After seeing John Wick 4, I started thinking about set pieces a lot. What makes a good set piece? What makes a bad set piece? What makes a great set piece! Set pieces are a big part of writing screenplays, especially if you’re writing big budget stuff. And they aren’t something you can wing on the spot. They’re their own unique skill.

Set pieces got their name from sequences that were so big, production needed to build an entire “set” for them. That’s why it’s called a “set” piece. But, as film has progressed, it’s ironically become more synonymous with big action scenes, which might take a sequence through many different areas, such as a car chase. So I’ll use “set piece” and “action scene” interchangeably.

My interest in set pieces was further bumped up by a recent script consultation I did for a superhero script where the writer’s primary request was to help him improve his action scenes. Having just seen John Wick 4, I felt like my head was in the right place for this. Even though I’ve written articles on set pieces before, it’s easy to forget some of this stuff. Being able to contrast some of the best action scenes in the business (John Wick) with an amateur screenplay, drives home for me the major differences between the two.

There is a caveat to this, though, which leads to the first mistake writers make when writing action scenes: Action scenes work better on screen than they do on the page. For example, John Wick 4 has this big flashy action sequence where John Wick fights an overweight boss guy in a nightclub. I have no doubt that, on the page, this scene reads boring. You’re basically writing, “He punches,” “He kicks,” “He dodges,” “He falls,” over and over again. But in the film? It’s a really fun scene. Mainly because the overweight boss guy is so fun.

But as I was saying, an inexperienced writer watches this John Wick scene and they don’t see much ingenuity there. Therefore, they don’t think they have to do anything special when they write their own action scene. Which results in them writing a boring action scene.

Therefore, the first rule of writing a great set piece is…

REQUIREMENT 1 – ORIGINALITY

You should be looking for a way to make your action scene unique somehow. The reason you don’t often see this is that it’s hard. You’re going up against millions of action scenes. It takes some real thought to come up with a fresh angle on one. But if you’re just going to give us another garden variety fight or garden variety car chase or garden variety heist, chances are you’re boring the reader.

Movie that represents this: Captain America: Civil War’s airport fight is a good example of how making one change in a major category, location, can create a totally unique scenario. We’d never seen a superhero fight before in this kind of location. They’re usually in the middle of New York or at the top of a building or in some lair or on some spaceship. With just a little more thought, you can come up with a place where we’ve never seen an action scene in that genre before.

REQUIREMENT 2 – AN EXTENSION OF YOUR UNIQUE CONCEPT

This is one I harp on the most on the site. No matter how much I do, though, it’s something I’m seeing less and less of every year. Which is a crime. Because it’s the thing that can really supercharge your set piece. And that is: give us an action scene that could only happen in your movie. Let’s say you’ve got a group of characters who are planning to rob a bank. Could that action scene happen in other movies? Yes! It can! Well then you are not writing an action scene that is a direct extension of your unique concept. The guy who’s been the master at this all these years has been Spielberg. He understands this law better than anyone and it’s not even close.

Movie that represents this: The opening of Raiders of the Lost Ark. Is that opening sequence appearing in any other movie? No. Because it was so specific to Raiders’ concept.

REQUIREMENT 3 – GOAL

Let’s move on to basics here. Having a strong character goal isn’t as sexy as an original action scene or an action scene that’s an extension of your concept. But action scenes are best when they have direction and purpose. That’s what a goal does. And the way to approach it is to think of your action sequence as a mini-movie. It needs to have a goal. That goal does not have to be fancy. It just has to be clear to the viewer. If your hero picks a fight with another character, we need to know the goal behind why he’s chosen to do so. Or else we’re going to be confused as to why the fight needs to happen. Also take note that it isn’t always the hero who has the goal. Sometimes it’s the villain who has it.

Movie that represents this: Spider Man: No Way Home – That flashy early scene where Spider-Man is on the bridge with all the stopped traffic and Dr. Octopus, who’s just emerged from another dimension, arrives and tries to kill him. Dr. Octopus’s goal is pretty clear in this scene: kill Spider-Man.

