I’ve watched four of the six episodes of the recently released seventh season of Black Mirror and, like all Black Mirror seasons, it’s a love-hate relationship. I don’t think I’ve watched something I’ve hated more than the first episode. In that one, a wife, Amanda, gets a traumatic brain injury and they digitally replace her brain under the condition that it be hooked up to a server that cost 300 dollars a month.

Everything’s great at first but then this service starts inserting ads (Amanda will randomly recite a commercial ad out of nowhere) and the only way to stop hearing them is to upgrade to the higher tier, at $800 a month. And then it keeps going up from there.

It’s not the worst idea in the world but the contrast between the marriage, which is played completely straight, and the service, which is played like it takes place in the Monty Python universe, is so jarring that nothing ever feels right. And the actors, Rashida Jones and Chris O’Dowd, who play the husband and wife, are beyond nauseating. If you had told me that the over-under for how many times two people could proclaim their love for one another going into this show was 500, I never would’ve thought it would hit the over. But they did! They’re trying sooooooooo hard to make you love them and all it does is push us further away. And Rashida Jones may be the single most boring actress who’s ever graced the screen. I absolutely hated this episode.

The next episode had zero pretense, zero satire. It was trashy. It was dramatic. And I loved it! This girl who works at a Bon Appetite like food company is thrown into disarray when a weird girl from her former high school starts working there. Soon, our heroine starts making mistakes that she’s never made before and suspects that her new coworker is responsible. But she can’t prove it. So she goes to extreme measures to take her down.

What I liked about this episode was that it proves you don’t need a ton to write a strong story. You really only need a good starting point (a solid premise) and some conflict. The heavier you can make that conflict, the juicier the story tends to be. And the writers here do such a good job creating the conflict between these two women. In the end, that’s all that was needed – two people going at each other and let’s see how this ends.

The third episode, Plaything, is the darkest of the four episodes I watched. It follows this strange older man who’s arrested by police under the suspicion that he’s responsible for a recently discovered suitcase that contains body parts in it.

The episode takes place mostly in an interrogation room at the police station and the two cops interrogating the man are baffled and frustrated when he tells them that all of this goes back to a video game he used to play 30 years ago – “The Throng.” The game consisted of the first digitally sentient beings in a game. These things understood their own existence. And they started replicating over the years, becoming a bigger and bigger civilization. As a result, he’d been tasked with growing the hardware over the decades so they could keep expanding.

But, finally, they’ve gotten too big for the hardware, which means there’s only one place left to expand – the internet. This, it turns out, was our older man’s plan all along. Get captured, come in here, and use a sleight-of-hand QR code trick to send the Throng into the UK’s governmental computer, via a nearby security cam. Soon, the Throng will be everywhere. And humanity will never be the same again.

If you know me, you know that I like when writers use common scenarios to build their scenes and stories around. I talk about this in my dialogue book. Common situations are your friend in writing. Interrogations, in particular, are fertile grounds to create interesting scenarios because the audience already understands the rules and these situations themselves are often high stakes, since murder is usually involved.

And you can see, with this episode, that as long as you inject that scenario with a fresh angle, you can still tell a fresh story. Interrogations very well may be 500 years old. But none of them have involved somebody talking about a video game that eventually becomes a threat to all of humanity. You take something old and you combine it with something new. That’s what makes it fresh (and that’s what’s made Black Mirror such a success).

The final episode I watched was the sequel to U.S.S. Callister. The U.S.S. Callister is considered by many to be the best episode of Black Mirror ever. It follows an evil coder, Robert Daly, at a game company, who digitally replicates his coworkers via a DNA-to-digital machine, which allows him to put their digital clones into his own version of the game, where he can then lord over them like a God.

In this sequel to the original, the New York Times has gotten wind of a rumor about the digital clones. If true, it would sink the company. So the president tasks one of his coders, a young woman named Nannette, to figure out what’s going on. When Nannette learns that her own digital clone, as well as five others, are in the game, she must figure out a way to save them. Meanwhile, the digital clones are in the game fighting off real players. The difference between them is, if the players die, they can just respawn. If a digital clone dies, they die for good.

For the most part, I enjoyed this sequel. However, it’s a reminder that the more complex the rules are, the harder it is for the average reader/viewer to keep up. I’d forgotten the rules from the original movie, and it took a good 45 minutes to remember how it all worked. Basically, it was hard to track the exact connection between the real world people and their digital clones. How much did they know about each other? How did they communicate?

I always tell writers to keep your sci-fi rule-set as simple as possible. Most writers enjoy getting into the weeds of their rules and, in the process, we, the reader, get left behind. This just happened recently. I read a sci-fi script with way too many rules and it, ultimately, took the screenplay down.

