Genre: Drama/Mystery

Premise: After a home invasion ends in the accidental murder of a mother, her young son is convinced that he knows who the killers are. Unfortunately, nobody believes him.

About: This is a script that the Coen Brothers wrote back in 2007, but it never made it into their production pile. Enter George Clooney, who ADORES the Coens. If they’ve got an available script floating around, you can bet your ass he’s going to read it. And apparently, he liked what he saw. Also, cause he’s George Clooney, he can get a killer cast. Suburbicon will star Oscar Isaac, Matt Damon, Julianne Moore, Josh Brolin, and Woody Harrelson.

Writers: Ethan and Joel Coen

Details: 113 page – March 27, 2007 draft

As some of you know, I have a love-hate relationship with the Coen Brothers. At times I believe they understand screenwriting better than any writers in Hollywood. They’re great at stripping plots down (usually focusing on a bag of money), populating their stories with unforgettable characters, and making unique choices.

But then they make movies like Inside Llewyn Davis, which seemed to breed boringness, or Hail, Caeser, which seemed so desperate to make up for that boringness, that it became boring in its anti-boringness. In many ways, the Coens are a victim of their unique voice. By the very nature of being so different, audiences aren’t always going to come along for the ride with you.

This time, the Coens are handing over directing duties to their star pupil, George Clooney. Clooney, who’s directed four movies so far, seems to want to take the Clint Eastwood approach to his career. He’s repeatedly said he’s uncomfortable with getting old onscreen, so I imagine we’ll soon see him exclusively behind the camera. Let’s check out what he’s working with this time around.

8 year-old Nicky Lodge hears his dad outside his bedroom door talking to an unfamiliar voice. When his father, Gardner, opens the door, he tells Nicky that a couple of men are here, and as long as we do what they say, they’ll leave us alone and everything will be all right.

So Nicky, Gardner, Gardner’s wheelchair-bound wife, Rose, and Rose’s sister (Nicky’s aunt), Margaret, are taken to the basement, tied up, and given chloroform. When Nicky wakes up, he’s at the hospital learning that his mother is dead.

Later, when Nicky, Gardener, and Margaret are brought in to a police line-up to identify the potential killers, Gardener strangely asks that Nicky leave the room. But Nicky is able to see the line-up through an ajar door. He also sees his father and aunt look directly at the men who killed his mother and tell the police that that’s not them.

That’s the first moment Nicky realizes something is wrong.

When he confronts his dad about the ordeal, his dad tells him that Nicky is simply misremembering. But the next day, when Nicky gets home from school early and sees his father and Margaret naked on the pool table, he knows something is seriously up.

Sensing that his son is onto them, Gardner enrolls him in boarding school, but before he can even begin to put that together, a suspicious insurance auditor comes around wanting some questions answered about Rose’s suspicious insurance policy. Oh, and let’s not forget the two guys who perpetrated the murder, who are tired of waiting for their payoff. Yeah, they show up as well.

It looks like whatever plan these two thought they’d pull off isn’t going to end the way they thought it would.

Every serious screenwriter needs to read the first scene of this script. It does five deadly important things right:

Starts the script off with a bang to grab the reader’s attention.

Approaches the scene in a unique way.

It’s intensely suspenseful.

It builds.

It holds tension throughout.

I’m lucky if I read a script where a writer is able to do one of these things right in an entire screenplay. To do all five in one scene shows why the Coens are two of the only people to win multiple screenwriting Oscars.

So let’s go into all of these in detail.

The first one’s obvious. I tell you guys to pull your reader in right away with your opening scene. Here, we open with a murder. Perfect.

The second is what sets the Coens apart from their competition. They’re really good at coming into scenes from a UNIQUE POINT-OF-VIEW. This gives what would otherwise be a been-there-done-that scenario a fresh angle. So instead of seeing the murder from the dad’s or the killers point-of-view, we see it from this kid’s point of view. And since Nicky isn’t sure what’s happening exactly, everything feels fresh and different.

Third is suspense. Remember, the best kind of suspense is to imply that something bad is going to happen, and then you draw it out for as long as you can. We know early that these men are up to no good. So everything that happens before the chloroform plays like gangbusters.

