Search Results for: F word

“Cosmic Sunday, wake up in the late afternoon! Call Parnell, to see what he’s doin…!”

Genre: Sci-Fi/Time Loop/Comedy

Premise: A small percentage of the population is stuck in a time loop and have had to create a society that functions within the same day, repeated day in and day out. One man struggles to find himself for the first time in ages amidst a society clinging to a sense of normalcy.

About: This is MacMillan Hedges’ second time on the Black List. The first was for “The Searchers,” an exploration of John Wayne and John Ford’s unique relationship on the set of the famous film.

Writer: MacMillan Hedges

Details: 110 pages

Yesterday I announced the countdown to Sci-Fi Showdown. What better way to blast things off than with a sci-fi script? That is, of course, if you consider loop movies “science-fiction.” I know some of you out there are getting bored of loop scripts. Dare I ask you this then. Are you bored of roller coasters? Cause they have loops. And last time I checked there are plenty of them still delivering thrills and chills around the globe. “Bored of loops.” How dare you.

29 year old Bill Button wakes up in his parents’ house for Thanksgiving, walks downstairs, punches his Uncle, then goes to work, one of those stale glass office buildings with between 5-15 floors.

Co-workers tell Bill they heard all about his wild day yesterday, where he drove a bus full of children off a ledge to their fiery death. We’re not quite sure what’s going on yet but a picture is starting to form.

Bill, along with everybody else in this office, is part of a group called the AWAKES. They’ve been stuck in a time loop for 74 years. There are also people – people who live all around them – called STUCKS. The Stucks are unaware that they are also in a time loop.

I think an entire 1/12th of the world is AWAKES. More on that later.

Bill is trying to make it through each day without killing himself. Except for Sunday. Sunday, or “Cosmic Sunday” as its known to Awakes, is the day of the week where you’re encouraged to do anything you want – kind of like a “Loop Purge.” According to upper management at Bill’s work, Cosmic Sunday keeps you sane.

On a typical Sunday, for example, Bill will lace himself up with C-4 explosives, head over to the local Six Flags, stand in front of the ferris wheel, then blow himself up. Why Bill gets so much joy out of killing himself in front of children is anyone’s guess. But as he points out to a concerned upper management office worker – “What does it matter? They’re all going to forget by tomorrow.”

One day downtown Bill spots a raving madman screaming that there’s a way out of the loop. Bill can finally become a “Stuck” again. That is, assuming, that the guy is telling the truth. Which is anything but a guarantee considering everyone in this reality is going insane (if they haven’t done so already). Will Bill get out? Does he really want to get out? Or has the loop become the only way he can exist?

When they first wrote Groundhog Day, it was originally supposed to start in the middle of the loop. But after reading that version, producers decided it was too confusing and it would be better to start the loop at the same time as the main character.

Since then, audiences have become more familiar with time loop movies, a shorthand has developed, and therefore it is more acceptable for loop films to start mid-loop. We saw this most prominently with Palm Springs, where we started thousands of years into the loop.

Cosmic Sunday, however, shows you why those original Groundhog Day producers were so concerned. When you’re thrown into a loop, you’re not sure what’s going on. And if the loop ruleset is complicated, you’re REALLY not sure what’s going on. The big difference between Cosmic Sunday and Palm Springs is that Palm Springs only needed to keep track of two people. Cosmic Sunday needs to keep track of 1/12th of the world’s population.

I think.

The fact that I don’t know for sure is evidence that this script is way too complicated. I originally thought that only the people who lived in Saratoga Spring were stuck in the loop. But then I noticed there were plenty of people in Saratoga Springs who weren’t stuck in the loop.

So I thought, hmm, okay, maybe these are people who live outside Saratoga Springs but who are visiting Saratoga Springs for the day. Hence, while they’re not affected by the loop, they are around people who are. But then halfway through the script, we get this semi-vague line about how 1/12th of the world’s population is stuck in the loop. Which means about 750 million people throughout the world are having to pretend to not be stuck in a loop.

Just trying to work that out mentally hurts my head.

There’s a bigger note here about science-fiction rules that everyone planning to submit to Sci-Fi Showdown needs to keep in mind. You need the rules of your science-fiction story to be clear. If they’re not, the reader will always be reading your story through a foggy haze. They’ll only understand about 75% of what you’re putting down. And for anyone who’s watched a messy movie, you know how that feels. You *kind of* understand what’s going on. But not really.

It’s basically the difference between The Matrix (clear rules) and The Matrix Revolutions (messy rules).