REQUIREMENT 4 – STAKES

We know here at Scriptshadow that if there’s a goal, stakes aren’t far behind. “Stakes” just means: THE SCENE HAS TO MATTER. There has to be some real consequences involved if things go wrong. And there has to be some clear upside to things going right. If a set piece feels boring despite it being original and an extension of your concept, the problem is probably there are little-to-no stakes in the sequence. If your hero is planning to rob a bank for 10 million bucks yet he already has 100 million bucks back at his house, why would we care that he’s obtaining 10 million more? You must provide us with the highest level of stakes you can on that particular set piece.

Movie that represents this: For this one, I’m going to use a negative example: NOPE. The final sequence in NOPE has our heroes trying to get a UFO on film. But what was the exact benefit of this? What were the stakes? The stated reason is that they were hoping to sell it for a lot of money. But there was zero clarification on if they’d be able to. Then they were going to use that money to, I think, save the farm. Although that wasn’t set up well either. So you have this gigantic set piece climax that contains average stakes at best. That’s how much stakes can affect a set piece. If they’re even a little bit soft, we’re not going to care what happens.

REQUIREMENT 5 – URGENCY

This starting to sound familiar? Goal. Stakes. And now Urgency. The reason these are necessary in the same way that GSU is necessary for your movie is that action sequences are like little movies. So it makes sense that you’d build them the same way you would your larger story, with a beginning, middle, and end. This one is self explanatory and you see it all the time near the end of movies. In that big climax, time is always running out. Urgency adds so much tension to a sequence that you’d be silly not to include it.

Movie that represents this: One of the most famous examples of this is the Dark Knight scene where Batman is told that Rachel is across town about to be blown up. So he has to race there and save her. Complicating things is that the Joker gives him two locations. So he doesn’t even know if he’s racing to the right one.

REQUIREMENT 6 – SIMPLICITY

This is easily the most overlooked element of writing a good action scene and it’s one amateur writers, in particular, screw up. You want to create a SIMPLE ACTION SEQUENCE where the goal, the rules, AND THE GEOGRAPHY (!!!) are easy to understand. Cause if they’re not, we’re going to be lost. If you’ve ever watched the ending of one of the recent Marvel movies where a million different things are going on at once and you have no idea what the rules of the sequence are supposed to be, you know what I’m talking about. There’s a cave and aliens and zombies and a land war and a sea war and, at some point, our hero has to zipline between buildings. Do you honestly think readers are going to be able to follow that? Give me simplicity on an action sequence every day of the week and twice on Friday. Need I remind you that The Matrix, considered one of the best sci-fi moves ever, has its climax take place in a hallway where one man fights three other men. As simple as an action scene can get.

Movie that represents this: Shang-Chi. The fight on the out-of-control bus. Note how easy those two things are to understand as a reader. A runaway bus – we immediately get it. A fight on that bus – we immediately get it. Why do you think they built their entire marketing campaign around that scene and not around the climax which had weird dragons and a million things going on? Because the bus set piece was freaking clear and easy to understand!

And there you have it. The six ways to write a great action sequence, aka, “set piece.” I know I called these “requirements” but do you need to include every one of these every time you write an action sequence? No. But your goal should be to include as many as possible. Cause I can guarantee you, the less of these you’re using, the worse your set pieces are. I’ll go one step further. If you can integrate these six rules into your set pieces consistently, you will write better action sequences than 75% of professional writers working today. I know this because I’ve watched too many movies where the writers have NO IDEA how to write a compelling set piece. As a result, their action scenes are exceedingly forgettable. Now that you’ve read this article, you will never have that problem.

SCRIPT CONSULTATION DISCOUNT 100! – I’m giving out a couple of discounted screenplay consultations. If you’re interested, e-mail me with the subject line, “100,” and I’ll take $100 off my regular feature script or pilot script rate. If you’ve never had notes from a professional, take advantage of this! I can help you identify and fix things in your writing that would otherwise take you years to learn on your own. Not to mention, I’ll elevate your current script. So if you want to get a consult, e-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com. I do features, pilots, first acts, short films, loglines, whatever you need!

Has the exceptional Sheridan written yet another great TV show?

