Genre: TV – 1 hour drama

Premise: Two dads in Suffolk County engage in an intense feud that bubbles over into their innocent childrens’ baseball league.

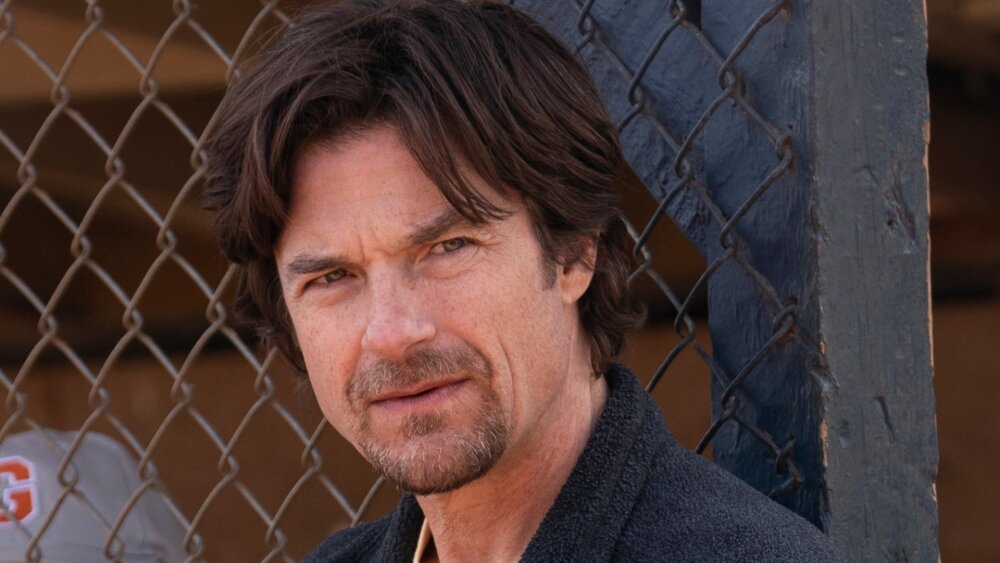

About: A huge article purchase from over on Esquire (article has a paywall unfortunately). Jason Bateman and Netflix continue their love affair as the streamer paid big bucks to bring their Ozark pal back into its arms (Netflix beat out SEVEN other rabid suitors). Bateman will direct and star in the show about two little league fathers who get into a very intense rivalry that involves criminal activity. They’re going to have to figure out a better title though because when I first saw this, I thought it was a story about a Cinderella-type ball that dads attended.

Writer: David Gauvey Herbert

Details: About 6000 words

One of the best ways to sell anything in this business is to write a story that’s similar to a recent hit.

This actually used to be harder because the strategy was built almost entirely around giant movie successes. So if Armageddon made a billion dollars its opening weekend, you’d be competing against thousands of other screenwriters with your “Armageddon adjacent” spec script. A giant Astroid threatens the world? Well, what about a giant tidal wave!?

But these days, there are a lot more opportunities because success has become more relative and diversified. A crafty screenwriter looks for smaller “mini-successes” and pitches projects similar to them.

Case in point, today’s sale. The Daddy Ball project was clearly pitching itself as “The next Beef.” And boy is that a powerful pitch when all of the elements align. You have to be in the minds of these buyers. They’re terrified of buying something that sucks. So any little image you can put in their mind that indicates success – like a recently popular show – helps out.

With that said, I’ve found that you have to be careful not to jump onto mega hits. I experienced this myself a couple years ago while trying to pitch a really good racing pilot with a writer. We pitched it as a Succession set in the south. What I didn’t realize was that, literally, EVERYONE was pitching “Succession set in the [blank].” And when that happens, the pitch goes right through one ear and out the other.

This pitch was perfect because Beef was a hit but a low-key hit. Not everyone saw it. And not everyone who did see it, liked it. However, the people who did like it, loved it. And, so, when you pitched “Beef set in the world of little league baseball,” your competition was small and the people who loved Beef were DEFINITELY going to request the script.

Back in the late 2000s, in Suffolk County, Bobby Sanfilippo was excited to get his 10 year old son into the local little league scene, which was becoming a big deal. To get on one of these traveling teams, you had to fork up a couple grand. But Bobby was more than happy to, since his son (who can’t be named) loved baseball.

Bobby’s son joined a team called the Inferno and that’s when Bobby first met John Reardon, a sort of daddy psychopath. John’s son Jack would come onto the team and be an instant star. He had all the makings of a kid who could go pro one day. Much better than Bobby’s son, who was just a good player who loved baseball.