Even the labels in Cosmic Sunday don’t make sense. The people who know they’re in the loop are referred to as “AWAKES” and the people who don’t know they’re in the loop are referred to as “STUCKS.” But shouldn’t it be the opposite? The people who know they’re in the loop are the ones who are “STUCK” in a loop. It just feels like we could’ve come up with a better working vocabulary.

And I still can’t wrap my head around 1/12 of the world’s population secretly hiding from the rest of the world that they’re in a loop. There seem to be laws that force you to keep the loop a secret from the Stucks. Except for on Sundays, when you can drive a bus full of children off a ledge and into a fiery death. If the non-loopers are going to forget everything tomorrow, then why not do whatever you want every day? Someone actually asks this question in the script and we get a shaky answer. Something about how loopers will stop finding meaning in life if they do that.

I guess that kinda makes sense but… again… only kinda.

This is not to say I don’t think the writer thought hard about the rules of his universe. There are plenty of examples where you can tell he has a solid understanding of what living in this bizarro universe is like. When two “AWAKES” go out on a date, for example, it isn’t a normal date. It’s the craziest date ever. In one instance, Bill and his date reenact the Honey bunny diner scene from Pulp Fiction, shooting several people dead in the process. That brazen recklessness makes sense to me considering the circumstances.

But I think Hedges bit off more than he could chew. No matter how much you try to understand the rules governing this world, there are way more questions than answers. For example, presumably, the people “STUCKS” kill on one of those dates – their families and friends move on to the next day. Therefore, those families and friends are living the rest of their lives mourning the loss of a family member to a brutal diner murder. Why is that okay for AWAKES to do then? Ditto the mothers and fathers of those kids who died on the school bus.

Hedges would’ve had an easier time if he’d limited the loop to this one town of Saratoga Springs. But I give him props for finding a loop concept that hasn’t been done before. Cosmic Sunday is definitely different from every other loop script out there and if you’re looking to read something different, check it out.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: “It’s” always equals “It is.” The only time you ever use “let’s” is when you’re saying “let us.” For everything else, use “lets.” “Who’s” equals “who is” or “who has.” For everything else, use “whose.” “You’re” always equals “You are.” For everything else, use “Your.” If the word that follows “a” starts with a vowel, you change it to “an.”

Plus, the quickest and easiest strategy to get your script on the Black List.

Frequently, I see comments or receive e-mails regarding all the bad reviews I give to Black List scripts. Readers of the site are confused by the mixed messages. These are, supposedly, the industry’s best scripts! Why, then, are they getting such poor reviews??

There’s a lot going on with the answer to this question so bear with me. The first thing you have to understand about the Black List is that it has too many scripts on it. There were 80 scripts on the 2020 Black List. There’s just no way there are 80 strong screenplays in a year. The Academy Awards has 5-10 movies on its “Best Films” nominated list. Imagine if 80 movies were on that list. Do you think all of them would be good? Half of them? Of course not. So to think we have 80 awesome scripts floating around town each year is silly.

For this reason, you can lop half the scripts off the list right away. The Black List would be better off being more exclusive and only celebrating, say, the top 25 scripts each year. If they did that, the reviews on this site would be a lot different.

Another thing to keep in mind is that many of the scripts on the Black List are not from professional working writers. There are a few reasons for this but one of the big ones is that when you’re an agent/manager trying to get your new client’s script sold (or get them some work), you’re blasting it out to as many people as possible. In the process of doing that, the script gets a lot of exposure. So when it comes time to vote at the end of the year, it’s likely that people will remember that script, even if it wasn’t very good.

Meanwhile, if you’re an already established writer with a half-a-million dollar quote developing something for Ridley Scott, the only people seeing that script are you, Ridley, and Ridley’s two most trusted producers. So when it comes time to vote for the Black List, how is that script going to fare when only 3 people have read it and none of them vote for the Black List?

Now, every once in a while, one of those tightly-developed scripts will leak out, and if it’s good, people will pass it around. As word of mouth builds, more and more people want to read it. That way, when Black List voting comes around, the script gets votes even though it was never officially sent out by an agent or manager. We saw this with Aaron Sorkin when his script, The Social Network, did well one year.

However, by and large, people never see the scripts the industry’s top writers are working on, or even the industry’s middle tier screenwriters are working on, most of whom are probably writing better screenplays than what’s on the Black List.

