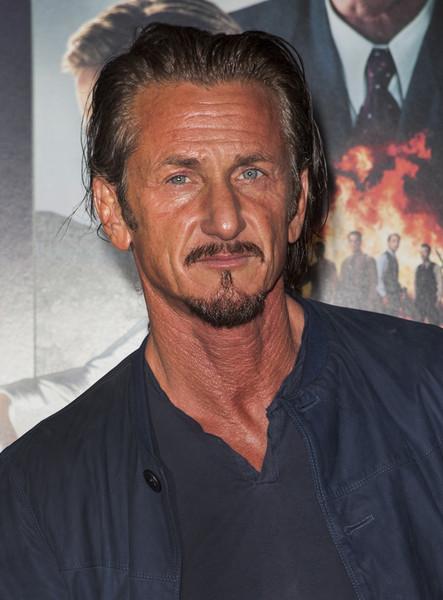

My new best friend Sean and I are hanging out later. So I just wanted to post a picture of him.

My new best friend Sean and I are hanging out later. So I just wanted to post a picture of him.

One of the most frustrating things about going through all these scenes was reading scenes that just didn’t go anywhere. Nothing was happening. And here’s where you see a major difference between experienced screenwriters and new screenwriters. It’s the difference in their interpretation of the phrase “something happens.” In a script, in every single scene, in order to keep a reader riveted, something NEEDS TO HAPPEN. Beginner writers say, “Hey, that conversation between me and my co-worker about our douchey boss was kind of funny. I’ll put that in a script.” And they do. And they don’t understand why no one responds to it. It was cute. There were a few funny lines. And it was life, man! Real-world shit! The reason nobody cared is because nothing happened.

Experienced writers know that “something happens” means ratcheting up the stakes and bringing something big to the table, a scene where what people say actually matters, where there are consequences to people’s actions! If they’re going to write a scene about two co-workers, one of them is going to have a gun hidden in her jacket. She and her co-worker had an affair. He’s broken it off. She’s been e-mailing and texting and calling him to no avail. He barely responds to her. Echoes of Fatal Attraction. She’s finally convinced him to have lunch with her. She’s brought a gun to their little chit-chat and is considering using it if the conversation doesn’t go well. Now, something is happening.

There’s an old saying with writing screenplays. It goes something like this: Your story should be about the most important thing that’s ever happened to your character in his life. In other words, if what you’re writing about isn’t even the biggest thing that’s happened to your hero, why do you think we would be entertained by it? I think you can apply this approach, at least partially, to scene-writing. The scenes you write should be the biggest 1, 2, or 3 things that happened to your character that day. There will be exceptions to this for sure. But if you’re picking your best scene in the whole script? One that really shows off your chops? And it doesn’t even seem (or barely seems) like it was the most important thing that happened to your character that day? How do you expect a reader to be impressed?

But here’s the real killer. The writers who WERE able to write a scene where something was “happening?” The ones who avoided that pothole? They often made the mistake of writing the scene in the most predictable way possible. Those are some of the hardest scenes to read. Because here we are. This huge scene is laid out before us (i.e. Hero finally confronts his mother who left him as a child), and it… goes… exactly… according… to plan. He asks mom why she did it. She takes a deep breath. Says she doesn’t know. She thinks about it. Talks about how it was all too much for her. I mean, WE’VE SEEN THAT SCENE BEFORE! We’ve seen it a billion times.

I just don’t understand why screenwriters don’t realize this. Why they don’t realize that we’ve been down that road before. As a writer, it’s your job to know the reader’s expectations, and then go in a different direction. That way you surprise them as opposed to bore them. This to me, is what all the best writers do. And it’s one of the easiest skills to learn. You don’t have to be a master storyteller to do it. All you have to do is recognize the way a scene typically plays out, and go another direction. Even if that direction turns out to be a bad choice, at least we’ll applaud you for not taking the obvious route.

Another thing that shocked me is I don’t think I read a single “Hitchcock bomb under the table” scene out of all the submissions. Someone can correct me if I’m wrong (Miss SS read a few submissions so maybe she did) but I didn’t see one. This is one of the EASIEST ways to write a good scene. You should have 2-3 versions of this scene in every script you write. Maybe more depending on the genre. Essentially the idea is, if you have two people talking at a table, it’s boring. But if you tell the audience there’s a bomb underneath the table, a ticking bomb, then all of a sudden the scene becomes interesting.

