Search Results for: F word

One of the questions I’m often asked is, “Do I need to obtain the rights to someone’s life in order to write about them?” I’ve brought in Lisa Callif, a partner at the law firm of Donaldson and Callif, to help answer that question. Callif has helped steer many independent producers through this process, including on such films as “Devil’s Knot,” the real life story of three teenagers who were wrongfully convicted of killing three boys, and “Welcome to New York,” about Dominique Strauss Khan.

SS: Let’s start off simple. A lot of writers ask me, “Can I write about a real life person or do I need the ‘rights’ to them?” Is there a simple answer to this?

LC: The simple answer is yes. The law does not require you to obtain life story rights to make a movie that accurately portrays that person.

SS: What is one of the biggest misunderstandings about obtaining the rights of a person to write a movie about?

LC: That a life story rights agreement is an acquisition of an underlying right. The facts of a person’s life are in the public domain, so there is no need to acquire them. Rather, it is a person’s waiver of certain personal rights and an agreement by them to cooperate and consult in the making of the film of which they are a subject. The agreement is formatted like a normal acquisition of underlying rights because that is the tradition in Hollywood, and because most lay persons have the notion that they own something called “life story rights.” Besides, no one would sign it if it were correctly labeled as a “waiver of right to sue no matter how badly you muck up my life.”

SS: I notice that in almost every case with the studios, when they have a movie about a real-life person, they’ve either purchased a book about that person or obtained life rights through the person themselves or the family. If it’s okay to write about people without obtaining official permission, why do they do this?

LC: Despite one’s legal right to make a film without life rights, there are lots of good reasons to obtain them. Let’s look at the two most important: first, when you purchase someone’s life story rights, they waive the right to file a lawsuit based on a violation of their personal, privacy and publicity rights. In fact, it is the waiver of the right to sue you, no matter what you do to the person’s life story, that is at the heart of the life story rights agreement (especially for a deep-pocketed studio). This waiver not only provides you (and the others involved in the film) with great protection, it makes it easier to obtain Errors & Omissions (E&O) insurance, which provides you with coverage if anyone portrayed in your film decides to sue you. Second, the agreement gives you access to the person about whom you are writing. The person who lived the story always has information that is not publicly known and perhaps more interesting than what has already been published. Simply put, you often make a better movie with the participation of these people.

SS: Let’s take a specific example. Studios are constantly trying to make movies about Martin Luther King and getting rejected by the family. Why don’t they just ignore the family and make the movie anyway?

LC: Well, they just did. As I understand it, the filmmakers of “Selma” did not have the rights from the estate. That said, the hesitation to make a film without rights is the fear that someone will get upset and file a lawsuit. No one wants that. The King estate is very protective of its rights and not afraid to file a lawsuit. However, if a story is told accurately, the chances of a lawsuit lessen dramatically. It’s only if the filmmaking is sloppy or people aren’t honest that you can really get in trouble.

SS: But I’ve heard things like that the family owns the “I Have a Dream” speech and that you can’t use any parts of that speech in print or movies without paying them ridiculous amounts of money (I heard a recent quote of 300 words from the speech were going to cost one journalist $10,000). I’d consider that “facts” from the character’s life, but maybe speeches fall under a separate category that’s treated differently by the law?

LC: It’s true that the MLK estate has established copyright ownership over that speech, however, that would not prevent a filmmaker from using portions of it pursuant to fair use (of course, the use would have to fall within the parameters of fair use and that is something we would determine based on how it is used). And yes, a speech is quite different from “facts,” especially a speech that is written before it is recited. Under the 1976 copyright act (our current law), copyright protection attaches the minute you put pen to paper. It is debatable whether the “I Have a Dream” speech should have been granted copyright protection due to certain formalities that may or may not have been met, but the bottom line is that the estate was able to establish copyright ownership over that speech. The fact that MLK delivered that speech on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial in 1963 is a fact and may be used freely, but his written words, which have been copyrighted, may only be used with permission from the estate or pursuant to fair use.

SS: If there was ever an opportunity for a subject to sue over a movie about them, it was The Social Network. Mark Zuckerberg had gone on record as saying everything about that movie was false. Here’s a guy with a multi-billion dollar bank account. A lawsuit is a drop in the bucket for him. And there seemed to only be a positive outcome for him filing a suit (he repairs the bad image that the movie painted of him). Yet he did nothing. Did the studio dodge a bullet or did Zuckerberg not sue because he had no legal cause?