Another complication that’s thrown a wrench into things is the agency exodus. A couple of years ago, writers left agencies over TV packaging deals and what we found out is that agencies drove a ton of good writing content into the system. Without them pushing scripts, that onus has been placed on managers. And while there are managers out there who know good writing, they can’t make up for the loss of WME, CAA, and UTA.

I’ve seen a NOTICEABLE drop in quality in the 2019 and 2020 Black Lists, which is why you’ve seen so many negative Black List reviews on Scriptshadow over the last two years.

The truth about The Black List is that it mainly celebrates new writers who are still raw but have just enough talent to secure managers. Those managers send their scripts out. And if they’re a big manager with a big reach, their scripts will make the Black List, if not based on quality, then based on exposure.

Let me make something clear. I still think there’s value in making the Black List. It gets you exposure. A lot of scripts on the list end up getting made. And even if your script doesn’t get made, you tend to get assignment work from it. We’ve highlighted this a couple of times this week with Michael Waldron, who made the top half of the Black List several years ago with “The Worst Guy of All Time And The Girl Who Came To Kill Him.” That script resulted in him becoming one of Kevin Feige’s most trusted writers. I don’t think that happens without the Black List.

And the good news is, this gives us a pretty clear path to making the Black List. I’ve told you who the most influential people are for getting scripts on the list – MANAGERS. Therefore, you should be writing for managers. Okay, Carson, but what do managers like? I’ve already told you. They like having scripts that end up on the Black List. Those scripts get their writers work one way or another, which means they (managers) get paid.

Okay, Carson. But what scripts does the Black List like?

The answer to that question changes every few years but I can tell you that, lately, the Black List is leaning more into “message” scripts, kind of like what the Nichol and the Academy do. More specifically, it favors biopics (Gusher, Bikram), people of color persevering (Chang Can Dunk, Two Faced), LGBTQ themed scripts (Forever Hold Your Piece, Occupied), quirky scripts (Bubble & Squeak, Birdies, Possum Song), scripts that espouse liberal values (State Lines, High Society), and true stories (Neither Confirm Nor Deny, Enemies Within).

Genre scripts can make the list. For example, “Emergency,” “Video Nasty,” and “The Culling” all made the list. But these are not the scripts that the Black List would prefer to celebrate.

Now it’s important to note that just writing an LGBTQ script isn’t going to get you a manager. The script still has to be well executed. That means you need a good concept, a strong memorable main character, a clear understanding of the 3 Act structure, a good grasp on GSU (goals, stakes, urgency), and an understanding of how to escalate a story and bring it to a satisfying climax.

Naturally talented writers take about 5-6 screenplays before they get to this level. Less talented writers take anywhere between 7-15 screenplays before they reach this level. If you have little talent, you can still get there by becoming a “workmanlike” screenwriter who makes up for his lack of talent with an unparalleled understanding of storytelling (you know the intricacies of character arcs and dramatic irony and the 50 different ways to add conflict to a scene, etc). But it takes a lot longer.

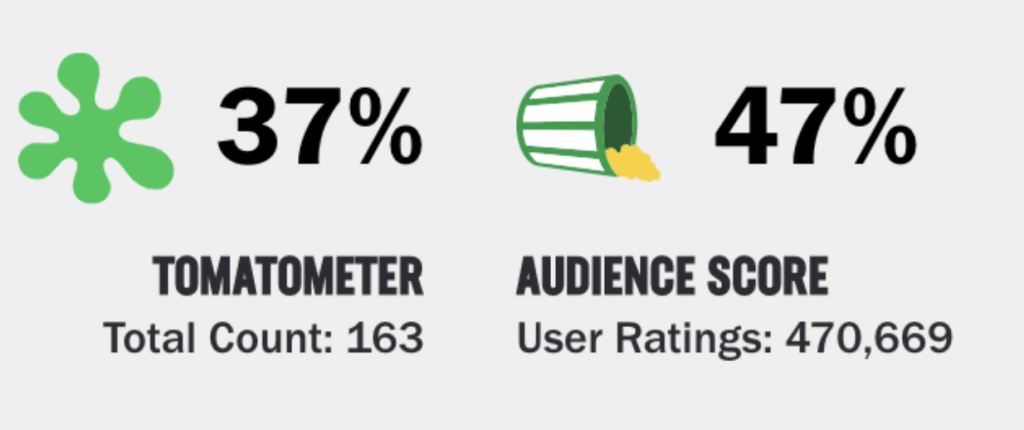

This is all well and good, Carson. But how do I know where I am? Or how close I am? Well, let’s look at things on a 1-10 scale. The average script that makes the “Top 5” in one of my Showdowns, is a 5 out of 10 script. The bottom half of the Black List consists of, mostly, 6 out of 10 scripts. The top half gets a lot of 7 out of 10s. And when you’re talking about 8, 9, or 10 out of 10, you’re talking about working screenwriters with actual credits.