Fourth, the scene builds. A lot of writers want to jump into the climax right away. For example, we’d show the killers screaming and yelling and then gunshots would go off. That’s a really boring way to show a murder. Instead, we start off with Nicky being brought out of his bedroom, then downstairs. We then have a conversation in the living room. We then find out that we’re going downstairs. We then find out that we’re going to be tied up. We then find out that, person by person, we’re going to be given chloroform. Each “stage” or “level” is worse than the last. That’s how you build in a scene.

Finally, we have tension. I feel that too many writers go for instant gratification in a scene. They want to “burst the balloon” so-to-speak. Instead, pretend that your fingers are the only thing keeping the air in the balloon. Hold onto that opening AS TIGHT AS YOU CAN. Keep that tension throughout

Honestly, this first scene should be taught in film school.

And really, the majority of this script could be taught in film school. For example, what do I always say about funerals? DON’T PLAY THE OBVIOUS EMOTION in THE SCENE. Play any emotion BUT the expected one. So after the mother’s funeral, we don’t have Nicky telling his dad how much he misses mom, or a scene where the dad breaks down crying in the middle of the wake. We have Nicky walking with his weird uncle, who’s bitching about how lame the service was. The emotion he plays is ANGER, which works against the expected tone, and therefore makes for a good scene.

And the Coens can always find ways to add tension to scenes so that even the smallest ones have something going on in them. Because remember, the most boring scene you can write is two people sitting or standing across from each other in a generic location talking about whatever needs to be talked about in that scene.

Here, our two killers, Luis and Ira, are bus drivers. Luis, who’s working today, is avoiding Ira because Ira wants to put more pressure on Gardner to get their money sooner. So when Ira shows up on Luis’s route, he demands that Luis step outside for a talk. Luis reluctantly comes outside, and Ira tells him what he needs to tell him.

The scene works better because now you have 20 bus passengers popping out and saying, “Why the fuck are we stopped?” “This isn’t even a real stop.” This turns what could’ve been a boring scene (two people sitting or standing across from each other in a generic location) into an intense one. This is the kind of writing, guys, that top producers notice. They know that writers who know how to do this shit are good writers.

My only issue with Suburbicon was the ending. It came together too quickly. There’s a classic Coen Brothers scene where the insurance agent shows up and tells Gardner he’s onto him where I thought, “Ooh, this is about to get good,” then everything goes to shit quickly and before I knew it, I was at the end. It just felt like we needed more time to get there.

Still, this script shows why these guys are heads and tails above all the other screenwriters out there. Definitely check it out if you can.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[x] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: The more helpless you can make your main character, the more compelling the drama will be. The reason this script is so intense is because our hero is 8 years old and powerless. Even though he knows who killed his mom, he can’t do anything about it, and that’s why we turn the pages. We’re hoping against all hope that he somehow finds a way. To understand why this works so well, switch 8 year-old Nicky out and replace him with a 30 year-old man. A 30 year old man would be able to solve this problem immediately. We’d feel very comfortable with him taking care of the problem. As you should know, “comfortable” in storytelling is the same thing as “boring.” One of the many reasons the Coens can rock the page.

What I learned 2: If something is obvious, you don’t need your character to say it. So let’s say a woman’s husband dies. You don’t then have the woman say, “I can’t believe he’s no longer here. I miss him so much.” Oh really? Wow, I never would’ve guessed that. If it’s obvious, the audience knows. You don’t need to have your character say it so that they get it. This is VERY common beginner screenwriter tell.

The box office is chirping, people.

It’s chirping at you now. Hopefully, you’re paying attention.

The top movie of the weekend was Angry Birds, which took in 39 million worms. This film represents everything that Hollywood wants in a project. Established IP. Something that can sell toys. Something that plays to all audiences.

Unfortunately, it doesn’t help the average screenwriter understand what they should be writing, since established IP is off-limits. If pushed for a lesson here, I’d say that the more age groups your screenplay plays to, the more appealing it will be to a producer, assuming it’s a good idea and well-written.