At the very least, if you have a lot of rules, you have to be awesome at explaining them to the reader in an understandable way. That’s where you see the biggest difference between pros and amateurs. Despite some of my issues with the excessive rule set here, I ended up understanding them by the end and, in most amateur scripts that tackle rules this extensive, that wouldn’t have happened.

Ultimately, I think the movie suffers from Cristin Miloti carrying the load. She’s great to look at but she is nowhere close to being able to carry a movie all on her own. She’s just not interesting enough as an actress. The reason that first movie was so good was 50% due to the writing and 50% due to Jesse Plemons. Without Plemons playing a major role here, the sequel doesn’t compare to the original.

But it’s still solid. What did you guys think?

I’ve been dropping in on the various post-White Lotus interviews to get more context on the season. I don’t like to do this at the beginning of a show because I feel like I might stumble across spoilers. But at the end of a show, especially one I love, I want to know everything I can about it.

So, I want you to think about your journey as a writer and why you’re doing this. I want you to imagine what it might look like if you’re super successful. If it’s anything like what *I* would imagine, I would say that Mike White is experiencing the pinnacle of what success looks like as a screenwriter.

He’s got the most talked about show in the world at a time when it’s harder than ever to stand out in television. Despite the massive success he’s found through the first two seasons of White Lotus, the third season is even bigger, becoming a bona fide phenomenon. The finale tallied a 30% increase over the second season’s finale. And the show has become a social media juggernaut, spawning more memes than a presidential election.

So I was surprised when I began listening to Mike White’s recent interviews and noticing that he didn’t sound happy. He seemed jostled by some of the show’s criticisms (that the plotting was too slow, that there were no police scenes after the giant shootout, that Lachlan would make a smoothie without cleaning the blender first), and he ended up telling Howard Stern he needed to “get away from all this for awhile.”

This both terrified and fascinated me. Here this screenwriter is, experiencing the pinnacle of what it’s like at his profession, and he’s not happy. If there’s anybody who should be ecstatic about a writing accomplishment, it should be Mike White. Yet here he is getting riled up about these criticisms people have with his mega-successful multiple-award-winning show.

The more I thought about this, the more I realized that screenwriters are an unhappy lot. They’re always complaining. They’re always frustrated. And they always think that the next hill they’re able to climb will solve their happiness problem.

They think, if I can just get an agent, I’ll be happy. But then they aren’t because they learn agents are not magicians. So they say, if I can just sell something, I’ll be happy. But then they aren’t because the money they receive only goes so far. So they say, if I can just get something produced, I’ll be happy. But then they aren’t because a lot of the show/movie gets rewritten and the product ends up subpar. So they say, if I can just make something that gets a lot of critical acclaim, I’ll be happy.

And that’s the one you’d think would be impossible not to be happy about. But guess what? Mike White shows that you can still be unhappy when you get to the top of the screenwriting mountain! Because when you make something critically acclaimed, you face a new obstacle – expectations. And you’re never going to be able to make everyone happy. So if your goal is to have every single person love your show, you will never ever ever be satisfied.

Why do I bring this up?

Because artists are, sadly, predisposed to being miserable. Especially writers. And if we’re never going to celebrate our wins, what’s the point of doing this? If you’re going to be just as frustrated with a giant hit show as you are “only” getting to the second round of the Nicholl Screenwriting Contest, then why even bother?

The truth about screenwriting is that there is no such thing as a perfect script. Because in order to write a great script, you must sometimes do the “wrong” thing. You must sometimes write an unlikable protagonist. You must sometimes write on-the-nose dialogue. You must sometimes have a character do something that a real person wouldn’t do in real life, like make a smoothie without cleaning out the blender first. And all of these things are technically going to make your script “imperfect” but that’s what makes the script great! It’s that splash of imperfection.

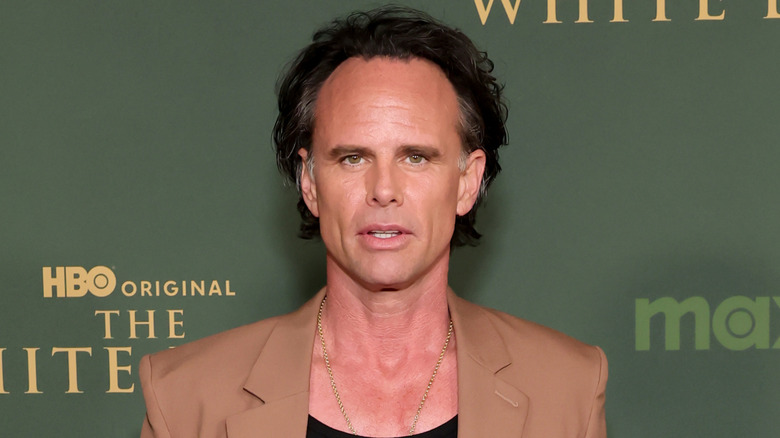

Scripts are like people. The most interesting ones have flaws. If a script is “perfect,” it’s like looking at someone who’s had 15 cosmetic procedures on their face. Sure, their face is “perfect,” but that person is never going to be as interesting to look at as, say, Adrian Brody, with his big nose, or Amie Lou Wood, with her funny teeth, or Walton Goggins, with his adventurous hairline.