LC: I didn’t have any direct involvement in this film, but I would certainly guess it was the latter. There are potential other reasons as well – perhaps Zuckerberg/Facebook have other skeletons in the closet that they didn’t want known. Litigation is not only costly, time consuming and lengthy, but it also has the potential to expose things a person may want to keep private. Perhaps there were business and public relations reasons they did not file. Is it the right move for Facebook to sue, even if some of the allegations made in the film were false? How would Facebook users view that? Do Facebook users care about the allegations made in the film? Did it harm their business? Obviously not. Would it have if they filed a lawsuit? Probably not, but maybe litigation would not have provided any real benefit to the company.

SS: Just the other day, I reviewed a script called “Pale Blue Dot,” that covered the real life story of an astronaut love triangle (the famous “astronaut drove 500 miles in a diaper” story). The writers, however, changed all the names. Is this a simple way to avoid a lawsuit? Can I pick any real life story and simply change names and be immune from litigation?

LC: Short answer, no. Simply changing a name does not get a filmmaker even close to being safe. If you really don’t want a person to be recognizable, then you must make that person unrecognizable. Changing a name doesn’t do that.

SS: Last year, one of the studios optioned a huge article about the famous Venezuelan case where a dead man accused the president of assassinating him in a posthumous Youtube video. Do they now officially “own” that story? Would a rival studio be able to release their version of the exact same story without an option on any material? Or would the first studio be able to sue them?

LC: The studio will own that story as it was told by the author. However, the studio won’t own (and no one will own) the facts of that event. Anyone can write about these facts without obtaining permission to do so. What another filmmaker cannot do is take the way in which those facts were told in the article and use that expression without permission. The essential ingredient present in creations, but absent in facts, is originality. The question to ask yourself is – am I telling a story that has already been told? Or am I using facts to create my own story?

SS: One final question. There was another script sale awhile back that covered the real life story of that girl who freaked out in a Los Angeles hotel elevator and was later found floating dead in the hotel’s water supply. The writers just went ahead and created this whole ghost story out of it (with supernatural elements and all). So can you just take a real-life person and create an entirely made-up story around them?

LC: Because that girl is deceased, the filmmaker has a lot more leeway. When a person dies, their personal rights die with them, including defamation. One does need to be cautious about claims by heirs and others connected to the subject who are still alive. But if you’re writing about a deceased public figure, you can pretty much write anything. Also, even with living subjects, a filmmaker can take some creative liberties in establishing elements that are unknown (such as conversations). Courts call this “fictional embroidery.” This is permissible so long as the fictional elements naturally flow from the known facts and do not violate the personal rights of that individual.

I hope this was helpful. I might be able to send a couple of follow-up questions Lisa’s way. I’ll do so for the two most upvoted questions in the comments section and put those answers up within the next 24 hours. ☺

A rare treat. An extremely solid amateur script! But will not owning the rights to the material doom the screenplay??

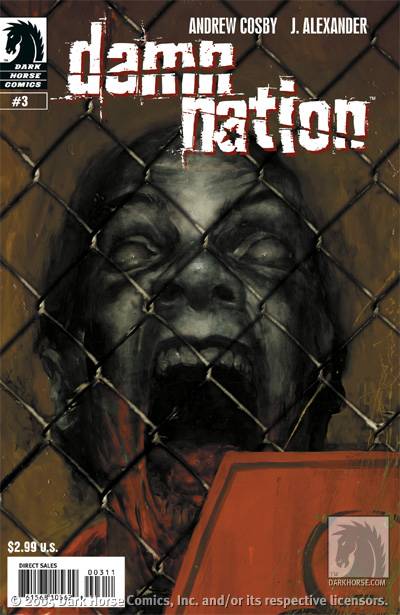

Next week is a SPECIAL WEEK here on Scriptshadow. It’s WEIRD SCRIPTS WEEK. I’ll be reviewing five really strange scripts, saving the weirdest and oddest for Friday. Your life will never be the same after you hear about that last script, I promise you. This means there will be no Amateur Offerings this weekend. So check out Damn Nation instead. It’s a good script!

Genre: Horror/Action-Thriller

Premise (from writer): Five years after a plague has overrun the United States, turning most of the nation into feral vampiric creatures, a Special Ops unit from the President’s current headquarters in London is sent back into the heart of the US in a desperate attempt to find a group of surviving scientists who claim to have found a cure for the disease… but not everyone wants to see America back on its feet.

