Search Results for: F word

I predict today’s writer will be writing movies we see one day. So how come I’m not onboard with this skill-rich script?

Genre: Drama/Coming-of-Age/Comedy

Premise: (from writer) Fatherless Copywriter, Nick Adams, uncovers a stash of immaculate love letters dated the year he was born and post marked from Key West and Havana, Cuba. Convinced he is Hemingway’s bastard love child, he travels to Key West with teenage son in tow to usurp his birthright.

About: This is an amateur script that came referred to me by one of my consultants.

Writer: Eric Brown

Details: 113 pages

Now that we’ve proven there’s undiscovered talent out there just waiting to be found (Patisserie baby!) I’m back on the amateur bandwagon, hoping to bring more scripts to Hollywood’s attention. Hemingway Boy, I’ve been told, has a shot at being one of those scripts. The script was given to one of my consultants for notes and later recommended to me (which doesn’t happen very often).

In the time it’s taken me to finally read and review it on the site, it was picked as one of the coveted “referrals” on The Tracking Board’s site. One person recommending a script can always be a fluke. Two? Means we probably have something good here. And since my taste matches up well with Christian’s (my consultant), I figured Hemingway Boy might be able to bring me to my screenwriting happy place.

40 year old Nick Adams feels trapped. As writer Eric Brown points out, he’s like “all of us” in that respect. You know when you’re a kid and you plot out where you’ll be in 30 years? Yeah, well, Nick’s at the opposite of wherever that is. How opposite? Well, he writes advertising slogans for baby food. And while he gets paid a lot of money for it (he’s even in line for a promotion!), how excited can you get when you’ve won over a target audience who’s not only illiterate, but hasn’t learned their ABCs yet?

In addition to the career stuff, Nick has to take care of a chirpy mother with early onset dementia. He must contain an increasingly rebellious teenage son (Sam). And he must learn to be civil with his irritating ex-wife.

Well at least one of those problems gets solved when Nick’s mom kicks the bucket. But just when he thinks that’ll calm things down, Nick stumbles upon an old box of love letters written to his mom from a mysterious man. After doing a little research, Nick becomes convinced that that man is Ernest Hemingway, and that his Mama Mia’esque mother made him the bastard child of the famous author.

Feeling some purpose for the first time in his life, Nick grabs his son and heads to the town in Florida where Hemingway spent most of his life. He hopes to ask around, find out if anyone saw Hemingway and his mom together, and go from there. When he gets there, he’s greeted by his tour guide Joe Jack, a step-father of sorts who dated Nick’s mother for awhile. Back then he was a pretty selfish prick, and now he wants to make up for that phase in his life by helping Nick however he can.

Once set, Nick meets a bus driver named Charlie (noooo – not the female love interest with the male name!) who he starts to fall for, while Sam ends up meeting a too-cool-for-school hottie named Stacee who he falls madly in love with. We jump back and forth between these relationships as they equal parts sputter and sparkle. With time running out before Nick has to be back in Detroit for work, it’s looking like he’ll never find the truth. That is until he locates an old friend of his mom’s who lives in Cuba. Going there is a risk, but Nick HAS to know. So grabs a boat and endures the final leg of his journey.

Here’s the thing about Hemingway Boy. It’s written by a real writer. It’s not one of those amateur scripts you read and say, “This guy isn’t even ready to be judged because he doesn’t know how to write yet.” Brown knows how to write. He’s very comfortable in this medium. For that reason, I see this more as a professional script than an amateur one. And for that reason, you’re going to judge it like a real movie, not on its mistakes, but rather its choices.

While I can understand why people responded to this, it wasn’t quite my cup of tea. Let me try and explain why. I don’t react well to scripts that are high on quirk. Scripts that feature the kooky grandmother, scripts where billboards are talking to our characters, scripts where every other character is flamboyant or over-the-top. I’m a big believer that the story always comes first. So if I feel that the writer is more interested in coming up with a wacky character than they are pushing the story forward in an interesting way, I start to turn on the script.

I do this because I’m now focused on the writing instead of the reality the writer’s created. In other words, I’m out of the story. And you don’t want your reader to be outside the story thinking about YOU, the writer, writing this. The spell is broken once that happens. And I found myself increasingly reacting to things other than the story.

