Search Results for: F word

Quick note: I’m moving today’s Amateur Friday script review to next Friday. So if you haven’t read it already, then get to it. Also, let me know which movie release you want me to review for Monday.

For those who may have forgotten, I did an interview with Jim a little over a year ago and found the attention to detail he puts into his analysis to be quite awe-inspiring. I mean this guy will dig into a scene at the molecular level to figure out what’s wrong with it. I think of myself as more of a macro guy, looking at the big picture, which is why we tend to have some fun conversations whenever we chat. I’m kinda like, “Do you really need to look at it that closely?” And he’s like, “Yeah, you do!” Having said that, my most recent obsession has been scene writing, which is more of a micro thing. Jim is actually working on a scene writing book and he told me he spends 2-3 hours on just scene writing in his new DVD set (Complete Screenwriting: From A to Z to A-List) that comes out next month. Since I want to learn more about what makes a scene great, I thought I’d bring him in and have a discussion/debate.

For those who don’t know Jim well, he worked in development for Allison Anders’ producers, produced Hard Scrambled, which includes Black List writer Eyal Podell. He works as a story analyst for A-List filmmakers and recently directed a feature film The Last Girl, which he discovered in a contest he ran. Next month he’s coming out with the most comprehensive DVD screenwriting teaching set on the market. I’ve been bothering him for a copy as soon as it’s ready and am currently getting an express shipment from New Yawk as we speak!

SS: Okay Jim, good to talk to you again.

JM: Good to talk to you Carson. I thought our last interview rocked. We were able to introduce two terms into the screenwriting lexicon. Story density and…

SS: …faux masterpiece, of course. I even give you credit for those sometimes.

JM. You’re a giver. So I see you’ve shaken things up a bit at Scriptshadow.

SS: Maybe more they’ve been shaken for me. Now let’s cut to the chase. Here’s why I brought you in today. I need to better understand scene writing.

JM: As you know, I am currently finishing up the first screenwriting book that focuses solely on scene-writing for Linden Publishing and I can tell you that two years of being immersed in just scenes has been a great learning experience for me.

SS: Oh, I know all about living inside a book. I have a million questions about scene writing but let’s start with this one. Lots of screenwriters will tell you that each scene is like a movie. They’ll have a setup, a conflict, and a resolution. Which sounds nice and pretty but when I watch movies, I definitely don’t see that all the time.

JM: At the beginning of movies, scenes are more likely to be structured like this but later, after setups are in place, scenes tend to get shorter. Think about the two lobster scenes in Annie Hall. In the later one, Alvie runs around as the completely non-neurotic woman has no reaction. The scene has a middle and an end and, on its own, gets by. However, the earlier scene where he and Annie are having fun doing the same thing is actually essential setup for that later scene to work. With the earlier scene as setup, the later scene is funnier, contains more thematic ideas about how we carry baggage from old relationships into new ones and reveals insight into Alvie’s unconscious desire.

SS: Okay, maybe I’m jumping into this too quickly. I didn’t know you were going to bring up lobsters and I’m afraid of lobsters. So let’s start with a more straightforward question – What makes a great scene?

JM: Ironically, structure. There needs to be an organic build up to a great reversal or surprise. For me, all surprise comes from setup, which means a lot of effort and craft goes into making a reversal or surprise work. Instead of using the word “goal,” which I know you like, let me borrow a phrase that actors use: “What am I fighting for?” It’s essential to have a character who is fighting for something, and then you have to find obstacles to place in front of that fight that are meaningful and fun for the audience, if not for the character.

SS: Interesting. Okay. So here’s a bigger question then – because it’s the thing that really separates the pros from the amateurs in my eyes. How do you do this for 60 scenes in a row? How do you make sure all of your scenes are good and not just have two or three good scenes scattered about?

JM: Without buying my 300-page book or ten-hour DVD set?

SS: Come on. Give us some love.

JM: There is a simple answer and a complex answer and they are the same.

SS: Is there ever a straightforward answer with you, Jim?

JM: No, and I will come back to that. The challenge is to always use the information in the scene in the most effective way. Here’s a simple example…

A girlfriend walks into a room and sees her boyfriend with incriminating, I don’t know, photos. What happens next?

SS: Well if it were me I would run.

JM: I’m talking more from the girl’s perspective.

SS: God, I feel like I’m back in school. I don’t know. There’d be an argument?

JM: Exactly. It’s a dead end. But let’s take a step back and ask what else could happen. Here’s how we can use the same information differently to create a way more dynamic scene…

She walks in and sees that he’s hiding or concealing these potentially incriminating photos. Now she has a goal, something to fight for. She wants to learn what he’s hiding or verify that they are what she worries they are. You have mystery, intrigue, blocking (as she tries to get past him to the items), secrets and conflict that can get at the nature of the relationship (blame, suspicion, mistrust, etc.). Let’s say he’s hiding invitations to her surprise birthday party instead. Depending on what the audience knows, you have either dramatic irony or a surprise twist that acts as a comeuppance to the girlfriend for being mistrustful.

SS: Okay, I’m digging that. Dare I ask what the complex answer is?

JM: Again, the challenge is to use the information in the most effective way. But now we expand the definition of information to include character orchestration, character flaws, backstories, personalities, thematic motifs, meaning built-in to locations and everything else. We’ve sort of backed into a definition of drama: Arrange any and all creative resources you have – character, story, the world – for the maximum emotional impact. If you can’t do it at the scene level, you can’t do it at the structural level.

SS: So every screenwriting book ever written has been wrong for focusing on the big picture? Including the genius Scriptshadow Secrets?

JM: That book was sooo too macro for me.

SS: Nice.

JM: I never bash other books or story paradigms. My attitude is that my detailed focus can complement everything else. How does learning forty new scene-level craft elements hurt you as a screenwriter? For instance, on the DVD set, I talk about avoiding exposition and a list of 12 ways to do it.

SS: There are exactly 12 ways to avoid exposition?

JM: No, of course not. But, remember your joke above about me not giving straightforward answers. I rarely do because I am blessed or cursed with an ability to see all things from multiple perspectives. Here’s how it manifests itself in teaching. Twelve is an arbitrary number but each one is a different take on how to avoid exposition. My hope is that viewers grasp on to one of the angles and it resonates… leading them to their own solution and understanding. But, essentially, every item on that list is a variation of the overriding principle in action: Look for a way to organize the elements for maximum emotional impact. Approaching scenes with this in mind will essentially take care of the supposed “exposition scenes”.

SS: Whoa, that’s deep. I’m gonna need an example here, compadre.

JM: Sure. This example will show how ordering “the information” can eliminate boring exposition and how scenes won’t always need a self-contained setup, conflict, and resolution.

