That March Newsletter is in your inbox. If you aren’t signed up for the newsletter, e-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com and I’ll put you on the list

Since it looks like The First Horseman is running away with the First Page Showdown title, I’m going to put this post up early so that people can discuss the Oscars while it’s going on. But if you still want to vote for First Page Showdown, head on over to that post and cast your vote before midnight.

I’ll make my screenwriting predictions here. For Adapted Screenplay, there’s no contest. Conclave was excellent and leaves the other scripts in the dust. The Original Screenplay Category is tougher to call. Anora is an exceptional script in the way that it takes risks throughout yet never loses momentum. But I think voters see it more as a movie. The Brutalist also has some great writing. Any time you’re working within a longer running time, it becomes infinitely harder to keep the reader/viewer invested. And The Brutalist manages to do that. But, again, it comes off more as a directing feat than a writing feat.

Which means it’s probably going to come down to Anora versus A Real Pain. I’ve seen A Real Pain. I found it to be highly average and a bit of smoke and mirrors. It’s essentially a vehicle to let Kieran Culkin act like himself for 2 hours. I didn’t find the writing to be memorable at all. The one argument you could make for the writing is that Eisenberg “crafted” this memorable character. But, like I said, this is less writing and more an actor doing his schtick.

But will Hollywood be fooled by that, I don’t know. I hope not. Cause I’d rather have Anora win. But ya never know with this show. Sometimes I think these voters are delirious.

Okay, onto the newsletter!

NEWSLETTER SCRIPT NOTES SUPER-DEAL!

The March of Scribes Script Notes Deal is back for 2025! After reading 10,000 scripts, I’ve found that most scripts have one MAJOR issue holding them back and, for whatever reason, that issue exists in the writer’s blind spot. Let me be your shotgun passenger. I can look behind you, see what’s in that blind spot, and help you turn an average script into a great one. I am giving out FOUR half-off script notes deals to the first two state-siders who write me and then the first two writers from anywhere else in the world. Your script DOES NOT NEED TO BE READY. You can pay now and send the script in later, when you finish. E-mail me at carsonreeves1@gmail.com and we’ll get you set up with some game-changing notes.

The other week, I reviewed a script on the site called American Monsters. It was about this team of people who hunt mythical monsters on a remote ranch. What stuck out to me about that script was just how good the first act was. It really set everything up well, from the characters to the plot. However, once we got to the second act, the script slowed down a little. It wasn’t bad. But it became a bit formulaic.

Not long after that, I was reading a script from a client and the opposite happened. The first act was really messy. Character intros were in major need of an overhaul. I wasn’t really sure what the plot was going into the second act. I was losing faith in the script with every passing page. But then I got to the second act and the script came alive! It was like, all of a sudden, the writer knew exactly what he wanted to do.

Now let’s take a time machine back to a couple of months ago. I read a script that was absolutely atrocious. First act was terrible. Second act was abysmal. But somehow, some way, the writer wrote a really good third act with a hell of an ending.

For whatever reason, I was thinking about all three of these scripts one day and this brand new screenwriting revelation hit me. You have to understand, I don’t get many screenwriting revelations these days. There are only so many things one can learn! So this was a big deal.

What was my new revelation?

That the reason screenwriting is so hard is because each act requires a completely different skill set.

Let’s go through them one by one.

The first act is a technical act and therefore favors highly logical thinkers. It’s like the screenwriting equivalent of being an engineer. You have to set up the main characters and set up the problem they’re facing and set up the plot. And it’s really important to do so by certain page markers, which makes it highly mathematical.

Once you reach the second act, the technical aspects of writing become a lot more flexible. A big reason for that is that instead of having 25 pages to work with, you have 50. So, already, you don’t have to worry about cramming everything into this tiny space, which is what necessitated that mathematical approach in the first act.

The second act is also the most creative act. It’s about coming up with creative obstacles and coming up with creative plot points. You’re letting your mind roam in this act. If you do it right, this is the act where you’re going to have the most fun. Of course, for the technical thinker, this act is terrifying. It seems boundless and endless with no clear set rules to follow.

The third act is unlike either of these acts because it’s about bringing everything together. If you’re writing a thesis paper, this act is your concluding statement. And when you’re concluding anything, you’re bringing things together in your head in a way that has nothing to do with the setup or with creativity. You’re trying to land the damn plane.

Because each act requires such a unique skill set, it’s rare that you’re able to find a writer who’s good at all of them. And hence why you have so many scripts that start off strong and then dissipate. Or, to a lesser degree, start off terribly then heat up.

It’s almost like we have to become three different versions of ourselves to get a script right. The good news is, now that I’ve told you this, you can put yourself in the right mindset for each act.

When you enter that first act, you must be “Logical Guy.” You must think very carefully about each and every page and how you’re using them to set up your characters, set up your plot, place that inciting incident where it needs to be, be methodical in how you write exposition. You need to somehow convey a million things to us yet keep things moving.

Back in the late 90s, every single pro screenwriter was really good at first acts because first acts were what got scripts sold back then. If you could set up an amazing movie with your first act, studios bought it because they were afraid the studio down the street, who was reading the screenplay at the same time they were, was going to buy it before they did. Better to buy after a great first act than risk losing the script cause you read the whole thing. Over time, however, since that system died down, writers have gotten pretty bad at first acts.

