Hey guys. I know you’re all eager to find out who won the screenwriting contest. And I’m just as eager to tell you! Unfortunately, this is the first time I’m coordinating an announcement with several different parties (writers, production company, trade websites). And we’re still ironing out some last second things. Hopefully, I’ll be able to post the winners at some point today. So stay tuned. Since you probably don’t want to refresh until your fingers fall off, you can follow me on Twitter, where I’ll announce that the post is up. Sorry for the delay!

Genre: Drama/Thriller

Premise: When a young woman is found dead in rural Wyoming, a wildlife serviceman who usually tracks mountain lions must team up with a young FBI agent to track a killer.

About: This is the new script from Sicario screenwriter, Taylor Sheridan, who will be making his directing debut with this, his third script. Avengers alums Jeremy Renner and Elizabeth Olsen play the leads. The project just finished shooting and is putting together an assembly cut.

Writer: Taylor Sheridan

Details: 112 pages

Someone made a point about Taylor Sheridan’s scripts when we were choosing loglines for the Scriptshadow 3 Month Script Challenge. The crux of his argument was: You’re forcing us to come up with these perfect loglines yet guys like Taylor Sheridan are breaking through with Sicario, a logline that doesn’t even sniff okaytion.

Point taken. So let’s figure out why Sheridan’s script still broke through. Ideally, as an unknown, you want an idea/logline that stands out. It’s the best way to get noticed. I will continue to shout to the rooftops that the way through Hollywood’s golden gates is a kickass logline.

Your next best shot is to write something with a unique voice, try to make the Black List, and sneak in through the back door. And that’s how Sheridan did it. His scripts are built on a unique voice, which I’ll touch on more after the summary.

But first, remember that these areas are not mutually exclusive. The ideal situation is that you come up with a great concept AND write with a unique voice. But absent one, make sure you have the other. Okay, now, what’s this “Wind River” about?

Cory Lambert is an agent for the United States Fish and Wildlife Service. If you’re anything like me, you didn’t know that existed. But up here in Wyoming, where the wildlife and the human life intermingle more than in your typical state, people like Cory make sure that the animals don’t cause too much trouble for their bipedal neighbors.

When Cory gets a call that an overzealous mountain lion is wreaking havoc in the northern woods, he goes to check it out, only to find a dead 18 year old girl instead. Both the local sheriff, a Native American man, and Jane Banner, a fresh off the assembly line FBI agent, come in to investigate.

What’s strange about this death is that snow tracks indicate the dead girl was running alone for miles. She should’ve died from weather exposure way sooner. And what exactly was she running from?

They first check out her boyfriend, a meth-addict, and it looks like this’ll be solved quickly. But it’s not clear that the boyfriend or his fucked up buddies have anything to do with this. As Cory and Jane begin to connect the dots, and find another dead man soon after, they realize that there may be a lot more going on here.

Complicating matters is that Cory lost his daughter at about the same age under similar circumstances. Could these deaths be related? And the big-city Jane isn’t helping things by purporting to know it all, despite being the least equipped to navigate the strange American/Indian inter-dynamics that go on in Wyoming. When all is said and done, the reluctant partners may be lucky if they don’t kill each other first.

As promised, I want to talk about “voice,” that elusive quality you keep hearing about on screenwriting sites, that is essential to screenwriting breakoutability, and how it applies to Wind River (and Sheridan’s scripts in particular).

The main component associated with voice is a unique sense of humor. Guys like Charlie Kaufman or Wes Anderson come to mind. The next biggest is point-of-view, or “how one sees the world.” Quentin Tarantino, for example, sees everything through the glasses of a 1970s Western with an Ennio Morricone soundtrack playing in the background.

But the way Sheridan displays voice is a little different. His voice is conveyed via a world that he knows about but we don’t. In this case, northern Wyoming, Indian Country, the kind of place where an aggressive mountain lion is more important than whether Kylie Jenner is still dating Tyga.

Because when you break “voice” down, it’s basically about being unique. Any way you can achieve uniqueness, the overall “voice” is going to sound different, and that’s exactly what Sheridan does.