In My Best Friend’s Wedding, Julianne (Julia Roberts) wants to break up Michael (Dermott Mulroney) and Kimmy (Cameron Diaz). Julianne’s best friend George (Rupert Everett) gives her solid advice by simply saying, “Tell Michael the truth, that you love him.”

In the next scene, Julianne talks to Michael but here is an example of a scene where the set up comes from the previous scene. We expect her to tell him the truth, and she gets close to it, a contrast that creates a nice reversal when she tells Michael the lie that she and George are engaged! However, instead of us hearing this, an ellipsis (intentional omission) and shift in point-of-view make us watch it from afar from George’s perspective as he tries to decipher Michael and Julianne’s confusing body language (mystery, suspense).

Now (surprise) Michael darts straight toward George to congratulate him. The “telling” is less interesting than the consequences. The filmmakers decided that the way to get maximum impact from this “information” would be to watch George squirm as he processes and adjusts to the lie.

We have a reversal that comes from setup: TRUTH to LIE.

SS: Okay, I like that. A reversal. We set up a scene to make it seem like we’re going in one direction, then reverse it so it goes in a different direction. Kind of keeps the audience on their toes since it didn’t happen the way they thought it would.

JM: Yeah, this sort of “change” is at the root all of my discussion about story. However, there is one more thing we have to do before the sequence is over. And it involves a burrito with a lot of carbs.

SS: Please tell me this means your DVD set comes with a gift card to Taco Bell.

JM: Come on, Carson. You know I like the finer things in life. It’s called the Chipotle Method. And it describes how sequences work.

SS: Yes! Chipotle. I love Chipotle. Are you going to buy me Chipotle?

JM: I’m going to do you one better and show you how Chipotle can be applied to screenwriting. Just like when you’re ordering from the Chipotle menu, you never go backwards. When you’re done with the rice section, you advance to the meat section. When you’re done with the meat section, you advance to the salsa section.

It’s the same with sequences. In a moment, My Best Friend’s Wedding will advance to a new sequence that will be driven by the assumption and the consequences of the lie. Once we make that crisp (y nachos) turn, we can’t go back. However, the filmmakers decided that Michael and the audience wasn’t convinced yet, so we weren’t ready for the twist.

In the cab on the way to meet everyone, he challenges Julianne and George to get clarity. This isn’t just a Q&A. Michael’s confusion has dramatic resonance and importance. He is fighting for something. He’s thinking, why didn’t I know about this? He may even be suppressing a tinge of jealousy. Once Michael accepts the reality of the lie, so does the audience and we move on to the next sequence.

The next scene is at a church where Kimmy and her family are prepping for the wedding. Julianne, George, and Michael enter. Same question: What’s the best way through this moment? Where is the heart of the drama? Who is the most agitated right now? George. Because he has to live the stupid lie. There is a nice little craft touch (surprise and joke). Julianne whispers “underplay” to George who, of course, does the opposite and acts completely-over-the-top as a way to punish her.

Michael darts out of the frame. We know that the others must learn this information to complicate the story. However, I hope everyone knows the exposition rule about never having a character explain in full something the audience already knows.

SS: Ah yes, kill me now when I see that.

JM: Exactly. So can we believe that Michael “downloaded” the facts to her? Yes. Do we have to see it? No? Another craft choice: let it happen offscreen and play it out in the reactions, which are way more fun. A SCREAM interrupts George abusing Julianne and prepares us for a surprise: Kimmy excitedly runs toward them, with her justifiably extreme perspective (Julianne is eliminated as a threat) to congratulate them.

Whew.

SS: Sheesh. Remind me to never get married when my best friend is secretly in love with me.

JM: Yeah, and we’re talking about five minutes of screen time and there are dozens of micro-craft elements that service the principle: ellipses, off-screen action, a discovery or epiphany instead of preplanning, turning exposition into conflict, exploring the not-so-obvious heart of a moment, allowing setups in previous scenes to affect the pacing of subsequent scenes and shifting the point-of-view in a scene. And I haven’t even mentioned a dozen or so dialogue elements worth looking at.

SS: So by your reasoning, there’s no such thing as an “Exposition” scene. There’s just information and the challenge to make it dramatic?

JM: Sort of. It’s almost like a self-fulfilling prophecy to admit there is such a thing as an “exposition scene.”

SS: Okay, what about another type of scene I see a lot of writers struggle with. The set-piece scene. Everyone thinks you just make all this big craziness happen and we’ll be wowed.

JM: I do think that set-pieces are important.

SS: Can you explain what they are?

JM: You’re referring to the classical definition of it being a big spectacle-oriented moment, with a wide scope, challenging logistics from a production standpoint and includes as many of the resource of the story as possible. A big dance number in a musical or the train chase at the end of Mission Impossible. And those are set-pieces. I define them a bit differently to help writers figure out the set-piece for their story.

A set-piece scene is where you go for it. Ask yourself, given your premise, concept and genre, what is the best scene I can write? For instance, in The Nutty Professor, part of the concept is that one actor plays several roles. The famous “I’ll show you healthy” dinner scene where Eddie Murphy plays all but one of the characters is an organic set-piece.

This is one of the reasons the DVD spends almost an hour on exploitation of concept. Writing a set piece is like distilling your concept into its essence or finding the perfect manifestation for it. By thoroughly understanding and assessing their concept, writers can nail their scripts’ unique set-pieces,

SS: And what about the opposite? The quieter scenes. For example, Good Will Hunting has a bunch of what I’d call ‘anti-set-piece’ scenes.

JM: Actually, that’s where I disagree 100%. In fact, almost as much as a Tarantino film, Good Will Hunting relies on set pieces. For its concept, there are several set piece scenes: the first therapy scene with Will and Sean, the Harvard bar scene, maybe even the long joke/storytelling moments and the session when Sean and Will bond over both having been beaten as kids. Without those great scenes, Good Will Hunting is an after-school special: a damaged kid goes to therapy and learns to love himself.

SS: I guess what I mean is, what about the not-so-set-piece-y scenes – where you basically just have characters talking?

JM: Earlier, I mentioned that I co-opted the phrase “what am I fighting for?” from the language of actors. The reason is because sometimes the idea of “goal” doesn’t help us tell the entire story.

SS: I love goals.

JM: I know you do but let’s take a look at the Good Will Hunting scene where Chuckie tells Will that he wants to see him get out of town. If Chuckie were his career counselor and just giving him some solid advice, the scene would suck. And a goal like “to convince him to leave” is nowhere near as strong as what I sense Chuckie’s fighting for. For his friend’s soul.

Think about it like an actor and director. If the actor said, “I am having a hard time finding the importance here. What’s the big deal about me telling him this stuff?” If you have a good answer for yourself or the character, then the scene probably works. Here, you could say this to the actor: “You and he are best friends and have been doing the exact same things together for the last ten years. But you realize now that you are keeping him back. These things that have brought you comfort and have felt good are killing your best friend, making him throw his life away. He’s not going to change anything, so you have to even if it means you will never see him again.”

