Search Results for: F word

The current rule-bending king – Malick.

The current rule-bending king – Malick.

Art.

The essence of purity. It should be intrinsic, effortless, natural. A poem. A painting. A short story. All of it should emerge from that illogical, dreamer part of the brain. Write down whatever exists within the deepest recesses of your mind and then (and only then) have you been true to your artistic self. Containing it, rearranging it– sticking with the common word, scenario, characters, etcetera, with which a viewer or reader is all the more familiar, and you are no longer an artist. You are a machine, bottling up art into a series of rules.

It’s a debate that’s been going on way before screenwriting. Should there be “rules” or “guidelines” to art? To me, the answer is obvious. It is a resounding “yes.” But to many, the belief is that you’re defeating the purpose of art if you’re trying to structure it. You’re restraining that part of yourself that expresses creativity. There should be no filter on our imagination. It should exist unimpeded.

Here’s the way I see it. Let’s say you have two writers. One of these writers has been told to keep his scenes under three pages and to focus mainly on pushing the story forward with each one. The other writer has been given no restrictions whatsoever. Have your scenes last as long as you want them to. Focus on whatever you think up at the time, regardless of the story. All else being equal, the focused writer is going to write a better script. It’s rules (or “guidelines”) like this that make us better writers, which results in better screenplays. Therefore, rules are an essential component to art.

Here’s the catch, though: I think every script should break the rules in some significant way. That’s what makes a script unique – its deviation from the norm. Look at Pulp Fiction. It’s a story told out of order and many of the scenes are ten minutes long. Those two “rule-breakers” are what made Pulp Fiction feel so unique. BUT it doesn’t mean Tarantino wasn’t following ANY rules. For example, he made sure each and every scene was packed with conflict so it could sustain a ten-minute running time. “Conflict” is one of the “rules” many consider essential to writing a good screenplay.

The idea here is that you want some semblance of structure to dictate your story, but you pick two or three areas where you go against the mold, where you do things you’re “not supposed to do.” This is what’ll set your script apart. And it’s essential. Because if you write a movie where you follow every single rule to the T, you get a safe “by-the-numbers,” generic screenplay.

It should also be noted that the places where you break the rules will likely be what either makes or breaks your screenplay. Whenever you break a rule, you swim off into unchartered waters. You’re doing something that isn’t usually done. And since there’s no blueprint for the less-traveled path, you’re usually on your own, figuring things out as you go along. Breaking these rules then becomes a huge gamble. And the more rules or the bigger the rule you break, the greater the gamble is. It’s the equivalent of putting all your money into that young up-and-coming company. It can either tank, resulting in you losing everything, or succeed, turning you into a millionaire. You just don’t know until you hand the script to someone else.

With that in mind, here’s what I hope will be a helpful guide to breaking the rules with your screenplay. These are seven of the more common rule-breaking approaches and how to make them work for you:

1) The No-Holds-Barred – This is probably the most dangerous path you can take as a screenwriter. You go into the writing with only the barest sense of what you’re going to write about. There is no plan, no outline. You just feel like writing about something and you let your imagination take you wherever it wants to go. It’s the “David Lynch” approach, if you will. Note that these are typically the worst scripts that I read (by far), and that the only real people who succeed at using this method are also directing the film (like Lynch). I’d strongly advise against this path. Then again, it usually results in the most original material.

2) Out of order – This is one of the more common forms of breaking the rules, and therefore there’s some precedent for how to make it work. You simply tell your story out of order. Movies like Pulp Fiction, 500 Days Of Summer and Eternal Sunshine Of The Spotless Mind succeeded quite well with this device. All I’ll say is if you tell your story out of order, make sure there’s a reason for it. If you do it just to be different, it will show. What was so genius about 500 Days of Summer was that it showed you the greatest and worst moments of a relationship crammed up against each other, something we never get to see in a romantic comedy or love story. So there was a purpose to the choice. I can tell pretty early when there’s no reason for a writer to be jumping around in time in his script. They’re just doing it to be edgy or, they hope, original. But it often ends up feeling so random that I check out before the script is over.

3) Multiple protagonists – You’ve seen multiple protagonists in movies like Crash and Breakfast Club. The reason you should avoid multiple protagonists if possible is because audiences like to identify with and follow a single hero in a story. Once you have two people (or three, or four) to follow, you start losing that close connection that’s required to get sucked into a movie because your interest is being pulled in too many directions. The exception here, and the way to make this work, is to sculpt amazing characters. Each character should have their own goals, dreams, flaws, fears, compelling backstory, quirks, secrets, surprises. If you can make each one of these characters deep enough so that they could theoretically carry their own movie, you can get away with a multiple protagonist story.