This is where Sean and I met. Memories.

This is where Sean and I met. Memories.

You can apply this to a scene in a million different ways. I just did above. The two co-workers talking, one of them secretly has a gun they’re planning on using. That’s a Hitchcock scenario. The scene with John McClane and Hans on the roof in Die Hard. We know he’s the bad guy. John doesn’t. That’s a Hitchcock scenario. A 17 year old girl is going out with a 35 year old biker that nobody in her family likes. There’s a big family dinner. The girl and the guy are planning on dropping the bomb that they’re getting married. That’s a Hitchcock scenario. If you want to win a scene contest, write a good “Hitchcock scenario” scene and, at the very least, you’ll be in the running.

Not every scene has to be a world-beater. Comedy is different. As long as you’re funny, you can get away with not much “happening.” But you have to be a freaking dialogue master to pull that off. You have to write dialogue that SINGS. When you give your script out to people, you better always be receiving the compliments “Your dialogue was great” and “I couldn’t stop laughing.” If not, do not try to rest on your dialogue alone. But to be honest? Why not do both? Why not create those intense pressure cooker situations that make scenes pop ALONG with the comedy? That’s why Meet The Parents was so good. They did such a great job setting up the stakes of that dinner scene. With how much Ben Stiller’s character wanted to impress Robert DeNiro’s character (his girlfriend’s father). They made it clear that everything was riding on his performance at that dinner table. So each word spoken was a potential death trap. Then, when they’re bantering back and forth about whether cats have nipples, it’s not just the writer trying to show you how funny he is. It’s Ben Stiller’s character digging a hole the size of the Grand Canyon trying to find a way out of his continued screw-ups. When we’re emotionally invested in a scenario, we’ll always laugh more.

Despite my passionate plea for better material, this week was really cool for me because I usually read everything within the context of the script. This placed my focus SOLELY on the scene. The scene had to live or die on its own. And it made me realize that each scene, in its own way, is like a script. It’s got its setup, its conflict, and its resolution. It needs goals, stakes, and urgency. It needs conflict. But most of all, it needs to matter. We need something important to be happening or else we’re going to tune out. And you guys need to treat it like that. Treat every scene with pride, like it’s its own story, and try to write the best story you possibly can. If you do that, the next time I hold one of these contests, you won’t have to choose a scene from your script. Because every one of them will be great.

Genre: Comedy

Premise: (from me – based on limited info) A frustrated middle-aged family man who hates dealing with all of life’s bullshit finds out about a man who solves people’s problems by jumping into their minds. He enlists this man to eliminate the problems in his life, with unexpected consequences.

The Setup: JIM (our schlub) hates his job, his marriage, his life – he’d rather just avoid everything. So when he meets a guy in a bar who gives him a number of another guy – BOB – who can help him do just that, Jim is intrigued. He calls the number, and this mysterious, intimidating Bob character tells him to be at his place in one hour. Here’s the scene that follows…

Writer: Ethan Furman

Details: 7 pages

I think people outside of Los Angeles believe that we Los Angelinos walk around bumping elbows with celebrities all day. You take your dog for a walk, there’s Tom Cruise grabbing a hot dog at Pink’s. You grab a bite at Chipotle, oh, there’s Angelina Jolie, complaining about the lack of guac on her burrito bowl. And when you get home, Ken Jeong is sitting on your steps practicing new characters via Skype with Bradley Cooper.

Sadly, celebrity sightings are few and far between unless you’re one of these obsessive stalker types who go to all the events and track their celebrity buddies’ whereabouts on Twitter. But if you’re just walking around randomly, you ain’t going to see many celebs. So when you DO see someone big, it’s kind of cool. And today, for the first time in a long time, I had a celebrity sighting, and it was awesome.

The setting? El Carmen. A pleasant Mexican dive bar/eatery. There were a total of 10 people in this bar. And then who walks by? Just marching forward like it’s nothing? Sean Penn! Sean fucking Penn. And let me tell you this: This guy looked like just as much of a badass as he does in the movies. He slid into a back booth with some ladies he was (I’m guessing – but who knows, since it’s Sean Penn) meeting there. I think the reason it hit me so hard was because it was such an empty place. And so it’s odd to spot a big celebrity around no other people. It just feels off. Like a crew of 50 people should be following him around or something. Anyway, it was rad.