SS: “What is the character fighting for in the scene?” That’s an interesting way to think about it. And speaking of these “talky scenes,” how does dialogue factor into your scene building?

JM: Typically, I’ll talk about dialogue last. Writers need to be reminded about the visuals first. I start with structure of a scene (beats and reversals) and then blocking, locations, props, motifs and strategies to help externalize the internal. Then, finally, dialogue.

On the DVD set, I discuss several advanced topics in dialogue that help writers break the rules: long scenes, talky scenes, monologues, rhetoric (storytelling within the scene itself), subconscious and extended beats. I use examples from Frost/Nixon, The Edge, Good Will Hunting, Inglorious Basterds and, of course, True Romance.

SS: I typically tell amateur writers to avoid long dialogue scenes because the longer they are, the more unfocused and wandering they tend to be. But there are writers, like Tarantino and Sorkin, who do it well. How do those guys make their endless dialogue scenes work?

JM: A lot of it is the same principles that are used in short scenes. A longer scene might need a bigger twist. It comes down to the offspring of our last interview… story density. If you have a long, talky scene, you gotta make sure there’s enough to keep it going. Is the dialogue actually action like in the opening scene of The Social Network? Are the characters casually shooting the crap or are they verbally sparring? Whether you deal with structure before or after the first draft of a scene, you can look at the finished product and determine if there is enough going on. Let’s say you think you only have half as much “stuff”. Then it’s simple. Double the amount of stuff or cut out half the fluff.

That said, there is no denying that making a long and talky scene work is easier for a great writer. Tarantino, Mamet and Tony Gilroy have all of the skills that a burgeoning professional writer has but they also have more. I discuss dozens of craft elements from the True Romance interrogation scene. Part of the reason that scene works is because Walken and Hopper are such good storytellers. Some of it comes from the writing and directing, but the actors add to the dozens of subtle touches.

Hopper will say something intriguing that raises a question and then take a long pause to puff a cigarette before he finishes the thought. He is milking the moment for suspense but it comes from character. The beat is that he is trying to lure the Walken character in to listening to the story so that he might save himself from a lot of pain and his son from death. I could talk about that scene forever.

And you got me thinking, Carson… there isnt’ room to do it here, especially with a beast like the opening of the Social Network, but I will cover the topic of long scenes and spend some time on that scene in one of my upcoming Craft & Career newsletters. It’s free and people can sign up at the site.

SS: By the way, you need to tell me which newsletter service you use later. I’m lucky if mine gets to half the people on my list. But we need to start wrapping things up. Is there anything else about scene-writing you think we should know?

You know the attention we put on the reversal twist in the sequence from My Best Friend’s Wedding? Dirty little secret, that skill… to turn a dramatic situation sharply so the audience and characters (when applicable), FEEL 100% that there is a new and opposite situation, is the underlying craft to all of screenwriting. Most books look at it only at a story structure level – acts and sequences – but my book and DVD take a micro approach and look at it at the level of scenes (beats), dialogue and even action description. If you can absorb and embrace the craft in making a line of dialogue or piece of action description turn, you will see the growth ripple through all of your screenwriting.

SS: Whoa. That’s a pretty powerful statement. Okay, I just want to know a little more about your DVD set before we go. What sets this apart from all of the other screenwriting teaching materials out there?

Remember, I directed the first 40 DVDS in the old Screenwriting Expo Series. I know what’s out there. I cover topics in theme, exploitation of concept and scene writing that no one else is doing.

And, from a production values standpoint, we weren’t trying to do anything but a talking-heads presentation on those Expo DVDs. My new set contains more than an hour of motion graphics. They add a ton of clarity to the viewing experience. There are some cool animated script excerpts that accompany scene analysis as well. And there are graphs and images that illustrate difficult concepts like character orchestration in ways that have never been done before.

And the great thing is that if your readers want to order it on my site, they can get 40 dollars off! Just use the code “SHADOW” when you order. It’ll be good through the end of the month.

SS: It sounds like you’re pretty passionate about it.

JM: This has been a two-year project and, yes, the DVD set is measurably exhaustive: I have poured everything I know about screenwriting into it. But on a personal note, I am risk-taker at heart. I always look to Go Big or Go Home. I feel that this is my legacy as a teacher. I am really proud of it and I believe it will positively impact and inspire writers of all skill levels.

SS: All right, Jim. Thanks as always for stopping by.

JM: Carson, I live for stopping by Scriptshadow.

SS: That is such a lie but I don’t care because it makes me feel all gooey inside.

JM: I know. The gooeyiness was set up in the first act.

SS: Take care and good luck with the DVD set!

JM: Thanks. This was fun.

To learn more about Jim Mercurio, you can head to his site. If you want to take advantage of the DVD set discount, head over to this page and use the code “SHADOW” when you purchase. If you have any questions, you can send Jim an email. Also if you enjoyed this scene writing discussion, check out a sample of his $19.99 online scene writing class which includes excerpts from the first two lessons and an outtake from our interview.

A re-posted old review of the screenplay that recently played at 2013 Sundance with Natalie Portman and Shia LeBoeuf in the leads.

Genre: Comedy/Crime

Premise: After his mother dies of cancer, Charlie takes a trip to Budapest. On the flight, he meets a man and promises to deliver a gift to his daughter, who, when he meets her, he promptly falls in love with.

About: Matt Drake has been writing a long time for someone who’s just now breaking through. He wrote the 2000 independent film, “Tully,” as well as an episode of “Spin City” in 2002. But for the next five years, Drake disappeared off the radar. Then, in 2007, all that persistence paid off when he landed on the Black List with this script, which received 14 votes (Top 15). Another 3 years went by where Drake presumably did a lot of assignment work, then a week ago made noise by writing Todd Phillips’ mysterious new super-comedy known only as “Project X.” I’m reviewing today’s script in hopes of getting someone to send me that script. So if you’ve got it, dammit, send it!

Writer: Matt Drake

Details: 119 pages – June 2007 draft (This is an early draft of the script. The situations, characters, and plot may change significantly by the time of the film’s release. This is not a definitive statement about the project, but rather an analysis of this unique draft as it pertains to the craft of screenwriting).

It isn’t often you open up a script and meet your main character dangling upside down off a bridge in Eastern Europe to the sounds of a Zsa Zsa Gabor voice over, who’s pontificating about love, specifically the woman this man has fallen in love with, who’s standing in between two gangsters, pointing a gun at our hero’s heart, which she then proceeds to pull the trigger on in order to kill said hero. Then again, there’s nothing quite like reading “The Necessary Death Of Charlie Countryman,” a script as unique and unpredictable as a 3 a.m. visit to Jack In The Box. Whether you’re into this kind of thing or not, “Necessary Death” is a script you’ll be compelled to finish, and that’s, at the very least, a big achievement in this distraction-plagued world.