4) No Goal – To me, one of the biggest rules you can break, and one that almost always spins the story out of control, is not having a goal for your main character. Without a goal, your main character won’t be going after anything, which means he won’t be active, which means the story will feel like it doesn’t have a purpose. One of the most famous movies to do this is The Shawshank Redemption. Our hero, Andy, is just existing. He’s just trying to make it through life in jail. I believe the key to making these movies work is conflict. You gotta have a lot of conflict. Andy is attacked repeatedly by the rapist, Boggs. He’s thrown in the hole for playing music. His one witness who can free him is murdered. And there is the constant fear that the dictatorish warden and his corrupt officers will take you down if you step out of line. You have to be tough on the protag, make him feel the pain of life, and we’ll watch to see how he deals with it.

5) The anti-hero – Most people will tell you your hero should be likable. And for the most part, I agree. If we’re rooting for your hero, we’ll be invested in whatever story you tell us, whether that story is big, small, slow or fast. But there are a few dozen movies out there with anti-heroes as the lead that have done really well. You have Travis Bickle from Taxi Driver, Lester Burnham from American Beauty, or Riddick from Pitch Black. In my opinion, the way to make these characters work is to a) make them dangerous and b) don’t hold back. You feel at any moment that Bickle might fucking go ballistic and rip your head off. Or with Riddick, the guy is a serial killer. If we’re a little bit scared of these people, we’ll be fascinated by them, and we’ll want to know what they’re going to do next, which is the key to getting a reader to turn the pages. Also, don’t hold back. You have to take some chances with these characters or else what’s the point of writing an anti-hero? Lester Burnham is trying to nail his 16 year old daughter’s best friend. That’s a HUGE chance, and it’s one of the reasons this movie remains so memorable – it didn’t hold back.

6) The long script – It’s one of the most “set-in-stone” rules there is in spec screenwriting: Don’t write more than 120 pages. Yet there are plenty of great, long movies out there. So, how does one get away with breaking this rule? I know this is going to sound like a cop-out but the truth is: great writing. The longer your screenplay is, the better the writer you have to be. Because remember, it’s hard enough to keep a reader’s interest for FIVE pages. Look back at Shorts Week if you don’t believe me. So each additional page you write, you’re increasing the chances that the reader is going to lose interest. In my experience, the long scripts that do well, such as Titanic or Braveheart, show skill in character development, dramatic irony, scene-writing, a keen sense of drama, knowing when to up the stakes or add a twist, theme, conflict, dialogue, you name it. They’re usually INCREDIBLY STRONG at 90% of these things, which is what allows the writers to write something both long and good. A lot of writers (especially beginner writers) BELIEVE they can make a 180 page script work, despite barely understanding any of these things. I (and fellow readers) are the unfortunate recipients of these delusions of grandeur. They are never ever good. So my advice to you would be: Don’t write a long script unless a) you’ve already written 10 full screenplays and b) you’ve found some level of success with your work (some sort of proof that you can tell a good story – a sale, an option from a major company, a win in one of the major contests, etc).

7) The Act-less script – A close cousin to the “No-Holds Barred” and the “No Goal,” the act-less script shuns traditional 3-Act structure in favor of letting the characters and one’s mind take the story wherever it will go. Terrance Malick movies are well known for this, and to a lesser degree, Sophia Coppola’s (watch “Somewhere” to see what a truly act-less script looks like). It should be noted that the 3-Act structure is built on the idea of a hero with a goal, as the first act establishes that goal, the second act is about him pursuing it, and the third act is either him succeeding or failing. So if you don’t have a character with a goal, you’re more likely to run into an act-less screenplay. If you’re going to shun traditional act-breaks, it’s important, in my opinion, that you ask a lot of dramatic questions and include your share of mysteries in the story. Since we’ll want these questions and mysteries answered, we won’t be as concerned with the lack of a traditional setup and strange story direction. 2001: A Space Odyssey shuns traditional structure, but it finds a substitute for that structure to keep our interest in the mystery of the monolith.