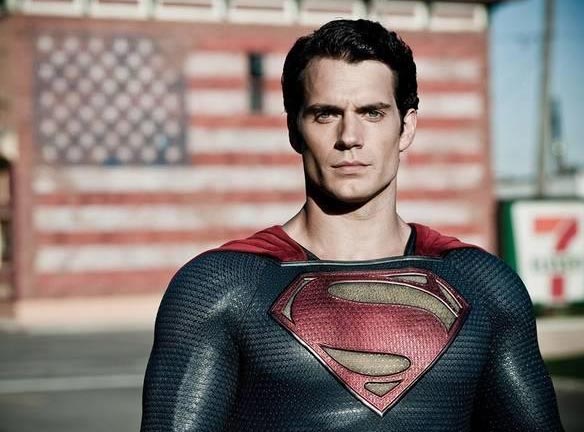

The first moment this happened was Grandma Janice (I say “grandma” if we’re looking at her through Sam’s p.o.v.). As soon as she came in and started acting kooky and quirky, I said, “Uh-oh,” under my breath. I’m not going to lie. I hate the unpredictable “says whatever’s on her mind” grandma character. I see it so much. I think it’s so cliché. It’s kind of like screenwriting kryptonite to me (ahh, I can’t seem to forget Man of Steel!). And I’m not saying you should never write the character. Obviously people respond to it (who doesn’t like Betty White in The Proposal?). But that character kills me so much that when she showed up, I instantly turned on the script.

And if that was all, I might have rebounded. But it felt to me like every character was over the top. For example, Joe Jack, the grandfather character, almost seemed like a male version of Alice. He was big, loud, over-the-top, and always said embarrassing things. So again, we’re favoring quirkiness over reality. And I get that that’s a choice. I’m not saying it doesn’t work. It just doesn’t work for me.

On top of this, I couldn’t pinpoint why exactly Nick wanted to know if Hemingway was his father other than it would’ve been kinda cool. He mentions a couple of times that he just wants to know where he came from, but we seem to be missing out on a potential bigger story here. I wanted to know exactly why Nick needed this answer because it was the question driving the entire story. And if I’m not even sure on why he’s going after it, it’s hard for me to 100% engage in that quest with him.

With all that said, there’s definitely something here. While I didn’t like how extreme the characters were, there was a lot of depth to them. And all of them stood out, which can’t be said about the majority of amateur screenplays out there – which struggle to come up with a single memorable character. That’s a big-time writer skill. I thought the stuff with Sam and Stacee was interesting (although I was hoping he would end up with Stuckey, her younger sister). There’s definitely a goal here (trying to find proof if he’s Hemingway son). There’s some urgency (he’s only got two weeks). There’s plenty of conflict in the scenes, with characters meeting obstacles in whatever goal they’re pursuing. The 3-Act structure is in place.

So it’s clear Eric knows what he’s doing. My preference was just that the script be a little more grounded in reality and less proud of itself. I wanted more people who acted like people as opposed to caricatures of people. That would’ve pulled me in and made me believe in everything more, instead of concentrating so hard on the person writing the script. Then again, the same thing can be said for writers like Tarantino or Shane Black, and they’re doing all right. So maybe I’m just being Grumpy McGrumperbottoms. What did you guys think?

Script link: Hemingway Boy

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me (but this writer shows a lot of promise)

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: I’m a firm believer in the hero going after the goal hard. If he’s not going after the goal hard, that tells me he doesn’t want it that much, and if he doesn’t want it that much, then why should I want it for him? Nick’s actions never matched up with his words. He always felt a bit too casual in his pursuit. I wanted him to be dedicating more time to this endeavor. I wanted to feel more urgency and desperation.

There’s a reason I’m busting out The Dark Knight for this week’s Ten Tips. This weekend I experienced a super-human catastrophe in Man of Steel. And I want to look at an actual well-made superhero film to see how to do it right. What’s interesting here is that two of the major players are the same in both projects (Christopher Nolan and David Goyer). The big flashy addition is Zack Snyder, which tells me that his paws may have been the ones that dirtied up the Man of Steel waters. With that said, I’m not going to pretend like The Dark Knight is some tour de force in screenwriting. I’ve battled many a time with this screenplay and feel that it has just as many weaknesses as it does strengths. With that said, it’s a far superior screenplay to Man of Steel, particularly in the area of character. So let’s see what we can find when we compare the two behemoths. I suspect some some nifty tips!

1) Give us a main character who’s active – It’s one of the simplest and often-stated screenwriting rules there is, and yet us screenwriters constantly forget it, finding ourselves 60 pages into our screenplays and wondering why they’re so boring. One only needs to watch Man of Steel to see how an inactive main character can destroy a movie. It makes them (the main character) bland, which forces the story/plot to work overtime to overcome this issue. That’s likely why we had so much overplotting in Man of Steel. The writers sensed something was wrong but couldn’t figure out what, so they just kept ADDING MORE PLOT. The simplicity of having an active main character is that they forge forward, carving out the story on their terms. Look at Bruce Wayne. The guy wants to make a difference so he creates Batman to do so. He WANTS to fight crime and clean up the streets, so he’s always out there actively pursuing that. Superman in Man of Steel is the opposite.