You don’t want to purposefully aim for your scripts to be imperfect but you want to follow your heart when you write and trust yourself that it’ll be okay. As long as those imperfections are contributing positively to the overall story, you’re good.

One of the criticisms that Mike White seems to have taken offense to the most is his handling of the shootout and the way the bodyguards acted (they originally chased after Rick then easily gave up). Was it perfectly done? No. But you know what? I thought nothing of it at the time. I only found out afterwards that people had issues with it.

White actually talks about it. He says he doesn’t do gunfights in his films. His films are always character-driven. So it was not something that he was very good at.

You wanna know why I thought nothing of it at the time? Because I was invested in the characters. That’s what Mike White knows that not enough writers know – if you get the characters right, the majority of viewers/readers will not care about your errors. 1) Create interesting characters with flaws that arc over the course of the story. 2) Create interesting relationships with the other characters that contain conflict that needs to be resolved. If you do those two things, 99% of people won’t care that the shootout was sloppy. From everything I saw on social media, the parts of that scene that fans focused on most were the tragic death of Chelsea and how Laurie comically sprinted away from the shootout like a bat out of hell. They focused on the character stuff.

Look, if people are talking bad about your script? If people are talking bad about your show? THAT’S GREAT. That’s all that matters. Because the worst thing that can happen when you release a show or movie is not that you get some criticism. It’s that NOBODY CARES. Nobody talks about your show at all. Did anybody here know they made a TV adaptation of the movie, Cruel Intentions? Yeah, they had a full season of it. Did you know that? No. Nobody does. Because nobody talks about that show.

THAT’S the worst thing that can happen. If people are complaining about your show, it means they care!

I guess I’m sad that Mike White is sad. This should be the happiest time of his life. And I feel like so many people in this business are like him. I just met this fitness influencer who recently gained a ton of followers on social media and she was telling me how upset she was about various issues that had come up with her success (more haters being the main one). And I’m thinking to myself, “You’ve got one million followers. If you can’t be happy about that, when are you going to be happy?”

Guys, writing is supposed to be fun. That’s why we got into it. If you’re unhappy, you’re probably focusing on the wrong things. Instead, shift your focus to the fun of telling a story – of coming up with a great character, or setting up the perfect payoff, or coming up with that amazing plot twist, or writing a great scene. And be kind to yourself. Celebrate the wins.

When your script is done, put it out there, hope for the best. But don’t tie your happiness to whether people like your script or not. You just can’t predict how people will react. If people love it, great. Ride that wave as long as you can ride it. But if they seem indifferent, you’re a writer. Come up with a new idea and write THAT. That’s what you do.

The quickest way to give up in writing is to become bitter and angry about it. Don’t do that! Write stories because you love to write stories and that way you’ll be happy at every stage of your success.

Genre: Drama/Sci-Fi

Premise: A woman begins dating a perfect handsome man only to discover that he may not be human.

About: Today’s screenwriter, Kate Folk, authored the short story collection, Out There, which today’s script is based on. She has written for publications including The New Yorker and the New York Times Magazine. She was also a Wallace Stegner Fellow in fiction at Stanford University. The script appeared on last year’s Black List.

Writer: Kate Folk

Details: 111 pages

Pattinson for Roger?

Pattinson for Roger?

It’s appropriate that Black Mirror comes out with a new episode this Friday because today’s script is less a feature film than it is a storyline for a Black Mirror episode. Let’s see if it’s any good.

Normal-looking Alicia and newish drop-dead gorgeous boyfriend, Alan, have just spent an amazing night in a cabin in Big Sur, a picturesque resort town on the northern coast of California. While Alicia sleeps, Alan gets up, props open Alicia’s laptop, and his eyes go milky. Seconds later, the laptop dies. He does the same with her phone. He then walks over to the window, dissolves into a ball of energy, then dissipates.

Cut to a week later where we meet San Francisco eye-surgery tech, Meg, who is still hurting after getting dumped by her boyfriend, Matt. Although Matt was, by no means, perfect, he’s a lot better than all the losers she’s been dating on these dating apps. She not-so-secretly yearns to jumpstart their relationship again.

