Search Results for: F word

As a kid who grew up on Star Wars, and who loves the original Star Wars more than anything, you would think that A New Hope would be the most memorable movie from my childhood. But that actually isn’t true. Both Empire Strikes Back and Return of the Jedi were more memorable.

The reason for this is, Star Wars began a new expectation in Hollywood that, with each new blockbuster film, you were going to see things you had never seen before. And when I went to those sequels, that’s exactly what happened. I saw AT-AT walkers and tauntauns. I saw aliens with lobster heads and speeder bikes shooting through gigantic trees.

Back then, Star Wars was the defining franchise for Hollywood’s new mantra: GIVE THEM SOMETHING NEW AND FRESH. Every movie that had aspirations of being a hit had to give audiences something genuinely new. It’s why Jurassic Park did so well. It’s why Men in Black and Independence Day and The Matrix and Aliens did so well. Hollywood operated off of this idea that why would someone see a movie if all you were going to give them was something they’d already seen?

But somewhere around 2005, when comic book movies started to take over and special effects companies were able to create anything you could imagine, it all of a sudden became a lot more difficult to give audiences something new. Once you have a man in an iron suit fighting a giant green monster in the sky or five-story tall robots hurling each other into city buildings… what can you really show audiences at that point that they haven’t seen?

Marvel realized that this was going to be a problem. Whether intentional or not, they had opened up Pandora’s Box. How do we tempt audiences to come to theaters when we’ve already given them everything? They’ve come up with a temporary solution. More superheroes. You cram more spidermen, more Avengers, and more surprise guest caped crusaders into your flick, because, technically, you are still giving audiences something new. You’re giving them more superheroes to play around with.

And Marvel has a quasi stay of execution since they now own 20th Century Fox. People are going to be excited to see the X-Men hanging out with Thor. They’re going to be excited to see the Silver Surfer cutting a jib with Starlord. They’re going to love when the Fantastic Four goes on an adventure with Spidey. But eventually, even that will peter out. At a certain point, people are going to say, “What’s new? What’s next?”

I think about this a lot because you – as in you, reading this article right now – are the solution to this problem. It will be up to you to come up with the next big thing. The question is, is it possible to come up with the next big thing anymore? Is it possible to shock readers anymore? Is it possible to show them something they’ve never seen before?

As someone who reads pretty much everything, I can’t remember the last time I read something totally fresh. I’m not even talking about the whole script. I’m talking about one set piece I haven’t seen before.

There are scripts that are KIND OF unique. Colin Bannon, who wrote yesterday’s script, for example – he wrote a script about ultra marathon runners who participate in a death race where an evil mythological creature kills the runners one by one. Have I ever come across that specific concept before? No. But I’ve read plenty of scripts where people get killed by a creature in the woods.

Which leads us back to the question, can writers come up with anything truly new? Like an AT-AT Walker attack on a snow base in 1982?

Probably not. But that doesn’t mean we can’t still write movies that wow a reader or an audience.

And by my estimation, there are still two ways to do that.

There’s a way for the ultra-talented screenwriter. And there’s a way for the workhorse screenwriter.

For the ultra-talented screenwriter, the answer is A UNIQUE VOICE. Back in the 90s, concurrently with all these big Hollywood movies that were giving us stuff we’d never seen before, the indie scene was also giving us stuff we’d never seen before, but not through big expensive effects, like dinosaurs. But rather through their own unique lens. Tarantino, Paul Thomas Anderson, Spike Lee, Charlie Kaufman, Wes Anderson. They would lead us into the 2000s where we got Diablo Cody, Alan Ball, Alfonso Cuarón, M Night, Edgar Wright, and Jordan Peele. These writers showed us the world in ways we had not seen on film before.

You can’t really strategize a voice. Your voice is inherently yours so you can’t change it around. But voice tends to break out when it’s different from what we’re used to seeing. That’s the whole point of today’s article. You’re giving them something new. So if you’re writing “male romantic comedies” at a time when Cameron Crowe was the biggest screenwriter in the world, your unique voice probably isn’t going to be appreciated, since there’s already a strong voice dominating that sub-genre.

But nobody knew what hit them when Charlie Kaufman started getting movies produced. We’re in John Malkovich’s head?? What the hizell is going on right now??? Ditto Diablo Cody. We hadn’t heard heightened dialogue that fun and lyrical since John Hughes. Nobody else was doing that at the time.

Fortunately, if you’re one of the lucky lottery winners who have an industry-changing voice, you don’t need this article. You’re probably going to be okay. So let’s switch over to what the workhorse writer can do.

First off, like I said, you should still be trying to come up with new ideas. Whether it be concepts or set pieces or even an idea for a scene that’s never been done before (the opening sequence from Promising Young Woman, where the prey shockingly becomes the predator, for example). The more “new” you can get into your script – even if it’s not world changing new like an Old West bar full of aliens, you should include it. Cause all those little *slightly new* things add up.

But here’s where you should really be focusing. Because this is the hack that will allow you to write even a traditional story that people fall in love with.

The way that the workhorse screenwriter can circumvent the blueprint is to write a great main character into their script. And let me explain why. When a reader falls in love with a character, they don’t care that much about anything else but following that character around and seeing what happens to them.

This is the secret sauce that will work now and until the end of time. It is the reason why, even though we in the movie business can no longer provide audiences with things they’ve never seen before, we can still make them feel things. We can still jack into their emotional circuit board and take them on a ride that will feel just as powerful as their last relationship. That will fill them with just as much love and pain as the trials and tribulations they go through with their own family. And when they finish that ride, they will feel a much deeper connection to that film than all the CGI dinosaurs combined.

Okay, Carson, that’s great. Write a great character. Duh. That’s still really hard to do, though.

It is hard. But, at this point, it’s way more doable than trying to create something nobody’s ever seen before.

So let me give you two recent films that achieved this that you can learn from. The first was Joker. And the second was Everything Everywhere All At Once.

Joker, more than any movie in the last ten years, proved that if you focus on creating a really compelling main character, you don’t need anything else to be new. And you don’t need big fancy effects either.