2) Beware the reluctant protagonist – Building on that, Man of Steel made me take a hard look at the reluctant protagonist. By “reluctant,” I mean a character who’s reluctant to engage in the central conflict of the film. That’s Clark Kent. He’s reluctant to get involved in the world’s problems. A big reason this doesn’t work is because by being “reluctant,” you’re basing the entirety of your hero on a negative trait – avoidance – which pretty much goes against everything that’s fun about movies (our hero ENGAGING in the adventure). There are movies where it works (Michael Corleone in The Godfather) but it usually doesn’t, especially in action movies. The word “reluctant protagonist” now scares me. It should probably scare you too.

3) Just tell us what’s happening dammit – I’ve read a few amateur screenplays recently where the writer tries to do way too much with their action description. They write stuff like, “Sweat glistens off Joe’s knuckles as he wrestles the gun out of his pocket.” There are times where you want to add a little flair to your writing, but for the most part, just tell us what’s happening. Here’s how Jonathan and Christopher Nolan write an early scene before the bank robbery in The Dark Knight: “A man on the corner, back to us, holding a CLOWN MASK. An SUV pulls up. The man gets in, puts on his mask. Inside the car – two other men wearing CLOWN MASKS.” These are two of the top writers in the business and every word in that description is something a third grader would understand.

4) “A&P” (An Active main character with Personality) – The character type who’s typically the most fun to watch is ACTIVE (making his own decisions and pushing the story forward himself) with PERSONALITY (is charming or funny or clever or smart or a combination of all these things). Look no further than one of the most beloved characters of all time, Indiana Jones, to see how that combination works. Or Iron Man. Or Sherlock Holmes. While I wouldn’t say Bruce Wayne is going to open at The Laugh Factory anytime soon, he does have a personality, likes to have fun with his money, and has a sense of humor. Combined with his desire to fight crime (being active), he’s got the coveted A&P. Superman in Man of Steel has neither the A or the P, which is why he’s so forgettable. As a rule, try to have the A and the P for your protag. If you can’t, give him the A or the P. If you can’t give him either, I guarantee you you have a boring protag.

5) Backstory is the enemy – Remember that superhero origin stories are by definition required to show us the backstory that led to our hero becoming who he is. In the real world of spec screenwriting, backstory is the enemy. Unless there’s some really unique or traumatic or shocking thing that happened in our character’s past, don’t show us. And if you do, show us only the bare minimum of it. It can even be boiled down to a quick expositional sentence if you do it right. Batman Begins handled its backstory a lot better than Man of Steel, but in both cases, the main plot (taking down the Scarecrow and Zod respectively) had to be pushed to the second half of the script, something that will never be accepted in the spec arena.

6) Invisible Backstory is your friend – You may not tell us a single thing about your main character’s past, yet you – the WRITER – should know everything that happened to your hero since the day he was born. This knowledge leads to SPECIFICITY OF CHARACTER, a character who is unique because of the extensive “real” life he’s lived in your imagination. The less you know about your hero, the less specificity you’ll be able to infuse him with, which leads to genericness. This is one of the quickest ways I can differentiate the boys from the men in screenwriting.

7) Conflict is your weapon against exposition – One of the earlier scenes in The Dark Knight has Bruce talking to Alfred about needing improvements to the Bat Suit as well as getting info on the new District Attorney (who’s dating Rachel). It’s a straight forward exposition scene and, for that reason, one of the more forgettable of the film. Contrast this with when Bruce meets Harvey Dent (the District Attorney) out for dinner. Harvey’s with the love of Bruce’s life, Rachel, and Bruce has brought along a hot ballerina. There’s a lot of exposition in this scene, mostly in regards to Harvey trying to save the city, but the scene is fun because of the conflict: Wayne sizing up Harvey and the jealousy between Bruce and Rachel. Conflcit is your weapon against exposition. Use it whenever the evil EXPO rears its head (Nolan forgot this simple rule in Inception, which is why so many of his early scenes are boring. They’re pure exposition with zero conflict).

8) Brains over brawn – I think one of the reasons Batman is more popular than Superman is because he can’t just fly away. He can’t just use his heat vision to burn a hole through a guy. He’s gotta use his brains. Granted, he’s got a lot of money and that money has created a lot of gadgets, but Batman’s way more dependent on his wits than his powers. I bring this up because I read so many scripts where the writer gets his hero out of a battle with a gun or a roundhouse kick or a superpower. The thing is, it’s always more rewarding when the hero uses his wits (his INTELLIGENCE) to get out of that situation. So always look to your hero’s mind to solve his problems, first. Only use physical force as a last resort.