The above is a look at some of the bigger rules you can break, but they are by no means the only rules. There are lots of smaller rules to play with like stakes, urgency and conflict. I mean, we’re taught early on in this craft to never come into a scene too early. Well, you can obviously break that rule and come in a lot earlier if it fits what you’re trying to do with the scene. The message I want to get across is that you should break these rules from a place of knowledge and a place of purpose. Understand the rule you’re breaking and have a reason for wanting to break it (which means studying screenwriting as much as possible). Memento is a great example. It’s about a guy who keeps forgetting. Well, if we tell that story in order, then we know way more than our character knows. Tell it backwards (break the rule) and we know just as little as him, which is an approach that fits our main character way better.

Yes, you can go with your gut and make choices knowing nothing about how storytelling works and become that lucky 1 in a million shot that creates something genius. But it’s more likely that the opposite will happen. In my experience, the people who have written these amazing rule-bending screenplays have been in the business for a long time, guys like Alan Ball and Paul Haggis and Charlie Kaufman. Tarantino came out of nowhere, but he’s like the exception to the exception to the exception (and it should be noted he’d seen just about every movie ever made before writing Pulp). I think as long as you’re being true to your own unique voice, to the way you (and only you) see the world, you can still write a script that largely follows the rules and it’ll still come off as original. But you definitely want to break SOME rules along the way. How you do so will largely determine the way your script stands out from the rest.

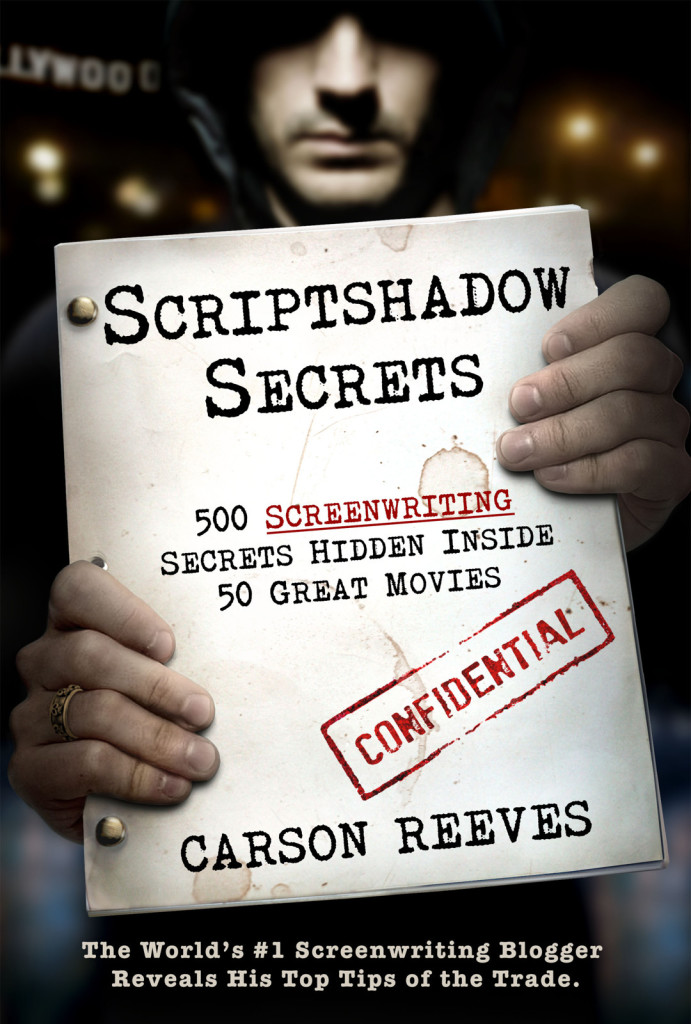

Hey guys. In celebration of, well, all of us being alive, I’m making Scriptshadow Secrets just $4.99 through the weekend! Many of you have asked when the book is coming out in hardcopy. It will, I promise. I just have to carve out some time and get it done. In the meantime, remember, you DO NOT have to have a Kindle device or an Ipad to read the book. You can download, for free, the Kindle for PC (or Mac) app, and use that to read the book right on your computer.

Get Scriptshadow Secrets for $4.99 NOW!!!

Note: Stores outside the U.S. may have a slight delay in the updated price. But it should show up soon.