But what multi-demo genres are left that aren’t dominated by the IP market? I can think of three. Studios will always be looking for a good adventure script along the lines of Raiders of the Lost Ark. They’re always looking for that supernatural or sci-fi comedy type script (think MIB or Ghostbusters). And everyone’s STILL looking for the next Goonies, 25 years later. Kathleen Kennedy says that of the 30 huge movies she’s made, that’s still the one she gets asked about the most. So something in that vein is still available to spec writers. I would caution though that you better bring your A-Game cause I’ve read all the attempts from writers of these scripts and outside of Roundtable, they’re painfully generic. You have to find a new way into these ideas.

The second big release of the weekend is Neighbors 2, which brought in 21 million, along with some more relevant advice for screenwriters. Comedy still represents one of the best chances for an unknown screenwriter to break into the industry and earn millions of dollars quickly. Come up with a smart (preferably ironic) comedy idea, sell it, and when it does well, reap the benefits of its subsequent sequels.

That brings us to the most complicated major release of the weekend, The Nice Guys. The Nice Guys is the screenplay that serious screenwriters believe there should be more of. It doesn’t fit into any genre or even sub-genre. It’s unique. It’s fresh. But nobody went to see it, including, I’m betting, a lot of the screenwriters who say there need to be more movies like it.

This is the hypocrisy that bothers me about the anti-Hollywood crowd. They cry foul when their weird anti-narrative screenplay doesn’t get noticed. I then ask them if they’ve seen [latest low-profile indie movie] and their answer is almost universally “no.”

So if they’re not paying to see the few anti-Hollywood movies that DO make it through the system, why in the world would they expect anyone to do the same for their movie? It becomes painfully clear that they’re not supporting unique films. They’re supporting THEIR unique film.

This problem permeates a huge swath of the screenwriting community. They think they’re different, that they’re special, that their weird little script is somehow going to be the one that everybody goes to see. When a movie that has one of the biggest movie stars in the world, Ryan Gosling, promoting the hell out of it, and was still barely able to make 10 million dollars, you have to understand that THAT’S why studios are so terrified to take chances on offbeat little films like this.

I mean answer this question seriously. Would you have put up your money for The Nice Guys?

Another major spec release was last weekend’s Money Monster, a film that represents a key issue with the spec market at the moment, and why fewer and fewer of these movies are doing well. A spec script is meant to keep a reader’s attention from start to finish. There can’t be any slow parts.

This necessitates such things as a HUGE idea, tons of urgency, and heightened variables – all things designed to keep a bored reader awake. Unfortunately, this isn’t necessarily a recipe for a great film. A great film creates some sort of emotional connection with the audience.

And emotion requires things that lie in opposition to a reader-friendly script: Character development, relationship development, the occasional slowing down of the narrative. None of those things play well on the page unless you really know what you’re doing.

As a result, we get movies like Money Monster, which at one point in time would’ve had a 30 million dollar opening. Now, with a major effects-driven film to compete with every week, the script needs to do more than merely move. It needs to move the audience. And the “Max Landising” of this craft discourages against that.

The most successful spec story of the year is Cloverfield Lane (remember that it was originally a spec script before they turned it into a Cloverfield film). The 70 million dollar grossing contained horror flick managed to strike the perfect balance between a tight urgent story and characters with some actual meat to them. This allowed us to feel some emotion, which helped strike the perfect balance between “event” and “experience” so many spec screenplays lack these days.

Look, moving fast to please a reader while slowing down to move a reader is always going to be a challenge. You’re literally incorporating things that work in direct opposition to one another. But that’s why the screenwriters who carve out careers in this industry get paid so much, because they’re able to find that balance. Keep that in mind as you’re writing your “Scriptshadow Write a F%$&ing Screenplay” scripts.

Make sure to tune in next Monday as we’ll be revealing the Top 5 scripts in the Scriptshadow 250 Screenwriting Contest, held in conjunction with Grey Matter. We’ve already begun to contact the finalists. And for the winner, it’s probably going to change their lives. So can’t wait to finally share!

Genre: Horror/Comedy

Premise: When an ice cream social results in a deadly outbreak spreading throughout a nursing home, one elderly resident must overcome his own post-war trauma to battle the undead and prove himself to the woman he loves.