In other words if you make a Scriptshadow Showdown, you’re very close to making the Black List. You’re only one level away. And, of course, there are plenty of exceptions to this rule. Sometimes a Black List script ends up being a 9 out of 10. Sometimes a professional screenwriter writes a crappy script that tops out at a 5 out of 10. And sometimes a Scriptshadow Showdown produces an 8 out of 10 script, which has happened a handful of times.

These aren’t hard and fast numbers here. But they act as general guidelines as to where you are on your journey. By the way, there’s nothing wrong with ignoring all this noise and writing what you’re passionate about then seeing where the chips fall. That’s a strategy that’s broken a lot of people into this industry. But if you want to be more tactical about it, writing the type of script that both managers and the Black List likes may improve your chances of breaking in.

Your final question is probably: WELL HOW THE HELL DO I GET A MANAGER? Here’s what I would do if I were you. First, download the 2020 and 2019 Black Lists. Under each script, they list the manager (and management company). Write down all those managers/companies, then go get a 7-Day free trial on IMDB Pro, plug all those names into their search engine, and it will give you their contact information.

From there, you can go ‘targeted’ or ‘blanket.’ For “targeted,” only query managers who represent Black List scripts similar to your own. For “blanket,” query every damn manager on the list. In both cases, keep the query simple. Include a brief introduction and your logline. If they like it, they’ll request your script. It’s as easy as that.

And if you want help, I offer plenty of services to help you. I have a logline service for $25 that includes a quick and dirty 150 word analysis and a logline rewrite, a more involved logline service for $40 where we both work on the logline together, and a $50 service for e-mail queries. I know a lot of these managers so I have a good feel for what they’ll respond to. E-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com with the subject line “CONSULTATION” if you’re interested. :)

Today we review the oddest concept on last year’s Black List, all to get ready for December’s “Weird Script Showdown!”

Genre: Fantasy/Sci-Fi

Premise: A young girl creates a robot version of Harry Potter while her father simultaneously is treating Harry Potter star Daniel Radcliffe for a terminal disease.

About: This script finished on last year’s Black List with 10 votes. The brand new writer, Monisha Dadlani, is repped at Verve and managed at Good Fear.

Writer: Monisha Dadlani

Details: 111 pages

23 years ago a writer named Charlie Kaufman took over Hollywood with a screenplay titled, “Being John Malkovich.” It was about a guy who found a porthole into John Malkovich’s mind. This began the “Charlie Kaufman Era,” an era that included half-a-dozen weird concepts with even weirder executions. Whether you liked or disliked Kaufman, you couldn’t deny that he was unique.

There hasn’t been a whole lot of weird stuff since that era. Occasionally we’ll get films like “The Lobster” and “Sorry to Bother You.” But the thing that made early Charlie Kaufman stand out was that he understood character so well. That and he added just enough familiarity to the premise to make it accessible to larger audiences.

Anybody can write a movie about a guy who walks around in an armadillo suit who’s pursuing his dream of becoming an opera singer. In other words, anybody can come up with a weird nonsensical concept. It takes talent to come up with a strange concept that people can relate to and enjoy.

Such is my desire when announcing “Weird Script Showdown” for the end of the year. Just to remind everyone where we are at the moment—

This Thursday is the deadline for COMEDY SHOWDOWN, where the five best concepts will be featured to read on the site this Friday. (MAKE SURE TO COME BY THE SITE THIS WEEKEND, READ THE FINALISTS, AND VOTE!!!)

The next showdown will be Sci-Fi Showdown. That deadline will be mid-September. More information on that coming.

And then, this December, I want to do something different. I want to do a showdown for weird script ideas. Bring back that spirit of a young Charlie Kaufman.

Which is why I’m reviewing today’s screenplay. This is the kind of concept I’m expecting to get for Weird Script Showdown. And I thought it would be fun to figure out what the challenges are for weird script ideas like this. Let’s take a look.

The year is 2057. 13 year old Myra Gupta is a huge Harry Potter fan. Her best friends, Eva and Riad, are *also* huge Harry Potter fans. But you know what they also are? SECRETLY DATING. That’s right, Eva and Riad announce to Myra that they’re going steady and Myra is devastated because that means the entire dynamic of their friendship has been destroyed.