When the team started to get really good, parents wanted to get rid of the weak players. John seemed to spearhead the movement to get rid of people like Bobby’s son. So Bobby, who was doing well financially, took his son and STARTED HIS OWN TEAM, naming it, “Vengeance.”

Not long after, the two teams would play, Jack’s team would win, and John would scream some really terrible things at Bobby’s son. When the Vengeance coaches called him out on it, John pulled out a bat and came at them. In the end, everybody calmed down, but this daddy rivalry had gone up a notch.

One day John started getting all these text messages sent from an anonymous phone that contained pictures of his family doing everyday activities accompanied with threats that John was “done.”

Several months later, during a Vengeance game, the police showed up, arrested Bobby for the messages, and made him do the perp walk of shame in front of his team. Although Bobby denied sending the messages, the damage had been done. The team was never the same since many of the parents believed Bobby was guilty.

Bobby had always contended that John was friends with the local police chief and the two had constructed this hit job together. A couple years later, this gained more credence when that police chief was taken down by the FBI for running his precinct like the KGB. In the end, both fathers still think they were right in all the things they did. And both still hate each other.

I’m not sure what to make of these non-traditional magazine article sales. You guys remember that Monopoly one from a couple of years ago? The one that Matt and Ben bought? That thing died in a blaze of glory quicker than you could say, “How bout them apples.”

I understand why this sold. In addition to the “Beef” connection, you’ve got that all important conceptual irony to hang your baseball cap on. It’s because this is set in the world of little league baseball that it has a juicier taste. You shouldn’t be sending life-threatening messages over junior sporting events.

But I was hoping for a lot more chaos. I actually thought, when I read about this in the trades, that it was going to end in murder. That’s the expectation with these true stories now. So, when you don’t get all the way there, the audience is like, “That’s it??”

At the very least, I was hoping for an ongoing rivalry between the two teams. But there were only two games and both of them were uneventful except for Jack striking out Bobby’s son and John bringing out a bat afterwards, a bat he didn’t even use.

That’s what this story felt like to me. A whole lot of blue baseballs. It was always on the brink of something gnarly happening but nothing gnarly ever happened. In fact, any sort of issue between the two dads was an adjacent issue. When Bobby’s son left the Inferno, for example, it wasn’t John who kicked him off. It’s not even clear if John had any opinion on getting Bobby’s son off the team.

And then there’s this big thread about how John was distantly related to the local police chief, which is why the two had worked together to illegally take down Bobby. But that’s never proven. The evidence actually leans towards the two never having spoken to each other in their lives.

Stories work best when the attacks ARE DIRECT. Not adjacent. In Beef, it wasn’t that Danny *might have* kidnapped Amy’s daughter. He *DID* kidnap her daughter.

Unfortunately, this feels like a writer who thought there was more to this story than there was, spent a couple of years and a lot of interviews on it only to find out, in the end, it was really a rather tame story. He then did his best to imply a lot of bad things happened.

To be fair, it worked out. It’s being turned into a TV series. But for this to work, they’re going to have to add A LOT MORE to the story. This needs to be completely fictional if it’s going to be as entertaining as Beef. If they filmed this as is, people are going to leave this series saying, “Did you really just make a TV show about two people who yelled at each other a couple of times?”

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: In a script like this, you need at last one “Holy S—t” moment. If you don’t have a “Holy S—t” moment in a movie or show about a bitter feud, then the feud you’re writing about isn’t nasty enough. Beef has that shocking traumatic ending. There’s also the house burning down. There’s Danny secretly sabotaging his brother’s future. There isn’t a single “Holy S—t” moment in Daddy Ball.

This weekend, I found myself checking the box office numbers for the weekend and noticing that the two top movies (Elemental and Spider-Verse) were holdovers, and that neither cracked 20 million. The big new release, No Hard Feelings, sputtered to the finish line with 15 million dollars.

We are in the middle of summer! Summer is when everyone’s supposed to go to the movies! And not a single film made 20 million bucks? What’s going on here??

When I fell in love with movies, box office was everything.

Because box office was the unequivocal deciding factor on whether a movie mattered or not.

Some of the most exciting moments for a movie geek like myself were when a film would come out of nowhere and do these amazing things at the box office that had never been done before.

For example, I remember how The Sixth Sense made 26 million dollars its opening weekend. And then it made 25 million its second weekend. That had NEVER happened. Not for a movie that had already gone wide. A 1% drop? It was unheard of. Three weeks later, it actually made MORE money that weekend than the previous one.

Then you had the opening weekend record-setters. The Phantom Menace opening to 65 million. Harry Potter opening to 90 million. Spider-Man opening to 115 million. Dead Man’s Chest opening to 135 million. The Dark Knight opening to 160 million!