The reason Arthur (the Joker) worked is because the movie made him sympathetic – someone who was picked on and made fun of wherever he went. He had a mental condition, which created more sympathy. We liked him because he took care of his mother. But also, we saw how difficult that was for him and how it shaped him (limiting his opportunities to create a social circle), adding complexity. He was an underdog in his pursuit of the pretty girl who lived in his building. So we rooted for him.

But here’s where the character took off. Cause if you stopped there, you could’ve placed that character in a romantic comedy. The reason the character becomes iconic is because he hates the world and he starts to have a severe mental breakdown. Going so far as wanting to hurt innocent people.

Severe contrast within a character (you’ve got this really good stuff and this really bad stuff swirling around in the same body) is often what makes them compelling and interesting to watch. And Arthur Fleck had that in spades. We wanted to watch him to see what he did because what he did was usually interesting.

Everything Everywhere All At Once was a completely different beast in that it was an ensemble piece and it actually was giving us bits and pieces of “new” (I mean, there’s a universe where everyone has hot dog fingers). But where the film really excels is in its characters.

The mother, Evelyn, has this really complex backstory where her father warned her not to marry this wimpy man. She ignored him and did anyway. And it turns out her father was right. Her husband never amounted to anything and, because of this, she’s 60 years old and managing a crappy laundromat that’s being held together by rubber bands and popsicle sticks.

She’s got a daughter who’s gay and it’s really really hard for her to accept that. If you slide over to the husband’s storyline, he loves his wife more than anything and is dealing with the fact that she wants to divorce him. She’s loveless. He’s hopeless. The daughter is miserable. And all of that stuff is rooted heavily in a backstory that was extensively reserached because it had to be since the movie would explore hundreds of different versions of that same backstory in other universes.

The climax of the movie is not a big fancy Marvel showdown but rather, by the Daniels’ (the directors) own admission, an “empathy fight.” It’s this family trying to connect for the first time in years.

I bring this example up because it would’ve been easy to write paper-thin characters and just focus on the fun kung-fu and multiverse gags. By making sure the characters were all complex, it turned a movie with a wacky concept into something that will stay with you for the rest of your life.

THAT’S WHAT YOU NEED TO BE DOING.

Create characters with interesting well researched backstories, who have intense unresolved inner conflict, and who also have unresolved conflict with other characters in the movie, who, to the best of your ability, you give the same fully-fleshed out treatment to.

Cause if you can write characters we love (the husband in Everything Everywhere) or are fascinated by (Arthur Fleck), those characters will get their hooks in the reader/audience, and everything else about the script becomes so much easier to pull off.

To summarize, if you’ve got that idea that nobody’s seen before, great. Write it. If you’ve got that set piece or scene that nobody’s seen before, great. Write it. As I’ve said before, producers will buy a script if it has one amazing “going to look great on screen” movie scene. If you don’t have either, try to include as much “kinda new” stuff as you can in your script. Cause it adds up. Finally, even if you don’t have a single new thing in your script, you can still write something great if you have a great main character or a cast of extremely strong characters. Unless you’re the next David Lynch, character-creation is your biggest weapon as an unknown screenwriter. Now go use it!

*********************

SPECIAL DEAL!!!!

Two script consultation slots just opened up this week. So I’ve decided to offer two SUPER-DEALS. 4 pages of notes on your feature or pilot for just $199. That’s 60% off the feature rate and 50% off the pilot rate. I know that half of you will be asleep when I post this, so here’s what I’m going to do. The very first person who e-mails me RIGHT NOW at carsonreeves1@gmail.com the word, “DEAL,” gets the first deal. And then, whoever e-mails me first starting at 9am Pacific Time tomorrow (Thursday), gets the second deal. This is a rare opportunity. If you’re someone who’s always held back because my consultations don’t fit your budget, this is the time to strike!

*********************

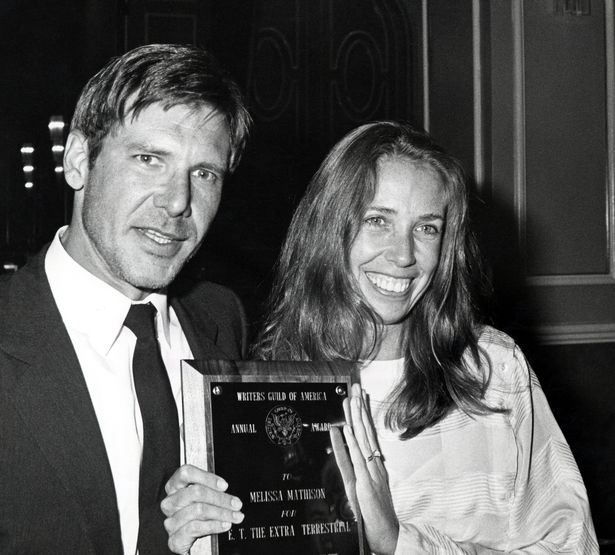

So late last month, a little known E.T. story started making the rounds. Steven Spielberg had finished 1941 and was currently on production of Raiders of the Lost Ark. Like any smart director, he was lining up his next film, E.T., and needed a writer. As luck would have it, he wanted a young writer named Melissa Mathison, who was his star’s (Harrison Ford) girlfriend at the time.

This is where the story gets interesting. Spielberg pitched Mathison the idea for E.T. and Mathison said no, she didn’t get it. I just want to pause here so we can all hear the galactic level record scratch of a writer SAYING NO TO STEVEN SPIELBERG! In Mathison’s defense, she had a good reason for the rejection. She’d just quit screenwriting.

Between her two lone credits, The Black Stallion and The Escape Artist, Mathison had decided that screenwriting was “too hard.” In retrospect, Mathison’s early retirement never stood a chance. Spielberg went straight to Ford, asked him to put in a good word for him and E.T., and Mathison eventually came around to write the film. For all involved, it was ‘happily ever after.’

However, Mathison’s reason for the initial rejection stuck with me. She quit screenwriting, at just 31 years old and with two produced credits, because it was “too hard.”

“Too hard.”

Is screenwriting “too hard?”

It sure seems easy when you’re watching a bad movie. “I could write a better movie than that!” somewhere north of 100 million moviegoers have said over the years.

But anyone who’s spent even three years in the game knows how deceptively difficult screenwriting is.

But is it too hard?

Is it not worth the trouble?