9) Have your bad guy earn his keep – Whenever I re-read The Dark Knight, I’m always studying the villain, since the Joker is one of the most famous villains of all time. He’s lasted decades, whereas most villains last the two hours that make up the film (Die Hard With a Vengeance anyone?). Upon reading The Dark Knight, I realized that for truly timeless villains, you gotta like them a little bit. And I think one of the reasons we like watching The Joker is because the guy earned his keep. He wasn’t handed anything. He had to rob a bank and infliterate and intimidate the biggest baddest nastiest dudes in town. As crazy as it sounds, we kind of respect him for that, and it makes us sorta like him. So make your bad guy earn his keep. We’ll respect him (and actually like him) more.

10) Rational vs. Irrational Villains – Something I noticed while comparing The Dark Knight to Man of Steel, is that they have two polar opposite villains. General Zod is rational and calculated and has strong reasoning for doing what he’s doing. The Joker, on the other hand, is irrational and unpredictable and confusing. No doubt The Joker is the much scarier of the two. Through this, I learned the value of bad guys who are a bit unpredictable, a bit out of control. When you think about it, those are the scariest people in life because they don’t have that “rational” button you can push. I was never scared of General Zod cause the guy was just so darn rational.

These are 10 tips from the movies “The Dark Knight” and “Man of Steel.” To get 500 more tips from movies as varied as “Aliens,” “Pulp Fiction,” and “The Hangover,” check out my book, Scriptshadow Secrets, on Amazon!

It doesn’t get much better than Goodfellas, a script based on the non-fiction book “Wiseguy” by Nicholas Pileggi (who shares writing credit with Martin Scorsese on the film). The film came out in 1990 and got nominated for six Academy Awards. Joe Pesci, in a role he’s still getting mileage out of, won for best supporting actor. While the story structure was put in place by the writers, much of the great dialogue was discovered through rehearsals, where Scorsese let his actors roam free, then wrote into the script many of the lines they came up with. While Pileggi wanted to follow a traditional narrative, Scorcese didn’t think it was necessary, believing the film was more a combination of episodes, and those episodes could be told out of order. It’s this and a few other non-traditional choices that make Goodfellas so interesting to study as a screenplay. As the story goes, after reading the book, which Scorsese thought was the best book on the mob ever written, he called Pileggi and said, “I’ve been waiting to direct this book my whole life,” to which Pileggi responded, “I’ve been waiting for this phone call my whole life.”

1) The tragedy script – The tragedy script does not follow the traditional three-act structure (setup, conflict, resolution). It works more in two halves. You build up the hero’s success in the first half, then have them fall apart in the second. That second half fall should be dictated by the hero’s flaw, which can be anything, but is most often greed.

2) The cool thing about tragedies is that you can have your main character do some pretty horrible things – The audience understands this isn’t a romantic comedy. They don’t need their main character to be a saint. They get that bad things are going to happen and that our protagonist is going to be unsavory. Embrace that. I mean, despite all of us falling in love with Henry’s (Ray Liotta) first love, Karen, he starts having an affair with another woman on the side. You can’t do that in a traditional film without the audience turning on the protag. The one caveat to all of this, is that we must START OUT loving our main character. We’ll only go down the dark path with him if we liked him before he got there. So it’s no coincidence that Scorsese and Pileggi used one of the most common tools available to make us fall in love with Henry – they made him an underdog – the little nobody kid from the streets who worked his way up the system.

3) Give ’em something to talk about – What I learned about voice over during Goodfellas (which is used practically non-stop) is that if you have a fascinating subject matter and you’ve researched the hell out of it, the device is a great way to give us all of that information. What sets movies like Goodfellas and, say, Casino apart is those “behind the curtain” details we learn about the subject matter. You walk away knowing exactly what it was like to be a wiseguy (or what it was like working in a Casino) after watching these films. But extensive voice over like this ONLY WORKS if the subject matter is fascinating, if you’ve researched the shit out of it, and if you’re telling us stuff we don’t already know. Break one of those three rules, and the voice over will probably get tiresome.