Charlie Countryman is a confused young man to begin with. But when he and his stepfather are forced to pull the plug on his brain dead mother, his grip on reality slips into the ether. And if that soap opera hasn’t fried enough circuits, Charlie’s better half hightails it out of Relationshipville, citing Not-interested-itus (I hate when girls come down with this btw). And so, lost, the last traces of normalcy and home sucked away by that cruel darling called Life, Charlie makes the perfectly valid decision to fly off to Bucharest, a country he knows nothing about, in hopes that the foreign-ness of it all will make his memories disappear.

However, on the plane to Budapest (the first leg of the trip to Bucharest), Charlie meets a jolly old man whose combination of broken English and unbridled enthusiasm make him adorable on eight levels. The man just spent a week in Chicago courtesy of his daughter – a gift which allowed him to fulfill a lifelong dream, to see the Cubs play at Wrigley field. Despite Charlie’s attempts to ignore him, the man continues to tell Charlie about his beautiful daughter, and shows him the gift he’s purchased in return, one of those silly batting helmets with beer cup holders attached. Finally the man shuts up, clearly petered out by his nonstop chattering, and falls asleep on Charlie’s shoulder. And doesn’t wake up. Ever. Yes, the old man dies napping on Charlie. When Charlie informs a stewardess about this little snafu, he’s told they’re in the middle of the Atlantic and there’s not much they can do. And since the flight is full, Charlie will have to remain this dead man’s pillow for the next five hours.

As if the trip weren’t weird already, just before they land, the old man turns to Charlie and asks him if he can deliver that wacky beer hat to his daughter. Oh, I didn’t mention? Charlie can occasionally speak to the dead.

Now in Budapest (he didn’t make it to Bucharest), Charlie goes searching for this young lady. And when he meets her, well, she’s so gorgeous he can barely form words into coherent sentences. The two are drawn together by their recent tragedies, and somewhere within the first ten minutes of the conversation, Charlie falls in love.

Unfortunately, Gabi turns out to be a little more than Charlie bargained for. When she was 17, she fell in love with a man named Nigel who operated a business which, although unspecified, seems to involve killing people. The relationship didn’t last, but Nigel never technically accepted the resignation papers. Besides all the killing he engages in, he also makes it a priority to ensure that no men get to enjoy the company of his quasi-wife. So obviously, when Nigel sees Charlie following her all over the city with his tongue lapping up street debris, he pops in to warn Charlie to go find some other avenue of entertainment. But what Nigel doesn’t realize is that it’s already too late. Charlie is in love, and he’ll go to the ends of the world – or, in this case, Budapest – to be with her. And that includes enduring the ongoing Zsa Zsa Gabor voice over chronicling his misfit adventures. But wait, how the hell did this love affair end up in Gabi killing Charlie? That is the reason, my friends, to read the screenplay for yourselves.

“Necessary Death” was tailor made for the Black List. It’s odd. It has a strong voice. You’re never sure what’s around the corner. And it’s well-written. But at a certain point the script struggles to decide if it wants to embrace its oddness, or salvage some kind of traditional storyline. I love scripts that are different. I love scripts that are weird. But I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again. The weirder your script is, the harder it is to finish. Because the whole point of structure, is that it sets the story up for a proper climax. Without said structure, it’s all just a lot of crazy wacky sequences. This almost always results in the writer trying to be even crazier and wackier in the final 30 pages, and the third act subsequently comes off as desperate as a result. “Necessary Death’s” saving grace is that it eventually commits to the love story, which gives the screenplay a purpose, but it still feels like it has one foot squarely in each of the two worlds (traditional and crazy) and that lack of commitment had a neutering effect.

I really went back and forth on this, trying to decide how much this bothered me. Then I remembered – I’m a story guy, first and foremost. I like a good well-crafted tale. And only having that single thread – Why does Gabi kill Charlie – to look forward to, wasn’t enough meat for me. I wanted the two tacos, the chili fries, IN ADDITION to the Jumbo Jack, you know? But for those writers out there who want to see how to stand out, how someone emerges with a unique voice, they may want to check “Necessary Death” out. It’s definitely interesting. It just wasn’t for me.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: One of the more heavily debated mechanical details in the screenwriting world is the use of the word “We” in your description paragraphs. Such as “We turn around to see…” or “We slide forward where it’s revealed…” There are writers out there whose heads will explode at the mere mention of another writer using this style. Some will want to murder you. They will argue with you in screenwriting messageboards until you hit triple-digit thread replies. Trust me, I’ve seen it happen. And the thing is, I don’t have the slightest idea what the big stink is. I suppose it’s because it puts the reader in the position of the camera (“we” implies the “camera”) and that’s technically a no-no. But I’m here to tell you, I see this style in professional screenplays ALL THE TIME, including in this one. So rest assured, if you like to do it, keep doing it, and ignore anyone who tells you your script has no chance of selling if it’s included.

Believe it or not, I didn’t like this movie for a long time. I’m not really into the whole stoner culture and this film was basically a promotional tool for the Toke and Tug crowd. But I watched it again recently (sans the close-mindedness) and I was kind of blown away. The character work here is amazing (not that I should be surprised. It’s written by the Coens) and the dialogue is top-notch. And that’s the main reason I wanted to give it the Tuesday treatment. I wanted to see if I could snag a few dialogue tips. You know, the more I study dialogue, the more I realize it’s less about the actual writing of the dialogue, and more about all the things you do before the dialogue. In other words, the characters, the relationships, the situation. If you get all those things right, the dialogue writes itself. That observation is on full display here.

1) Introduce your hero in a way that tells us EXACTLY who he is – I know I put this tip in my book, but I couldn’t dissect this script without bringing up how perfectly it’s executed here. We meet “The Dude” (Jeff Bridges) at the grocery store, shopping in the middle of the night, wearing a bathrobe. I mean, how do you NOT know who this character is after this scene? And yet I continue to see writers introducing their characters in unimaginative situations that tell us little to nothing about them. Come on guys! This is a fairly simple tip to execute!

2) CONFLICT ALERT – You’ll notice that in pretty much the entire script for The Big Lebowski (almost every scene) people are in disagreement. Walter and The Dude have two completely different philosophies on life. Walter thinks Donny (Steve Buschemi) is a total moron and is always yelling at him. Walter pulls guns on bowlers who cheat. The Dude and Mr. Lebowski never agree. The Dude and the Nihilists don’t agree. The Dude and the thugs don’t agree. Since there’s zero agreement in every scene, there’s always conflict. And guess what conflict leads to? That’s right, good dialogue.