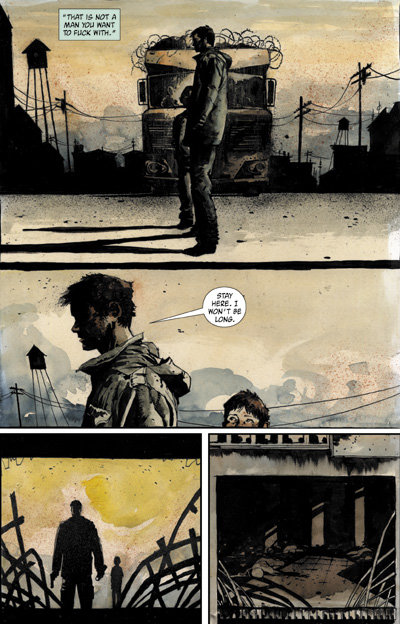

Why You Should Read (from writer): I believe screenplays are evolving. With the advances of technology in the last couple of decades such as the internet, computers, ipads, smartphones, etc, screenplays can be more than words on paper, they can be visual and even interactive experiences. I’m not the first and I won’t be the last person to integrate artwork into my screenplay, but I think this approach, if done right, can add a lot of value to a project. Integrated artwork is just the tip of the iceberg though. I believe soon people will be adding a lot more elements, such as photo references, storyboards, video, sound effects, music, and other audio-visual components embedded into their scripts. The possibilities are endless. — However, I know that my view on things is going to be vastly unpopular right now. I think most people will have an old school attitude and believe that writers should write, leaving the fancy bells and whistles to someone else. — With that said, I do believe nothing is more important than the words themselves. Above all else, I hope my script is judged on the words, not the images. Everything else I’ve added is just a bonus.

Writer: Adam Wax (Based on the comic, “Damn Nation,” written by Andrew Cosby and illustrated by J. Alexander)

Details: 110 pages

I guess you could say today’s entry is a little controversial. We don’t usually review adaptations on Amateur Friday. But there’s nothing inherently wrong with writing one. I know some people get upset by it but as long as you give credit where credit is due, which Adam does, it’s fine.

As far as whether it’s legal to adapt something you don’t have the rights to – it’s perfectly legal. If you went and wrote your own Fifty Shades of Grey script tomorrow, nobody’s going to come knocking at your door. The only time it becomes illegal is if the studio buys it and turns it into a movie without obtaining the rights. And even then, it’s not you who gets sued, it’s them.

Wax has also decided to infuse artwork from the comic into his script. As I’ve stated before, I have no problem with this either. I think, under the right circumstances, art can enhance the read. I just wasn’t a particular fan of THIS art. I’d prefer art that actually gives me a clear idea of what’s going on. This art here is almost the opposite – as evidenced here.

The setup for Damn Nation is pretty straight forward. Five years ago, a lost Russian tanker wanders into U.S. waters, full of dead bodies. When a group goes to inspect the ship, they find that these “dead” bodies aren’t as “dead” as they thought. We cut to five years later, where we learn that that event was the beginning of a fast-acting virus that took down the entire United States.

Back in Britain, where the remainder of the United States government now resides, they receive a signal from Buffalo, New York, with a simple message: “We have the cure.” The Americans and the Brits put together a team of about a dozen soldiers and send them off to Buffalo to see if there’s any truth to this message.

The team is led by the always cynical Captain John Cole. He’s joined by the non-shit-taking Lieutenant Emilia Riley, a Brit who’s not a huge fan of the American way. The two command a group of both Americans and Brits, and head into Buffalo where they immediately find our scientist with the cure.

Except that’s where shit starts going wrong. A sub-division of the team turns on them, killing everyone within sight. They try and kill Cole and Riley, who just barely escape with the doctor, a few other soldiers, and the cure. We eventually learn that the Brits, the Chinese, and the Russians, like this new world where the U.S. is no longer a player. And if there’s a cure, that puts the U.S. back in the mix.

Cole and Riley are thrust into a dangerous country where these… things lurk around every corner. They’ll need to come up with a plan not only to avoid them, but find a way to safety, and find someone who actually wants to use this cure to save the United States.

In the spirit of being completely honest, permission-less adaptations are usually the worst scripts I read. I’m not sure exactly why this is, but my guess is, these scripts tend to come from first-time screenwriters who fall in love with a property (movie, comic book, what have you) and want to write a movie in that universe. They do this before learning how to actually screen-write, which is why the scripts are often complete messes.