4) We’re more likely to go along with a character’s suspect choices if we’re inside his head (listening to his voice over) – There’s something about hearing a character’s play-by-play of his life that makes us more tolerant of the terrible things he does. If Henry is robbing people and cheating on people and killing people without him ever telling us why, there’s a good chance we’ll turn on the character. But because he’s explaining it to us as he goes along via voice over, we understand his choices. It’s kind of like hearing that some random person you don’t know is cheating on their spouse. You immediately conclude that they’re a terrible person. But when your best friend cheats on their spouse, and they explain to you why they’re doing it and what went into the choice, you’re more okay with it. Voice-over can be very powerful that way.

5) Research research research – I’ve read a LOT of amateur scripts about the mob over the years and none of them ever come close to Scorsese’s films. Why? Research. Nothing feels original or unique. These writers fail to understand that Scorcese is using material that has been meticulously researched. I mean, authors like Pileggi have spent hundreds of hours talking to the REAL PEOPLE involved in these crime magnets. He’s getting the stories that REALLY happened. Whereas with amateurs, they’re making up stories based on their favorite movies. Therefore they read like badly made copies. So if you’re going to jump into this space, you better have at least a hundred hours of research to base your story on. Or else forget about it.

6) Start your script with a bang – Goodfellas starts with a bang and never lets go. And that got me thinking. In the comments section of the Amateur Offerings post this weekend, a commenter said he stopped reading one of the entries after page one because it was boring. A debate then began on whether the first page of a script should always be exciting. Some believed it should, and others said the writer should be afforded more time. The actual answer to this question is complicated. In the spec world, yes, the first page should immediately grab the reader. However, your first scene should also be dictated by the genre and story. If you’re telling a slow-burn story, for example, then a slower opening makes sense. But the definitive answer probably lies within what happens BEFORE you write the first page. You should choose the type of story that would have an exciting opening page in the first place, since it IS so important to grab that reader from page one. Once you’re established and people will read your scripts no matter what, THEN you can afford to take your time getting into your story.

7) Always look to complicate your scenes – Driving a dead guy into the woods to bury him isn’t a very interesting scene. Driving a “dead guy” who all of a sudden starts banging on the inside of the trunk (Oh no, he’s still alive), is. And it leads to one of the most memorable moments in Goodfellas, when Tommy starts bashing the still-moving bloody mattress cover over and over again. Try not to allow your scenes to move along too smoothly. Always complicate them somehow. It usually results in something more interesting.

8) Beware the mob/gangster screenplay naming conundrum – One of the biggest assumptions young writers make is that readers will remember however many characters they introduce, be it 5 or 500. I can’t stress enough that too many characters leads to character mix-up which leads to story confusion. Mob movies are particularly susceptible to this problem for two reasons. One, they naturally have a lot of characters. And two, most of the character names sound the same, ending in “-y” or “-ie” (Jonny, Billy, Tommy, Frankie) making it particularly easy to mix characters up. For this reason, whenever you write one of these scripts, it is essential that you make everybody memorable and distinctive. Here are a few tips to achieve this (note that these will work for any script with a lot of characters):

a. Only create characters if they’re absolutely essential to the story (less characters equals less of a chance the reader will forget who’s who).

b. Differentiate names as much as possible (don’t use “-y” and “-ie” names if you can avoid it). If you have to do this, consider using a nickname or their last name to identify them by.

c. Describe each character succinctly. No bare-bones “fat and awkward” descriptions.

d. Give each character their own unique quirks. Anything to make them stand out from the other characters.

e. Open up with a memorable character-specific scene for each of your big characters. So if you have a character who has a temper, open up with a unique compelling introductory scene that shows him losing his temper (like how we introduce Tommy in Goodfellas, who gets so mad at Billy for insulting him that he kills him).

9) Bounce around a large location easily by using mini-slugs – A mini-slug is basically a quick identifier of where we are inside a larger location. Since a full slug line indicates a more severe location change, it can ruin the flow of a scene if used often. For example, say two characters are bouncing around multiple rooms in a house. You don’t have to write, “INT. KITCHEN – SECOND FLOOR – DAY” every time you come back to the kitchen. Just say, in capital letters, and on their own line: “THE KITCHEN” or “THE BASEMENT” or “THE LIVING ROOM” or wherever the sub-location might be. These are mini-slugs.

10) The “powder keg” character – To me, these characters always work. If you write a slightly crazy character who could blow up at any second, then any scene you put them is instantly tension-filled. It’s like the character brings with him a floor full of pins and needles wherever he goes. It’s why Tommy DeVito (Joe Pesci) is such a classic character. We’re terrified of what he’s capable of. We’re worried that anyone at any moment could say the wrong thing and BOOM! – our powder keg blows up. If you can find a way to weave a powder keg character into your script (and it fits the story), do it. These characters always bring the goods.