About: Hello. My name is Walter Melon (no jokes, please. Believe me, I’ve heard every fucking one of them). I’m 76 years young and an aspiring screenwriter. At this point in my life I’ve had plenty of experiences to draw from – fought in Vietnam, married three times (and divorced three times, thank Christ, though that first one was a hellion in the sack if I’m being honest). I was a tugboat captain on the mighty Mississippi, did a little production work on some adult films in the mid 60’s and even tried my hand at circus life. And let me tell you, those goddamned sideshow freaks think they’re the cat’s pajamas, treating us normal folks like we’re the wierdos! Lobster Boy my asshole. That motherfucker was a…sorry. I can get pretty worked up as you can see. Old wounds never heal. They fester, let me tell you. But I tend to ramble as I get on in years. Like I was saying, this is my second screenplay (my first was a World War 2 yarn, but I didn’t really know what I was doing at the time and it turned out to be a real piece of shit, so I don’t really count that one.) This story here is based on a true experience, one that involved myself and my best friend Albert Miller – the man who saved Picket Farms Nursing Home. Well, fact of the matter is, he didn’t really save but a handful of us – most of the residents were killed. But he saved my hide – more than once. And I thought his story needed to be told. He may be a deaf old bastard, but he’s one tough sonofabitch and I’d walk through fire for that man. I’d love to hear what the younger generation thinks about my latest effort. Thanks to anyone for taking the time.

Sincerely, Walter Melon

PS – Did I mention this was a true story? Hell, at least I think it is. I can’t remember shit anymore.

WM

Writer: Walter Melon

Details: 91 pages

It all comes down to a simple question.

Am I still reading because I have to or because I want to?

If there were no review to put up today, would I still care about what happens enough to read to the end? I’d say that 98% of the time, the answer to that question is no. And writers don’t think about that. They think that their script deserves to be read because they put a lot of effort into it. When in reality, the only reason your script deserves to be read is if you’ve come up with a story compelling enough that people will want to keep reading it. You’ve thought through each section, each scene, each moment, and you’ve asked yourself, “Are they still interested right now?” And if there’s doubt in your mind that they are, you follow that up with, “Why might that be?” And then you fix the problem.

For example, a good writer knows that if he has to come up with an extensive exposition-heavy scene, that could present a hiccup in the reader’s enjoyment. So he asks, “How do I fix that?” He could strip as much exposition out as possible. That could help. He could split the exposition up, so some of it comes now and some of it comes in a later scene. That should help keep the momentum going. But the best writers say, well how can I ALSO make this scene entertaining, as opposed to just information? So they might add some conflict between the characters to make the scene more fun.

The opening of Fargo (the movie) is a great example. That scene where Jerry Lundergarten walks into a bar and discusses the kidnapping of his wife with two criminals is pure exposition. It’s setting up what’s about to happen in the story. But we don’t even notice the exposition because one of the criminals is bitching at Jerry for being an hour late and the other looks like he’s about to rip somebody’s head off within the next three minutes. There’s tension and anger and conflict in the scene. The exposition is invisible.

I read too many scripts where writers don’t make that adjustment. They think “The reader owes me this time.” I even had a writer defend himself once after one of the most blatant exposition-heavy scenes I’ve ever read, by saying, “Well yeah, that was my Exposition Dump Scene.” As if he was somehow owed four minutes of boredom from the reader. I’ve seen four minutes of boredom derail scripts before. Never take four minutes lightly.

I don’t even know why I’m focusing so much on exposition because there are plenty of other ways to bore a reader. Like having three scenes in a row where the story doesn’t move forward. Or where the characters aren’t talking about anything interesting. There are a lot of ways to be bad. I guess the point I want to make is, you must monitor your reader’s projected reaction after each and every scene so that you have a strong argument that you aren’t boring them.

You aren’t owed anything with a script. Nobody cares that you worked 500 hours on it, or 7 hours if you’re Max Landis. All they care about is, “Am I not bored right now?” The second the answer to that question is “no,” you’re toast. So pull out all the stops to make sure you’re never placed in the toaster in the first place.

Speaking of food, how did Sundae, Bloody Sundae fare under this criteria?

The Picket Farms Nursing Home is usually a fun place for its age-advanced residents. Even though one of his best friends just died, 70-something Albert has a nice flirtationship going with 70-something Isabella, and is looking to impress her this weekend while her granddaughter is visiting.