Remember a couple of years ago when every other spec was a contained thriller? Well, believe it or not, the sub-genre got its start a lot earlier than that. In fact, author Stephen King loved writing contained thrillers, with Misery being his most famous. The movie is the result of three artists at the top of their game. Rob Reiner (who directed the film) had just kicked ass with another King adaptation, Stand By Me. King’s books were being adapted every other day in Hollywood, including the recent hit, The Running Man. And Goldman had just come off The Princess Bride. Misery is built on an old writing adage – Place your hero in the worst situation possible, then watch them try to get out of it. It also operates on the notion that you want to torture your main character as much as possible. Some would argue that King went a little too far in that capacity, but it’s hard to argue with the end result. Misery is also a study in how to write a great character, as Annie Wilkes (played by Kathy Bates – who won an Oscar for the role) is one of the most unforgettable villains of all time. It should also be noted that I could TOTALLY see one of these middle-aged Twilight moms doing this to Stephanie Meyer today. So we may get a Misery re-imagining soon!

1) When you write a movie that takes place in a contained area, the most important tools at your disposal are suspense and conflict. – In a contained thriller, you must continuously imply that something bad is going to happen (which is typically done in the first act), and almost every scene after the first act should be steeped in some sort of conflict. Annie being angry at Paul for writing a bad chapter (conflict), Annie telling Paul he needs to burn his manuscript when he doesn’t want to (conflict), Paul telling Annie his new writing setup isn’t good enough (conflict). Conflict and suspense. Suspense and conflict. They are your saviors in contained thrillers.

2) The most interesting battle is often the battle within a character – We were talking about this yesterday with Gatsby and I think it’s important to note here as well, as we see it with Annie. Conflict WITHIN a character often leads to most entertaining type of character. Annie is both loving and kind, but also manipulative and hateful. She wants to be good, thinks of herself as good, but is in fact a monster. Watching her battle this is both fascinating and horrifying. We’ve seen this with Darth Vader, Michael Corleone, Bruce Banner. It’s why Dr. Jeckyll and Mr. Hyde still survive as one of the most memorable characters in literary history. The more intense the conflict is within one’s self, the more interesting the character tends to be.

3) Try to write career-making roles – When you read Misery, you just KNOW that whoever plays Annie – it’s going to change her life forever (as it did for Kathy Bates!). That’s how complicated and interesting and unexpected and crazy and scary and challenging the character is. You would’ve seen the same thing for Hans while reading Inglorious Basterds, or Ferris while reading Ferris Bueller’s Day Off. Look at your script. Are there any career-making roles in there for actors? If not, maybe reevaluate your script and see if you can do something more compelling with at least one of those key characters.

4) The more you set up a scene, the more powerful that scene will be – For a scene to really pack a punch, it needs high stakes. And high stakes only come through repeated set-ups. One of the best scenes in Misery is when Paul plans to poison Annie with the powder from all the pain pills he’s saved. We watch him meticulously hide and hoard these pills over time. This way, when he invites Annie to dinner and secretly poisons her wine – there’s SO MUCH riding on the moment because we know how much effort Paul’s put into this. It’s also why, of course, when she accidentally spills the wine, we’re devastated. There was SO much on the line since it took him SO long to save those pills. This scene does not work if there’s no setup, if we don’t’ see Paul hiding those pills over time. Continuous set-up results in higher stakes results in bigger more intense scenes.

5) When you’re stuck in a room with a lot of dialogue, you have to look for ways to change things up so the dialogue remains interesting. – Too many writers don’t put enough energy into thinking how they can change the feel or tone or undercurrent of a scene. Note the scene near the 30 minute mark where Paul has to pee in a bedpan while talking with Annie. It’s embarrassing and weird, but most importantly, it gives the dialogue a different twist. There’s a different undercurrent to their conversation because of the awkwardness. This is SO important when you have a bunch of talky scenes in a single location. Keep changing up the feel in the room!

6) Go the opposite to be scary – The scariest things usually aren’t obvious and in your face. They’re reserved or the opposite of what you’d expect. Instead of someone screaming at you, it might be that they talk very quietly and rationally. Instead of someone beating you up, it might be that they’re overly, almost oddly, kind to you. We see this with Annie in her language. She doesn’t believe in swearing, so that when she’s upset, her rants are almost comical. But it’s that lack of the obvious that actually makes these rants so scary. “I thought you were good, Paul, but you’re not good, you’re just another lying old dirty birdie and I don’t think I better be around you for awhile.” Had Annie yelled instead, “Fuck you you asshole. I fucking hate you!” It just wouldn’t have had the same eerie effect.