Once you get to your second act, you must become “Creative Guy.” The second act favors writers with strong imaginations who take bold creative chances and who, frankly, are good at entertaining people. A good example of a writer who thrives in his second acts is Bong Joon-ho. He’s got such a wacky sensibility that he comes up with these weird ideas, like the secret basement man in the Parasite house.

Quentin Tarantino is another writer who thrives in his second acts because all he cares about is entertaining people. So he just has fun with his scenes. He’ll throw you in the middle of the Manson farm, in a cafe in Germany circa 1942, or in a basement with a gimp. He defines the type of creativity the second act favors.

Of course, you still need structure to your second act. You still need to build towards the third act with your scenes and create a nice midpoint that ups the stakes. You need to know how to create obstacles, challenge your characters’ flaws, and consistently inject conflict into the story. But, overall, this act is about entertaining people and you should have fun with it.

The third act is a unique beast. To conquer it, you need to be “Time-Traveler Guy.” Let me explain. Your final act isn’t just about paying off what you’ve set up. It’s about trying to look for ways to make your ending amazing and, often, that means looking back into your script (time-traveling) to see if your setups can be improved to create an even better payoff.

The example I love to use for this is, ironically, Back to the Future. Originally, the time machine in that movie was a static refrigerator in a junkyard. Now, had screenwriters Zemeckis and Gale simply paid that off in their third act, we would’ve gotten a much weaker movie. But by going back in time (no pun intended) to their earlier scenes and challenging that setup, they eventually realized that a more active time machine would work better. They then had to time travel through the rest of the script to adjust for this new setup, but boy did it make a gigantic difference with the ending, where it became one of the time five endings in movie history.

Maybe a better way to put it is to say that, in order to conquer the third act, you have to think three-dimensionally. You can’t just rote-ly connect all the dots you set up beforehand. There are potentially magical revelations, like the Delorean rushing to the clock tower as the lightning strikes, in that third act if you’re thinking three-dimensionally.

Okay, now that you know all this, it’s time to get out there and write your next script. Because we have a script showdown coming up in June! I’m going to help you get ready for that, each month, with a new showdown. I’ll share the latest of those showdowns with you in a second. But first, we have to talk about Bond.

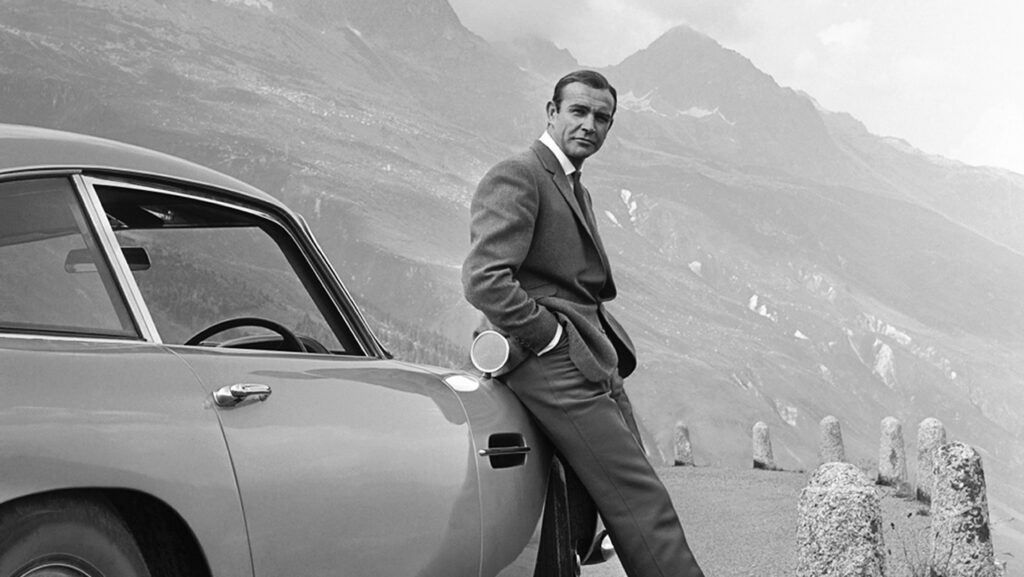

JAMES BOND

There was a seismic move in Hollywood this weekend. It occurred when the Broccolis finally let go of creative control of the Bond franchise, handing it over to Amazon. The whole thing was kind of weird because Amazon already bought the franchise when they bought MGM. But I guess the Broccolis retained creative control of the franchise as part of the deal. Well, over the past three years since that deal was made, the Broccolis haven’t done jack diddly with the Bond franchise and Amazon had had enough. So they dished out another billion bucks so that they could do whatever they wanted with 007.

A lot of people are calling it a tragedy. And, to a certain extent, they’re right. The Broccolis are one of the few people who think you make a movie once you have a good idea. Not the other way around. And the pitches they were getting weren’t very good. So they rejected them.

To be fair, pitching a Bond film must be hard. I mean, how many different ways can you say, “Bond goes to this continent. Then he goes to that continent!” It’s the kind of franchise that differentiates itself in a) the actor who plays Bond, and b) the direction. As scripts, all these Bond movies, much like the Mission Impossible movies, feel the same to me.

But that opinion may be because I’m not a Bond expert. And, for that reason, I decided to bring in Scriptshadow’s resident Bond expert, Mr. Scott Crawford, to give me an insider’s take on what’s gone on here and what it all means.

So, here’s Scott!