What does this have to do with Scene Week or today’s scene? ABSOLUTELY NOTHING! I just wanted to tell you my cool Sean Penn story. And now that I think about it, it wasn’t that cool at all. I just saw a man walk by me. It would’ve been a lot cooler if I had tried to talk to him and got decked in the face. I’ll try that route next time.

So, what’s today’s scene about? Glad you asked. Our hero, Jim, comes to this guy Bob’s house. As he walks in, hookers stumble out. When he gets to the living room, Bob’s playing a grand piano in shorts, snorting coke. After Jim’s WTF reaction, Bob asks him why he came. Jim tells him he has to fire a guy at work that he likes and doesn’t want to do it. Bob responds by explaining to Jim his super-power. He can jump into people’s minds! That means Bob can jump into Jim’s mind, fire his friend at work, and an hour later, Jim won’t remember a thing. He can continue on with his life guilt-free. Hesitant at first, it’s clear that Jim is intrigued. Let the craziness begin!

Okay, so what’s so great about today’s scene? Well, here’s the thing. This kind of scene, in my opinion, is the easiest kind of scene to write. It’s the “Premise” scene. It’s when you essentially reveal the concept and hook of your story. And in that sense, it begins the story. Because once your hero is introduced to this moment, the train starts moving.

So in that sense, Ethan kind of cheated. There is no subtext here. There are no twists. There’s no dramatic irony. There’s nothing in this scene that’s difficult to do and shows skill. But here’s the reason I included it. Out of all the scenes I read this week, it’s the only one that inspired me to want to read more. I thought this was a pretty nifty concept and one I hadn’t seen before. I wanted to know what would happen when this guy entered our hero’s head. I could see the story possibilities flow. One hour, your life is fine, then you wake up an hour later and everything in your life is backwards. Or Bob screws up the first time, has to mind-jump again to fix it, messes up even more, tries to fix it again, keeps making it worse. You could do a lot of stuff with this premise.

But let us get back to the actual scene. Just because Ethan picked the easiest kind of scene to write doesn’t mean it’s guaranteed to work. I’ve seen thousands of easy scenes get screwed up. In any scene, it comes down to one thing: Are you interested in the characters and what they’re dealing with? If you’re not, the scene isn’t going to work no matter how well it’s written.

I liked Jim. His situation is relatable. And I thought Bob was fun (as well as mysterious). I liked how he used to be an Olympic athlete. I liked how he was casually playing the piano when Jim walked in. I thought the hookers and the cocaine were a little cliché, but they were organic to the character so I went with it.

Assuming you’ve got the character issue taken care of, the next step with a scene like this is dialogue. While I’m not going to say this dialogue was amazing, the combination of it and the intriguing premise was enough to keep me entertained. I will say I like when characters are played against type – when their actions and disposition don’t match up with the way they speak. And we get that with Bob, who’s presented as kind of a wild guy, yet is really smart and on point when he speaks.

“Well, enough with the engaging small talk, Jim. You’re here because you have a problem.” “Um. Yes. I do.” “And what is the nature of this problem?” “Well, uh, specifically, my boss is making me fire my assistant.” “And why is that a problem?” “Well…I like him a lot. I feel sick about it.” “Ah. So you weren’t being specific.” “Excuse me?” “You said your problem was that your boss is making you fire your assistant. But in reality, the specific problem is that it makes you sick to do it. It’s something you don’t want to do.” “Yes. I guess that’s right.” “Yours is a problem of guilt. Guilt makes us feel bad. Hurting someone – firing your assistant, breaking up with your girlfriend – these things must be done sometimes. But the guilt is very unpleasant. Correct?”

That sort of unpredictability, of Bob seeming like a doofus then showing he’s quite intelligent, in combination with the suspense of finding out what it is Bob does… that kept me invested.