My advice to writers thinking about adapting a high-profile property you don’t have the rights to: don’t do it. I can guarantee that the rights to anything you’ve found are already owned by some producer working for some studio, which means you have approximately ONE BUYER for your script. If that one buyer doesn’t like what you’ve done, you’re shit out of luck.

There is a less cynical side to the approach, though. If you write ANYTHING that’s good, whether it sells to that single buyer or not, the town will take notice. And while you may not sell this specific script, you’ll get tagged as a good screenwriter and get some meetings out of it.

I don’t know where Adam Wax is in his screenwriting career, but he deserves some meetings after Damn Nation. This script is good. The first word that comes to mind is: polished. This isn’t something that was thrown together quickly, like so many amateur scripts we read here seem to be. Rather, there’s a clear structure to the story, and Wax moves it along quickly.

We start with that great teaser – A Russian boat that’s been lost for 15 years. Inspecting that boat to find 200 dead bodies that suddenly come to life. If that doesn’t grab you, you are incapable of being grabbed.

We don’t waste any time when we jump to five years later either. We immediately jump to the “cure” signal and within pages, our team is on their helicopters, heading to the U.S. Spec scripts HAVE TO MOVE FAST. And Damn Nation eschews the Prius approach in favor of the Lamborghini.

The first big twist is maybe a little predictable (the soldiers turning on their leaders), but Adam’s such a good writer, he makes it work. And it places our characters into a seriously terrifying situation – being alone in a country dominated by blood-sucking creatures with no one to come save them.

I often discuss on this site using ideas that DO THE WORK FOR YOU. This is the kind of idea that does the work for you. Putting your characters in this kind of peril ensures that you’ll have a bevy of terrifying scenes and sequences. Every moment counts. Every wrong choice could lead to death. There’s never a moment here where the audience can sit back and relax, which is a sign of a really good story.

Some of the character stuff is really good too. For example, Captain Cole isn’t just some tough-as-nails vanilla captain. He learns that the whole reason he was picked to lead this mission is because he’s been such a terrible captain (killed two platoons in Afghanistan). He was chosen for the specific purpose of ensuring failure. Cole is going to have to dig down deep and overcome all his demons and past failures in order to prove to others, but more importantly, himself, that he can lead.

If you’re a fan of The Walking Dead, 28 Days Later, or really any post-apocalypstic literature, I can guarantee you’re going to LOVE THIS. I could see this being a hit movie TOMORROW. But I don’t know who owns Damn Nation, and I don’t know if whoever has the rights plans on making the movie anytime soon. But they should. And they owe it to themselves to at least check out Adam Wax’s version.

Script link: Damn Nation

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: I’ll say it again, guys. A spec script NEEDS TO MOVE QUICKLY. The specs that never seem to slow down, that never allow the reader to sit back and relax – these scripts have a HUGE advantage over the slow-moving specs with stories that take forever to get going, and which spend too much time sitting around in that second act. If you can, I’m BEGGING YOU to infuse URGENCY into your spec idea. Urgency and specs go together like peanut butter and jelly.

The absolutely FREE Scriptshadow 250 Screenplay Contest deadline is just 56 days away! Make sure you’re preparing your entries!

A lot of what we talk about here at Scriptshadow comes from a reactionary place. We assess someone’s work and then discuss how it either a) worked or b) didn’t. And if it didn’t, we discuss how it could’ve been fixed, or how it could’ve been done better. This is all well and good, and we certainly learn a lot from it. But it doesn’t address one of the hardest things about screenwriting: the blank page.

Staring at a blank page is a whole different ball of wax than trying to come up with a solution to a bad scene.

There are two types of “blank page” problems. There’s the “On the fly” blank page problem and there’s the “Outlined script” blank page problem.

The “On the fly” problem refers to writers who are writing their script on the fly. They didn’t start off with an outline. They had their idea and figured they’d jump straight into the script. This method is notorious for leading to a lot of blank page problems. Since you didn’t outline, you have no idea where your script is headed, and when you don’t know your destination, it’s hard to map out a route to get there.

For this reason, the writer eventually runs out of scenes (curiously, they almost always peter out around page 45), and subsequently start “grasping at straws.” They write to shock, they throw a twist or two at the reader, all to energize what they perceive to be a dying story, not realizing that it’s the lack of direction in the first place that’s the problem.

To these writers I say, “This is why you outline.” You outline to destroy the blank page. If you’ve already figured out your ending, and you’ve come up with a general idea for the majority of the scenes in your script, you’ll at least come into each scene with a plan. And plans mean less blank pages.