A while ago I was developing a sports script with a writer and we’d spent countless hours and many drafts trying to figure out our main character. It seemed like every new draft, we tried a new iteration of the character. After about draft 7, the character finally started to take shape. We finally felt like we understood him, and the rest of the script came together nicely as a result.

Then, around draft 10, as we were writing the big final game, it occurred to us that the ending would be MUCH BETTER if our main character made a major sacrifice at a critical point late in the game. We’re talking, the climax went from being a 6 out of 10 to a 9 out of 10. The change was a no-brainer. We had to do it.

But here was the problem. Our main character was not someone who sacrificed. Nowhere in the script was this built into the character so that when the moment came, it would make sense for him to sacrifice anything.

What we realized was, if we were to write this new direction into the climax, it would mean completely redesigning the character from the ground up. He’d have a totally different personality and demeanor. Which would make all of his actions and dialogue different.

On top of that, we’d designed the love interest to be in stark contrast to our main character. She was his opposite. By changing the main character into this new version, he was no longer the opposite of the love interest. Which meant – as I’m sure you’ve already figured out – we’d have to completely rewrite her as well! Change her from the ground up so that this new version of her was opposite to the new version of him.

So now we had to sit down and make a difficult decision. Do we make all these changes, redesigning our two main characters from the ground up, just to support this awesome ending? Or do we continue to try and find another great ending, despite the fact that we’d spent the previous six months doing just that and failing?

Is screenwriting hard?

If you’re doing it right, you bet your ass it’s hard.

So I get Melissa Mathison. I totally understand where she was coming from. Because a script can feel like a never-ending battle. In a way, you never truly write the script you want. You either run out of steam or, if you’re one of the blessed few who have made it to the professional ranks, they need to start shooting.

With that said, I have found some tips and tricks over the years to make the experience of writing screenplays a little easier. If you incorporate these ten tips, you’re going to keep more hairs on your head, and severely lower your chances of having a heart attack.

Outline – One of the things that causes so much pain in screenwriting is all the drafts. You’re always having to fix some aspect of the script with a rewrite. You can knock about 3-4 drafts off that process if you outline. In particular, outlining helps you figure out your structure ahead of time, which means spending less drafts fixing your broken structure.

Make sure you understand your 2-3 main characters as clearly as possible going into the script – The hardest thing about screenwriting is getting the characters right. That’s because people are complex and creating fictional versions of them that feel authentic takes an incredible amount of skill. Therefore, if you have a great feel for your characters going in, you eliminate a lot of headaches later on. Rocky is an underdog who doesn’t know if he has what it takes. Alan in The Hangover is the most socially unaware overly opinionated man in the universe. Guy (Free Guy) is tired of following the same old routine every day and decides he’s going to commit to doing things outside his comfort zone. Just like these examples, try and distill your character down to a single clear sentence. If you can do that, you should be good.

Keep your story simple – I read a lot of “everything-and-the-kitchen-sink” scripts where the writer is shooting themselves in the foot by giving themselves a massive amount of variables to keep track of. The reality is, most of the best movies have a simple setup and execution. Small character count. Clear goal. Etc. By keeping the variables down, you’ll keep the stress level down.

Be passionate about your concept – As much as I talk about finding the best idea you can come up with and writing it, that’s worthless advice unless you love the idea. As most of us here can attest to, there is nothing worse than writing a script you’re only kinda into. Every draft feels like five drafts. These scripts take way more out of you and will definitely accelerate any doubts you have about whether screenwriting is for you. Love that idea like you love your family.

Write lean – If you tend to write 4-line paragraphs, aim for 3 lines. If you tend to write 3-line paragraphs, aim for 2 lines. Writing lean means there are less words to edit and since we’re all writers and obsessive about making every little sentence perfect, the less words you have to wade through, the less hassle writing is going to be. As a bonus, your script is easier to read through.

Don’t deliberately make the process overwhelming – You’ve got a document detailing all the characters in your script, a document for your potential story ideas to use, you’ve got your outline, an excel spreadsheet tracking when and where every character appears, you’ve got a document for alternate scenes, a document for deleted scenes, a document explaining the alien language spoken in your script… If all these things make you genuinely happy, fine. But, at a certain point, we make the process of writing a script so cumbersome, that we start to hate the idea of working on it. It’s fine to get detailed. But don’t get carried away.

Focus on the things you should do, not the things you shouldn’t – I know reading this site can sometimes feel like a never-ending mine field of screenwriting bombs to avoid. But if all you’re doing is focusing on mistakes to avoid, you can’t write freely and you won’t have fun. You are always going to do things in your script that “shouldn’t be done,” like yesterday’s choice to make the protagonist a kidnapper. But as long as you feel it’s right for your story, embrace it and don’t look back.

Talk it out – Find someone in your life who will listen to you talk out the problems in your screenplay. One of the reasons writing is so hard is that we contain ourselves to just our brain and run the same problems through that calculator over and over and over again with no result. Of course writing starts to feel impossible (and drives you crazy!). Sometimes you need to talk your ideas out with someone, even if they’re not a screenwriter. By forcing yourself to explain the issue to a third party, you see the problem through their eyes, and that alone helps you find a solution.

Focus on the stuff that matters – Stop stressing about that exposition scene on page 70 where you’re trying to make each dialogue line perfect. Instead, focus on the things in your script that have the biggest impact on the read. The first ten pages, the first act turn, the midpoint shift, the story’s big set pieces, the hero’s low point, any major twist scene, the climax. That’s where you should be placing 75% of your focus. You don’t need to drive yourself crazy over those smaller scenes where the characters reveal some mildly significant backstory about themselves. In the grand scheme of a screenplay, those scenes are way down on the priority list.

Be easy on yourself – Screenwriting is hard no matter what you do. It’s baked into the pursuit. However, I think that’s why we do it. We know that in those few moments where we do crack the code and write a good script, we’ve achieved something amazing, something that very few people on the planet can do. Who cares if you achieve something that’s easy, right? You only feel a sense of accomplishment when you’ve achieved something that’s hard. Maybe even too hard. :)

What’s your take on this? Is screenwriting too hard?