I also liked how Ethan anticipated expectations and flipped them on their head. Bob: “Here’s what’s going to happen, Jim. I’m going to explain what it is I do. You’re not going to believe me. Then there will be this little back and forth about whether I’m crazy, full of shit, et cetera. I like to skip over that part, because it bores me, so we can just get down to the business of solving your problem. You with me?” It was lines like this that, again, kept me intrigued.

I think my only suggestion for Ethan is to shorten up the scene. Whenever you’re dishing out exposition, even if it’s fun exposition (that’s what I call premise exposition, since it’s usually the fun part of the script, unveiling the premise on the audience), you MUST BE AS SUCCINCT AS POSSIBLE. Because no matter how interesting the exposition is, if the reader feels like they’re being talked to for too long, they start getting bored. And after the “climax” of this exposition, Bob revealing how this whole mind-jumping thing works, I didn’t have enough energy left to listen to Jim’s query (“If your mind is in my body, then where does my mind go?”). The answer with the “mind spa” stuff was cute, but again, you gotta know when you’ve hit your scene’s climax and then get out. It’s like the end of Rocky. The fight’s over. We don’t need to see Rocky shower.

As for what you do with that extra exposition, which might be necessary, is you just put it in a later scene. For example, right before they’re about to mind-jump, Jim can realize: “Wait a minute! What happens to my mind while you’re inside of me??” And Bob answers the question then.

So yeah, I liked this. Again, it had some cracks, like all the scenes this week. But it passed the biggest test of all. After I read it, I wanted to read more. What did you guys think?

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Avoid the cheap jokes. The gay jokes. The hookers. The coke. Those are cheap laughs. And what I mean by that is, you’re going to get a laugh from some readers, but it will be a hollow laugh. If you can find a new angle on one of these jokes though – a way to make it fresh, then by all means use it. For example, I read a script once where gays were discriminating against a guy for being heterosexual. It was a clever 180 on a tired joke so it worked. Just know that the cheapest jokes – they’re the ones readers see ALLLLL THE TIME. And if you’re a good writer, you don’t want to be like everyone else. Do you?

Genre: Sci-fi

Premise: (from me – based on limited info) A group of shuttle astronauts find the world scorched and dangerous upon returning home.

The setup: The year is 2045. The space shuttle Excalibur has completed its routine satellite conservation mission only to find that the Earth has perished overnight- crystal blue waters replaced by dark crimson, white clouds now a gory hue, continents indiscernible. After much debate, and resources depleting, they have no choice but to go down. They arrive and

find themselves in a deserted wasteland, dead and burnt cities, a graveyard civilization. Lifeless.

Writer: Rzwan Cabani

Details: 7 pages

I think one of the hardest things about scenes is that, if you’re doing your job right, you’re trying to cram key information into every one of them, as you want each scene to push the story forward and tell us a little bit about your characters. The problem is, when writers do this, they often go overboard with this information, or they convey it in the wrong way, stilting the scene and making it more about information and character development than pushing the story forward.

And that’s the trick. First and foremost, every scene should be about PUSHING THE STORY FORWARD. All the other stuff should be hidden inside of that, instead of taking precedence. There are exceptions of course, and this approach will be treated differently in an action movie than, say, an indie character piece. But for the most part, it doesn’t matter what kind of movie you’re writing. The scene should exist primarily to push your characters towards their current objective, not bore us with information.

This happened with the most recent amateur script I read. A large number of scenes existed only to show two characters in a room talking about things that did happen, were happening, or were GOING to happen. Information-heavy scenes like this can be the death of a screenplay (and one of the easiest ways to spot amateur writers). In general, you want your characters chasing goals or leads or objectives that have them moving towards the next plot point. Along the way then, you cleverly drop in that information (what’s often called “exposition”), so it’s not the focus of the scene, but rather a secondary aspect of it.

I’d say a good 50% of the scenes sent in were dismissed for this reason. Characters weren’t going after anything (like yesterday, where our character was trying to get his girlfriend back) or reacting to anything (like Monday, where our characters had to avoid a swarm of aliens). They were just talking about other characters, or about the plot. And unless there’s something compelling that needs to be hashed out between the characters, or just a ton of conflict, talking scenes are borrrrrring. Never forget that.