And she gets her chance when she arrives home one night and Matt is at her apartment, talking to her passive-aggressive roommate, Genevieve. Matt is happy to see Meg and asks her if she wants to be his ‘plus-one’ at a work dinner event. She doesn’t have to think twice.

When she shows up at the dinner, Meg is upset to learn that she won’t be sitting with Matt but, rather, a group of random people at a table. She’s ready to explode until she meets the guy she’s sitting next to – the gorgeous perfect gentleman, Roger. Roger is instantly smitten with Meg, which throws her off. Guys this handsome don’t usually pay her attention.

Soon the two are texting each other, talking all the time, going on dates. But it doesn’t escape Megan that Roger is kind of… odd. He’s overtly formal in the way he speaks. He’s way too polite. He seems to have zero concept of how handsome he is. And he quadruple texts! Everybody knows, on the dating scene, that it’s suicide to even DOUBLE TEXT. So clearly something’s not right.

Soon, Roger is pushing Meg to go with him to Big Sur. Everything is “Big Sur, Big Sur, Big Sur.” He’s pushy enough that Meg is cautious. And that’s when the story breaks. Alicia, the woman from the opening, reveals her story to the news – which is that some shady Russian tech company has created AI men who are designed to lure in unsuspecting average women, take them to Big Sur, then steal their entire digital lives (identity, bank account, job, etc).

At first, Meg is mortified. But when these men – known as ‘blots’ – start getting arrested across town, Meg feels bad for Roger, and continues to see him, even providing him safety from the authorities. When it becomes clear that Roger’s programming is geared towards climaxing at Big Sur, Meg decides to go with him, understanding the consequences. She prepares all of her data for its inevitable theft, but has she prepared for everything?

I used to think that “voice” was all about the way your characters spoke—that the offbeat sense of humor you gave them made up 90% of your voice as a writer. Think John Hughes, Diablo Cody, or Quentin Tarantino.

But I’m starting to realize that it’s more complicated than that. Voice begins with the type of subject matter you choose to encase your story in. For example, if you’re into car chases and shootouts and you write your scripts accordingly, those are pretty broad topics. They appear in a lot of movies. So someone who writes about them won’t be seen as a “unique voice.”

Meanwhile, if you write about professional apologizers (these are real people in Japan), that subject matter is much more niche and allows your story to stand out amongst others. It is the starting point for creating a unique voice.

Also, any movement into fantasy/sci-fi is an opportunity to isolate your voice from others. Here, Folk has created these entirely AI human beings that disappear into balls of energy once their mission is accomplished. Again, that’s a very niche idea and, therefore, helps form a specialized voice.

Once you mix in how you see the world, your voice as a writer really starts to stand out. Maybe you see humanity through the lens that people are inherently good and eager to help one another. Or maybe you see it as everyone being selfish, always looking for an angle or a way to take advantage. Either perspective can shape your storytelling.

You can also dive into the nitty-gritty—like how your characters approach dating. The way someone sees the dating world has a huge impact on how their story feels. Are they hopeful? Hopeless? Do their characters take whatever they can get, or do they never settle? Whatever angle you choose to highlight usually reflects how you see dating, and that perspective becomes a key part of your voice.

To summarize, if you can mix a series of offbeat viewpoints together, you can really stand out as someone with a unique voice. Which is why I think Kate Folk is one of the better writers on last year’s Black List. Because while her story itself isn’t very sexy – it’s basically about a relationship – all of these unique ways in which she sees things give the script an unusual tenor. It’s covering a basic human relationship yet it doesn’t feel like something we’ve read before.

Now, I didn’t say that meant it was good. There isn’t enough plot here. But there’s enough to keep us engaged. I thought one of the more interesting creative choices Folk made was to expose Roger at the midpoint. Most writers would’ve kept the dramatic irony going – where we knew Roger was bad but Meg didn’t – all the way to the Big Sur climax.

But, instead, Folk uses that plot development (blots are exposed) to alter the story. Now it becomes a riff on Steven Spielberg’s “A.I.,” where Meg is harboring Roger and decides she wants to help him complete his purpose. While I wished there would’ve been higher stakes for Meg, the stakes are still high enough on Roger’s end (he’s going to die) that the climax had weight.

If you’re looking for how to write a script that hits people viscerally, like yesterday’s Bato Bato, this script is not for you. But if you’re trying to find ways to better express your unique sensibilities through your screenplays, you’re going to want to check this out.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: Here’s Kate Folk on how to approach writing first drafts – “I find first drafts challenging and, actually, I prefer the revision stage, because it seems so daunting to create something out of nothing. My strategy for that is to pour as much content on the page as I can, so that then I have something to work with and transform from there.” I agree. When you’re struggling to get your script out, drop the judgment and just put words down on the page until you finish. It won’t be perfect but at least you’ll now have clay that you can start molding.