If outlining scares you, here’s another option. Make sure that every character in your screenplay HAS A GOAL. If you give every character a goal, then every time you cut to one of those characters, you’ll know what scene to write to push them closer to that goal.

If you know, for instance, that your 5th most important character, Tracy, is desperately trying to make enough money to pay for college tuition next year, then you know to put her in a few job interviews. And if she doesn’t get hired, and subsequently gets more desperate, you know she might start doing some unsavory things to get that money.

On the contrary, if all you know about Tracy is that she’s your main character’s sister, then when she comes around, you won’t know what to do with her, and the story will drift or come to a stop when she arrives.

To use a recent example, look at Mad Max: Fury Road. The goals were clear from the start. Furiosa wanted to get back to her hometown. And Max wanted freedom. The bad guy, of course, wanted to get his five wives back. Every scene was dictated by the desires of those three characters, which is a big reason why not a single scene in that movie felt wasted.

Now if you’re a seasoned screenwriter, outlining is a huge part of your process. And for the truly hardcore, you’ve likely outlined every scene in your script (scene 1 to scene 60!). To these writers, having no idea what to write next isn’t really the problem. The problem is HOW to write what you write next.

Let me give you a real world example. A couple of weeks ago, a writer came to me needing to write a scene that took care of two things – introducing his main character’s wife, and conveying the fact that the two were struggling financially.

Notice that we know what to write, but we don’t know how to write it. I mean sure, we could take the obvious route. Our main character comes home from work, and there his wife is, at the dining room table, bills spread about everywhere, looking dire. Does the job, right? Sure.

But is it a good SCENE?

No.

Any time you give us the same scene/solution that the average Joe on the street could’ve come up with, you’ve given us a boring scene. Even the best version of that scene gives us information (exposition) and nothing more. Which puts us right back at the blank page. So what the hell do we write?

I’m going to let you in on a big secret here – the key to writing a scene that destroys the blank page. Are you ready?

CONFLICT

You want to approach your scene with the goal of injecting some conflict into it. And by conflict, I mean an imbalance that needs to be resolved. Maybe one character is mad at the other and starts yelling at them. Maybe one character is mad at the other and is passive aggressive towards them. Maybe one character is hiding a secret from another character. Maybe the two characters are avoiding talking about something. Maybe the characters desperately want to be together but can’t for some reason. Maybe the characters are fighting off a common enemy.

Conflict comes in many forms. But the important thing is that once you include conflict in a scene, you move away from merely conveying information, and you instead add an element of entertainment. Telling us that these characters are in financial straights is boring. Having one of the characters fed up that they’re in financial straights and taking it out on their partner in a passive-aggressive manner, now you have a scene.

I can already see it. The wife doesn’t NEED to have these bills out for when her husband comes home. But she wants to make a point. She’s reminding him that he can’t keep ignoring their reality. They’re in financial straights and he’s got to do something about it. He shakes his head, storms by her, and all of a sudden we have tension in the air. We have conflict. We have a scene, even if it’s a mere quarter of a page long.

But let’s say that one of the things you ALSO want to convey in this scene is that our husband and wife characters love each other very much. Having them pissed off at each other may make for a juicier scene, but it conveys the exact opposite about their relationship than what you want. Okay, that’s fine. Just shift the conflict so that it’s external.

Maybe our husband gets home, and the neighbors are, once again, playing their music loudly. As our couple work out which bills they need to pay first to stay above water, the music only seems to get louder, until the husband can’t take it anymore. He storms over to the neighbors and tells them off.

Remember, the most boring scenes in any script are the scenes where nothing’s happening. And “nothing’s happening” is universal code for “No conflict.” So always look for an angle into the scene where some kind of conflict is taking place, even if it’s subtle. Assuming that you know what needs to happen next in your script, the right level of conflict could be the key to busting past that blank page.

How many writers does it take to write one disaster pic? A lot more than you think!

Genre: Action

Premise: After a massive earthquake hits the West Coast, a rescue-chopper pilot travels across the wasteland to save his daughter.