Today’s script follows astronauts, Max, his love interest Amanda, Russian Sven, and the grizzled vet, Berkely. The four have just landed back on earth after being in orbit for awhile and boy, are things different. The planet’s been scorched. It doesn’t look like there’s any more water. After looking around from the safety of the ship, they spot a man sitting in this barren field, facing away from them. They leave the ship and go to him, only to find out he’s a decoy. It’s a trap. They hear something big and angry emerge out of nowhere and they start running. They get back inside the ship, only to be repeatedly rammed by whatever this is. Just as it looks like their ship is about to break, the banging stops, and a man in a cloak emerges from the shadows, beckoning them to open the door. He can help.

There were a few things I liked about this scene. First, there’s suspense. What the hell happened to the earth? Next, there’s this guy just sitting out there in the desert. Who is he? Why is he facing away from them? More suspense! They approach the guy. What’s going to happen?? We don’t know but we want to find out!

And what we find out is that he’s a decoy. They’ve been lead out here on purpose. Knowing they’re in trouble, they run back. And what I loved is that Rzwan did NOT SHOW the huge monster chasing them. We only HEARD it. This is an indication to me of a writer who knows what he’s doing. Amateur writers tend to blow their load and be completely obvious with every situation they write. They would’ve shown this monster in an instant, erasing all the mystery behind it. Because we don’t know what it is, we must imagine the monster ourselves, just like our characters. And just like our characters, our assumption is probably a lot scarier than whatever the writer could’ve come up with.

This is followed by the arrival of the man in the cloak, which creates another “mystery box” that is intriguing enough to get us to the next scene. Add all that to some really slick writing (Rzwan’s prose is lean, crisp and quite descriptive) and you have yourself a nice little scene.

Frustratingly, despite it being better than the majority of scenes that were sent in, it wasn’t perfect. The arrival of the cloaked “person” in the chair wasn’t introduced clearly enough. I’m presuming we landed here in this huge barren landscape where we can see all around us. Nobody saw anything then?? Their first look around once they’d landed produced the same result. Nothing.

Then, all of a sudden, there’s just some guy sitting in a chair? How did they miss that?? Even worse, we’re never told how far away he actually is. Is he 10 feet away? Is he 500 feet? These things matter, particularly when we’re trying to figure how this figure who’s sitting on a chair in the middle of the desert can be missed.

Remember, one clarity error in a scene can KILL that scene. Every single little thing you were trying to accomplish, from the location to the setup to the characters, can be capsized by a single clarity error. And the truth is, we can’t always catch these. In our minds, because we can see the whole thing in our head, the setting is clear as day. So of course we’re likely to under-describe. On the flip side, if we over-describe the scenario and get TOO detailed, the scene gets bogged down in text and reads like molasses.

So you have to find that balance. All you can do is ask, “Have I made all the key elements to this scene clear to my reader?” And then, of course, before you send it out officially, you get a few people to read it and see if they understood it as well.

As for the rest of the scene, I like the mystery of Max (the cloaked man who approaches at the end), but a) I’m wondering how yet another character could’ve just appeared out of nowhere in this endless barren desert, and b) When I see cloaked people in deserts (which believe it or not I’ve seen a few of in the last few weeks via script reads), I immediately think of Star Wars. And when you’re writing sci-fi, you want to avoid stuff feeling too similar to the most popular films in that genre.

So to summarize, I liked the machinations of this scene. I liked what Rzwan was doing to create anticipation and suspense. I love how he didn’t show us his monster. But some of the details needed more explaining, like how people in chairs can just appear out of nowhere. And maybe we could’ve milked that build-up a little bit more. More discussion/arguments before going out to look at Chair Guy. More description of the eerie landscape. When you have a suspenseful situation like that set up, you want to milk the suspense!

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read (just barely)

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Information (exposition) should never be the focus of the scene. It should be a secondary directive only.

What I learned 2: If you can’t come up with a creature scary enough, don’t show it! Or only show pieces of it. Let the reader imagine what it is himself. The version in his head is probably a lot more freaky!

Genre: Rom-Com

Premise: (from me – based on limited information) A young man finds his relationship threatened when the former love of his life, now a famous singer, makes an unexpected visit.

About: A couple of interesting points to make. One, this is Illi’s first screenplay. And two, it was a finalist in two New York screenwriting contests (the New York Screenplay Contest and the Screenplay Festival).