There was excitement in the air whenever a big movie opened. Everyone talked about how much it could possibly make.

But these days, the numbers don’t seem to matter to people anymore. I don’t say that in a sad way. I’ve just noticed that people don’t talk about box office like they used to.

Consider Avatar 2. The film made 2.3 billion dollars at the box office. That’s the third most money a movie has ever made. Have you heard anyone touting that number? Have you heard anyone care about it? “Hey! Did you see Avatar 2 crossed 2 billion?!” Nobody’s said that to me. The trades felt like they had a gun to their head every time they reported about the film’s box office success.

So, what’s causing this change? Where is this apathy coming from?

The most obvious reason is the pandemic. Going to the movies was a habit people had. When you take that habit away for two years, it makes people evaluate whether that habit was valuable to them. Somewhere between 20-30% of the people who had that habit realized it wasn’t very valuable. And now they’re not going to movies anymore.

Rise of streamers – I’m not one of these people who think that being able to watch a movie or a new show at home is automatically better than being able to watch a movie at the theater. Because a big reason you go to the theater is to get out of the house. It’s cheap entertainment. And it’s fun to meet a friend or to go on a date and watch a movie together. With that said, streamers have given us SO MUCH MORE content that theatrical movies face more competition than they ever have before.

Also, streamers re-introduced a notion that had been absent from the industry for 40 years – no box office reporting. When a movie came out on streaming, you literally had no idea how many people had seen it. I remember when I Care A Lot came out. That movie got people talking. But we still had no idea, relatively speaking, how many people cared. Was it a 20 million dollar opening level of interest or a 50 million dollar opening level of interest? After we got 30+ streaming releases without that box office answer, we started to get used to the idea that box office didn’t matter all that much.

Next we have the politicization of movies. Mainstream films have more politicized themes than at any other time in history and it’s definitely hurting the box office. If there’s even a whiff of a movie promoting some political angle that conservatives or liberals don’t like, you’ve lost half your audience right there. It’s put moviegoers on edge and made them less trusting. Anything that gives people pause about going to the movies is going to eat into the box office. Which makes you wonder why they’re doing it.

The King of The Box Office has already happened – Avengers Endgame ruined everything. The movie made 350 million dollars its opening weekend. Nobody’s going to beat that. One of the things that audiences used to get excited about was, “Will this movie beat The Dark Knight?” Or, “Will this movie beat The Force Awakens?” Avengers Endgame is Wilt Chamberlin’s 100 point game. It ended the discussion. Which takes a lot of the fun out of the box office. If we’ve already hit our limit, it implies that we’re not growing anymore.

The younger generation doesn’t care – The GenZ’ers don’t get excited about this stuff. They’re more interested in how many views a tiktok video got. Or how many subs a content creator has. Box office isn’t on their list. Also, since this generation is growing up on streaming, their world of content is more immediate, and less about going out and seeing a film. Especially because if you go out and see a film, you risk getting triggered on the way there. I kid. But seriously, content on devices is more important to this generation than content on giant screens.

Finally, movies are no longer our zeitgeist moments – Back in the day, if a big movie came out and everyone was seeing it, you felt like you needed to see it too so you were in the know, so you were a part of the cool club. Movies aren’t like that anymore. The best example of this is the fact that we don’t have people quoting movies anymore. Everybody in the world knew the line “I’ll be back,” after The Terminator. Does anybody know one memorable line from last summer’s biggest movie, Top Gun? They’re more likely to know Paul Rudd’s line from his Hot Ones interview (“Look at us”).

This is because interest has been specialized. Instead of us all liking one big thing, our interest is divided into 20 smaller more specialized things. I love The Bear. But I just tried to have a conversation about it with my neighbor and they thought I was talking about a traveling circus. “No, it’s a show about a fast food restaurant in Chicago.” “I’m confused. When does the bear come in exactly?”

This used to be the reason why everyone would watch the same things. Cause they all interacted with each other and wanted common ground to talk about. But the internet and, more specifically, social media, changed that. If your neighbor or chem class partner didn’t watch The Bear, no problem. You can go online and talk to your pal, Choi, from Hong Kong, who loves The Bear so much he’s redecorated his place to look like the inside of Carmy’s apartment.

So what does it all mean? Is this a bad thing?

Sort of. Yeah.

In a way, the industry set themselves up for this. They’re the ones that celebrated the numbers. They’re the ones that touted from the rooftops that a Hollywood film had made 350 million dollars in a single weekend.