This is why I keep reminding you guys, if you grew up somewhere other than New York, Los Angeles, or Paris, take advantage of that in your writing! The things that may seem common/mundane to you may very well be unknown/fascinating to us. If you can build a story around that, you have the potential to write something memorable.

Now there is some strategy to it. If you live out on a farm in the middle of nowhere and you want to write about the trials and tribulations of farming, readers probably won’t stick around. But if you write about a string of murders on a farm that takes place during a two year drought, you may have something.

So how did this factor into Wind River? Was it any good?

I’ll start by saying this. Sheridan is REALLY GOOD with character. When you read his stuff, the people feel real. That’s such an underrated skill. The large majority of characters in scripts feel written. Sheridan’s mastered the art of simple interactions that say a lot (a look between a man and woman who used to be married, for example). It’s rare that characters feel so consistently genuine.

Here’s where things got tricky though. In each of Sheridan’s scripts, they always start strong, then somewhere around the midpoint, they lose steam or lose focus or lose something. It’s hard to define. But I’ll notice around page 65 that I’m not as invested as I was 20 pages ago. And I don’t know why.

One of the things I’ve noticed with these dramatic (and therefore slower) thrillers is that they can get away from you if you’re not careful. If you don’t stay on the plot and keep things interesting, they can get boring FAST. I almost feel like they need more jolts, more twists or turns to keep us on our toes. Because what you don’t want is it to turn into a straightforward been-there-done-that investigation flick. SO MANY of these slow thrillers end up there. And Wind River did start to feel that way (at least for awhile).

With that said, there’s still a lot to like. One of my favorite moments was the introduction of Jane. We’d been watching Cory navigate the land by deer poop and tree branches, and then Jane pulls up in her SUV, and her GPS is telling her to take a right, but there is no right because the road has been covered up by snow, so she literally has no idea what to do. If the GPS can’t tell her where to go, she doesn’t know where to go.

I LOVE when writers do a good job setting up the contrast between major characters and most of that is done through introductions. I just found this to be the perfect way to show that this woman lived in a completely different world than these men.

Another thing I like about Sheridan is how SPECIFIC he gets. This is a big way to set your script apart. So, for instance, when Cory explains to Jane the difficulties in gauging how long someone can last out in the cold, he delivers this line:

I seen tourists freeze to death in these mountains when it was barely 40 degrees … I seen a fur trader caught in his own trap, drag himself six miles to a forest service cabin and radio for help. In the dead of winter … There ain’t no gauge for the will to live. Some have it. Plenty don’t.

I mean who thinks up a fur trader getting trapped in his own trap and then draggig himself six miles other than someone who lives in this world? This may seem like a small thing but it’s specificity like this that separates your script from all the generic garbage that’s written every day. I’ve read hundreds of similar scripts and the majority of the time, I’ll get a line closer to this:

I’ve seen people make it 10 miles in a t-shirt and 2 miles in full-on ski gear. It’s all about the will to live.

That line indicates a writer who knows ZIP about northern Wyoming in the middle of January.

All in all, Wind River is good. It slogs some in its second act. But the setup is great, the setting is unique, the characters feel honest and are easy to root for, and the overall voice is stellar. If you’re afraid of the high-concept world and want to break in on voice alone, Sheridan’s scripts are good scripts to study.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: A storm coming in is an easy way to bring excitement to a slower story. Remember that you’re competing with 300 million dollar comic book films where every frame is designed to blow your brain up. You want to look for any trick you can to add excitement to your much smaller story. The indication that a storm is coming adds TENSION, SUSPENSE, and A TICKING TIME BOMB, all things that beef a story up. Fight capes with good storytelling, guys. :)

Note: I screwed up with the Scriptshadow 250 Top 5 Announcement. Monday, as we Americans know, is a major holiday (Memorial Day). So we’re going to move that announcement to Wednesday instead. Sorry about that!