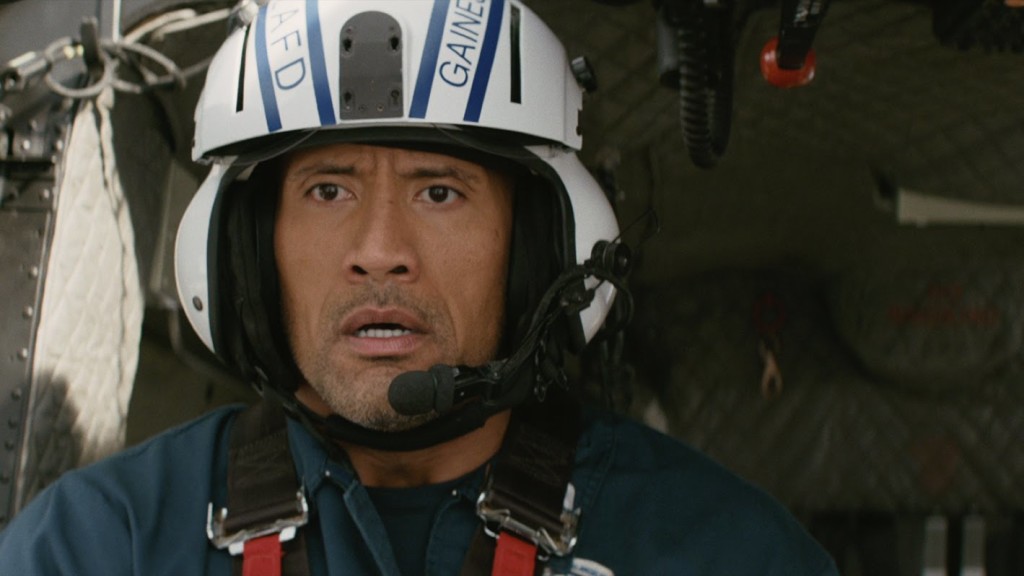

About: San Andreas came out this weekend and bested predictions with 50 million big ones (a good 10 million higher than most estimates). I guess you could say it was an AFTER-shock to analysts. Get it? Cause aftershocks are earthquakes? The film stars the most likable movie star in the business, The Rock, and was directed by The Rock collaborator, Brad Peyton, who worked with the muscled one on Journey to the Center of the Earth 2. While Andre Fabrizio and Jeremy Passmore wrote this draft, it looks like Carlton Cuse (of Lost fame) received final credit, with Fabrizio and Passmore having to settle for story credit.

Writers: Andre Fabrizio & Jeremy Passmore, revisions by Allan Loeb (10/26/11), Revisions by Carlton Cuse (11/02/12), Current Revisions by The Hayes Brothers 7/24/2013

Details: 108 pages

Reading the title page of San Andreas is a bit like reading a screenwriting earthquake. There were enough screenwriters here to fill up a WGA screening. And I suppose that makes sense. The disaster pic, once a staple of Hollywood’s plan to steal your mid-summer money, has become the green-headed step-child, an awkward mumbler of a personality in a world where dark-colored spandex reins supreme.

So the fact that the producers felt they needed to get as many screenwriting eyes on the script as possible should probably be seen as proof of their insecurity. I mean, didn’t Guardians of the Galaxy have just two writers?

What may have given them pause is the fact that they’ve actually scaled the disaster pic back. When the Emmerichs and Devlins of the world were in charge of mass cinematic disaster, they typically chose to take down the entire planet. This approach seems to have been endorsed by Damon Lindelof, who once said, “If you’re going to play in the summer sandbox, the stakes basically have to be the entire world.”

But here’s the thing about that. If the destruction is TOO sprawling, if it covers TOO MUCH surface area, it’s tough to wrangle in a story. You only have two hours to tell a story in a feature-length movie. If you want that movie to resonate emotionally – you probably want to keep things at least somewhat contained. Which is why San Andreas had the chance to excel where all these other destruction movies failed.

The quick plot breakdown for San Andreas is that Tom, a Los Angeles rescue-chopper dude, is reeling from the recent implosion of his marriage to Rachel, who’s since moved on to the incredibly rich and seemingly perfect Patrick.

This has been hard on their 21 year-old daughter, Blake, who’d like for nothing more than to have the family back together again. To add insult to injury, Tom has to cancel a father-daughter sorority function with Blake, forcing her to go with future step-dad Patrick instead.

The two head up to San Francisco, when the first quake hits, pinning Blake inside her car. So what does Patrick do? He gets the hell out of there, saving himself! Blake’s able to call her father and let him know where she is, and after The Rock, I mean Tom, saves his wife, the two head up to San Fran to save their daughter, and hopefully, their marriage!

The first thing I noticed about this is that they changed the names of the main characters. Here in the script, the parents are Tom and Rachel. In the script, they’re Ray and Emma. I’ve heard that changing character names is a trick writers use to improve their chances of getting final credit, since it appears to the WGA arbitrators as if more has changed than actually has.

