, you can have free parking.” You know, I put every penny I had ever saved up in my life at the time into that film? 10,000 dollars. It was my hail mary. I didn’t have a plan B.

CR: Leah, you are the Katt Williams to my Shannon Sharpe. You held nothing back today. Thank you for coming out on this uncharacteristically rainy LA morning. Any last words?

LH: Go watch Scrambled!

Week 9 of the “2 Scripts in 2024” Challenge

Week 1 – Concept

Week 2 – Solidifying Your Concept

Week 3 – Building Your Characters

Week 4 – Outlining

Week 5 – The First 10 Pages

Week 6 – Inciting Incident

Week 7 – Turn Into 2nd Act

Week 8 – Fun and Games

Every Thursday, for the first six months of 2024, Scriptshadow is guiding you through the process of writing a screenplay. In June, you’ll be able to enter this screenplay in the Mega Screenplay Showdown. The best 10 loglines, then the first ten pages of the top five of those loglines, will be in play as they compete for the top prize.

Why is this such a great challenge? Because IT’S SO DARN EASY! What other screenwriting teacher out there asks for just 45 minutes a day? 45 minutes a day! And, at the end of this, you have a finished screenplay! Pretty sure there’s not a better deal on the internet.

But this week things get tough because page 45 is a deep crack in the screenplay’s crust. It is the official end of the “fun and games” section and the beginning of what, I call, “the real screenplay.” There is a rope bridge that takes you to the other side, aka the rest of the script. But it is so run-down that, any wrong move and you could plunge into the endless abyss between the two sides.

To understand this, you have to understand that the second act is an act that separates the professional screenwriter from the aspiring screenwriter. The professional screenwriter understands why the second act is there and what needs to be done during it. Whereas the aspiring screenwriter fakes the second act. They don’t understand what the directive is or how to navigate it. So they write a bunch of scenes that vaguely push the story, grasping at straws all the way until they get to the climax.

The reason screenplays fall apart here as opposed to immediately in the second act is because the “fun and games” section (first 12-15 pages of the second act that we discussed last week) provides them a grace period. The audience is so excited to be off on the adventure that they’re easily entertained. It’s hard to show up in Oz and not marvel at all of the wackiness surrounding us.

But once that excitement wears off, you actually have to entertain us. To do so, you have to understand what the second act is. The best way I’ve been able to define it is: It’s the “Conflict Act.” This is the act where your hero starts pursuing their goal (kill Thanos, find the Ark, build the atomic bomb, start a chocolate store, get through therapy a la Good Will Hunting) and encounters a lot of obstacles along the way.

You create obstacles not just for conflict but because you want your hero’s journey to be difficult. Nobody’s interested in an easy journey. They want it to be hard. When it’s hard, it creates drama. And it’s the drama that pulls us in. The second Willy Wonka shows up in Paris and announces he wants to buy a chocolate shop, the other three chocolatiers immediately conspire against him. They will provide a series of obstacles that Willy must overcome, starting with buying off the local police chief and telling him to arrest Willy at every turn.

That’s the general idea of what you want to do. But it doesn’t give us a blueprint we can follow this week. In order to do that, I need to tell you about the Sequence Approach. The idea with the Sequence Approach is that a movie has 3 acts and, within those acts, a series of sequences. In the first act, there are two sequences, about 12-15 pages long each. In the second act, there are four sequences, 12-15 pages long. And in the third act, there are two sequences, 12-15 pages long. That’s 8 sequences in total.

Because we’re on pages 40-50 this week, we’ve already written our first three sequences. We are now on the fourth sequence. All a sequence is, is its own little mini-movie. The reason the approach is valuable is because it takes the giant chasm of space known as the second act and it turns it into smaller, more manageable, chunks of real estate that provide a clear start and end point.

All you have to do in a sequence is create a little “mini-movie” that has its own beginning, middle, and end, that lasts around 12-15 pages.

This is something I worked extensively with Elad on in the tennis loop script we worked on, “Court 17,” which made the Black List last year (the script follows a character who gets stuck in a loop playing the same U.S. Open first round match over and over again getting destroyed by a much better player – he thinks that the only way to get out of the loop is to win the match).

Before we had sequences on that script, we were lost. A loop movie is particularly susceptible to structural issues because you’re writing the same day over and over again. How do you make each scene feel different if you’re stuck on the same court in the same match all the time?

You make it different with sequences! We broke the script down into eight sequences. Sequence 1 is the character’s day before the loop, going into and losing the match. Sequence 2 was the first day in the loop, the confusion and fear that went along with what had happened to him. Sequence 3 had him start to formulate a plan to get out of the loop by using the repetition of the match and a series of different strategies to beat his opponent. After endless failed attempts at winning, Sequence 4 had him giving up and, instead, focusing on winning his estranged wife back (who lived in the city). Sequence 5, he placed his focus on his opponent – studying him and meeting with him in an attempt to learn what made him tick in order to gain an edge in the match. And so on and so forth.