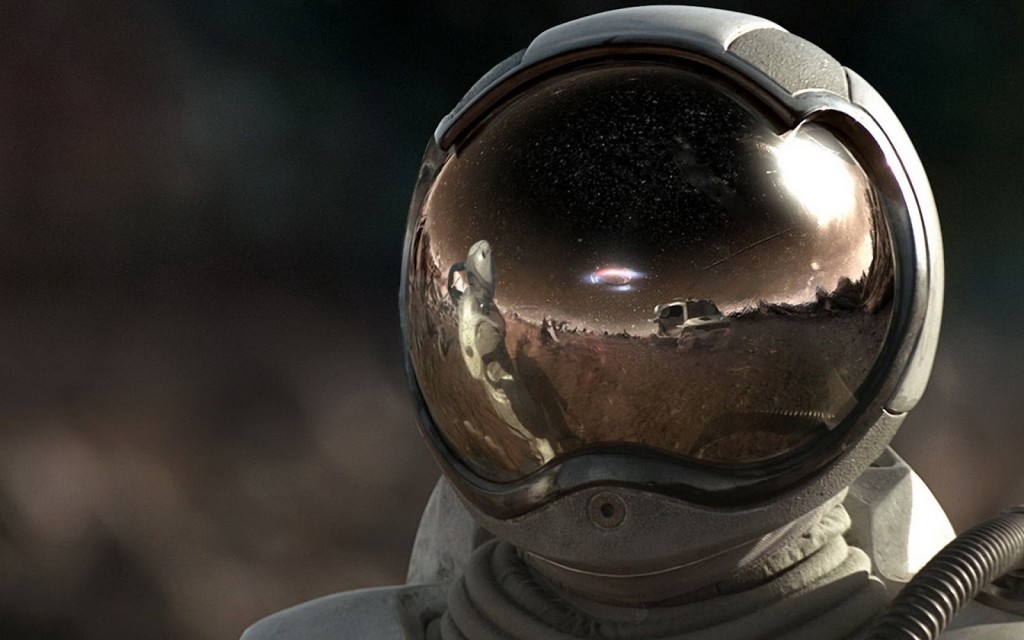

Genre: Somnium

Logline (from writer): A loyal astronaut, scheduled to be on the first mission to Mars, begins having terrifying dreams of the mission going wrong. Then, when the mission is sabotaged, he finds himself the prime suspect.

Why You Should Read (from writer): I’ve been writing for three years now, my script Jack Curious is in the Scriptshadow top 25 at the moment. This script is the script I wrote to teach myself the craft, and while it made the quarterfinals of the Big Break Contest and connected me with some cool people, it’s been sitting on the shelf for the last two years. I’d love the opportunity, with the help of the SS community, to pull it apart and work out how to make it better. I also have most of the budget together to make my narrative feature directing debut (I’ve only done docos so far), and I’m wondering if this could be the script to do it with.

Writer: Bryce McLellan

Details: 109 pages

We’re seeing a lot of Mars projects these days. We had The Martian. There’s that new weird Mars teenage love story (that I reviewed a few years back and was convinced would never see the light of day). There’s a Zachary Quinto movie I just learned about called Passage to Mars that for some reason takes place in Antarctica. There’s the Deadpool writers next sorta-Mars movie called “Life.” There’s “Approach The Unknown,” about a single manned Mars Mission. There’s one of my favorite amateur scripts submitted to the site, The Only Lemon Tree on Mars. And if you want to get really technical, they’re thinking about making a sequel to Veronica Mars.

What does this mean?

Hell if I know.

People have a galactic hard-on for red dirt?

I guess if we want to get into it, there’s something to be said for understanding where the hot topics are. Because once you know you’re playing in the same sandbox as everyone else, you have to decide if you can build a better sandcastle than them. If all you’re going to do is fill up your Big Gulp cup with goopy sand and flip it around four times and call it a day, your sandcastle probably won’t be able to compete with the next guy’s.

That’s why I recommend staying away from the hot subject matter. If everyone’s writing about Mars, write about Neptune. Or Uranus. Heh heh. Heh heh. “Uranus.” However, since we can’t go back in time and warn Bryce about this, we’ll have to see if he’s pulled off Plan B: finding a new angle into a Mars story.