I’m not saying that’s what happened here. It could just be someone didn’t like those names. But with the original writers usually favored to get credit, and Fabrizio and Passmore not getting it here, it is a little curious.

As for the script, I have to say, it’s not bad. I mean, this isn’t going to win any Oscars, but if there was an award for “best execution of a standard story,” I’d put San Andreas up there with any other screenplay this year. Every beat of this script hits like the heart of an Olympic athlete, which makes sense, since The Rock’s headlining it.

What you’re always running up against when you write a pure action flick is trying to find the emotional core of the story, which of course takes place with your characters. To this end, San Andreas does a solid (unlike the earth in the film) job.

We establish that Tom and Rachel are broken up, but there’s still a spark there. This is a nice dynamic to set up because it gives the reader hope. “Maybe,” they think, “They’ll get back together.” And if there’s a “maybe,” there’s a reason for the reader to keep reading.

Also, when you’ve got a marriage or a relationship that’s fallen apart, you want there to be an origin to that rift. In other words, you don’t want them to just be broken up because you, the writer, need them broken up for your story. There needs to be a reason.

Here, we find out that Tom’s other daughter died five years ago in a rafting accident. Tom wasn’t able to save her, and it destroyed them. Death of a daughter/son is one of the biggest reasons for couples splitting, so it makes sense here. This also buoys the action in the main plot, since we know that Tom isn’t going to let another one of his daughter’s die.

As far as covering this backstory in your script, it’s up to you. Some writers like to add that scene where the hero tells someone what happened. Some writers (Robert Towne in Chinatown), choose not to tell the story at all. It’s also up to you whether you want to tell the whole story or just a sliver of it, leaving it up to the audience to fill in the gaps (something I favor). But the important thing is that you, the writer, know it, so that the story beat feels authentic.

Here, the writers do something interesting. They give the explanation of this backstory to a third party, Blake. She tells it to a guy she’s running around the city with. This is favorable. When the character himself (what would’ve been Tom) tells the story of how he “couldn’t save her” (or whatever the story is), it comes off as overly melodramatic, even cheesy. By having someone else recall it, it feels less manipulative, and a bit more realistic.

From a structural standpoint in San Andreas (sorry, I had to go there), you could practically see the problems the writers dealt with as the script evolved. I’m willing to bet this story was originally relegated to Los Angeles, with Tom on one side of the city and Blake on the other. But the writers quickly realized that the story’s not going to last very long if all a helicopter pilot has to do is fly from one end of Los Angeles to the other.

So they added this storyline where Blake goes up to San Francisco, extending the earthquake all the way up the state. It’s choices like this that aren’t noticed by the average movie-goer and really what screenwriters get paid for. Cause the choice is a 2-for-1. It not only extends the distance between rescuer and rescuee, allowing for a more difficult challenge, but you now get to have the earthquake hit two cities, which doubles the entertainment value of the film.

Look, I’m not here to tell you that San Andreas is the best screenplay ever. But for what it’s trying to do, it does a really good job. I’d definitely recommend it to any screenwriter who’s writing an action script. Read it if you can find it!

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: When you’re writing an action movie (or really any “genre” type movie), don’t worry about being too “proper” with your prose. The read is supposed to be easy and light, so your prose should reflect that. I loved the way our resident seismologist’s office was described when we first meet him: “Roger’s sitting behind a desk. Tech shit and books everywhere.” Is this going to fly in a Harvard English Literature class? No. But all that matters in a script is that it tells me what I’m looking at. And I know exactly what this room looks like from this sentence.

Scriptshadow 250 Contest Deadline – 60 days left!

Today we have not five, but SIX Amateur Friday contenders. Why? Well, I’ll be honest with you. I don’t think writers are bringing it with their concepts. They’re not bad ideas, but remember, when you’re an unknown screenwriter, you need your idea to STAND OUT. You want it to be exciting and different. Heck, a good half-dozen of Thursday’s IRONIC LOGLINES, which seemed to have been made up on the spot, were better than all the loglines I received in my Amateur Offerings inbox this week. By expanding the field, I’m hoping to increase the chances of finding something good. Good luck to all!

Title: The Patron

Genre: Psychological Thriller/Crime Thriller

Logline: Fresh out of prison, a young Brooklyn artist attempts to restart his career, but his plans are derailed when a seductive older socialite blackmails him into murdering her husband.