So now when Transformers Battle of the Armadillos makes 60 million dollars its opening weekend, you’ve conditioned the masses not to care about that. It’s literally one-sixth of what Avengers made. Why would I watch that film? Or Fast X at 67 million. Or No Time to Die at 55 million. Even when The Batman came out and made 134 million, I remember thinking, “Is that good for a Batman movie? Is it bad?” I didn’t know!

But the discussion is broader than that. Because I don’t think people care even when a movie does make a lot of money. The discussion is less about the money and more about the movie. When Top Gun became such a big hit, I didn’t hear anyone discuss how much money it was making. I heard people talking about how fun it was. How it was the perfect summer movie. But nobody was like, “Top Gun just passed 400 million!”

Which may be the silver lining here. Maybe now that we don’t have box office chains wrapped around our wrists and ankles, we can just appreciate that a movie is good. I’m fine with that. Box office has been a camouflage for bad movies for too long. Doing away with that unnecessary distraction allows us to see more clearly. I think I’m going to like a post box office Hollywood.

Every second-to-last Friday of the month, I will post the best five loglines submitted to me. You, the readers of the site, will vote for your favorite in the comments section. I then review the script of the logline that received the most votes the following Friday.

If you didn’t enter this month’s showdown, don’t worry! We do this every month. And next month, we’re having a special showdown JUST FOR PILOTS. I’ve gotten a ton of e-mails asking me why I don’t give pilot writers their time in the sun. Well, now their time has come. The deadline for Pilot Logline Showdown is Thursday, July 20th, 10pm Pacific Time. All I need is your title, genre, and logline. Send all submissions to carsonreeves3@gmail.com.

If you’re one of the many writers who feel helpless when it comes to loglines, I offer logline consultations. They’re cheap – just $25. E-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com if you’re interested.

I’m adding a little surprise this showdown since there are a full two months before the next feature logline competition. We’ve got SEVEN loglines to choose from. Oh yeah, baby!

Voting ends Sunday night, 11:59pm Pacific Time!

Title: Bubblehead Saves the Day

Genre: Teen Comedy

Logline: When two high school seniors discover a robot from outer space, they ignore its warning of an imminent alien invasion and reprogram it to help them score with chicks!

Title: Fragments

Genre: Mystery & Suspense / Thriller

Logline: A blacklisted nurse is approached by a detective with a unique job offer: become the caretaker for an acquitted murderer who may be faking his Alzheimer’s diagnosis.

Title: DEADLY FORCE

Genre: True-life crime drama/thriller

Logline: The true story of Jim Simone, one of the most decorated and reviled cops in the nation, a real-life Dirty Harry and Serpico, touted as a hero and a serial killer, he waged a deadly one-man war against criminals, corrupt cops, and the press, meting out his own brand of justice no matter what it cost him or his family.

Title: The Man Who Came From The River

Genre: Sci-fi / Period / Thriller

Logline: When his time machine malfunctions, a black man from a post apocalyptic future must team up with a young Confederate soldier to find his son in Civil War era Virginia.

Title: ALIMONY

Genre: Romantic-Comedy

Logline: When a founder of a dating app realizes her deadbeat husband’s alimony payments are bleeding her dry, she embarks on a mission to find him a new wife before her company goes public.

Title: The King of Ghosts

Genre: Drama

Logline: When a Haitian fencing master is reunited with his estranged daughter, he must decide between pursuing a new life with her, or remaining in a violent world of underground machete fighting with the orphan boy he’s caring for.

Title: Death’s Jaws At Her Back

Genre: Action/Horror

Logline: An ex-soldier is forced to confront her traumatic past when she becomes hunted by the product of a decades old Nazi experiment — an indestructible monster known as the Überkrieger.

24 hours left to get your June Logline Showdown loglines in (10pm Pacific, Thursday night)! Send your title, genre, and logline to carsonreeves3@gmail.com! Best five loglines will duke it out this weekend. Winner gets a review!

A couple of days ago I engaged in an activity I detest, which was to defiantly write off something I didn’t like. I just had to let the world know, in comment-form, that I hated “Joan is Awful.”

Is it possible, even once in your life, Carson, to keep your opinion to yourself? I guess not.

I watched half the episode and I was so put off by its annoying repetitive nature, that I accompanied my power-off of Netflix with a giant grunt. “What a waste of time,” I said, before posting my “Joan is Awful is awful” comment on Scriptshadow.

But the next night, something compelled me to finish it. And by the time I got done with those last 25 minutes, I’d changed my mind. I liked Joan is Awful quite a bit.

What changed?

I’ll answer that question in a second. Because the thing that changed my mind is a screenwriting mega-tool if you know how to use it. The problem is that it’s the hardest screenwriting tool of all to use.