3) Use passionate characters to distract us from exposition-heavy locations/scenes – The bowling alley where our characters always meet up has NOTHING to do with the story. It’s merely there for expositional purposes. Technically, our characters could be discussing this stuff anywhere (a coffee shop, a workplace, a restaurant). Here’s why the Coens are clever though. They know if the location is random, the exposition will stick out like a sore thumb. So they create this bowling alley setting and have one of their characters be the most DIE HARD BOWLER EVER (Walter). This is no longer a random setting. It’s an institution. Discussions here matter because this place matters to our trio (particularly Walter). I see too many scripts where writers lazily place their characters at coffee shops to dish out exposition. These scenes ALWAYS smell like exposition. This tip is a great way to avoid this issue.

4) Give someone in a position of power a handicap – The irony behind this make-up always works. The extremely rich Mr. Lebowski is in a wheelchair.

5) (DIALOGUE) Conversation Diversion – An easy way to write some good dialogue is to create a diversion for one of the characters in the conversation, so that he’s dealing with someone else at the same time he’s dealing with the primary character. So in “Lebowski,” we’re at the bowling alley and the The Dude is asking Walter what the fuck they’re going to do about losing the money. At the same time, Donny informs Walter that the semifinals of the tournament are on the Sabbath. Walter freaks out because he’s not allowed to bowl on that day. So he’s yelling at Donny to change the day at the same time that he’s explaining to The Dude that they have nothing to worry about. A conversation diversion is a great way to spice up dialogue.

6) Always try and escalate the stakes around the midpoint – Readers get bored quickly. The key to preventing their boredom is to keep them on edge. A great way to do this is to make the second half of your story BIGGER than the first half. You do this by raising the stakes in the middle of the script. Here the stakes are raised when Mr. Lebowski tells The Dude that because The Dude took his money, he told the kidnappers to do whatever they wanted to to get it back from him. He then shows Dude a severed toe the kidnappers sent. This isn’t a game anymore. The stakes have been raised.

7) Give your character a plan then find a way to fuck it up. – Really, you should approach every story you tell this way. Give a character a plan (he has to achieve something) then fuck it up for him. The result is entertainment. This tool should not only be used for the macro, but for individual sequences as well. For example, The Dude plans to do a money drop with the guys who kidnapped Mr. Lebowski’s wife, Bonnie. Before you write that sequence, ask yourself, “How can I fuck this up?” Well, Walter asks The Dude if he can come along. He does, and halfway there, Walter says he’s got his own plan. He’s going to give them a fake suitcase of his dirty underwear and keep the ransom money for themselves. Adding Walter fucked things up.

8) (DIALOGUE) The One-Sided Conversation – This is another dialogue scene that always works. Create a “conversation” where only one person is talking the entire time. The audience is so used to a back and forth, that the lack of one is somewhat jarring and ignites the scene. Here we have the famous scene where Walter and The Dude go to the house of the guy they THINK stole their money. It turns out to be a 16 year old kid. Walter proceeds to grill the kid for the entire scene. The kid just looks back at him the whole time and does nothing (this is followed by the classic moment where Walter destroys his car).

9) Keep throwing shit at your protag – Just keep throwing terrible things at your protag. That’s all this movie is. Someone steals The Dude’s rug. Walter botches the drop, putting The Dude in danger. The Nihilists come after him. Mr. Lebowski comes after him. His car is taken. The suitcase is stolen. Hurl the worst things imaginable at your protag and watch him react. It’s always interesting.

10) Do everything in your power to avoid writing two slow scenes in a row. ALWAYS KEEP THE STORY MOVING – The cool thing about this movie is that after every “slow” scene (which are usually the bowling scenes), something YANKS The Dude back into the story. In other words, there’s never two slow scenes in a row. All of these things happen after a slow scene: Mr. Lebowski wants to meet. Jackie Treehorn (the porn king) wants to meet. The Nihilists show up when he’s taking a bath. Maude Lebowski (Julianne Moore) needs him to come over right away. They walk out of the bowling alley and their car is on fire. Lots of young writers think they need three or four scenes of detox before throwing the reader back into the story. This script proves that you only need one.

Bonus tip – For good dialogue, create an opposite dynamic between your two main characters – Whichever two characters talk to each other the most in your script, create the most exaggerated dynamic between them possible. Because at their very core, they will be the opposite, their conversations will be filled with conflict. And conflict = good dialogue. Walter is a war vet. The Dude is a Pacifist. I mean, how can these two NOT have great dialogue together?

These are 10 tips from the movie “The Big Lebowski.” To get 500 more tips from movies as varied as “Star Wars,” “When Harry Met Sally,” and “The Hangover,” check out my book, Scriptshadow Secrets, on Amazon!