Having concerns about your logline or screenplay? Let me help you. Logline consults are just $25 (and if you buy 4, you get a 5th for free). I also provide consultations for each stage of the screenplay journey: outline ($99), first 10 pages ($75), first act ($149), full pilot ($399), full screenplay ($499). I’ve read thousands of screenplays, including all the ones that get produced and all the ones that don’t. There’s no one better equipped to help you improve your script than me. If you’re interested in getting a consultation, e-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com and let’s work together!

Genre: Crime/Thriller

Premise: When his young son is viciously murdered by a classmate, a grieving father with a history of violence kidnaps the child responsible, igniting a frenzied manhunt fueled by a powerful politician — the father of the kidnapped boy.

About: This script made last year’s Black List with nine votes. A year earlier, it made the semi-finals of the Nicholl Fellowship. A reader from that contest characterized the script this way: “Barron’s Cove is probably the bleakest screenplay I’ve ever read. Its bleakness is only surpassed by its quality.”

Writer: Evan Ari Kelman

Details: 119 pages

Jesse Plemons for Caleb?

Jesse Plemons for Caleb?

We’ve got a wild one today.

I don’t think I’ve ever read a script quite like this.

It’s Mystic River meets Prisoners by way of Taylor Sheridan.

But it’s also a new writer. And that newness is reflected in the storytelling, which at times soars but at other times, is eye-poppingly inconsistent.

I’m still not sure what to make of Barron’s Cove. But I can promise you it’s one of the more interesting scripts on the Black List.

36 year old Caleb Faulkner is a hit man for his uncle, Benji. But Caleb isn’t one of those fancy-schmancy hit men, the kind with smooth bald heads who wear Armani suits. He’s the backwoods type – the bearded blue-collar Ozarky hit man.

One evening, when Caleb goes to pick up his son, Barron, from his ex-wife, she stares back at him with confused eyes. “I thought you had him.” After their confusion subsides, the hunt is on to find out where Barron is. The news is not good as the cops get word that a 10 year old boy was strapped to the train tracks and got run over by a freaking train. Doesn’t take long to confirm it was Barron.

Caleb quickly finds out that two kids were out with Barron that day, Alex and Phillip. And all Caleb has to do is see Alex once to know he was responsible. In one of the craziest scenes I read this year, Caleb goes to Alex’s school and chases him THROUGH THE SCHOOL T-1000 style with everyone standing around watching. He catches him, throws him in his trunk, and heads upstate.

What Caleb doesn’t entirely understand is that Alex is the adopted son of Lyle Chambers, who’s about to become a state senator. So Lyle immediately mobilizes the might of the state to find Caleb and his son.

Except it’s much more complicated than that. You see, Lyle has a backroom deal with Benji once he gets elected. So Benji is now secretly helping Lyle take his nephew down. Oh, and as Alex will later reveal to Caleb, Lyle is a serial child abuser. So Alex doesn’t want to go back to his father. In fact, the only reason Lyle adopted Alex in the first place was to make him a more sympathetic candidate.

In fact, the further down the rabbit hole we go, the more we realize that there are no clean answers here. Barron’s Cove leaves you unsure who to root for at every turn. All the way up to the heartbreaking ending.

As I’ve said north of a quarter-million times on this site, you gotta do something different with your script in order to stand out. You gotta take risks – the type of risks that get some agents and producers telling you, “You can’t do that.”

I’ll be honest, if this logline would’ve landed on my desk, I probably would’ve told the writer, “You can’t write a story where the protagonist kidnaps a child with the intent to torture and kill him.” It’s just too hard to get an audience on your side.

Kelman clearly knew this so he went into kick-the-dog mode in building the character of Alex, the kid who may or may not have killed Barron. Alex is evil incarnate. He’s just a bad kid. When Caleb first confronts him, Alex gleefully tells Caleb that Barron killed himself because he hated his father. He repeatedly antagonizes Caleb and has zero remorse for what happened.

Kelman walks that tightrope for a while, but seems to understand that you can’t walk it too far. So, eventually, Caleb starts to feel bad about Alex and his abusive father, and backs down with the threats.

Eventually they come to a truce where if Caleb can get Alex to freedom, away from his abusive father forever, Alex will tell him what happened that day on the tracks. It’s not the easiest narrative to buy into. This kid has zero leverage so it’s hard to believe he’s calling the shots. But we go along with it for the most part.

The script does a great job keeping you guessing til the end. Even though we figure out what’s happened by the midpoint, there are still several questions as to why it happened that may have been out of Alex’s hands. I really had no idea where this was all going to end, especially with the wild card that was Benji. At one point he sends hit men to kill both Caleb and Alex, and we’re thinking, “What’s going on right now?!?”

While the script doesn’t have that big splashy final twist that, I believe, it hinted was coming. It does give us a final motivation for the kill that makes sense. A satisfying ending that I didn’t think was coming as I figured the writer had painted himself into too deep of a corner.

Oh, one more thing I want to highlight here – the school kidnap scene. In my opinion, every script worth its weight needs to have ONE GREAT SCENE. You should be trying to write more than that. But you definitely need at least one. Because what a great scene does is it sticks in a producer’s head and that producer really really really wants to see that scene come to life. It very well may be the motivator for the script to get sold and made.

This school kidnap scene was great for the simple reason that the writer did something THAT HAS NEVER BEEN DONE BEFORE. Every single time there’s a kidnap scene at a school – and I’ve read tons of them – it’s always the kidnapper sneaking around the outskirts of the school, luring the kid over with a lie or the promise of something, then when no one’s looking, grabbing them and throwing them in their car.

Whenever you enter a common scenario as a screenwriter, one of the first questions you should ask yourself is, “How can I make this different?” And here’s a pro-tip for you. Your first option should be to ask, “What if I did the complete opposite of what everybody else does?” Because the complete opposite will always be jarring. The thing is, it usually doesn’t work because it doesn’t make logical sense.

But what Kelman realized here was that, for first time in history, the kidnapper was the “good guy.” Once you shift that, it opens up new possibilities for the scene that you didn’t have before. Since we’re kind of rooting for Caleb, doing the complete opposite of what a writer would normally do in this scenario actually makes sense. Which is why we get this great shocking scene. At one point, Caleb is literally chasing Alex over lunch tables with hundreds of students and dozens of faculty around. That’s going to be a great scene.