Maybe the most unique screenplay of the year!

Genre: Thriller

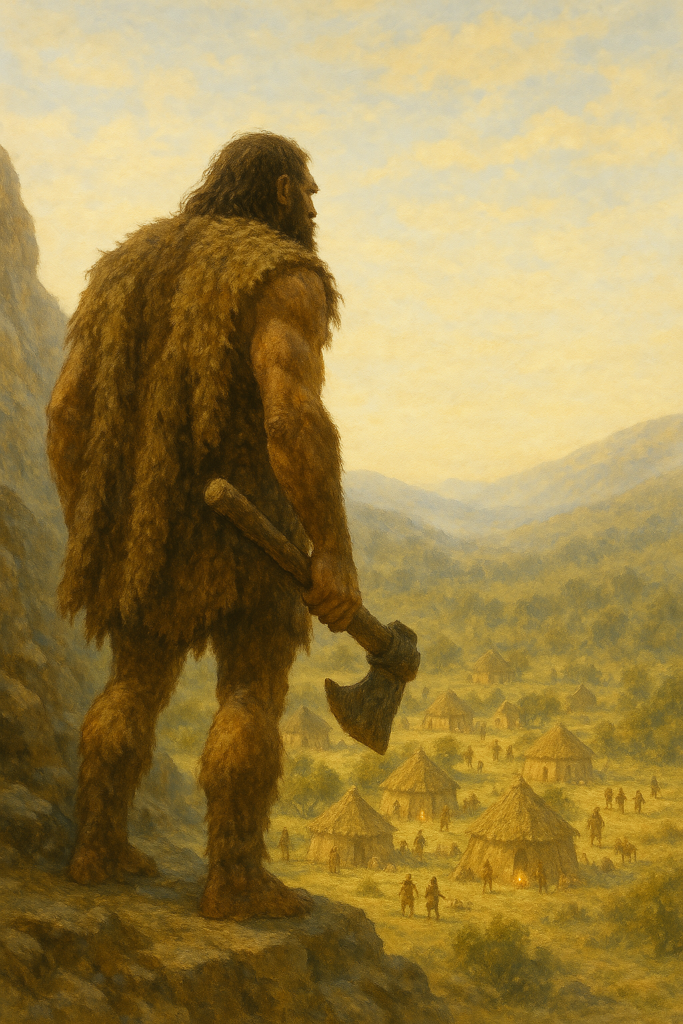

Premise: When his family is murdered and his child kidnapped, a Neanderthal goes on an epic rampage journey to save her from the new dominant species, homo sapiens.

About: This script made last year’s Black List. Donn Kennedy is a writer out of Milwaukee Wisconsin who has been writing for nearly 20 years.

Writer: Donn Kennedy

Details: 96 pages

I don’t think I’ve ever read a script where the writer has loved their script as much as this one. Donn Kennedy is having so much fun writing this that, at certain points, I thought he was experiencing some nirvana-like ascension to another plane.

Generally speaking, if the writer is having fun, the reader will have fun, too. However, you can overdo it. By only focusing on your own enjoyment, you can lose touch with the reader. So, which happened here? Let’s find out .

It’s 40,000 years ago.

It’s a time when you either kill or be killed. Society hasn’t really started yet. So, mostly, you’ve got these individual Neanderthal families scattered about, trying to get by. Our protagonist Neanderthal family is made up of the father, Bato, the mother, Kaza, and twin 13 year olds, Meeka (a girl) and Booka (a boy).

Bato is definitely a badass. He’s got a mysterious scar slashed across his face. The dude heads out every few days and kills a mammoth so his family can eat. His son, Booka, is a burgeoning artist, writing up stories on their cave wall. His daughter plays the bone flute and is pretty good at it. It’s your typical Suburban Neanderthal family from 40,000 years ago.

But, one day, when Bato is out hunting, a group of people come to his cave and murder his family. Well, they murder Kaza and Booka. Meeka was able to fight back and kill one. But the others still kidnapped her. When Bato arrives post-slaughter, he removes the mask of the bad guy to see… A SHOCKING FACE. Smaller nose. More distinct features. A homo sapien!

Bato immediately grabs his things and goes to find his daughter. But you have to remember, this isn’t some waltz through the local forest preserve. This is a land of endless predators. Bato finds that out immediately when he catches up to the group crossing a river in some kind of contraption (a boat).