Genre: TV 1 Hour Drama

Premise: Tommy works as a “fixer” for the oil companies in booming West Texas, where there’s a new problem gumming up the pipelines every day.

About: Taylor Sheridan is back with yet ANOTHER show, this one to star Billy Bob Thorton. The show is based on a successful podcast called “Boomtown,” which examines West Texas’s oil “boomtowns.” There is some confusion as to whether it’s a Yellowstone spinoff. Some say yes. Others say no. I guess we’ll have to wait until the show airs in 2024 to find out. And, of course, the show will be on Paramount Plus.

Writer: Taylor Sheridan (based on the podcast by Christian Wallace)

Details: 51 pages

I don’t think anyone in history has had this many shows produced in this amount of time. Maybe Darren Starr? I guess there’s no point in stopping. If they’re going to greenlight everything you write, just keep going. Let’s try to get 50 shows on this Paramount network.

My mind always goes to money on these things. If you have one hit show, that’s worth 8 figures over the course of your life. If you have two, do the math. Three? Four? Now you’re starting to approach 9-figure territory.

So what’s Taylor Sheridan’s secret? I would love to know. I wouldn’t mind having a hit show on TV. Let’s see if we can find out together after reading… Land Man.

The most American name ever, Tommy Norris, is 55 years old and a fixer for the oil companies in West Texas. When we meet him, he’s been dragged to a remote location where he has a meeting with a cartel kingpin, all while wearing a bag on his head so he doesn’t see the guy.

The kingpin wants to know how these land rights work. Cause, as far as he knows, he owns this land. But Tommy explains to the guy that he only owns the top of the land. Tommy’s employers, the oil tycoons, they own what is underneath the land. And, therefore, they are ultimately in charge of how the rules are made.

After getting out of that situation with only a black eye, Tommy is informed of a snafu in a nearby township. A drug plane landed on a remote road where they quickly unloaded their cocaine onto a coordinating van. But because they were set up just over a hill, they didn’t see an oil-truck scream over the top of the hill before it crashed into them, blowing everybody up.

Tommy now has to figure out how he’s going to navigate that issue.

As he’s putting together a plan, his ex-wife calls and reminds him that he has to take their 17 year old daughter, Ainsley, for the weekend. Ainsely is a bit of… let’s just say that if her parents don’t watch out, she’s going to end up in porn. So she needs a lot of attention.

Unfortunately, when Ainsley shows up, she does so with her new Top 50 football recruit Greek God of a boyfriend, Dakota. And now Tommy has to keep his eyes on both of them. While this is happening, little does Tommy (or Ainsley, or his ex-wife) know, that his 22 year old son, who just got a job as an oil rig mechanic, is involved in a giant explosion after a malfunction. Whether he’s okay or not will be left a mystery until…. Episode 2.

I have one question for you. Is Taylor Sheridan screenwriting Superman?

This guy is so talented. I don’t know where in the millions of pilots he’s written he fit this one in. But if this is one of his many “belt-it-out-in-a-week” scripts, I don’t know how he does it. Because, normally, the problems you associate with rushed writing are a lack of specificity. A sloppy plot. Thin characters.

That isn’t the case here.

Right off the bat, we get this highly specific monologue. This is Tommy explaining the land deal to the cartel people:

“First they’ll hire Halliburton to build files on you f—king assholes the FBI dreams about having, then they’ll send thirty tier one operators from Triple Canopy to bust you like fucking pinatas. And if any of you dipshits make it back to Mexico they will blow up your house with a drone. While your family is in it. … It costs about six million to put in a new well, they’re putting 800 of them right fucking here … That’s 4.8 Billion in pump jacks. They’ll spend another billion on water, housing, and trucking. At an average of 78 dollars a barrel they will make 6.4 Million dollars a day. For the next fifty fucking years. The oil company is coming. No matter what.”

I call this the Gollum Effect. Peter Jackson famously put 70% of the CGI focus on Gollum’s very first scene because he knew if he could convince you in that moment that Gollum was real, it wouldn’t matter, later on, if his special effects got fuzzy. You’d already bought in.