7) No choice in your script should be random – Every choice you make in your story, there should be a reason behind it, right down to the smallest detail. Take what Annie does whenever she’s outside of Paul’s room, for instance. She watches her favorite show: “Love Connection.” That’s no coincidence, as this theme of Annie being in love with Paul is established throughout Misery. Had she been a huge fan of, say, the sitcom “Taxi,” it wouldn’t have fit into the story as nicely.

8) If you jump into your story right away, your “first act break” has to work like a mid-point. – Typically, in a regular story, the first act break is when the hero begins his journey (like Luke, in Star Wars). But in Misery, Paul is captured by page 5, and has been kept in this room for 20-25 pages already. If you continue on with this setup without any significant changes, the audience will get bored. So you almost use your first act break as a mid-point, as a way to twist the story, up the stakes, and set us off in a new direction. That occurs here when Annie finds out Paul killed her favorite character, Misery. She freaks out and threatens Paul, letting him know that she’s controlling this show and he’s her fucking slave from this point forward (note: you will still use a REAL mid-point break later as well).

9) Most heroes should come into a story trying to make some sort of change in their lives – Change is what makes characters and stories interesting. If all anybody’s trying to do is live the exact same life and do the exact same things they’ve always done, how interesting is that going to be? Therefore, Paul isn’t working on Misery 11 when we start the story. He’s just written his first non-Misery novel in a decade. It’s a huge risk for him, a big CHANGE in his life. And it’s what makes his character more interesting than if he was just trying to do the same old boring thing.

10) Each scene must push the story forward, not repeat the story. – A big mistake I see in these kinds of scripts is that each successive scene isn’t really different from the previous one. For example, a bad writer would have Annie be mean in one scene, and the next time she comes around, she’s mean again. Maybe mean about something else, but still mean. In other words, you’re not evolving the story. You’re repeating yourself. Instead, every time Annie comes in the room, she should have a new agenda, a new goal. First it’s to meet her favorite writer. Then it’s to ask about his new book. Then it’s to talk about her dislike of the new book. Then it’s to introduce her best friend (a pig). Then it’s to yell at him for killing off Misery. Then it’s to have him burn his manuscript. It is SO EASY to repeat scenes in contained thrillers because of the limited location. Don’t fall into this trap. Do something new with each scene.

These are 10 tips from the movie “Misery.” To get 500 more tips from movies as varied as “Aliens,” “Pulp Fiction,” and “The Hangover,” check out my book, Scriptshadow Secrets, on Amazon!

These are 10 tips from the movie “Misery.” To get 500 more tips from movies as varied as “Aliens,” “Pulp Fiction,” and “The Hangover,” check out my book, Scriptshadow Secrets, on Amazon!

David Fincher swoops down to explore his next potential directing assignment. So I decided to check out the book.

Genre: Thriller

Premise: Told from two different points of view, a man’s wife goes missing and he becomes the prime suspect.

About: 41 year old Gillian Flynn is a former Entertainment Weekly TV critic. She’s written three novels, with “Gone Girl” being her most recent. The bestseller got a bump a few months back when David Fincher expressed interest in adapting the book into a film. It’s unclear if he was just circling it or is now officially developing the screenplay.

Writer: Gillian Flynn

Details: Way more than 120 pages long

Why the hell am I reviewing a book? Well, first of all, to prove that I can read books! There’s this rumor going around that I can only read text in courier 12 point font, and that said font can never eclipse 4 lines of continuous text at a time. There have been stretches in my life where this is true. But when someone like David Fincher comes along and says he likes something, my book-reading juices start flowing. And this juice is not made from concentrate.

I can’t remember a single project Fincher’s been attached to that has been bad. Most of the time the script for the project is at least a [xx] worth the read and usually an [x] impressive. What I love about Fincher is that he’s one of the few guys out there willing to take chances. While directors like Jon Favreau and Ridley Scott are pretty much playing it safe, Fincher always wants to push the envelope. Gone Girl is no different. This book is a freaking wild ride. It does stuff I’ve never seen in a novel before.

However, let me warn you, this book is one giant spoiler. There’s a shit load going on and it has one of the best twists I’ve ever seen in a novel or movie. If you have any interest in reading this book or seeing this movie, do not read this review, because I’m going to get into all the spoilers. You’ve been warned.