Bato takes on Yama and kills him, then uses an alligator carcass to swim across the river and not get attacked by other alligators (it doesn’t work – the alligators attack him). Not long after that, he falls into a literal Venus flytrap. Like, one big enough to hold a Neanderthal. He uses fire to smoke his way out of that.

He eventually runs into a tribe of people who provide some much-needed first aid, only to then tie him up and march him out to some pole. Turns out they’re cannibals and they’re going to eat him! He cuts the rope and takes out 20 cannibals in a chaotic running dance through a bunch of hot-spewing geysers.

But the further he travels, the more distance the homo sapiens seem to create. Soon, he’s lost, turned around, and after two long years of pursuing his daughter, he’s shocked to find that he’s done a giant circle and ended up right back at his cave house. Hey, GPS was still in its infancy 40k years ago. Give him a break.

When Bato discovers another group of homo sapiens nearby, he fights them off. But when he’s about to kill one, he pulls off her mask and discovers that it’s… HIS DAUGHTER! But they don’t have time to reunite because Kaza, the leader who kidnapped her two years ago, is closing in. They must split up and Bato loses his daughter AGAIN! But he eventually discvoers where the homo sapien village is. So he arms himself and goes in for the final battle!

One of the things I crave most as a reader is SOMETHING NEW. I want to experience something I haven’t experienced before. The more unique moments you can pack into your screenplay, the better.

This script achieves that. It’s not like any script I’ve read in a long time. Bato is always running into something shocking – shocking for him, shocking for me. For example, he falls into this cavernous valley at one point and the next thing he knows, he’s face to face with a Homo Habilis. Just like the Homo sapiens wiped out the Neanderthals, the Neanderthals wiped out the Home Habilis.

Except there are a few still around. And this one is 7 feet tall and has the anger of his entire race ready to throw at Bato. It’s moments like that that made this script stand out.

Another thing that Kennedy did well is he made the writing sparse. Most paragraphs are one line long. He uses a lot of GIANT FONTS to emphasize the intensity of the moment. And what this does is it makes sure our eyes fly down the page.

Why is this important? Because there’s no dialogue. And I have seen many a non-dialogue screenplay die a quick death because they take forever to read through. Remember, dialogue takes 1/4 the time to read as a description. So readers love dialogue. Cause it allows them to shoot through a lot pages quickly. When you take all that dialogue out, a 100 page script can read like a 300 page script.

So it’s good that Kennedy understood that and created a writing approach that still allowed the script to read fast.

On the flip side, the writing here is borderline annoying. Every line is so on-the-nose that it’s hard not to roll your eyes at times.

And if you’re a reader who doesn’t like when the writer talks dirctly to you? You’re not going to like this script. Kennedy loves to tell you how he just made cutting the trailer easier, how much you’re going to love a scene cause it’s just like “Oldboy,” he even celebrates, on the page, pulling off successful setups and payoffs. There’s a ton of that here.

When it comes to flashy writing like this, I’m not going to say don’t do it because, the truth is, people either love it or hate it. And maybe it’s worth losing the haters if you gain the lovers in the process. The opposite of this is an entirely neutral style and that can be so boring that nobody likes it. So it’s a creative choice. Just know that you’re going to piss some readers off and they’re going to let you know about it.

As for the story, I thought the worst choice was the cut to two years later. I hate any big time cuts in a story because they tank all the tension you’ve built up. I mean, imagine if, at the beginning of last night’s White Lotus episode, there was a title card that said, “3 weeks later.” And the whole episode took place at the island 3 weeks later. Everybody watching would be like, what the f&%$?

I know why the writer did it. He did it to create the moment where Bato unknowingly fights Meeka. He did this because he’s a giant fan of Oldboy. I only know this because he says so earlier in the script. So, the big twist in that movie obviously motivated this plot development here, and this is something I always warn writers about. You want to be inspired by your favorite movies. But you don’t want them to impede upon your scripts too much.

There’s a huge reason why that twist was needed in Oldboy. There was no reason to cut to 2 years later here. The script would’ve been better had we kept the tension throughout, never leaving this timeline. The only reason that mistake was made was that the writer was obsessed with another movie. Make creative choices only to create the best version of YOUR MOVIE.

Overall, I don’t know how to rate this script. It’s got some great stuff. It’s got some terrible stuff. I do think the pitch of “Taken 40,000 years ago” is a good one. And the script is very visual. You can see, with a good director, this looking like a really cool movie.

So, for that reason, I think it’s ‘worth the read.’ And let me be clear about that so you understand. As a script, I would probably give this a “wasn’t for me.” But when you take into account how unique the concept is combined with how visual the movie would be, that’s what makes it read-worthy because the endgame here isn’t putting words on a page. It’s getting movies made. We should all be writing scripts that, like this one, have a shot at becoming a movie.