Same thing here. By being highly specific about this world right away, we immediately buy into it. So even if some of that specificity becomes more generalized later on, we’ve already bought in. But the thing with Sheridan is that he keeps the specificity going! Which is so noble because it’s so hard to do. Unless you know these details inherently, you have to go look them up then figure out how to craft them into a convincing monologue. That takes research time and rewriting time, since monologues never work on their first go. Yet here he is, able to do this in record time. It’s amazing.

Another thing I love about this pilot is the contrast. Technically this isn’t a high concept idea. It does feel larger than life since so much money is involved. But it’s not a splashy idea by any means.

But one way you can combat that in TV is to create an enormous contrast in the worlds your main character has to deal with. Remember Alias? On that show, the main character had to deal with this extreme spy world only to go back home and deal with everyday life, like frustrated boyfriends.

That contrast works as a powerful engine for storytelling because we can’t believe someone who’s just had to kill a person now has to patch things up with their best friend who’s mad cause she didn’t come to her birthday party.

Same thing here. The opening scene shows us how dangerous Tommy’s job is. He has to have one-on-one meetings with insane cartel leaders because they operate on the same land that he’s drilling under.

But then he has to go back home where his firecracker of a 17 year old hormones-on-overdrive daughter is ready to bang anything in sight. And now he has to figure out how to deal with that, both internally and externally. That contrast really made this pilot pop.

Sheridan also understands the little tricks of the trade to keep the reader interested. A great dramatic device to use is first setting up a certainty. You say: X IS GOING TO HAPPEN. Then you make sure that when X arrives, it arrives with a complication, Y. In other words, nothing should ever be certain in dramatic writing. Things should always be happening that weren’t in the plans.

In this case, Tommy’s ex-wife calls and says that their daughter is coming to stay with him this weekend because she’s going on vacation. He didn’t know this and tries to get out of it. “She 17. She’ll be fine home alone.” She then shows Tommy a picture of Ainsley’s new boyfriend, who looks like he’s going to bed every woman in Texas and says, if Ainsley stays at home by herself, these two will have 72 hours by themselves, and who knows what could come out of that. So Tommy agrees and flies Ainsley in.

Except, the second Ainsley walks off the plane, we see the boyfriend emerge behind her. This is the complication (the “Y” in the equation). The boyfriend is going to be staying with Tommy as well. These kind of dramatic reveals are especially important in television, which is character-based. A lot of the creative choices you’re going to be making in TV revolve around character. So this is definitely a tool you want in your tool shed.

Everything I just mentioned, I enjoyed. But if that wasn’t enough, you also have this mystery of this plane-truck-van collision that happened. How is that going to play out? That’s a good lesson as well. Throw a mystery into your pilot. It’s one more reason that we have to tune into episode 2.

The only thing I’m confused about when it comes to Sheridan is the length of his pilots. Most of the pilots I’ve read from him hover around the 50 page mark. I’m not sure why he does that. Because I wouldn’t mind 10 more pages here. The plot does feel a teensy bit light. Since TV is all about character, you can always stuff one more character plotline in your pilot and build that character up.

Maybe it’s something Paramount requests. I don’t know.

Either way, this was a really good pilot. This guy is one of the best screenwriters working today.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: As we’ve discussed before, you can tell a good writer by the way he writes descriptions. Look no further than this character description of Tommy’s ex-wife…

Hard to say how old Angela is, she commits most of her existence to keeping that a complete mystery.

Deductive reasoning puts her well into her forties — fifties even, but good hair, better skin, a great boob job and one hell of a personal trainer make us doubt the math.

Genre: Action

Premise: In order to clear his name and re-enter the Order, John Wick will have to take on the guy at the top of the program’s pyramid, the psycho, Marquis Vincent de Gramont.

About: The John Wick franchise had its biggest weekend ever, scoring 73 million bucks. This means that if you were betting on the “more money than kills” wager circulating around Las Vegas, you’d be short about 20 million, as Wick killed nearly 100 million people in this movie. Director Chad Stahelski swears this is the last John Wick film. “American Assassin” screenwriter Michael Finch teamed up with Shay Hatten to write it.