Across town, a 68 year old Daniel Radcliffe is doing a stage version of one of the Harry Potter books when he has a stroke. He’s rushed to the hospital where his doctor, Dr. Pravit Gupta, Myra’s father, informs him that he has a very rare disease called Kutain’s Disease and he’s only got 3 months to live!

Back in the Gupta household, Pravit doesn’t tell Myra about Daniel, even though he knows she’s a huge Harry Potter fan. But that’s okay because Myra has a new mission after losing her friends. She’s going to build a robot version of her dead mother, who, by the way, also happens to have died from Kutain’s Disease.

After Privat tells Myra that recreating mom is weird, Myra gets a new idea – let’s make the robot Harry Potter! After a week of work, Daniel Radcliffe, as in Old Man Daniel, stops by the house to talk to Privat. Myra comes downstairs with her Harry Potter robot, who meets Daniel Radcliffe! The Harry Potter robot immediately starts downloading all of the Radcliffe information in front of him, making him even more like Harry.

Initially weirded out by the Harry Robot, Daniel starts to like him! And they start hanging out together. As the robot becomes more like Harry every day, he starts concocting spell-laden drinks for Daniel to drink, which begin to cure Daniel! Will Robot Harry Potter be able to save Daniel Radcliffe? Or is Daniel doomed no matter what? Sounds like a question only the House of Gryffindor can answer.

One of the things you’re trying to do with these weird ideas is the same thing you’d do with any idea – create a moment/scene/scenario, early on in your story, that emotionally connects your audience to your hero. Because once the audience is emotionally connected to the main character, we’re more willing to go along for the weird ride.

Early on, Myra learns that her two best friends have become a couple behind her back. While not everyone has experienced this exact scenario, we can all sympathize with someone who, suddenly, feels betrayed and alone. Before this moment, I didn’t care about anything that was happening. But after this scene, I was in.

That writing approach, by the way, will always serve you well. If you’re constantly looking for ways to connect the characters and the audience, readers/viewers are going to get more and more attached to the characters. At a certain point, it doesn’t matter what the plot is. We want to see how each characters’ journey ends.

And make no mistake, this is a weird journey.

It’s 2057. Daniel Radcliffe is doing Harry Potter plays in his late 60s. We’ve got rare diseases we’ve never heard of. We’ve got someone building a robot. We’ve got multiple scenes of Robot Harry Potter and Dying Daniel Radcliffe dancing with each other.

If you look at these elements in a vacuum, you’re thinking they won’t work.

But I cared about Myra. She was an easy character to like. She loses her friends. She’s lost her mom. She’s creating a robot so she’s not lonely. That’s the emotional core of the movie and what we care about.

If I was producing this movie, I feel like I could get the same result with a much less complicated plot. Less moving pieces. But that’s where the “weird script” debate gets interesting.

There’s a component to “weirdness” that doesn’t require logic. When you’re writing weird scripts, you’re following your gut more than your brain. So even though I believe the writer could’ve written an easier-to-follow story with just the Myra/Robot Harry Potter stuff, that choice would mean less weirdness.

It’s an interesting debate. When trying to create something unique, do you ignore all rules and go on pure gut? Or do you create some boundaries that your story has to stay within? Going back to Being John Malkovich, I can see how logic hounds would’ve ruined that script. “Why do we have to have a 7th and a half floor be the way into John Malkovich’s mind? That doesn’t make sense.” Right, it doesn’t. But it certainly makes the script more charming.

The Boy Who Died has a lot going on in it. And I thought it was a bit over-plotted. But I liked the main character so much that it nudged into “worth the read” territory for me. It’s unlike anything I’ve read off the 2020 Black List and that has to account for something.

[ ] Lord Voldermort

[ ] Draco Malfoy

[x] Butterbeer

[ ] Hermoine Granger

[ ] Harry Potter

What I learned: Over-the-top wild ideas can help you go far in this town. We literally just saw it Monday. Michael Waldron made the Black List with his wacky script, “The Worst Guy of All Time And The Girl Who Came To Kill Him,” a spec that landed him assignments for “Loki” and “Doctor Strange and the Multiverse of Madness.” Wacky crazy ideas indicate someone with a big imagination. And big imaginations are in high demand in an industry where every major franchise is getting wilder and wilder. Go check out the next big Hollywood release – Fast 9 – as a primary example.

It’s taken 45 years to do, but Scriptshadow has finally decoded the secret to Star Wars’s success. And now you can use this secret in your own screenplays!