[ ] What the hell did I just read?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[x] worth the read

[ ] impressive

[ ] genius

What I learned: You have to give the reader room to interpret what you’ve written. If you don’t, you risk being on the nose. Here’s a segment of the scene after Bato finds his family.

She’s alive! But mortally wounded

Falls by her, Bato cradles her head

His love. His world. The only thing good in this god forsaken prison of existence.

There is no reason for this third paragraph. None at all. You have to trust that the reader understands the gravity of this moment. You don’t have to yell it in his ear.

What I learned 2: This is the stuff that AI is great at. If you have a story idea like this, feed it into your favorite AI client and ask it, “What are 50 unique things my character might encounter on this journey, stuff that the average person woud never think of today?” And it will. It will give you at least 25 things you hadn’t thought of. And you can then build a lot of your plot beats or set pieces around the best of those things.

I was just going to make this a White Lotus post but I can’t ignore a record-setting weekend at the box office when we don’t get many of those anymore. Minecraft made 160 million dollars over the weekend, making it the biggest video game adaptation opening ever. That’s impressive.

So why did it happen? Here’s my theory. For the longest time, video game adaptations, like Doom and Assassin’s Creed, were competing for time from an audience who, historically, prioritized MOVIES over VIDEO GAMES. So, they always liked movies that were MOVIES.

But Minecraft is coming out at a time when the first generation that grew up priortizing VIDEO GAMES over MOVIES is now going to the movies. You can see that in the audience makeup. These are all kids at the showings. Kids who would rather play Minecraft than watch Star Wars. That generation is going to be a lot more open to video game adaptations.

So, I think what you’re going to see is a lot more video game adaptations and they’re going to do a lot better than video game adaptations of the past. Movies, meanwhile, are going to have to figure out how to compete with this. The simple answer is write better scripts and make better movies. But people don’t have a lot of confidence in that formula these days.

By the way, random fact I found out. The Minecraft movie was put together by the old Napolean Dynamite team. These guys actually have a unique voice. They’re not your average studio directing team. That probably had a big influence on the movie’s success as well.

Okay, onto the big show.

What we’ve all been waiting for.

The 90-minute White Lotus finale. Was it everything I was hoping for and a thousand things more?

Cause this show really rallied in the Scriptshadow household. After that silly snake-show episode, I was worried big time about the season. But it built its story back brick by brick and clawed its way up to the quality of the first two seasons.

Still, it needed to land the plane.

Did it?

Let’s just say this. Word was that the finale was bonkers. That was 100% verified tonight. IT. WAS. BONKERS.

****SPOILERRRRSSSSS****

There were some whopper climaxes here, none whoppier than what will forever be known as the White Lotus Empire Strikes Back moment. We’ll get back to that.

But let’s start with how Mike White subverted his climaxes. He gave you what you thought were climaxes. Then, right when you were about to wrap your arms around them, he pulled them back and gave you the real climax.

There was the secret family suicide pact that only Father Ratfliff knew about. White made us think that the whole family was going down. Then, at the last second, the dad changed his mind. The family was spared. Or so we thought. We are then horrified to see Lochlan fix a smoothie the next day, realizing that he’s going to ingest the last of the poison and die.

Another great climax subversion occurs with Rick Hatchett. We thought we finally got the conclusion to his life-long search for his father’s murderer last episode, only to learn, this episode, from resort owner Jim Hollinger, that the angelic portrait that Rick’s mom painted of his father was a complete lie and that his father was a terrible person. This reignites Rick’s desire to kill Jim, and a second storyline climax is on.

The reason these climaxes were so impressive is because the majority of screenwriters give you the climax you expect. There are tiny surprises along the way but we pretty much know what’s going to happen. Mike White faking a pass to us before he goes in for the dunk is what separates him from everyone else.

I can’t emphasize enough that Mike White does not have anything to work with here besides characters. He doesn’t have superheroes. He doesn’t have superpowers. He doesn’t have magic, or giant lizards, or the Force, or time-travel, or any of the things that other writers have access to to mesmerize audiences.

He just has characters and he’s so good at utilizing those characters in dramatic ways that nearly every scenario he creates is compelling.

If Mike White did have a superpower, I’d say it was setups and payoffs. I mean who would’ve thought that Saxon annoyingly ordering a blender from Amazon in the first episode so that he could meet his protein quota on vacation, would turn out to have such a giant influence on the finale? That’s what good setting up and paying off does.

And hey, did anyone read that article I posted on Friday? The one about how much bang for your buck you can get using ANTICIPATION as a screenwriting tool? I think Mike White might have. Cause the first half of this episode was driven by a succelent anticipation narrative – that the dad was planning to kill his family.