Unfortunately, Albert’s plan to Netflix and Chill is ruined by some Netflix and Kill. The dickhead administrator here at Picket Farms, Gil Tuttle, ordered the cheapest most rancid ice cream you can imagine for Sundae Movie Night, and one serving of that ice cream turns people into flesh-eating zombies.

While Albert, his buddy Walter, Isabella, and Picket Farms rabble-rouser, Claire, sputter around for a random evening of trouble, their co-residents are busy Ben & Jerrying themselves into old-person zombies. They’ll now have to use their smarts to find a way out of the building, since they definitely can’t use their strength, quickness, or anything that has to do with movement. If you’re thinking this won’t go smoothly, I’d tell you that you are correct, my friend.

So does this survive that all-important question I brought up?

Am I reading because I have to or because I want to?

Sadly, it was because I have to.

If it was up to me, I would’ve been out around page 15. But not for any of the reasons I mentioned above. In truth, Walter keeps things moving pretty quickly here. I’m not sure there’s a scene in this script that doesn’t deserve to be there. But here’s why I tapped out.

The zombie genre is the most ubiquitous sub-genre in all of screenwriting. So when I read a zombie script, it has to be really fucking amazing. To Walter’s credit, he’s found a subject matter that hasn’t been explored in zombie storytelling before (at least that I know of). But see, that’s not enough for me. And it isn’t enough for most people.

When you’re playing inside the same sandbox as everyone else, you need to be CLEVER. Moving the zombie genre into a new arbitrary location isn’t enough. Because to me, anybody can do that. Anybody can place a zombie movie in a law firm (never been done before) or IRS headquarters (never been done before) or at the top of the Empire State Building (never been done before). But what’s clever about that? You’re just finding a different place to place zombies.

That’s why I hated that Boy Scouts vs. Zombies abomination. What the fuck was that? It’s almost like the writer spun the “random subject matter” wheel, it landed on Boy Scouts, and he just added zombies to it.

Now Walter (and others) may come back at me and say, “Carson, aren’t you overthinking this? Old people turning into zombies is funny!” That’s a fair argument. But I’m trying to place you in the mind of the seasoned reader or producer who sees a new zombie script on their desk every day. Those people aren’t easily swayed. Having them chuckle at a premise isn’t the same as buying one. They’re looking for something more, especially because yesterday they probably read a zombie movie that takes place in a high school. And the day before that a zombie movie that takes place in Ikea. Your funny premise stops looking as funny when placed next to other sorta funny premises.

The best zombie movie of the past 10 years – and also the most profitable, which is the main thing producers are looking at, mind you – was Zombieland. Why? Because it was clever! It explored the mythology in a unique way. So did 28 Days Later. It created a different kind of zombie that we hadn’t seen before, one that was more dangerous, scarier. And the most clever zombie movie I’ve ever seen is this short film. Unless you’re funding your zombie movie yourself, that’s the level you need to aspire to.

Having ranted about all of that, how was the script?

For a zombie script, I thought the character work was pretty good. Each of the main characters was colorful and memorable. They all seemed to have something going on. For staff, it might have been a social security scam. For residents, it may have been lying about being a war hero. So the characters were more than just munch-cushions.

And there were clever uses of this unique situation. For example, old people are slow. Zombies are slow. So in a scene where a zombie is chasing an old person down the hallway, it’s the slowest chase in the history of chases. I could see that playing like gangbusters onscreen.

And there were smart little plot threads. For example, Isabella’s granddaughter gets lost, which gives our characters something to achieve (A GOAL!). Whenever you give your characters a strong goal, chances are, at the VERY LEAST, your script will be readable (up until that goal is met). Who doesn’t want to see if the defenseless little cute girl gets rescued?

Walter also gets bonus points for a marketable image to sell the movie – a giant bloodied bear costume. Loved it.

But this is the thing about concept – and the reason I put so much emphasis on it when we started the Scriptshadow Write-a-Screenplay Project a month ago. If the reader isn’t on board with the concept, it’s really hard to make them interested in what’s happening inside of that concept. It’s still possible to win them over. But it’s harder. Which is why you want to road test that concept ahead of time.