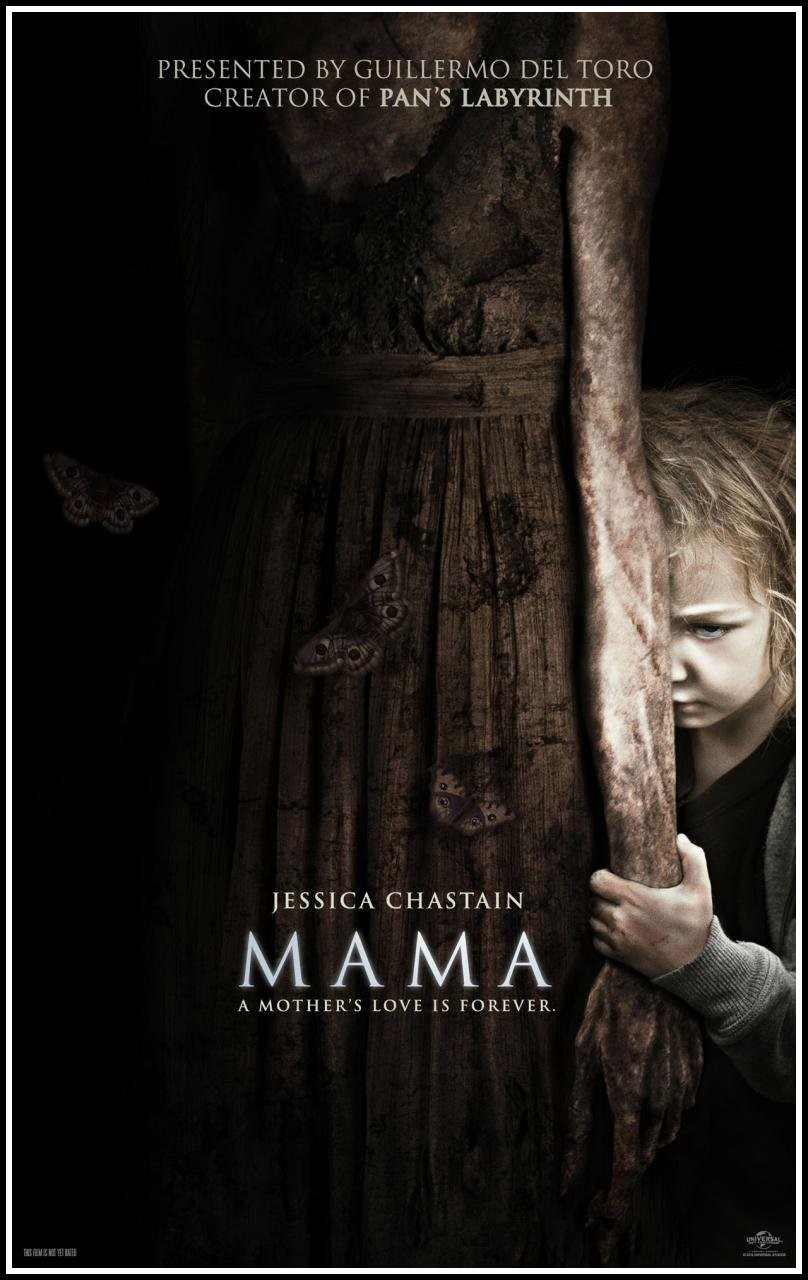

I’m not sure what I was expecting from a January horror film. But it certainly wasn’t what I got. Everybody say it with me: “MA-MA.”

Genre: Horror

Premise: (from IMDB) Annabel and Lucas are faced with the challenge of raising his young nieces that were left alone in the forest for 5 years…. but how alone were they?

About: “Mama” seems to be the result of a growing trend of directors showing their chops via short films, then expanding those short films into full features or feature assignments. Mama started out as a 2008 short and has now been brought to the big screen, at least in part by Guillermo del Toro (it’s unclear how involved he was with the production). Co-writer Neil Cross is the creator of the show “Luther,” with everyone’s famous Prometheus captain in the lead role, Idris Elba. Andres Muschietti is the co-writer with his wife, and also the director of the film, which stars Jessica Chastain, the Academy Award nominee from Zero Dark Thirty.

Writers: Neil Cross and Andres Muschietti & Barbara Muschietti

Warning.

This movie is scary.

This movie is really scary.

But this movie will also make you cry.

It will hit you on an emotional level that you were not prepared for.

You will be in the theater doing your best to suck back tears before those dreaded lights come on in the end and everybody can see how much of a wuss you are.

In other words, it’s the ideal screenplay that I always ask for in the horror genre but never get. I get cheap scares. I get cheap thrills. I get cheap characters. I never get horror that makes me feel something. And I sure didn’t expect it from this film. I remember seeing the preview in the theater a month ago and laughing. You had kids crawling around like spiders while the word “Mama” was echoed theatrically in a child’s voice. I didn’t see any way this could be anything other than awful.

Boy was I wrong. Mama is the best movie I’ve seen in half a year. It would’ve been in my Top 5 of 2012 easily. Instead, it was released in the studio dumping ground of late January and February. But this is far from a piece of studio trash.

Mama starts with a harrowing opening scene featuring a deranged suburban father breaking down after the 2008 financial meltdown. He kills his wife, a couple of his co-workers, then grabs his two young daughters and starts driving. Where? He doesn’t know. He just needs to get away from here. His disorientation eventually results in his car shooting off a ledge in the mountains. The family survives the fall and starts marching through the woods, looking for shelter.

They find it in a small dilapidated cabin. But soon after going inside, they realize that somebody else lives here. And when Daddy decides to take the rest of the family with him to that big suburban block party in the sky, that house host (who we only see parts of) rips his head off and starts raising the girls herself.

Five years later, the father’s brother, who thankfully still has his head on straight, is desperately looking for the family. Miraculously, after looking everywhere in those mountains, he finds them. Except the girls are anything but the ones who left on that fateful day. They’re alone, malnourished, dirty, and, well, “feral” would be the only way to describe it. They scamper about on all fours and haven’t seen a bottle of Head & Shoulders in quite some time, as you can confirm below.

Over the next three months, a psychiatrist and his team carefully work the kids back into society and eventually the daughters are able to move in with their Uncle and his girlfriend, the too-cool-for-school Annabel. Annabel has her own shit going on. She’s a guitarist in a rock band. She’s used to living life on her terms. She was just dating this guy cause he was fun. Now she finds herself in the unenviable position of playing mother, a role she’s clearly not ready for.

After the girls move in, strange things start happening. The couple begins to hear noises, and the girls can be heard playing and laughing with somebody. One night, the disturbance becomes so intense, the Uncle gets up to see what he can find. He sees something that can’t be explained, stumbles backwards, over the railing, and slams headfirst into the stairs below, the force so great it sends him into a coma.

You know what that means . Annabel is now stuck on her own with the kids. And I don’t care if you’re mother of the year. No one wants to get stuck with kids who scamper around on all fours and tell you things like, “Don’t hug me. She’ll get jealous.” At least no one I know. While Annabel’s simply trying to make it through each day, the children’s psychiatrist has been studying the children’s tapes, and becomes interested in the girls’ repeated references to a woman who raised them in the cabin. At first he assumes that woman is part of their imagination. But the more he looks into it, the more it looks like this woman may in fact be real. And that she’ll stop at nothing to get her kids back.

Ma-ma.

The structure behind this screenplay was exceptional . I can’t remember reading a horror script that had this much forward momentum – that never got boring – that never got weak. There were a lot of things that contributed to that. Let’s see if we can identify some of them.

As you all know, I like screenplays with strong character goals. And that doesn’t change when it comes to the horror genre. I love Naomi Watts desperately trying to solve the “7-Days” tape in The Ring. I love the family trying to get their daughter back in Poltergeist. I love the mother trying to exorcise the demon inside her daughter in The Exorcist. But with the horror genre, you occasionally get the type of movie where a force is haunting our characters and we just sort of sit back and watch it happen. You see this, for the most part, in movies like, “The Others” and “Rosemary’s Baby,” and more recently in the Paranormal Activity franchise.

These are much harder stories to pull off because nobody’s going after anything. By including a character goal, your story gets pulled along the track by someone seeking to solve a problem. When you don’t have anyone pulling, your’e obviously stuck in one place. And how interesting is that?

So what Mama does is really cool. It does both. Within the house, Annabel is taking care of these girls while all this crazy shit is happening. That’s the “haunting” section. Then the psychiatrist has a goal. He suspects that the “mother” these girls are referring to wasn’t made up, as he originally suspected, but that she might be real. So he starts investigating that possibility. This works really well since we’re able to cut back and forth between the haunting and the investigation, allowing a sort of “cheat” where we get the best of both worlds.