The setup: John has been dating a girl, Lucia, who has no idea that he used to date the famous singer, Verena, who’s currently in town. John actually bought the ring to propose to Verena a long time ago but never did. Lucia finds the ring and believes John is proposing to her. John tells her the truth in an inadvertently asshole-ish way, and she dumps him. So John goes to the supermarket where she works to apologize and get her back with a big surprise.

Writer: Illi Ferreira

Details: 7 pages

As I went through scene submissions, one of the most interesting things I found was which scenes people picked to send. I quickly realized that WHAT a person sent was a quick indication of where they were as a screenwriter. Some scenes were literally two pages long, bridge scenes, that had our characters moving from one place to another, discussing immediate plot points, probably the most un-dramatic moments in the entire script.

Others thought huge action scenes were the way to go. I know that’s what I reviewed yesterday, but that’s because the scene was constructed soundly and well-written. Typically, big action scenes aren’t what a script is about. A script is about the characters and what’s going on between them, whether those problems be familial, relationship-based, or work based. A good scene to pick, I think, would be something revolving around one of those relationships, that showed a clever set up, intriguing conflict, a surprise or two, wrapped in a slightly unexpected package. That’s what I was looking for. Scenes that made you think a little.

Instead I got a lot of obvious straight-forward scenes where characters were saying exactly what was on their minds (no subtext). A lot of shooting. A lot of yelling. A lot of plot-reciting. At least with today’s scene, the writer put some thought into his characters and came about their interaction in a slightly different way.

For those too tired to download the scene, it has John, our main character, show up at Lucia’s work (she’s a cashier at a grocery store) to apologize for being mean the other day. Of course, because she’s working, he has to buy something – each item a sort of “time credit” for him to continue his apology. She’s not hearing any of it though, and is trying to speed him through the line. Customers appear behind him, putting pressure on him to hurry up. Can he get her to accept his apology in time? Or will he fail and lose Lucia forever?

You remember the term “scene agitator” from my book, right? This is when you add an element to the scene that agitates your characters, that makes it more difficult for them to do… whatever it is they’re doing. Here, we see that agitator in the form of a checkout line. John cannot speak freely with Lucia because she’s at work. In order to talk to her, he must buy something like everyone else. Then, when he gets in line, he only has until the end of the sale before he has to leave.

I thought this scene would be fun to discuss because it presents the writer with a choice. That’s the thing with writing. It’s never one simple route. Often, you’re going to have tough choices, with each choice having its own pros and its cons.

So here, John gets in line and starts pleading his case to Lucia. The idea is to make things tough on John, right? We want time to be running out for his apology. So traditionally, you’d put someone behind John – preferably someone very impatient. And that’s what Illi does here. He puts an old woman behind him.

But Illi decides to go another route and pull some laughs out of the situation. In order for John to continue to talk to Lucia, he needs to keep buying things. So he keeps grabbing a new bag of chips off the rack every five seconds or so. After awhile, seeing what he’s trying to do, the woman behind him starts grabbing chips for him. She starts helping him, which is kind of funny.

In other words, there was a choice. We could go with the option that provided the most drama for the scene. Or we could add some humor. Illi opted for humor. Which is fine. But the scene did lose a little bit of that urgency as a result. If we would’ve seen an impatient businessman behind John, and every 30 seconds another impatient shopper got into line, now we’re REALLY going to feel some dramatic tension.

When you’re writing any sort of character interaction, I think you’re trying to put your characters in less-than-ideal situations to have that conversation.

Have you ever set up a plan to tell someone you liked them? And you have it all worked out perfectly how you’re going to do it? You’re going to go to their work, wait for them outside, greet them with a surprised ‘hello,’ offer up a few carefully practiced jokes, then casually ask them out to a movie? But it never goes like that does it? You wait for them outside their work. They end up being late. So it gets dark. Now you look like a stalker. A night time guard approaches you, suspicious. He asks you what you’re doing out here. You nervously tell him you’re just waiting for a friend. He doesn’t believe you, so he stands nearby and watches you. The girl finally comes out. You’re freaked out about the guard so you look nervous and jittery. She picks up on that and now she’s creeped out. Right before you get to your first joke, some guy comes out, puts his arm around the girl. “Hey, you ready?” he asks. She looks at you. “Yeah, just a second. (to you) What were you about to ask me, Joe? Something about a movie?”