Amazon has paid over $1 billion to take creative control of the James Bond movie franchise from producers Michael G. Wilson and Barbara Broccoli. The world’s longest-running movie franchise, which for almost 63 years has been a London-based, independent, family-run affair, has been taken over by the world’s second largest company. From Dr. No in 1962 to No Time to Die in 2021, one name has been synonymous with the franchise: Broccoli.

It was British-based American producer Harold R. “Harry” Saltzman who in 1961 gave Fleming $50,000 for a six-month option on James Bond. Just as the option was about to expire, Saltzman teamed up with another British-based American producer Albert R. “Cubby” Broccoli and secured the backing of David Picker at United Artists (UA). Broccoli and Saltzman formed a company called Eon to produce the movies.

UA, a studio founded in 1919 by Charlie Chaplin and friends, took a hands-off approach to making films. They agreed to finance and distribute the Bond films while Eon would produce. Profits would be split 50/50, Eon’s share rising to 60% and then 75% as the films remained profitable.

The formula was simple but effective: make the Bond films relatively cheaply in England, at Pinewood Studios just outside London, and – as the budgets got bigger – at locations around the world. Casting a relatively unknown actor – Sean Connery – as Bond rather than a star like Cary Grant or David Niven saved them money they could use to build huge sets.

By the mid-70s, Saltzman’s outside business activities had got him into huge financial debt and in 1975 he sold his half of Eon to UA for $36 million. UA now owned half of Eon but agreed that Broccoli – who would now produce the series alone – would retain creative control.

Broccoli’s stepson, Michael G. Wilson, a lawyer who had previously been an assistant on Goldfinger and legal advisor on The Spy Who Loved Me, became an executive producer on Moonraker, For Your Eyes Only and Octopussy and a full producer on A View to a Kill in 1985. He would be a producer on every Bond movie after that. In addition, Wilson co-wrote all the screenplays for the five Bond films released in the 1980s and continued to contribute many story ideas going forward. Cubby remained the man in charge, but from 1981 onwards, day-to-day production was handled by Wilson.

Money problems at MGM led to multiple delays on productions, the longest of which was six years between Licence to Kill in 1989 and GoldenEye in 1995. During that time, producer Joel Silver tried to buy Bond but was told it would cost $150 million to get the rights.

MGM/UA’s shaky finances eventually led to the announcement of its sale to Amazon in May 2021, five months before the release of No Time to Die, for $8.45 billion. The sale included half of Eon since MGM owned half of Eon after buying UA which had been sold half of Eon. Which many speculated to be the reason why Amazon paid (overpaid) such a large sum.

But Wilson and Broccoli retained creative control, per their contract.

Amazon MGM became almost immediately impatient, having paid over eight billion dollars, and pushed for a James Bond TV show, an idea which Barbara rejected. Another Amazon executive said they didn’t think Bond was a “hero” and when Amazon MGM head Jennifer Salke referred to Bond as “content,” that seems to have been the the tipping point.

Wilson had announced his retirement from Bond after No Time to Die. Barbara didn’t want to produce the series alone, or with a new producer, and so she sold creative control to Amazon for $1 billion+ to let them produce the films. Let’s see how easy they think it is.

Many people have tried to copy Bond, including 100s of Italian “Eurospy” movies, as well as two unofficial Bond films: a 1966 comedy based on Casino Royale and a 1983 remake of Thunderball starring Sean Connery called Never Say Never Again. Both cost a fortune, more than any Eon film to that point, and neither was as successful.

It’s not as easy as people think it is.

With Amazon given full creative control, the chances of seeing another James Bond film within the next few years have increased, but the worry is that this will be at the cost of the scrutiny that the Broccolis brought to the franchise. The push to make the films for less money, use CGI over practical effects and make Bond more American (Bond movies usually only make around a quarter or a fifth of their money in the US which affects profits) can only result in a more substandard product.

The other fear is that Amazon will push for a Bond TV show. Lots of TV shows. A TV show for every other character… a Miss Moneypenny show… the Q show… a Felix Leiter show… diluting (a word which keeps coming up) the franchise just as it did for Marvel and Star Wars.

Quantity over quality. Bond is too big for TV; he belongs on the big screen.

Personally, I don’t think Amazon will make MULTIPLE TV shows (a la Star Wars and Marvel) because the backlash against that has been so immediate. I think they might do one just to exploit the rights more, but it will be a movie next, first and foremost.

The next thing Amazon will have to do is find a new producer to “run” Bond. That producer will have to find a new Bond (good luck with that)… and do all the rest, probably without the support of the outgoing producers.

To cap it all off, last year Wilson & Broccoli were awarded the Irving G. Thalberg Oscar, a lifetime achievement award for producers, at the governor’s ball. This is a VERY prestigious award; it isn’t handed out every year. Among previous recipients of the award, back in 1982 when it was still shown on TV as part of the main ceremony… was Albert R. “Cubby” Broccoli. His stepfather. Her father.

That’s how respected they are in Hollywood: they gave them an Oscar.

And now… they’re out.

Yeah, I agree with Scott that Marvel and Star Wars have established the protocol for how NOT to treat a franchise re: all these TV shows. But here’s the problem. Amazon has never had a franchise like this before. They paid kabillions for Tolkien’s work but that was for the crappy Tolkien books no one read. Now they’ve got James Bond. JAMES FREAKING BOND. Do you think they’re only going to produce one movie every five years when they have JAMES FREAKING BOND? Helllllllllllllllll no.