The year is 2050 or so. Sam obtained the Mars Mission astronaut job when one of the other astronauts went crazy. I guess being picked for the first mission to Mars can be a bit anxiety-inducing for some. Joining Sam will be the Buzz Aldrin-like Jack and the smart-as-a-whip, Connie.

The American-led launch is competing against a similarly constructed Chinese launch, and just like when two Hollywood studios get the same idea at the same time, instead of joining forces and creating the best launch possible, they waste a lot of money to win the race by a few weeks!

And then Sam starts experiencing nightmares. They’re flying to Mars, their ship disintegrates, he lands on the surface with a thud. And then there are the winds. Sam can’t stop having nightmares about those horrifying 200 mile an hour Mars windstorms.

Meanwhile, as we move closer to launch, we cut back in time six months, where we learn that Sam’s wife, Kate, was pregnant. Since she’s not pregnant in the present, and we don’t see any kids around, we get the sense that that situation didn’t end well. And subsequent flashbacks will confirm that.

When a fire on the shuttle sets the launch date back a few months, people within this NASA-like operation begin to suspect that someone’s working for the Chinese, possibly sabotaging the mission so that China can launch first.

The big question is: Is it Sam? A lot of people think so. And with Sam’s nightmares getting worse, with his brain starting to break down, not even he’s sure anymore.

Let’s start with the good news. This is NOT like other sandcastles. And I should’ve known that since Jack Curious, Bryce’s Top 25 Scriptshadow 250 script, is anything but normal.

However, I think Somnium suffers from the flip side of things. Have we deconstructed storytelling TOO MUCH here? Is this “too indie?” Is “too indie” even a thing? I think so. But I know a lot of you don’t.

Let’s start with the flashbacks. Whenever I look at flashbacks, I ask the question, “Are they necessary?” 99% of the time, they’re not. But when they are, they’re usually used in a pattern. And that’s because the writer is using them to tell a separate story in the past, that, if told well, can actually be as interesting as the present story.

I’m not sure this flashback story passed that test. It’s about a woman losing her child. And the thing was, we already knew she lost the child. Like I pointed out, we didn’t see any kid in the present. And she wasn’t pregnant in the present. So obviously she had to have lost the baby.

So why is it important that I see that for myself? Why can’t that just be backstory and not a series of flashbacks? I don’t have a good answer for that, and therefore I’d argue the flashbacks weren’t necessary.

Next up is the way the plot was designed. And Bryce takes a HUGE chance here. I give him credit for that. But let’s look at this logically…

Remember the movie, National Lampoon’s Vacation? The original one with Chevy Chase? Remember what they were trying to do? Get to Wally World, right? Well imagine if that movie wasn’t about actually going to Wally World, but rather about getting in the car that would take them to Wally World.

That’s kind of what this felt like to me. And I’m not saying that the destination has to always be the biggest thing possible. But when you dangle something as exciting as Mars in front of the viewer, and then you tell them we’re not even going to see Mars in the movie…it’s kind of like a literary version of blueballs. We feel cheated, right?

Now, to Bryce’s credit, Somnium starts to get a lot better in its second half. The main reason for that is the China mystery. Are they sabotaging the launch? And if they are, is Sam involved? That was the plot point that drew me back into the story after I got pissed when I realized we wouldn’t be going to Mars.

I also liked the mystery of Sam getting fed these suspicious pills. It added another layer to the sabotage mystery. Maybe someone was manipulating Sam to sabotage the launch without his knowledge?

Unfortunately, none of this stuff gets paid off in a satisfying way. It was paid off in that vague “you decide” way. And I’ve never been a fan of that.

If I were Bryce, I would introduce the Chinese sabotage mystery much earlier in the script. Make it a major plot point. Because if there’s one thing this script lacks, it’s structure. It’s plot. It’s built on this wishy-washy foundation of flashbacks and character uncertainty. It needs a plot that’s more definable.

Then use the flashbacks as a decoy. We think they’re about Kate losing the baby. But through them, we reveal that Sam IS actually involved with the Chinese, therefore making the past plot an official part of the story as opposed to just character backstory.

The more you structure Somnium, the better it’s going to be. And I think Bryce is a good writer. So he can pull it off. But it’s going to require work.