These are 10 tips from the movie “Goodfellas.” To get 500 more of the most helpful screenwriting tips you’ll ever find, mined from movies as varied as “Aliens,” “Pulp Fiction,” and “The Hangover,” check out my book, Scriptshadow Secrets, on Amazon!

These are 10 tips from the movie “Goodfellas.” To get 500 more of the most helpful screenwriting tips you’ll ever find, mined from movies as varied as “Aliens,” “Pulp Fiction,” and “The Hangover,” check out my book, Scriptshadow Secrets, on Amazon!

Whenever I’m not totally 100% sure about something, I write an article about it. It forces me to do what I’m scared to do – explore the subject and find an answer, despite the possibility that that answer might not be found. So it’s scary writing these articles. I mean, what if I can’t figure it out? What if this aspect of writing will always elude me? I can’t have that. I must know everything!

Clichés, in particular, have always baffled me. You’d think it’d be as simple as, “Don’t use cliches,” but it isn’t. I’ve fallen in love with plenty of great movies that others have insisted were riddled with clichés. Many times I have to admit they’re correct, and yet I still love the movie. This implies that there are actually plenty of instances where you want to use clichés. But where, why, and how are never as clear as you’d like them to be. So it’s frustrating.

I guess the first thing we should do is define cliché. The wonderful bastion of knowledge known as “Wikipedia” defines them as, “an expression, idea, or element of an artistic work which has become overused to the point of losing its original meaning, or effect, and even, to the point of being trite or irritating.” Okay, sounds simple enough. But it doesn’t explain how something that’s “overused” to the point of being “irritating” can still work.

I pointed this out in an article awhile back. The ending of Die Hard has Bruce Willis limping up to the bad guy with a gun, who’s holding his wife hostage. It’s the most cliché of cliché situations. And yet I’m riveted. I am riveted by a classic cliché. And I can go back to that scene again and again and still be riveted. I asked the Scriptshadow faithful about this, and while I received a lot of interesting feedback, nobody could definitively tell me why it worked, despite its cliché nature. I’m not sure I’m ever going to find that out. But I can tell you what I do know about clichés and maybe that will get us a little closer to the answer.

1) Cliches are more evident when they’re surrounded by bad writing – This may seem obvious, but it’s something I don’t hear very often. When a plot is cleverly constructed, when characters are deep and compelling, when a strong theme is incorporated and the dialogue is sharp and witty, audiences give you the benefit of the doubt and allow you the occasional cliché. In fact, they probably won’t even notice it because it’s buried inside an otherwise riveting story. But when your plot feels slapped together, your characters are thin, and you seem to be making things up as you go along, clichés pop out like weeds in a rose garden. Construct a meaningful well-thought-out story and clichés feel more like honest choices than clichés.

2) The good and the bad cliche – Cliches have two sub-sets, one negative and one positive. The first subset consists of lazy predictable choices. The second is a commonly used story choice brought back again and again because it’s been found to work. Understanding the fine line between these two sub-sets is often what separates the good writers from the bad. Bad writers use clichés because they’re lazy and don’t want to spend the time coming up with a more original choice. Good writers recognize that they’re about to use a cliché and weigh the options of that versus something more original. They know that if they do choose the cliché, it’s because it works best for that particular moment in the story. Batman and the Joker hanging off a building at the end of The Dark Knight is a pretty cliché choice, but it fit the story, it fit the characters, it felt right for that particular moment, so Nolan went with it. As long as you weigh your options and legitimately feel like the cliché choice is your best way to go, you should be okay.

3) If you explore something honestly, it’s less likely to feel like a cliché – Building on that, clichés feel more like clichés when they’re surface level. If all you’re giving us is a quick and dirty examination of the choice, it will scream “cliché.” On the flip side, they feel less like clichés if you dig into and explore them. Take a common cliché story situation – a son who lives in the shadow of his father, or a son who’s always pining for his father’s approval. We’ve seen this hundreds of times before. However, it’s still a relatable situation to a lot of people, and therefore has the potential to be quite powerful. But you have to explore it honestly. You have to go back and write an entire backstory (to yourself, not in your script) of what happened between these two characters to get them to this point. The more specific you can make it, the more real it will feel on the page, and if something feels real, cliché or not, it will probably work.

4) Archetypes – Character clichés are one of the most abused types of clichés out there. Boy, do I see a lot of cliché characters when I read scripts. And yet, these clichés are practically promoted. Character archetypes (the Jester, the Sage, the Rebel, the Romantic Interest) are taught fairly early on in writing classes. And you see them everywhere (Obi-Wan Kenobi is the Sage. Han Solo is the Rebel). So with these cliché character types being so ubiquitous (and promoted), how are we supposed we make them original? The answer is to always add a twist. It’s okay to write “The Rebel” into your story, but give him a twist that doesn’t exactly fall in line with the cliché. So Rocky Balboa would probably be considered “The Rebel,” but he’s got a little bit of “The Jester” in him. He likes to make jokes. He’s got a sense of humor, something you don’t usually see in other Rebel characters. So always look to add that twist.