Another real strength of Mama is its main character, Annabel, and the situation it places here in. We establish early on that she’s a terrible parent and is only in this thing for the Uncle. So when the twist comes with the uncle falling into the coma, the story switches gears to place the worst character for the job in a position where she has to do the job. What a great story choice! I mean how much more compelling is that than having the loving doting perfect Uncle around all the time? If that were the case, there would be no conflict, because Annabel would never be forced to deal with the children. This was one of several really slick story choices I give the writers credit for. Get the fucking uncle out of the picture.

Then there was the brilliant integration of the subplots. You had the psychiatrist. You had the Uncle in the hospital. You had the grandmother, who wanted custody of the kids. Then, of course, you have the girls’ own interactions with Mama herself.

And the reason I’m going gaga over all of this is because I read the bad versions of these screenplays every day. Where there are no subplots. It’s just people in a house with something weird attacking them. And that gets boring after 30 pages. Here we have so many subplots to keep weaving in and out of the main plot, that the story always remains fresh.

I also loved the decision to use two children. 99 out of 100 writers would’ve made the more predictable choice of going with one child, because one spooky child is what we always see. Of course, one spooky child is also cliché and therefore boring. By adding a second child, it opened up all these new avenues, and boy did the writers take advantage of it. One of the most brilliant choices in was to have one of the children pull away from Mama (and gravitate towards Annabel) and the other prefer Mama.

(spoiler) This created the all important CONFLICT that you want in every character dynamic (even if the dynamic is two young children) and led to a shocking, emotionally satisfying climax, one that you never could’ve achieved with a single child. And it’s why I keep going on about this same old advice – AVOID THE OBVIOUS CHOICE. Not only is it boring, but when you push yourself to go with the non-obvious, it almost always opens up new story directions that you never could’ve predicted. Why? Because nobody else has gone down that path before! so they’ve never found those choices.

There were only a few minor things that bothered me. I didn’t understand how this thing could travel from house to house through the walls. That was vague. The moths seemed more spooky than story-relevant (although I did like their payoff). And there was a laughably clumsy moment late in the story where Annabel is driving to the forest and nearly runs over the Uncle, who just happened to be stumbling onto the road at that moment. But other than that, this was a GREAT cinematic experience, the kind you dream of having every time you pay 18 bucks. Top-notch storytelling, top-notch movie-making. I will go to see this one again!

[ ] What the hell did I just watch?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the price of admission

[x] impressive (go see it now!)

[ ] genius

What I learned: I absolutely LOVED the execution of the character flaw here and it fits in perfectly with the article I wrote the other day. Annabel’s flaw is that she doesn’t want to parent. She doesn’t want that responsibility. You’ll notice that the entire story, then, is designed to challenge this flaw. Annabel is thrust into the position as the sole parent of two young girls. They’re resisting. She’s resisting. But as the script goes on, she starts to change, begins to care for them, and in the end, (spoiler) she’s willing to fight an otherworldly creature with her life in order to save them. It’s the ultimate character transformation, and it’s a big reason why this ending was so emotional.

Warrior may not have made the splash it had hoped to, but that doesn’t mean MMA-themed movies are dead. Someone out there is going to write an MMA-centered classic. The question is, is it today’s writer?

Amateur Friday Submission Process: To submit your script for an Amateur Review, send in a PDF of your script, a PDF of the first ten pages of your script, your title, genre, logline, and finally, why I should read your script. Use my submission address please: Carsonreeves3@gmail.com. Your script and “first ten” will be posted. If you’re nervous about the effect of a bad review, feel free to use an alias name and/or title. It’s a good idea to resubmit every couple of weeks so your submission stays near the top.

Genre: (from writer) Action

Premise: (from writer) Way To The Cage chronicles the fictional formation of ultimate fighting when an underdog brawler fights his way off the streets and forces his way onto the world stage to challenge the international no holds barred champion in the first Mixed Martial Arts match ever sanctioned in the United States.

About: Says the writer, “ I’ve been on the mat with some of the best fighters in the world and choked unconscious. But I’m just a writer. What if I had set out on a journey to discover myself, and along the way…created the perfect fighting style?” Also: “Way To The Cage placed in the 2nd Round of the Austin Film Festival Competition 2012 (Top 10% out of 6,500). You should read it because of my personal experience watching Mixed Martial Arts blossom in the early years. I also wanted to treat reoccurring themes in “fighting” movies with more respect. And didn’t want to fall victim to using sex & violence as cliches.”

Writer: Richard Michael Lucas

Details: 114 pages

This is sort of an offbeat choice for a script review. I’m not really into the MMA. I’m a lover, not someone who jumps into a cage and fights to the death. But I also recognize that if you only stay within the genres that you like as a reader, reading can get boring. You miss out on some potentially cool experiences. “Desperate Hours” is not a script I would’ve normally picked up. Ditto “The Ends Of The Earth.” And both of them turned out to be great.

Also, I like to occasionally review a script that’s placed in a well-known contest. It’s important for a writer to not only know the level of quality required for a script sale, but the level of quality required to be a Nicholl finalist, or a Nicholl quarter-finalist, or, in this case, a top 10% finisher in the Austin Screenplay Competition. So what *is* the difference? Probably consistency. You often find SOME good things in these scripts, but there are just as many things that need work. I’m hoping that that’s not the case here, though. I’d love it if the competition got it wrong and we found a gem.

Way To The Cage places us back in 1992 and introduces us to 19 year-old Philly local, Josh King. Josh is an odd duck, someone who’s not interested in pursuing the well-traveled blue collar path of his fellow Philadelphians. He wants to fight for a living. Which is hard enough as it is. I don’t know how many people make a living at fighting, but it’s probably less than the number of people who make a living at screenwriting, so it’s a tough gig.

But Josh has managed to make things even tougher on himself. He doesn’t want to box or wrestle. He wants to be a part of a new Japanese/Brazilian movement of free-form fighting known as Mixed Martial Arts. In other words, Josh has made his goal about as impossible as it can be.

After studying the fighting styles of these unique fighters through a series of underground bootlegged tapes, Josh perfects his own unique approach to mixed martial arts before heading off to Los Angeles where this free-form fighting style is in its infancy. It’s there where he becomes obsessed with finding and fighting the current face of MMA, Brazilian mega-fighter, Merco.

Josh fights his way up through a series of former Merco opponents and gains enough respect to get invited to Japan to fight on the MMA circuit there. At first he gets pummeled. But Josh’s strength is his ability to invent his own moves and figure out his own solutions. So soon he’s defeating the very fighters he was losing to, and finally gets the big showdown he’s been waiting for – a one-on-one with Merco.

I can see why Way To The Cage made it to the second round at Austin. It looks like a screenplay. It smells like a screenplay. The writing is clean. There’s none of that stopping and needing to re-read sentences that plagues so many amateur scripts. From a bird’s eye view, Way To The Cage looks like a professional piece of work. Richard deserves credit for that.