I’m talking about… THEME.

Theme has always been weird. It’s like UFOs. They’re right up there in the sky but you can never quite see them. Theme is always blurry.

If you don’t believe me, google your favorite movie and ask, “What’s the theme of this movie?” I looked up Toy Story for example. I got five different themes spat back at me! Loyalty was one. The bond between kids and their toys was another. Learning to let go was another. The evils of jealousy. Self-acceptance was one.

If it’s that difficult to agree on a movie’s theme, then how effective of a tool is it?

I’m reminded of an article I wrote a couple years ago about White Lotus, specifically its theme of how the rich exploit the poor. This was what Mike White himself, the creator of White Lotus, in an interview, said was his theme. And yet I still had people in the comments telling me I didn’t “get” the show cause I got the theme wrong. It was, rather, about racism. Or the cluelessness of the 1%. Or the eradication of the Polynesian population.

That’s my issue with theme. Is that if you ask five people what the theme of a movie is, you get five different answers. And if theme is that loosey-goosey, can it really be quantified and taught?

Getting back to Joan is Awful, the episode is about an unhappy woman named Joan who works at a tech company, who, one day, comes home to watch Netflix with her boring boyfriend, only to find a new show called “Joan is Awful.” The show stars Selma Hayek, and Selma’s hair looks exactly like Joan’s.

Curious, they play the show. And a scene starts playing that is the exact same thing that happened to Joan earlier that day at work. As the episode continues, more scenes from Joan’s real life impossibly play. It becomes clear that, somehow, the show is a shot-for-shot recreation of Joan’s life, as it’s happening, including private jabs at her boyfriend, who breaks up with Joan even before finishing episode 2.

What follows is a rather convoluted series of events where Joan seeks out Selma Hayek (this is where I originally gave up on the show), and the two learn that AI is creating these episodes, using the digital likenesses of Selma and others. They then agree that they must destroy the supercomputer that’s creating these shows.

Enter Netflix’s CEO, who’s similar to the Architect (Matrix reference). She explains to Joan why they’re doing this. Joan’s show is a test-run. Netflix’s goal is to create real-life direct content for each and every subscriber on the streamer. Everybody will soon have their own tailored “Joan is Awful” show to watch.

Something about this explanation hit me. We are all so desperate for content. We want more more more. Despite there literally being tens of thousands of shows on demand, we’re still not happy. The logical endpoint for this is an AI supercomputer that can create endless shows catered for every individual on-the-fly. We’ll never run out of content.

This insatiable appetite for content cannot end well. And what the show is really saying is, let’s stop before it gets that far. Let’s go outside for once instead of binging The Bear season 2 (which I plan to do this weekend). The message (the theme), in that sense, is to live life, not content.

That’s when I realized why Black Mirror is so popular. Black Mirror shouldn’t be popular at all in this day and age. It’s not a continuous storyline. It’s not mega-IP like the Avengers or Star Wars. It doesn’t get to cheat and bring back characters the audience already likes. It has to start from scratch every time. And yet it still remains relevant. It still remains good. How does it do that?

In my review of “Match Cut” on Tuesday, I pointed out that you have to give your script a soul for it to resonate with people. Ashley chimed in in the comments with this observation: “I think if it feels like a soul is missing in a movie, it’s often because it’s missing a theme.” And that was an ah-ha moment for me.

That’s what Black Mirror does so well. It makes sure that every episode has a powerful theme. And that theme is what provides the episode with a soul. So when you watch a Black Mirror episode, whether you like it or not, you feel like you watched something that’s hit you on a deeper level.

I still don’t know the secret to coming up with a theme that everybody who watches a movie agrees on is *the* theme. Even a brief google search for Joan Is Awful’s theme gave me two themes that did not conclude what I just concluded. But I know that if you try to include a theme in your work, it has a much better chance of resonating with people. Look no further than Black Mirror’s sustained success as proof of that.

You’ve got 48 hours to get your loglines in for June Logline Showdown! Details below.