Once you have a sequence, you have a game plan. And, as long as you’re writing via the tenets of good storytelling, you’ll be in good shape: At the beginning of each sequence, give your character a goal. Have them go after that goal. Have them encounter obstacles that they must overcome. And, because it’s early in the movie, have them fail, fail, fail, and fail again. Of course they’ll have little victories along the way. But failure should dominate the second act.

I had never put as much emphasis on the sequence approach as I did in the writing of Court 17 and I learned something in the process. A sequence doesn’t have to be self-contained. In other words, if you have a subplot with Character Y that doesn’t perfectly fit the theme of the sequence, you can still include a scene with that character. Just as you can cut to other subplots with other characters during a sequence. As long as the majority of the sequence is your hero pushing towards the goal of that sequence, the sequence will work.

But if you’re just using your second act to randomly jump from this scene to that thread to that subplot back to this scene and you don’t have a plan for it all, that’s when second acts get messy. That’s when it starts to feel like the writer doesn’t know what they’re doing. And it’s not even that we, the reader, will think, “This writer clearly doesn’t know what they’re doing.” But we will think, “I’m bored.” That’s all it takes for a reader to give up on you. “I’m bored.” The Sequence Approach is the best approach I’ve found for preventing boredom in the second act.

If you’re confused about page starting points for the Sequence Approach, here’s what they look like…

100 page script

1-12 First Sequence

13-25 – Second Sequence

26-38 – Third Sequence

39-50 – Fourth Sequence <— you are here

51-62 – Fifth Sequence

63-75 – Sixth Sequence

76-88 – Seventh Sequence

89-100 – Eighth Sequence

110 page script

1-13 First Sequence

14-27 – Second Sequence

28-42 – Third Sequence

43-55 – Fourth Sequence <— you are here

56-70 – Fifth Sequence

71-84 – Sixth Sequence

85-98- Seventh Sequence

99-110 – Eighth Sequence

120 page script

1-15 First Sequence

16-30 – Second Sequence

31-45 – Third Sequence

46-60 – Fourth Sequence <— you are here

61-75 – Fifth Sequence

76-90 – Sixth Sequence

91-105- Seventh Sequence

106-120 – Eighth Sequence

Your assignment this week…

Friday = write 1 scene (last scene in the fun-and-games section)

Saturday = write 1 scene (Construct a sequence for this section)

Sunday = write 1 scene (moving towards the sequence goal)

Monday = write 1 scene (moving towards the sequence goal)

Tuesday = write 1 scene (possibly a subplot scene)

Wednesday = go back and correct any issues with your five scenes

Thursday = go back and correct any issues with your five scenes

Genre: Zombie Thriller

Premise: When a zombie disaster overtakes the city out of nowhere, a family is trapped in their high-rise Miami hotel. With danger closing in fast, they’re left with only one way to go: Up.

About: This script finished with 11 votes on last year’s Black List. The writer, Aaron Sala, wrote a spec sale script called “Beast” years ago that I really liked. But it’s not anywhere online cause it was a newsletter review. Yes, Beast (The lone survivor of a plane crash finds her way to a small island where a monstrous beast lives and becomes intent on killing her) is similar to that other script that got made about a beast on an island. But this was the good version. It wasn’t the bad one that got made.

Writer: Aaron W. Sala

Details: 106 pages

Yesterday’s post had more plot in it than Arlington National Cemetery. Yes, I just made a cemetery plot joke. Welcome to Wednesday on Scriptshadow.

Wait, what is that you have under you, Carson? Is that a… soap box? Indeed it is fellow readers. And it’s here to allow me to say a little something about the nature of screenwriting. Make sure your tray tables are up and your belongings are stashed away because I’m mixing metaphors and this landing is going to get bumpy.

You see, the scripts that do best on the spec market – and when I say spec market, I’m not talking about selling so much as I am getting managers and agents or producers interested in you – are the ones that have easy-to-follow plots. Like today’s script! You read today’s logline and you say, “I understand that. That sounds fun. I’m in.” It’s very simple.

If you want to add complexity, do so on the character end. Make your characters weird or unconventional or wild or deep or have an odd relationship with another character.

If you still have a TON of plot, consider writing a TV show. Cause a TV show will allow you to expand that plot out over 10 to 20 to even 40 hours. That way, all those plot points won’t be crammed up against each other. You might only deal with one of them per episode.

After yesterday’s disaster of over-information, I need some script detox. I need something I can easily follow. I need something to thrill my a-s-s off. Will The Last Tower be that thing? Grab your hotel key cards and hold the elevator for me so we can find out!

Harold, Angela, and daughter Zelda (13) are flying into Miami for a rare vacation. It’s rare because Mommy Angela is always working. Her job is that of a corporate fixer. When the excrement hits the fan, she’s the one who stays calm, grabs a spoon and some paper towels, and meticulously picks said excrement out of the fan.

The fam gets to their snazzy Die Hard-like hotel, which is a whopping 70 stories, and no sooner do they settle in than they see a giant cruise ship crash into the beach right in front of their hotel. Not long after, people with yellow-green gunk on their faces stumble out of the cruise ship and, news flash, they ain’t walking normally.