So, as someone in the comments said, we will get shows for 001, 002, 003, all the way up to 009. Will that destroy the franchise? Here’s the thing. Bond has a unique problem specific to it and only it. It is ONE DUDE. Just one guy. So, if you come up with the perfect casting, similar to Tom Holland becoming Spider-Man, those shows won’t matter. People will joyfully come to see new Bond movies. Especially because they’ll now have a new one every year. ;)

And the March Showdown is… SCENE SHOWDOWN

That’s right. January was Logline Showdown so we could find you a script to write. February was First Page Showdown so we could get you started on your script journey. March is Scene Showdown. Which means, that’s right, you’re going to enter an entire scene. The only rule is that the scene must be five pages or less. What I’m looking for here is the ability to tell a story within a scene. Scenes are, essentially, mini-scripts. So if you can tell a strong story within a scene, that tells me you know how to structure your larger story, aka your script. Your entry doesn’t have to be the first scene of your script. It can be any scene. And because some scenes are going to need context, I will give you 50 words MAX to set up your scene if need be. Okay, can’t wait to see what you have in store.

What: Scene Showdown

Rules: Scene must be 5 pages or less

When: Friday, March 28

Deadline: Thursday, March 27, 10pm Pacific Time

Submit: Script title, Genre, 50 words setting up the scene (optional), pdf of the scene

Where: carsonreeves3@gmail.com

AROUND TOWN

Andor Season 2 Trailer – At this point, I think Disney’s trolling. I know a small group of Star Wars faithful who champion this show. But I never liked it because the creator, who openly states he dislikes Star Wars, has no interest in making a Star Wars show. He wants to make an adult drama about living under an oppressive system. He’ll begrudgingly add Star Wars touchstones if need be. But he doesn’t care about the universe, which is clear in every frame of the story. This trailer for the second season could not be more indicative of that. Our story, which takes place a long time ago in a galaxy far far away, is playing a 2025 rock song. Could you bastardize Star Wars any more?? I just want Kathleen Kennedy to go away. She doesn’t understand this franchise and keeps missing the tonal bullseye. It’s either too goofy or too serious. Neither is Star Wars.

Havoc Trailer – I mean, C’mon. This looks absolutely badass. And there’s actually a screenwriting lesson to learn here. Havoc is an action movie. It’s a movie where people shoot a lot of guns at other people. If you are going to make an action movie where people shoot a lot of guns, then make sure every scene that has action and every scene that has guns is amazing at the action and gunplay!!! Nobody will care if this movie isn’t funny. Nobody will care if the character development sucks. Nobody will care about clever plot twists. All they’ll the care about is the action and the guns. Same deal when you write scripts. If you write a comedy, 90% of audience satisfaction will be due to whether they laugh or not. If you write a horror film, all I care about is that your scares are first-rate. If you write a Hitchcockian thriller, you better be amaaaaaazzzzing at writing suspense. Havoc knows what it is and its writer and director knew to prioritize that. Which is exactly why I’ll watch this the day it comes out.

87 North Heist Action Thriller – We’ve got a big heist project that sold to Amazon. 87 North, David Leitch’s company, is producing along with Imagine. Leitch has made a lot of middling movies since he co-directed John Wick. Atomic Blonde, Hobbs and Shaw, Bullet Train, and most recently, the frame-by-frame flop known as The Fall Guy. Lavish production value and star power slathered on a script so vanilla, they’re naming a Starbucks latte after it. But I understand why Leitch believes he doesn’t need good screenplays. He broke out with John Wick. That John Wick script was laughed at all over town. John Wick was never seen as a script success. It was seen as a directing success that became great in spite of its script. So why would Lietch think you have to work hard on a screenplay? Which is why he’s hiring some guy named Mark Bianculli to write this. He of the vaunted TV series, Lincoln Rhyme: Hunt for the Bone Collector, whatever that is. The pitch for this script is that a group of bank robbers use social media to document their heists. So, we’re taking an age-old story trope – bank heists – and we’re modernizing it. But if they don’t have a writer who knows how to dramatize scenes so that the audience actually stays invested, Leitch is in trouble again. With that said, rumor on the street is that Bianculli and Imagine have been developing this script for a decade. A DECADE! So, maybe that’s why 87North is teaming UP with Imagine. Cause Leitch is finally realizing, after Fall Guy, that the script is important. I don’t have a ton of confidence in that theory. But we’ll see.

UFO Conspiracy Thriller – One of the biiiiiiiig scripts that’s been getting the town excited is Zach Baylin’s new UFO conspiracy thriller, which is being pitched as “All The President’s Men meets UFOs.” Baylin wrote King Richard, about Serena and Venus’s crazy dad. He wrote Creed 3. And he most recently wrote the 70s crime thriller, The Order, about big bad white supremacists. I think the concept here is good. Most writers who write in this space focus on the aliens. This sounds like it focuses on the conspiracy aspect and whether there even are aliens. This conversation has been pretty intense in the real world over the last few years. A lot of people, such as myself, think some level of UFO disclosure from the government is imminent. So, why not treat the subject with an adult lens instead of the kiddie lens it’s usually explored through? That’s the main thing we have to remember when we come up with a concept. Every subject matter has been done to death in Hollywood. But not every ANGLE has been done. And this is the answer to the age old question, “What does Hollywood mean when they say they want something ‘the same but different?’” The answer is they want the same subject matter (aliens) but a different angle (explore them through a serious investigation).