With all that said, I admit that people more into zombie flicks, particularly zombie-comedies, might like this. For what it is, it’s a fun crisply-written screenplay. Unfortunately, it wasn’t my thing. :(

Script link: Sundae, Bloody Sundae

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Sundae Bloody Sundae is a good reminder that screenplays don’t start on page 1. They start long before that. Make sure things have been happening before your story begins. That way, your characters feel like they’re living their lives, as opposed to being born the second the writer types, “FADE IN.” For example, Rose and Tuttle have their social security scam that they’ve been profiting from for years. That started long before this script began. You want to do that with as many characters as possible. Give them things they’ve been doing before your script started.

Guess what time it is? It’s time to venture into the SECOND ACT!

NOOOOOOOOOOO!!! you say.

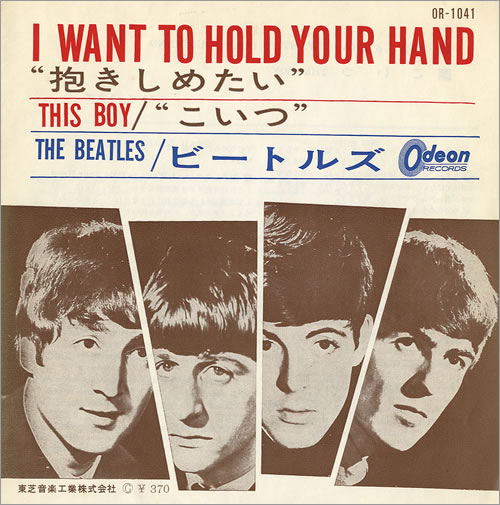

Don’t worry, my screenwriting salsolitos. Just like The Beatles, I’m going to hold your hand.

For those of you new to the site or you infrequent visitors, I’m doing a 13 week “Write a Screenplay” Challenge, where I guide you through the process of writing a screenplay step by step. If you missed the first few weeks, you can find them here:

As of today, you should have written 21 pages. That means you’ve completed your inciting incident (located near page 12-15) but are not quite at the end of your first act (page 25). So today, we’ll be covering the break into Act 2, as well as the first sequence of Act 2.

Now I heard some grumbling last week about 3 pages a day being too difficult. Come on, guys. Seriously? That’s one scene. You only have to write a single scene. You’re telling me you can’t write a scene in a day??

Maybe this will help. Brendan O’Brien and Andrew Jay Cohen said that when they were trying to figure out their script, “Neighbors” with director Nicholas Stoller, they’d pitch him a bunch of directions they could go, thinking he’d pick one and let them go write it.

Instead, Stoller would say, “Well let’s try that version right now.” “What do you mean right now?” they’d ask. “Let’s sit down and write it and see if it works?” “You mean write the script… now??” “Yeah.” And they’d sit down and write the whole thing over a few days. If it didn’t work, they’d try a different take.

The point is, you’re capable of one scene a day. Don’t be a perfectionist. Just write.

Okay, on to this week’s challenge. You’ve got between 4-8 pages before the end of your first act. If your hero is in a refusal of the call situation (Luke Skywalker claims he can’t join Obi-Wan because he must stay and help his Uncle on the farm), this will be the last bit of resistance your character experiences before accepting that they have to go on their journey (pursue their goal).

If your hero isn’t refusing the call, this is the last few pages of logistics before they pursue their objective. Indiana Jones don’t refuse no call. He just packs his bags and prepares for the fun. If your character doesn’t have any say in the matter, the forces of the story will simply kick them out on their journey, much like a bird kicks its babies out of the nest to see if they can fly. Tough love, amirite?

Now in some cases, a journey is literal. Rey’s journey in The Force Awakens takes her across the galaxy. Tom Cruise and Dustin Hoffman take a road trip to Vegas in Rain Man. Joy has to travel deep into the recesses of Riley’s mind in Inside Out.

Other times, it’s more symbolic. As long as your character is constantly pursuing something, even if they’re stationary, it’s considered a journey. To use the aforementioned Neighbors as an example, our heroes may be inside the same house the whole movie, but their “journey” consists of trying to get the frat next door kicked out.

So the first 15 pages of the second act are a unique time in a script. Your heroes are going off on their journey, but since we can’t throw the kitchen sink at the audience right away, this section tends to be more of a “feeling out” period for the characters. Maybe they’re feeling out each other (“Bad Grandpa”) or feeling out the situation (In a heist flick, the characters might scout out the bank they’re planning to rob, or the team they’re trying to recruit).