The only question with this movie is… is it so offbeat that people just aren’t going to be able handle it? Either way, it’s an entertaining screenplay. It’s different. And for that reason, I say it’s worth checking out.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: You have to be careful with writing kids like adults. I’m not talking about the precocious kids that are in every romantic comedy. I’m talking just normal kids in movies like this. There’s this tendency to bring their level of sophistication up to that of an adult to keep the dialogue sharp. Alex bordered on that a lot. For example, Caleb tells this deep intense story about being responsible for his brother’s death when he was younger. Alex – WHO’S 10 YEARS OLD MIND YOU – replies to this story with the line: “Do we have to be the worst thing we’ve ever done?” I mean come on. I’m not saying Alex needs to reply with, “Can I have a popsicle now?” But no kid has the emotional or psychological intelligence to come up with that kind of thought.

10 DAYS LEFT TO ENTER THE FIRST ACT CONTEST!

*******************************************************

What: The first act of your screenplay

Deadline: May 1st, 11:59 PM Pacific Time

Where: carsonreeves3@gmail.com

Include: title, genre, logline, any extra info you want me to know, a pdf of the act.

Cost: Free!

*******************************************************

Okay, on to more entries that failed to make the Anything Goes Amateur Showdown. The objective here is to take you behind the curtain so you can see what goes on in my head when I receive an entry. I’m hoping that by detailing the evaluation process, it will not only help the writers of these scripts improve their future loglines and queries, but help everyone here improve their loglines as well.

As always, if any of these scripts sound great, make sure to share that opinion in the comments. If something gets a ton of love, I’ll review it. Enjoy!

Title: Cheese Curls and Dirty Swimming Pools

Genre: Comedy

Logline: An elderly pool cleaner meets a naive young woman and introduces her to his world of psycho sexual deviancy and inadvertenly gets them entangled in a deadly mafia organization’s plot to assassinate a rival.

Why you should read: Anything goes? Well I think this definitley fits that description. A script 20 years in the making. Started off as a movie we actually made in high school and just kept rewriting. Funny. Dark. Strange. Twists and turns. Lets see if it all these years of working this thing can muster some laughs.

Why I didn’t pick it: This is an interesting one because the writer makes a good point. The showdown is called “Anything Goes.” That would imply that I want weird unique screenplays that take chances. Which is what Cheese Curls most definitely is. However, in doing this as long as I have, I’ve learned that while “kitchen sink” type loglines are fun, the number of writers who can actually deliver on the promise of that wackiness is miniscule. Whenever I pick one of these scripts up, they become incoherent within 20 pages. So I use the submission e-mail to decode whether this entry is an exception to the rule, or more proof of it. A few things stood out. “Inadvertenly” is spelled wrong. “Definitley” is spelled wrong. They’ve written “Lets” instead of “Let’s.” That’s three mistakes in less than a 100 word e-mail submission. That indicates a lack of attention to detail, which tells me I’m probably getting another incoherent kitchen sink mess. I also don’t like how the logline ends. A logline ending is important. Ideally, it’s the part of the logline that has the most punch. You want the reader leaving the logline thinking, “I have to read this!” Instead, the end of this logline is the least interesting part of the logline. 1) An elderly pool cleaner is a unique main character. 2) I like the contrast of a naive young woman entering into psycho sexual deviancy. 3) I’m not thrilled about the mafia element but, when combined with the other two elements, there’s potential there for an interesting clash. But then, out of nowhere, we’re assassinating some nameless generic rival. That sounds really boring and doesn’t connect to the rest of the logline in an interesting way. It absolutely destroys the logline and was the deciding factor for why I didn’t pick this.

Title: Meat is Murder

Genre: WWII / Sci-Fi-Action

Logline: The Nazis have created the Überhuman and are about to win WWII. David, a Jewish Wehrmacht soldier, who serves at the Eastern front under a false identity, must come to terms with his role as a Nazi-collaborator in order to prevent a global war of annihilation. “Django Unchained” meets “Valkyrie”.

Why you should read: What if Superman came down over the German Reich? –This script is set at the Eastern Front, told from the German perspective. The action set pieces are unique to the concept and backdrop and cannot be found in any other movie. It’s also a very weird script. In a way, I hope it’s weird enough to not be taken too seriously in the conventional sense, considering that the majority of the hideous atrocities of the Germans were committed in the East. I hope I have approached the subject matter with enough piety. Thanks in advance and kudos to everyone who participated.

Why I didn’t pick it: One of the harder loglines to write is the “mythology” logline. Science Fiction, Fantasy, Alternative Timelines, Long Ago Period Pieces. These loglines typically need you to set up the world before you tell us who the main character is, what his journey will be, and who stands in front of him. Which will often result in a two-sentence logline. Two-sentence loglines are doable. But they create challenges. You’re placing a period in the middle of a pitch that is supposed to flow from beginning to end. Because he’s dealing with the mythology issue, I don’t fault today’s writer for starting us off with, “The Nazis have created the Überhuman and are about to win WWII.” But when combined with the second sentence, there does seem to be a lack of enthusiasm to provide the reader with a clean effortless pitch. It’s clunky. And you don’t want your logline to be clunky. It implies to the reader that reading your script will also be clunky. Not to mention, the title doesn’t sound like it has anything to do with the story being pitched. That’s often a red flag. I might’ve tried to pull this logline off in one sentence: “A Jewish Wehrmacht soldier serving under a false identity must come to terms with his role as a Nazi-collaborator and prevent the German army from unleashing its newest weapon, the Überhuman.”

Title: Britt Johnson

Genre: Western

Logline: After Comanche raiders abduct his family, former slave Britt Johnson joins the Texas Rangers to bring them home.

Why You Should Read: This script was featured briefly in an Amateur Showdown on Scriptshadow. Since then, it has undergone numerous rewrites and the result is, I believe, an action-packed, gritty script that tells a story that few readers have seen or experienced before.