The first 40 or so pages of Gone Girl are pretty boring. In them, we meet Nick and Amy Dunne, former Manhattanites who have to relocate to Nick’s home town in Missouri when he loses his job. Nick has since used Amy’s money (that comes from her wealthy parents, authors who made a fortune writing books about her childhood) to open a bar that only barely breaks even, and is one of several factors that have driven these two lovebirds apart.

You see, Nick and Amy used to really love each other. Like “love has no boundaries” love. The kind of love Double Rainbow guy would have for a Triple Rainbow. We know this because interspersed between Nick’s present, is Amy’s past, told in firsthand through her journal entries. It’s a devastating dichotomy as we cut back and forth between the wonderful love story Amy offers up and the cold clinical realization of their relationship now, told through Nick’s POV.

Just as we’re getting to know these two, something unthinkable happens. Someone breaks into Nick’s house while he’s away and takes Amy. The crime scene is violent and bloody and while there’s certainly a chance Amy’s still alive, it doesn’t look good. What also isn’t looking good is Nick. You see, Nick fell out of love with his wife a long time ago. And even though she’s been taken, there’s something deep inside of him that doesn’t really care. And therein lies the problem. When Nick goes on national TV to ask for his wife back, there isn’t a shred of emotion in his voice. To any and everyone who watches Nick, they have no doubt that he killed her.

Nick looks for solace from his twin sister, Go. She’s the only one who believes him. But even that’s looking shaky as Nick can’t give the cops an alibi for the time his wife was taken. The book then keeps cutting back and forth between Nick’s worsening nightmare and Amy’s love-sick journal. However, as the story continues, and the journal’s timeline catches up to the present day, we see that Nick has been hiding some secrets. He’s got some demons. And those demons are so bad that as early as last week, Amy went to buy a gun to protect herself from him. It’s looking really bad for Nick. Even we’re wondering if he did it.

And then comes the twist of all twists.

It was a lie. Every word we heard in Amy’s diary was a lie, right down to the personality we thought we knew for the last 250 pages. Amy isn’t bubbly and sweet and good and caring. She’s evil. She’s the definition of hate and bitterness. The diary was a plant, something she’d been working on for a year to lead up to this moment to work as the smoking gun that would send her husband to the chair for her murder. Why would anybody do something like this? For that you’ll have to read the novel. But let’s just say that Amy is the single most vindictive person on the planet.

Once we realize we’ve been scammed, we realign ourselves with Nick, hoping against hope that he can find Amy to prove he didn’t kill her. This task is getting harder by the second as Amy leaks sordid details of Nick’s past anonymously to the press, which means that the cops are probably going to pounce and arrest him soon. Only time will tell how or if Nick will get out of this. If he doesn’t find out how his girl got gone, he’s going to be gone himself.

Okay, I just have to say it. The twist here fucking ROCKED. I mean I was blown away. For 250 pages, we’re given a person, a backstory, a personality, someone we like and trust. We love Amy. To see the “mid-point twist,” then, where we realize it was all a setup? That she made up this version of herself and was really the complete opposite? It’d be like if your best friend of 20 years showed up one day and revealed that he was a completely different person. The way that twisted the story, realigned our sympathy, reversed the polarity of who we were rooting for? It was nothing short of genius.

And really, that’s where a lot of the genius occurs here – the way Flynn frustrates us with who we’re supposed to root for. She makes us hate Nick and love Amy at the outset. Then she shows us Nick’s point of view, and we like Nick and hate Amy. Then we find out something about Nick, and we hate him again, falling back in love with Amy. This constant “switching of allegiances” was masterful, and something we just don’t see in movies, probably because we don’t have enough time. Being yanked back and forth between these two is a big reason this book was able to stay so interesting for so long.

Also, Flynn does an amazing job keeping you guessing who the killer may be. At different points we wonder if Nick himself did it. If an old friend of Amy’s did it. If someone from town did it. At one point we even wonder if Nick’s twin sister is secretly in love with him and killed Amy to get her out of the picture. Flynn is really good at making you think you have things figured out, only to pull the rug out from under you.

What makes Gone Girl so difficult to read though, is that it destroys all hope you have in humanity and relationships. Amy is a vindictive bitch who will go so far as to stage her own murder to take down her husband. And Nick just doesn’t care about Amy anymore. These were two people who were madly in love. So to watch them become these hateful human beings, to see the severity of their relationship’s collapse, kind of makes you want to slit your wrists. It’s really depressing!