Writer: Shay Hatten and Michael Finch (based on characters by Derek Kolstad)

Details: 2 hours and 50 minutes long (no seriously!)

Are movies back??

Has the answer, all along, been to just ‘dude’ it up?

Hollywood has bent over backwards these past five years to de-masculinize the moviegoing experience. “Terminate the testosterone” was the operating slogan. If you wrote a script without a prominent female character, the studio would toss it then euthanize you, not necessarily in that order.

Well, it turns out that when you give your core audience what they want, as opposed to try and make a movie for everyone, you signal yourself as a flick that knows what it is and celebrates that.

John Wick 4 is a movie where you go get your dude friends, you head to Taco Bell, you buy a bag of taco carnage. You hide all the tacos in your pockets. Then you head into the theater and have John Wick Taco Time. 69% percent of the audience who saw this flick were dudes.

So which was better, the tacos or the movie?

The plot breaks down like so. The captain of all the Continental Hotels, Marquis, who lives in France, tells the New York Continental manager, Winston, that his hotel is no longer in operation since he failed to kill John Wick in the previous movie. He then blows the hotel up.

Marquis then force-hires this guy named Caine, who’s blind, and was once the best assassin in the world, and tells him to kill John Wick. Cut to Japan, where John Wick visits his old friend, Shimazu, who runs the Japanese Continental (it’s like White Lotus! Even Jennifer Coolidge was there!). Caine and his team descend upon this hotel which results in an outright war.

John Wick escapes and, after a side quest where John has to reclaim his name or something, Wick enacts prima nocta, whereby Marquis must battle him in a duel. If John wins, he’s back in good standing again. Marquis is a fan of Amelie so he sets up the duel at Sacre Couer. Marquis then swaps himself out for Caine. And then… well and then we have our shocking ending.

I don’t know if I have ever, in my life, seen a bigger gap between the quality of a script and the quality of a production. The screenwriting here is so bad. Yet the direction is so good. How do I reconcile this madness???

I suppose, if we’re being honest, the John Wick franchise was never about the writing. It is about a guy who goes after the Russian mob because they killed his dog. I’ve met third graders with better starting points for stories. Instead, the series focuses on its icy cool directing style and the “gun-fu,” which has risen to all new heights in John Wick 4, whereby somehow people are able to withstand 15 shots to the gut before they die.