Script link: Somnium

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Flashbacks JUST FOR CHARACTER BACKSTORY are usually a bad idea. If you’re going to use flashbacks, use them to ADD TO THE PLOT. We should learn cool things in the flashback that we couldn’t have learned in the present. And these things need to AFFECT THE PLOT. That’s one of the only times flashbacks can be an asset.

Okay guys. So last week, we got up to page 40. At least I hope we did. Since this is screenwriting, I’m sure a spoon full of you made up reasons to watch 15 movies in the genre you’re writing as part of your “research,” cough cough.

Look, I’m not going to pretend like that’s never happened to me. Sometimes we are faced with the inability to come up with creative ideas and when that happens we’ll look for anything to do other than write. But if you’re going to get this script done on time, you need to throw away that judgement voice in your head and get those pages down.

Ultimately, you want to work in this business, right? Well guess what happens when you have an assignment due? Do you think the people paying you 500k are going to be like, “Oh yeah, just get it to me whenever inspiration strikes.” Yeah, unless you love giving studios reasons to void a contract, I’d suggest getting used to deadlines. Consider this practice for the big leagues.

We are now inside those 50 or so pages that many refer to as “the jungle,” because it’s where screenplays wander into and never come back out. Luckily, we outlined ahead of time, we did character work ahead of time, which means this section should be easier for you than for the guy who thought he’d write a script and “see where it goes.”

This week, we’re writing to the midpoint, which should be somewhere between pages 55 and 60. The midpoint is where you’ll be throwing a game-changer of a moment into your story. Maybe it’s plot related. Maybe it’s character related. It could be a major reveal, a major reversal. But that’s not what we’re going to be talking about today. Because we still have to write 5-8 scenes JUST TO GET US TO THAT POINT.

In order to understand what those scenes should be, we need to remind ourselves what the second act is and why it’s so difficult. The reason the second act is so tricky is because it’s the least definable section of the story. The first act is obvious in its intent. It’s SETTING THINGS UP. The third act is obvious in its intent. It’s CONCLUDING THINGS. That gives both acts AN IDENTITY.

Think about that for a second. Because it’s the MAIN REASON why the second act is such a fluckstercuck. Screenwriters literally have no idea what the intent of the act is. And what happens when you write without intent? Your story goes fucking nowhere, that’s what happens. So for us to even approach a strong second act, we have to define the act’s intent.

The second act’s intent is: CONFLICT

If you remember that the goal of this act is to create and sustain conflict, you should be all right.

Now, there are three areas of conflict you’ll be exploring…

Plot obstacles.

Conflict between your hero and others.

Conflict within your hero.

Let’s start with plot obstacles because it’s the easiest one. But you have to understand something first. If you haven’t set up a goal for your hero to achieve, you cannot place obstacles in front of anything. This is why goal-less character scripts are usually so boring. By the very nature of not having an objective, you can’t place anything (obstacles) in the way of that objective. That’s why I go on and on so much about goals. Because it’s hard to make a plot interesting if you don’t have anything to disrupt it.

Can it be done? Yes. But only if you are a MASTER at character development and character conflict. Which means you have to get these next two things right.

Conflict between your hero and others is the process of coming up with an “issue” between two characters and having those characters butt heads over that issue throughout the script. Take Lester Burnham in American Beauty. The very first element of conflict brought up in that movie is that Lester’s wife, Carolyn, has tuned the fuck out of the relationship. She doesn’t respect him anymore. So every time we see those two together, we can explore that lack of respect. That’s the IDENTITY of their conflict.

Where conflict between your hero and others gets tricky is in the variety that’s required. You need to come up with different types of conflict between different characters. So to use American Beauty as an example again, Lester’s daughter, Jane, and him just aren’t friends anymore. They don’t talk to each other. The IDENTITY of that conflict is different from one person not respecting another person.

The point is, a large portion of the second act will be used to explore conflict between characters. This will be less so in action and thriller scripts and more so in character pieces and dramas. But it will be there in some form or another in EVERY SCRIPT.