Whenever you want to talk to anyone about something important, it NEVER goes how you plan for it too. And that’s really how good dialogue scenes work. Whatever was planned goes out the window because all these unexpected things should be popping up. Sure, the perfect “nothing goes wrong” scenario is wonderful for real life. But it’s boring as hell for the movies.

I liked how Illi created that imperfect scenario, which is why I liked his scene. That doesn’t mean there weren’t problems. I couldn’t put my finger on it but the scene itself felt a little clunky. There were too many action lines between the dialogue, making it difficult to just read and enjoy the scene. I thought the dialogue was okay, but not exceptional. And in rom-com spec sales, the dialogue is always really strong. So Illi still has a ways to go. But this was a solid effort for sure.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Dialogue scenes benefit immensely from a time limit. Create some reason why your characters have to get their conversation over quickly, and you’ll find that your scene instantly feels snappier, more energetic.

Okay folks. Doing something different this week. Many months back, I had people on my mailing list send me their best scenes from their current scripts. The plan was to read them all, then review the full scripts of the best scenes. Due to a couple of factors (the primary one being that I didn’t find anything that blew my socks off), I’ve changed my mind. Instead of reviewing the entire script, I’m only going to review the scenes. I realized that in all the reviewing I’ve done on this site, I rarely analyze and break down individual scenes. And obviously, with scenes being the primary building blocks of a screenplay, that’s kind of absurd! So this week, I’m going to review five scenes, and then, whichever one gets the best feedback, I’ll review the entire script. Let the fun begin!

Genre: Action/Sci-Fi

Premise: (from writer) ALIENS meets THE MATRIX as a troubled soldier leads a group of mercenaries into a hostile, alien dimension to retrieve an ancient artifact. Against his wishes, his estranged father is along for the ride and is the only one that can lead them out.

Scene setup: The writer’s setup is too elaborate to include, but basically we’re in a gigantic alien hive lit by a river of flowing lava.

Writer: Logan Haire

Details: 7 pages

Download and read the scene here.

As I started reading the scenes for Scene Week, I learned the most valuable lesson I’ve learned in a long time. Let me set the scene (heh heh). I was at a café for reasons beyond my control, and so had to read some scene submissions in a busy place with people constantly walking in and out of the door just a few feet away from me. It was Distraction Nation. Which meant I had a hard time concentrating.

So I’m trying to read page after page but something’s always happening. A click. A bang. A loud laugh. Something always caused me to jerk up, to see what was going on.

That’s when it hit me.

When you write, you have to write in such a way that the reader CAN NEVER LOOK AWAY. You have to make it IMPOSSIBLE for them to look away, no matter what kind of distraction pops up.

I remember reading a book a couple of years ago – “Before I Go To Sleep.” It was told from the perspective of a woman waking up with amnesia who was in bed with a man she didn’t recognize. She was scared, confused. She needed answers. She realized this wasn’t the “long night out, wake up the next morning” type of forgetfulness. This was a deep forgetfulness. Something bigger and more terrifying. Then, when she walked to the bathroom, when she looked in the mirror, she almost fainted. She saw someone 15 years older than herself staring back at her. Why the hell did she look like this?? The scene continued like this and even though I HAD to go to sleep because I had a big day the next day, I couldn’t stop reading! I NEEDED to figure out what had happened to this woman.

I felt the same way when I read The Disciple Program and Django Unchained. Tyler and Quentin wrote these scenes that you just COULDN’T look away from, even if you wanted to. They pulled you in and never let you go. Sadly, I can’t say a single scene I read here (out of hundreds of submissions) compelled me to keep reading. Don’t get me wrong. There were a lot of SOLID scenes. There was a lot of professional-level writing. But again, there was nothing that made me want to read the entire script.

For that reason, I think it’s best to look at this week more as a learning experience than a “These are the best!” set of posts. The truth is, I haven’t spent a lot of time breaking down scene-writing on the site. So I’ll probably learn a few things myself.