Fantastic Four Trailer – This was a head-scratcher. Fantastic Four is the first film in the next phase of Marvel’s storied franchise. Therefore, we should see a clear correction from all the mistakes they made in the last phase. Yet they started off doubling down on the biggest mistake of all – the multiverse. This Fantastic Four movie takes place in some 60s futuristic universe. Kevin, buddy, Carson here from Scriptshadow. Got a “what I learned” for you. If a movie takes place in a parallel world that has nothing to do with the one we, the audience, live on, that means there are zero stakes attached to anything that happens. The whole planet could blow up and it wouldn’t matter at all. You’re going to start your new phase with that? The multiverse is the worst case of toothpaste leaving the tube that I’ve ever seen. Cause if there’s anything that needs to be put back into the tube, it’s the multiverse. But now you’re fucked. You opened that door and you’re fucked. I also found it odd that the movie trailer featured Ebon Moss-Bachrach, known for playing Richie in The Bear, in character as The Thing, discussing cooking. Most of the audience for The Fantastic Four—probably 90%—won’t know what The Bear is. Even fewer will recognize that The Thing is played by Ebon Moss-Bachrach, the same actor who portrays Richie. Prioritizing such a niche Easter egg moment in a trailer tasked with selling the next phase of Marvel feels like the largest of large miscalculations. Why not prioritize… oh, I don’t know… crafting a good movie concept!? I heard someone say they thought this might make a billion dollars this summer? I think it’s going to play like every other non Deadpool non Spider-Man superhero movie. 80 million dollar opening and a plunge off a cliff.

SCREENPLAY REVIEW – BLUE FALCON

Genre: Action Comedy

Premise: When a retired CIA agent learns that his estranged son is marrying the daughter of his nemesis, he must travel to a destination wedding to kill him.

About: Sony purchased this script with Eddie Murphy attached to star. Screenwriter Chad St. John has been around for almost 15 years. His biggest credit would be London Has Fallen.

Writer: Chad St. John

Details: 102 pages

I remember Chad St. John! He used to sell specs consistently during the early days of Scriptshadow. It’s good to see him back. Although I’m sure he’d say, “Yo, Carson. I never left!” Let’s see what old Chad’s been up to lately.

60-something Joe Hayes is a semi-retired CIA agent who isn’t doing a whole lot with his life. His one regret is that he spent so much time on his work that he was a nonexistent father to his son, Chuck. He really wishes he could fix that relationship.

Joe hangs out with his other retired CIA buddy, Sugar. But their hang-out seshes aren’t going to last much longer since Sugar is almost dead. One of their favorite topics is discussing the disappearance of their former co-worker, Vick Arbaca. Sugar and Joe HATE Vick because he screwed the CIA over in order to secure the bag.

Joe is shocked when his son invites him to his destination wedding. Joe sees it as an opportunity to finally fix their relationsthip. However, when he gets there, he finds out that the woman Chuck is marrying is the daughter of… you guessed it… Vick! And Vick, who these days is richer than Bill Gates, is there too!

Joe then gets some terrible news. Sugar is dead. But his daughter, Sharon, is here. And she says that she’s more than happy to help Joe finally kill his nemesis (before Vick kills him). The two play a couple of deadly pranks on each other until they’re ruffied on Vick’s yacht by a bunch of college kids.

They wake up to learn that this ruffie business may be worse than originally thought. It turns out that the world’s worst bad guys, people who Joe and Vick used to make miserable, have been alerted to their position and are coming to kill them. This forces the two to team up. But what they eventually learn is that someone close by is orchestrating their demise.

I mean if they’ve got DeVito, Schwarzenegger has to be Sugar, right?

The first thing I’m going to tell you about this script is from a MARKETING perspective. Not a screenwriting perspective.

Action-Comedies sell!

Comedies may not sell. But action-comedies do. So, if you’re thinking about writing a comedy, just add some action to it. Or include lots of guns!

Now, what about the concept?

The concept here is okay. I love the enemies-who-are-forced-to-work-together trope more than anybody. So I was all for it here. My only issue with this specific pairing is that Joe and Vick were both CIA agents. So how are they enemies exactly? The script jumps a lot of rope and flips through a lot of hoops in order to explain that and I was never convinced. Vick sold CIA secrets or something? That’s why he’s a villain? Okay. I guess? But the pairing didn’t have nearly the same impact as it would’ve if Vick had been an actual villain.

And I say that for a reason that extends into the art of screenwriting itself. As screenwriters, we are constantly wrestling with our stories in order to make them feel as natural as possible. But, at times, we want to make the script go a certain way that’s a little artificial and that’s when we bring out our big writing pen and start manipulating reality in order to get what we want. Chad St. John wanted these two to be enemies but they both worked for the same side. So he wrote in a bunch of mumbo-jumbo with his big writing pen to make that as believable as possible.

Granted, comedy allows for a lot more leniency in this area. But you still have to be careful because the Joe-Vick relationship is a pillar in the script. It’s not like a tiny subplot relegated to 6 pages. So, it’s important that it’s believable, since it will affect every aspect of the story. And it wasn’t believable.

Was the script funny?

I didn’t laugh. Then again, I rarely laugh while reading scripts. I judge comedies on a less rigorous scale. Was the comedy so bad that I became angry? That happens quite a bit. Was the comedy uninspired? That’s fairly common. Was it neutral? Getting better. Did it make me smile multiple times? That’s good. And did it occasionally make me chuckle? That’s usually the high mark for a comedy script with me.