Once we see Timothy learn about the poisonous fruit growing nearby and we see him put two and two together with that blender, we know it’s going to be lights out for this family soon. And the great thing about this particular use of anticipation is that when you make it this powerful – as I said in the article, ramp up the stakes as much as you can for maximum impact – it not only drives THAT storyline, it drives the surrounding storylines as well.

Every time we cut to a different set of characters, we have this excitement/dread brewing in the back of our minds regarding what’s going to happen to the Ratliff family.

But there’s one scene that really represents Mike White’s talents as a screenwriter. And it’s not the best scene in the episode. It’s not even in the top 8 scenes. But it shows that you can do some powerful things with just three people and dialogue.

The scene occurs early in the episode, when Daddy Ratliff (Timothy), Mommy Ratliff (Victoria), and their daughter, Piper, are having breakfast after Piper has spent a “test” night at the monastery she’s hoping her parents will let her attend next year.

In fact, this is the whole reason the Ratliffs are here in Thailand. Piper tricked them, saying she was going to do an interview with the head monk, then revealed her bait and switch once they were there – She wants to live here for a whole year next year.

When Victoria learns this, she is mortified. Victoria is the typical Beverly Hills trophy wife who has grown dependent on the finer things. To think of her daughter stuck in this bare-bones smelly sweatshop of a monastery for a year is her worst nightmare. She wants Piper going to college, then going to grad school, then marrying a rich man, and living the same life she lives.

So Victoria allowed Piper to spend one night at the monastery hoping it would rattle her and make her want to stay in the U.S. So Piper spends the night there. It is indeed dirty and sparse and the food sucks and there’s no air-conditioning. And the scene in question happens the next morning at breakfast between Piper, Timothy and Victoria.

In the scene, Piper breaks down in tears, coming to terms with the fact that she is dependent on the finer things in life. That she isn’t capable of slumming it. And she hates herself for it but it’s also something she realizes is her truth.

Meanwhile, Victoria is absolutely ecstatic. It takes everything within her power not to stand up and start dancing. She’s so happy that her daughter is seeing the light.

Cut over to Timothy and he’s going through a completely different experience. By hearing that, like his wife, his daughter cannot live a life without the finer things, that means that he’s going to have to kill her in his suicide plan as well.

For those who haven’t watched the show, Timothy learned at the beginning of the vacation that his entire empire back in the U.S. is crumbling and that when he gets back, he’ll be sent to prison and lose every penny he has. Knowing that his family members cannot live that life, he is sparing them by taking them with him when he kills himself.

The power of this scene is that three characters are having three very different experiences despite all of them being at the same table discussing the same thing. One is crushed that she’s not who she thought she was. Another is ecstatic that her daughter isn’t going to ruin her life. And the third is devastated to learn that he now must include killing his daughter along with his wife and son.

Most of the three-person dialogue scenes I read in scripts are on-the-nose. There is no depth to the conversation. Characters are not experiencing different things. It’s all very straight-forward.

But here, White stragetically uses setups within his storylines so that he can create these rich multi-layered dialogue scenes.

So, I’m sure you’re all wondering, “What do I think about the “He is your father” moment? I think Mike White went too far. He obviously knew that if Scot Glen said the line (“I am your father”) he’d be crucified, so he wisely moved the line over to the wife. But I’m just not sure it works.

The success of these revelations depends on the audience having a certain amount of information. We had the perfect amount of information and not a line more for Darth Vader’s revelation in The Empire Strikes Back. But here, I feel like we were a good paragraph or two short of the amount of information we needed for this reveal to work. I just didn’t know enough about Rick’s father to care that this other guy ended up being his father.

This is actually one of the downsides of having such a successful show. You can’t test moments like this out like you could before. And I suspect that White wanting to keep this moment a surprise prevented him from seeking feedback and being able to gorge the reveal with the fuel it needed to shine.

But it didn’t bother me. The episode was jam-packed with excitement. It was never boring. If I had to rank them, I would say that this is the best final episode of the series. Season 1 was incredibly strong. But the sheer magnitude of everything going on here gave it the edge.

Another giant win for Mike White. This show has become my Super Bowl of Screenwriting Celebration and, therefore, I’m really depressed that it’s over. Is it confirmed that he’s making a Season 4? I know it’s assumed. But is it CONFIRMED?? Do we have linked quotes somewhere of Mike White saying, “Yes, I’m doing a 4th season?” God, I hope so. A world without The White Lotus is a much emptier world!

[ ] What the hell did I just watch?

[ ] wasn’t for me

[ ] worth the stream

[xx] impressive

[ ] genius