It’s been a while since I’ve posted about Star Wars, mainly because there hasn’t been a lot of Star Wars to talk about. The Lucasfilm team seems perfectly okay with hiding out on Dagobah for the time being, tired of the Twitterverse questioning every move they make. As they reboot, they’d be wise to read this article, as I believe it holds the key to making Star Wars great again. Or any movie for that matter.

And really, it comes down to one of the most basic concepts in storytelling…

THE ACTIVE CHARACTER

One of the things you hear me talk about all the time on this site is ACTIVE CHARACTERS. An active character is someone who PUSHES FORWARD to achieve a goal. The reason active characters are so important to movies is because when a character is pushing forward THEY ARE TAKING THE PLOT ALONG WITH THEM. You can’t go after Thanos without bringing the entire plot of the movie along for the ride.

That’s why active characters are so valuable. Their actions write the movie for you. The second you switch to reactive or, worse, passive characters, you’ll notice your plot begin to stall. This is why you hear me rail against “waiting around” narratives. If your story is about, say, a couple of friends in a small town who are just trying to survive the boredom of summer, you’re dealing with two passive characters. And since they aren’t going anywhere, neither is your plot.

The use of active characters should extend beyond your hero, though. Ideally, you would like your villain to be active as well. The idea is that on one side you have your hero, who’s actively pursuing his goal. On the other side, you have your villain, who’s actively pursuing his goal. Then you construct the story in such a way that these two goals collide. That’s what causes all the conflict in the movie, is the constant intersection of those goals.

This is why Die Hard remains, to this day, one of the greatest movies ever. On the one hand you have John McClane, who’s trying to save his wife (his active goal). On the other, you have Hans, who’s trying to steal a bunch of money (his active goal). And those two goals collide. John cannot achieve his goal without interrupting Hans’s pursuit. And Hans cannot achieve his goal as long as John keeps getting in the way. Where those goals collide is the playground through which you explore your story.

But you can go one step further! What if it isn’t just your hero who has a goal and your villain who has a goal… but your main supporting character who also has a goal? What if you made him active as well?! This is where you start to see seasoned screenwriters pull away from the amateur crowd. Most amateurs are able to apply everything I’ve talked about so far. However, that’s where they stop. They make sure the hero is after something, the villain is after something, and they’re done.

Working screenwriters understand that the more active characters there are in your movie, the more opportunity there is for ACTIVITY. For PLOT. For CONFLICT. For ENTERTAINMENT. There’s more ON THE LINE. The idea is, the more people you have pushing on your story (active characters create “push”), the more energy your story is going to have.

Which leads us back to the original Star Wars, which I realized the other day may have the most active set of characters in movie history!

Check it out.

To start things off, we have R2-D2. He’s our original ACTIVE HERO in Star Wars. He has the Death Star plans that he must deliver to Alderran. R2-D2 is determined to secure an escape pod and shoot down to the planet of Tatooine NOW.

Following immediately behind R2-D2 is Darth Vader, our villain, and arguably the character in Star Wars with the strongest goal. He has to retrieve those Death Star plans before they make it into the hands of the Rebellion or else the Empire is doomed.

Our next active character is Obi-Wan. When he receives Princess Leia’s message, he becomes the primary active character in the script. He must deliver R2-D2’s Death Star plans to Alderaan. So now he’s squarely on the active train.

Of course, not far behind is Luke. Remember, Luke isn’t active at first. He’s stuck on the farm, unable to leave. But when his aunt and uncle are killed, Luke is all about helping Obi-Wan. From that point on, he becomes an extremely active character.

Next up we have Han Solo. Han could’ve easily been constructed as a passive pilot – a character merely meant to transfer Obi-Wan and Luke from Point A to Point B. But what fun would that be? Instead, Lucas gives Han his own goal. He owes Jabba the Hut a ton of money. Obi-Wan is giving him some of the money now and the rest after they achieve their mission. So it is extremely important that Han succeed. Now HE’S a super-active character.

Finally, you have Princess Leia. Princess Leia was technically an active character before anyone, since she’s the one who initiated the mission to get the Death Star plans to Alderaan, inserting them into R2-D2. But because she’s captured early by Vader, she doesn’t get a chance to display her activeness. However, the second they rescue Leia, she arguably becomes the most active character in the group, blasting open walls to create escape opportunities and making sure they get to the Rebel base in one piece.

Every single main character in Star Wars is EXTREMELY active.