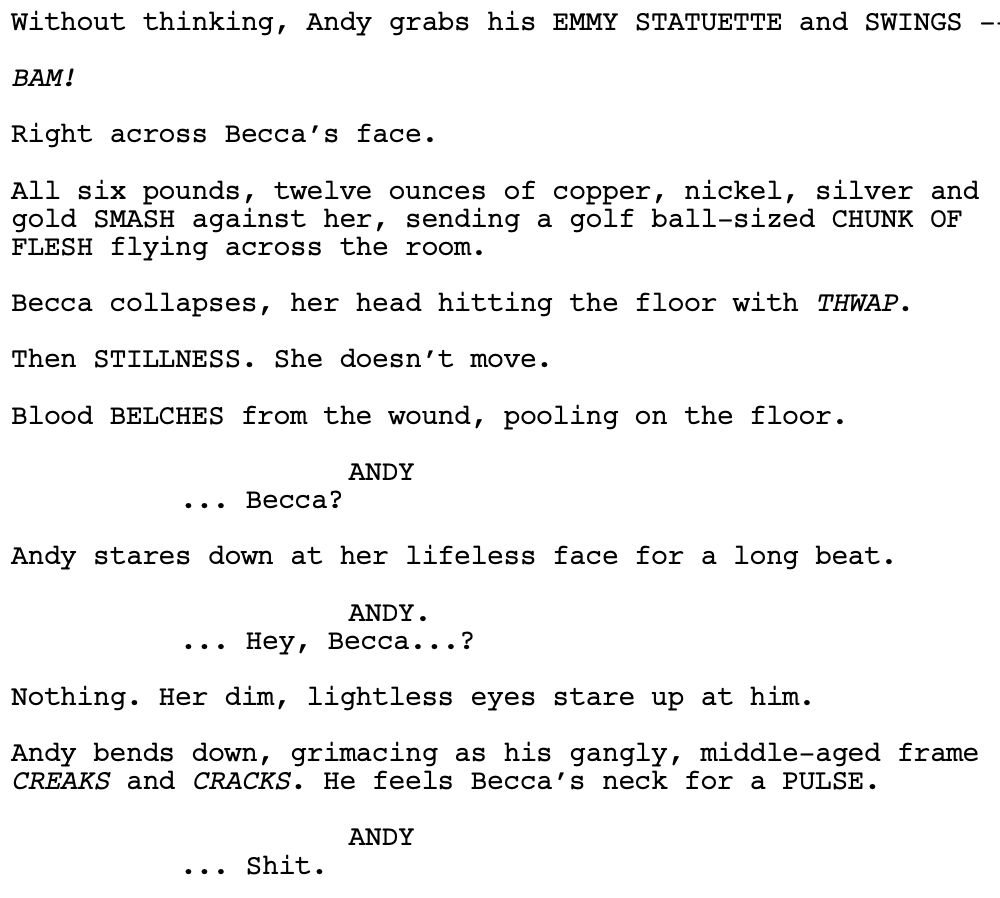

Genre: Drama

Premise: A schlubby, long-suffering late night comedy writer’s simmering anger and jealousy begin to boil over into madness as he suspects that his telegenic A-list boss is trying to replace him.

About: To get you guys excited about this Friday’s Logline Showdown, I’m reviewing May’s runner-up logline, the script I actually thought had the best chance at being really good. But I sensed it wouldn’t win just because it’s such a quiet concept. Yet another reminder to keep the reader in mind when choosing what concept to write. The more read requests you get, the more shots you get get at the winning combo.

Writer: Danny Albie

Details: 104 pages

Once again, this is a reminder that June Logline Showdown is this Friday. Deadline is THURSDAY! So get those loglines in!

When: June 23rd

Deadline: Thursday, June 22nd, 10pm Pacific Time

Where: e-mail all submissions to carsonreeves3@gmail.com

What: include title, genre, and logline

Hader for Andy?

Hader for Andy?

Onto our review!