The late Blake Snyder, whose book “Save The Cat!” is somehow still the best selling screenwriting book out there despite Scriptshadow Secrets being available, famously termed this section, “Fun and Games.” Since Blake mainly wrote comedies, this was meant to define the period in the script where you showed off the promise of your premise.

The best example of this is probably super-hero origin stories. This is the moment when Spider-Man or Ant-Man first get their powers and play around with them. But it can also be applied to other genres. In Jurassic Park, it’s seeing the dinosaurs for the first time. In The Equalizer, it’s when Denzel starts administering justice on the locals.

If all of this is confusing, however, or it doesn’t feel like it applies to your movie, don’t worry. There’s a backup. What’s that backup?

SEQUENCES

Divide your script into a series of eight 12-15 page sequences. You’ve already finished the first two sequences. That was your first act. Now you’re on your third. You have to fill up 15 more pages. The easiest way to do this is to give your characters an objective they have to meet by those 15 pages. That way, you don’t have to worry about this giant chasm-filled void of a second act. You only have to write 5-7 scenes getting your hero to the end of that sequence goal.

A good example is the Mos Eisley sequence in Star Wars. We’re officially on our journey into the second act. What’s the goal here? The goal is to get a pilot and get the fuck off this planet, since the Empire is chasing us. We experience a series of scenes where our characters come to Mos Eisley, enter a bar, look for a pilot, get a pilot, head to the ship’s hanger, get chased by stormtroopers, then leave. That’s a sequence right there, folks. That’s all you have to do.

You can even use this for non-traditional scripts. Room is a movie that’s basically two long acts. It’s divided in half. But if you look closer, you’ll notice that there are sequences to give the story structure. For example, the fourth sequence of that movie (which would roughly be page 40/45 to page 52/60) is Ma (Brie Larson) planning the escape. That’s a sequence folks. It’s got a goal. It consists of a series of scenes. This stuff isn’t rocket science.

Gravity is a great movie to study for sequencing. It’s evenly broken down into a series of sequences where Sandra Bullock constantly has to get to the next destination, which usually takes between 10-15 pages (no, that is not an excuse to procrastinate!).

So that’s this week’s challenge, guys. You have to get 15 pages into Act 2. Seeing as we finished on page 21 last week, that means you only have to write 19 pages this week, which is LESS than 3 pages a day. Which means no more complaining. I’ll see you next week, with 40 total pages completed. And that’s when we head into the HEART of the second act. Ooh, I can’t wait for that. And by “can’t wait,” I mean, “Shit, that’s going to be terrifying.” Seeya then!

Genre: Drama

Premise: After a priest stumbles across the execution of a Mexican family who were trying to cross the border, he finds himself hunted by the killers.

About: This script sold two years ago in a mid-six-figure deal. The writer, Mike Maples, has been at the game for awhile, with his first and only feature credit, Miracle Run, being made back in 2004. Padre was pitched as being in the vein of No Country for Old Men and A History of Violence. Like I always say, guys, find those buzz-worthy movie titles to compare your script to. Whether it be “Fargo on the moon” or just, “This is the next Seven.”

Writer: Mike Maples

Details: 100 pages – undated

There are two types of screenwriters trying to break into the business. There are the ones who grew up on big fun movies who want to bring those same good vibes to the masses, and there are the ones who want to say something important with their work, who want to make “serious” films.

Take a guess which ones have an easier time getting into Hollywood.

That’s one of the first pieces of advice I’d give to anyone getting into screenwriting. Write something marketable. Yet when I run into one of these serious types, the suggestion of marketability is akin to asking them to copulate with a rhinoceros. They feel like they’re “selling out” if they even consider the masses while writing in their vintage 1982 moleskin notebook. It’s almost as if they’d prefer wallowing in obscurity for the rest of their lives, attempting to push that Afghani coming-of-age story, than break through with a strong horror premise AND THEN write their anti-Hollywood film.

Well if today’s script tells us anything, it’s that it IS possible to sell a thoughtful more serious spec. It doesn’t happen often. But it can happen. Let’s figure out what today’s writer did that was so special.