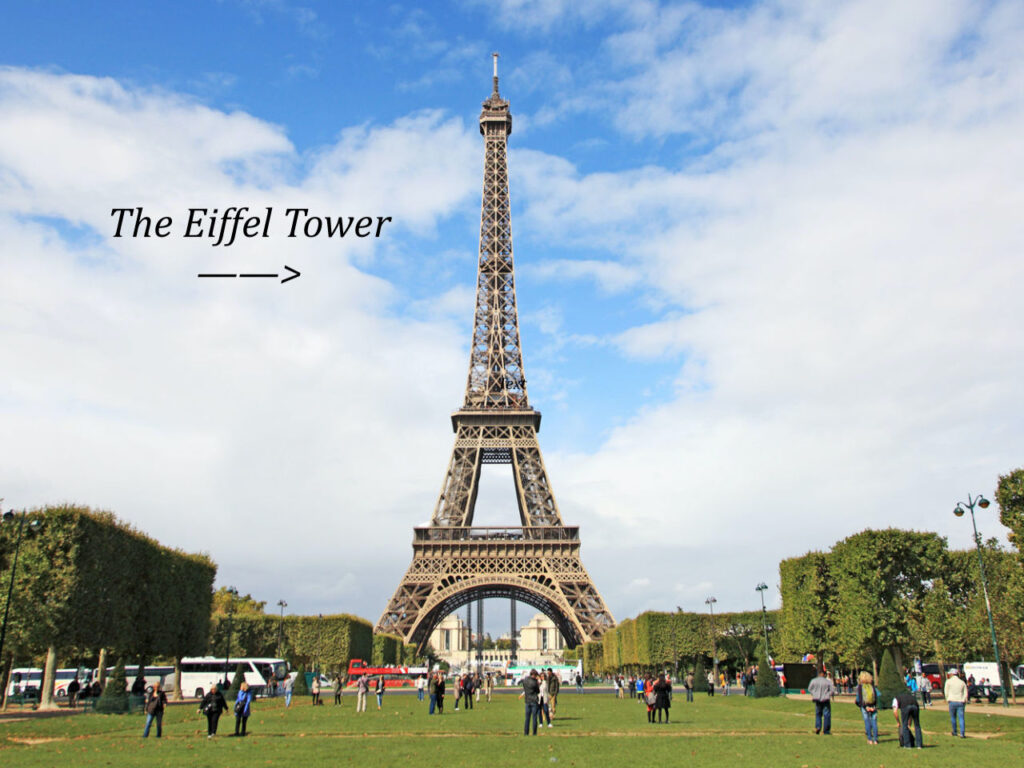

Pretty much nothing makes sense in this movie. There is a team of people who monitor assassinations who have an office that takes up an entire floor OF THE EIFFEL TOWER. I don’t know if you’re familiar with the Eiffel Tower but there are no private floors.

Therefore, this group of people are doling out 25 million dollar hits in front of anyone with a pair of binoculars. And, oh yeah, this office is run by 1950s pin-up cosplayers who ARE AMERICAN. So I guess France rents out a see-through office in the Eiffel Tower to American cosplaying assassins. Sure. Why not?

Or this was my favorite part. At the beginning of the movie, John Wick is hanging out in an abandoned underground subway when Lawrence Fishburne shows up with a freshly dry-cleaned suit for him, then proceeds to light a match and ignite a pre-arranged fire triangle on the ground that has ABSOLUTELY ZERO PURPOSE. Literally nobody benefits from this triangle of fire. And yet there it is.

But wait, there’s more! There is a fight to the death that takes place IN THE MIDDLE OF A CLUB. And everyone just keeps dancing! Two guys pummeling each other into a bloody pulp and no one bats an eye. At one point, after John Wick had fallen off a 40 foot railing, some guy two feet from him was more concerned about his twerking technique than checking to see if John Wick was okay.

One would think this would place John Wick 4 squarely into the “crap” category, which is so bad that it needs to pass special arbitration rules to even be included in a Scriptshadow review. But that wasn’t the case.

There’s something undeniably special about the production value of this movie. It joins the ranks of James Bond and Mission Impossible of showing us just how magical an experience REALNESS has on a film.

Every. Single. Location is stunning. The framing of every shot is beautiful. The production design is second-to-none. The costuming is excellent. The cinematography is so good.

Even when the set dressing is cliche, it’s done so much better than everyone else’s version of it, that it still leaves an impression on you. For example, John Wick walks into a church and every single candle in the place is lit. Seen it a million times. But it was done on so much steroids here that your jaw was on the floor.

There was a moment, though, that exposed this practice. I don’t even remember who was in the scene. I think maybe Marquis and Winston. The scene was pure exposition. It was there to set up *what needed to happen next*. It was so nuts and bolts plot exposition that Stahelski decided to set it inside a gigantic equestrian practice barn. As our characters work out the plot, these equestrian riders, for no purpose whatsoever, start riding around our two characters as they converse.

Make no mistake, it made for a visually interesting conversation. But when you’re going to these lengths to hide the fact that your dialogue is boring, you’re doing it the wrong way. What you want to do is find a dramatically interesting scenario that you can use as a vessel to hide your exposition.

For example, there’s an earlier scene where a “tracker” who claims to be able to find John Wick, comes to the Marquis to negotiate a contract. In that scene, there’s something dramatic going on – a negotiation. Both men have big egos. Neither likes the others’ terms. As a result, the negotiation escalates quickly. All of this while exposition is being given (their discussion is yielding what happens next in the story).

That’s how you do it. You can’t just put shiny things on a screen and hope they distract the viewer from the fact that you’re force-feeding them three minutes of dead-boring exposition. You must entertain them while feeding them. To highlight the ineffectiveness of Stahelski’s strategy, I don’t remember a single thing they discussed in that scene. But I remember what happened in that Marquis-Tracker scene down to smallest detail.