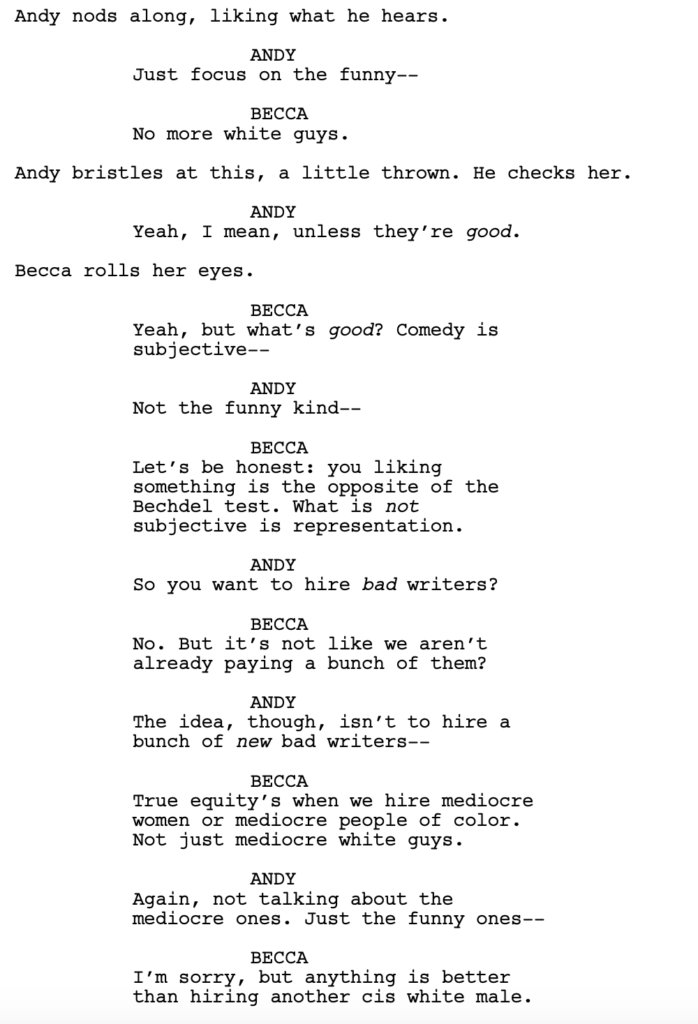

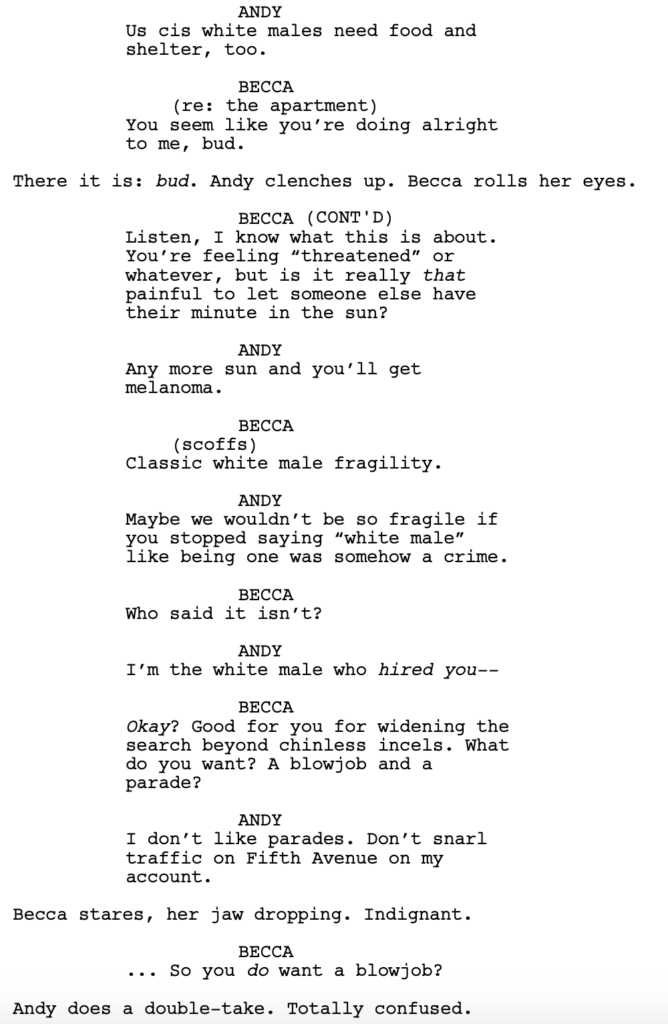

Andy Letts is a gangly 46 year old divorcee who’s the head writer on an aging late night talk show headed by the beloved Jack Rafferty. Andy’s life amounts to trying to write edgy jokes for Jack, getting turned down, replacing them with safe jokes that Jack wants, and watching as Jack gets all the credit.

Andy doesn’t do much otherwise. He doesn’t date. He masturbates to humiliation porn. He goes to therapy. He’s basically on autopilot. The only other activity he has is following this one girl on Twitter named Becca who occasionally writes funny tweets.

One day, Andy decides it would be a good idea to hire Becca. Especially because his entire writing staff is made up of straight white men. Jack, along with the show’s showrunner, are not happy about this new addition, especially because Becca wants to write more edgy left-leaning political humor. She’s more into “clapter” than “laughter.”

Becca eventually bullies her way into a segment on the show that does really well and that begins her meteoric rise. Within a month she’s the co-head writer on the show. More and more of Andy’s jokes are now being overlooked. It’s only a matter of time before she takes over his job completely.

Then, one night, Andy and Becca decide to get drinks. (Spoilers follow) The drinks go well enough that Andy invites her back to his place. They then get into a heated conversation about diversity that takes an unexpected turn into Becca threatening to falsely accuse Andy of sexual assault. The two get into a brief scuffle that ends with Becca dead.