I don’t think that’s an accident. I think it’s a major contributor to why the movie is one of the best of all time. Again, whenever you make a character active, you are inserting a unit of ‘forward-moving energy’ into the story. The very nature of activity is that you are attempting to push something along. So it makes sense that with every additional active character, you are adding more energy to the mix. At a certain point, if that many characters want something, your movie is this giant blinding force of energy that can’t be stopped.

Now it’s important to remember that not all activity is created equal. Someone can be active by painting their house in hopes that it will look nice when the in-laws visit for the weekend. Someone else can be active by hunting down the man that kidnapped their daughter. No matter what you do, Active Kidnapper Hunter is always going to inject more energy into the script than Active Painter Husband.

The more intense the activity, the more energy there is in the story. That’s where Star Wars separates itself from other movies. Not only are there so many active characters, but all of them want their goal so badly that they’re bringing an insane amount of energy to the picture.

Something to keep in mind here is that Star Wars is a variation of The Hero’s Journey. The Hero’s Journey is just like it sounds. It’s a character going off on a journey. I bring this up because it’s always easier to make characters active when they’re on a journey. That’s because it’s hard to physically move from Point A to Point B of a journey without some level of activity.

In other words, Star Wars has an advantage. Its story is built around an “active-friendly” premise. It encourages active characters. You might not have that opportunity if you’re writing a contained thriller. But that doesn’t mean you shouldn’t try to write active characters. In fact, I would always start out with any character you create, trying to make them active. I don’t care if it’s the hero or the 8th most important character in your script. Active characters create plot opportunities. Passive characters wipe story out. It’s hard to come up with plot ideas if your characters aren’t leading the charge.

And just to be clear, I understand that every movie is different. Empire Strikes Back’s first 20 minutes is technically a “waiting around movie.” But the reason it works is because at least one major character, Darth Vader, is actively pursuing something. He’s trying to find the secret rebel base which he will then attack. So even if you can’t create a plot where everyone is active all the time like Star Wars, make sure that as many of the major characters are actively pursuing something as you can. That’s why, instead of completely waiting around in the first act of Empire Strikes Back, they had Luke get attacked by the Wampa. That gave Han a goal (find Luke) which allowed him to be ACTIVE.

I’ll finish up by asking the question again. Is it any coincidence that the greatest movie of all time has six of the most active characters of all time in it? I don’t think so.

Carson does full screenplay consultations as well as consultations for pilots, loglines, outlines, treatments, whatever you’ve got! If you’re interested in getting a consultation, e-mail carsonreeves1@gmail.com with the subject line “Consultation.” Looking forward to working with you!

Genre: Drama/Thriller

Premise: A patriotic pipeliner from the heartland of America must go to France to prove his daughter’s innocence, as she’s in prison for the murder of her Arab lover.

About: You may have heard me talking about this one in the newsletter. It’s directed by Tom McCarthy (Spotlight) and stars Matt Damon. The movie is coming out in July.

Writers: Thomas Bidegain | Noé Debré | Marcus Hinchey (screenplay) and Tom McCarthy

Details: 122 pages

One of the obstacles you’re faced with when writing an “adult” movie is deciding how much of the Hollywood formula you want to ditch and how much you want to keep. Traditional story mechanics (a beginning, middle, end, GSU, conflict, drama, etc.) will work across all demographics.

But there is something to be said about muting commonly used components to make adult stories feel more realistic. It’s always a question of how much muting do you want to do. Because, at a certain point, you start eating into the drama. You start eating into the conflict. That’s the dilemma that today’s script faces. In its pursuit of realism, it dances with some decidedly non-dramatic choices. Let’s see how it turned out.

50 year old Bill Sedowski is a pipeliner. He’s the guy who digs into the earth and literally lays oil pipe, as American a job as someone can have. And that’s appropriate for Bill because he’s a hardcore American, the kind of guy who prays before every meal and doesn’t buy a cap unless it has the American flag on it.

So we see the fish-out-of-water contrast right away when Bill lands in Marseilles, France. It takes us a few scenes to realize why he’s here but we eventually learn his daughter, Allison, has been in prison for five years for the murder of her lover, an Arab girl named Lina. Bill heads over to the prison to see his daughter, something we realize he’s done dozens of times before. But this time she gives him a letter and says to please hand it directly to her lawyer, who isn’t talking to Allison anymore.

Bill does as told, trapping the squirrelly lawyer at the courthouse, who reads the letter (it’s in French) and tells Bill that she can’t help and that Allison needs to accept what she’s done. Nice lawyer! When Bill gets back to the hotel, he runs into a kind young woman named Virginie, who’s staying next to him, and he asks her to translate the letter for him.