This one was somewhere between neutral and smiling.

Probably the best running joke was Sharon, Sugar’s “daughter.” She’s this wanna-be agent who’s clumsy and clueless. Her continued screw-ups were funny.

[insert page]

It may be hard to impress me with a comedy script but I can tell you how to do it. Because my journey to creating Scriptshadow started with reading a comedy script. It was called The Hangover and I absolutely loved it. It was hilarious.

Why was it hilarious? Were the writers just funnier than Chad St. John? I don’t know if they were, to be honest. But what I can tell you is that the concept for The Hangover was a million times better than this.

You see, the thing with comedy concepts is that you need something to generate consistently funny scenarios. If your concept sets up a familiar scenario, you’re going to be writing a bunch of familiar comedy scenes. But if your concept is unique, like The Hangover, you’re going to be writing a bunch of brand new comedy scenarios that you don’t even have to try to create. Cause they’re built into the concept.

Hasn’t Adam Sandler’s company already made three island movies with secret agents? We’ve seen this before. And not that long ago. So, it just feels too familiar to celebrate. Which is why it’s not recommendable for me.

Script link: Blue Falcon

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[x] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: I’m now an official fan of suggesting actors in comedy scripts. I would’ve read the part of Vick totally differently had Chad not suggested we think of Danny DeVito for the role. It instantly clarified the character and, as a result, it was one of the most effective parts of the script. Cause Danny DeVito has a very specific delivery. He can play the jerk (as he does in Always Sunny) and yet you always like him. So don’t be afraid to cast actors for your roles in a comedy script.

I want to thank everybody for sending their first pages in. It was fun reading through all of them. For me, it’s always a reminder of how difficult it is to write something that stands out. Due to the fact that these pages are pitted against other pages within seconds, it’s much easier to compare their quality than it is when you’re reading a new first page every day or two.

The truth is, there weren’t a lot of bad pages. I can count the number of “bad” pages I read on two hands. The real problem is that there were a lot of average pages. Pages that did the job but didn’t grab me or stand out in any way. For example, there were a lot of pages where we start on a mundane situation and then, at the end of the page, there’s a big explosion, or a crash, or a murder.

And, sure, that’s better than a page of aimlessness. But it’s still really easy to write a page like that. I was looking for pages that were written extremely well or surprised me in some way or set up a compelling dramatic scenario or displayed an interesting voice.

Just writing an average page then saying, KABOOM! At the end isn’t going to cut it. Even the writers who did what I said to do – which is drop us into an active scenario – a lot of you dropped us into an active scenario… that was predictable. Or cliched.

For example, I got a lot of scripts that started with people running in the woods. And either someone was after them or they were after someone. Yeah, technically, something is “happening” in these scenes. But it’s such obvious stuff that’s happening. So it didn’t stand out.

Below are the pages that stood out to me. And, if you’ve never participated in a showdown before, this is how it works. Read the five pages, identify the one you like the most, and vote for it with a comment (down in the comment section). You have until 10:00pm Pacific Time Sunday night. I review the page with the most votes on Monday.

Can’t wait to see what you guys think of these pages.

Good luck to everyone!

Title: The First Horseman

Genre: Thriller

Title: Airlock

Genre: Science Fiction/Drama

Title: Unmatched

Genre: Rom-Com/Fantasy

Title: In The Scrape

Genre: Coming-of-Age Thriller

Title: Seth and Jillian Destroy the World

Genre: Sci-Fi/Comedy

Between reading all the first page entries and putting together the March Newsletter, I have zero extra time to read a script and post a review. So today is simply a reminder that in 48 hours from when this post goes up, your first pages are due. Keep sending them in!

What: First Page Showdown

When: Friday, February 28

Deadline: Thursday, February 27, 10pm Pacific Time

Submit: A script title, a genre, and your first page

Where: carsonreeves3@gmail.com

Is this the most f’d up story of the year?

Genre: Horror

Premise: Back in 1989, a family receives an eerie visitor named Tommy Taffy, who sets up shop in the house, becoming a third parent, and torturing them in a way that only Tommy can.

About: We’ve got another big short story sale from Reddit’s Creepypasta subreddit, one of the most popular horror forums around. You can read the short story yourself here.

Writer: Elias Witherow

Details: 5000 words (about 1/4 of a screenplay)

Matt Smith for Tommy?

Matt Smith for Tommy?

No. Horror short story sales are not over.

Remember, horror is the most bankable genre in Hollywood. So it’s the one that everyone tries to figure out. And they can’t. It’s still a genre where some movies hit and others crash and burn.

A big reason for that is that there’s way less IP in horror than in other genres. You’ve got Stephen King, of course. But great horror movies (Talk to Me, It Follows, Heretic, Quiet Place, Terrifier) constantly come out of nowhere.

The thing is, Hollywood is so uncomfortable with that, that they’ll do anything if it provides even a little bit of IP. Enter Creepypasta. Some of these stories have been beloved by hundreds of thousands of people. That’s enough for Hollywood to adapt.

Hence, The Third Parent sale.

Let’s see if it lives up to the hype.

It’s 1989. 6 year old Matt is chilling with his family in their suburban home. There’s Spence, the dad. There’s Megan, the mom. And there’s Stephanie, Matt’s 5 year old sister. There’s a knock on the door. Spence goes to open it. And there’s this… man, standing there. Or some version of a man. Here’s how he’s described.