But despite snagging an elusive [xx] genius rating through the first half of the story, Gone Girl completely falls apart in its final act. Embarrassingly so. Running out of money and options to survive, Amy comes back to Nick. Amidst all the news coverage and the circus surrounding her disappearance, she just starts living with him again. Amy points out that because they’ve gone through what they’ve gone through, they can’t possibly be with anyone else. They may be miserable, but they’re stuck with each other. And that’s how the book ends, with both of these miserable people deciding to stay together and hate each other til the day they die.

WHAT???

I was so upset with this ending that I went online and researched Flynn to figure out why she would do such a thing. What I found made everything clear. Flynn, it turns out, doesn’t outline. She just writes whatever comes to her. WELL JESUS! NOW IT MAKES SENSE! She wrote a bunch of crazy shit then had no idea how to pay it off. This is EXACTLY how the last act felt. Like someone who had no idea how to end their story.

Which begs the question: How the hell does Fincher plan to adapt this? Why would you adapt something if the greatest thing about it is un-adaptable? We’re fooled by a journal, by a character writing directly to us, who it turns out is lying to us. How does one pull that off in a movie? We have to see Amy. We must show her writing these entries. And since her writing is a façade, something she’s making up, one would presume we’d pick up on her deception as it’s happening.

I suppose you could tell the first half in Amy’s voice over, with her journal entries read out loud over the life she’s describing, but I’m just not sure that would be as convincing (or even make sense). If they do decide to make this, though, I’d look into making the genius twist the ending, as opposed to the mid-point. You don’t really have time to go through an entire relationship and then an entire aftermath of the twist anyway, in a film. This way you’d also eliminate that dreadful ending. That would be really cool if they figured it out, but it will be a challenge.

What an unforgettable reading experience “Gone Girl” was. It has amazing highs and devastating lows. It has “holy shit” twists and an indefensible climax. It’s such an imperfect piece of art, it’s hard to categorize. But I’m not surprised Fincher became interested. It’s so dark and different. If there’s anyone who can figure it out, it’s probably him.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Know your ending before you start your story, if possible. You can come up with all the cool twists and turns in the world, but if you can’t bring everything together in the end, it won’t matter.

Ben Stiller may be pulling in 15 million a movie these days. But there was a time when he was struggling to make a name for himself. In fact, Stiller had been in a string of commercially unsuccessful movies and TV shows, only recently making a name for himself in 1998 with “There’s Something About Marry.” “Meet the Parents,” then, established him as a legitimate comedic force. Now what most people don’t know, is that “Meet The Parents” is actually a remake of a 70+ minute indie film from 1992 that nobody saw. It starred, of all people, Emo Phillips, that bizarre guy with the extreme bowl cut who was famous for like 56 minutes. The film played the festival circuit and actually earned a few fans from critics. Universal reluctantly optioned the remake rights and only after Jim Carrey and Steven Spielberg showed interest (isn’t it Spielberg’s job to show interest in everything at least once?) did the studio really start to push it, eventually casting, of course, Ben Stiller and Robert DeNiro. Another little known factoid is that DeNiro came up with the famous lie detector test scene all on his own.

1) Set up the stakes for your main character before the journey begins – One of the reasons Meet The Parents works so well is because it establishes the stakes for Greg (Ben Stiller) right away. We see Greg trying out his proposal on one of his patients. We then see him go through an elaborate failed proposal to his girlfriend, Pam. Through these scenes, we see that getting this girl’s hand means everything to him (high stakes!). If we don’t know how much achieving the goal means to our character, we won’t care if he achieves it or not. So establish those stakes!

2) Once you establish the goal, you can introduce the main obstacle – The goal here is Greg trying to win Pam’s hand in marriage. Now obviously, if your character succeeds in achieving his goal, your movie is over. So before they can achieve it, you must hurry and introduce the main obstacle. The obstacle in this case is Pam’s father, Jack. Pam makes it clear that she can’t marry anyone her father doesn’t approve of. Now that we have the main obstacle, something that will repeatedly prevent our character from achieving his goal, we have ourselves a movie.

3) Clever over Big – In the original script, the Greg proposal scene had him taking Pam to a baseball game and proposing to her via plane pulling a “Will You Marry Me” sign. Not only has the ball game thing been done before, but it was far too expensive to shoot. So they re-wrote the scene to happen outside of Pam’s work (she’s a kindergarten teacher). While Greg distracts Pam, her students hold letters that spell “Will You Marry Me?” behind them. Of course, all the letters are in the wrong order, so Greg must guide them into their spots with his eyes without Pam noticing. Before they can finish, Pam gets a call from her father that negates the proposal. The point here is, everybody always thinks of the big giant easy scene – even the professionals. Ignore the big. Try to do something clever instead. It always ends up better.