Why You Should Read: I know in the past you’ve said you love a good psychological thriller, and this is a dark one with more twists and turns than Taylor Swift’s love life (okay, I guess it hasn’t been that exciting lately). I set out to write something in the vein of classics such as “Fatal Attraction” and “Basic Instinct”, but with a different, unexplored central dynamic – specifically, one between an older woman and a younger man (40s and 20s, respectively). The power imbalance between the characters due to her wealth and his recent incarceration only serves to heighten the conflict in the story. The script received high-enough ratings to place it on the Top List page of the Black List website; I humbly submit it here in hopes that it will be met with similar regard. On a final note, I was a Quarterfinalist in the 2013 Nicholl competition, so I’d like to think that my writing skill is at a level that won’t leave you wanting to gouge your eyes out. (Sorry to end with that disturbing image, but it felt appropriate).

Title: THE THREE DEGREES OF SEPARATION

Genre: Psychological Thriller

Logline: To help her sisters cope with their parents divorce an intelligent and highly imaginative teenager fabricates fantastic stories, not realizing elements of those stories are manifesting in the home and drawing their father deeper and deeper into the dark world of his id.

Why You Should Read: Some of you may recognize this script from when it was featured last year on AOW. I received many notes that weekend for which I am eternally grateful. I put it away the script for some months and worked on other projects while trying figured out how to address the story with a whole new approach. Needless to say I woke from a dream one night to find none other than Billy Wilder standing at the foot of my bed. Together Billy and I took the story by it’s horns and wrestled it into submission. We even gave it a new title. The sun came up, Billy was gone and The Three Degrees Of Separation was ready for discerning eyes. Love it or hate it, it will leave an impression on you. I think you will love it. But if you hate it, blame it on Billy.

Title: Damn Nation

Genre: Horror/Action Thriller

Logline: Five years after a plague has overrun the United States, turning most of the nation into feral vampiric creatures, a Special Ops unit from the President’s current headquarters in London is sent back into the heart of the US in a desperate attempt to find a group of surviving scientists who claim to have found a cure for the disease… but not everyone wants to see America back on its feet.

Why You Should Read: I believe screenplays are evolving. With the advances of technology in the last couple of decades such as the internet, computers, ipads, smartphones, etc, screenplays can be more than words on paper, they can be visual and even interactive experiences. I’m not the first and I won’t be the last person to integrate artwork into my screenplay, but I think this approach, if done right, can add a lot of value to a project. Integrated artwork is just the tip of the iceberg though. I believe soon people will be adding a lot more elements, such as photo references, storyboards, video, sound effects, music, and other audio-visual components embedded into their scripts. The possibilities are endless.

However, I know that my view on things is going to be vastly unpopular right now. I think most people will have an old school attitude and believe that writers should write, leaving the fancy bells and whistles to someone else.

With that said, I do believe nothing is more important than the words themselves. Above all else, I hope my script is judged on the words, not the images. Everything else I’ve added is just a bonus.

Title: Sarah’s Getting Married

Genre: Comedy

Logline: Harry, wrongfully accused of embezzlement, escapes from prison in order to get to his daughter’s wedding and walk her down the aisle.

Why You Should Read: Concept is king. It’s something we’ve all heard, and I feel this script has a great concept that can really sell. This is an idea that I’ve had for years, and it has gone through many changes. But I finally came up with a good, fun way to tell this story and I want to share it with everyone who is willing to take a look at it. Besides, who doesn’t like a good comedy that has heart?

Title: Lifeline

Genre: Dramedy

Logline: A womanizing dockworker is forced to take in his estranged, brain-injured father after the old guy is ousted from a nursing home.

Why You Should Read: I’ve placed my story in the port city of Halifax, Nova Scotia because I wanted the setting to set the tone of the script and influence the characters. It’s a “relationship” dramedy that’s fun and poignant and has a lot of heart (I hope!) Sorry, no guns, explosions or time travel. I’ll save that for the rewrite!

Title: THE PINSTRIPED PRIMATES

Genre: Family

Logline: Three talking gorillas escape from captivity and enter the world of professional wrestling. The two older brothers – managed by the intellectual younger brother – take a run at the tag-team championship.

Why You Should Read: It’s something different for both of us. For me, it’s a shot at lighter writing. For you, it’s a chance to escape from the usual AOW ghetto of contained thrillers, gross-out comedies, and derivative horror. Have you ever reviewed an amateur Family screenplay? — Also, this script Quarterfinaled in the 2014 Fresh Voices contest. This is intended as live action with latex makeup, like the original Planet Of The Apes – not animation.