He was about six foot and had a shock of golden hair cut tight along his scalp. He wore khaki shorts and a white T-shirt that said “HI!” in red cartoon font.

But that wasn’t what caught my eye. It was his skin…it was completely devoid of pores, a perfectly smooth, creamy texture that looked almost like soft plastic. His face was a pool of gentle pink, his mouth a cheerful cut along his cheeks revealing a white strip of teeth…but they weren’t teeth. It was just a smooth, edgeless row, like he had a mouth guard on. His nose was just a slight rise out of his face, like a doll, void of nostrils.

And his eyes…

His eyes were twin puddles of sparkling blue, shining out at us from his flawless, eerie face. They were wide, like he was in a constant state of surprise, and they shifted around the room to look at us in quick, jarring motion.

Matt is both bewildered and baffled by this man’s entry into their home. But his confusion is just getting started. The father is terrified of this thing but simply says that Tommy will now start living with them.

Even though Matt knows something is very off about Tommy, the first real example that this is going to be bad is when Tommy takes Megan into the basement and, for the rest of the night, we hear the most horrifying screams that humanity has ever experienced.

You’d think that Spence would fight back but he doesn’t. He doesn’t even fight back when Tommy takes Stephanie into her room and we hear the exact same screams of horror all night.

Matt finally confronts his dad about why he doesn’t fight back. It turns out that Tommy Taffy lived in his hometown growing up and was present in every single home in the town. They chopped him up. They burned him to death. It didn’t matter. He always came back. And when he did, he punished people with an iron fist.

Poor Matt gets his own dose of Tommy time after finding his first Playboy Magazine. Afterwards, Matt asks his dad how much longer they have to endure this. “Three years,” he says. Tommy always stays for five years total. Sure enough, three years later, Tommy leaves and never comes back. The end.

Is it true what people on Reddit have been saying about this story? That it’s the most f’d up story of the year?

I would have to say…. Yes.

But just how f’d up it is depends on whether you give this story the benefit of the doubt. Is it just a shocking skin deep tale? Or is it trying to say something deeper? If it’s trying to say something deeper, it’s actually quite affecting. But I’m not convinced that’s the case. If I had to guess, I would say that the writer just thought, “How can I write the most messed up story ever and really shock people?”

And you know what? That’s not the worst strategy for a writer. With every project that a writer writes, the ultimate goal is to stand out from the pack. The way you do that is to pick a lane and be faster in that lane than everyone else.

So, if you write something that’s dialogue-centric, your dialogue has to stand above the rest. If you’re writing a thriller, you have to have thrills that stand above the rest. And if you’re writing something to shock people, you have to be more shocking than the rest.

And there’s a lane open for shock-writing right now. For the last 7-8 years, everyone has been avoiding offending people. So the writing has been very careful. Even the stuff that’s been daring has only been daring on one side. Therefore, there’s been this entire mini-generation who hasn’t been offended about certain things.

Enter The Third Parent.

Now, this isn’t total shlock. There is some thought put into this. For instance, there’s a strong core of irony built into the concept. Normally, when you have some evil person doing evil things, they look evil. They’re dirty and smelly and unkempt. When you do that, you’re being on-the-nose.

Tommy is the opposite of that. He’s clean. He’s perfect. He smiles and laughs all the time. That kind of person isn’t supposed to be scary. You’re supposed to trust that kind of person.

Another thing this writer did well was he created a character that wasn’t like any other character we’ve seen. He has clown-like qualities. But he’s not a clown. He’s this weird hybrid of a clown and a full-sized doll.

However, beyond that, this becomes pretty basic. This doll thing rapes three of the four family members in the worst way imaginable. It’s unsettling but this kind of thing works in short story form.

My question is, can it work in feature form? I’m not sure it can. I’m not sure you can have some doll clown thing hanging out and raping children for 2 hours. People are going to be beyond uncomfortable. So they have to make a choice on whether to stop the sexual abuse BEFORE it happens. The story focuses more on the THREAT of that abuse rather than the actuality of it. Of course, if you do that, you take away the one thing about your story that stands out.

What will help is to make the family more active. One thing you definitely can’t do in a movie is have a family that does nothing – that just allows this to happen to them. In this story, that’s kind of what makes it terrifying. They have no choice. But in a movie, the audience will not forgive characters who do nothing. At a certain point, the characters need to attack.

Regarding my earlier statement of, is this surface level or does it go deeper? Here’s my take on the “deeper” storyline. You guys can let me know if I’m off-base. I believe what the writer MAY have been trying to say is that every family has secrets. Every family has abuse. There may not be a physical Tommy Taffy. But metaphorically, there’s always a Tommy Taffy.

Because part of the story is about how they don’t do anything about it. They don’t go to the cops. They don’t bring in the military to nuke the dude. The families are encouraged to keep Tommy Taffy a secret.

If that’s the metaphor, it’s a good one. But, again, this could still be shock shlock. What do you think?

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: One of the harder things to achieve in horror is creating a truly terrifying horror character. Someone who REALLY scares audiences. Most horror characters I read are lame. This horror character definitely stands out. So, it’s a good idea, when writing horror, to spend that extra time creating the scariest most original horror villain you’re capable of coming up with.

I remember a few years ago when they leaked some information about how Brave New World was going to have a dozen hulks. And I said, “Hell yeah!” I want me a dozen hulks. Hulks are awesome.