Why I didn’t pick it: I know. Confusing. This already made an Amateur Showdown once. So does that mean it’s an example of what’s good or what’s bad? The competition was stiffer this time around, which meant that each logline was put under more scrutiny. And this time, Britt didn’t make the cut. This logline shows you how even the simplest logline can be tricky to pull off. The first couple of times I read it, I thought the story was this: A guy’s family is abducted by Comanches. He’s able to get his family back, and now he’s going to “bring them home,” presumably traveling over a long distance where he and his family encounter many obstacles. But upon the third time reading it, I realized, “Oh, wait. He’s joining the Texas Rangers and they’re going to go to confront the Comanche, fight them, and get his family back.” The words “bring them home” did not convey that at all, which is why I was fooled. In my opinion, this is the most boring logline rendition possible for what sounds like a cool story. It’s your job as the writer to illicit that coolness in the logline. I would’ve gone with something like this… After Comanche raiders kill his son and abduct his wife and daughters, notorious former slave, Britt Johnson, joins the Texas Rangers to track down the Comanche and save his remaining family at all costs.

Title: PIZZA DELIVERY GUY

Genre: Contained action-thriller

Logline: When a suburban family home is invaded by a group of serial killers it seems certain that every captive will die horribly, but then the killers decide to order pizza…

Why you should read it: An actor who has starred in many action films read the script, really liked it, and wants to play the pizza delivery guy.Now the script is with two directors, who are currently deciding whether to become attached to the project.

Why I didn’t pick it: Our greatest strength as writers – that we live in our head – is also our biggest weakness. We often lack the ability to see our scripts, our pitches, our loglines, through the eyes of a reader who has no reference whatsoever for what we’ve put in front of them. As a result, we can’t identify what it is they may not get. “Pizza Delivery Guy” is labeled a “Contained Action-Thriller,” yet everything about the logline screams, “Goofy Comedy.” When I can’t match up the logline to the genre, I take the easy way out and move on to the next submission. In other words, if you’re going to pitch your story as an Action-Thriller, the logline should read like so. Also, this logline needs more information. “…but then the killers decide to order pizza…” can literally lead to 10 million different scenarios. The pizza guy shows up and… what? What does he do? This is, presumably, going to be 75% (or more) of your movie. You can’t leave that much of your movie unanswered in the logline. This is why writers need to get logline feedback. You’re shooting yourself in the foot.

Title: BREAKOUT

Genre: Thriller

Pages: 86

Logline: When a young woman is sealed inside her estranged Father’s property and outnumbered by intruders, she has no choice but to go deeper inside both the house and her past if she wants to get out alive.

Why You Should Read: This script was a semi-finalist in last year’s Final Draft Big Break contest. So per Carson earlier this week, is this a sign I should start looking for houses in the hills cause I’m about to hit it big?

Why I didn’t pick it: This script was one special attractor away from getting picked. What’s a “special attractor?” That’s the unique x-factor in your concept, the thing that separates it from everything else. It’s a family living silently in a world where monsters attack through sound. It’s a dinosaur theme park. It can even be a fairly new addition to popular culture, like the panic room was back in 2002, when David Fincher made the Jodie Foster contained thriller. Going “deeper inside a house” is just a fancy way of saying, “running around a house.” It doesn’t provide us with anything new or fresh in the genre. That’s not to say the script isn’t any good. You might have nailed the character development. But this is why flashy concepts are so valuable. They get more people wanting to read your script! The less flashy the concept is, the less people will want to take a look. It’s as simple as that. Either way I would encourage the writer, Kim, to get a logline consult if there’s more to this story, or get feedback from the community. Cause if the script is good enough to make the semi-finals of a contest, you need a logline that’s going to get more people to read it.

Title: In the Cold, Cold Night

Genre: Murder/Mystery/Whodunnit

Logline: With the world on the brink of a biblical apocalypse, a loose cannon alcoholic in a small Texas town tries to solve an old murder case to exonerate the primary suspect, her father, before the end of days.

Why you should read: It explores the hypocritical Texas towns I grew up in where religion is the only thing that matters and shitty people are considered saints just because they go to church on Sundays. This is a gold star example of writing what you know. It got an 8 on the Blacklist with a first draft in which the reader said “An impeccable sense of atmosphere and a compelling mystery put this script in good company with prestige shows like True Detective and Sharp Objects.”

Why I didn’t pick it: Getting an 8 on the Black List isn’t easy to do. And just from the way the writer communicates, I get the sense that this could be good. It’s been a while since I evaluated this entry, but I think the reason I passed was because the movie’s setup invites a great big, “So what?” to the primary objective of the story. Who cares if you exonerate your father if the world’s about to end anyway? It’s like me writing a movie called, “Go For The Gold,” about an aging runner who tries to win the Olympic 40 yard dash a day before aliens come and destroy the planet. Sure, he won the gold but… why did it matter exactly? I still think this script could be good but that’s why I chose not to feature it.

Title: The Boneyard

Genre: Thriller.

Logline: A purveyor of serial killer memorabilia must crack a case of missing murder victims to save his kidnapped daughter while hounded by the FBI as the main suspect.

Why You Should Read My Script: This is a gripping, edge-of-your seat thriller with a solid three-act structure, a twisty and complex plot moving the story along at a good pace, with a ticking clock, and life-and-death stakes from start to finish.

Why I didn’t pick it: This submission reads like it was constructed out of a bunch of buzzwords and buzz-phrases. “Serial killer memorabilia.” “Crack a case.” “Missing murder victims.” “Save his kidnapped daughter.” Even the WYSR sounds this way. “Edge-of-your-seat.” “Solid three-act structure.” “Complex plot.” “Ticking clock.” “Life-and-death stakes.” “From start to finish.” The title suffers the same fate (“The Boneyard”). Your script is not going to be celebrated for all the things that it does that are familiar. It’s going to be celebrated for all the things about it that are unique, that stand out. So if you don’t have anything unique to offer, your script is going to sound generic, which is how this sounds. When it comes to loglines, identify what it is that’s unique about your idea and BUILD THE LOGLINE AROUND THAT.

Title: Science vs Romance

Genre: Sci-Fi/Romance

Logline: When a burnt out screenwriter is hired to help fix the world’s first simulated reality program she inadvertently jeopardies existence by falling for the subject.

Why you should read: I’ve been writing scripts for a few years now but mostly thrillers, I thought for this contest I’d send the one script where I took a real chance and tried something really different (for better or worse).