Dramatize scenes people. It makes a world of difference.

For me, what sets these movies apart is originality and cleverness within set pieces. The two set pieces that stood out to me were, one, Caine’s first sequence in the Japanese Continental Hotel. Remember, Caine is blind. So he carries these little motion sensors which he slaps onto walls. Then he lures his prey into these rooms and waits until they pass the sensors, which beep a noise, which tells Caine exactly where to point and shoot. I thought that was fun and clever.

And even though I was making fun of it earlier, I liked the John Wick club sequence for its bombastic over-the-top boss fight. John takes on this gigantic man who just won’t die. And they fight each other all over the club. The gigantic guy reminded me of boss fights in video games. You just keep hitting the guy and nothing happens. I’d never quite seen a scene like it in a film. And that’s all I’m asking for. You don’t have to give me something totally original. But at the very least, it needs to be original-adjacent.

Such a mixed bag with John Wick 4. The running time here is so ludicrous, it’s hard not to laugh at it. The number of kills could’ve been cut in half and nothing would’ve been missed. But I guess if this is your last Wick, you gotta go full Wick. And that they did!

[ ] What the hell did I just watch?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the price of admission

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Shay Hatten says that Keanu Reeves is the king of demanding less, not more, when it comes to dialogue. In the first film (before Hatten came on board), there was a five page monologue for Keanu and Keanu ended up convincing the team that all he needed to say was, “Uh huh.” When it comes to how much, or how little, dialogue you should write, “less is more” is, historically, the more effective approach. Now you can get carried away with that. But the key is to be honest with yourself. Are you only writing that monologue because it’s a movie and you feel like that’s what happens in movies? The character gets a big monologue at this moment? Or are you writing that monologue because it’s something the character would really say? Lean into the latter. Because when characters start saying things that they don’t really need to say, that’s when dialogue dies on the screen (and on the page). There must be purpose behind the words for them to matter.

Last month, we had two winners. There was Rosemary, the actual winner. And then there was Fear City, which got second place but was able to attain the nearly impossible Showdown rating of an “Impressive.”

Who will emerge this month? I, for one, can’t wait to find out!

Every second-to-last Friday of the month, I will post the five best loglines submitted to me. You, the readers of the site, will vote for your favorite in the comments section. I review the script of the logline that received the most votes the following Friday.

If you didn’t enter in time for this month’s showdown, don’t worry! We do this every month. Just get me your logline submission by the second-to-last Thursday (April 20 is the next one) and you’re in the running! All I need is your title, genre, and logline. Send all submissions to carsonreeves3@gmail.com.

If you’re one of the many writers who feel helpless when it comes to loglines, I offer logline consultations. They’re cheap – just $25. E-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com if you’re interested.

Are we ready? Voting ends Sunday night, 11:59pm Pacific Time!

Good luck to all!

Title: Chipped

Genre: Comedy

Logline: When the sitcom about a talking possum that gave Blair Murphy her fifteen minutes of child stardom 30 years ago gets rebooted without her, she foregoes her aversion to the internet and installs a chip in her brain that livestreams her every moment on social media in a desperate and ultimately disastrous attempt to claw her way back to relevance.

Title: Integrating Anna

Genre: Sci-Fi

Logline: Set fifty years in the future, an optimistic young man brings his A.I. fiancée home to meet his technophobic family.

Title: Blood Moon Trail

Genre: Thriller/Western

Logline: In 1867 Nebraska, a Pinkerton agent banished to a desolate post for an act of cowardice finds a chance at redemption when he decides to track down a brutal serial killer terrorizing the Western frontier.

Title: Compulsion

Genre: Horror

Logline: After suffering a near fatal heart attack, a peaceful woman discovers that her new pacemaker requires consistent blood sacrifices in order for it to operate.

Title: Kill Box

Genre: Horror/Thriller

Logline: Submerged by a tsunami while commuting along the San Francisco bay, a bus driver and his passengers must find a way to safety when they realize the tsunami has brought with it a pack of bloodthirsty sharks.