This brings us to our last form of conflict – conflict WITHIN the hero. This is the hardest form of conflict to execute because it’s difficult to take something internal and explore it externally. That’s why I always encourage writers to consider this when coming up with their hero’s flaw. There are certain internal flaws that are easier to explore externally than others.

Selfishness is one of them, obviously. It’s easy to come up with scenes where your hero picks himself over others. Lack of belief in one’s self is another. Being stubborn. Not living in the moment. Puts work over family.

These are all (more or less) internal flaws that can be explored externally. You achieve this by putting your character into repeated situations that directly challenge this flaw. So if you have a character who’s stubborn, like, say, Gene Hackman as the coach in the basketball movie, Hoosiers, you show him at his first practice with a group of townspeople who show up and say that they believe the practice should be run THEIR way. This is a direct assault on our main character’s flaw. Which means we not only get to explore his flaw, but we get to infuse a scene with CONFLICT. And as you now know, that’s the name of the game in the second act.

If you want to get into some advanced shit, make sure you’re sitting. Because things are about to get all AP English up in this mug. If you want to explore character and conflict in a truly impactful way, each subsequent “attack” on your hero’s flaw should be more credible than the last. So in the scene above, of course Gene Hackman’s going to tell a bunch of a-holes to screw off when they invade his practice. But later on, when the woman Hackman is falling for, a teacher, starts telling him that it’s more important for these kids to get an education than spend every waking moment practicing basketball, now his stubbornness is really getting tested. Because there’s more at stake by telling this person no.

Finally, the second act is a big place. So while I’m promoting a structural approach to it, I still want you to be creative. Follow your imagination. Try things out. You can always pull it back in if it gets too crazy. But I don’t want your script to feel like ScriptBot4000. It still needs a heart. It still needs to breathe. So make sure you’re still having fun.

Good luck, guys. You’re almost halfway home!

Genre: Action

Premise: When Air Force One is shot down in South America by terrorists, the female president of the United States must be rescued by a local Seal Team that isn’t too fond of her.

About: This script sold last year to Millennium Films and was written by Gregory Allen Howard, who wrote Remember The Titans as well as did some work on “Ali.” Howard is trying to move away from more serious stuff and re-brand himself as an action writer. Looks like it’s working out so far!

Writer: Gregory Allen Howard

Details: 122 pages – 1st draft

Hollywood. Loves. Action.

They love it.

It is the genre that will never die because it PLAYS EVERYWHERE. And in an ever-expanding global market, it gives studios the best chance for a big return on their investment.

Strangely, many of these action specs that get purchased never get made unless they stay closer to the action-thriller genre, which is a little more focused, less grandiose – stuff like Taken. These big idea action specs are having trouble getting green lights, and I have some theories on why which I’ll share in a moment. First, let’s check out the plot here.

Karen Morgan is the tough-as-nails president of the United States. When she learns that Hakim Ibn Al-Libi, a top Al-Queda terrorist, is in Somalia, she orders a local American military outfit to grab him. Led by tougher-than-nails Commander Bobby Lee, the Americans Zero Dark 31 him up.

Unfortunately, they find out that the President has decided to swap Hakim back for one of their own. Lee is pissed, but since those decisions are way above his pay grade, he rolls with it. That is until a week later when Lee’s son is killed in a suicide bombing… by Hakim!

Meanwhile, President Morgan is heading down to Ecuador for some conference, but as soon as they land, they’re attacked by the local military… who just so happens to be led… by Hakim! Air Force One is able to take off, but is shot down immediately. President Morgan is able to eject via the special Air Force One “escape pod,” but now finds herself in the dangerous jungles of nearby Columbia, with a quickly approaching Hakim.

Back in the U.S., they learn that the closest team to extract the president is… Bobby Lee’s team! And therein lies the irony. The guy whose son was killed because of a direct order by the president is now tasked with saving the president!

The rest of the script plays out like a game of cat and mouse, with some really big cats and some really gnarly mice. In classic early 90s action form, we have our control room, our president and her Seal Team, the pursuing baddies, and the nearby extraction ship. Will our female prez make it to safety? That will be up to a still simmering Bobby Lee, who doesn’t take too kindly to presidents killing his son.