Andy gets rid of the body, goes back to work, and hopes that everyone will just forget about Becca. And, for the most part, they do. But it turns out Andy’s not finished yet. The Becca escapade gave him a taste for blood, and a taste for finally getting that recognition he so rightly deserves after all these years.

The Head Writer has one of the most charged scenes I’ve read all year. It’s a scene that I’ll never forget.

But, on the whole, the script is a frustrating read for several reasons. So let’s talk about it.

The biggest problem here is that the story doesn’t have an engine underneath it. It’s one of those scripts where life is just happening. I understand that this is a character piece. But even character pieces need that engine pushing the story forward. We have to feel like we’re going somewhere.

After finishing the first act, I still didn’t know what this story was. Andy hires Becca but I didn’t know why. Andy’s problems at work are so vaguely conveyed that I wasn’t sure what the problem was that needed to be fixed.

About 70 pages into the script, Andy explains to someone, “My boss likes my writing but doesn’t like me.” And I thought, “Why didn’t I know that on page 20? Why am I only learning that now?” That’s how vague the first act was. It didn’t do a good job establishing the relationships, what was specifically wrong with those relationships, what was wrong with work, and why Andy needed to solve it by hiring Becca.

When Andy hires Becca, his reasoning seems to be a sprinkling of several things. The other writers don’t work hard enough. They need more representation on staff. Andy wants a younger voice to make Jack look hipper. Andy needs someone to help him with his duties. If you have a bunch of reasons, you don’t have any reasons.

For movies, you need one big reason so the audience is clear on why “the big thing” (in this case, Becca’s hiring) needs to happen.

In “Blackberry,” they need to hire Jim because they don’t have a shark. They have a bunch of geeks who are great at building phones but who don’t have any idea how to run a business.

Once Becca comes in, the script makes another curious choice. Becca insists on making more liberal jokes. Everybody on staff is afraid of this because of the repercussions. Hold on here. Unless this movie is set in an alternate universe, I’m pretty sure that the jokes you can’t tell these days on late-night television are conservative-leaning jokes. So that didn’t ring true at all.

We then go back to our engine-free narrative. Outside of Becca’s popularity rising, it’s not clear where the plot is headed or why we should still be watching. I still don’t entirely understand why Becca was hired. I don’t have a good grip on Andy’s situation with Jack. Jack kind of likes him but kind of doesn’t? It’s confusing. And now we’ve completely taken a left turn by turning the movie into a “late night talk show needs to be more woke” narrative, which comes out of nowhere. It was never established before Andy hired Becca that the show only told conservative jokes.

So all these things led to a very mushy narrative, and a narrative that didn’t have much push behind it. We don’t know where we’re going.

But then we get the Andy and Becca “date” scene.

One of the strategies to really get your reader invested is to write stories and scenes that rile them up. The things that Becca says and does in this scene – I got so angry! To the point where I was not unhappy when she met her demise.

More importantly, after forcing myself through the 60 pages that preceded this scene, only to be on the edge of my seat for six straight pages, I realized: This scene IS THE MOVIE.

But, unfortunately, everything around this scene, starting with page 1 and ending with page 105, needs to mostly be rewritten.

For starters, we need a stronger impetus for hiring Becca. It can’t just be because Andy thinks it maybe sorta might help. Somebody needs to come in and force them to do it. Or they were exposed on CNN for being the last writer’s room of all men. Something like that.

And then everything with Becca’s storyline needs to move faster. We can’t laze around. Create time goals. Maybe we establish that the Emmy nominations are announced a month from now and Becca is determined to get the show nominated. Something where we have a goal and we feel like time is of the essence.

Then, I think the Becca death needs to happen on page 45. Not page 60. You can’t be lazy with plot points in character pieces. It’s too risky cause the slower story is more at risk of getting boring. From there, maybe Andy finds her joke notebook. And so Andy starts using her jokes and he finally starts getting all the credit and acclaim he’s wanted. Meanwhile, the police are closing in on finding who killed Becca. And you can still do this thing where he starts offing other people on the writing team.

You do that, you’ve got a movie. Right now, you’ve got a meditation on what it’s like to be a head writer who nobody respects. That’s fine to explore that. But you need a plot surrounding it.

Script Link: The Head Writer

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: If you’re trying too hard to impress the reader, the line is going to feel off. Like this line, “Andy watches Shepherd cut a GIANT PIECE OF ICE CREAM CAKE. It’s so big, feet amputate themselves looking at it.” It took me several reads to realize this was a diabetes joke. It’s just too clever by half. The reader resents writers who are desperate to impress them. Just tell the story. That’s what we like.