Why I didn’t pick it: This logline fails for the simple reason that, after you read it, you’re not entirely sure what the author meant. A writer is hired to fix a simulated reality program. So far, so good. She then jeopardies (I’m assuming we meant jeopardizes) existence by falling for the subject. By “existence” are we talking about the simulated existence or actual existence? If I’m to take the logline literally, I’m assuming actual existence, although I don’t know how diddling around with a simulation program would affect reality. And this “subject.” What subject? What does that mean? One of the fake people inside the program? Or maybe the creator of the simulated reality? It’s anyone’s guess because it definitely isn’t clear. I don’t think you guys realize how common this is. I get submissions like this all the time where I don’t 100% understand the idea so it’s easy to say no. Get your loglines looked at ahead of time so you don’t make mistakes like this!

Title: BLACK MOLD

Genre: Sci-fi/Thriller (TV pilot)

Logline: A lonely Korean janitor exposed to an interdimensional spore that enables her to see aliens mimicking people must hunt for the key to prove her sanity and save the world from total hive-mind colonization.

Why you should pick: If titles like THEY LIVE and MIMIC make you salivate, but you’re looking for something more, imagine a world in which only a handful of people have discovered the majority of humans around them aren’t humans at all, but are masquerading aliens bent on enslaving the human race, but then imagine that all this is taking place in a version of reality that was split off from ours back in 1978, and there’s only one way to reset Reality itself back to what it was before the aliens arrived: by exploding a nuclear bomb outside of Las Vegas. Combining quantum physics, alien body-mapping tech, hallucinogenic digital mold, conspiracy theories and one cantankerous Korean lady with an axe to grind, Black Mold may just be your cup of miso soup.

Why I didn’t pick it – I went back and forth on this one. If it was a feature, I probably would’ve chosen it. As I like to remind everybody, pilots are eligible for Amateur Showdowns. But they have to be twice as good to get chosen. I will say that the more I read about this story (in the “Why you should pick” section), the more leery I became. The second you say that this secret alien race angle is spun off from a different timeline back in 1978, I immediately move this over into the “too complicated” folder. True, it’s different. But it doesn’t feel organic. It instead feels forced. Whenever I come across creative choices that feel forced, I always pull away. With that said, it’s a TV show. Which means you have more time to lay the foundation of the mythology before moving on to some of the wilder creative twists. So maybe this makes sense when it plays out over four seasons. But it’s a lot to take in in a single 150 word pitch. “Black Mold” is a good glimpse into how people assess ideas. You often go back and forth and back and forth on whether to choose something, and if there’s any hesitation at all – about a character, about the plot, about a creative choice – you use that as a reason to pass. Not because you’re an evil person who hates writers. But because you only have so much time in the day and there are many more scripts to get to.

Title: Empathy In An Uncanny Valley

Genre: (Sci-Fi, Drama, Thriller)

Logline: A robot detective that believes in God has sex and vapes seeks help with mental health issues from a police psychiatrist.

My Reason: I think you should read my script because of the logline! A religious robot that has sex and vapes; now that your mind is in the gutter — you know you wanna read it!

Why I didn’t pick it: I really wanted to pick this because the writer, who’s also a director, is starting to have some success and seems like a really cool dude. And the script sounds unique. But the logline isn’t giving me enough. Think of it from my perspective. I’ve just read this logline, right? What is the movie I’m imagining from it? A robot walking around vaping, sometimes having sex, and then having long drawn out therapy sessions with a therapist? Where’s the plot? Where’s the goal? Where is the bigger objective? One of the things I always say if you’re writing a small character-driven story where the focus is more on the internal than the external, is throw in a dead body somewhere. A murder. It gives your story instant pop and direction (someone’s going to have to investigate that murder – your protagonist could either be the investigator or the investigated), yet it still allows you to do all that character introspection that drew you to the idea in the first place. But if all you’re going to do is have a character walk around and do normal everyday things, most audiences are going to tell you that’s not enough.

Having concerns about your own logline? Let me help you with it. Logline consults are just $25 (and if you buy 4, you get a 5th for free). I also provide consultations for each stage of the screenplay journey: outline ($99), first 10 pages ($75), first act ($149), full pilot ($399), full screenplay ($499). I’ve read thousands of screenplays, including all the ones that get produced and all the ones that don’t. There’s no one better equipped to help you improve your script than me. If you’re interested in getting a consultation, e-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com and let’s work together!

Did another franchise just bite the dust? Combined with the WB-Discovery merger, does this mean even MORE superhero movies?

Don’t worry all you muggles.

I’m not here to bash your favorite franchise for its poor showing at the box office (Fantastic Beasts = $43 million). But it appears that this latest Dumbledore excursion was more like a Dumble-BORE.

I shall instead use this as a teaching moment. Writing good movies is a backbreaking endeavor that even Professor Minerva McGnagall would have trouble enduring. When you have seven 500 page books to mine stories from, chances are they’re going to be good. But if you’re trying to mine the same number of stories from a single 120 page book…. Well, I’m sorry, but it’s probably going to go the way of Avada Kedavra.

Let us remember that the primary reason book adaptations tend to do well is that the screenwriter has so much to draw from. Once you throw out that formula, expect bad things to happen.

It’s why I like to remind writers that a spec screenplay is drawn from nothing. You are conjuring up words, characters, mythology, and backstory from a giant bottle of bupkis. It’s why I encourage you to learn as much about your world and characters as possible before you write because how are you going to compete with someone who has an endless slew of character backstories when all you know about your main character is that he’s kind of a jerk?

WB’s meteolojinxian misfire comes on the heels of the company merging with Discovery, who promises to reevaluate the movie catalogue at the company, including DC. I have to say, apropos of nothing, that I’m confused how the company built off of 90 Day Fiance has more sway than an iconic 100 year old movie studio. Do we really live in a world where Big Ed is a bigger deal than The Joker? Either way, Discovery has implied more ‘shared universe’ stuff is ahead for DC, and less muggles and snuffledores.

Join me in campaigning WB-Discovery for a Big Ed – Joker crossover!

Join me in campaigning WB-Discovery for a Big Ed – Joker crossover!