5) The more familiar the premise, the more likely the clichés – Remember that the premise is what builds up, holds to together, and ultimately defines your story. So if it’s too familiar, so likely will be the variables within it. In other words, a cliché premise is going to result in a lot of clichés. To that end, you really really really want to come up with an original premise. Look at romantic comedies, for example, one of the most cliché-ridden genres out there. A couple of writers decided to turn that formula on its head and wrote “500 Days Of Summer.” Because we weren’t going down that traditional path, the story choices that presented themselves weren’t traditional. When agents and producers talk about wanting something “fresh,” what they don’t realize they’re asking for is a script devoid of all the clichés they’re used to. And this can be achieved simply by coming up with something unique at the concept stage.

I think, in the end, if you can pull us into your story, if you can make us care for your characters and their predicament, the clichés in your script will fade into the background. They won’t feel like clichés so much as pieces of a story. Having said that, I think that you should always be asking, “Have I seen this in a movie before?” If the answer is “Yes,” or worse, “Yes, I’ve seen it a lot,” then you owe it to yourself to come up with some other options. You might not end up using those options, but you should at least consider them.

Also, whatever cliché you use, whether it be in a premise, a character, a scene, a twist, a line – try to add a new angle to it, even if it’s subtle. That twist is what’s going to obliterate the cliché. So if you have a pirate, don’t make him a big fat cliché jerk, make him funny and goofy and bumbling, like Jack Sparrow.

And finally, recognize that “cliché” is not always a bad word. Familiar story beats and characters keep showing up in movies because they’ve been proven to work. As long as those cliches are the best options available, you should be fine. Now whether this answers the question of why that scene with Bruce Willis at the end of Die Hard works, I don’t know, but I think it’s a good start to figuring it out. What about you guys? What’s your take on clichés? Why do you think they work sometimes and don’t work other times?

Refn and Gosling’s new flick got booed at Cannes. Let’s see how the screenplay fared.

Genre: Drama

Premise: A British man living in Bangkok goes after the man responsible for killing his brother.

About: This is the reteaming effort of Nicolas Winding Refn and Ryan Gosling, who of course worked together on Drive. The big difference here is that Refn also wrote the script. The film just debuted at Cannes, where the crowd heavily booed it during the credits. Refn responded by saying that good films divide and challenge audiences, so he was okay with the booing. Either way, I wanted to read this screenplay.

Writer: Nicolas Winding Refn

Details: 97 pages – 2nd draft

I’m not totally sure what to make of Nicolas Winding Refn yet. I loved the original Drive script, but he totally gutted it. Yet somehow the gutted version was just as good if not better than the original version. When I listen to his interviews, he sounds equal parts humble and full of himself. There are records of him breaking down and crying in cars in order to find the truth to his movies. Speaking to some people in the industry who have worked with him, he’s been described as an egomaniac crazy person on par with Amanda Bynes.

I guess none of that really matters though. What matters is the end product. And according to the French, the end product was pretty bad. And 999,999 times out of a million, you can trace back what’s wrong with a movie to the script. So I busted open Only God Forgives and started reading. I don’t know if I’d call this story boo-worthy so much as bore-worthy. It’s just not a very interesting narrative. I get the feeling Refn wanted to explore the depravity and dark alleys of Bangkok, and maybe focused more on that then actually writing a good script. Let’s take a look.

Only God Forgives follows 30-something Julian, a Brit (I’m assuming) living in Bangkok as (I think) a bookie for underground fights. The gist is, he lives a shady life. But not as shady as his brother Billy, who’s pretty much doing the same thing without the work ethic. After a fight, Billy goes out into the city, finds an underage hooker, has sex with her, then beats her and kills her. Oh yeah, this movie is not for the faint of heart.

In comes lead detective Chang, who carries with him an almost otherworldly presence. Chang finds the dead hooker’s father, yells at him for allowing this to happen, then tells him to go kill Billy. So the father walks in and beats Billy to a pulp, killing him. Yes, lots of killing in this movie. The detective then chops off the father’s arm for being a bad father.

Julian eventually finds out his brother was killed and goes after the killer, in this case the father, but when he finds him, he can’t seem to kill him. Eventually, Julian’s mother shows up, who throws the word “cunt” around like you and I do “screenplay.” She wants revenge on this father, so she puts a hit out on him.