Barely any time passes before giant swarms of people are attacking everyone in Miami. Angela and Zelda, who are down by the pool, recognize that they need to get away from here ASAP. Before they know it, a swarm of crazed people are attacking others in the lobby. The two run for the nearest elevator and get in it after only a few stories.

They maneuver off the stuck elevator by manually opening the doors and get up a few floors where they find some people giving shelter in their room. Once inside, Angela realizes the truth she cannot yet tell her daughter – that her father is likely dead.

Staying cool as a cucumber per her training, Angela starts figuring out her next move. She realizes that downstairs = death and upstairs = a chance at life. She has no idea if help is ever coming. She just knows that the further she and her daughter are from the insanity of downstairs, the better.

They’re able to get a room a few floors higher with another group waiting things out. But when the zombie hoard start banging on that door, they need to find another way up. The only other way up is outside. Xavier, a bellhop, is three stories up and they’re able to communicate with him the old tied-together-sheets-rope move. One by one, they have to climb up the makeshift rope.

The next challenge is the fact that the upper floors of the building, where the private residences are, can only be accessed via a special elevator with a special key. Xavier has to find that key so they can create some real distance between themselves and the zombie hoard. Naturally, things go wrong. And it becomes clear that, no matter what they do, they’re probably not getting out of this alive.

Unpopular opinion: Starting a script in Antarctica always works.

Try it. Start your script in Antarctica and I guarantee it begins better than if you didn’t start in Antarctica. In The Last Tower, a bunch of richies took a cruise to Antarctica and a kid ate some tainted snow. Snow laced with an alien microbe!!!! Hence the craziness. Let this be a lesson to kids everywhere. Stay away from alien microbe-laced Antarctic snow. I feel like this should be obvious but, apparently, idiot children are still making the mistake.

The Last Tower is one of those concepts that’s going to work no matter what. No matter how loose and soggy the execution is. It’s the special power that a good concept gives you. It creates an imaginative state in the reader where, even when the writing stinks, they can IMAGINE the good version of that scene. Or that another writer is going to come in and fix the scene once it’s officially slated for production.

The Last Tower only messes up in a couple of places. The first is that the set pieces are too expected. A stopped elevator scene where they open the door and they’re split between two floors and people have to jump out hoping to god that the elevator doesn’t decide to start up again all of a sudden, slicing your body in half.

Remember, you always want to envision the “average” screenwriter writing your script and ask yourself, “Would Average Screenwriter write this set piece?” If Average Screenwriter would, that’s a good indication you need to do better. Average Screenwriter would definitely write a stopped elevator split between two floors escape scene. So it’s not the best way to go.

The sheet-rope one is better because, even though it’s familiar, it creates a genuinely tension-filled sequence. But it still felt like a top-tier screenwriter – one of these studs hired by the studios to come in and knock out a final better draft 3 weeks before shooting – would come up with something more original than this. Or at least add something new to the set piece to make it unique.

Since we dinged our Logline Showdown winner on the site a few weeks ago with his island zombies, how do I feel about the zombies in The Last Tower? Well, the zombies were not original. They’re basically the same type of zombies used in 28 Hours Later. They seem to be stronger, which allows them to knock down doors that protect our heroes. So that was good. They also swarm together, which was kind of a twist. But they weren’t special.

However, it didn’t matter that much because the ascent up the hotel to escape them created a “combo” strange attractor. Sure, I would’ve been mad about the familiar zombies if our characters were running around on the streets of Miami. But because we’re doing something more specific and interesting – painstakingly moving up this skyscraper – it does feel different from your average zombie movie.

The bigger mistake the writer made was not executing this in real-time. That was a really poor creative choice. When we’re at the midpoint and, already, 24 hours has passed?… that’s screenwriting malpractice right there.

Think about it. What is your script’s most valuable asset? It’s these relentless zombies that don’t stop coming up after you. If they stop? If our protagonists have time to catch their breath? You’ve just killed ALL THE MOMENTUM in your story. You can’t do that, man. This concept is screaming for a real-time story, giving you a capital “U” (for Urgency) in your GSU.

Despite this, the concept’s fun-factor overrides the negatives. This is definitely a movie. And, unlike yesterday’s script, it’s actually enjoyable to read.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: A “fear flaw” doesn’t work when the situation overwhelms that flaw. In this movie, Zelda is afraid of heights. It’s established heavily throughout the first act. Now, on a basic writing level, this seems like a good idea. You have characters who are going to be up high. Why not give one of them a fear of heights? Well, here’s the thing. If this movie was about a serial killer chasing Zelda and her mom through the building, placing Zelda in a situation where she would need to traverse over something when she was way up in the air, that would work well. But when you have a zombie swarm that has just killed 3 million people, who the f$%# cares about your fear of heights? You’ve got way bigger fish to fry. Nobody’s looking at the 20-story high metal beam they have to tightrope-walk across to get to safety, then looking back at the vicious zombie hoard who you just saw rip up 70 people in less than 30 seconds and saying, “You know what? Fear of heights wins today. I’d rather just let the zombies turn me into cornmeal mush.”