Okay, before we get into my thoughts on action specs, I first have to regurgitate a rant.

I hate reading these presidential scripts.

There are at least 25 characters (joints of chiefs of staff, CIA directors of staff, Defense Secretary of Staff) you have to keep track of, and you have no idea which ones are One-Scene Johnnies and which ones are sticking around for the long haul, which means you’re spending all this mental energy on remembering people who don’t matter.

The worst are these 3-characters-introduced-in-a-single-paragraph moments. You might as well hold a screenwriting funeral for those characters because there’s no way in hell the reader is going to remember them. All of this gives the script more of a homework assignment feel as opposed to an entertaining piece of fiction.

To some degree, I understand that this is necessary. To feel authentic, you need a lot of the periphery government people around the president. But as a writer, it’s your job to be aware of that problem so you can curb it whenever possible. For example, if there are any single-scene characters, do you really need to give them a name? A reader’s brain only has so much space to fill up. You don’t want to gum it up with unimportant people or information.

Story first story first story first.

The priority is always writing the most entertaining story. You then go back and include the minimum plot, logistics, and exposition you can get away with. Cause nobody gives a shit about any of that if they’re not entertained.

Now this next issue may be because this is an early draft, so keep that in mind, but I don’t like my action scripts to have a ton of 3-4 line paragraphs like Hunt Capture Kill did. I like things to be a little more cut-up, spaced out. Remember that how something is read has to feel like how it will be watched. Action moves faster than any other genre with the exception of maybe comedy. So the paragraph structure should reflect that. Keep things closer to 2 lines each, with a 3-liner every so often.

Now onto these modern-day action specs and where they go wrong.

I believe that too many action writers are attempting to resurrect the 80s action film. The thing is, that era is dead. That was a time when the your main character could pump out jokey one-liners every time he killed a man. For whatever reason, today’s audiences require a more believable vibe.

True, everything is cyclical, but just like fashion, you can’t bring it back in the exact same form. You have to find a way to modernize it. And these big concept 80s type specs feel more trapped in the past than they do reinvigorating it.

A successful example is Fast and Furious. We didn’t have any major drag-racing action movies back in the 80s. So that movie felt unique when it came out. And I happen to know that when producers talk about looking for scripts, “something like Fast and Furious” comes up a lot, because it’s a franchise starting film that doesn’t cost the studio an arm and leg to buy up any IP. It really is an ideal space for a spec screenwriter to write in.

With that said, I was open to hunting, capturing, and killing here. And one of my criteria for good action specs is: Do I see anything in the first act that I haven’t seen before in an action movie? Genre movies are easy to write if all you’re doing is rewriting your favorite scenes from previous genre movies. They’re a lot harder to write if you’re trying to be different. So I know if I see something different, I’m in good hands.

The setup here was very standard early 90s stuff. Get the terrorists, meet the government, set up meeting in Ecuador, plane goes down, team goes in. Where was a scene I hadn’t seen before?? The first time that happened was halfway into the script when our SEAL team comes across two hot bikini-clad Columbian women bathing in an isolated river who then take out some AK-47s and start shooting at them. However, I’m still not sure how that scene made sense. Does Al-Queda employ beautiful half-naked women in isolated parts of the jungle? Or were these two just really pissed off that someone was interrupting their daily swim?

I did like that the person charged with saving the president was someone who hated her. But the more I thought about this idea, the more I wondered if it would be better if the president was male and the person charged with saving him was a woman. Wouldn’t that be a more original (and interesting) take on this setup?

I don’t know. As I said already, this is a first draft. So maybe a lot of this gets sorted out later. But I was definitely hoping for more.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: One-Scene Johnnies. Characters who are only in the script for one scene. Think long and hard before you name these characters. If you really truly think they only work with a name, name them. Otherwise, call them by something general (Waitress, Lieutenant) so as not to force the reader to remember someone meaningless.

What I learned 2: Whatever genre you’re writing in, make sure at least ONE of the scenes in your first act is something we haven’t seen before in that genre. If you can’t be original in your first act, why would I believe you could be original for the rest of the script? And really, you should be doing this with more than one scene. One scene is the absolute minimum.