I’m 100% in agreement with this approach. I’ve always found DC’s strategy of making random unrelated superhero films to be bizarre. I know their initial attempts at a shared universe failed. But that had less to do with it being a bad idea than it did with putting Zack Snyder in charge. If I need a dreamy CGI backdrop to a badly written movie, I’ll go to Snyder. If I need vision, scope, and a plan??? I have about 700 people in Hollywood I’m calling before him.

One of the properties Discovery is so miffed about is Superman. He’s the most popular superhero ever and they don’t even have him in the production rotation. On the surface, they’re correct. You’d think Superman would be the centerpiece of any comic book movie plan.

But the deeper you delve into the character, the trickier you realize he is. For a screenwriter, the most compelling Superman story is his origin story, cause it’s so fun. But everyone knows that story so you can’t make a movie of it. The next most compelling story is the “Death of Superman.” And they tried to do that to middling results. Snyder also tried to turn him into a tougher darker “Batman” like character. But that didn’t work because it wasn’t Superman. So what do you have left? I honestly don’t know. You need someone with a crazy cool take and there aren’t many people out there who are capable of coming up with that take. Maybe Christopher Nolan? Taika Waititi? JJ Abrams. Problem is, everyone wants these guys. So good luck getting them. Speaking of, I’d like to see a Daniels’ Superman, lol. How awesome would that be?

I want to know what’s going on with JJ. WB snatched him up for giganto money and we haven’t heard a peep from him since. Did they lock him inside a mystery box in the Warner Brothers basement?

He was supposed to shepherd the promising sounding “Justice League Dark” line of characters, which includes Constantine, Swamp Thing, Pandora, and the Phantom Stranger. Newer, fresher, superhero characters who could provide a jolt to the stagnant DC slate. Alas, we are yet to see these characters materialize.

I suspect JJ is still traumatized after Rise of Skywalker, his last film. I was able to get some inside information that JJ was devastated by the final cut of “Rise,” which included numerous things that he did not approve of. I think that experience has made him gun-shy to direct again. So I’ll make my personal plea to JJ here. JJ! You know I love you! Come back! Make movies again!

In the meantime, I’m trying to find something, ANYTHING, to watch. Severance (Apple TV) is good yet I’m not sure the central mystery is powerful enough to get me to the finish line. I stopped watching during episode 3, figuring I’d get back to it soon, but never did.

I like the mood and tone of this new show, Outer Range, on Prime. But I’m not convinced cowboys and aliens are a good marriage. The most interesting thing about this show is how similar it looks to Jordan Peele’s “Nope,” another alien-cowboy hybrid. It never ceases to amaze me how even the most original ideas aren’t as original as you think. Everybody’s drawing inspiration from the same stew. That’s why whenever someone claims somebody stole their idea, I roll my eyes. Nope. You’re just not as original as you thought.

Moon Knight is another show I started but haven’t gotten back to. I’m realizing with these ‘event’ shows, there’s a formula. They spend a ton of money on the pilot episode then have no money left over for the second episode. Moon Knight’s second episode is one scene after another of two people talking in a room. My interest dove from an 8 out of 10 (the pilot) to a 3 out of 10 (second episode). And I haven’t been able muster up the energy to get back to it.

That’s a weird thing to say: I find it hard to press a remote control button to enjoy a FREE high production value TV show. But this is the entertainment environment of 2022, a sort of “TV FOMO” where there are so many shows that whenever you watch one, you figure you’re missing out on another. Or, at the very least, there’s gotta be some other show that’s better than the one you’re watching, right? That’s been my experience lately. I keep thinking, “I vaguely remember there’s some show I should be watching. Where is it again?” That thought alone can get me to turn off the current episode of Moon Knight, Severance, or Outer Range.

I checked out feature film, “After Yang,” on Showtime Streaming. As most of you know, I’m a huge Kogonada fan, who directed one of my favorite movies from 2017, Columbus. I also love his directing story. He was a film critic for years and decided, in his 50s, to start directing himself. It’s a reminder that it’s never too late to give this career a shot!

Unfortunately, After Yang is storyless. There’s no screenplay here. After starting out with an amazing visual of several families dancing to a networked video game workout, the movie never identifies any sort of driving narrative. There is a goal – a family’s android helper breaks down and they try to fix it – but the stakes are below sea level. You never get the sense that it’s that important they fix Yang. And the casualness with which the father character, Jake, goes about the journey, gives the story a laissez-faire attitude that, quite frankly, puts you to sleep.

While Kogonada thrives with slower-paced deliberate material – that’s what was so great about Columbus – this story is begging for more urgency and importance. The implications of why the family’s android conked out appear to be large. So nobody caring all that much whether they fix him or not creates a confusing message.

I’m not giving up on Kogonada, though! He directed four episodes of the Apple TV series, Pachinko, which chronicles the hopes of a Korean immigrant family across four generations. Did I just say I was gonna watch a period Korean drama? Hell yeah I did. Only fellow members of the Kokonuts fan club understand what I’m talking about. Kokonuts, unite!

I was going to see Everything Everywhere All at Once this weekend but I came down with a cold and didn’t want to be a cold superspreader. Even if I was okay, though, I still would’ve huffed and puffed at spending 20 bucks on this film. As much as I admire A24 for bucking all logic and refusing to cater to the new demands of the industry, it’s hard for me to justify seeing an independent film in the theater these days. I love the Daniels. And the movie’s doing pretty decent so far ($17 million total). But I wish they would’ve premiered this on a streamer and spent a ton of money promoting it as a big event. It’s got streamer written all over it.

It may sound like I have no hope for the future of entertainment but that would be incorrect. My hope rests with YOU! More specifically, your first acts. My First Act Contest deadline is just two weeks away (May 1). So keep sending those entries in! Also, if you need help on your logline, e-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com with the subject line “CONSULTATION.” Logline consults are just $25!

THE FIRST ACT CONTEST

I need your title, genre, logline, anything you want me to know about the script, and, of course, a PDF of your first act. You want to send these to carsonreeves3@gmail.com with the subject line “FIRST ACT CONTEST.” The contest is 100% free.

What: The first act of your screenplay

Deadline: May 1st, 11:59 PM Pacific Time

Where: carsonreeves3@gmail.com

Include: title, genre, logline, extra info, a pdf of the act.

Cost: Free!