However, when you take a closer look, when you start to dissect the scenes and the characters, you find that, unfortunately, there are some issues here. And I’m hoping Richard will indulge me. This isn’t meant to disparage what he’s accomplished. It takes a lot of work to get to this point in your writing. But in order to take the next step, just like all the work Richard had to put in to get to the top of the fighting game, he’ll have to put in to become a top writer.

The biggest problem is that there isn’t any drama. Remember, drama emerges from resistance, from conflict. Forces and obstacles colliding against each other. Like we were talking about the other day with The Graduate. Mrs. Robinson desperately wants to seduce Ben. Ben desperately wants to escape Mrs. Robinson. Each character is the other’s obstacle, and the resulting collisions are what make the scene so electric.

There’s very little drama or conflict in Way To The Cage at all. In fact, in the first 30 pages – the entire first act – there isn’t a single scene that I’d say has conflict (except for maybe the Bronco fight). Usually it was Josh easily defeating some street fighter. Josh talking with his father. Josh talking with his best friend. Josh talking with his ex-girlfriend. Josh sitting outside his mother’s grave at the cemetery.

Compare that to Rocky. In the first act we get a great scene where Rocky finds out his gym locker’s been revoked. He barges into the gym and challenges Mick, the owner, about it. Mick fights back with a vengeance and the two go at it in front of everyone. THAT is conflict. THAT is drama. THAT’s a scene we remember.

We don’t get anything like that here. It just feels like Josh is drifting through his days. That’s not to say setting up Josh’s everyday life isn’t important. But you have to do it in a way that ENTERTAINS US. And the key to doing that is giving your characters goals (find out why my locker’s been taken from me) and putting obstacles in front of those goals (Mick refuses to give him his locker back).

Secondly, there were way too many obvious and cliché choices in the story. I say this all the time but when I’m 30 pages ahead of the script, when I’m never surprised, when every choice is something I’ve seen in a previous movie before, I have no choice but to check out. And the writer shouldn’t be surprised about that. He would do the same thing if he were me reading a script like this. Which brings up an interesting conundrum. Too many writers believe that when THEY’RE writing the cliché, it’s somehow different, because THEY’RE different, and therefore the cliché will come off differently.

I mean here we have the dad who wants his son to give up on the fighting thing and come work with him on the docks (make the “safe” choice in life). We have a dead mother. We have scenes where dad and son are remembering how great mom was while sitting at her grave. The romantic interest “doesn’t date fighters.” I just wasn’t getting anything that I hadn’t seen in these kinds of movies before.

The one area where I saw some potential was with Tommy, Josh’s friend. Although it’s unclear exactly what happened, it appears that six months prior, Josh crashed a car with Tommy in it, destroying his legs and putting him in a wheelchair. That storyline could’ve gone to some interesting places. Strangely, however, Tommy seemed to have no problem with Josh whatsoever. And when Josh moves to LA, Tommy’s storyline is pretty much done. Again, there was zero conflict in their relationship, zero issues that needed to be resolved.

The thing that was so great about Rocky was that it hinged on three really fascinating relationships. There was Rocky and Adrian. Rocky and Paulie. And Rocky and Mick. None of those relationships were easy. That’s why we remember Rocky. We don’t remember Rocky because of the fighting. And unfortunately, that’s all Way To The Cage seems interested in. There are tons of fights and they’re all meticulously detailed. Which is great. It’s fine. But as a reader, I’m not interested in how well a writer can execute the description of a reverse choke-hold. I’m interested in who the character in that choke-hold is. What are his demons? What are his flaws? What’s holding him back? What needs to be resolved with the other people in his life?

I mean what needs to be resolved with any of these characters here? Nothing really. Him and his dad are fine. Him and his friend are fine. Even him and his ex-girlfriend get along well. The only people he doesn’t get along with are a few of the people he fights. And since we barely know those people, we don’t really care if Josh defeats them or not.

To Richard’s credit, he does a really good job building up Merco, the villain, so that when he finally enters the picture, we’re intrigued to see how it will play out between him and Josh. But even there, there were some strange choices that lessened the impact of their collision. There was something about others wanting Josh to become an artificial “villain” to Merco so promoters could create a rivalry. It was really murky and didn’t make a whole lot of sense.

Moving forward, the number one thing I’d recommend Richard do is study conflict. You have to learn how to create conflict in every scene so that you can have drama in those scenes. If all your characters are doing is talking through stuff, that’s not a scene. And three or four of those in a row and your script is dead. When I see that, I know the script’s not going to be any good. Injecting drama is a MUST so you HAVE to learn how to do it.

I’d also probably re-work the structure. Nothing really happens in Philly for 30 pages. The LA section also wanders a lot. It isn’t until we get to Japan that it feels like our character is beginning his story. That’s where he encounters the most conflict, the highest stakes, his first true setbacks. It’s where we get some actual CONFLICT. Yet it’s the shortest part of the script.

I’d start the story a few years later as well, when this kind of fighting had already taken off. And Josh (whose unique style has made him a local celebrity in Philly) realizes that if he’s going to make a living off MMA, he’s going to have to go where the big boys are, in LA. Then get rid of Japan. It’s too weird to cram a whole other country into the final act. Establish some big tournament in LA as soon as Josh lands (the first ever MMA tournament), and Josh struggles as soon as he gets there. Unlike Philly, there are fighters coming in from all over the world. It’s a different league. But in the end, preferably through overcoming his flaw (more on that in “What I learned”) he wins the tournament and establishes himself as the best.

I realize that’s a bit cliché but the big problem with this script is that it wanders. It NEEDS FOCUS. An announced tournament early on does that. That’s why the underrated Warrior worked. That’s why Rocky worked. It’s why The Karate Kid worked. I mean you can take a chance and focus on a more understated “street” like finale. But Sylvester Stallone found out what happens when you do that when he made Rocky 5. It didn’t work out.

Anyway, I’ve been pretty harsh here. But I’m sure Richard has endured much worse on the mat. Improvement is the name of the game in screenwriting. Learn from your mistakes, figure out how to get better, then use what you’ve learned in the next script. Good luck! :)

Script link: Way To The Cage

[ ] Wait for the rewrite

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: “Way To The Cage” is a good example of what happens if you don’t give your main character a flaw. Like we discussed yesterday, no flaw typically means no depth, and I definitely felt that here. Josh was a pretty straightforward uncomplicated character (he just wanted to be a fighter) so he was kind of boring. Looking back at the flaws I highlighted yesterday, we could have added any number of those to Josh to give him some meat. Maybe fighting was more important to him than friends and family (Flaw #1). Maybe he’s too reckless, using his fighting for the wrong reasons, which keeps getting him in trouble (Flaw #8). Or maybe he can’t move on from his mother’s death (#11). A solid character flaw here would’ve added a lot to the hero and a lot to the story.