As such, even though I know it will make the comments section messy, feel free to pitch your scene (and provide a link to it) if you felt like your scene was INDEED “Must Read” worthy. If a bunch of commenters verify that, yes, your scene kicked ass, I’ll be more than happy to review it. So again, I found about 20 decent scenes that were all of similar quality, and I’m basically picking at random between them for the 5 reviews.

For those who didn’t read the Harbinger scene, it’s basically about a group of military dudes who find themselves in some sort of alien hive. As they’re walking through this thing, they see the aliens (or demons, as they’re known) skittering through the hive walls, watching them. What starts as just watching, slowly evolves into an attack, and our guys start running and shooting in a desperate bid to save themselves. They even enact a “nano second skin” that can’t be penetrated as part of their defense. But with the demons are growing in number and with our team running out of solid ground, even that may not be enough.

I chose this scene because, while it didn’t do anything mind-blowing, it was a solid action scene that kept me entertained, that I could visualize, and that I could imagine on the big screen.

The first thing that stuck out to me is something that barely ANYONE did with their scene submission, and that’s create suspense. We see the shadows of these demons running through the hive walls as our military group is walking. We know it’s only a matter of time before they come out. So we’re on edge. That anticipation is getting us all antsy, scared of WHEN they’re going to attack. That’s how you want your audience to be. All antsed up! You never want them to be relaxed.

You know when you have one of those impossible days? You have to write, work, read a friend’s script, pick up your dry cleaning, get your girlfriend a card, pay a few bills, be home for the cable installation, etc., etc.? Add to this that you woke up late. So you’re already behind on the day. Just the thought of doing all these things in such a small amount of time stresses the hell out of you. I want you to imagine that feeling. That’s the kind of feeling you want your reader to have when they’re reading your script! They have to feel like there’s so much that needs to get done and there’s no way your characters can do it.

I also like how this scene builds. It progresses. It isn’t just stagnant and one note like a lot of the scenes I read. Aliens start slinking out of the hive, bit by bit. So the threat is getting more intense. In other words, the situation is DIFFERENT from how it was one page ago. And the threat will be even worse one page later, growing again.

I also like how when the action begins, it’s told inside 1-2 line paragraphs (with an occasional 3-liner). I see a lot of bad action scripts that pile in 3-4 line paragraphs one after another during huge action scenes. If stuff is supposed to be happening fast on the screen, shouldn’t it be happening fast in the reader’s head? To do that, you have to keep the lines short and sparse.

Likewise, Logan’s prose was very clear. And you may be saying, “Shouldn’t that be a given?” The answer is yes, but it’s something I saw a LOT of writers in Scene Submissions struggle with. And here, it’s INCREDIBLY important, because we’re talking about an alien world, an alien setting, multiple characters, and a lot of action. It’s easy for a reader to get confused if a writer isn’t doing his job.

My worry here is that the scene (and concept) is too familiar. It’s a lot like a video game (Gears of War for me, and of course, Aliens on the film side), and the lava stuff reminded me of the dreadful CGI ending to Revenge of the Sith. This kind of stuff seems like it shouldn’t matter. But it does. Anyone who reads your script is going to get a little weary if it’s too similar to something else. We want to see originality, something new and different, and that’s not what I got here. When I said earlier, “None of the scenes I read propelled me to want to read the scripts,” for Harbinger, is was that “too familiar” feeling that did it in. I’ve been in this world numerous times already. So why would I want to revisit it?

With that said, I might give it 10 pages. Logan has proven he can write a scene. And for that, I have to give him props.

[ ] what the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read (barely made the cut)

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: I didn’t see this in Logan’s script, but his sparse writing reminded me of it. — Isolate character names during big action sequences to create more of a “vertical” read. A “vertical” read just means that a lot of the text is near the left side of the margin and all the action lines are sparse, allowing a reader’s eyes to fly down the page “vertically”). I don’t like to see this used just anywhere in a script. But it’s a GREAT approach to adapt for action writing. For example, instead of:

Jetson lands hard on the concrete, shaking the room. He spins his gun out of his holster and shoves it into Frank’s face. Frank stares down the barrel of the gun, half an inch from his nose.

You’d write:

JETSON

Lands hard on the concrete, shaking the room.

He spins his gun out of its holster, SHOVES it into Frank’s face.

FRANK

Stares down the barrel of the gun, half an inch from his nose.