4) In comedies, keep having your characters fail – That’s all comedies are if you think about it. You keep setting these little goals up, then continue to have your character fail at them. Greg must make a great first impression on Jack when he and Pam arrive. He fails. Greg has to win over Jack at the big dinner scene. He fails. Greg has to win the volleyball game to prove his toughness in front of Jack. He fails. Greg has to find Jack’s cat that he lost. He fails. In comedies, just keep having goal after goal come up, and have your character fail again and again, until they finally come through in the end.

5) Design your other characters with your main character in mind – When you design your supporting characters, they shouldn’t be designed randomly, but rather as a way to affect or conflict with your protagonist. For example, Greg is a nurse. When he gets to Pam’s, Pam’s sister is celebrating her recent engagement to her longtime boyfriend, Bob. Now, what would you have Bob be? A race car driver maybe? A lawyer? A scientist? Sure, I mean any one of those could work. But the writers make him a DOCTOR, because they know it will make Greg (who’s a nurse) look even worse in the eyes of Jack.

6) Always look to go against type in comedies – Most comedy specs I read go with the obvious. So for the father our main character has to win over, they’d make him a military man with a giant dog. Not here. Jack is a botanist with a Persian cat. Go against type go against type go against type!

7) Torture your main character in a comedy whenever and wherever possible – It’s a comedy. So have fun torturing your main character. At the airport, the TSA forces Jack to check his bag, and of course they lose his bag. This leaves him without clothes, forcing him to have to wear Pam’s brother’s clothes. Now since it’s our job as writers to torture our protagonists, we can’t just give him normal clothes. Nope, the writers make Pam’s brother a younger hip-hop druggie type. Therefore Greg ends up having to wear these ridiculous oversized hip-hop clothes. We see it again later in the water volleyball game where Greg is forced to wear a tiny speedo. Torture your characters people!

8) Add twists to your comedies – Writers assume that since comedies are all about the laughs, they don’t need to add any twists or turns. The assumption is that you save those for the thrillers and the sci-fi specs. The thing is, a comedy is still a story, and every story needs a few surprises along the way to keep the audience guessing. In the original draft for “Meet The Parents,” Jack’s CIA background is revealed right away. The writers realized that doing so was kind of boring, and therefore pushed the reveal back and made it a surprise, with Jack initially pretending to be a botanist.

9) Combine scenes for Christ’s sake! – Writers always act shocked or upset or confused when I tell them they need to combine two average scenes into one super scene in order to speed up their story. Combining scenes ia great option to deleting them altogether because you get to keep all the stuff you like instead of losing it altogether. So in the original “Meet The Parents” draft, we had the big dinner scene (“I have nipples Greg. Can you milk me?”) and then a game of scrabble, where Greg accidentally pops the cork that destroys the bottle holding Jack’s mother’s ashes. The scrabble scene was extremely weak and redundant, so they just combined it into the dinner scene. Which scenes can you combine in your script?

10) When limited to one location, the easiest way to change up the plot is to bring in new characters – When you’re writing a thriller or an adventure script or, really, any script where your character is out in the world doing shit, it’s easy to spice things up. You just move to a new location with a new set of goals, stakes, and urgency. But when you’re in a single location, you obviously can’t do that. Therefore, you need to find other ways to keep the script interesting. The Greg, Pam, Jack, and Dina stuff is great. But if we’re ONLY with those four inside this house the entire script, we’re going to get bored. The easiest way to spice things up then, is to bring in new characters. They become the change. Here, it’s Debbie (Pam’s sis) and Bob (her fiancé) who pop in and start adding more pressure to the situation (with Bob being Jack’s ideal son-in-law). Immediately we feel a new energy in the script, and the story is reignited.

These are 10 tips from the movie “Meet The Parents.” To get 500 more tips from movies as varied as “Aliens,” “Pulp Fiction,” and “The Hangover,” check out my book, Scriptshadow Secrets, on Amazon!

These are 10 tips from the movie “Meet The Parents.” To get 500 more tips from movies as varied as “Aliens,” “Pulp Fiction,” and “The Hangover,” check out my book, Scriptshadow Secrets, on Amazon!