Eventually, they learn that the father wasn’t really the bad guy here – it was Chang, who’s rumored in these parts to be the “Angel of Vengeance,” the man responsible for instituting karma (or something like that). For whatever reason, this title seems to affect Julian, who wants to fight Chang, as both of them were former fighters. Julian’s mother asks, as do we, “What the fuck do you think that will accomplish?” and Julian answers something to the effect of, “you wouldn’t understand,” which we, of course, do not either.

This eventually results in more violence, as at one point Julian blows Chang’s wife’s head off at point-blank range. I’m beginning to understand why this movie was booed. It’s violence on top of violence on top of depravity on top of depravity for no apparent reason. I mean, if the story dictates that violence and depravity need to happen, it works. But when there’s no story, it seems like you’re just exploiting it and that’s the quickest way to have an audience turn on you.

I always come back to the story. What’s the goal here? What are the stakes? Where’s the urgency? Only God Forgives has a goal, but it’s a flawed one. It’s for Julian to find out who killed his brother and get revenge. Here’s the problem though. The brother had sex with an underage hooker then beat her to death. Ummmm, why would we want to see a person like that avenged? We, of course, do not. So the story is flawed from the get-go.

Then the story shifts to this weird undefined showdown between Julian and Chang. I never quite understood it, but Chang is apparently this Angel of Vengeance, which is supposed to mean something, but I’m not really sure what. And I didn’t understand what Julian received by fighting him. At a certain point, even Julian realizes his brother is a low-life, so I don’t get why he’s even trying to avenge him anymore.

To make things even more bizarre, a quarter of the movie is dedicated to Chang singing Johnny Cash at a karaoke bar. It’s just all so strange. Here is this ruthless Angel of Vengenace who chops people’s limbs off, and he’s obsessed with karaoke. Sometimes that contrast can be cool, but here it just felt random, probably because the rest of the script felt random as well.

On top of all this violence and revenge, there are just a lot of bad people in this movie. The mother, in particular, is a really nasty person. When Julian tries to introduce his new girlfriend, she continually calls her a cunt and a prostitute. It’s just this constant barrage of humanity at its worst, and I’m not sure people want to watch that.

I remember writing a script a long time ago, and something about it wasn’t clicking and I couldn’t figure out what it was. I eventually realized that there was no hope in the script. Every character was evil. And if you don’t have some sense of hope, it’s hard to get on board. I mean, does an audience or reader want to be beat over the head with the message, “Everyone is terrible. Life is a meaningless exercise of human beings at their worst”? I don’t think so. Julian is our best shot at a “likable” character, but even he’s banging young hookers and blowing wives’ heads off. I’m all for the anti-hero, but at some point, you’ve gone too far.

If I were giving Refn notes, which I’m sure he’s glad I’m not – but if I were, I would’ve changed Billy from a brother who beats the hell out of underage hookers to a sister or a girlfriend. Now we have an innocent sister killed instead of a deadbeat brother. Already we’re waaaaaay more interested in Julian getting revenge. Sure, it’s more traditional, but I’ll take a traditional storyline that works over an non-traditional one that doesn’t any day.

Refn seems to want to settle this score in the ring, and as it stands, I didn’t even know Julian used to be a former fighter or that Chang had been as well, so when they decided to settle things with a fight, I was confused. So change Chang from a cop into a fighter. He’s an underground kingpin with several layers of security, and therefore Julian knows the only chance he’s got at killing this guy is in the ring. So he’s got to fight his way up the ladder to get a shot at him. I know, I know. This is starting to sound like a Bloodsport sequel, so maybe you tweak a few things here and there to keep the story fresh. But if Refn wants these guys to fight in a ring, that scenario makes a lot more sense than a guy we don’t even know is a fighter fighting a cop in the ring one night. Plot points kinda need to make sense.

In the end, this is just a really ugly look at a bunch of ugly people. And maybe that’s what Refn wanted. He is where he is because he takes chances and he does things differently. But he may have gone too far in this case. Drive was a good story with a set of clear goals and motivations for everyone involved. I didn’t see that here. This was a mess from the get-go.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: When you’re writing about a revenge or a kidnapping, pay close attention to who’s being killed or kidnapped. If this person is unlikable, cruel, a blowhard, a murderer, we won’t want to see them avenged. But if they’re helpless, innocent, and good, we most certainly will. Hence why it’s almost always a better choice to go with a woman/girl/child getting killed than a man. And why it’s a nice idea to make them a good person. Only God Forgives really could have used that.