But I guess making hulks is one of the most expensive things in the Marvel computer-generated world. So they only gave us one hulk. And now Brave New World has fallen to under 30 million dollars for its second weekend box office take. Which means it’s probably making less than 500 million total throughout the world.

That number is relevant because the benchmark for Marvel success is a billion dollars worldwide. So, if you’re only making half that, that’s a problem. It’s a problem for the movie and a problem for the franchise as a whole.

But let’s get back to those hulks for a second. If this movie had 12 hulks, would I have gone? I would’ve. Seriously, that would’ve made the difference. Because when I go see a Marvel movie, I want something bigger and badder than the last Marvel movie. And the last Marvel movies have given me three Spider-Mans and the iconic pairing of Deadpool and Wolverine.

You did this, Marvel. You raised my expectations. So when you only give me a subpar superhero and one hulk, no, I’m not coming to your movie. You were the face of raising the bar. Every movie either released a new superhero we wanted to see or gave us something bigger. Brave New World does neither.

So they’re going to have to figure that out. They’re close to having to pick their Avengers lineup and I don’t know if there’s anyone to pick. We’re at risk of She-Hulk making the team. If I were them, I would pay Ryan Reynolds, Hugh Jackman, and Tom Holland each a billion dollars and make them the leaders of the team.

From superheroes to super screenwriting, we are in Week 2 of The White Lotus and I’m hooked. It’s a darker hotel than usual but I’m here for it. I loved the second episode.

What’s funny, though, is that the excellence of the writing, here, is so nuanced that it’s hard to explain why it works so well. Because someone said last week, “I’m surprised you like this show, Carson, considering it goes against everything you preach on the site.”

I sort of understand what he’s saying. He’s saying that my screenwriting template for success is GSU (goals, stakes, and urgency) and really great structure. White Lotus doesn’t really use either of those things. Or, I should say, when it does, it does so in less obvious ways.

But, the reason that I love White Lotus despite it not having GSU and despite a less-than-obvious plot, is that it aces the other half of screenwriting, which is building interesting characters and creating interesting relationship dynamics.

Because it’s perfectly possible to write a good scene that doesn’t have GSU. The way you do it is you create conflict. If you can create an interesting line of conflict in a scene, the reader will be hooked by the desire to see resolution to that conflict.

Think about it. If I put two characters at a table and had them talk about their days, and each of their days were mildly entertaining. Each of them laughed at each other’s summary. If I wrote that scene, that’s not going to be a very good scene. Seeing two people remember and agree has no drama to it.

But, if one of those characters just found out that his 100 million dollar company back home is about to fall apart and there’s a good chance that when he gets back, he’ll be sent to prison. And, also, if that character (in this case, the father) goes to talk to his family and they’re all having fun and trying to include him in that fun, but his mind is somewhere else entirely? Now we have a scene!

Because we have conflict. We have an unresolved issue – in this case, with one of the main characters – and that means that, until that issue is resolved, he’s (the dad) going to bring conflict into every scene he’s in. That’s drama.

That’s a somewhat complex version of conflict but Mike White isn’t above using simple forms of conflict to create drama in a scene. In one scene, for example, the three 40-something girl friends are passing our weirdo family at the breakfast table and one of the friends realizes that she’s met the mother before.

So she stops at the table and says to her, “We know each other.” And she pitches this whole weekend that they shared on a mutual friend’s baby shower. In the scene, the mother just stares at the woman. She gives her nothing. Which forces the friend to try harder. She explains that they spent so much time together and that she’s still in touch with the baby shower mom. Which only results in the mother acting less interested.

It’s a simple scene. One person wants to connect. The other person doesn’t. But it’s effective. You watch that scene and you feel the cringe for the friend. That’s all conflict. Something is out of balance and we watch in hopes of it coming in balance.

That “out of balance” formula can extend to positive feelings as well. One of the oldest TV writing tricks in the book is putting two characters around each other who are not together – but who we (the audience) want to see get together.

If you write a TV show and you don’t have that storyline in your show somewhere, you’re doing it wrong. Cause it’s such a reliable storyline. You have so much time to fill in a show, you can’t afford not to put it in there because audiences eat these storylines up. Ross and Rachel. Jim and Pam. Mulder and Scully.

Here, we have these two workers at the hotel. The guy, a guard, is clearly in love with the girl. But she seems like she’s more on the fence. Boy do I want him to get her. I want them to end up together. That “will they or won’t they” tug of war that takes place in every scene they’re in? That’s conflict.

It’s also how you keep a show going. You have to create multiple unresolved dangling carrots that viewers have to keep watching in order to eat.

So, if the formula for success is that easy, why do so many shows fail? Because there’s an essential ingredient to the dangling carrots that, if not met, the carrots become rotten.

WE HAVE TO GIVE A SHIT ABOUT THE CHARACTERS.

That’s what Mike White does so well. He makes you care about these people first. THEN he starts weaving in these plot elements, such as the dad’s company falling apart, that create these fresh carrots we want to sink our teeth into.

What happens with bad writers is that they create thinner characters than White. They don’t establish the characters well. They don’t make it clear what each character’s flaw is. They create weak character personalities. They create uninspired seen-it-all-before relationships between the characters that feel stale the second they’re introduced.

Therefore, when they try and dangle carrots, we don’t care. Cause we don’t even care about the donkey walking the carrot.

I continue to be amazed by Mike White. I think he’s a genius. I was worried that he couldn’t pull off the three-peat. But so far, he’s pulling it off with flying colors. Mighty impressive considering his last name is White.