40 year-old Gideon Moss is a priest who lives just north of the Mexican border. While everyone else in the area is furious about illegal immigrants crossing into their country, Gideon regularly delivers water and food to those at the end of their journey.

One day, while on a run, he stumbles across a recently murdered family of Mexican immigrants. A quick look around and he spots, in the distance, a couple of locals staring at him. Doesn’t take much to add 2 and 2 together.

Figuring they’ve been made, the men, a part of a bigger militia, barge into Gideon’s church later that week during a sermon, round up him and all the Mexicans, take them to the desert, bury them alive, then crucify Gideon on a cross. Gotta give it to these guys for creativity.

Left to bleed out, Gideon escapes, and starts hunting the gang down one by one. Oh, there’s one last problem I forgot to mention. The militia? They’re all cops. So it’s not like our pal Gideon can ask for a helping hand. Lucky for him, and unlucky for the baddies, he has a very military-friendly past.

Okay, so this isn’t exactly an Afghani coming-of-age story, but it fits a rule that I push on writers attempting to write “serious” films. Make sure there’s at least one dead body. While there may be a temptation to mirror real life and call your script ‘realistic,’ the reality is that film is larger than life. You have to have at least one larger-than-life element in your story. A dead body fits that criteria.

Also, if you’re going to write one of these serious scripts, you need to be descriptive. You need to have the power of picture-painting. Your world is decidedly less exciting than 12 superheroes battling each other on an airport tarmac. So you have to make up for that in your ability to place your reader inside your world. A truck can’t just drive. It has to exist, as Maples shows us here: “A rooster tail of dust billows behind the truck and hangs in the still scorched air.”

It should also be mentioned that if you’re going to write this type of script, you have to have the skill to actually pull it off. The most painful scripts to read are the ones where writers without any skill try and weave their way through complex descriptive sentences. For example, they’d re-word the above into… “The truck lampoons the stretch of road with forest trees all around it and shifts into gear like a rocket out of hell.” Honestly, I read a lot of lines like that.

Also, you have to have dialogue skills for these scripts. When someone offers to help Gideon, despite the risks involved, he doesn’t reply, “No, your life is too valuable,” he replies, “Leave it be. Your box is thirty years down the line. No use taking a short cut.” That’s a professional line of dialogue right there. Or later we get this exchange, which takes place between the badass villain and one of his dim-witted minions: “What the fuck is this?” “You just squandered five of the ten words in your vocabulary, son. Keep the rest for later.”

Padre also utilizes two tropes that tend to work well in film. The first is the priest who’s not so priestly, and the second is the cop who’s not so friendly. As we like to preach around these parts, always look for irony in your story. Corrupt cops are as ironic as it gets. So are murdering priests. Usually, you only see one of these in a movie. It was fun to read a script where we got both.

And there were just little professional spikes that set this apart from the average amateur script. For example, a little girl is killed in that scene where the bad guys round up everyone in the church and bury them alive. Now normally, a writer would think that was enough. Nobody likes to see a little girl die. We’ll hate the bad guys even more and want to see them go down.

But Maples makes sure that we SET UP A SCENE WITH THIS GIRL EARLIER. So one of the first scenes is Gideon visiting a nurse friend at the hospital. The nurse gives him drugs to pass to the little girl, who’s sick at home because she’s illegal and can’t afford hospital care. Gideon delivers the medicine to the girl, so that we know her and care about her (not to mention doubles as a Save The Cat moment!). That makes her later death a thousand times more impactful. Amateur writers rarely think to do this sort of thing.

If there’s a knock against the script, it’s that it feels a little familiar. There are usually 3-4 of these kinds of scripts on the Black List each year. And I wasn’t a fan (spoiler) of the revelation that Gideon used to be a Black Ops soldier. It seemed like a lazy choice, and honestly, I don’t think it was necessary. Gideon comes off as badass enough that you don’t need to make him even more badass with some backstory title. But outside of that, this was a strong script.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: If you’re going to write a script like this, be honest with yourself and make sure your writing is at the level required to pull it off. I’m not saying you don’t have to know how to write to write “Neighbors.” But the skill level of putting words together is decidedly less important with scripts like Neighbors or Deeper. With drama, you will be judged more harshly on your writing ability, because your job is to set a mood and a tone with your writing, something that takes a lot of time and practice to master.