It turns out that someone overheard some kids talking at a party and a dude named Mika was bragging that he killed Lina. Allison was hoping her lawyer could match his DNA against the crime scene. When Bill visits his daughter the next day, she asks, hopefully, if her lawyer accepted. Seeing the desperation in her eyes, Bill chooses to tell his daughter that the lawyer did accept. She’s going to look into it.

That now means, of course, that Bill will have to look into it. It’ll be up to him to find this Mika character. No small task considering he doesn’t even speak the language of the country. Bill finds some help in the girl who translated the letter for him, Virginie. She becomes his translator on this mission and off they go, determined to prove Allison’s innocence.

Let’s talk about some of these unconventional choices I alluded to in the introduction.

The first is coming into the story very late. In a traditional Hollywood movie, we’d show the events that led to the murder or wake up the night after the murder. From there, we’d watch the whirlwind unfold, requiring the father to fly from America and try to save his daughter.

But Stillwater starts a good FIVE YEARS into the process. That’s how long Allison has been in prison already.

I’m not sure how I feel about this. With movies, you’re always looking for situations that create a natural ticking time bomb, or at least some level of urgency. If you start the movie the day after the murder, for example, there’s a ticking time bomb in that the media and police are looking to charge Allison. That gives you a limited amount of time to prove her innocence.

By coming into the story so late, there is no urgency. She’s already in prison. Anything Bill doesn’t achieve now, he can try again in a week, a month, six months. That’s not ideal in storytelling. You want there to be an “all or nothing” component to achieving the goal. If Hero doesn’t achieve X by Y amount of time, he never gets another shot.

When movies move away from this, it’s usually because they want to “de-Hollywoodize” the storytelling so it feels more authentic. Seeing as Tom McCarthy threw all drama out the window to make Spotlight as realistic as possible, I’m not surprised he’s doing the same thing here.

The surprising thing is that, for the most part, it works. The reason for that is the characters. One of the best ways to deepen a story is to explore a broken relationship, usually within a family. But you can’t cheat. It can’t be bargain basement Tuesday backstory “Daddy didn’t hug me” stuff. It’s got to have some depth to it and some specificity, so it feels like there’s a real past here. And you need a little luck. You can do all this stuff right and for whatever reason it doesn’t work.

The part that hooked me in this relationship was when Bill was having Virginie translate the letter his daughter wrote (the letter is in French). Here is the last paragraph: “I am innocent of this crime and I have no one else to advocate for me in this situation. My mother is dead. My Grandmother can no longer make the trips to Marseille and you know my father. I would not trust him with this. He is not capable. You are my only hope.”

I mean how much more heartbreaking can you get than a daughter who doesn’t believe her father is capable of helping her? And that’s what sets up the compelling goal of the story, which is Bill trying to do the very thing that his daughter doesn’t think he can. But it isn’t just that. Bill’s not trying to prove his daughter wrong. He wants to save her. In the process, if he can, he’ll also get his daughter to believe in him again.

That’s why I wanted to stick around for this ride. I wanted to see if Bill could both save and win his daughter back. That’s when a screenplay really works, is when the reader is more invested in the character side of the goal than the plot side of the goal. In other words, you could’ve written this exact same movie but with a blander family backstory and still had that satisfying moment when the father proves his daughter’s innocence. But it works so much better when we feel the emotion of that actually mattering for the future of these characters.

In classic McCarthy fashion, he plays with storytelling fire, at one point jumping forward in the story FOUR MONTHS. When you do this, you erase all tension that you’ve built up so I highly advise against it. But the story is saved, once again, when the murder mystery returns to the script’s pole position and we learn what really happened that night. It’s quite the ending.

I don’t know if anyone under the age of 40 is going to like this movie. But the people who love to show up for those Clint Eastwood matinees are going to love it. :)

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[xx] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: This is a clever way of exploiting a well-known murder story, as this is obviously based on the Amanda Knox case. You can do this to come up with some good ideas of your own. You simply take an interesting real-life murder case (or any popular story in the news) and look for an emotional component to it and tell the story from that angle. You could have told the Amanda Knox story a number of ways. You could have told it through the point of view of Amanda. You could’ve told it through the point of view of the lawyer trying to get her off. You could’ve told the story in third person and cut back and forth between all of the main players. Today’s writers took the route of exploring what it would’ve been like to be the father of a girl accused of murder in another country. That’s what allows them to get away with, basically, stealing a well-known murder story.